Finance and Public Administration Committee

Pre-Budget Scrutiny 2022-23: Scotland's Public Finances in 2022-23 and the Impact of COVID-19

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on every aspect of our lives; our health, our jobs, our businesses, and the way we work. Each of these areas has required public investment on an unprecedented scale and speed and the impact of the pandemic will be felt for years to come. As we look ahead to recovery, the Committee has focused its pre-budget scrutiny 2022-23 on the impact of Covid-19 on Scotland’s public finances. We were also keen to find out how the fiscal framework, which underpins the Scottish Budget process, has held up against the challenges of the pandemic, ahead of a review of this framework in the coming months.

The Committee received 46 responses12to our call for views between late June and mid-August 2021 and we heard evidence from four panels of witnesses over two meetings in September.3 We also held additional sessions to inform our pre-budget scrutiny, hearing from the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) and Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy on the SFC’s August Economic and Fiscal Forecasts4 and from the Auditor General for Scotland on Audit Scotland’s ‘Tracking the implications of Covid-19 on Scotland’s public finances’ report.5 Our final evidence session with the Cabinet Secretary on 5 October also covered the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework Outturn Report6 published on 30 September. The Committee thanks all those who contributed their views, which have shaped this report, as well as our adviser, Mairi Spowage, for her invaluable expertise throughout this inquiry.

The UK Government’s Autumn Budget (2022-23) and Spending Review 20217 and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) Economic and Fiscal Outlook8 were published on 27 October, after we had concluded our pre-budget evidence-taking. Given the time available we have therefore reflected the key aspects of the OBR’s economic outlook and findings in this report.

Economic and Fiscal Outlook

UK economy

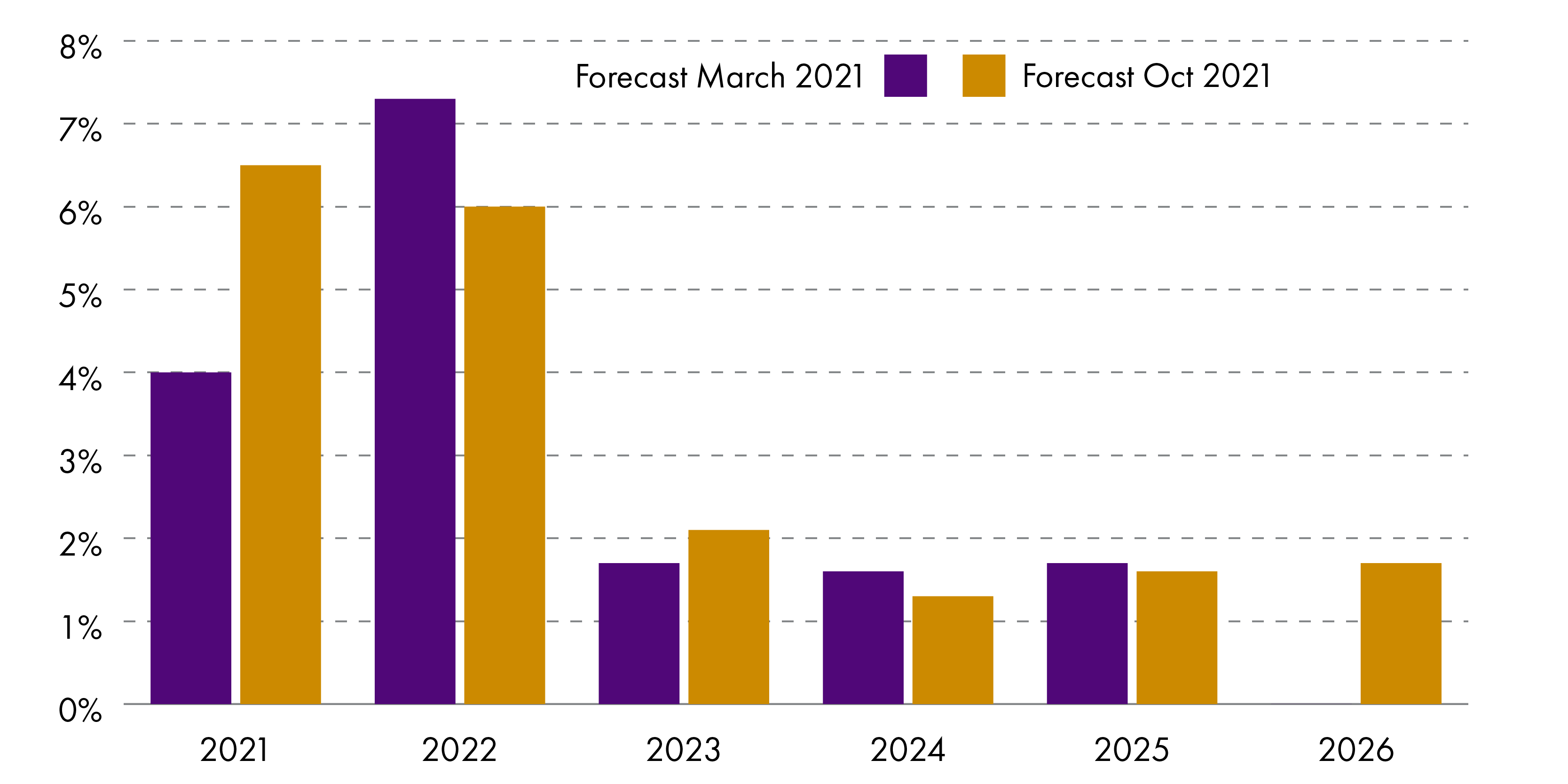

The OBR’s latest forecasts for the UK economy, published on 27 October, are its first forecasts since early March 2021.

Following stronger than expected growth in the first half of 2021, supported by the vaccine roll-out during that period, the OBR has, like most forecasters, revised up its expectations for growth over the next five years (see Figure 1). In particular, it has revised up growth for 2021, bringing forward some of the growth it was expecting in early 2022. Overall, over 2021 and 2022 combined, the OBR considers that the economy will grow more quickly than expected in March 2021, then moving back to more ‘normal’ levels of growth.

The OBR’s expectation is that the UK will now reach pre-pandemic levels at the turn of the year, surpassing the levels in February 2020 by January 2022. Its view of the long-term scarring impact of the pandemic has also eased: it now expects the economy to be around 2% smaller in the long-run, down from the 3% set out in its previous forecasts.

The OBR now forecasts unemployment to peak at 5.25%, 1.25 percentage points lower than it forecasted in March, which is equivalent to nearly half a million fewer people looking for work.

It also highlights that Consumer Price Indexi inflation “has risen sharply in recent months, as the rebound in demand here and abroad has run up against supply constraints”. It reached 3.1% in September of this year, up from a low of 0.3% in November 2020.1

In its October 2021 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the OBR explained that inflation is expected to rise due to supply issues, migration and trading regimes following Brexit, soaring energy prices, labour shortages in some occupations, and blockages in some supply chains. The Committee notes that inflation rises can also be driven by inflation expectations, and there is a risk that, if companies, workers and consumers expect higher inflation, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The OBR expects “CPI inflation to reach 4.4 per cent next year, with the risks around that tilted to the upside”.2

However, the OBR has flagged that “inflationary risks have intensified” since it closed its forecast (in mid-October), which has led it to produce a number of scenarios, if, as it fears, its forecast turns out to be too optimistic. It adds that “our forecast would be consistent with inflation peaking at close to 5 per cent next year … and it could hit the highest rate seen in the UK for three decades”. The OBR considers that inflation will return towards the Bank of England’s 2% target by 2024. It also discusses the possible response from the Bank of England to increased inflation, such as inducing significant rises in interest rates, and the impacts on wages, the potential size of the economy, and the fiscal position.

UK fiscal outlook

Alongside the budget, the Chancellor proposed an update to the fiscal rules that he will follow, which still have to be debated and voted on by the UK Parliament, and may have an impact on the Scottish Budget.

More optimistic forecasts by the OBR, the tax rises that were proposed in the previous budget in March and the increases in National Insurance contributions (to be replaced by the Health and Social Care Levy), gave the Chancellor greater flexibility in setting his budget.

The October UK Government Budget was accompanied by the first UK multi-year Spending Review (SR21) since 2015, which set out UK Government departmental budgets up to 2024-25. According to the OBR, public spending is likely to be at the highest sustained level since the 1970s, with increases in spending across the UK, compared to previous plans of around £70 billion over the next five years. Taxes as a share of GDP continue to rise over the forecast horizon, due to tax policies like the National Insurance rise (to be replaced with the Health and Social Care levy) and other tax threshold freezes which bring more people and transactions into tax.

As a result of the Spending Review, the UK Government published its Statement of Funding Policy1 where it sets the policies and procedures which underpin the UK Government’s funding of the devolved governments, outlines the elements of that funding, and explains the interactions with the funding the devolved administrations raise themselves.

