Education and Skills Committee

What support works? Inquiry into attainment and achievement of school children experiencing poverty

Introduction

The Education and Skills Committee ("the Committee") undertook an inquiry into the impact of poverty on attainment and achievement of school-aged children and young people. This work is in the context of reports that poverty is an increasing problem for families in Scotland. The Committee was interested in finding out about the ways poverty impacts on children in school education and the ways in which our schools and other services mitigate this impact.

How we took evidence on this inquiry

In all its work, the Committee is keen to ensure that it hears from a wide range of people and organisations. This inquiry was no different and the Committee heard from; young people, parents, teachers and school staff, Community Learning and Development ("CLD") professionals, a wide range of individuals working and volunteering in the third sector, representative organisations, and local and national government.

The Committee took evidence in a number of different ways. The Committee sought written views from a number of stakeholders at the outset of its inquiry and also issued an open call for views from young people, parents/carers, school staff (including teachers), and other professionals who work in our communities.

In the open call for views, the Committee asked about people's and organisations' experience of what support is available to children and young people experiencing poverty, what has worked well, the impact of this support, any barriers to success and what else could be done to help. The Committee agreed that individuals' responses could be published anonymously if requested.

The Committee received a high number of responses. A list of the responders are included the Annexe to this report and all of the submissions are published and available online.

The Committee took formal evidence at the Scottish Parliament over five meetings in April and May 2018. More details of the formal evidence sessions are included in the Annexe.

In addition, the Committee arranged a number of informal meetings and events to hear directly from people on the front line. On the mornings of 25 April, 2 May and 9 May, the Committee held breakfast meetings with parents, young people, front-line staff and volunteers mainly from the organisations who gave evidence. Members of the Committee also held a discussion group with a number of CLD professionals on Monday 30 April 2018.

Members of the Committee visited Queen Anne High School, Dunfermline, on 1 May. During the visit, the Committee also met with staff from St Serf's Primary School, High Valleyfield.

On 16 May, the Committee held an evening meeting at the Muirhouse Millennium Centre, Edinburgh. The event was attended by around 50 people, including young people, parents, teachers, CLD professionals, academics and professionals from the third sector.

Links to Official Reports of the formal meetings and write-ups of the other visits and events highlighted above are published and available on the Committee's website.

The Committee has heard from hundreds of people during this inquiry. The experiences and evidence shared is the basis for the Committee's findings. The Committee thanks everyone who contributed to its work.

Membership

Gordon MacDonald MSP replaced Ruth Maguire MSP as a member of the Committee on 24 May 2018. This was after the Committee concluded its evidence gathering on this inquiry but before it had agreed this report on 27 June 2018.

Summary of recommendations

All of the Committee's recommendations in this report are reproduced below.

Impact of attainment

The poverty-related attainment gap

The Committee acknowledges that there are strengths and weaknesses in the different measures of deprivation usedi. There are likely to be imperfections in any such measurement. The Committee welcomes the work highlighted by Education Scotland to refine measures of deprivation, particularly in rural areas and asks to be kept informed of the progress on that work. The Committee also acknowledges that the Scottish Government is open to dialogue on this matter.

Given the reliance on two indicators of deprivation as the basis for the allocation of substantial amounts of targeted Scottish Government funding, both of which may under-report rural poverty, the Committee considers it is preferable under the current system of funding that swift progress is made towards developing more sophisticated indicators.

The Committee notes that the creation of a "bespoke" measure of deprivation is identified in the Scottish Government's education research strategy. The Committee seeks an update from the Scottish Government on the progress of this work.

In the meantime, the impact of using the current indicators as a basis for funding allocation should be explored further. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government assess the extent to which individuals and areas are disadvantaged by using SIMD and free school meals registration as indicators of deprivation. This includes exploring the extent of the “urban bias” highlighted in evidence from the Northern Alliance.

How does poverty impact on children and their education?

The Committee is deeply concerned that the incidence of child poverty is increasing. The Committee was appalled by some of the evidence it heard, including the amount of evidence received about children in Scotland going to school hungry.

The Committee notes that certain trends in policy, such as the increased use of digital platforms can have a disproportionate negative impact on young people living in poverty.

The Committee notes that since 2016, education authorities have had a legal duty to have regard to social disadvantage in new strategic decisions. However, this does not cover either existing policies such as the structure of the school year or more operational decisions such as the increasing use of digital platforms. The Committee recommends that during standard review processes of their schools, education authorities should undertake impact assessments on existing policies and associated practices to assess the impact on low-income families.

The Committee further recommends that education authorities ensure that school leaders are mindful of potential impacts of school practice on families with low incomes and are equipped to undertake equality impact assessments if necessary.

The Committee seeks an update from COSLA on how its members will take forward the preceding two recommendations.

The Committee is concerned that Joseph Rowntree Foundation found a significant difference in the outcomes for young people from deprived communities depending on where they live, specifically which local authority they live in. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and COSLA work together to analyse these findings and report back to the Committee by the end of 2018 on the basis for this disparity and the actions that require to be taken.

Leadership and teaching approaches

Leadership

The Committee recognises that there are many high quality and inspirational school leaders across Scotland. The Committee also recognises the value of interventions that are based on an awareness of the emotional needs of the child or young person and also the value of engaging with families in ways that are supportive to them. The Committee praises the work of headteachers, such as Nancy Clunie, which reflects these principles. The Committee also praises the collaboration and best practice sharing that is taking place in education authorities such as Fife and Glasgow.

The Committee acknowledges that effective leadership can take many forms at many different levels in schools. Regardless of which leadership model is adopted by a school, it is vital that the Scottish Government, Education Scotland and education authorities ensure there is a structure in place that supports and fosters that high quality leadership.

Achievement and a broad curriculum

The Committee recommends that Education Scotland (in its new capacity supporting the development of school leaders) identifies how it will enhance knowledge of youth work approaches among school leaders. The Committee also recommends that Education Scotland publishes a detailed plan, including targets and deadlines, on the work they are undertaking to ensure wider learning is accredited appropriately.

Teaching

The Committee has found that, in a variety of different contexts, local authorities, schools and teachers are using evidence-based techniques and getting positive results. The Committee considers that evidence to this inquiry could provide a very useful resource for other practitioners. Therefore, the Committee recommends that Education Scotland takes into account the evidence collected during this inquiry.

The Committee also recognises that there can be resource implications arising from the adoption of best practice and its adaptation to meet the needs of individuals in each classroom. The Committee reiterates its view that "a continued emphasis on reducing teacher workload is vital".1

The Committee therefore recommends that Education Scotland, through its school inspections, seeks to identify activities taking place in our schools for which there is either strong or limited evidence of improving attainment or reducing the attainment gap. The Committee further recommends that having received this advice from Education Scotland, education authorities and schools should be given the time and space to adopt activities with more robust evidence of effectiveness. This should include ensuring that Continuing Professional Development is developed and delivered in ways that have been shown to be effective.

