Finance and Constitution Committee

Pre-budget scrutiny report

Introduction

This pre-budget report is the first which the Finance and Constitution Committee (“the Committee”) has published following the recommendations of the Budget process Review Group (BPRG) and the Parliament’s agreement of a new budget process as set out in the Written Agreement between the Scottish Government and the Committee. The pre-budget report focuses on four documents:

Scotland’s Fiscal Outlook: The Scottish Government’s Five Year Financial Strategy1

Fiscal Framework Outturn Report2

Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts May 20183

Forecast Evaluation Report4

The first two documents are published annually by the Scottish Government following recommendations by the BPRG. The other two are published annually by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) on a statutory basis. The Committee welcomes the publication of all four documents as a comprehensive basis for its pre-budget scrutiny. In particular, the Committee welcomes the documents as integral to its scrutiny of the operation of the Fiscal Framework which forms the basis of its pre-budget scrutiny. This is the first year that the Committee has carried out this scrutiny and we intend to review our approach as part of our scrutiny of the 2019/20 Budget.

Overview

The Committee has previously emphasised that the Budget is now subject to a much greater degree of volatility and uncertainty. In particular, the Committee highlighted the risk to the public finances from forecast error in our report on Draft Budget 2018-19 which was published in January.1 This risk increases if there is a divergence in the extent of forecast error between the SFC and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The subsequent income tax forecasts by the OBR in March this year followed by the SFC forecasts in May illustrate the extent of this risk. The OBR revised its March income tax forecast for 2018-19 upward which resulted in a nominal increase in the BGA of £181m. The SFC revised its May forecast for income tax receipts in Scotland for 2018-19 downwards by £208m. While these revised forecasts have no direct impact on the size of the Scottish Budget they do give some indication of the potential impact of the divergence in forecasts. As an illustrative example they show that the net impact on the Scottish Budget would be a reduction of £389m. However, if the forecast were to turn out to be too optimistic and the SFC forecast too pessimistic there could be a net benefit to the size of the Scottish Budget.

The potential risk to the Budget from forecast error was then further highlighted in July following HMRC’s publication of outturn data for Scottish income tax for 2016-17. This is the first ever publication of outturn data for Scottish income tax and as the chair of the SFC pointed out to the Committee “represents something of a milestone in the devolution story.”2

The HMRC outturn data for 2016-17 show tax receipts of £10.7 billion compared with the SFC forecast in May 2018 of £11.3 billion. But it should be emphasised that the outturn figures do not have a direct impact on the budget as 2016/17 is the baseline year for both the BGA and Scottish income tax receipts. This means that the baseline for both the BGA and Scottish income tax receipts will now be revised downwards to £10.7 billion. The impact on the budget will depend on the relative growth of income tax receipts in Scotland and the rest of the UK from this baseline figure. If the relative growth is the same then there will be no impact. There is only an impact where there is divergence in the rate of growth.

While there may be no direct impact on the size of the budget there may nevertheless be an indirect impact arising from the fewer number of higher and additional rate taxpayers in Scotland than previously thought. The Committee’s Adviser points out that this “could mean that it is less likely that the growth of Scottish income tax revenues per capita will match the growth of rUK tax revenues per capita.”3

The Auditor General for Scotland (AGS) stated in written evidence to the Committee that understanding “the opportunities and risks inherent in the operation of the Fiscal Framework, and how these are being experienced and managed in practice, is critical to the effective oversight of the Scottish public finances.4” The Committee agrees and examines some of these risks and opportunities in the rest of this pre-budget report.

Economic Outlook

The SFC’s May forecast for GDP growth is broadly the same as it was in their last set of forecasts produced in December 2017 and is less than 1% per annum for each year of the forecast period. This is below the OBR’s forecast for GDP growth for the UK as is shown in table 1 below.

Table 1: GDP Growth Forecasts% growth 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 Scotland (SFC) 0.7 0.8 0.8 0.9 0.9 0.9 UK (OBR) 1.6 1.5 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5

The SFC forecast GDP growth of 0.7% for 2017-18 in May which was the same as its forecast in December 2017. Since then outturn figures have been published which show GDP growth of 1.3% in 2017-18 compared to 1.5% for the rest of the UK. The Committee’s Adviser explains that the “reason for the large discrepancy between the forecast and the outturn data is largely due to major revisions to the estimates of GDP growth published by the Scottish Government.” These revisions were a consequence of revisions to estimates of the timing of construction sector activity. Our Adviser points out that it is significant that while “the revisions to the GDP numbers changed the timing of GDP growth across years, the revisions did not have a material effect on the average GDP growth rate since 2010. The revisions therefore do not alter the SFC’s general judgement that the outlook is for relatively slower GDP growth in coming years.”1

The SFC state in their evaluation report that the revisions to GDP growth for 2017-18 “do not change the underlying picture of the Scottish economy as the upward revisions to growth in 2017-18 are more than offset by other revisions in earlier years. Overall, we do not anticipate that the revised GDP data will significantly alter our medium- to long-run view of the Scottish economy when it comes to our next forecasts.”2[1] The SFC explained to the Committee that “there is no evidence from this revision to suggest that we should change our underlying view of subdued trends in the economy.”3

The SFC was asked by the Committee if therefore the revised figures for 2017-18 amount to a blip. They responded that “all the indications are that we will still have a subdued long-run forecast.” The SFC also pointed out that the growth rates since 2010 “are marginally lower than they were before the revisions”4 and that the overall economic growth picture is just slightly below what it was in the forecast.”5

The SFC provide details in their evaluation report of the impact of this revision to the GDP growth figure on their income tax forecast for 2017-18. They state that “in isolation, our under-estimate of economic growth in 2017-18 has taken around £188 million off our income tax forecast for that year.”6 These figures are illustrative and have no direct impact on the Budget for 2017-18.

In our report on Draft Budget 2018/19, the Committee highlighted the risk to the public finances of lower economic growth in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK which may result in slower relative growth in the Scottish income tax revenues compared to income tax revenues in the rest of the UK At the same time we also recognised the potential benefits to the public finances from a higher relative rate of growth in the tax base in Scotland. The AGS highlights three aspects of risk in relation to economic performance –

The extent of structural and cyclical differences between the Scottish economy and the rest of the UK;

Underlying economic performances such as employment, wage levels, productivity, demand and government spending;

The point in the relative economic cycles of Scotland and the rest of the UK when the baselines for the adjustments to the block grant are established.

