Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee

Report on Petition PE1817: End Conversion Therapy

Executive Summary

The Committee agrees that conversion practices are abhorrent and are not acceptable in Scotland. They should be banned. The Committee has heard that current protective legislation is insufficient to prevent these harms taking place.

The Committee agrees, based on the evidence taken, that the term “conversion therapy" or "practices” requires more clarity and should be explicitly defined in any proposed legislation. For that reason, it recommends that the definition used in the Report on Conversion Therapy by the UN Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, should be adopted for use in the legislation, namely "an umbrella term to describe interventions of a wide-ranging nature, all of which have in common the belief that a person's sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) can and should be changed. Such practices aim (or claim to aim) at changing people from gay, lesbian, or bisexual to heterosexual and from trans or gender diverse to cisgender".

The Committee notes from evidence that the majority of religious organisations we heard from are in favour of a ban on conversion practices. It agrees that legislation should not pose any restrictions on ordinary religious teaching or the right of people to take part in prayer or pastoral care to discuss, explore or come to terms with their identity in a non-judgmental and non-directive way. However, it heard evidence that most conversion practices take place within a religious setting including in the form of “talking therapy” which is used with the intention to “correct” sexuality or gender. The Committee believes and recommends that such practices should fall within a ban.

The Committee heard persuasive evidence that, for many survivors of conversion practices, their faith is part of their identity and they have felt forced to choose between faith and their sexual orientation or gender identity which can have a devastating impact. The Committee believes it is vital to involve religious and community leaders as a Bill progresses, and that education and awareness is crucial to promote acceptance of diversity. It recommends that the Scottish Government, when considering legislation, engages with a wide range of faith and belief organisations in order both to protect LGBT people and protect religious freedom. The Committee agrees that there is no conflict in protecting religious freedom and preventing harm by putting a ban in place.

The Committee is anxious to ensure that, in a similar way to legislation that exists to protect victims of domestic abuse or female genital mutilation, the definition makes it clear that consent to such practices can never be informed and should not be available as a defence to those undertaking conversion practices.

The Committee notes that the majority of healthcare bodies in the UK have signed the Memorandum of Understanding which prohibits conversion practices. However, it heard evidence that further clarity on the type of practice that is acceptable, and the type that is not, would be helpful for the medical profession and counselling services. Specifically, the Committee heard evidence that there is confusion and misunderstanding around the term “affirmative therapy” and it would be helpful for there to be a clarity provided to the medical profession, counselling services and wider society of what that is. The Committee recommends that a review of the development of the curriculum and training and further guidance on this issue would be helpful. Reference to how other countries in the world have addressed this within their legislation could also be helpful.

The Committee agrees that any proposals should not pose restrictions on parents or schools to provide a safe space for discussion and exploration but should prohibit harmful practices which attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity, including trans identity. The Committee agrees that “affirmative therapies” should be protected under any ban.

The Committee is satisfied that sufficient research and evidence is already available to conclude that the introduction of legislation is necessary. However, it is keen to emphasise the importance of positive and proactive engagement with diverse communities to accurately reflect the prevalence of conversion therapy and ensure protection can be provided to those who need it.

The Committee is anxious to ensure that time is not wasted gathering identical evidence from the same victims it heard from during its private evidence sessions. It is concerned that such evidence gathering may have the unintended consequence of re-traumatising victims. The Committee asks that the Scottish Government works with it to ensure that this exercise does not require to be repeated. It would be happy to seek consent from those individuals who engaged with the Committee so existing transcripts could be provided as evidence in a future consultation.

Having considered all the evidence presented to it, the Committee agrees that a ban on conversion practices should be fully comprehensive and cover sexual orientation and gender identity, including trans identities, for both adults and children in all settings without exception and include “consensual” conversion practices. The Committee recommends that any ban should also include a ban on advertising and promotion of conversion practices.

The Committee recognises that there are international human rights instruments that impose a duty on states to protect people from conversion practices and recommends that this framework is followed when drafting any legislation.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s commitment to banning conversion practices and the proposed work of the Expert Advisory Group. However, it has noted witnesses’ frustrations at the pace of progress and that more is not being done now to protect those at risk. The Committee notes that the Scottish Government plans to bring forward legislation before the end of 2023 if it considers that either UK, or other legislation, does not go far enough.

The Committee agrees that Scotland should not wait for UK legislation to be brought forward and considers that, within the powers available to the Scottish Government and Parliament, Scotland-specific legislation be brought forward as soon as possible. It recognises that work will be necessary to ensure the development of cross-border frameworks and calls on the UK Government to work with the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament on a ban.

The Committee heard strongly expressed views that legislation alone will not be sufficient to address conversion practices and that non-legislative measures will also be necessary to protect and support victims. The Committee heard a broad range of suggestions for support measures which could complement legislation.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government makes resources available to address gaps in support services for survivors and victims of conversion practices. The Committee acknowledges that many of the suggestions would take significant resource and planning but urges the Scottish Government to review these in detail.

The Committee heard strong views that prioritising a helpline, a whistle-blowing mechanism and a campaign to raise awareness including information in schools and more widely, would go a long way in ensuring victims know what conversion practices are, how to identify them and enable individuals to seek help. Consideration should also be given to providing a separate and distinct reporting mechanism for children.

The Committee found it helpful to hear international approaches to restricting and banning conversion practices and heard evidence that the Victoria legislation in Australia provides one of the best practice examples.

The Committee noted concerns around how enforcement of a ban could be effective and believes that consideration should be given to how this role could be fulfilled by a public body in ensuring investigation, enforcement and accountability is possible. The Committee notes that this enforcement role in Victoria, Australia is carried out by the Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission. The Committee urges the Scottish Government to consider this issue at this stage to ensure the correct mechanism for investigation and enforcement could be put in place.

In conclusion, the Committee is mindful of the volume of evidence that is already available, including the written and oral evidence it has received and considers it is important to bring forward legislation promptly. While noting the respective positions of the UK and Scottish Government and their commitments to bring forward legislation, the Committee is concerned that progress has been slow. It will therefore explore the merits of alternative options which might speed up the process. It would welcome discussions with the Scottish Government on the role of the Expert Advisory Group and the potential options of the Committee and the Scottish Government working together to bring forward a ban as quickly as possible.

The Committee would like to thank everyone who gave evidence to this inquiry but would particularly like to express its gratitude to the many individuals who took the time to share their experiences as victims and survivors of conversion practices. Many of these stories were harrowing to hear. The Committee recognises that this took enormous courage and this evidence was invaluable to our work.