Scottish Attainment Challenge and Pupil Equity Funding

Resources and additionality

The Committee wishes to highlight that many schools do not receive PEF and are undertaking valuable work to improve attainment using core funding. For completeness any system used to evaluate the impact of targeted Government funding must reflect progress in attainment achieved using core funding. An effective evaluation must reflect how attainment is improving, why and where the challenges, including funding levels, remain.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government's evaluation of its Attainment Scotland Fund.

The Committee recommends that as part of the next stage of this evaluation, the Scottish Government assess the extent to which PEF is used for additional purposes rather than for purposes that would be considered to be candidates to be covered from core funding.

In addition, the Committee recommends that the Scottish Government widens the evaluation to assess the separate impacts on the poverty-related attainment gap of programmes and interventions that are totally or primarily funded by:

the Pupil Equity Fund;

other aspects of the Attainment Scotland Fund; or

schools’ core budgets.

Challenges

Procurement

The Committee welcomes the work schools are doing to tackle the attainment gap. The Committee notes that headteachers are being asked to undertake new tasks as part of PEF processes, such as procurement exercises, with little preparation before they took on these new responsibilities. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland ensures that there is universally available and high quality training for headteachers on how to identify need and commission services through PEF.

Furthermore, the Committee recommends that in advance of any additional responsibilities being placed on headteachers in the future, the Scottish Government must ensure that they are provided with the necessary training and resources to undertake their expanded role. The impact on headteachers' workload of these new responsibilities should be acknowledged. When introducing new responsibilities, the Scottish Government through Education Scotland, should seek to identify ways to alleviate workload in other parts of the headteacher role.

Staffing

The Committee notes that headteachers may employ additional teachers through PEF for the remainder of the current parliamentary sessioni. However, some headteachers believe they are not able to do so. For example, there are conditions on employing teachers using PEF in the Scottish Government's guidance and it is unclear whether the requirement to "fill core staffing posts first" before employing teachers through PEF refers to the local authority or the school and this may be cause for confusion. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government makes clear in guidance the circumstances in which a headteacher may and may not employ a teacher through PEF.

Accountability

The Committee seeks further clarity on lines of accountability from the Scottish Government between headteachers and education authorities on PEF spending. The Committee also questions how a headteacher is in practice accountable to the school community, as suggested by Education Scotland. The Committee expects Education Scotland to clarify this.

The Committee notes the call from School Leaders Scotland that an accountability framework be created to evaluate headteachers' use of PEF. The Committee's experience in Fife indicated that that local authority held its headteachers accountable for, broadly speaking, the "must do" actions outlined in the Scottish Government's guidance along with pre-agreed outcomes.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government update its guidance to clarify the role of local authorities in ensuring headteachers are accountable for the outcomes resulting from PEF activities. In doing so, the Scottish Government may wish to reflect on the approach taken in Fife.

Barriers to participation

Cost of the school day - charging for school activities

The starting point to address this issue of charging for access to school education is to assess the extent of this practice. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government surveys all education authorities to establish which authorities sanction charging for in-school activities and the level of these charges.

The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government undertake a review of which elements of the experiences offered by schools may attract a charge and the cumulative impact of these charges.

Hunger

The Committee commends local authority initiatives to tackle hunger including North Lanarkshire offering free meals during holidays and Glasgow planning to provide free school meals for all pupils up to P4. The Committee appreciates the value of this work and urges the Scottish Government to support and evaluate such initiatives.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government review its current policies for funding free food in schools, taking into account evaluations of the outcomes achieved by expanded free provision of food at local authority and school levels. To take account of these developments, which are at very early stages, the review cannot take place immediately, and so the Committee recommends that it is concluded and published by the end of the current parliamentary sessioni. This review should also examine ways to improve the uptake of existing provision by families who are eligible.

Uniforms

The Committee welcomes the recent announcement from the Scottish Government and local authorities that there should be a minimum clothing allowance of £100 a year.

The Committee considers that excessively expensive or unnecessary pieces of school uniform should not be required. Reducing the complexity of school uniforms would reduce the cost burden of education on families. The Committee recommends that education authorities invite schools to poverty-proof their uniform policies.

The Committee also recommends that education authorities should consider carefully the evidence received during this inquiry of children who cannot afford to purchase or maintain school uniforms being sent home or chastised for their appearance at school. The Committee hopes this is a limited issue but considers that no pupil should be denied access to education due to the inability to afford school uniform. Schools should have an emphasis on supportive policies that are mindful of young people who, due to poverty, do not have the full school uniform.

The Committee asks that COSLA responds to the Committee by the end of 2018 to provide an update on these two issues.

Community based support and youth work in schools

The Committee recognises the distinct and important role that youth work plays in the education of our young people. The Committee recommends that the national youth work strategy currently being developed has a strong focus on how youth work and school based education can complement and support each other.

The Committee notes that improvement planning should be developed to be complementary to children's service planning, which for example includes youth work services. This appears to be the appropriate mechanism to ensure that a range of community services and providers are included in the life of a school. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland identify whether School Improvement Plans are being developed to complement community based services for children and young people in a consistent and meaningful way.

Parental involvement

Parent Councils

The Committee acknowledges that there are schools with excellent parental engagement but which do not have a parent council. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government examine the impact of not having a parent council on the funding available to schools and whether state funding, through either local authorities or the Attainment Scotland Fund, takes account of schools where it has proven difficult to establish a parent council.

Home and school partnerships

The Committee highlights the notable impact of income maximisation for some of the families where schools have acted as an initial hub and directed families towards support. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government undertakes a cost-benefit analysis of rolling out a system of using more schools as hubs for income maximisation advisory services.

Impact of poverty on attainment and education

A main focus of the Committee's inquiry has been on what can be done to support the education of children and young people who experience poverty. In doing so, the Committee has also considered and taken evidence on what the impact of poverty is, how to measure deprivation, and how much of an impact education can have on children's outcomes.

Growing up in poverty does not mean a child will underachieve. However, the evidence the Committee took was clear that living in poverty has an effect on the family unit which then can impact on a child's learning. This is reflected in data that shows that there is a gap between the attainment of children and young people in the most and least deprived areas of Scotland.1

The poverty-related attainment gap

The gap in attainment between children and young people living in our most and least deprived areas is known as the "attainment gap".

The OECD defines educational attainment as the "highest grade completed within the most advanced level attended in the educational system of the country where the education was received. Some countries may also find it useful to present data on educational attainment in terms of the highest grade attended". In debates in Scotland and elsewhere it is often used as a shorthand for measurable progression in formal education.

The Scottish Government uses the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation ("SIMD") as a measure of poverty. The attainment gap is defined as the difference of attainment between individuals living in the highest and lowest quintile (20%).