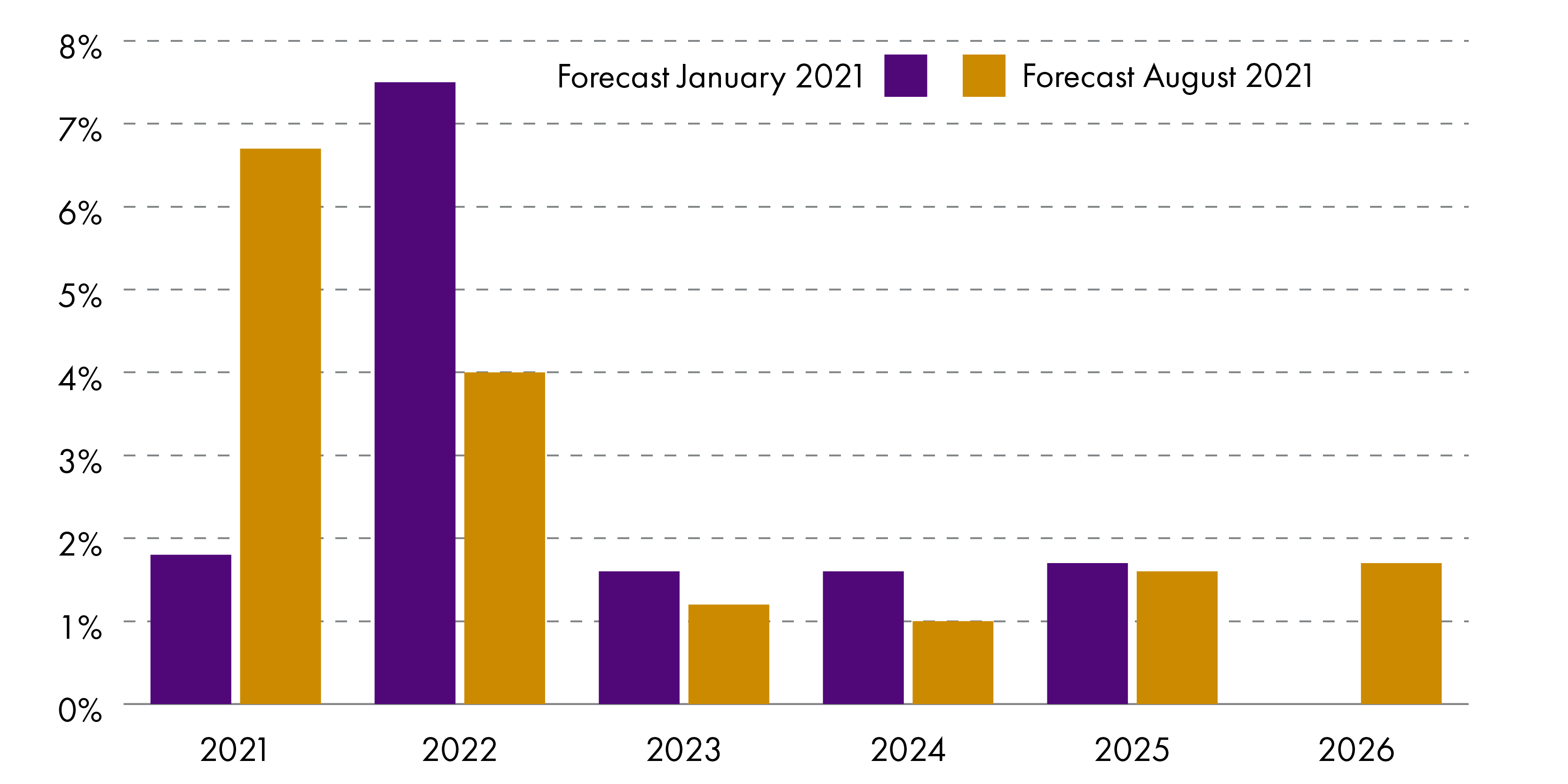

Scotland economy

The latest forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) were published on 23 August 2021. There was a significant improvement in Scotland’s economic outlook since its previous forecasts in January 2021 (see Figure 2), showing a similar increased optimism to that of the OBR in its latest forecasts. The SFC expects growth of 6.7% in 2021, with economic output reaching its pre-pandemic levels by 2022 Q2, around two years sooner than had been forecasted by the SFC at the start of the year.

The improvements to the economic outlook in August added almost £900 million to income tax forecasts for 2021-22 compared to the SFC’s January forecast. Under the fiscal framework, the net position between the SFC forecasts to be published alongside the Scottish Budget on 9 December 2021, and the forecasts produced last week by the OBR, are important to determining the size of future reconciliations.

Scotland fiscal outlook

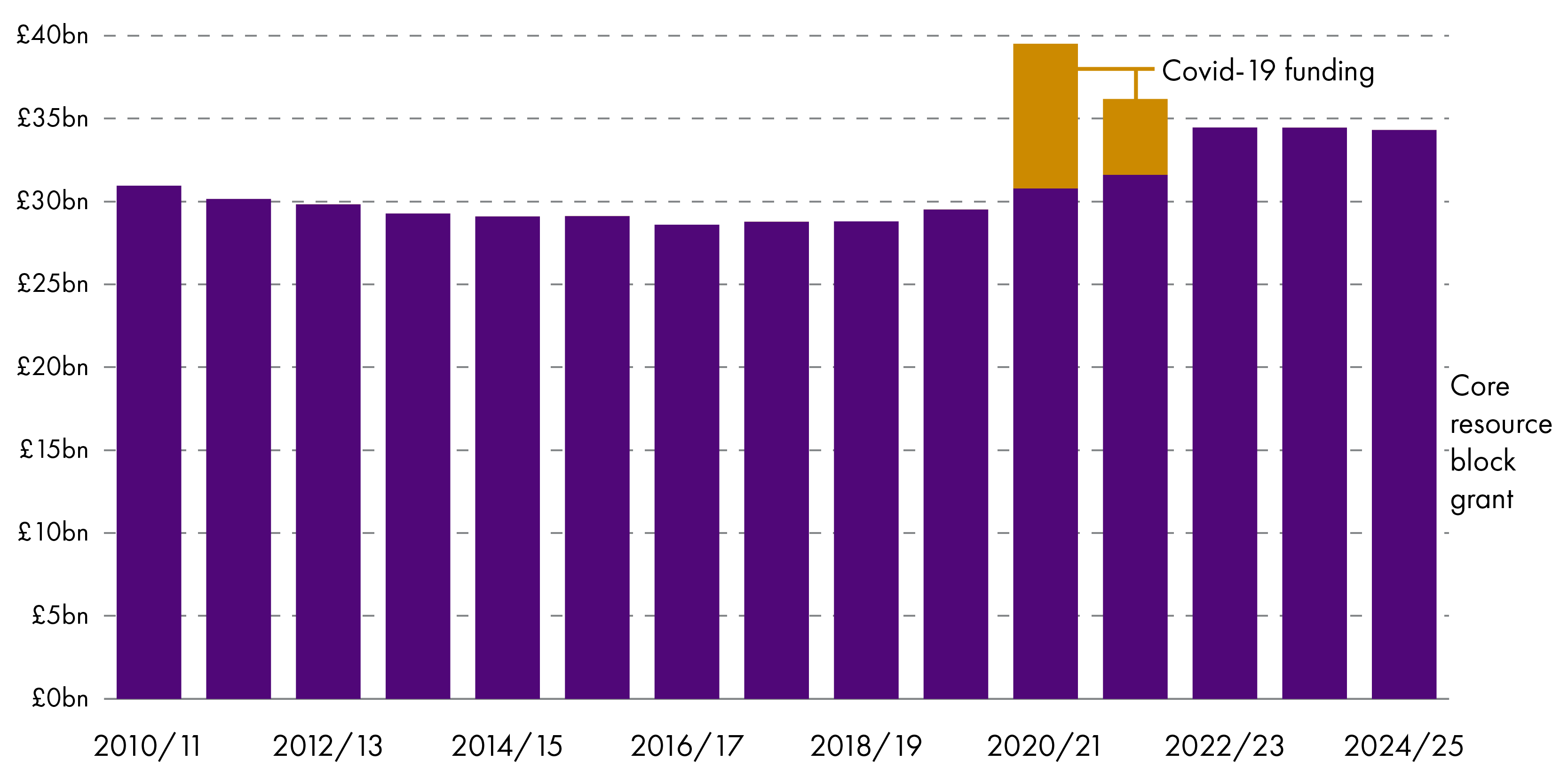

The UK Government’s October Budget improves the outlook for the Scottish Government’s resource block grant in each of the next three years, compared to what had been previously anticipated. The total DEL numbers are set out in Figure 3 below, along with the emergency Covid-19 spending that was provided through additional consequentials.i

| £ billion | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish total DEL | 32.9 | 35.5 | 36.7 | 40.6 | 41.2 | 41.8 |

| Covid-19 Consequentials | - | 8.6 | 4.7 | - | - | - |

There are two main reasons for this improvement. Firstly, UK Government departmental budgets have been increased, relative to previous plans set out by the UK Government which, when spent, will create increased consequentials for the Scottish Budget.1 Secondly, additional consequentials also flow to the Scottish Budget as a result of cuts made to business rates in England. Business rates revenue in England counts as a negative consequential in the Barnett formula, so a cut in English revenues of around £7 billion generates positive consequentials for the Scottish Budget.ii

Taken together these impacts create a large increase in 2022-23, with a relatively flat increase in real terms in the subsequent two years of the Spending Review period. Figure 4 below shows the Resource Budget (i.e. for day-to-day expenditure and excluding capital) in real terms from 2010-11, separating out the Covid-related spending in 2020-21 and 2021-22.

Use of borrowing and the Scotland Reserve

The Fiscal Framework Outturn Report (FFOR), published on 30 September, outlines the Scottish Government’s plans to use its borrowing powers and the Scotland Reserve.

For capital borrowing, under current plans, the Scottish Government will have accumulated just under £2.5 billion by the end of 2022-23, 82% of its overall £3 billion limit. In 2022-23 repayments for capital borrowing will total just under £115 million. Borrowing plans from 2023-24 onwards have not yet been announced. In general, capital borrowing tends to work out lower than planned, due to general slippage that can occur with capital budgets.

Resource borrowing can only be used for cash management and forecast errors. The Scottish Government’s FFOR states that £207 million was borrowed to cover the negative reconciliations and forecast error applied to 2020-21, and that the Scottish Government plans to borrow £319 million to offset the negative reconciliation and forecast error adjustment applied to the 2021-22 Budget.i It notes that “this borrowing has not yet been drawn down, as borrowing drawdowns are subject to the in-year financial position."1

The Scotland Reserve position presented in the FFOR is the same as was reported to Parliament at the time of the Provisional Outturn in June 2021. The expected drawdown from the Scotland Reserve in 2021-22 is £599 million (of which £399 million is resource), which will take the balance at the end of this financial year to £32.1 million.

Impact of Covid-19 on the Scottish Budget

Overview

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a hugely significant impact on the Scottish Budget. To date the Scottish Government has received confirmation of £13.3 billion in Barnett consequentials from the UK Government in respect of the Covid-19 response. The UK Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 identified a further £0.5 billion of Covid-19 Barnett consequentials that are expected for 2021-22, but this will not be confirmed until the UK Supplementary Estimates.1

During the course of 2020-21, an additional £9.7 billion was added to the Scottish spending envelope via Barnett consequentials. £1.1 billion of this money was allocated in February 2021, leaving the Scottish Government with little time to allocate and spend it before the end of March 2021. It therefore requested to the UK Government that it carry forward this sum to the current financial year (2021-22) and so the final Barnett consequential figure for 2020-21 was therefore £8.6 billion (£9.7 billion - £1.1 billion).