Introduction

According to the definition used by many (see subsequent sections of this report), conversion therapy is an umbrella term for a therapeutic approach, or any model or individual viewpoint that demonstrates an assumption that any sexual orientation or gender identity is inherently preferable to any other, and which attempts to bring about a change of sexual orientation or gender identity or seeks to suppress an individual’s expression of sexual orientation or gender identity on that basis. The terms "conversion therapy" and "conversion practices" are used interchangeably in this report to reflect wording used by witnesses. However, the Committee's preference is to use the term"conversion practices".

PE1817: End Conversion Therapy was lodged in August 2020. It calls on the Scottish Parliament “to urge the Scottish Government to ban the provision or promotion of LGBT+ conversion therapy in Scotland”.

The UK Government made a commitment in July 2018 to “eradicate the abhorrent practice of conversion therapy”. In its letter of 17 July 2020 to the session 5 Public Petitions Committee, the Scottish Government stated that it “fully supports moves by the UK Government to end conversion therapy”. The petitioners state that because health and criminal justice are devolved, the Scottish Government has the power to ban LGBT+ (lesbian, gay, bi-sexual,trans gender) conversion therapy in Scotland.

In its Programme for Government 2021-22 (7 September 2021) the Scottish Government stated its commitment to banning conversion therapy and that it would bring forward “legislation that is as comprehensive as possible within devolved powers by the end of 2023, if UK Government proposals do not go far enough”.

The Public Petitions Committee in session 5 referred the petition to the predecessor Equalities and Human Rights Committee. That Committee received further written evidence jointly from Stonewall Scotland, Equality Network, Scottish Trans Alliance and LGBT Youth Scotland and agreed to keep the petition open and refer it to its successor committee in this parliamentary session.

In May 2021, the UK Government announced measures would be brought forward to ban conversion therapy in the Queen’s speech. This was followed by a commitment to launch a consultation and then introduce legislation banning conversion therapy in the UK.

The UK Government launched its consultation on banning conversion therapy on 29 October 2021. It recently announced an extension to that consultation to 4 February 2022. The proposals are for England and Wales only and the consultation states that the UK Government has liaised closely with the devolved administrations. The intention is to prepare draft legislation by spring 2022.

The Committee recognises that whilst much of the legislation needed to ban conversion practices is devolved, there are aspects which are reserved. The Committee has taken cognisance of this in its deliberations and will continue to do so. It has also considered and will continue to consider the provisions within the UK Government proposals and the extent to which they address the issues that the Committee has heard in its evidence.

Background to the Petition

The petitioners are calling for a ban on LGBT+ conversion therapy in Scotland to help bring an end to conversion practices. They refer to research from the 2018 Faith & Sexuality Survey from the Ozanne Foundation which found that attempts to change sexual orientation results in harm. Of those who had experience of sexual orientation conversion therapy it found:

almost two-thirds, 58.8%, had "suffered from mental health issues", of which

nearly a third, 32.4%, had attempted suicide

68.7% said they had suicidal thoughts

40.2% had self-harmed

24.6% suffered from eating disorders

The petitioners stated they are frustrated with the UK Government’s current progress as it had previously made a commitment to ban conversion therapy in 2018.

Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee's consideration

At its first meeting on 23 June 2021, the Session 6 Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee agreed to undertake an Inquiry on the Petition to End Conversion Therapy in Scotland.

The Committee undertook a call for written evidence between 6 July and 13 August 2021. It received around 1400 submissions of which the majority were received from individuals in support of the petition. Around 76 submissions were received from organisations.

Published submissions are available on Citizen Space and are also accessible via the Committee’s web page. A summary of the written submissions from organisations was included in the meeting papers for the Committee’s first evidence session on 7 September 2021.

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) also produced a briefing which is available online and which can be accessed here.

The Committee began taking oral evidence on 7 September 2021 when it heard from the Petitioners:

Tristan Gray and Blair Anderson, on behalf of End Conversion Therapy Scotland.

On 14 September 2021, the Committee heard from LGBT+ groups:

Megan Snedden, Policy and Campaigns Manager, Stonewall Scotland

Dr Rebecca Crowther, Policy Co-ordinator, Equality Network

Vic Valentine, Manager, Scottish Trans Alliance

Paul Daly, Policy and Research Manager, LGBT Youth Scotland.

On 21 September 2021,the Committee heard from human rights organisations:

John Wilkes, Head of Scotland, Equality and Human Rights Commission

Barbara Bolton, Head of Legal and Policy, Scottish Human Rights Commission

Dr Igi Moon, Chair, Memorandum of Understanding Coalition Against Conversion Therapy

Jen Ang, Director of Development and Policy, JustRight Scotland.

On 2 November 2021, the Committee heard from faith organisations who support the petition:

Rici Marshall Cross, Clerk of South Edinburgh Local Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, Quakers in Scotland

Jayne Ozanne, Director of the Ozanne Foundation, Chair of the Ban Conversion Therapy Coalition

Rev Elder Maxwell Reay, member of the Council of Elders of Metropolitan Community Churches, NHS Health Care Chaplain

Rev Fiona Bennett, minister of the Augustine United URC and Moderator Elect of the General Assembly, United Reformed Church.

On 16 November 2021, the Committee took evidence from three separate panels. Firstly, it heard from organisations who had expressed concerns about the action called for in the petition:

Peter Lynas, UK Director, Evangelical Alliance

Piers Shepherd, Senior Researcher, Family Education Trust

Dr John Greenall, Associate Chief Executive Officer, Christian Medical Fellowship

Anthony Horan, Director, Catholic Parliamentary Office.

Secondly, it heard reflections on the effect of legislation in the State of Victoria in Australia from:

Nathan Despott, Steering Committee, Brave Network and Honorary Research Fellow, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Dr Timothy Jones, Associate Professor, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Finally, the Committee heard from academics:

Dr Christine Ryan, senior legal adviser to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief

Dr Adam Jowett, Associate Head, School of Psychological, Social & Behavioural Sciences, Coventry University and lead author of UK government commissioned research into conversion therapy.

The Scottish Government was unable to provide a representative to give oral evidence to the Committee within its timetable but offered to write to the Committee with an update. The written update was provided to the Committee by the Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government on 17 November 2021. The response is set out in further detail in this report.

The Committee also wrote to the UK Government seeking an update on its progress. The Minister for Equalities Mike Freer replied on 9 December 2021 setting out the UK Government’s proposals which are set out in further detail in this report.

Engagement

In addition to taking formal oral and written evidence, the Committee held private informal sessions with survivors of conversion therapy. These sessions were facilitated in partnership with organisations who support LGBT+ people including survivors of conversion therapy and provided some of the most impactful, powerful and persuasive evidence the Committee heard during its scrutiny.