The Scottish Government consulted on how to measure the poverty related attainment gap in 2017. The Scottish Government has identified 11 key measures to gauge progress in reducing the gap - these measures include health and well-being measures as well as academic attainment. The Scottish Government also published benchmarks setting out what the current attainment gaps are for those measures.1

The Scottish Government's goal is to make "demonstrable progress in closing the gap during the lifetime of this Parliament, and to substantially eliminate it in the next decade."2

To help achieve this goal, the Scottish Government is committed to spending £750 million on its Scottish Attainment Challenge ("SAC") over the course of the current parliamentary session (to April 2021). This funding is being spent on SAC funding for nine "challenge" local authorities and a number of individual schools based on levels of deprivation as measured by SIMD and Pupil Equity Funding ("PEF") which is allocated to individual schools based on free school meal registrations.1 Education Scotland explained that as well as the targeted funding, there is a universal offer to support all teachers and schools,4

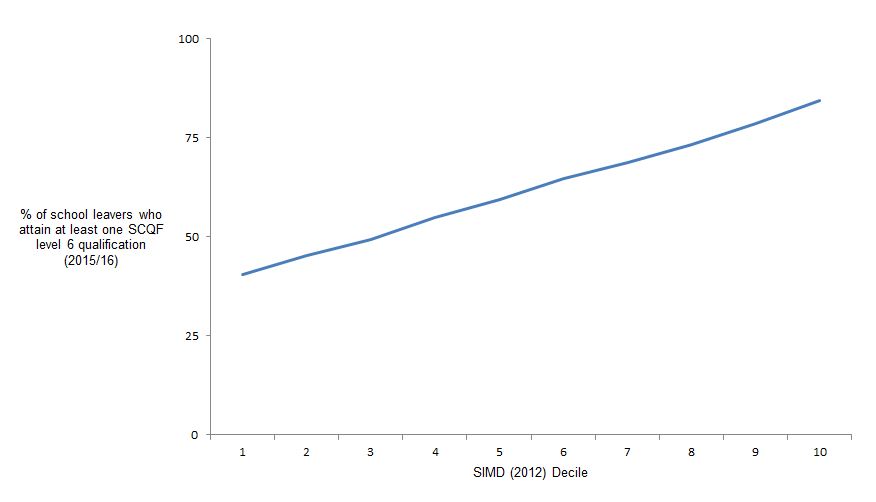

The graph below shows that attainment increases steadily for young people, the less deprived the area is in which they live. Here the measure of attainment is obtaining one or more SCQF level 6 qualification. (e.g. Higher, or better). The Committee is aware that while the gap between the most and least deprived areas is important, there is positive correlation between educational outcomes and parental income all the way through the income scale.

Graph showing positive relationship between SIMD decile and attainment.Scottish Government. (2017). Attainment and school leaver destinations (supplementary data) 2015/16 (Table A1.1b). Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/School-Education/leavedestla/follleavedestat

How accurate are the indicators used to measure deprivation?

The Committee heard evidence that measures of deprivation are imperfect and that designing a system that could adequately identify the different impacts of deprivation is complex. For example the density of poverty in different areas of deprivation, whether rural or urban, is difficult to measure accurately. In addition the Committee heard evidence of a growing number of families that are experiencing poverty despite working long hours in full time jobs. This form of poverty can be challenging to identify, not least because some people in this situation would not necessarily choose to self-identify as experiencing poverty. In addition the deprivation levels in an area can impact on and put pressures on services including education, and this impacts on people regardless of whether they are directly experiencing poverty.

SIMD measures levels of deprivation in small local areas. The Northern Alliance highlighted that SIMD tends to highlight concentrations of deprivation and thus has an "urban bias" while missing a significant number of individuals living in rural poverty.1 The Committee explored how the concentration of deprivation affects services and therefore outcomes in Scotland's communities. He said—

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged that SIMD is not an individualised measure.

[SIMD] is a good measure for identifying substantive groupings and areas of poverty, it is not good at identifying individual instances of poverty. The free school meals eligibility criteria give us a more comprehensive presentation of the prevalence of poverty, which results in about 95 or 96 per cent of schools receiving some pupil equity funding.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], John Swinney, contrib. 157, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095929

Free school meals' registration was also criticised by some as a measure. The Poverty Alliance highlighted stigma as being a barrier to accessing free school meals, where children and young people could be identified as accessing free school meals.3 This stigma may prevent some from registering for free school meals, especially in more affluent areas where free school meals are less common or in smaller schools. On this issue, the Cabinet Secretary said that he is open to dialogue about alternative measures. He said—

Eligibility for free school meals is the most comprehensive mechanism that is available to me. I am happy to engage in dialogue about how we could find a more comprehensive mechanism because I fundamentally accept [...] the prevalence of poverty possibly being more difficult to identify in rural communities. In smaller schools, families might be reluctant to come forward and say that their children are eligible for free school meals because such eligibility is slightly more obvious in a school of 20 pupils than it is in a school of 200 or 300 pupils.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], John Swinney, contrib. 157, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095929

The Scottish Government's education research strategy which was published in April 2017 states that it will explore "a study on the long-term development of a bespoke index of social background which will create individual-level (as opposed to area-based) data involving consideration of the data collected at school registration." The strategy continued—

A bespoke index will enable more targeted and effective intervention for disadvantaged pupils, and also better take into account disadvantage of those who do not live in deprived areas (usually the greater share of deprived students).

Scottish Government. (2017). A Research Strategy for Scottish Education. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00512276.pdf

Education Scotland indicated that it was continuing to work with the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland on refining measures of deprivation, especially to better reflect poverty in rural areas. Gayle Gorman, Chief Executive of Education Scotland said—

Significant work has been done, and this year PEF funding has gone to more schools across Scotland. However, further work could be done to reflect rural poverty and deprivation, because significant parts of Scotland fall into that category.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], Gayle Gorman, contrib. 101, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095873

The Committee acknowledges that there are strengths and weaknesses in the different measures of deprivation used. There are likely to be imperfections in any such measurement. The Committee welcomes the work highlighted by Education Scotland to refine measures of deprivation, particularly in rural areas and asks to be kept informed of the progress on that work. The Committee also acknowledges that the Scottish Government is open to dialogue on this matter.

Given the reliance on two indicators of deprivation as the basis for the allocation of substantial amounts of targeted Scottish Government funding, both of which may under-report rural poverty, the Committee considers it is preferable under the current system of funding that swift progress is made towards developing more sophisticated indicators.

The Committee notes that the creation of a "bespoke" measure of deprivation is identified in the Scottish Government's education research strategy. The Committee seeks an update from the Scottish Government on the progress of this work.

In the meantime, the impact of using the current indicators as a basis for funding allocation should be explored further. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government assess the extent to which individuals and areas are disadvantaged by using SIMD and free school meals registration as indicators of deprivation. This includes exploring the extent of the “urban bias” highlighted in evidence from the Northern Alliance.

How does poverty impact on children and their education?

The Committee heard evidence of a number of ways in which poverty can impact on a child and their education and that poverty is a growing issue for children and young people in Scotland. The Committee is aware that this is a complicated and multifaceted issue and wants to highlight a snapshot of evidence at the outset that highlights the types of experiences and evidence raised during the inquiry.

John Loughton spoke about the stress inherent to poverty and told the Committee—

I liken living in poverty to sitting on a chair that has had three of its legs removed: every part of you is tensed in order to keep balanced; the slightest movement, wind or meander and you will go. [...] When you are surviving, how can you think about thriving, culture or creativity? Why would you think of yourself in the asset model, rather than thinking about the deficits that everyone knows you for?