In 2021-22, Covid-19 Barnett consequentials have continued to flow into the Scottish Budget, but to a lesser extent than the previous year. £3.6 billion was allocated for 2021-22, with the above mentioned £1.1 billion carried over from 2020-21, taking the 2021-22 total to £4.7 billion.

The following figure sets out the Covid-related Barnett consequentials which have been added to the Scottish Budget at various UK fiscal events over the last two financial years.

| Resource | Capital and Financial Transactions | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 allocated by UK Govt (minimum guarantee) | 8,600 | 8,600 | |

| 2020-21 allocated by UK Govt at Supplementary estimates | 874 | 278 | 1,152 |

| 2021-22 allocated by UK Govt at Spending Review 2020 | 1,328 | 1,328 | |

| 2021-22 allocated by UK Govt at Budget 2020 | 1,206 | 1,206 | |

| 2021 allocated by UK Govt at Main Estimate | 1,000 | 1000 | |

| Total | 13,008 | 278 | 13,286 |

The Scottish Government stated that it has allocated this £13.3 billion plus funds from central reserves and other sources of funding to support the Covid-19 response in Scotland. In total this has resulted in over £13.6 billion in additional funding being deployed. The following figure sets out the Scottish Budget documents where Covid-19 support monies have been formally allocated.

| Resource | Capital and Financial Transactions | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 Budget Revisions | 8,677 | 11 | 8,688 |

| 2021-22 Scottish Budget Bill as amended | 3,593 | 278 | 3,871 |

| 2021-22 Autumn Budget Revision | 1,050 | 1,050 | |

| Total | 13,320 | 289 | 13,609 |

Audit Scotland’s report on ‘Tracking the impact of Covid-19 on Scotland’s public finances: a further update'2 states that the £4.7 billion of Covid-19 consequentials that have been made available for 2021-22 is expected to rise to £4.9 billion at the UK supplementary estimates.

In evidence to the Committee on 5 October, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy confirmed that £328 million of 2021-22 spending is still formally unallocated in the Autumn Budget Revision. She stated that the Spring Budget Revisions will confirm allocations of this and any additional funding confirmed by HM Treasury.3

Tracking Covid-19 funding

In the interests of transparency and effective budgeting, it should be possible to track exactly where the £13.6 billion allocated to the Scottish Government’s Covid-19 response has been spent. With such a fast-moving situation, pieces of information are however spread across a number of documents, making it difficult to follow exactly how much has been allocated to the various Covid-related interventions.

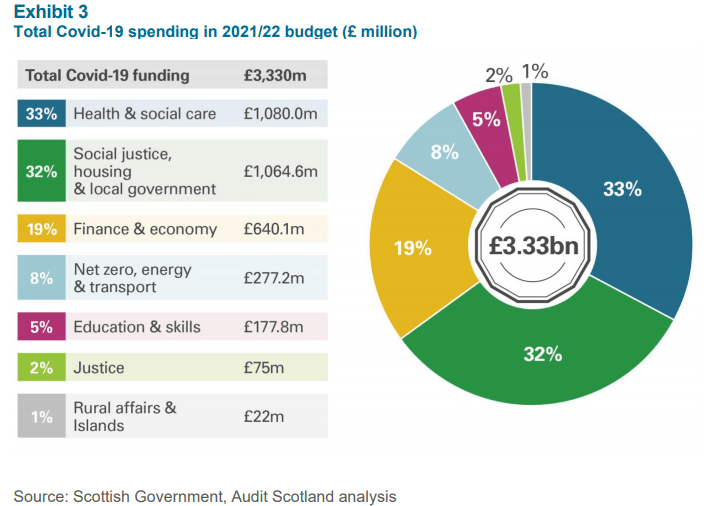

Audit Scotland, in its tracker report, notes that the 2021-22 Budget Bill passed by the Scottish Parliament in March 2021 included provision for £3.3 billion of Covid-19 resource spend, allocated as set out in Figure 7 below.

The Autumn Budget Revision published on 27 September 2021 made Covid-19 allocations of £1,050.6 million which the document states “is funded from a combination of Covid-19 consequentials added at the UK Main Estimate Process and drawdowns from the Scotland Reserve”. This funding was allocated as follows:

| Scottish Government portfolios | £ million |

|---|---|

| Health and Social Care | 834.0 |

| Social Justice, Housing and Local Government | 10.5 |

| Finance and Economy | 46.2 |

| Education and Skills | 30.4 |

| Net Zero, Energy and Transport | 104.5 |

| Constitution, External Affairs and Culture | 25 |

| Total ABR Covid-19 Allocations | 1,050.6 |

In its tracker report, Audit Scotland warns that the ability to separate out ‘Covid spending’ from other areas of spend is likely to become even more challenging as we move into the recovery phase of the pandemic, where spending becomes “linked more widely with economic development and other government goals".1 It argues that “transparency over spending and budget management processes will remain vital”, while SPICe in its blog on Covid-19 funding2 suggests it might become “less realistic” to separate out Covid-19 spend from the wider budget.

As we turn our attention to recovery from the pandemic, the Committee understands that it may become more challenging to identify and track the flow of Covid-19 spend. However, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to commit to providing transparent and timely information on all Covid-19 allocations to allow proper scrutiny of where, and how effectively, the money has been spent, so that any lessons can be learned for the future.

Impact of no Barnett guarantee in 2021-22

In the early months of the pandemic (from March to July 2020) when the UK Government’s budgetary response to the crisis evolved rapidly, it became apparent that the normal operation of the Barnett formula was impacting on the ability of the devolved governments to plan their own budgetary response. In response to these concerns, HM Treasury agreed to provide greater certainty over budget planning by providing an “unprecedented guarantee of additional in-year funding”. The Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee on 5 October that this guarantee gave her “total reassurance that when [funding] was announced, it could be passed on without the fear that the actual sum might be less”.1

No funding guarantee has been provided for 2021-22 Covid-19 related Barnett consequentials. In practice, this means that, should the UK Government not spend all the funding it previously announced, there is a risk that the Scottish Government would not receive all the consequentials it had planned for. The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that “the guarantee has been taken away this year, because the UK Government’s volatility is such that it cannot predict with any certainty what UK departments will spend”. She added: “we manage that volatility internally, but it makes things more challenging and any Government in this role would find huge value in having more tools to manage it”.1

The Committee acknowledges that the minimum funding guarantee of 2020-21 provided welcome certainty for the Scottish Government to announce policies and spending to support those most affected by the pandemic. We note that, despite the pandemic’s ongoing impact, no such guarantee was in place in 2021-22, which has made budget management more challenging.

We therefore reiterate our predecessor Committee’s recommendation that the UK Government should, if the fiscal position rapidly evolves, commit to providing a similar funding guarantee. Longer-term, we believe that there would be merit in both governments reviewing whether this type of guarantee could provide greater certainty for devolved budget planning in the future.

Impact of Covid-19 on the Fiscal Framework

Overview

The fiscal framework agreement between the Scottish and UK governments sets out the funding arrangements, fiscal rules and borrowing powers for the Scottish Government, which arise from the Scotland Act 2016. It determines how funding for the Scottish Budget is adjusted to reflect devolved tax and social security powers, forecasting arrangements, resource and capital borrowing limits, and the Scotland Reserve, which is split into resource and capital components and can be used to transfer money between financial years.1

The framework itself provides that it should be reviewed after the Scottish Parliament elections in 2021 and be informed by an independent report with recommendations presented to both governments by the end of 2021. Last session, our predecessor committee, alongside the Social Security Committee and the Cabinet Secretary for Finance, produced a joint report intended to inform the scope and terms of reference of the body tasked with delivering this independent report. We have not sought here to replicate any of the findings of the joint report in any detail; it should be read as a standalone piece of work based on extensive evidence gathered. We did however recently write2 to the new Chief Secretary to the Treasury drawing his attention to the joint report.

The Committee welcomes the recent announcement that the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury have agreed to commission an “independent report on the Block Grant Adjustment arrangements, including a call for stakeholder input, prior to a broader review of the Fiscal Framework”.3

We note the Cabinet Secretary’s plans to undertake a programme of analysis to inform the broader fiscal framework review, building on the independent report and other key publications and evidence, including last session’s joint report.4 We request regular updates on the commissioning and progress of this independent report.

The Committee further recommends that the independent report should be presented to both the UK and Scottish parliaments, as well as the two governments, as recommended in the Legacy Expert Panel report5 to our predecessor committee at the end of last session.

How has the fiscal framework worked during Covid-19?

The Committee was keen to establish how the fiscal framework has worked during Covid-19. The evidence gathered suggests that the fiscal framework has largely operated as intended. The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) indicated that this was because “Covid-19 has, by and large, had similar health and economic effects across the UK [and] the basic principle of the fiscal framework is that the Scottish budget is protected against the risk of fiscal shocks that impact the whole of the UK in similar ways”.1

It was also suggested by Professor Graeme Roy from the University of Glasgow that “retaining the Barnett formula, which allowed emergency funding to be transferred swiftly to the Scottish Government to support its response to Covid-19" had “provided a significant degree of protection to the Scottish Budget".2 He went on to say that the fiscal framework has ensured the Scottish Government “is able to allocate these funds as it sees fit, with the opportunity to deliver specific Scottish schemes that better fit with the Scottish context”.3

At the outset of the pandemic however, it was not clear as to whether the health or economic impacts of Covid-19 would disproportionately affect some parts of the UK more than others. If this scenario had been realised, the fiscal framework could have seen greater strain and so, both Professor Roy3 and the FAI5 have since argued that the fiscal framework review should consider how such risks could be avoided in the future.

The Committee concludes that the fiscal framework broadly worked as intended during the pandemic, though this was more by accident than design. Whether this remains the case in relation to Scotland’s recovery from the pandemic is something that the Committee will want to return to in future budget scrutiny.

We recommend that the review of the fiscal framework should look at how it can be strengthened to withstand the risk from any future health or economic shocks that could disproportionately affect one part of the UK.