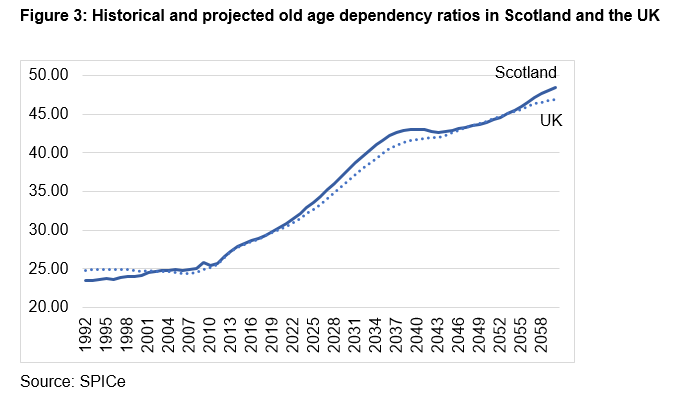

The Committee’s Fiscal Framework Adviser points out that many of these factors are not determined wholly – or in some cases even partially – by the Scottish Government. For example, wages and/or employment could grow relatively less quickly in Scotland as a result of structural change to the economy that was unrelated to policy. The ratio of the pension-aged to working-age population may also grow more quickly in Scotland which would be likely to reduce the growth rate of income tax revenues per capita in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK and this is discussed in more detail below.

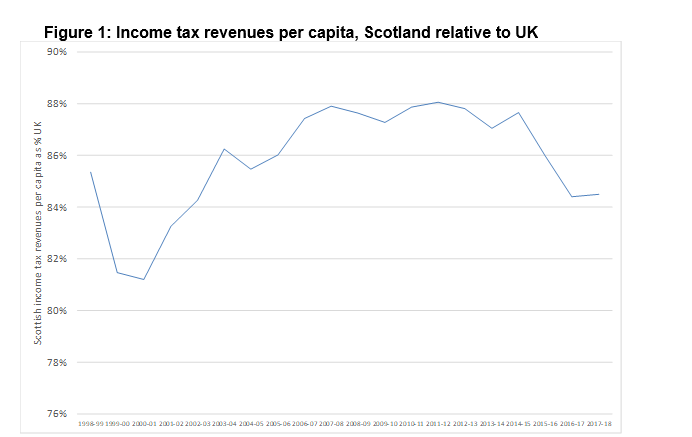

Our Adviser points out that between the early 2000s and 2015, employment and wages tended to grow somewhat more quickly (from a lower base) relative to the rest of the UK. This helped to drive faster growth in income tax revenues per capita in Scotland to the extent that the Scottish Budget would have been £800m per year better off by 2008 if income tax had been fully devolved in 1999. After 2008 a number of tax policy changes at UK level mitigated further increases in Scotland’s relative per capita income tax revenue growth even though wage growth remained relatively higher. Since 2015 there has been a fall in Scottish tax revenues per capita as a percentage of the UK. This is shown in Figure 1 below.

Fiscal Framework Adviser

The Scottish Government recognises in its fiscal outlook that the pace of economic (GDP) growth “is expected to remain below its historic trend.” 7The fiscal outlook also recognises that the “SFC’s latest forecasts continue to suggest that economic growth will be lower in Scotland than the UK as a whole over the next five years. This reflects their judgement that productivity growth will be weaker in Scotland than the OBR forecasts for the UK, as well as an expectation that the working age population will grow more slowly in Scotland.”7

The fiscal outlook recognises that while “the Scottish and UK economies have historically tended to follow similar paths, they do on occasion diverge. Recent data suggests that they are in a period of divergence at the moment across several areas, with GDP growth, earnings growth and employment growth currently weaker in Scotland.”9The Scottish Government states that it “is difficult to assess if and for how long this divergence will continue and to what extent it will impact on the Scottish Budget.”10 This is a view shared by our Fiscal Framework Adviser who states that the “extent to which a period of more prolonged divergence in economic performance might continue remains unclear.11”

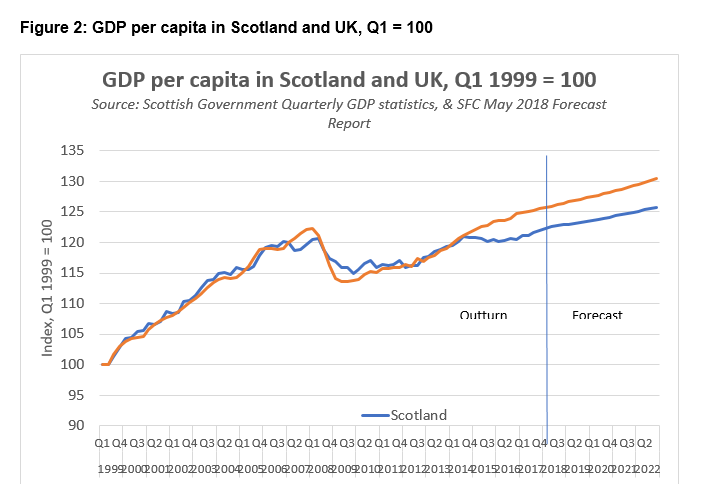

The Committee noted in our report on Draft Budget 2018-19 that “while per capita GDP growth in Scotland has largely tracked the UK since 1999 a gap has begun to appear over the past two and a half years.”12 The Committee concluded that while “it is not clear what the impact will be on income tax revenues there is nevertheless some risk to the public finances which will require close monitoring by both the Scottish Government and the SFC.”12

Our Fiscal Framework Adviser has provided a revised graph based on the most recent data and this is provided below in Figure 2.

Fiscal Framework Adviser

The AGS states in written evidence that where “differences in growth rates between Scotland and the rest of the UK continue over an extended period, the cumulative impact on future Scottish budgets is likely to be increasingly significant.” She highlights evidence from the Fraser of Allander Institute who have previously estimated that a “0.2% differential in wage growth rates would change budget revenues in the first year by £25 million, rising to around £130 million by the fourth year if this differential continued.”14 The FAI also suggest that the impact of this differential growth rate could become more significant once some VAT revenues are assigned to the Scottish Parliament.

The Committee welcomes the potential positive impact of the revised GDP growth figures for the Scottish economy in 2017-18 but notes that there remains a risk to the public finances arising from the SFC’s medium to long-run GDP growth forecast.

The Committee notes that the GDP growth forecast differential between Scotland and the rest of the UK is around 0.4 to 0.5% for each of the next four years. Based on previous FAI estimates of the impact of differential wage growth rates of 0.2% and as noted by the AGS this could have a significant impact on the size of the Scottish Budget. The Committee asks whether the Scottish Government and/or the UK Government has carried out any risk analysis of the potential impact of differential economic growth rates between Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Population Growth

As highlighted in our report on Draft Budget 2018/19 a key factor in explaining the OBR’s forecast for higher economic growth in the UK compared to the SFC’s lower forecast for economic growth in Scotland is population growth. The Scottish Government state in its Fiscal Outlook that “it is important to reflect on the key fact that population growth has been the most significant driver of GDP growth in both Scotland and the UK in recent years.” 1

The Committee heard further evidence as part of our pre-budget scrutiny that a further risk to the public finances in Scotland is the relative size of the working age populations in Scotland and the rest of the UK. The SFC explains that this is because–

The size of the population aged 16 to 64, which makes up most of the working-age population, is important for the economy and the public finances. These individuals are more likely to be working and will be generating the highest tax receipts, for example, in income tax.2

However, the annual adjustment to the block grant using the indexation per capita method is based on the overall population growth in Scotland and the rest of the UK. It does not account for the relative growth in the working age population or the ‘old-age dependency’ ratio which SPICe define as –

“the ratio between the number of people aged 65 and over (the age when people are generally ‘economically inactive’) and the number of people aged 16-64 (the so called ‘working age population’).”3

Figure 3 below shows the ONS based historical and projected old age dependency ratios in Scotland and the rest of the UK. It demonstrates that Scotland is forecast to have a higher dependency ratio than the rest of the UK for around the next 25 years.