Education and Skills Committee 25 April 2018 [Draft], John Loughton, contrib. 62, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11490&c=2086367

Children coming to school hungry was a theme that arose frequently in the Committee's evidence. Dr James Foley from North Lanarkshire Council told the Committee that headteachers and other professionals always raise hunger in discussions on poverty; he said "they think that it has a significant impact on their pupils’ ability to learn."2 In the Committee's meeting at the Muirhouse Millennium Centre on 16 May, the Committee was told that breakfast clubs "ensure young people can go to school with a full stomach and ready to learn"3

The Committee also heard examples of how family homes can lack the resources to support children to do their homework. In primary school, this could be craft materials such as glue or glitter4 and in secondary school, that could be access to IT or the internet. The Poverty Alliance said in their submission—

Ensuring free and consistent access to the internet for all children is a necessity in order to support their learning. Yet many children do not have access to a computer at home and, if they do, access to the internet cannot always be guaranteed due to cost.

Education and Skills Committee. (n.d.) Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p33). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

A number of organisations (e.g. Glasgow Centre for Population Health6) also highlighted the benefits of having a quiet space in the home to do homework, which is not always the case for families in crowded accommodation. As well as space, the Committee heard that some families cannot afford basic amenities such as hot water for showers or beds which can impact on young people's attendance at school and readiness to learn when they are there.7

A number of respondents to the Committee's call for views and people the Committee spoke to were clear that the concept of "poverty of aspirations" is a myth. Dr Morag Treanor has undertaken research into this topic and in her submission to the Committee said—

The evidence shows that poorer parents are more likely to aspire to apprenticeships/training/further education and less likely to aspire to higher education for their children. Parents’ aspirations may differ by poverty experience, but can only be thought of as ‘high’ aspirations [...] Aspirations, even in communities struggling with poverty, are very high – the missing element is the knowledge of how to make these aspirations real and obtainable.

Treanor, D.M. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p363).

An increase in child poverty

The Committee heard evidence that teachers are increasingly seeing children who are affected by poverty. Andrea Bradley from the EIS said—

Where the school policy is to wear uniform, they were perhaps not able to sustain wearing it every day. Kids were not able to participate in school trips, did not bring in homework or turned up for PE lessons without the requisite kit [...] Some kids come into school and tell teachers that they are hungry; some steal food or items of equipment from one another at times; and some appear visibly unwell—pale and complaining of headaches—or have unexplained absences from school.

All those factors were combining to suggest to our teachers that there was an increased incidence of poverty. They thought that those things were attributable to the income circumstances of families in their school communities.

Education and Skills Committee 25 April 2018 [Draft], Andrea Bradley, contrib. 46, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11490&c=2086351

John Dickie from CPAG Scotland said—

There is no question that families are under increased and increasing pressure. That is primarily as a result of cuts in the benefits, tax credits and financial support available, alongside stagnating wages. Low-income families have faced a real squeeze on their incomes and more and more have been pushed below the poverty line. All the projections are that that will continue, as cuts to the financial support available to families kick in and accumulate.

Education and Skills Committee 18 April 2018, John Dickie, contrib. 13, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11471&c=2083316

Dr Jim McCormick from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation said that "child poverty is now rising again, after 20 years of progress"3 and stated—

On the dominant drivers of child poverty in Scotland, in particular the increase that we are likely to see—all things being equal—by the end of this decade, which John Dickie mentioned, the most consistent finding from the evidence is that aspects of UK social security policy are the single biggest reason for the increase, followed by what is happening at the bottom end of the jobs market [...] In particular, when we consider what Governments do directly, the benefit freeze, which I think is to be reviewed in a year or two, has already caused great damage in the context of poverty rates.

Education and Skills Committee 18 April 2018, Dr McCormick, contrib. 45, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11471&c=2083348

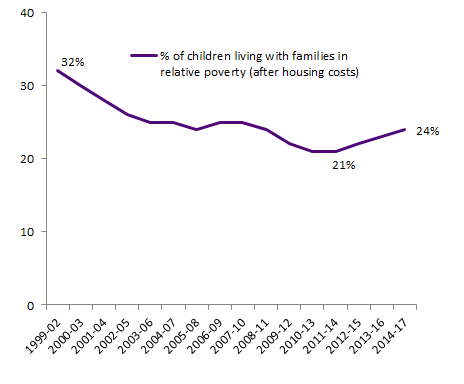

The Scottish Government’s Poverty and Income Inequality Statistics show that the numbers of children in poverty has been increasing since 2011/12. On the measure of the percentage of children living in relative poverty after housing costs, in 1999/2000 the figure was 32%, this dropped to 19% in 2011/12 and is 23% in 2016/17 (the latest figures available).5 This is illustrated in the graph below, where the data is presented in 3-year rolling averages.

The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 requires the Scottish Government to reduce the number of children who live in poverty by 2030. One target is to reduce to less than 10% children living in households in Scotland in relative poverty after housing costs (relative poverty defined as a household with less than 60% of UK median income in the same year).7

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledges that at least to some degree "the Scottish Government has opportunities to use our policy instruments to address [rising levels of poverty]".8 He also stated—

The Scottish Government makes active representations, publicly and privately, to the UK Government on welfare reform. We consistently set out our concerns about the welfare reform agenda and its implications for children and families in Scotland.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], John Swinney, contrib. 153, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095925

How can education be 'poverty proofed'?

Schools cannot be expected to provide solutions for all of the negative impacts of poverty on education attainment and achievement. A Joseph Rowntree Foundation paper on this topic stated that—

Just 14 per cent of variation in individuals’ performance is accounted for by school quality. Most variation is explained by other factors, underlining the need to look at the range of children’s experiences, inside and outside school, when seeking to raise achievement.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2007). Experiences of poverty and educational disadvantage. Retrieved from https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/2123.pdf

The Committee has heard about a great deal of good policy and practice by education authorities, schools, delivered in the community or in the family home that demonstrate understanding of the challenges faced by those experiencing poverty. For example, during the Committee's informal meeting on 2 May, an Edinburgh primary school headteacher explained that her school’s homework policy is that a child should not be put under pressure if they have not done their homework. This policy recognises that not all families will have the time or resources to support their children in homework tasks.2

Other policies, however, were highlighted as poor practice, as they did not take account of some of the barriers to learning that poverty creates. For example, the move to online payment systems for school trips and dinners presupposes access to the internet and may create digital exclusion.34 As previously mentioned, digital exclusion can affect homework. The Poverty and Inequality Commission said in its submission—

The Commission [has heard about] costs being shifted from schools to families, for example through expectations that all families will have access to a computer to carry out homework and a printer to be able to print out material that is a core part of learning. Pupils are not always able to access these resources in school if they do not have them at home.

Poverty and inequality Commission. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p37). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The Committee heard that seemingly small asks of families can lead to significant costs. With respect to school uniforms for example Brian Scott from the Poverty Truth Commission said—

For parents who have a few kids at school, it is a massive pressure on their budget and finances to have to go out at the start of a new term to change everything again. If the school decides to change colours or whatever, that negates the possibility of even handing the clothes down to younger children.