The need for effective intergovernmental relations

We heard during evidence that tensions around funding might have become more acute if there had indeed been a disproportionate impact in one area of the UK. The FAI for example argued that use of Barnett consequentials and the minimum funding guarantee “largely averted major intergovernmental tensions over funding arrangements during the pandemic”,1 while the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE), highlighted that—

A number of things have been done regardless of the framework. Extra funds have been pumped into the Scottish economy to deal with the pandemic. They have been fudged into the fiscal framework as Barnett consequentials but, essentially, the money has been made available. We have the Barnett guarantee, which was never envisaged in the framework. It is the political relationship that is important."2

The SPICe summary of written views states that the lack of effective mechanisms for intergovernmental communication and co-ordination is “a perennial problem with the fiscal framework, and one that has become more evident during the pandemic”.3 More broadly, the RSE submission4 highlights what it considers to be a decline in the state of intergovernmental relations, with the RSE elaborating during oral evidence that possibilities for tension seem to be increasing in light of UK Government spending in devolved areas.5 We further explore the potential impacts of such spending policies later in this report.

We also heard from Professor Roy that “the lack of formal arrangements, developed in more ‘normal times’, to support collaborative decision-making or improved communication on policy areas which are ‘reserved’ is a weakness”.6 At the same time, ICAS made the broad point that recovery will depend on “a more collegiate approach to politics across the UK, Scotland, regional partnerships, and local authorities”.7

The Committee believes that the fiscal framework review presents an opportunity to consider how communication and transparency between the UK and Scottish governments can be improved, to allow more effective management of public finances in Scotland.

We also seek an update from both governments on progress with the ongoing review of intergovernmental relations,8 the timetable for concluding this work, and how its outcomes will impact on the fiscal framework review.

Public understanding, awareness and accountability

Many individuals who responded to the call for evidence were not aware, or had little knowledge, of the fiscal framework, a view that is consistent with recent research exploring public understanding of the budget process more widely.1

Susan Murray of the David Hume Institute told the Committee that “one of the fundamental limitations of the fiscal framework is that so few people really understand it”, adding that it should be made simpler to understand so that more people can engage with it.2 The RSE suggested that “the aspiration for simplicity is always hard to deliver in practice” and in fact the fiscal framework is a simpler mechanism than many other funding formulas or taxes.3 ICAS made the point however that the complexity of the fiscal framework was a barrier to public understanding, meaning “that arguably there is a failure to provide clear public accountability”.4

The Committee believes that the fiscal framework review should look at ways to simplify, and clarify the workings of, the fiscal framework where possible, to improve public understanding and public accountability. We believe that, as a starting point, both governments should commit to providing transparency and enabling Parliamentary scrutiny of their decision-making at key stages during the review process.

Reserves, borrowing and forecast error

Under the fiscal framework, the Scottish Government has the power to borrow up to £600 million resource borrowing each year, within a statutory overall limit of £1.75 billion. Resource borrowing can only be undertaken for: in-year cash management, with an annual limit of £500 million, or for forecast errors in relation to devolved and assigned taxes and social security expenditure, with an annual limit of £300 million (increasing to £600 million in the event of a Scotland-specific economic shock). It is also able to borrow up to £3 billion for capital spending, with an annual limit of £450 million.

The Scottish Government is also able to build up funds in, and draw down funds from, the Scotland Reserve, which is capped in aggregate at £700 million, and limited to £250 million annual drawdowns for resource and £100 million for capital. There are no annual limits to payments into the Scotland Reserve up to the cap of £700 million. In the event of an economic shock, the drawdown cap is removed, although this does not change the overall limit of £700 million.

Forecast error is widely understood to be one of two broad risks to which the Scottish Budget is exposed through the fiscal framework.1 The other, explored later in this report, arises if the income tax base grows relatively more slowly than the equivalent income tax base in the rest of the UK.

Put simply, if the Scottish Budget is based on a set of forecasts that turn out to have overestimated the level of funding available to the Scottish Government, then a subsequent budget will need to address any shortfall. The uncertainty from Covid-19 has brought much greater volatility to forecasting.

One difficulty cited by the SFC was that the outlook for the economy, taxes and social security could differ significantly from its forecasts if, for example, a serious fourth wave of cases brought further restrictions, or if a significant new strain of the virus resistant to vaccines, was to emerge. According to our budget adviser, estimates are also subject to “a much higher degree of uncertainty right now due to the difficulties in collecting some of the data used to estimate GDP and the faster timetable of production of the estimates”.2 This, she explained, had led in the short-term, in some cases, to UK data being used as a proxy for the experience of Scottish firms where Scottish specific data is not available.2

The SFC’s August 2021 economic and fiscal forecasts included, for the first time, an estimate of spending on the new Adult Disability Payment (ADP) due to replace the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) from summer 2022. The risks of forecasting a new benefit adds further volatility for the Scottish Budget for 2022-23. The SFC explained that this is due to there being limited information on how many people will be eligible, who will claim, and on which to estimate the additional costs of ADP.4

Timing differences between economic forecasts from the OBR and SFC present a further challenge. In January 2021, the provision in the fiscal framework which triggers a Scotland-specific economic shock was met, due to the quirk in timing of the two sets of forecasts. The shock allows the Scottish Government more scope to borrow to cover forecast error over the next few years.

The SFC noted that conditions for the economic shock were, however, no longer present in the comparison of its August 2021 GDP forecast to the OBR’s March 2021 GDP forecast, but the relaxation of limits would however still apply to financial years 2021-22 to 2023-24.4 Professor Roy warned the Committee that “it surely cannot be the case that funding flexibilities are either available or not available based on the date of publication of a report”. He called for the fiscal framework review to consider the timing of forecasts, as well as the budget and parliamentary scrutiny, that underpins an effective budget process.6

There was general concern that the ability of the Scottish Government to borrow to deal with annual fluctuations within the fiscal framework is “pretty limited” and relatively lower when compared with the Welsh Fiscal Framework.7 The FAI’s view was that there is “an obvious or strong case for saying that those limits on forecast error borrowing are insufficient [and that] similarly, the drawdown limits and the cap on the Scotland Reserve are not particularly generous”.8 He suggested this was an area where “you would hope that the Governments could quickly agree at the very least that those existing constraints need to be addressed”.8

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that “it is hugely detrimental to have an arbitrary cap of £300 million for forecast error”, arguing “it reduces our ability to plan ahead and it means that when forecast error exceeds £300 million, … actual money that could otherwise be used for public services must be used to deal with the forecast error”.10 She went on to suggest that the Scottish Government should “have limited ability to carry forward and manage the budget across years”, as recommended by the Committee’s predecessor.11

Since the fiscal framework sets out the borrowing and reserve limits in nominal terms, there is no mechanism to adjust the limits as the Scottish Budget changes year-on-year. Without this protection against inflation, the real-term cash value of the Government’s borrowing and reserve powers has therefore fallen over time.12

The Committee during evidence explored the merits of a prudential framework for capital borrowing, similar to the one available for local authorities, which allows councils to borrow what they can afford, with no arbitrary limit. Alan Russell from Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) explained that the approach “is critical in allowing local government to invest affordably and sustainably”, adding he could “see how attractive it would be for the Government to consider having a scheme of that nature operating at a national level”.13

When asked whether the Scottish Government would be looking for limits on borrowing to be index-linked to inflation, Ms Forbes responded “at the very least, but basing limits on affordability rather than arbitrary caps would be my default position”.14

The Committee considers that the Scottish Government should have more flexibility to carry forward and manage its budget across years in normal times. We look forward to exploring this matter further.

We believe that the limits on the Scottish Government’s resource borrowing powers to cover forecast error and cash management, and the Scotland Reserve, are not currently sufficient. We consider that these should, as a minimum, be linked to inflation.

The Committee agrees with our predecessor that the two governments should consider the extent of the risk arising from potential divergence in forecast error between the SFC and the OBR, learning any lessons from the experience of an economic shock being triggered due to a quirk in timings.

Recent publication of the UK and Scottish government budgets has followed a different timeline than was envisioned when the fiscal framework was agreed, which has created additional volatility and uncertainty for the budget process. We believe that greater co-ordination regarding the two governments’ budget timings is needed.

Noting recommendations from both the Smith Commission and our predecessor committee, as well as evidence gathered during our inquiry, we consider that it is now time to revisit the merits of a prudential borrowing scheme for capital borrowing.

The Committee recommends that these issues are considered as part of the upcoming fiscal framework review.

Income tax

Through the fiscal framework, the Scottish Budget is exposed to the broad risk of the income tax base growing relatively more slowly than the equivalent income tax base in the rest of the UK.1 If this happens, Scottish revenues are likely to be lower than the block grant adjustment and therefore, the Scottish Budget is worse off than it would have been had tax devolution not occurred.

The fiscal framework protects Scotland against its relatively slower population growth as it operates on a per head basis, but it does not take account of the fact that the total population may become less “working age rich” with a smaller working age population than the rest of the UK. There are significant differences in the distribution of the income tax base in Scotland compared with the rest of the UK which also poses a notable risk to the Scottish Budget, albeit to a lesser extent than differences in economic performance. Most importantly, according to the FAI, there are relatively fewer high-income taxpayers in Scotland than in the rest of the UK and their earnings are also typically lower.2

The impact of potential differences in the Scottish income tax base compared with the rest of the UK can be seen in the provisional outturn figures published in July 2021 by HMRC.3 When the Scottish Government published the 2019-20 Budget in December 2018, it estimated that its income tax policy would raise around £500 million in additional revenues compared to the case if Scotland implemented the same income tax policy as in the rest of the UK. However, the outturn figures for 2019-20 show that only £148 million was raised.

The FAI explained that this difference may be due to “a legacy of things that were happening in the offshore sector, which have a disproportionate impact on the Scottish economy and Scottish income growth relative to the rest of the UK."4 It further suggested that this could have been ‘baked in’, having arisen from slower tax base growth in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK during the first two years of income tax devolution.5 As such, Scotland’s tax base has not necessarily grown more slowly, but rather this difference has persisted.