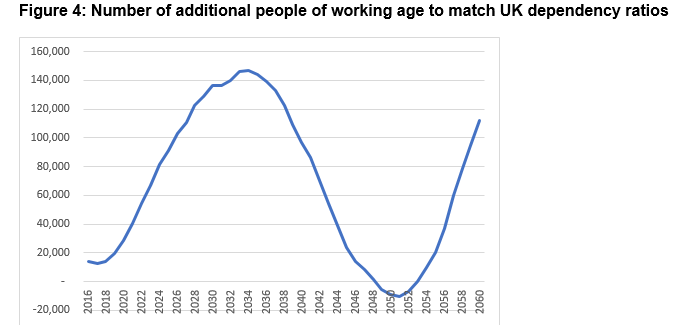

Figure 4 below shows how many additional 16-64 year old people of working age Scotland would need to match the dependency ratio projections of the UK. SPICe point out that this would peak at 147,000 in 2034” and that this “highlights the implications of the small differences in the dependency ratio.”

SPICe

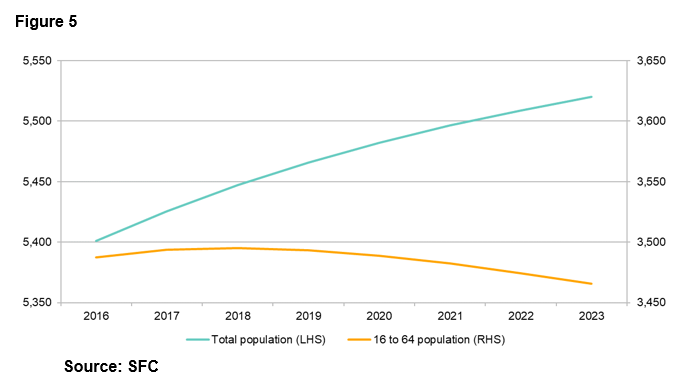

The SFC highlight the potential impact of population growth on economic growth in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK in their May forecast report. They point out that while the total population in Scotland is expected to grow in Scotland “the population aged 16 to 64 is expected to start to shrink from 2018 onwards. This is in contrast to a growing 16 to 64 population in the UK and places a particular drag on growth in GDP in Scotland.”4 This is shown in Figure 5 below.

Forecast Scottish total population and population aged 16 to 64, thousands

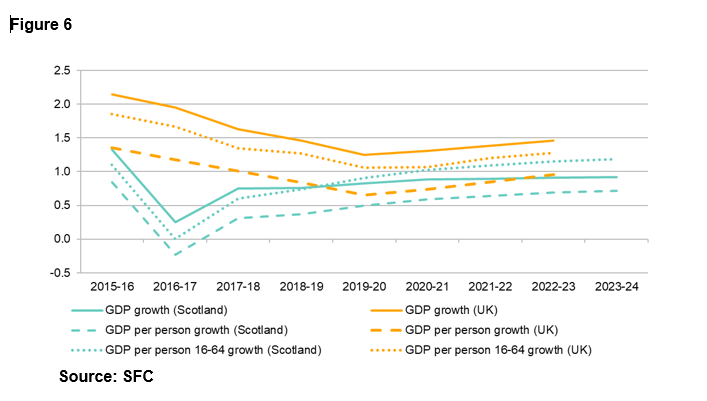

While the SFC are forecasting that Scottish GDP growth will be slower than UK GDP growth the gap is lower on a per capita basis. Indeed, as is shown in Figure 6 below the forecast GDP growth rate per person aged 16 to 64 is very similar in both Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Forecast growth in GDP and GDP per person, Scotland as forecast by the SFC and UK as forecast by the OBR

But because of the divergence between Scotland and the rest of the UK in the relative size of the working age population this creates a gap in the growth rate of GDP per capita. This is shown in the solid lines in Figure 4. As noted this is potentially significant for the size of the Scottish Government’s Budget given that the annual adjustment to the block grant is adjusted on the basis of general population growth rather than the working age growth.

The Scottish Government’s Fiscal Outlook states that while an ageing population is not new, it “is set to accelerate from 2021 onwards and is happening at a faster rate than in the rest of the UK.”5 The Scottish Government identifies two dimensions to this –

A big increase in the number of people aged 75 and over;

An ageing working population with fewer younger workers and more aged 50 and over.

The Fiscal Outlook states that the “challenge of an ageing population will continue at least for the next 25 years and over the longer term all future Scottish Governments will need to respond to the pressures this creates.”6

Dr Jim Cuthbert suggested to the Committee that the impact of population growth should be considered as part of the review of the Fiscal Framework and that “one possibility would be that, instead of the index per capita method of indexation, one could move to the index per working-age capita.” He also stated that “we should not shy away in that review from bringing in an assessment of needs at some stage".7

The Chief Secretary to the Treasury (CST) was asked by the Committee whether the review of the Fiscal Framework should include consideration of the impact of demographic change on the working age population in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK. She responded that “the Scottish Government is protected against risk with regard to population size relative to the tax take in both countries.”8 She also pointed out that “the Scottish Government has levers to influence demographics in Scotland, so I do not think that the issue of the shape of the population is entirely exogenous to Scotland.”8

The Committee notes that there is a strong evidence base that suggests there is a real risk to the size of the Scottish Budget arising from Scotland’s population ageing faster than the rest of the UK. In particular, there is a real risk from a higher growth in the old age dependency ratio in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK. This raises two fundamental questions –

Whether the Scottish Government has sufficient policy levers to address this risk;

Whether the Fiscal Framework sufficiently recognises demographic divergence?

The Committee recommends that it is essential that both of these fundamental questions are fully considered as part of the review of the Fiscal Framework.