Education and Skills Committee 02 May 2018, Brian Scott, contrib. 12, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11508&c=2089275

One health professional who attended the Committee's informal meeting on 2 May 2018 questioned why equality impact assessments were not undertaken for changes of policy which had a disproportionate impact on families living in poverty, such as a move to online payment systems.2

The Committee also explored whether the structure of the school year and particularly the long summer break negatively impacts on families experiencing poverty. Referring to research from the USA on the impact of the long summer break, Lindsay Graham said in a letter to the Committee—

Many of those living in poverty may have been socially isolated, not had access to regular meals, limited outside play or physical activity and little of the ‘fun’ that other more privileged children might experience during the breaks.

Graham, L. (2018). Education and Skills Committee, Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty(p371). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The Education (Scotland) Act 2016 requires that when education authorities are making strategic decisions, they must have regard to reducing inequalities of outcome for pupils experiencing socio-economic disadvantage. Dr McCormick from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation ("JRF") told the Committee that it had been supporting local authorities to ensure that their budgeting decisions protect low-income people and areas and to be mindful of the impacts of these policy decisions.[15]

The 2016 Act does not apply retrospectively meaning all policy established before the Act’s implementation have not been developed in this way. In addition, the Act does not apply to lower level operational decisions and the Committee heard evidence of new practices commencing that may not align with the strategic direction of the 2016 Act.

The Committee heard evidence from JRF that the outcomes for young people from deprived areas "varies substantially" across different local authorities. JRF looked at the percentage of young people from the most deprived areas attaining five or more Level 5 passes across different local authorities. It found that while in the best performing local authorities (East Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire) the percentage was over 50%, in one (Aberdeenshire), it was less than 20%. As well as Aberdeenshire, other local authorities that JRF highlighted as having a lower performance on this measure were Aberdeen City, Stirling, Scottish Borders, and Clackmannanshire. JRF's submission stated—

The reasons for this are not fully understood, but we can speculate that these are likely to include school leadership and culture, use of data to inform practice, improvements in teaching methods, targeted resourcing and relationships with families, communities and wider stakeholders.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p26-27).

The Committee is deeply concerned that the incidence of child poverty is increasing. The Committee was appalled by some of the evidence it heard, including the amount of evidence received about children in Scotland going to school hungry.

The Committee notes that certain trends in policy, such as the increased use of digital platforms can have a disproportionate negative impact on young people living in poverty.

The Committee notes that since 2016, education authorities have had a legal duty to have regard to social disadvantage in new strategic decisions. However, this does not cover either existing policies such as the structure of the school year or more operational decisions such as the increasing use of digital platforms. The Committee recommends that during standard review processes of their schools, education authorities should undertake impact assessments on existing policies and associated practices to assess the impact on low-income families.

The Committee further recommends that education authorities ensure that school leaders are mindful of potential impacts of school practice on families with low incomes and are equipped to undertake equality impact assessments if necessary.

The Committee seeks an update from COSLA on how its members will take forward the preceding two recommendations.

The Committee is concerned that Joseph Rowntree Foundation found a significant difference in the outcomes for young people from deprived communities depending on where they live, specifically which local authority they live in. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and COSLA work together to analyse these findings and report back to the Committee by the end of 2018 on the basis for this disparity and the actions that require to be taken.

Leadership and teaching approaches

A recurring theme across a number of different strands of the Committee's work has been the importance of high quality teaching and leadership in schools. In this inquiry both were highlighted as central to closing the attainment gap. In its submission, the Robert Owen Centre for Educational Change ("ROC") told the Committee that the key drivers for schools to make a difference to the outcomes of their pupils were—

First, schools should invest in teachers’ professional development so that teachers develop a wide repertoire of teaching skills that can reflect the range of needs of their learners. Second, a focus on building leadership capacity at all levels within the school is key to success, as is leaders promoting a culture underpinned by high expectations and positive norms in staff and pupils.

Robert Owen Centre for Educational Change. (2018). Education and Skills Committee, Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty(p47). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The ROC continued to highlight the importance of collaboration and taking a holistic approach to tackling the attainment gap.1

Leadership

The Committee spoke to a number of headteachers in different local authorities. While their personalities differed, the Committee was impressed at the clear leadership abilities of all of those individuals.

Nancy Clunie, the Headteacher of Dalmarnock Primary School in Glasgow appeared at Committee on 2 May 2018. 94.7% of the children in Dalmarnock Primary School are in the first quintile (20% most deprived) SIMD zones. Nearly 50% of Dalmarnock pupils are entitled to free school meals and there are a relatively high number of looked after children.1

Ms Clunie had a clear focus and sense of ownership of the wellbeing of her pupils and her school community. This report will explore the detail of some of the programmes she has undertaken later in this report. It was, however, clear that her passion allied to her considerable skill and tenacity made a huge difference to her school.

Ms Clunie told the Committee of her efforts to get every parent involved in the life of her school—

We have the parents who are very keen to be a part and we have got on board the parents who have been reluctant because of language barriers, but there are some parents who we are not getting, so we want to know what would enable us to reach them. [...] We need to explore that and we need to ask them. If that means knocking on doors, that is what we will do. If you will not come to a coffee morning, I will come to you—there is no escape.

Education and Skills Committee 02 May 2018 [Draft], Nancy Clunie, contrib. 108, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11508&c=2089371

In relation to drawing in support and resources locally and nationally, Ms Clunie said—

I am not a shrinking violet, so if I need help, I go out and find it. [...] It has just been a case of donning the brave pants and picking up the phone. The worst that they can say to me is, “Away you go,” but nobody ever does.

Education and Skills Committee 02 May 2018 [Draft], Nancy Clunie, contrib. 86, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11508&c=2089349

During a visit to Queen Anne High School in Dunfermline, the Committee learned about a variety of measures that had been put in place to support young people. The programmes were focused on: broadening young people's experience; health and wellbeing; and reducing costs and barriers to participation. Many of these programmes were initiated by other leadership team members, teaching staff and pupils themselves. Nonetheless, the Rector, Ruth McFarlane, had a very clear vision of the purpose of each of the programmes and an understanding of how successful they were.4

The Committee also met with the Headteacher and staff from St Serf’s RC Primary School in High Valleyfield. St Serf's is in receipt of school-level Scottish Attainment Challenge funding and the Headteacher, Catherine Mullen, candidly explained to the Committee that she and her team had been on a steep learning curve in developing, measuring and delivering interventions that improve attainment. St Serf's improvement model has required the school and teaching staff to learn how to measure outcomes and collect and analyse data. This includes benchmarking and interim targets. Ms Mullen explained that having a robust system of measurement has allowed teachers to take more risks and try new things. If something is not working, the data will show this and approaches can be changed.4 Similarly at the local authority level, the Committee was told that across Fife, the relationship between the local authority and headteachers is characterised by trust, support, autonomy and accountability for performance.6

The Committee was keen to establish how positive leadership and effective practice can be shared across schools and education authorities. Following Nancy Clunie's evidence session, the Committee sought supplementary written evidence from the education authority for Glasgow on how it ensures best practice is shared and headteachers can collaborate across the education authority. The response from Glasgow City Council details the approaches that enable collaboration from the principles of good leadership down to very practical ideas. It said—

Our primary schools are put into clusters of between three and five primary schools. Each cluster has a Challenge link officer [...] who meets with the headteachers and carried out quality visits throughout the year. This approach allows us to actively promote the sharing of good practice and provide challenge and support. We also share practice through our regular headteacher meetings. We also have a Leaders of Learning team who support schools across the city, modelling good practice and sharing the good practice that they see as they work across schools. Our Headteacher Learning and Teaching maintains the overview of our work on the Challenge. Evidence is systematically gathered and then shared regularly through becoming a focus for training run by the Challenge team.