Fiscal Sustainability

Demography

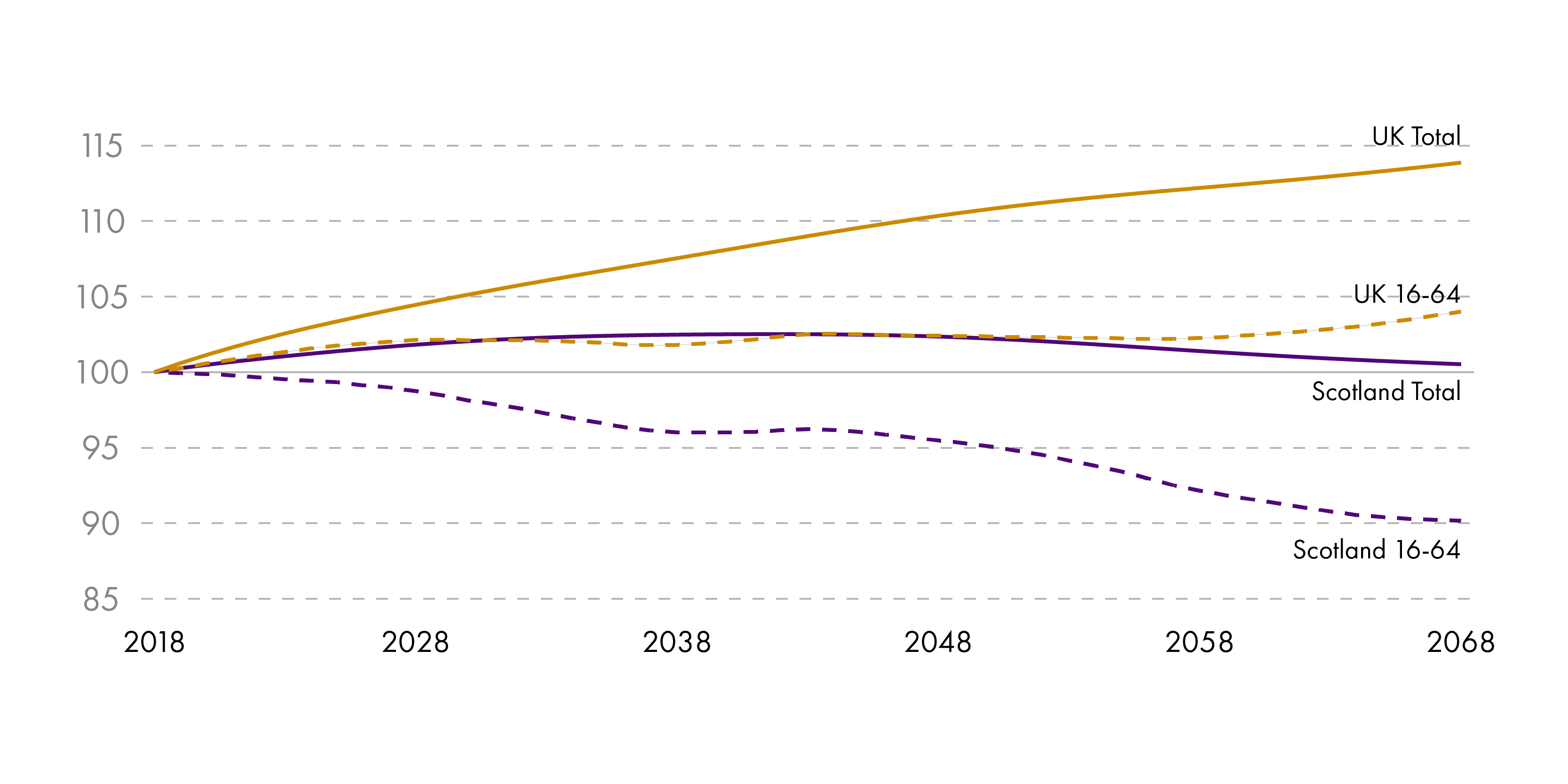

Fiscal sustainability, according to the OECD, is the ability of government to maintain public finances at a credible and serviceable position over the long-term.1 Demographic change in Scotland continues to be a particular risk to fiscal sustainability with the latest forecasts from the SFC expecting the Scottish population to decline by 15,000 over the next five years and the population aged 16-64 to fall by 60,000 people in the same time period (see figure 9). Birth rates have also been falling, with Covid-19 repercussions likely to reduce them even further. While migration is expected to recover from “the extreme low levels in 2020 and 2021” it will “remain below pre-2019-20 levels for the foreseeable future, due to the UK’s exit from the EU".2

The SFC explains that the reduction in working age population will be a “curb on growth on the total size of the Scottish economy” and in the longer term it is expected to act as a drag on GDP per capita. In contrast, the population aged over 65 in Scotland is projected to continue to grow by over 110,000 between 2020 and 2026, leading to an expected increase in spending on social security payments related to ill-health and disabilities more present in an aging population.2

This outlook presents particular challenges for the Scottish Government in the fiscal sustainability of its policies in relation to demand-led services and social security payments. Recent analysis by the SFC suggests for example that the new social security payments being introduced to replace the PIP and ADP, as referred to earlier in this report, are likely to generate £0.5 billion additional spending over and above what would have been paid through PIP.2 While these estimates are currently uncertain, our adviser notes that this could impact on future fiscal sustainability.5

The Scottish Government’s third Medium-Term Financial Strategy (MTFS), published in January 2021, states that, although this demographic change is gradual over a number of years, “policy interventions are required earlier in order to maintain the affordability of health care and the pension system over the long term”.6 It goes on to explain that for health “this requires both more efficient service delivery as well sustained and concerted action to reduce demand through self-care, prevention and health improvement."7

According to the Cabinet Secretary, the primary way to increase public revenue in order to fund public services is through broadening and increasing the tax base. To do this the number of people in fair, well-paid secure employment needs to be maximised.8

The Committee notes that the demographic projections present a double ‘whammy’ to fiscal sustainability, as the proportion of working age people falls while the number of over 65s continues to grow. The provision of public services and welfare payments would, in this scenario, need to be funded from a smaller and more productive working population.

We recognise that reversing these demographic trends will require a focused and sustained approach to policy-making over a number of years. We therefore seek clarification from the Scottish Government as to how this challenge will be addressed in its Budget 2022-23, and its next Medium-Term Financial Strategy, which looks ahead to the next five years.

The Committee also notes publication of the Scottish Government’s strategy ‘A Scotland for the future: opportunities and challenges of Scotland’s changing population’ in March 2021.9 We seek an update on progress in delivering its recommendations, including its proposal for a Demographic Commission.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s preparatory work to start producing a fiscal sustainability report each session, which would look ahead to the next 30 to 50 years and identify “particular pressures on spending or revenue arising from, for example, population growth”.10 We agree with the SFC that this presents a real opportunity to “consider whether major alterations will be required to adjust for changing circumstances”10 and we therefore ask the Scottish Government to support the SFC in this important work.

Joined-up thinking

The Committee heard during evidence about a number of Scottish Government strategies and plans which have been recently produced, or are soon to be so, all with a bearing on the economy and fiscal sustainability. This includes a Covid-19 recovery strategy published in October, a 10-year National Strategy for Economic Transformation due “in the next few months”, as well as the Framework which precedes a resource spending review, the next five-year MTFS, and the Scottish Budget itself all being published in December. The Scottish Government further describes the National Performance Framework (NPF) as a longer-term vision steering how it will lead Scotland out of the pandemic.1 The Committee heard that this landscape was becoming complicated and far from ‘joined up’, including from the FAI which suggested “we are throwing far too many assessments at things” and questioned “how all those things fit together and influence action is not particularly clear”.2 The RSE told the Committee that Government policy on growing the economy had “been quite confused, sometimes very dispersed and very bureaucratic”.3

There were also calls for the NPF, which “guides” all government decisions and actions, to be more closely linked to the Scottish Budget, with greater clarity and explanation as to why certain spending decisions are made, and why some budget lines receive greater priority than others. The David Hume Institute (DHI) argued in its written submission that “budget priorities should be directly linked to the progress for all of the NPF outcomes, which should be tracked regularly” and that “the budget should be clear on the interdependencies between different investment priorities and look for efficiencies across budget boundaries”.4

The Cabinet Secretary agreed that the Scottish Government’s budget choices need to be aligned to the National Performance Framework.5

We believe that more efficiency can be achieved by streamlining and linking up the various strategies and plans which have an impact on growing the economy and fiscal sustainability as we move out of the pandemic. We ask the Scottish Government to outline how it will make progress on this matter.

The Committee considers that the upcoming statutory review of national outcomes provides an opportunity to reposition the National Performance Framework at the heart of government planning, from which all priorities and plans should flow. We also ask the Scottish Government to consider how the NPF could be more closely linked to budget planning.

Multi-year funding

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that the majority of her plans are for multi-year projects, and so it was important that the government was able to carry forward, and be able to manage, money over several years, rather than having “an arbitrary break at the end of the financial year”, which she suggested “leads to very ineffective budgeting”.1

The greater certainty that multi-year funding provides is also much sought after by local government, the third sector and other stakeholders. The joint submission from COSLA, SOLACE and CIPFA suggested that annual budgets saw them being “pressed into areas of specific spend or to be limited to using funding by an artificial deadline or within a financial year”.2 Councillor Gail Macgregor, Resources Spokesperson at COSLA, told the Committee that the shortfall in funding created by a loss of income and additional Covid-19 demands was exacerbated because of single-year budgets, whereas a multi-year budget would have brought more stability and an ability to move things around.3 SCVO also called on the Committee to investigate progress in moving to multi-year funding.4

The Low Incomes Tax Reform Group agreed with this position, but acknowledged the challenges of adopting such an approach, particularly where the Scottish Government was not aware of what might be in the UK budget.5

The Cabinet Secretary said she recognised the importance of multi-year funding to local authorities, the third sector and bodies such as the NHS, and confirmed that work was progressing “right now to develop a sustainable, multiyear financial plan” to reduce the risk of having to “lurch from one year to the next.”6

Since the Committee took evidence, the Chancellor of the Exchequer on 27 October 2021 announced the UK Government’s first multi-year Spending Review since 2015, setting out funds for individual UK departments and the devolved administrations for the next three financial years, 2022-23 to 2024-25.