The individuals who engaged with these sessions have given their consent for the notes taken to be published on our webpage and these are available here. One of the key messages emphasised by stakeholders we heard from, was that survivors of conversion therapy are the experts and should be at the forefront of any decision-making process by the Scottish Government on the way forward.

Key issues in the Committee's consideration of the Petition

Definition of conversion therapy/practices

The Committee heard strong support for the petition to ban conversion practices. However, many witnesses said that more clarity was needed in relation to what should be included in the definition of conversion therapy/practices in any forthcoming legislation.

Tristan Gray said that conversion therapy has “the directed intent to change someone. It is a concerted effort to change that to, what is considered to be the correct way to be” He described it as a “broad term for psychological conditioning that seeks to force people to change or suppress their sexual orientation, to repress or reduce their sexual attraction or behaviours, or to change their gender identity to match the sex that they were assigned at birth".i

Many witnesses referred to existing definitions as a starting point:-

Memorandum of Understanding on conversion therapy, which focuses on the medical profession and defines conversion therapy as:

an umbrella term for a therapeutic approach, or any model or individual viewpoint that demonstrates an assumption that any sexual orientation or gender identity is inherently preferable to any other, and which attempts to bring about a change of sexual orientation or gender identity or seeks to suppress an individual’s expression of sexual orientation or gender identity on that basis.ii

Report on Conversion Therapy by the UN Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity who define Conversion Therapy as:

an umbrella term to describe interventions of a wide-ranging nature, all of which have in common the belief that a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) can and should be changed. Such practices aim (or claim to aim) at changing people from gay, lesbian or bisexual to heterosexual and from trans or gender diverse to cisgender.iii

Vic Valentine of the Scottish Trans Alliance referred to the legislation passed in Victoria, agreeing that the practice must be clearly defined “so that people know what they should and should not do”. They described conversion therapy as “an approach that has a predetermined outcome for what it wants to do to an LGBT+ person; it wants to change or suppress their sexual orientation or gender identity”.iv

This was a view shared by Megan Snedden of Stonewall Scotland. She told us “A key defining feature of conversion therapy is that it has a predetermined, one-directional outcome: it tries to change or suppress someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity".v

Barbara Bolton of the Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) referred to comments by the UN Special Rapporteur on Religion and Belief, who has suggested that “in order to be sufficient in terms of safeguards for freedom of religion and expression, the definition of conversion practices should include that a specific person, or class of persons, is targeted on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity, for the purpose of changing or suppressing their sexual orientation or gender identity”.vi

It is important, John Wilkes of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) told us, to include both sexual orientation and gender identity in the ban. He said “Those two things are not the same ... so in drawing up definitions we need to ensure that we reflect that properly".vii

Conversion therapy was described by Jen Ang of JustRight Scotland as a practice that was founded on the belief that certain sexual orientations or gender identities are wrong and require correction. She said “It is a form of violence or discrimination committed against individuals because of their sexual orientation or gender identity and, on that basis, it is a violation of the international human rights legal framework".viii

However, Piers Shepherd of the Family Education Trust held a contrary view. He told us “There is no consistent definition of what conversion therapy is”. He expressed concern that “a broadly scoped ban would criminalise anything other than immediate acceptance, encouragement and celebration of a child’s sexual or gender identity, regardless of their age".ix

Concerns were also expressed by Anthony Horan of the Catholic Parliamentary Office of the Bishops’ Conference of Scotland. “What is of genuine concern is that some of that day to day practice of the church will be consumed by a sweeping definition of conversion therapy… We want to get to a place where people are protected from harm, if the law does not do so while at the same time protecting those who wish to pray and follow their religion and those who voluntarily seek spiritual support”.x

In written evidence, The Bishops’ Conference of Scotland stated it would not oppose the banning of such practices. They said:

It is important to recognise that there are many people with same-sex orientation who wish to live their lives in harmony with the teachings of the Church. Of their own volition, with informed consent and free from any coercion, they may ask for help to live according to their beliefs and values. It is vital that any legislation protects them and those who support them. Action which does not seek to change or suppress a person’ sexual orientation, should fall well outside any definition of conversion therapy.xi

Peter Lynas of the Evangelical Alliance supported the Westminster approach of using two tests in defining conversion therapy, the first on coercion and the second on choice and consent. He told us he did not wish to face a situation where potentially he could counsel and pray with a heterosexual person without risk but come up against a ban if he chose to pray with a same sex attracted person. He told us he would like to see a clear clause on coercion and have a consent clause “to allow people to choose these treatments, even if others disagree".xii

Dr Greenall of Christian Medical Fellowship told us in relation to definition “At one extreme is severe physical and sexual violence which is abhorrent. “Harm” when it is more broadly defined, needs to be distinguished from legitimate freedoms and it needs to be based on evidence. We would want the Committee to examine the definition, particularly when it comes to what constitutes harm and the evidence for that".xiii

The Committee agrees that conversion practices are abhorrent and are not acceptable in Scotland. They should be banned. The Committee has heard that current protective legislation is insufficient to prevent these harms taking place.

The Committee agrees, based on the evidence taken, that the term “conversion therapy" or "practices” requires more clarity and should be explicitly defined in any proposed legislation. For that reason, it recommends that the definition used in the Report on Conversion Therapy by the UN Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, should be adopted for use in the legislation, namely "an umbrella term to describe interventions of a wide-ranging nature, all of which have in common the belief that a person's sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) can and should be changed. Such practices aim (or claim to aim) at changing people from gay, lesbian, or bisexual to heterosexual and from trans or gender diverse to cisgender".iii

Religious freedom

The Committee heard evidence that many conversion practices take place in religious settings with support of religious leaders. While it heard that the majority of religious groups support a ban on these practices, some faith-based organisations are concerned that a ban could have an impact on the non-coercive support they provide, for example, through prayer or pastoral care. They raised concerns that religious leaders could be criminalised.

Several written submissions, in full support of the petition, referenced statements made by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Dr Ahmed Shaheed, on how international human rights law presents no conflict between the right to freedom of religion or belief and the obligation of the state to protect the life, dignity, health and equality of LGBT+ persons.

The Joint Response from Equality Network, Scottish Trans Alliance, Stonewall and LGBT Youth Scotland said:

The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief stated in April 2021 that ‘international human rights law is clear that the right to freedom of religion or belief does not limit the state’s obligation to protect the life, dignity, health and equality of LGBT+ persons” and that “banning such discredited, ineffective, and unsafe practices that misguidedly try to change or suppress people’s sexual orientation and gender is not a violation of the right to freedom of religion or belief under international law.i

This was also the view of Jen Ang of JustRight Scotland who said that ordinary religious teaching and appropriate pastoral care would not be prohibited and for some people it is in a religious setting where they would best be able to access a non-judgemental and supportive environment in which to explore their gender identity and sexual orientation. She believes that it is important to involve religious and community leaders in the process of crafting any legislation and for any guidance accompanying it.