Glasgow City Council. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p76). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

In terms of what constitutes good practice, it is clear that there will be a variation as to what works for different schools, and what works for each individual child in those schools.

The Committee recognises that there are many high quality and inspirational school leaders across Scotland. The Committee also recognises the value of interventions that are based on an awareness of the emotional needs of the child or young person and also the value of engaging with families in ways that are supportive to them. The Committee praises the work of headteachers, such as Nancy Clunie, which reflects these principles. The Committee also praises the collaboration and best practice sharing that is taking place in education authorities such as Fife and Glasgow.

The Committee acknowledges that effective leadership can take many forms at many different levels in schools. Regardless of which leadership model is adopted by a school, it is vital that the Scottish Government, Education Scotland and education authorities ensure there is a structure in place that supports and fosters that high quality leadership.

Achievement and a broad curriculum

The Committee took evidence that achievement is crucial in supporting young people. Education Scotland defines achievement as "learning also takes place outside the classroom, at home and in the wider community [...] and in the variety of activities children and young people are involved in". Education Scotland highlights some examples of what this means in practice, such as sport, outdoor pursuits or youth work.1

Non-formal education can be crucial in building confidence and trust for young people and particularly those who have disengaged with formal education. Eileen Prior from Connect argued that—

When we talk about the attainment gap, we are often talking about the experience gap.

Education and Skills Committee 25 April 2018 [Draft], Eileen Prior, contrib. 38, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11490&c=2086343

Dr Terry Wrigley argued that growing up in poverty can have psychological effects, "which damage self-esteem and cause demoralisation".3 John Loughton said that in his youth "nobody expected anything of me, so I started to live down to that expectation and felt a lack of confidence" but "it was the people in youth work or non-school provision who caught me, captured my imagination and told me that I could be more than the collective sum of the lack of aspiration that everyone had for me because of my postcode, my surname and what my mum and dad did—or did not do."45

In its submission, the Duke of Edinburgh's Award ("DoE") quoted research and testimony that showed that participation in DoE programmes increases confidence, mental health, team working, resilience and communication skills as well as numeracy and literacy.6 The Prince's Trust highlighted its Achieve programme which is delivered in secondary schools to prepare young people with life skills. Two young people who are in the Achieve programme and their teacher took part in an informal discussion with members of the Committee on 25 April 2018. The teacher told Members that “pupils flourish on the programme, those who were not engaging with their learning go onto better engagement and increased confidence.”7

Those young people also said that others in their school, including teachers, looked down upon the Achieve group. This lack of esteem from teachers of a youth work approach being taken in schools was reflected in a discussion group the Committee held with public sector Community Learning and Development professionals. Partially this was put down to a lack of understanding of the value of youth work and achievement-based learning, but partly there were cultural barriers. One participant in the discussion reported that some teachers have objected to the pupils who had disengaged with school participating in DoE and other Youth Achievement activities as they feel these pupils are being rewarded for bad behaviour. Good relationships with the senior leadership teams ("SLT") in schools were identified as crucial by the whole group. The participants said that where a member of the SLT understands and values CLD, the school will be supportive and ensures that space is created for CLD programmes and projects through the year.8

Secondary schools' success however is not measured by pupils' achievement; rather success is often measured by formal exam results. Gayle Gorman, Chief Executive of Education Scotland, recognised that school leaders might be discouraged from investing PEF monies into achievement-based activities if the achievements are not fully recognised and accredited in a similar way to National qualifications.

We are working with many of the partners that are seeking recognition for their awards so that they can be registered and added to the accreditation portfolio. That will enable such achievement to be celebrated. It should be; it is sad that it is not. [...] We continue to have dialogue with the SQA and other partners. We continue to advocate wider learning and parity of esteem for that wider learning.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], Gayle Gorman, contrib. 81, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095853

Broader achievement is vital to our young people in developing confidence and soft skills. This in turn helps with attainment in schools by giving children and young people the confidence and capacities to tackle a range of subjects. Children from poorer households face a double disadvantage - their families are less able to fund wider activities that create opportunities for rich experiences, and poverty can create or worsen confidence issues. For some, this lack of confidence and other issues may lead to disengagement with school and education. CLD and third sector programmes clearly constitute a valuable support to young people and the schools that utilise them.

In addition,if schools feel they are strategically directed towards delivering qualifications and other achievements traditionally associated with attainment then those who may not consider they want to pursue such routes can feel 'outside the system'. The importance of feeling on a par with peers and treated in the same way was clear in the evidence received.

The Committee recommends that Education Scotland (in its new capacity supporting the development of school leaders) identifies how it will enhance knowledge of youth work approaches among school leaders. The Committee also recommends that Education Scotland publishes a detailed plan, including targets and deadlines, on the work they are undertaking to ensure wider learning is accredited appropriately.

Teaching

The Education Endowment Foundation ("EEF") said in its submission to the Committee—

There is evidence that improving the quality of teaching is likely to have a disproportionately positive impact on children from low-income families, and that the quality of teaching is generally lower in schools serving disadvantaged communities.

Examples of cost-effective strategies that focus on teaching quality, include the use of metacognitive [learning to learn] strategies, reading comprehension strategies, and the provision of effective feedback.

Educational Endowment Foundation. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p21). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre's ("SPICe") 2016 briefing Closing The Attainment Gap: What Can Schools Do? highlighted high quality teaching and learning as a key aspect for schools to close the attainment gap. The briefing was authored by Geetha Marcus, an education specialist and former headteacher. The briefing identified circumstances when teachers can best make a difference to pupils' outcomes. These are:

highly trained and effectively deployed teachers;

teachers who are granted greater autonomy to be active and creative drivers of change;

teachers who are research literate;

teachers who have an understanding of the impacts of poverty and other inequalities.2

This was echoed in the submission from the Robert Owen Centre for Educational Change ("ROC") whose key message was "that for improvement in academic outcomes for young people to occur there must be a focus on improvements in the quality of learning and teaching". 3

ROC suggested that a Collaborative Action Research approach be taken "to identify priorities for change, implement improvement strategies and track and monitor the impact of these interventions".3 The Committee spoke to teachers using this approach during its visit to Dunfermline5 and Education Scotland noted it is being used as part of the Scottish Attainment Challenge.6

As well as hearing about teaching interventions and approaches that can be effective in closing the attainment gap, the Committee also heard about practice that has been shown to have a negative impact on the attainment gap. Strathclyde University (and others including the EEF and EIS) highlighted setting and streamingi as one such practice.