The Committee believes that multi-year budgets are crucial to securing certainty for Scottish public finances, including for local government, the third sector, and other key bodies. We acknowledge that it can be more challenging to deliver this approach in situations where the Scottish Government does not have confirmed multi-year block grant funding from the UK Government. We therefore recommend that both governments consider how multi-year budgets can be achieved more routinely as part of the fiscal framework review.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out in its framework document due in December further details of its resource spending review and how this might bring more certainty and efficiency to budgeting arrangements in the future.

Continuing challenges for the Scottish Budget

Spending priorities

While there are not yet signs that the overall pandemic impact on the Scottish economy has been different to the rest of the UK, it has, however, “had very uneven health, financial and other economic impacts”1 and has disproportionately affected certain sectors, demographics and geographies.

We heard from a number of witnesses that the pandemic has in particular exacerbated pre-existing inequalities and we received specific calls for funding in these areas. Age Scotland, for example, argued that the Budget should include measures to assist with pensioner poverty, citing more people than ever being pushed into fuel poverty and loneliness during the pandemic.2 At the other end of the spectrum, we heard from the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) that their top priority in this year’s Budget should be the doubling of the child payment.3 Wider investment in childcare, housing and fair employment was also needed to help ensure that child poverty is reduced in line with targets by 2023-24.4

Alcohol Focus Scotland (AFS) highlighted that the pandemic and social restrictions appeared to “be polarising drinking habits in Scotland, with the real risk of widening existing inequalities in alcohol harm”. It called for the price of alcohol to be increased along with additional investment in recovery services.5

The impact of the pandemic on women is well-documented, with women far more likely to have primary caring responsibilities and around a third more likely to work in those sectors that have been shut down or restricted.6 There were calls from the CPAG to “prioritise increasing the security and adequacy of women’s earnings”7, while the ALLIANCE agreed that the Budget should ensure “an economy that works for women”.8 The Scottish Women’s Budget Group called for “gender analysis of the policy and resource allocation process in the budget [which] means examining how budgetary allocations affect the economic and social opportunities of women and men, and restructuring revenue and spending decisions to eliminate unequal gendered outcomes”.9

We also heard that Covid-19 had impacted on a wider demographic than those traditionally experiencing inequality or poverty, with Citizens Advice Scotland indicating it was seeing more people in employment, younger and living in the least deprived areas compared to more regular CAB clients. This, it argued, shows the wide impact of the virus and the need for “a strong safety net for people going forward”, adding “the Scottish Budget should include measures to grow the economy, prevent people falling into poverty and giving people more spending power, particularly those on lower incomes and newly indebted”.10

These calls for spend come against a background of tightening budgets this year, and potentially throughout this Parliament, with demand expected to outstrip the funding available.11 While few organisations were able to say where money could be found to fund their spending priorities, AFS did suggest introducing a new levy to the sale of alcohol “in the off trade” and a public health supplement to non-domestic rates for retailers who sell alcohol, as ways of funding their preferred interventions.5 AFS and others, such as Age Scotland, also highlighted the need for preventative spend, with the latter welcoming the Scottish Government’s ‘Tackling Loneliness Fund’ of £10m as an example of where preventative measures can “allow more people to live well for longer and save costs from health interventions”.2

The need for action on climate change is not only crucial to protecting the planet, it can also be viewed through the lens of preventative spend, as it limits the need for significant funding to respond to devastating impacts. The UK Committee on Climate Change suggested that reaching net zero emissions by 2050 would cost less than 1% of GDP every year through to 2050.14 The Scottish Government’s commitments to net zero by 2045 are therefore welcome and COP26 taking place in Scotland during November 2021 provides an opportunity for global action in this regard. However, Linda Sommerville from the STUC told the Committee that “if we want to be a net zero nation … there has to be significant change in how we structure our economy, … and we have an opportunity with this and successive budgets, to set the direction that we want for that”.15 She highlighted that increasing “tax through wealth taxes, as well as through business taxes, should be considered as a possible way to fund these measures”.16 However, no further details were provided to explain these proposals.

The Cabinet Secretary indicated more broadly that there was an opportunity to put more investment upstream for preventative measures in a significant way with the resource spending review, because that will be multi-year, adding that this “will allow us to look at how the compounding effect of multiple years delivers that change”.17

The Committee understands that public finances will be under significant pressure in the next few years and that the Scottish Government faces difficult decisions on how it prioritises spend and raises revenue. We further realise that it will not be possible to address the consequences of Covid-19 within the short planning horizon of just one budget round. We therefore recommend that the Scottish Government explores within its next resource spending review and Medium-Term Financial Strategy, which policy interventions would have the greatest impact on cross-cutting issues such as addressing inequalities and poverty.

We can see real economic and societal benefits in prioritising spend for preventative measures, whether that be to protect the environment or the health of the nation in future years. We believe that the resource spending review provides an opportunity to introduce bold preventative measures to protect funds and create a wellbeing economy for the long-term.

Many of our other recommendations in this report are intended to achieve greater fiscal sustainability, which we believe would allow more preventative spend to be identified and allocated in future years.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out in the Scottish Budget 2022-23 and Medium-Term Financial Strategy how it intends to manage the economy to meet its net zero commitments by 2045. Examining the finances behind the net zero targets is an issue we intend to return to in early course. This may also be an area which the Scottish Fiscal Commission will wish to consider as part of future fiscal sustainability reports.

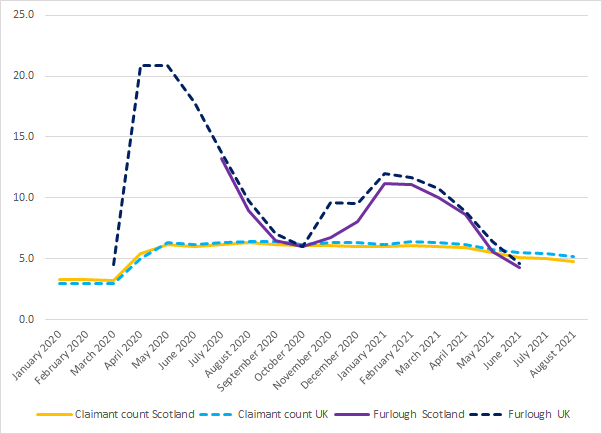

The SFC explained in its August forecasts that throughout the pandemic, the labour market has performed better than might have been expected, in part because of the success of job support schemes and business support schemes. It stated that “we now expect the unemployment rate to peak at 5.4 per cent in 2021 Q4 after the furlough scheme expires on 30 September 2021, compared with 7.6 per cent in 2021 Q2 in our January 2021 forecast”.18

The SFC predicts that employment will grow by 1% in 2021-22 but with growth falling in subsequent years as the outlook looks uncertain. Nominal Earnings growth is however revised up because of the improved economic outlook and higher inflation. As a result, income tax revenues have been revised up across the forecast period because of higher average nominal earnings growth.18 It acknowledges that it may be taking an overly optimistic judgement of the economic scarring of the pandemic and that the “long-term damage to the economy could be greater than we are forecasting.”20

The OBR in March 2021 stated that the pandemic impact on employment and earnings has varied greatly across households, “with some experiencing dramatic falls in income and rising debt while others, whose incomes were unaffected but whose opportunities to spend were curtailed by lockdowns, have saved unprecedented amounts.”21 It goes on to suggest that, alongside the negative impact of net outward migration over the past year, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the future size of the workforce due to continuing lower net inward migration and the effect of the pandemic on participation and hours.22

The DHI highlighted research that “for the first time in the past few years, Scotland has net migration from the rest of the UK”, suggesting that this may be one way to quickly address skills gaps,23 though this assumes that those migrating are of working age. The DHI also explained that, “at a time when tax receipts will be crucial, prioritising support for jobs where skills can be developed, rather than skills development alone, will be critical.”

The ending of the furlough scheme and the Self Employment Income Support Scheme may impact unequally across the working age population and it is as yet unclear how many of those on furlough when the scheme ended, have gone to secure fair work. That said, again, there has been no evidence to suggest that the impact on Scotland may be different to that of the rest of the UK (see Figure 10).

The STUC highlighted how labour market inequalities had been exposed as a result of the pandemic with “young people and women - particularly those in lower paid jobs and those who work part time – more likely to end up on furlough as were black and minority workers.”24

Research by the IFS identified that across the UK the employment opportunities for those made redundant during the pandemic may differ according to age with the trends affecting workers aged 60+ especially worrying. It found that “among those made redundant during the pandemic, 58% were not in, or searching for, work six months later, compared with just 38% among those made redundant in the three years prior to the pandemic”. There is a risk that older workers made unemployed after furlough may drop out of the labour force altogether.25

This is echoed in evidence we received from Age Scotland who also highlighted the risk that such people may potentially use their pension savings to bridge the gap, “leaving them in poverty or on a lower income for far more of their life.” It went on to call on the Scottish Government to support better working conditions such as flexible working, support for people who are carers or better intergenerational teams to fully utilise this “untapped resource” that could meet the current skills shortages.26

Alongside rising unemployment, we heard of increasing numbers of vacancies. The IFS explained that, in August 2021, the number of vacancies in Scotland was over twofold greater than last summer – the fastest growing in the UK. The IFS observed though that “although an increase in vacancies is a positive sign of Scotland's recovery, there are growing concerns of a mismatch between the skills demanded for vacancies and the skillsets of those searching for jobs.”25

Explanations for this increase in vacancies included “the furlough scheme ‘freezing’ the reallocation of labour, some jobs becoming less attractive during the pandemic, and reductions in the numbers of EU nationals working in the UK.” The IFS stated that although high vacancies might allay concerns about unemployment, the industries with the highest number of vacancies are not the ones with the highest numbers of unemployed or furloughed workers (who face risks of unemployment in the future). To address this mismatch, sectoral or geographical labour reallocation policies may be needed in the coming years.25

In its ‘Covid Recovery Strategy: for a fairer Scotland’29, the Scottish Government sets out its vision for recovery from the pandemic, which seeks to deliver three outcomes: financial security for low income households, wellbeing of children and young people, and good, green jobs and fair work. It confirms that a new 10-year National Strategy for Economic Transformation will be published later this year which will set out the longer-term steps to deliver a green economic recovery.29

The Cabinet Secretary said she recognised the real challenges in relation to people who face redundancy, or who have been made redundant because their industries are changing. She highlighted the National Transition Training Fund which seeks to provide funding to particular sectors as the primary way of supporting older workers who are unemployed, at risk of redundancy, or in need of upskilling or retraining. Other programmes aimed at supporting those furthest from the job market include the No One Left Behind scheme.31

There remains, however, the challenge of encouraging take-up of vacancies in some sectors where the Cabinet Secretary recognised that improving terms and conditions and pay can help make such work more attractive to job seekers. In that regard the Scottish Government will provide support financial or otherwise but “that work is very much industry led and that is important.”32

The Cabinet Secretary explained that the Scottish Government is working with industry on labour market shortages but that, whilst it can provide skills interventions, the “acute labour shortages that we face right now are largely to do with immigration policy, over which we have no control.” It is therefore engaging closely with the UK Government on this issue as well as the issues with the supply chains, another factor that has meant the pace of recovery is uneven across sectors.33

The Cabinet Secretary observed that, if Scotland is not able to access additional labour from outwith the country, “it is even more imperative that we invest in innovation and tech and that we improve productivity levels across the country… and that includes investing in our people.”34

Growth in income and employment are key ways of improving Scotland’s tax performance relative to rest of the UK. There is no doubt that Covid-19 has exacerbated labour market inequalities and its full impact will only become clear with the ending of furlough and the self-employment support scheme.