Tristan Gray considered that the “freedom to pray for others and have faith should not be impacted by [any] legislation” However, he argued this is distinct from circumstances in which people are made to take part in prayer “to correct their sexuality or gender identity…[which] crosses the line from freedom of religion into an abusive situation".ii

Others acknowledged concerns around potential impacts on religious freedom and the right to prayer, whilst also reflecting on the negative impact on individuals subjected to conversion therapy. Dr Rebecca Crowther of Equality Network said:

We are very happy about and open to people praying with and supporting other people pastorally…However, a line needs to be drawn where that treads into coercive control and is practised “upon” people and in a directive, agenda-led way to change that person.iii

Barbara Bolton referenced the guidance from the special rapporteur on religion and belief and said:

It comes down to the way that legislation is crafted. Germany and Victoria have managed to come up with wording that covers all conversion therapy but does not preclude ordinary religious practice or pastoral care… The legislation has to be crafted so that it covers what needs to be prohibited in order to protect LGBT+ people at the same time as protecting religious freedom. I think that balance can be found.iv

John Wilkes of EHRC, identified that there are LGBT+ people who “wish to adhere to the tenets of their faith”. On this basis, he said:

The law should be drawn up such that it allows support from faith leaders and spiritual leaders – support that is not intent on changing a person’s identity but can help them in in how they live their life within the rules of their religious faith or belief. To us, that is the key dividing line.v

Jayne Ozanne of the Ozanne Foundation told us that research clearly showed that the vast majority of conversion practices occur in religious settings and if a ban is to protect people, it must impact on certain harmful religious practices.

We have recommended that there must be tests to determine whether a practice is an example of conversion therapy. That practice needs to be directed at a group of individuals and is not just a general practice, it needs to have a predetermined purpose of seeking to change, cure or suppress someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

She said “the sort of prayer that creates an open and safe place into which people can go and where any outcome is acceptable and right is good and should be encouraged. However, when there is a pre-determined purpose I think that must be banned".vi

The Committee heard from witnesses that many major denominations including the Church of England and the Methodist church and other groups such as Baptist ministers, the Hindu Council UK and the Buddhist Dhamma Centre had called for a ban but they were seeking a clear indication from governments about what is acceptable and what is not. “Once we have that” Jayne Ozanne told us “we can work within their religious communities to end it".vii

Jayne Ozanne views conversion therapy as a violation of Articles 3 and 8 of ECHR and said states were under a positive legal obligation to provide an adequate framework of protection for LGBT+ people. She did not accept a ban may breach articles 9 and 10 (freedom of religion and belief and freedom of speech). She told us both the UN convention and the ECHR make statements and put in place limitations where there is clear evidence of harm. “Those who want to continue the use of conversion therapy have never admitted harm. I would ask you to push them on whether they will admit that thousands of testimonies in qualitative research as well as the quantitative research show that harm has been done".viii

Rev Elder Maxwell Reay agreed and said he worked with people of every faith and no faith to support their spiritual needs and was able to provide support safely and securely without putting views across. “I work in that way every day and it raises no concerns in relation to the right of religious freedom".vii

However, some organisations we heard from were not satisfied that competing rights could be so readily balanced. Many sought an exception for prayer and pastoral care particularly where this was sought by individuals. In their written submission, the Christian Medical Fellowship said that “There is no hiding from the fact that historic, biblical and Christian beliefs are out of step with contemporary notions of sexuality and gender”. However, “We ask the Scottish Government to distinguish carefully between abhorrent and coercive practices, that should be banned, and the pastoral care, counsel and prayer that is helping many LGBT+ people, that should lie outside the scope of a ban".x

In its written submission, the Evangelical Alliance said it recognised that the church had played a role in causing harm, hurt and stigma towards individuals because of their sexual orientation and did not shy away from that. However, a ban may “infringe upon civil liberty” In oral evidence Peter Lynas said “We absolutely support a ban on coercive and abusive behaviours” but “there is a need to safeguard spiritual support for those who choose it. He said “We are aware that Westminster has recently released its consultation while allowing prayer and pastoral support. It is clear that people can consent to practices that others might well disagree with".xi

He went on “I do not want special protection and I do not want special rights to do something that is illegal and wrong. I want the balance to find and be able to pray with people and to offer the spiritual support that people are asking for, consenting to and making a free choice to enter into".xii

The Family Education Trust said “while we recognise that it may sometimes be necessary to protect people from “quack therapies” we believe that the proposed conversion therapy ban would deal a terrible blow to the freedom and autonomy of the individual as well as to freedom of choice, freedom of speech and freedom of religion".xiii

Piers Shepherd had particular concerns about the potential impact on children of a ban. He said “The law needs to protect the right of parents to bring up their children in a way that is consistent with their moral and religious beliefs. Parents must not be reluctant to discuss issues around sexuality and gender with their children for fear of being accused of conversion therapy".xiv

The Committee acknowledges the view expressed by Piers Shepherd. However, it believes there is a clear distinction to be made between parents having the right to bring up their children in line with their morals and values and having the directed intent to change their child's sexuality, or gender identity. Some of the survivors we heard from told how they experienced conversion practices from within the family. In the Committee's view, that is a clear crossing of a line.

Dr Christine Ryan, External Office of the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, noted that the regulation of conversion practices in religious settings can be “very challenging”. She added, however, “the right to freedom of religion or belief under international law is not a barrier to ending conversion practices. In some situations, the harms that are caused by conversion practices justify infringing on the freedom of religion or belief of some, but any constraint on that right must be capable of being justified as necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory".xv

The Committee notes the evidence that the majority of religious organisations we heard from are in favour of a ban on conversion practices and agrees that legislation should not pose any restrictions on ordinary religious teaching or the right of people to take part in prayer or pastoral care to discuss, explore or come to terms with their identity in a non-judgmental and non-directive way. However, it heard evidence that most conversion practices take place within a religious setting including in the form of “talking therapy” which is used with the intention to “correct” sexuality or gender. The Committee believes and recommends that such practices should fall within a ban.

The Committee heard persuasive evidence that, for many survivors of conversion practices, their faith is part of their identity and they have felt forced to choose between faith and their sexual orientation or gender identity which can have a devastating impact. The Committee believes it is vital to involve religious and community leaders as a Bill progresses, and that education and awareness is crucial to promote acceptance of diversity. It recommends that the Scottish Government, when considering legislation, engages with a wide range of faith and belief organisations in order both to protect LGBT people and protect religious freedom. The Committee agrees that there is no conflict in protecting religious freedom and preventing harm by putting a ban in place.