Setting and streaming in primary and secondary sectors enshrines disadvantage: Children in poverty tend to be placed in low attainment groups and make less progress and often suffer a ‘pedagogy of poverty’.

Strathclyde University. (2018). Education and Skills Committee, Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p269). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

Dr Terry Wrigley also cautioned against setting and streaming and 'pedagogies of poverty'. He called for Scotland to adopt "teaching for excellence" which gets pupils "thinking harder and more critically, taking initiatives, solving problems, developing creativity. Many children in poverty need extra attention to basic skills, but this should be done in the context of interesting and challenging activities."8

Furthermore, while a broader curriculum that includes vocational training was widely welcomed, Shelagh Young from Home-Start UK said—

I would not want to see a notion that we have a twin track so that children who enter school behind the curve go down a vocational route, and we accept that as achievement.

Education and Skills Committee 09 May 2018 [Draft], Shelagh Young, contrib. 61, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11523&c=2091671

High quality Continuing Professional Development ("CPD") is key to support our teachers to improve teaching and learning in the classroom. Danielle Mason from the EEF told the Committee that—

There is a good base of evidence about the type of CPD that works. We are talking about longer-term interventions that are relevant to teachers’ day-to-day expertise and build a strong relationship between peers who are doing the training and the trainer.

Education and Skills Committee 18 April 2018, Danielle Mason, contrib. 23, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11471&c=2083326

North Ayrshire Council has funded a Professional Learning Academy through its Scottish Attainment Challenge funding which appears to have followed the approach the EEF advocates. John Butcher, Executive Director of Education and Youth Employment, North Ayrshire Council, explained the approach to the Committee—

The difference between the training at the professional learning academy and the training that I went to as a young teacher [...] is that in my training there was often very little follow-up. You went to something, you learned something and you may or may not have implemented it. The professional learning academy follows up the training: teachers go for training and staff development and it is followed up with coaching and mentoring so that they implement in the class the practice that they have learned. [...] It has made a huge difference.

Education and Skills Committee 09 May 2018 [Draft], John Butcher, contrib. 108, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11523&c=2091718

Nancy Clunie, Headteacher of Dalmarnock Primary School, said that she had used PEF to provide CPD for her teaching staff "in various therapies so that we can offer children sessions at lunchtime and after school" supporting her pupils' health and well being.12

The Committee is mindful that workload is an ongoing issue for teachers in Scotland. In its report Teacher Workforce Planning for Scotland's Schools the Committee recommended that—

A continued emphasis on reducing teacher workload is vital in ensuring the education reforms proposed by the Scottish Government, and the Curriculum for Excellence, can be implemented with minimal impact on teachers and, by extension, on children and young people's education.

Education and Skills Committee. (2017). Teacher Workforce Planning for Scotland's Schools (paragraph 138). Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/ES/2017/9/1/Teacher-Workforce-Planning-for-Scotland-s-Schools/10th%20Report,%202017.pdf

It is clear that there is a desire from a broad range of stakeholders for teachers to take an evidence-based approach to their practice. In terms of the impact on teachers' workload the EEF said—

Adopting evidence-based approaches to improving attainment for disadvantaged pupils requires time for selection, implementation and evaluation of such approaches. In numerous process evaluations for programmes evaluated in England, time and workload have been cited as key barriers to the effective delivery of approaches.

Time for implementing successful interventions can often be made through critically assessing and stopping existing practices that are not having positive impacts on learning.

Educational Endowment Foundation. (2018). Education and Skills Committee Submissions Pack Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p21). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The Association of Heads and Deputes in Scotland ("AHDS") and the EIS highlighted the need to protect teachers' and other educational staff's time. AHDS reported that its members (primary school leaders) had identified a lack of resources, particularly teachers, as a key barrier to improving learning and teaching.15 The EIS said—

There is no cheap way of delivering an education system that is both excellent and equitable. Only long-term, protected investment will deliver that worthy ambition.

EIS. (2018). Education and Skills Committee, Submissions Pack: Attainment and achievement of school aged children experiencing poverty (p96). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Education/Inquiries/20180418Poverty_and_Attainment_Submissions_Pack.pdf

The Committee has found that, in a variety of different contexts, local authorities, schools and teachers are using evidence-based techniques and getting positive results. The Committee considers that evidence to this inquiry could provide a very useful resource for other practitioners. Therefore, the Committee recommends that Education Scotland takes into account the evidence collected during this inquiry.

The Committee also recognises that there can be resource implications arising from the adoption of best practice and its adaptation to meet the needs of individuals in each classroom. The Committee reiterates its view that "a continued emphasis on reducing teacher workload is vital".13

The Committee therefore recommends that Education Scotland, through its school inspections, seeks to identify activities taking place in our schools for which there is either strong or limited evidence of improving attainment or reducing the attainment gap. The Committee further recommends that having received this advice from Education Scotland, education authorities and schools should be given the time and space to adopt activities with more robust evidence of effectiveness. This should include ensuring that Continuing Professional Development is developed and delivered in ways that have been shown to be effective.

Scottish Attainment Challenge and Pupil Equity Funding

The Scottish Government has ear-marked £750m in its Attainment Scotland Fund over the course of the current Parliamenti to target "improvement activity in literacy, numeracy and health and wellbeing" particularly for children who experience deprivation.1 The Scottish Government stated that it will invest £179m in the current financial year via three main elements:

£120m of Pupil Equity Funding is allocated directly to schools, on the basis of the number of children registered for free school meals, to help schools deliver activities and interventions that support children affected by poverty.

The Challenge Authorities and Schools Programmes that provide targeted support to the local authorities and schools with the largest concentration of pupils living in deprived areas based on SIMD.ii The Schools Programme supports 46 primary schools and 28 secondary schools with the highest concentration of children living in SIMD deciles 1&2 across 12 other authority areas.

In addition, the fund supports a range of national programmes, such as new routes into teaching, continuous and lifelong professional learning, and partnership working.1

Through the course of the inquiry, the Committee has heard of good practice being funded through these schemes. This report has already mentioned the Professional Learning Academy in North Ayrshire and the work at St Serf's Primary in Fife funded through the Scottish Attainment Challenge ("SAC").