What is emerging is a complex picture of higher unemployment for some sections of working age population alongside increased vacancies in some sectors which are proving challenging to fill. Addressing this mismatch will be important in growing Scotland’s tax base particularly given its demographic challenge.

We note that the Scottish Government’s Covid Recovery Strategy sets out a range of commitments to reskill and retrain people, as well as support for the creation of jobs. In view of the evidence we received, we believe that the Scottish Government should also look to provide targeted schemes to support older workers into work, to ensure a fair and equal recovery.

We recognise that addressing skills shortages is only one half of the challenge; ensuring businesses provide secure, good quality employment is equally important. In line with the Scottish Government’s stated priority of building a wellbeing economy, the Committee seeks an update on how it will broaden access (including for older people) to a high standard of employment through its Budget 2022-23 and next Medium-Term Financial Strategy.

As the SFC highlighted, there are also “ongoing international supply pressures which combined with domestic recruitment challenges present risks to our forecasts.”18 This then impacts on inflation as we set out below.

Inflation

Inflation is a measure of the rate of rising goods and services in an economy. It can be caused by increases in production costs or supply pressures or increased demand for products or services. It means that consumers’ purchasing powers are reduced and it may deter spending from those who have that choice. Before the pandemic, inflation was around 2%, which is the rate the Bank of England aims for.

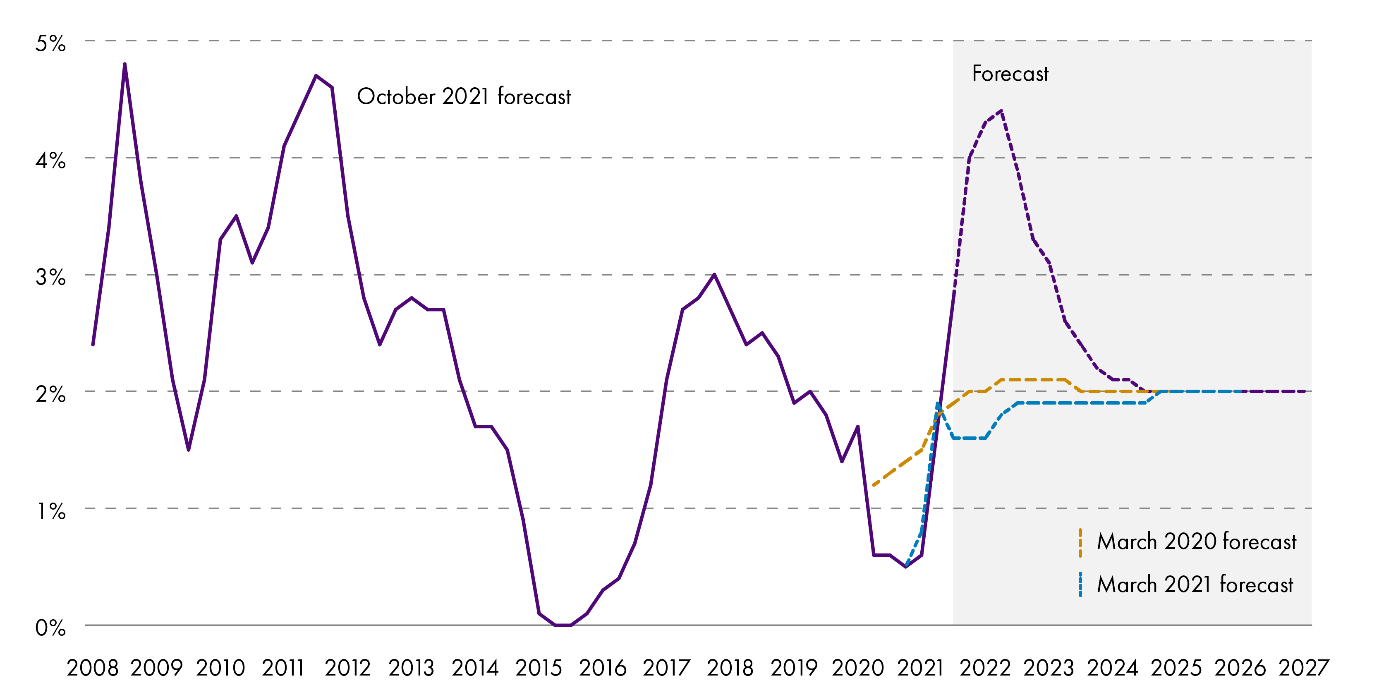

The Committee however heard from the SFC that inflation has been rising over the last year (see Figure 11 ). Our adviser explained that “whilst demand is rising at a fast pace as the economy reopens, supply is constrained in some sectors because of both supply chain issues and labour shortages.”1 To be as up-to-date as possible at the time, the SFC aligned its forecasts to the more recent Bank of England predictions of inflation, rather than the March OBR forecasts.

The SFC revised its tax forecasts upwards in August 2021 compared with its forecasts from January 2021, in part due to rising inflation. This also impacted on social security, with the SFC predicting that, along with demographic change “spending on devolved payments will increase from £3.7 billion in 2021-22 to £5.2 billion in 2026-27, as more people receive support each year and payments are uprated by inflation.”2

Our adviser explained in August 2021 that “the Bank of England is still taking the view that this is transitory, and that inflation is likely to peak at the end of the year at 4% before tracking back to the 2% target over the course of 2022.”1 In its October outlook, the OBR reports that “the near-term spike in inflation next year is expected to be relatively short lived, with inflation returning to the 2 per cent target in 2024, as energy prices stabilise, supply bottlenecks ease, and a modest tightening in monetary policy counteracts the extra stimulus from the fiscal package.”4

The increase in inflation has had a significant impact on the forecasts for income tax in particular. In future years, as thresholds are likely to be frozen in real terms, fiscal drag is likely to both bring more Scottish earners into tax, and more earners into the top rates of tax.1 The SFC argued that this effect will be the same for the rest of the UK as for Scotland “so the actual net position will not be so large.”6

Pay is a key driver of public expenditure and makes up around half of the Scottish resource budget. The Scottish public sector is proportionally larger (at 19%) than the UK average of 17%, with the average in England being 15% (as of 2020 Q3).7 The relative larger size of the Scottish public sector carries with it a greater fiscal risk to the Scottish Budget, particularly in the context of the Barnett allocation, which is determined by population share and must be distributed over a comparatively larger workforce.8

Inflation is one of the factors the Scottish Government considers alongside trends in private and public sector earnings, and wider unemployment levels when setting public sector pay policy.7 As the Cabinet Secretary explained, the UK Government’s approach to pay policy also impacts on the Scottish Budget, as “if the UK Government pay is flatter, we obviously do not get additional consequentials from that either.”10

Public sector pay policy negotiations will take place towards the end of the year when inflation is anticipated to be at around 4%, and as such will be an important issue for the Scottish Budget.

Alongside the impact of inflation on public sector pay, the Cabinet Secretary recognised that inflation will also impact on costs and “we cannot escape its impact if we are to achieve our policy aims or build the infrastructure that we want to build.”11

The Committee recognises that higher inflation can bring with it increased income tax revenue, but that this must be balanced in the Scottish Budget with higher costs and spend on pay and social security.

We ask the Scottish Government if it has assessed the implications for the Scottish Budget of higher inflation rates continuing into the medium-term, particularly given Scotland’s demographic position. We would also welcome clarification as to how the Scottish Government intends to reflect the uncertainty of inflation rates in its public sector pay policy.

Sectoral impacts and behavioural change

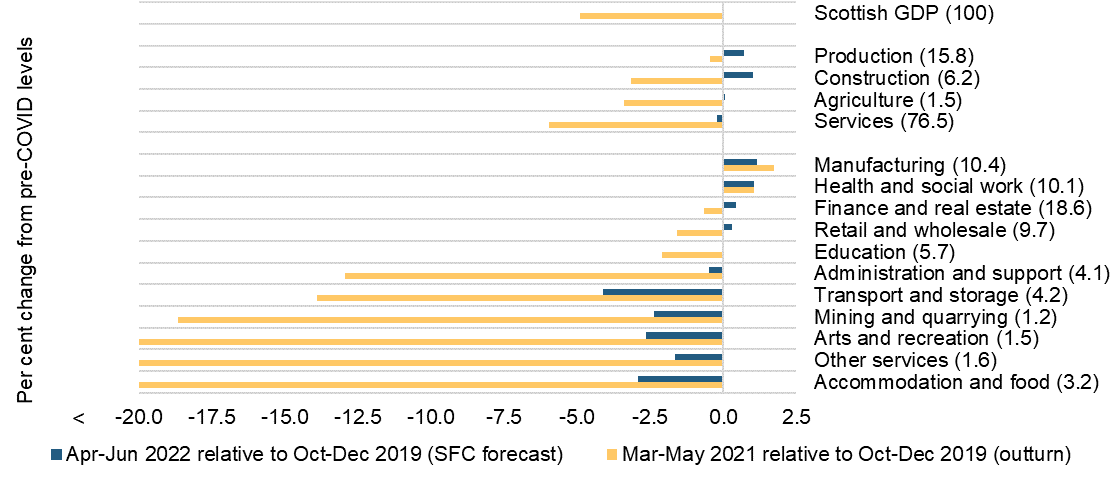

The SFC’s August forecasts noted that “a feature of the Covid-19 economic crisis is that some sectors are disproportionately affected, with hospitality and leisure being most exposed. It argued that “it is possible that economic recovery will also have an asymmetric nature, with the reopening or catching-up of the sectors which were hardest hit by the shock also driving the recovery”. On average over 2022 Q2, when it expects Scottish GDP to have returned to its pre-crisis level, the hardest hit sectors will have regained much of the lost output, although they may still be below pre-Covid levels. It highlighted this may especially be the case for the transport sector, affected by lower levels of commuting by public transport and lower international travel.1

Figure 12 from the SFC August 2021 forecasts shows the GDP change from pre-Covid-19 levels, with relative weights as percentages of GDP shown in brackets.