Migration

The Fiscal Outlook states that international migration “has been the largest contributor to Scotland’s population growth over the past ten years, and to a greater extent than in any other part of the UK” and the “most recent population projections from National Records of Scotland indicate that all of Scotland’s population growth over the next 25 years is expected to come from migration (from both overseas and the rest of the UK).”1 The Scottish Government’s view is that this “provides a compelling economic case for why Scotland needs a tailored approach to migration, particularly in the context of an evolving devolution settlement where the Scottish Parliament now has significant new powers in relation to taxation.”2

The Scottish Government recently published a paper on migration policy, Scotland’s population needs and migration policy: Discussion paper on evidence, policy and powers for the Scottish Parliament. The paper states that “the case for new powers for the Scottish Parliament on migration is clear” and set out “options for a future migration system which would reflect Scotland’s needs.” 3

In evidence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary stated that “reducing immigration to the tens of thousands, as the Prime Minister has spoken about, would be singularly unhelpful to Scotland’s economy” and that the “UK’s one-size-fits-all policy is not appropriate.” 4 He went on to say that if “we collectively accept that there is a challenge to Scotland’s economy, surely it follows that we should have the appropriate levers to put us in a better position” and that “immigration is a case in point as to how the current system and current UK economic model just do not suit Scotland.” 5However, the CST to the Treasury told the Committee that the “Migration Advisory Committee’s report was very clear in not recommending a separate migration policy for Scotland. Indeed, that was confirmed by the director of the Confederation of British Industry, who suggested that such a move would not be helpful from the perspective of Scottish business.”6

CBI Scotland told the Committee that “Scotland and the north-east of England are the two areas of the UK that are projected to see a reduction in total available workforce by 2025. That means we need a UK immigration policy that is fit for purpose post-Brexit.”7 They stated that the businesses they had spoken to so far “have said that now is not the right time to devolve immigration powers and they would rather focus on getting the UK immigration system right in response to Brexit” but that “if it becomes a very restrictive system, flexibilities for Scotland will need to be addressed in some shape or form.”7

The Scottish Government’s Fiscal Outlook states that -

“The ‘Brexit’ effect of reduced migration could reduce Scotland’s GDP by 4.5 per cent per year by 2040 – equivalent to a fall of almost £5 billion a year. That is a more significant reduction than the rest of the UK will face, where real GDP could be 3.7 per cent lower by 2040 as a result of an EU exit-driven reduction in migration. The proportionately larger impact on Scotland is equivalent to £1.2 billion per year by 2040.”9

STUC Scotland told the Committee that “Brexit presents a significant challenge. From what the UK Government has said so far, it is clear that it will not necessarily maintain low-skilled immigration routes into the UK.”10 They point out that “EU workers, despite being very well qualified, are often doing quite low paid jobs. The median hourly pay for an EU worker was £8.60; for a UK worker it was £11.20; and for a non-EU worker it was £13.20.”10 This means “that we will need to think about how those roles are filled in the future if that immigration route is not there.”10

Jenny Stewart from KPMG pointed out that “we have seen the latest net migration figures and we know that far more EU nationals are already not coming to the UK.”13 She also stated that the “interesting piece about the latest Scottish data was that we were attracting more people from elsewhere in the UK to Scotland” and that “it would be worth considering a focus on how we can attract more people from the rest of the UK into Scotland.” 13

The SFC state in their May forecasts report that they “must make assumptions about the impact of Brexit on Scotland” but “the outcome of the negotiations remains unclear, and it is therefore difficult to forecast the impact on the economy.”15 At the same time, the SFC “broadly expects both the uncertainty created by the UK-EU negotiation and the final settlement to impact negatively on the Scottish economy over the next five years.” The SFC have used the same broad-brush assumptions as the OBR as follows –

The UK leaves the EU in March 2019;

New trading arrangements with the EU and others slows the pace of import and export growth;

The UK adopts a tighter immigration regime than currently in place.

Based on these assumptions, the SFC forecasts the following impact on the Scottish economy –

Impact on migration – projected lower EU migration than in the principal projection;

Impact on productivity – slow growth in productivity, in part due to UK-EU exit;

Impact on trade – slower growth in Scottish international trade.

In relation to the projected lower EU migration the SFC explained to the Committee that “instead of a net in-migration of 15,000 per annum, there will be a net in-migration of 9,000 per annum.”16

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether he believes that “there is enough flexibility within the fiscal framework to contend with the particular shocks and damaging effects that a hard Brexit could have on Scotland.” He responded that “I don’t think that the fiscal framework agreement envisaged these circumstances and therefore I do not think that there is enough flexibility to deal with such a shock” although “the shock could be to the whole of the UK; it might have a disproportionate impact on Scotland.”17

The CST to the Treasury was asked by the Committee whether she is “entirely confident that, whatever eventualities come from the Brexit negotiations, the overall flexibility that exists within the fiscal framework will meet the requirements of the Scottish Government. You have no concerns at all regarding flexibility.” She responded that “is right.”18

The Committee notes the recommendation of the Smith Commission that the Scottish and UK Governments should work together “to explore the possibility of introducing formal schemes to allow international higher education students graduating from Scottish further and higher education institutions to remain in Scotland and contribute to economic activity for a defined period of time.”19 The Committee also notes that this recommendation has not yet been implemented.

The Committee notes that given the way in which the Fiscal Framework operates there is a real risk to the size of the Scottish Budget if there is a fall in Scotland’s working age population due to a disproportionate decline in immigration relative to the rest of the UK. The Committee recognises that migration policy is a reserved matter and that the UK Government does not agree with the need for a specific migration policy for Scotland. However, within the context of Brexit and a different demographic dynamic within Scotland relative to the rest of the UK, the Committee recommends that the review of the Fiscal Framework should fully consider the impact of immigration policy following the UK’s departure from the EU.

EU Funding

The Fiscal Outlook states that EU funding “is very important to a wide range of sectors and its loss following the UK’s exit from the EU could create pressures on Scotland’s public finances” and the “current EU funding round (2014-2020) is expected to benefit Scotland by over £5 billion.”1 The Fiscal Outlook also states that the lack of details from the UK Government about successor arrangements “continues to create significant uncertainty for those who rely heavily on this investment.”2

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that we “need longer-term certainty about EU funding” and that “as a minimum, we should continue to get the full benefit of the resources that we got from being part of the European Union."3

The Committee recommends that there needs to be much greater transparency and consultation with the devolved institutions in developing and agreeing the successor arrangements for EU funding post-Brexit.

Revisions of Forecasts for Income Tax

Table 2 below shows the comparison between the SFC’s February forecast for Scottish income tax and its May forecast.

| £ million | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February | 11,214 | 11,584 | 12,177 | 12,647 | 13,152 | 13,733 | 14,372 | |

| May | 11,267 | 11,467 | 11,969 | 12,345 | 12,805 | 13,335 | 13,936 | 14,547 |

| Change | 53 | -118 | -209 | -302 | -347 | -398 | -437 |

Table 3 below shows the comparison between the OBR’s forecast for the Block Grant Adjustment figures for income tax in November 2017 and March 2018.