The Committee has also been provided with evidence from local authorities, schools and third sector organisations about the work that is being funded through the Pupil Equity Fund ("PEF"). The Committee was told in written submissions about:

A Falkirk Primary School that spent PEF on a supply of clothes which led to “improved self-esteem and engagement in learning. One pupil is now taking a full part in PE due to having an appropriate and fitting gym kit.” (Reported by CPAG p17)

Nurture and Transition Groups which allow children the opportunity to address concerns they may have around peer relationships, school or other issues that they may feel anxious about. (Reported and delivered by OPFS p120)

Family Support Workers. (Reported by and delivered by Barnardo's Scotland p133)

Intergenerational projects providing opportunities for older people to mentor/tutor in schools. (Reported by Generations Working Together p196)

Big Hopes, Big Future home-based support to help families to get actively involved in early learning through a range of play-based activities. (Reported and delivered by Home-start UK p198)

Outdoor education trips (Reported by the Scouts p221)

Counselling. (Reported and delivered by The Spark p237)

Bringing youth workers into the school (Reported by YouthLink Scotland p246)

A cluster of schools employing a welfare rights advisor in school to support income maximisation for families. (Reported by NHS Scotland- Facing up to Poverty Practice Network p320)

This is of course just a snapshot and there was much more practice identified to the Committee throughout the course of the inquiry.

Many of the interventions the Committee heard about are focused on the health and wellbeing of the child and indeed the success of the family unit. Kirsten Hogg from Barnardo's told the Committee that "health and wellbeing underpin a child’s ability to learn and underpin the whole attainment agenda"3. She also said—

When we are looking at interventions with children, let us also think about what else is happening in their homes, because the stress levels that impact on the rest of the family have a knock-on effect on the child—on their attachment relationships and the levels of stress that they experience. Yes, let us do the things [like supporting income maximisation], but let us try to look at everything in the round within the family.

Education and Skills Committee 02 May 2018 [Draft], Kirsten Hogg, contrib. 35, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11508&c=2089298

The Attainment Scotland Fund ("ASF") was introduced in 2015. The Scottish Government evaluated the first two years of the fund and a report was published in March 2018. The report found that the fund had "appeared to have had a positive impact" on: collaboration; data/evidence usage and understanding; and skills development for teachers and school leaders. In terms of the scope of interventions, the report said—

Numeracy, Literacy and Health and Wellbeing. During the first two years, Literacy and Health and Wellbeing interventions were prioritised. Progress around Numeracy was less evident.

Scottish Government. (2018). Evaluation of the Attainment Scotland Fund - interim report (Years 1 and 2). Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0053/00532725.pdf

The interim evaluation report only considered the first two years of the ASF and therefore did not evaluate PEF, which was introduced in the third year. The report states that "a final evaluation report will be published at the end of Year 4".5

Resources and additionality

The was some discussion at Committee about whether PEF enabled services to be reinstated that had previously been funded through normal local authority funding. A number of contributors to the Committee's inquiry placed the work to reduce the attainment gap and the Attainment Scotland Fund in the context of reducing resource budgets for local authorities. COSLA said that "since 2010/11 there has been a real terms reduction of £513 in spending per primary pupil, representing a 9.7% reduction"; with the per pupil reduction in spending mainly arising from increasing pupil numbers.1

One teacher said that "PEF money is a sticking plaster – it is merely a re-injection of the money that has been stripped out of Scottish Education over the past decade".2 Furthermore, NASUWT said "regrettably, while core services continue to be cut and support staff removed, PEF will not deliver the impact needed in reducing the poverty-related attainment gap."3

Nancy Clunie, Headteacher of Dalmarnock Primary School, argued that while there is a limit to budgets the solution lies in innovative approaches. In terms of PEF, she said—

I have not used pupil equity funding for anything that should come from the school budget, and my school budget is such that I have been able to do many a thing. PEF has been extra—I make that very clear. [...] Our view is that PEF is to make a difference, and I do not want the two merged. The school budget certainly covers what it should be covering, and PEF has allowed us to do things like residential trips, which had stopped for my school because only a few people could afford them. This year, we had 56 children away for a week, and those are the kind of weeks that children never forget. It is about building memories.

Education and Skills Committee 02 May 2018 [Draft], Nancy Clunie, contrib. 127, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11508&c=2089390

The Cabinet Secretary recognised in his evidence that there has been a period of financial constraint in the public sector. As noted above, the Scottish Government's guidance says PEF must "deliver activities, interventions or resources which are clearly additional to those which were already planned".5

In relation to additionality for PEF, the Cabinet Secretary said—

[The guidance] makes it clear that pupil equity funding must be used for additional purposes, not as a replacement. [...] Anybody who considers how to use the pupil equity funding must be mindful of the condition of grant and the guidance that goes with it.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], John Swinney, contrib. 180, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095952

The Committee wishes to highlight that many schools do not receive PEF and are undertaking valuable work to improve attainment using core funding. For completeness any system used to evaluate the impact of targeted Government funding must reflect progress in attainment achieved using core funding. An effective evaluation must reflect how attainment is improving, why and where the challenges, including funding levels, remain.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government's evaluation of its Attainment Scotland Fund.

The Committee recommends that as part of the next stage of this evaluation, the Scottish Government assess the extent to which PEF is used for additional purposes rather than for purposes that would be considered to be candidates to be covered from core funding.

In addition, the Committee recommends that the Scottish Government widens the evaluation to assess the separate impacts on the poverty-related attainment gap of programmes and interventions that are totally or primarily funded by:

the Pupil Equity Fund;

other aspects of the Attainment Scotland Fund; or

schools’ core budgets.

Challenges

Procurement

It is for headteachers to decide what PEF funded activities should take place in their schools. This has created challenges for headteachers. Graeme Young from Scouts Scotland told the Committee that good commissioning is very important. He suggested that the first step for headteachers is to work collaboratively with parents, young people and the wider community to identify needs and to "make and informed decision on what services are required". He continued—

Sometimes, that might mean purchasing a service, but sometimes it might mean working in partnership to develop a new service. Sometimes, too, it is just about better signposting to what is already out there and supporting what is already out there. There is a process element in all of this.

Education and Skills Committee 09 May 2018 [Draft], Graeme Young, contrib. 14, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11523&c=2091624

Andrea Bradley from the EIS welcomed the additional funding for schools but reported that schools, in the first year of PEF, were rushed into spending the money.2 In terms of commissioning new services from the third sector, John Butcher from North Lanarkshire Council said—

One of the fundamental issues around PEF that was never considered when it started was that, unlike social work, for example, which has procured services from the third sector for years and years and has relationships with Aberlour, Barnardo’s and whatever else, education has no history of procurement. There was an assumption when PEF came in that suddenly all our headteachers would know how to procure. That knowledge does not exist, so it will take a little bit of time to work our way through that.

Education and Skills Committee 09 May 2018 [Draft], John Butcher, contrib. 159, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11523&c=2091769

The Committee had heard evidence both from schools and third sector providers that on occasion procurement rules and procedures had prevented or delayed headteachers using PEF to purchase services. The Cabinet Secretary explained the split responsibilities for administering PEF monies. He said—

The decision-making power on how the money is spent rests with headteachers, as does the responsibility for how effectively it is spent. [...]

The public finance accountability—the judgement about whether the money has been spent on the purpose for which it was intended; that might be the best way to express it—rests with the local authority.

Education and Skills Committee 23 May 2018 [Draft], John Swinney, contrib. 169, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11556&c=2095941

Another impact of this process is that third sector providers now liaise directly with headteachers rather than local authorities as they might have done in the past. Finlay Laverty from the Prince's Trust said—