The Committee is anxious to ensure that, in a similar way to legislation that exists to protect victims of domestic abuse or female genital mutilation, the definition makes it clear that consent to such practices can never be informed and should not be available as a defence to those undertaking conversion practices.

The Medical Profession

The Committee heard that some faith-based organisations and gender critical organisations are concerned about the inclusion of gender identity conversion therapy and that medical practitioners may be criminalised if they do not ‘affirm’ a young person’s gender identity.

In their written submission, The Memorandum of Understanding coalition said that any legislation needs to strike a careful balance so as not to expose genuine practitioners to the risk of criminal prosecution in supporting individuals.

Blair Anderson told the Committee that the majority of conversion therapy cases occur in religious and family rather than medical settings and advised that almost all healthcare bodies in the UK had co-signed the Memorandum of Understanding that expressly denounces conversion therapy.

However, he said that he was aware of a limited number of instances and would wish to see a ban on psychiatry where there is an intention to change someone’s sexuality or gender identity. This should not include “affirmative therapies” where individuals are seeking support and a space to explore their identity. He told us “We do not foresee a significant tightening of regulations for people who are practising psychiatry or counselling".i

He added “Conversion therapy is not a form of therapy. It is not a positive, therapeutic or counselling treatment... - for want of a better word it is often seen as a form of torture” and “people cannot consent to being abused or tortured. It is not possible for a person to change their sexuality or gender identity, it cannot work. Anything that comes from that process is based on trauma, suppression and the denial of fundamental and unchangeable aspects of who someone is – their sexuality and their gender identity".

Affirmative therapies

The Committee heard that the term “affirmative therapy” was often misunderstood within this context. Vic Valentine of the Scottish Trans Alliance told us “[People] rush to the assumption that if someone were to approach a medical professional and say “I think I might be trans” the professional would be expected to respond by saying “Yes, you absolutely are. Fabulous!".i

They explained “By “affirmation” we mean that if someone has questions or concerns about who they are, a medical professional will respond to them with care and empathy and tell them it is okay that they feel that way and they can explore it together and find out what it means for the person. It does not necessarily mean that the professional points someone in a pro-transition or anti-transition direction. It is about holding the space for the individual to find out who they are and they can come to that decision themselves".i

This view was shared by Barbara Bolton “The Memorandum of Understanding notes that anyone who goes into the space of providing such therapy needs to have such qualifications and understanding and enter the space without bias or pre-determined outcome. What is not required is that they affirm and continue down that path. There must be room for exploration".iii

She told us that “The independent expert on sexual orientation and gender identity recommends that regardless of whether there is a ban on conversion therapy, states should adopt and facilitate healthcare and other services related to exploration free development and/or affirmation of sexual orientation and gender identity. Any ban should not cut across them. The key is that they are non-judgmental and non-directive".iv

According to Dr Moon, more guidance would be beneficial on affirmative therapy and to “upgrade our thinking in the training of therapists, psychologists and doctors. Dr Moon said “Effort needs to be made to ensure there is more intersectional thinking. Affirmative therapy is about offering flexibility of thinking it does not mean focusing on gender”..and that “We need to grab hold of this moment to stop the rather horrible language about affirmative therapy assigning itself only to gender, because it does not. Affirmative therapy is the way that therapists work flexibly with clients—children and adults—to ensure that they are in a safe space with an accredited registered therapist, who has probably gone through as much training as is on offer, although I think that that needs to improve".v

Dr Christine Ryan of the External Office of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief said “There is an understanding that affirmative care is about providing the space for somebody to have an open discussion with their religious leader, therapist, psychiatrist, or healthcare provider. I would include that in the legislation. Rather than provide blanket exemptions for conversion practices in religious settings you can include safeguards to ensure that there are no unnecessary infringements on freedom of religion or belief".

She suggested an exemption could make it clear that individuals cannot be prohibited from discussing sexuality or gender with their faith leaders or with their family or healthcare professionals. She told us that under international law parents have the right to raise their children in accordance with their religious beliefs and have the right to seek counsel about their sexuality and explained that the state cannot compel religious leaders to change their beliefs or teachings on discriminatory matters.vi

In its written submission, The Christian Medical Fellowship took a different view “The petitioners propose that only affirmative therapies should be allowed under a ban. They appear unwilling to recognise that some people struggle with unwanted same sex attraction or gender identity issues. They also discount the growing number of people wishing to de-transition, a phenomenon that at the very least mandates careful study and a moratorium on affirmation only approaches".vii

Consent

The issue of consent was also explored by the Committee, particularly in respect of those who may feel uncomfortable with their sexuality or gender identity. Blair Anderson explained “It can be difficult to draw the line between what is consensual and what is not. If someone says they are uncomfortable, but they have been brought up in a religious environment where they have been taught since childhood that they are broken and need to be fixed, that is not truly consensual".i

On this point, the Committee heard that to understand “consent” in this context requires an understanding of how coercion works in the context of domestic abuse. Jayne Ozanne told us that case law does not allow for consent, even informed consent where there is an imbalance of power and where vulnerable people will be put at risk. “The law around female genital mutilation, forced marriage and domestic abuse does not allow for consent"ii she said. Other witnesses referenced to FGM and domestic abuse legislation as containing relevant provisions.

Dr Jowett agreed “The people we spoke to said they had undergone conversion therapy voluntarily but that was under the guidance of people in positions of trust and authority and under immense internalised social pressure and fear that they would be rejected by their community. A ban that would allow consensual conversion therapy would not protect the people we spoke to".iii

Survivors of conversion therapy who engaged with the Committee during its private sessions echoed this point. Many of the individuals who shared their experiences told us that they willingly engaged in or actively sought out conversion therapy as adults as a result of deep-rooted feelings that there was something wrong with them and that, without change, they would not be accepted within their church or communities. Many described themselves as vulnerable at that time and not having the capacity to give informed consent.

The weight of evidence suggests that “consenting” to conversion therapy often occurs in circumstances where individuals are part of a community or brought up to believe that being LGBT is wrong and therefore consent is not legitimate or informed.

On the issue of informed consent, the Committee heard contrary views. The Family Education Trust said they “do not believe that a person who may feel trapped in a particular sexual lifestyle should be forbidden by law from seeking counselling or other forms of help should they desire it. Nor should it be a crime to offer such counselling, whether it be of a religious nature or of the more clinical variety".iv

Gender identity

Other witnesses expressed concerns about how a ban may affect children and young people who are confused about their gender. We heard that a ban may have a chilling effect on parents who seek to help a child with gender dysphoria and that any exploration of issues contributing to gender dysphoria could be deemed conversion therapy potentially leaving the child or young person unable to receive the help they need.