Table 3. OBR Block Grant Adjustment Forecasts£ million 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 November 11,214 11,523 11,749 12,056 12,477 12,936 13,403 March 11,267 11,626 11,930 12,215 12,612 13,015 13,531 Change 53 103 181 159 135 79 128

These revised forecasts do not have any immediate impact on the size of the Scottish Government’s Budget. However, they do provide a useful indication of the potential risk to the public finances if these revised forecasts turn out to be closer to the outturn figures than the previous forecasts. Our Fiscal Framework Adviser explains “they provide an early sense of the extent to which the December 2017 forecasts might be revised, and in which direction.” The Scottish Government point out in their Fiscal Outlook that while the forecasts provide a direction of travel, “significant uncertainties remain, as experience shows that forecasts are subject to considerable change between fiscal events.” 1

The Fiscal Outlook also emphasises the additional uncertainty arising from different sets of forecasts being produced by the OBR and the SFC on the basis that “there are many factors that may contribute to differences in these forecasts.”2 For example, the forecasts are produced “at different times using different methodologies, assumptions and input data’s.”2

The potential impact on the budget is calculated by subtracting the OBR’s forecast for the Block Grant Adjustment from the SFC’s forecast for revenue receipts. For example, the figures for 2018-19 are shown in Table 4. This shows that the net effect of the forecast revisions by both the OBR and the SFC would reduce the Scottish Government’s Budget by £389m if they turn out to be more accurate than the previous forecasts.

Table 4. Income Tax Forecasts 2018/19£m Autumn 2017 Spring 2018 Revenue Forecast 12,177 11,969 BGA Forecast 11,749 11,930 Net Difference 428 39

The Committee also notes that the SFC’s income tax revenue forecast in May includes an additional £213m arising from the Scottish Government’s changes to income tax rates and bands in the Budget for 2018-19. Without this additional revenue the adjustment to the block grant would be higher than income tax revenues according to the latest forecasts.

The Committee has sought to get a better understanding of why the SFC has revised down its forecasts for income tax between February and May. Our Fiscal Framework Adviser explains that the forecasts have been revised down due to a substantial revision of the SFC’s forecasts for nominal and real wage growth in each year of the forecast period.

The Committee had previously asked the SFC in our report on Draft Budget 2018/19 why “its judgements about earnings growth do not appear to be influenced by its growth and productivity assumptions.” The SFC responded that while an important driver of real earnings growth is productivity, “there are a number of other factors that will influence growth in real wages, particularly in the short term. These are inflation, growth in employment and unemployment, broader demand conditions in the economy and demographics.” 4

The Committee’s Adviser points out that in its May forecasts the SFC has not materially changed its assumptions about these factors and that the revisions to its wages forecast reflect an “evolution of judgment.” His view is that this is to be expected in forecasting the uncertain relationships between economic variables but “to have had such a significant evolution of judgement over a relatively short period can create substantial budgeting issues.”5

The SFC was questioned by the Committee as to why its wages forecast had changed significantly over a four month period. The SFC responded that they have “looked further at real wage growth” and that the “overall picture over the past 10 years is one of very low wage growth, and we have taken that more fully into account in this forecast than we have done previously.”6 The SFC also explained that “real wages now are lower than they were in 2009. That is a virtually unprecedented economic picture. We should focus on the story that real wages have not increased for 10 years” and that “the long-run story about real wages is the most important thing to focus on.”7

Dr Cuthbert suggests that there is “quite a strong potential anomaly” in that the SFC forecast a higher rate of growth for income tax receipts in Scotland than the OBR forecasts for the rest of the UK “even though “it forecasts that per capita gross domestic product and average earnings will grow at a slower rate in Scotland than in the rest of the UK.8 He proposes that “there needs to be a mechanism that identifies anomalies like that and then digs into the figures.” 8

The Cabinet Secretary was asked for his view on the changes to the SFC’s income tax forecasts between December and May. He responded that “I was as surprised as the Committee that there is such a difference between the December forecasts and what we see now” and that it “is curious that the analysis of the impact on wage earnings, which is a key issue, was not fully explained by the SFC".10 He questioned why the SFC forecast for wage growth changed when its GDP growth figure remained broadly the same.

The Cabinet Secretary also highlighted the different forecast methodologies and assumptions used by the OBR and the SFC. He told the Committee that the while the “OBR has taken a top-down approach to the Scottish economy; the SFC…has taken a bottom-up component approach to the Scottish economy”11 and that “the gap between the forecasts increases the volatility that we are dealing with.”12 Given this level of volatility he suggested to the Committee that the Scottish Government “need more levers in addition to the borrowing powers and having a reserve.”13

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee what risk analysis the Scottish Government had carried out in relation to the potential impact of the operation of the Fiscal Framework on the public finances including the volatility arising from forecast error. He responded that while some analysis informed the fiscal outlook document the Scottish Government “can take further analysis” and present that to the Committee and the UK Government “well in advance of 2021.”13

The Committee notes that the extent of the revisions to both the SFC and OBR forecasts over a relatively short period of time highlights the extent of the potential volatility arising from the operation of the Fiscal Framework. While there is not yet sufficient outturn data to support specific changes to how the Fiscal Framework operates there is nevertheless an emerging pattern of a high degree of volatility which should be addressed as part of the review. The Committee welcomes the commitment by the Cabinet Secretary to carry out further risk analysis to support that review.

Forecast Error

In our report on Draft Budget 2018/19 the Committee emphasised that “there is a risk to the public finances if there is significant forecast error .”1 The AGS highlighted a number of risks inherent in forecasting tax revenues in a written submission to the Committee as follows –

The extent of underlying uncertainty about the economy;

The availability of relevant and robust data;

The robustness of the OBR and SFC’s respective methodologies and judgements;

Differences in methodologies and judgements between the SFC and OBR;

Forecast horizons.

The AGS points out that in “a period of significant economic uncertainty, forecasting is inherently more challenging and forecasting risk increases.” 2

The Committee notes that HMRC’s publication of outturn data for 2016/17 is the first opportunity to consider the scale of forecast error in relation to income tax. While the Committee recognises that the forecast error for 2016/17 has no direct impact on the Budget it provides some useful evidence of how the Fiscal Framework is working. The SFC’s income tax forecast for 2016/17 published in May 2018 was £11.267 billion. The OBR Scottish income tax forecast for 2016/17 published in March 2018 was £11.415 billion. The HMRC outturn figure published in July 2018 was £10.72 billion. This means that the SFC’s forecast error for 2016-17 was £550m while the OBR forecast error for 2016-17 was around £700m.

The SFC state in their evaluation report published in September that they “believe most of this headline error of £550 million is because of data issues.”3 The most significant issue with the data was the difference between the number of higher and additional tax payers in the outturn figures for 2016-17 compared with the SPI data for 2015-16. The SFC’s forecast evaluation report states that the May forecast figure for 2016-17 was based on SPI data and assumed there were 15,500 additional rate taxpayers and 308,500 higher rate taxpayers. The outturn data for 2016-17 shows that there were in fact 13,300 additional rate and 294,000 higher rate taxpayers. See Table 5.