The SFC expects that the pathway out of the pandemic is “unlikely to be completely smooth”, with businesses and households taking time to adjust to a new normal and ongoing international supply pressures combined with domestic recruitment challenges. On a more positive note, John Ireland from the Scottish Fiscal Commission told the Committee that “the sectors with strong growth will to some extent be mitigated by the sectors with slower growth so we might see some greater stability at the aggregate level than we would if we look at the detail underneath”.2

As we refer to earlier in this report, household savings have “massively” increased throughout the pandemic. The SFC expects households to spend some of the savings they have accumulated and so it forecasts savings will fall to 8% in 2021, down from its peak of 28%. This spending is not expected to have a medium or long-term impact on the economy. Dame Susan Rice warned however that “people could hold back on big spending decisions or they could consider where they live or whether it is time to change jobs and take a risk”, adding “there are lots of ways in which uncertainty could impact on decisions, and those decisions will have an economic impact”.3

Professor Breedon from the SFC added “it is right that we will have a period when spending patterns will flip around”, with investing replaced by more standard consumption patterns as the economy recovers, “so we will see sectors such as hospitality and recreation stepping up to take over where spending has been dominated by durable consumption at the moment”.4

The Committee heard that some businesses that had survived the lockdown were now operating in very different circumstances than before the pandemic, having accumulated significant sums of debt. The Scottish Chambers of Commerce (SCC) expressed particular concern that the end of business support measures is a “moment of maximum danger for many businesses” and are calling for the 2022-23 Budget to include commitments to longer-term business support and assurance that all sectors of the economy will have access to this. The SCC is also looking for the expansion of rates relief to more sectors and businesses that will take longer to recover, as well as additional business grants provision if required”.5

With retail an area particularly hard hit by the pandemic, the Scottish Retail Consortium noted that the viability of some stores remains uncertain and, even now, footfall especially in the city centres is significantly lower than pre-pandemic levels. It asks that the Scottish Budget “provide[s] early certainty for firms, reignites consumer spending, and keeps down the cost of doing business”, highlighting in particular the benefits of a high street voucher scheme similar to the one being introduced by the Northern Ireland Executive to trigger spending.6

To encourage investment into our high streets, the Scottish Property Federation has called for key reforms to property taxation and a reduction or removal of charging empty property rates on shops and other business properties that often simply cannot be re-let due to wider economic conditions.7

With regard to non-domestic rates (NDR), the Scottish Government provided 1.6% rates relief for all properties from 1 April 2020 for one year, effectively reversing the change in poundage for 2020-21. In addition, 100% rates relief was introduced for retail, hospitality and leisure sectors, and all airports, for the same time-period. The SFC highlighted in its August 2021 forecasts that NDR revenue in 2020-21 was £933 million or 34% lower than it had forecasted in February 2020.8The FAI suggested that there might be “scope to look at some of those reliefs as a source of revenue in the longer-term.”9

The Cabinet Secretary said she recognised the importance of businesses performing well to provide a secure long-term source of revenue from NDR, indicating that a full year of relief was intended to maximise the time for industry to recover. She added, “as we go into the budget, we will be very cognisant of the need to ensure that our taxation enables businesses to fully recover and fully trade”. However, she did not see any “huge room for manoeuvre” in terms of business taxes “just now”10. CIPFA however noted that, while NDR is currently managed effectively at national level, there could be opportunities to explore greater flexibilities to allow councils to respond to local priorities, or other approaches to funding local services.

More generally, with regards to local authority funding, COSLA explained that, due to Barnett consequentials, local government had been able to “plug a fair amount of the gap” of £500m funding it had predicted in the Budget 2021-22. However, councils had faced reductions in revenues generated through charges for services and facilities and this lost income was “very significant”.11 CIPFA confirmed that “prior to the pandemic, a number of councils were certainly coming under increased pressure and beginning to rely on their reserves as part of addressing the balance of their budget.” While the situation had improved in the last year as a result of Covid-related funding, CIPFA expected that “reserves will be significantly depleted as we move through this financial year”.12

The Committee heard that work was underway on developing a fiscal framework between the Scottish Government and local authorities, which Alan Russell from CIPFA told the Committee should provide “the flexibility to spend and raise money locally, where we can”.11 Councillor Gail McGregor from COSLA added in terms of timescales that she hoped a local government fiscal framework could “dovetail” with the fiscal framework review. Though she acknowledged there may be some “low-hanging fruit” reached in the short-term, but medium and long-term planning would also be needed to consider issues such as council tax replacement and so, “we are probably looking at five years”.14

The Committee recognises the impact of the pandemic on many businesses, including the hospitality, retail, leisure and travel sectors, some of whom have built up significant debt. We ask the Scottish Government to consider how it might best support these sectors to recover, rejuvenate the high street and grow the economy.

We recognise that the two non-domestic rates reliefs put in place by the Scottish Government for the year 2020-21 provided much-needed support to those businesses struggling the most. While we appreciate that it may not be sustainable to plan for similar reliefs within the 2022-23 Budget, we welcome the Cabinet Secretary’s commitment to be “cognisant of the need to ensure taxation enables businesses to fully recover and fully trade”.15

The Committee understands the continuing pressures on local government finance, with lost income during the pandemic and additional reliance on reserves expected in 2022-23. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to explore whether greater flexibility can be afforded to councils to respond to local priorities and fund local services in the next budget round.

The Committee would welcome regular updates throughout the session on how the local government fiscal framework is progressing.

Implications of UK Government policy

Brexit implications

The Committee heard that the economic impact of Covid-19 may to some extent have masked the full impact of the UK withdrawal from the European Union, including in relation to the labour market, migration, and the supply of goods. This is an area we may wish to return to in the coming months. Here we focus on the impact of replacement EU funding.

Under the EU’s 2014-2020 Budget, Scotland was allocated up to €944 million in structural funding and, during this time, the Scottish Government played a key role in directing where funding in Scotland was spent. It also, under EU rules matched this funding from the Scottish Budget. Since leaving the EU, the UK Government has announced that it would:

at least match these EU funds “through the new UK Shared Prosperity Fund on average reaching around £1.5 billion a year” starting from April 2022;1

make available across the UK between March 2020 and March 2021, funding of £220 million in a Community Renewal Fund;

provide £4 billion for a “levelling up” fund for England with £800 million set aside for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.2

Local authorities are expected to bid for this funding directly to the UK Government, with the Scottish Government having no role in their distribution. The Cabinet Secretary highlighted challenges in the UK Government’s approach not applying COSLA’s methodology of ensuring “every local authority gets a fair share of the spend available”. She further argued that it was “extremely difficult to determine how to use our limited capital funding as far as we can for hospital projects, roads and schools when the UK Government is making decisions about capital spend that we are not sighted on”.3

The Cabinet Secretary further expressed concern that these replacement funds would not fully compensate for the loss of EU funding, particularly in areas such as the Highlands and Islands, nor had she received confirmation that the funding would be additional to the Scottish Government’s capital budget.4

The RSE recommended that these “new funding initiatives of the UK Government are distributed in cooperation with the Scottish Government and its development agencies, and where possible local authorities” to reduce the risk of “a lack of coherence as spending may become complex and duplicated”. It further suggested that the UK Government “should work with the Scottish Government and local authorities to ensure they are developed with coherence and are properly managed”, learning lessons from the experience of City Deals.5

The Committee has recently written to Scottish local authorities inviting them to comment on their experience to date in accessing funding available under the two current funds.6 We have also invited the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities to give evidence on the views we gather and on the UK Government’s plans for these replacement EU funds.7

As part of its Spending Review and Autumn Budget 2021 on 27 October 2021, the UK Government has announced £172 million in total for eight projects in Scotland from the first tranche of the Levelling Up Fund and £1.07 million for five projects under the Community Ownership Fund.8

The Committee looks forward to exploring evidence from Scottish local authorities on their experiences in relation to the UK Government’s replacement for EU funds and to hearing from the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities on this important matter.

In the meantime, we recognise, in line with other findings in this report, that greater communication and sharing of information between the UK and Scottish governments is needed to enable effective public spending in areas where there may be a shared interest.

UK-wide Health and Social Care Levy

The UK Government announced1 plans on 7 September to substantially increase funding for health and social care in England over the next three years, to be funded by a new Health and Social Care Levy. This will be based on National Insurance contributions until 2023 when the levy becomes a separate legislative entity. In a letter to devolved governments the same date, the Prime Minister announced that devolved administrations would benefit from Barnett consequentials from this spending on the NHS and social care in England, in the usual way. He further stated that “combining Barnett funding and UK-wide spending, by 2024-25, Scotland would benefit from an additional £1.1 billion”.2

The Cabinet Secretary indicated that “as things stand, it looks as though what will come through is a consequential funding increase that is related to spend in the Westminster budgets” and that further detail was expected in the upcoming UK Spending Review. She was unclear as to “whether that truly compensates” for the public sector in Scotland, as an employer, to pay for the increase in national insurance contributions.3

The Committee notes a lack of clarity as to whether the Scottish public sector will incur additional costs as a result of the proposed increase in employer national insurance contributions, under the UK Government’s Health and Social Care Levy. We invite the Scottish Government to provide an update on this issue and any consequences for the Scottish public finances following discussions with HM Treasury.