In their written submission the EHRC stated “Proposals should not be designed to police how parents or guardians respond if their child identifies as LGBTI+ but rather to prohibit harmful practices that attempt to change or suppress a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity".i

Dr Greenall questioned whether the law would cover those who “have been pushed towards an LGBT identity as well as away from it?” He said as a medic and paediatrician he felt that the category of gender identity conversion therapy is very broad and there were concerns that open and frank discussions could not take place on gender for the fear of being labelled transphobic. He said many children “outgrew” their trans identities and that children need time and space to explore and talk.ii

Piers Shepherd from the Family Education Trust told us “The specific inclusion of gender identity and the potential impact on children and young people is another thing we are very worried about.” He referenced the Care Quality Commission’s report at the Tavistock gender identity service which was highly critical of the service’s failure to assess the competency and capacity of young people receiving treatment for gender dysphoria. “We feel a ban would make such situations more difficult".iii

He went on “Gender dysphoria in children is often fleeting… We are very worried. We feel that anything that is not immediately affirming and encouraging towards a particular sexual orientation is going to be criminalised” and suggested evidence should be sought from people who “feel they have benefitted”. Dr Greenall endorsed this view. He questioned the robustness of evidence and whether evidence had been considered of those “who had had a positive experience”. He called for all evidence to be fully considered particularly in relation to those who had de-transitioned. “I feel that the evidence is not robust enough to base such significant decisions on” he said.iv

He also supported a distinction being made between adults and children and believed that for an adult it is voluntary if they choose to seek out a particular type of counselling or spiritual help. “We believe that parents have the right to bring up their children according to the moral beliefs that they have [and] were a ban such as this passed it would make it a lot more difficult for parents … to get help for a gender dysphoric child".v

The Committee notes that the majority of healthcare bodies in the UK have signed the Memorandum of Understanding which prohibits conversion practices. However, it heard evidence that further clarity on the type of practice that is acceptable and the type that is not would be helpful for the medical profession and counselling services. Specifically, the Committee heard evidence that there is confusion and misunderstanding around the term “affirmative therapy” and it would be helpful for there to be a clarity provided to the medical profession, counselling services and wider society of what that is. The Committee recommends that a review of the development of the curriculum and training and further guidance on this issue would be helpful. Reference to how other countries in the world have addressed this within their legislation could also be helpful.

The Committee agrees that any proposals should not pose restrictions on parents or schools to provide a safe space for discussion and exploration but should prohibit harmful practices which attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity, including trans identities. The Committee agrees that “affirmative therapies” should be protected under any ban.

Evidence of conversion therapy/practices

The Committee heard that conversion therapy can take place in a number of settings. While the evidence suggests that the majority of practices are conducted by faith organisations, others reported conduct by a parent or person from their community or by a healthcare provider. Most of the evidence heard was concentrated on changing sexual orientation. The Committee took less evidence relating to gender identity change. However, where evidence was given (by individuals), a similar approach was adopted.

Some written submissions received queried the prevalence of conversion therapy, while others suggested that more research may be required to target support to survivors or those at risk.

Dr Crowther of Equality Network said that survivors’ voices must be put at the forefront regardless of faith. “You need to hear about their experience within their own community and how such practices work within them”.i She said “One thing I would hate to see here is no engagement with cultural sensitivities or diverse communities because all that would do is drive the practice further underground, further alienating and marginalising people and causing further harm. If people do not understand conversion therapy or if they are not aware of its implications or believe it is the right thing to do it will just be more hidden and there will be more stigma around it".ii

Paul Daly agreed and explained that successful and meaningful communication had been carried out with communities on other legislation such as female genital mutilation and that revisiting those approaches could be beneficial when reaching out to communities.i

Dr Moon was clear that no further research was required:

I do not know how much more research we want. It is happening, we know that it is happening, and we have evidence that it is happening. We need to stop it and we have an opportunity to do that.

To me, if any young person who is born today reaches 10 or 15 and has the opportunity to live in the world in a safe way because of what we have done, that will be one of the greatest statements of freedom that we could possibly have. That is why we are here. That young person does not need to know who we are; they need to know that we have created safety and security for their life. With all due respect, there is a limit to how much research and how many consultations and meetings we can have. It is an abhorrent practice and it needs to stop. We have the opportunity to stop it, so let us do it".iv

The Committee is satisfied that sufficient research and evidence is already available to conclude that the introduction of legislation is necessary. However, it is keen to emphasise the importance of positive and proactive engagement with diverse communities to accurately reflect the prevalence of conversion therapy and ensure protection can be provided to those who need it.

The Committee is anxious to ensure that time is not wasted gathering identical evidence from the same victims it heard from during its private evidence sessions. It is concerned that such evidence gathering may have the unintended consequence of re-traumatising victims. The Committee asks that the Scottish Government works with it to ensure that this exercise does not require to be repeated. It would be happy to seek consent from those individuals who engaged with the Committee so existing transcripts could be used as evidence in a future consultation.

Legislative ban - what should it cover?

The UK Government has published a consultation on proposals to ban conversion therapy for England and Wales. It plans to publish draft legislation in Spring 2022. The Scottish Government has indicated that if it considers the UK Government proposals do not go far enough it will bring forward its own legislation that is as comprehensive as possible within devolved powers by the end of 2023.

The Scottish Government has stated that it will explore what legislative and non-legislative measures can be taken to best protect and support those who need it, whilst ensuring that freedoms of speech, religion and belief are safeguarded.

The Scottish Government has started work to establish an Expert Advisory Group on these issues. That group is expected to start its work in Spring 2022.

Much of what a legislative ban would cover will be dependent on the definition of conversion therapy. The Committee heard that some of the more extreme practices of conversion therapy are already unlawful. Other practices, however, can be subtle or hidden.

John Wilkes told us “there are some elements of certain types of conversion therapy, such as corrective rape, that could easily be covered under existing legislation, but there may be other areas of conversion therapy that will not be so easily covered by that legislation. It is about filling the gap and ensuring that there are no gaps in protection for people who experience conversion therapy, which […] can include a whole range of things. There may be elements of the law – not only the criminal law but civil law, in terms of the regulation or further regulation of professional bodies - that might need to be looked at to fill those gaps".i

Blair Anderson stressed the importance that any ban would need to be “fully comprehensive”. He said “that includes covering sexuality and gender, and it includes forced conversion therapy, so-called consensual conversion therapy and any attempt to change or suppress someone’s sexuality or gender identity […] without loopholes or exemptions".ii Blair Anderson said the ban should cover non-affirmative forms of therapy for trans people so trans young people are protected. This was a view supported by others including Stonewall. In addition to legislation many witnesses also stressed the importance that non-legislative measures were also put in place.