Table 5. Number of Income Taxpayers, 2016/17Higher Rate Additional Rate SFC May Forecast 308,500 15,500 HMRC Outturn Figure 294,000 13,300

This means that the forecast error for the number of higher rate taxpayers was 4.7% while the forecast error for the number of additional rate taxpayers was 14.4%. The SFC explain that “our error in forecasting the number of taxpayers could have affected our forecast of liabilities by around £500 million holding all else constant.” Given the very high tax liabilities of the additional rate taxpayers the reduced revenue from having 2,200 fewer is estimated to be £263m. The estimate from having 14,500 fewer higher rate taxpayers is £211m.

Tables 6 and 7 below shows the SFC’s December forecast for the number of additional and higher rate taxpayers in Scotland.

Table 6. Forecast Number of Additional Rate Taxpayers2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 December Forecast 18,900 20,300 21,800 23,500 25,300 May Forecast 17,100 18,000 19,200 20,800 22,800 Table 7. Forecast Number of Higher Rate Taxpayers2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 December Forecast 332,000 337,100 348,200 360,300 374,300 May Forecast 338,400 340,300 350,400 362,200 374,300

This shows a significant fall in the number of additional rate taxpayers between the December forecast and the May forecast across the forecast period and a small increase in the number of higher rate taxpayers. The SFC were asked by the Committee how the change in the number of additional and higher rate tax payers in Scotland would impact on future forecasts. They responded that “we will be rebasing the forecasts and the number of taxpayers using the outturn data for 2016-17, which should give us a far better and more accurate forecast.”4

The CST was asked by the Committee whether there was enough flexibility within the Fiscal Framework to deal with the impact of forecast error. She responded that “the whole purpose of the work of the Smith commission was that more revenue risk be held by the Scottish Government in exactly the same way as what happens if we have a forecast from the OBR at a UK budget that does not bring in the tax revenues that we expected and we have to adjust our budget accordingly.”5

HMRC Data

HMRC is required under its Service Level Agreement (SLA) with the Scottish Government to –

Provide the Scottish Government with sufficient relevant and timely information and data for rate-setting and forecasting for Scottish income tax;

Provide the Scottish Government with sufficient relevant and timely information and data to discharge its duties in respect of cash management due to any change between forecast and collected amounts of Scottish income tax.

Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI)

The data set used by HMRC to provide the Scottish Government with the information it needs for rate-setting and forecasting of Scottish income tax is the SPI. This information is also provided to the Scottish Fiscal Commission. The SPI is based on information held by HMRC on individuals who could be liable to UK tax and is carried out annually by HMRC. The survey covers income assessable to tax for each tax year. HMRC provides the Scottish Government with an annually updated copy of the SPI data set which is the same as that provided at a UK level with some minor adjustments to avoid potential breaches of taxpayer confidentiality.

The SFC explain that they forecast Scottish income tax liabilities using the publicly available version of the SPI as, at the time, “this was the best available source of information on income tax liabilities for Scotland”1 but that they are now “in the process of developing a methodology to align our forecasts with the outturn data” 2 Given the availability of this outturn data “they do not expect errors of this scale to be commonplace in our future forecasts of income tax.”3

The Committee’s Adviser points out that “it was always assumed that the SPI would provide a relatively robust estimate of Scottish income tax revenues in previous years” but that it “now appears that the SPI is less closely aligned to outturn income tax than had been assumed.” He suggests that this “has implications for how the SFC uses the SPI to forecast outturn revenues in future.”4

The SFC highlight in their statement of data needs that it is “essential that our income tax forecast is based on data of comparable quality and timeliness to the data used in the OBR’s UK forecasts.”5 However, HMRC state in their annual report on Scottish income tax for 2018 that although “the SPI is considered representative of the UK taxpayer population, it is less reliable at a sub-UK level.” The SFC state in their evaluation report published in September 2018 that while the SPI “may do a good job of estimating the overall shape of the income distribution in Scotland, it appears to be overestimating the number of taxpayers relative to outturn data. This is particularly the case at the top end of the distribution for the highest income taxpayers.”6

The SFC identify a number of priorities for improving income tax data in their statement of data needs published in September 2018 as follows –

HMRC to provide Scotland-specific composite records in the PUTi

HMRC to develop an Official Statistics publication of Scottish outturn income tax liabilities;

HMRC to develop an Official Statistics publication of the PAYE RTI liabilities.7

The SFC indicate that “HMRC have stated that they are willing to constructively and collaboratively engage with SFC on the above priorities.”8

Outturn Data

HMRC collects PAYE income tax revenues on a monthly basis. HMRC has recently been making some of the PAYE information publicly available at the level of UK regions and countries in ‘real time’. In practice, this means that in July 2018, HMRC published its second experimental quarterly Real Time Information (RTI) publication which contains the number of individuals receiving pay from PAYE, their mean and median pay as calculated from that source, and the total amount of pay from PAYE in each country or region of the UK. The public data does not include estimates of PAYE income tax receipts or liabilities. The latest available data is for the final quarter of the 2017/18 financial year (i.e. Jan- Mar 2018).

In addition to this published information, HMRC also use the PAYE RTI system to provide the SFC and Scottish Government with monthly data on PAYE income tax receipts. It is anticipated that this data will be made available publicly once its robustness has been sufficiently tested.

The SFC state in their May forecast report that “HMRC have been developing more timely estimates of Scottish income tax liabilities than currently available from the SPI”1 and that they have been providing the SFC with “provisional RTIi tax receipt estimates, covering April 2016 to March 2018.”1 However, while the SFC believe that this data provides a potentially valuable source of RTI they also view it as having some drawbacks including only covering PAYE and therefore they “make no direct adjustments to our forecast using the RTI data.”3

The SFC explain that their income tax “forecasts are based on the 2015-16 SPI, and are projected forward using Scottish specific economic determinants which we produce as part of our economy forecasts.” As noted above they do not use any of the available RTI outturn data in preparing their forecasts. This is a different approach from the OBR whose “UK income tax forecast is partly adjusted based on the available 2016-17 and 2017-18 outturn receipts data for the UK.” 4

The Committee asked HMRC about the provision of outturn data for Scottish income tax liabilities as part of our scrutiny of Draft Budget 2018/19. They responded that they “now have an arrangement with the Scottish Government to provide the monthly data for Scottish taxpayers” and that these “figures are being looked at by HMRC and the Scottish Government each month as they come through.” HMRC also explained that they “hope to publish that series in the future, but we want to get a bit of experience of the figures and make sure that we understand them before we make them a public document.”

The Committee asked the Scottish Government in our report on Draft Budget 2018/19 whether it agrees that monthly outturn data for Scottish income tax is made publicly available as soon as practicable to do so. The Scottish Government responded that regular “publication of outturn data is required under the Service Level Agreement and the Scottish Government is working with HMRC to ensure timeous compliance.”5

The Committee recognises that forecast error is inevitable and that, therefore, the SFC and the OBR have a very challenging role in preparing independent forecasts which have a direct impact on the size of the Scottish Budget. At the same time the Committee is keen to ensure that there is a sufficient focus on ensuring that the impact of forecast error on the size of the Scottish Budget is minimised. The Committee would therefore welcome further clarity from both the SFC and the OBR on the following issues:

The extent of the difference between their respective methodologies and assumptions and how much of a factor is this in explaining differences between their forecasts;

Whether the HMRC data the SFC use is broadly of comparable quality and timeliness to the data used in the OBR’s UK forecasts and if not where are the gaps;

Why does the OBR use the available income tax outturn receipts for 2016-17 and 2017-18 in preparing its income tax forecast and the SFC does not;

What is the likely extent of the impact of this different approach to the use of outturn data on the respective OBR and SFC income tax forecasts;

What are the implications of the difference between the SPI data for 2016-17 and the HMRC outturn data for how both the OBR and the SFC use the SPI data in preparing future income tax forecasts.

Reconciliation Process

A further risk for the Scottish Government in managing the size of the Scottish Budget is the lag between budget allocation based on forecast income tax receipts and the reconciliation process based on outturn figures. HMRC’s audited outturn figures for income tax are not normally available until 15 months after the financial year. For example, the outturn figures for 2018/19 will not be available until July 2020. Furthermore, any forecast error will not impact on the Scottish Government’s Budget until 2021/22. The Committee considered that when more robust RTI on Scottish income tax receipts becomes available whether there is scope to have a provisional reconciliation process in advance of the final reconciliation between the forecasts and outturn figures.

The Committee asked HMRC whether they would be able to provide sufficient data to support a provisional reconciliation process. HMRC explained that while, as noted above they are developing RTI there are three issues with that –

it does not include self-employed income, which is about 16 or 17 per cent of the income tax receipts;

with our pay-as-you-earn codes, we sometimes adjust for things that are not relevant to Scottish income tax so the amount of tax that is being deducted through PAYE is not always precisely the same as what the Scottish income tax outturn will be;

the information is based on the S code each month. However, the test for being a Scottish taxpayer is an annual test rather than a monthly test.

The Committee’s view is that careful consideration should be given to the possibility of a provisional reconciliation process but that should be dependent on detailed consideration of:

the robustness of RTI data in comparison with outturn figures; and

the extent of forecast error and the impact on the size of the Scottish Budget.

The Committee recommends that this consideration should form part of the review of the Fiscal Framework.

Capital Borrowing

The Scotland Act 2016 provides the Scottish Government with capital borrowing powers of up to £450 million annually with an overall cap of £3 billion. These capital borrowing limits came into effect for the Scottish Government on 1 April 2017. The Fiscal Framework Outturn Report states that in total, “the Scottish Government will have accumulated £1,459 million of capital debt by the end of 2018-19, well within it overall £3 billion limit.”1 The Fiscal Outlook states that the “2018-19 Scottish Budget plans to make full use of the £450 million capital borrowing powers available to maximise infrastructure investment and economic impact.”2

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether the Scottish Government intends to continue to draw down their £450m borrowing limit each year which would mean reaching the overall £3 billion limit by 2022. He responded that “in the medium-term financial strategy I have not set out the longer-term capital plans” but if there is a UK “comprehensive spending review in spring next year, that might give us the ability to set out further multiyear budgets in terms of capital.”3

The Cabinet Secretary was also asked whether he anticipated asking the UK Government to raise the overall capital borrowing cap above £3 billion. He responded that it is a premature question but that he would always, as would any Finance Secretary, want as much flexibility as possible.4

The Committee would welcome an indication in the 2019/20 Budget as to whether the December forecasts for the Scottish economy mean that the Scottish Government is more or less likely to use its full capital borrowing power over the forecast period.

Air Departure Tax

Air Departure Tax (ADT) was devolved by the Scotland Act 2016, and the Scottish Government introduced the Air Departure Tax (Scotland) Bill in December 2016 to make provision for ADT to be charged on the carriage of chargeable passengers on chargeable aircraft by air from airports in Scotland.

The Finance and Constitution Committee was lead committee on scrutiny of the Bill which received Royal Assent in July 2017 with the introduction of this tax planned for April 2018. An exemption from Air Passenger Duty (APD) for flights from the Highlands and Islands (H&I) has been in place since 2001 and transferring the exemption to the new ADT requires notification to and assessment by the European Commission under State Aid rules, in compliance with EU law.

The UK and the Scottish Government decided to delay the introduction of ADT because discussions about a possible tax exemption for flights from H&I airports had not been resolved.

The Committee has been kept updated on the expected introduction of ADT in Scotland and in June 2018, the Cabinet Secretary wrote to the Committee outlining his intention to to defer the introduction of ADT beyond April 2019. He explained the reason being-

“Firstly, I understand that industry stakeholders need clarity to enable them to plan for ticket sales and route development. A further factor is my understanding of Revenue Scotland’s need for sufficient notice to restart the ADT programme and become operationally ready to collect the tax. The final factor is the ongoing uncertainty concerning State Aid rules (and hence the Highlands and Islands (H&I) exemption) following Brexit. “1

The letter stated that he continued to work with the UK Government on a solution to this issue and that, in the meantime, the current APD rates and bands will apply in Scotland from 2019-20 and the current UK APD H&I exemption will also still apply, until such time as the Scottish Government and UK Government agree to resume the transition from APD to ADT.

In June 2018 during evidence on the Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy, the Cabinet Secretary was asked about this letter and when he thought that ADT would be introduced. He replied—

“I will not switch on the tax in Scotland with defective devolution and before the issue is resolved. I will not impose the tax for the first time in the Highlands and Islands and I want a like-for-like exemption. I am working constructively with the UK Government to find a resolution, and I continue to engage with airports, airlines and other stakeholders in relation to aviation policy in Scotland.” 2

During our pre-budget 2019-20 scrutiny, the Committee questioned the CST on this issue to which she told us —

“The issue with regard to the Scottish Government exiting existing APD arrangements and establishing a new tax is the potential for a Highlands and Islands exemption not to meet state-aid requirements. Part of the EU deal that we have put on the table is that we want to continue to be part of a state-aid regime, because we think it very important for competition policy that the UK has a robust regime in that respect. We are working with the Scottish Government on the matter. We have offered to help by approaching the European Union, but I do not believe that we have been asked to do so on the Scottish Government’s behalf.”3

Following this evidence session, the Cabinet Secretary wrote again to the Committee stating that there had been a series of meetings and correspondence with the UK Government and—

“As part of this engagement, I have previously written to the Financial Secretary to the Treasury (FST), explicitly asking the UK Government to notify on the Scottish Government’s behalf. The Treasury have said they will only notify if the Scottish Government signs up to take on the full liability for all risks, both historical and future, including the potential for knock-on effects on Highlands and Islands business. These conditions are clearly unacceptable and not something I can agree to. “4

When giving evidence on our pre-budget 2019-20 scrutiny, the Cabinet Secretary reiterated the current position. He told us that Mel Stride MP, who at the time was Financial Secretary to the Treasury, wrote to him in July saying—

“In our conversation you expressed your wish to notify the European Commission formally for a Highlands and Islands exemption for your new ADT. I want to reiterate the serious concern I expressed in our call about this approach.5

He went on to explain that the UK Government had reservations about notification to the European Union as it did not think that the proposal was compliant with EU rules, and had suggested that if the Scottish Government were to take on the liability it might approach Europe. He stated again that this was not something the Scottish Government wished to do.