This view was shared by Barbara Bolton who considered that legislation could have a strong deterrent effect which would have particular impact on conduct occurring behind closed doors. She told us that if a ban was combined with raising awareness and a public education campaign, the overall impact could be very positive and “challenge the undermining of the dignity of LGBT+ people, which can make them more vulnerable to discrimination and violence".iii

Jen Ang said that there is a gap in the law as it stands and the number of people experiencing harmful practices and that action needs to be taken. Actions such as rape and physical assault are already illegal but other harmful behaviour is not being captured and prosecuted because it is not picked up through the frameworks we have.

She told us that legislation to ban conversion therapy could complement existing legislation in a similar way as the package of support that is geared towards combating gender-based violence sits alongside prosecution of other criminal offences. She voiced support for a ban that would include criminalisation of an offence. “The harm occurs through people engaging with someone […] in order to try to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. Such action is very difficult to pursue. Indeed, it is not possible to pursue it in all contexts. That is the gap".iv

Dr Jowett explained why it is important to include sexual orientation and gender identity in a ban. He said “Conversion therapists often claim that gay people have what they call gender identity deficits and that transgender people have a more severe version of these deficits. Therefore, conversion therapists often do not make the distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, and conversion efforts that are aimed at transgender people are often based on the same unscientific claims and theories, apply the same methods and are often conducted by the same groups and people".v

In its written submission, the EHRC said that practices causing the most harm should attract the most robust interventions. In terms of rape for example, or ‘corrective rape’ in this context, they said it may be appropriate to modify the penalties to take account of conversion therapy.vi

The SHRC submission set out the international human rights framework in detail, including those international human rights instruments that impose a duty on states to take positive steps to protect LGBT people.vii The Committee also received a few written submissions that support people who are “formerly LGBT” or have “unwanted same-sex attraction or gender identity confusion”.

The LGBT Group said that any exemption for those who consented to conversion practices would leave many at risk of physical and psychological harm.viii

The Committee therefore heard a range of suggestions of what could be considered within the legislation. These included that:

It must cover all practices, with or without consent, and in different settings including (home, medical, religious)

It must cover sexual orientation and gender identity

LGBT people of all ages must be protected, including children

It must cover a route to criminal conviction where conversion therapy is taken outside the UK

It must include redress and compensation for survivors.

The Committee heard how important the messaging was around the issue. Blair Anderson said one of the key benefits of legislation would be to provide clarity and to “explicitly state that the Parliament and Scotland as a whole condemns and prohibits conversion therapy. That statement would be immensely useful to people who are going through it and have tangible benefits for survivors".ix

Having considered all the evidence presented to it, the Committee agrees that a ban on conversion practices should be fully comprehensive and cover sexual orientation and gender identity, including trans identities, for both adults and children in all settings without exception and include “consensual” conversion practices. The Committee recommends that any ban would also include a ban on advertising and promotion of conversion practices.

The Committee recognises that there are international human rights instruments that impose a duty on states to protect people from conversion therapy and recommends that this framework is followed when drafting any legislation.

UK wide or Scottish approach

The UK Government is consulting on proposals for a ban on conversion therapy, but these apply to England and Wales only. The UK Government wrote to the Committee on 9 December 2021 to provide an update.

In its proposals, the UK Government has considered the evidence, including additional commissioned research, and identified gaps in the law that allow conversion therapy to continue. It has developed a package of civil and criminal measures.

The proposals are universal in that they will apply to any sexual orientation or gender identity. While the proposed ban is meant to address conversion therapy carried out on LGBT people, it will provide everyone with the same protection.

The UK Government states the proposals will protect freedom of speech, freedom of belief and privacy while ending the practice of conversion therapy. It states proposals must strike a balance with competing rights under the Human Rights Act 1998 and European Convention on Human Rights.

The proposals are to:

Target physical acts conducted in the name of conversion therapy by legislating to ensure this motivation for violence is considered by the judge as a potential aggravating factor upon sentencing

Target talking conversion therapy with a new criminal offence where it is committed against under 18s under any circumstance, or committed against those aged 18 or over who have not given their informed consent or due to their vulnerability are unable to do so, and

Produce a holistic package of measures such as a Conversion Therapy Protection Order, new support for victims, restricting promotion, removing profit streams and strengthening the case for disqualification from holding a senior role in a charity.

In addition to the consultation, the UK Government published:

The prevalence of conversion therapy in the UK which weighted the data from the 2017 National LGBT survey. The results showed that the weighted results for the survey questions on conversion therapy were not markedly different from the unweighted results.

Conversion therapy: an evidence assessment and qualitative study which is independent research from Coventry University. Professor Adam Jowett was the lead author.

An assessment of the evidence on conversion therapy for sexual orientation and gender identity which is a report by the UK Government’s Equality Office. It supplements the commissioned research by Coventry University and aims to distinguish between evidence on conversion therapy for sexual orientation and for gender identity.

On 17 November 2021, the Scottish Government wrote to the Committee. It states that it will bring forward legislation by the end of 2023 if the UK Government proposals do not go far enough. The Cabinet Secretary advised that the UK Government’s ban on conversion practices may have some implications for Scotland in areas of reserved competence.

However, the letter states “It is clear that we will need to take Scotland-specific action both in terms of legislative and non-legislative work which would be interdependent although not reliant on the UK Government plans”.

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that work to establish an Expert Advisory Group on banning conversion practices was underway to begin in Spring 2022.

The remit of the group will include:

Recommending an agreed definition of conversion practices.

Drawing together existing data and evidence on conversion practices including international practice

Advising on potential actions to ban, end, or reduce conversion practices

Advising on support for victims and survivors

Advising on aligning any ban with commitments to protect freedom of expression or freedom of relation in line with existing legislation

Advising on how mental health services, religious bodies and other professionals should be supported to provide appropriate services to people seeking help and advice in relation to their sexual orientation or gender identity

The work will also include consideration of international examples.i

The Committee was keen to explore whether Scotland should seek to work with the UK Government or introduce its own legislation and if so, whether barriers would exist in respect of its powers under devolution.