He also said that he had set up a Highlands and Islands working group so that all interests can come together to see whether there are other ways forward, recognising the need to address the Highlands and Islands exemption.

The Committee appreciates the difficulties surrounding the introduction of ADT in Scotland and understands why the UK and Scottish Governments have agreed to defer its introduction. However, the Committee believes it is imperative that both Governments continue to work together more closely to develop options for devolving ADT and delivering an exemption for Highlands and Islands passengers at the earliest opportunity. In addition, the Committee requests that the Scottish Government provides further information on the Highlands and Islands working group and continues to keep the Committee and the Parliament updated on this issue.

Value Added Tax (VAT)

The Scotland Act 2016 provided for the first 10 pence of the Standard Rate of Value Added Tax (VAT), and the first 2.5 pence of the Reduced Rate, to be assigned to the Scottish Government. The assignment of VAT will be based on a methodology that will estimate expenditure in Scotland on goods and services that are liable for VAT.

The Fiscal Framework set out that VAT assignment will be implemented in 2019-20. There will be a one-year transitional period during which VAT assignment will be forecast and calculated, but with no impact on the Scottish Government’s budget. From 2020-21 the Scottish Government’s budget will in part be determined by forecast and final estimated VAT receipts in Scotland.

In its Sixth Annual Report on the Implementation and Operation of the Scotland Act 2012 and Second Annual Report on the implementation of the Scotland Act 20161, the UK Government said—

“VAT rates will continue to be set at a UK-wide level. The UK and Scottish Governments have agreed that VAT assignment will commence in 2020-21, following a one year transition period to test the assignment methodology. HMRC’s Scottish Tax Devolution Programme Board will directly oversee the transition of these other tax powers. “

On the 5 September 2018, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) published a paper entitled Value Added Tax (VAT) Approach for Forecasting, outlining its proposed approach to forecasting the VAT revenue due to be assigned to Scotland from 2019-20.2 In this paper, the SFC said that now that their remit has been expanded to include VAT forecasting 3, it intends to produce its first full VAT forecast in the Economic and Fiscal Forecasts publication, which will accompany the 2019-20 Scottish budget. The paper stated—

“There has so far been no detail published on the model that will estimate the VAT assigned to Scotland and be the baseline for our forecast. It is expected that an overview will be published in the next month with fuller details to follow in 2019. We believe that, for the transparency and good governance of VAT assignment to Scotland, it is essential that full details of the assignment model are published. “

During our evidence session on 27 September, the Committee asked for an update on the methodology being used to estimate VAT assignment and how robust it was. The CST said the UK Government had been working with the Scottish Government on the methodology. She told us —

“We will shortly be publishing the proposed methodology. It is essentially based on the work that we already do when we report the VAT gap to the European Union, for example, so it is a robust methodology. It is also used internationally. The way that value-added tax is divvied up between the Canadian provinces is another example of this methodology being used, so we think that it is a very robust methodology that is used extensively internationally.”4

Lindsey Whyte explained further—

“The assignment model looks at expenditure in Scotland compared with the UK and it then works out an attributed VAT share for Scotland. We have to do that because businesses do not currently have to disaggregate their VAT returns by geographic area. We are using independent expenditure data from the Office for National Statistics and both Governments have agreed to commission an enhanced survey from the ONS to improve the data, which will be available through the implementation period. 5—

Lindsey Whyte also confirmed that in the autumn budget, the OBR will produce a forecast for rest of UK VAT, and shortly afterwards, the SFC will forecast Scottish VAT receipts using this new methodology for the Scottish budget to inform the implementation year.

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary whether he was concerned that the assignment of VAT to Scotland will be based on a statistical model rather than actual outturn VAT receipt data. He said that he had raised concerns with the CST told us6

“I know the committee has expressed concern about going, essentially, from estimate to estimate on VAT, for which we never get an outturn figure, unlike income tax or other devolved taxes. That is quite challenging and could be quite volatile. I continue to have concerns about that.”

The Committee is concerned that basing VAT assignments for Scotland on estimated figures could potentially introduce further volatility into Scotland’s public finances. The Committee recommends that both Governments should continue to review the methodology used for assigning VAT to Scotland during the implementation year to ensure its robustness and reduce the level of risk from forecast error.

The Committee requests that the Scottish Government provides regular updates on the development of the methodology used for VAT assignment to Scotland and the independent Scottish expenditure data and expects to return to this issue in the coming months.

Conclusion

The Committee has previously emphasised the potential volatility and uncertainty which may arise from the operation of the Fiscal Framework. This pre-budget report highlights two key issues which require close monitoring and risk management. First, there are risks arising from forecast revisions especially where there is a divergence in these revisions between the OBR and the SFC. While these revisions may not have any immediate impact on the size of the Budget they may have an impact on the size of future budgets and this needs to be closely monitored. Second, there are risks arising from forecast error in relation to outturn figures. The divergence between HMRC’s outturn figures for 2016/17 and the SFC and OBR forecasts do not have a direct impact on the Scottish Government’s budget. But they do illustrate the extent of the potential risk to the Scottish Government’s management of the public finances. This risk is exacerbated by the length of the lag between the budget allocation and the reconciliation of forecasts with outturn figures. Again, this requires to be closely monitored and the risk needs to be effectively managed.

The Committee has also previously emphasised the risks and opportunities arising from the increased powers which the Scottish Government can use to both grow the Scottish economy and to generate increased tax revenues. At the same time the Committee also recognises that other powers are reserved to Westminster and that Brexit introduces a great deal of uncertainty which was not anticipated when the Scotland Act 2016 was passed. The Committee notes that despite the increase in Scotland’s GDP growth figures for 2017-18 that the SFC’s medium term forecast remains more pessimistic than the OBR forecast for the UK economy. This presents a potential risk to the public finances and the Committee recommends that this risk needs to be carefully monitored. This will require improvements in the level and quality of outturn data which is publicly available including the publication of monthly data for income tax receipts In Scotland. The Committee recommends that this should be addressed as a matter of priority.