Tristan Gray told the Committee that what they are calling for is covered by devolved powers. He said that the only thing that is reserved is the professional certification of medical professionals.ii

Vic Valentine said “I do not think that there is any specific reason to wait for the UK Government’s proposals in order to try and work jointly with legislation that comes out at Westminster. It is fully within this Parliament’s powers to enact a criminal ban so, given that the committee is putting so much effort into hearing views and engaging with people it would make perfect sense - and be a positive thing - for this Parliament to shape the direction of what the legislation would look like in Scotland, rather than waiting on Westminster, when we do not know exactly when that legislation will be delivered or what it will look like".iii

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s commitment to banning conversion practices and the proposed work of the Expert Advisory Group. However, it has noted witnesses’ frustrations at the pace of progress and that more is not being done now to protect those at risk. The Committee notes that the Scottish Government plans to bring forward legislation before the end of 2023 if it considers that either UK or other legislation does not go far enough.

The Committee agrees that Scotland should not wait for UK legislation to be brought forward and considers that, within the powers available to the Scottish Government and Parliament, Scotland-specific legislation be brought forward as soon as possible. It recognises that work will be necessary to ensure the development of cross-border frameworks and calls on the UK Government to work with the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament on a ban.

Further supportive measures

The Committee heard evidence that a legislative ban itself will not be enough to end conversion therapy and that a range of supportive measures is also needed.

Paul Daly of LGBT Youth Scotland told us that non-legislative supportive work could include awareness raising in schools and further education institutions as these “might be the only safe spaces for young people who are experiencing conversion therapy".i

Vic Valentine agreed that non-legislative measures were equally important and that support for historical victims who are still experiencing mental health difficulties was crucial. He spoke about the importance for those experiencing conversion therapy of having a means to report the practice and “seek a route to escape”. The issue of advocacy is also important. He told us “for lots of survivors of traumatic experiences the criminal justice system can be retraumatising. The system can be quite adversarial and having to recount your trauma in a setting that is targeted at finding out whether you are telling the truth can be retraumatising. It is important that we have people who are able to help survivors to navigate the criminal justice system".ii

A number of witnesses emphasised that the wraparound support should not wait until the introduction of legislation. Paul Daly explained that the topic being discussed resulted in more people reaching out for help. “It needs to be brought in now” he said. “It should have been put in place a long time ago".iii

Jen Ang spoke of a range of additional options drawn from the international human rights framework best practice which included the need for leadership to affirm that LGBT+ people are not “broken or disordered” and also target the false, misleading and pseudoscientific claims that drive conversion practices. She believes there needs to be significant investment to support survivors, including work with asylum seekers who have suffered persecution on the basis of their gender identity or sexual orientation. She told us there is a need for investigative powers to be put in place as there is no merit in banning a practice without a mechanism for enforcement and accountability.

Three areas where support could be prioritised were highlighted by Jayne Ozanne. Firstly, support for survivors in the form of a survivor helpline. This, she told us, would require not only funding but also specialist therapists who understand abuse particularly in a religious setting. Secondly, she would like to see whistleblowing mechanisms and research to identify repeat offenders. Finally, from an education point of view she would like to see a debunk of the fake news surrounding conversion therapy.

Dr Crowther told the Committee “Anecdotally, seeing the Committee take the issue seriously has already made a difference to people who feel that they will be heard and that they might want to share their story. The fact that the Committee has taken the issue so seriously has already made the world of difference".iv

Suggestions for additional measures included:

Immediate statutory provision of publicly funded specialist support services for current survivors, including: a helpline for current survivors and those at risk; specialist advocates to support survivors, provide advocacy in engaging with relevant generalist services, and provide appropriate support for those who are involved as survivors in ongoing criminal prosecutions; and safe and appropriate mental health support.

Statutory provision of publicly funded specialist support services for survivors of historical cases, including a helpline to provide signposting to mental health support services, and funding to enable reporting on the long-term impact of conversion practices.

A programme of work to reach current survivors of conversion practices and those most at risk of the practices, to give them the language to understand their experiences, awareness that it is illegal and that support systems are available, and insight into the harm that has been done to them.

A centralised needs assessment underpinned by research to understand the prevalence, forms, and locations in which conversion practices occurs, both currently and historically, to inform the future commissioning of services for current and historical survivors. This review could also include identification of which institutions and regulatory bodies are most likely to come into contact with survivors of conversion practices.

A comprehensive programme of professionally accredited specialist trainings that should cover safeguarding and awareness issues and competence in providing safe and effective support for all medical and mental health providers, social workers, counsellors, psychotherapists and psychological therapists and related professions, as well as all religious organisations to identify those at risk of or currently undergoing conversion practices.

Development of regulatory standards through professional practice guidelines for medical, psychological, social care, counselling, and psychotherapy practitioners. Regulatory standards must also be developed to cover pastoral care and spiritual guidance provision whose aim is to improve mental and spiritual health.v

The Committee heard strongly expressed views that legislation alone will not be sufficient to address conversion practices and that non-legislative measures will also be necessary to protect and support victims. The Committee heard a broad range of suggestions for support measures which could complement legislation.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government makes resources available to address gaps in support services for survivors and victims of conversion practices. The Committee acknowledges that many of the suggestions would take significant resource and planning but urges the Scottish Government to review these in detail.

The Committee heard strong views that prioritising a helpline, a whistle-blowing mechanism and a campaign to raise awareness including information in schools and more widely, would go a long way in ensuring victims know what conversion practices are, how to identify them and enable individuals to seek help. Consideration should also be given to providing a separate and distinct reporting mechanism for children.

International examples

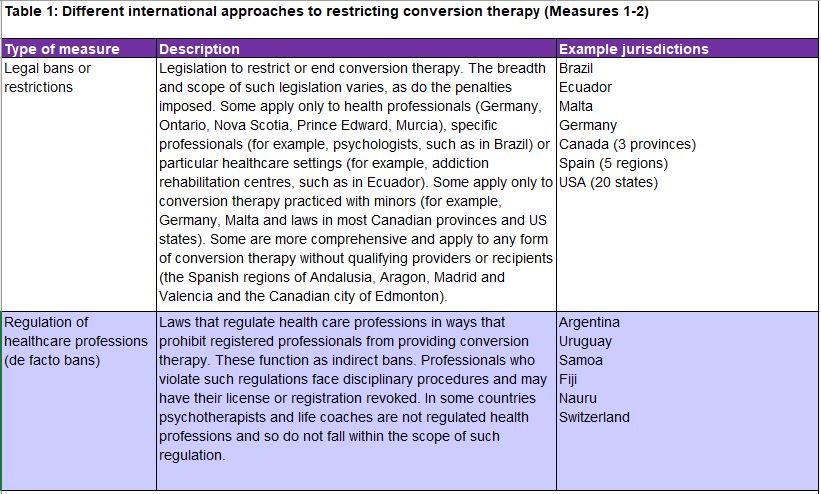

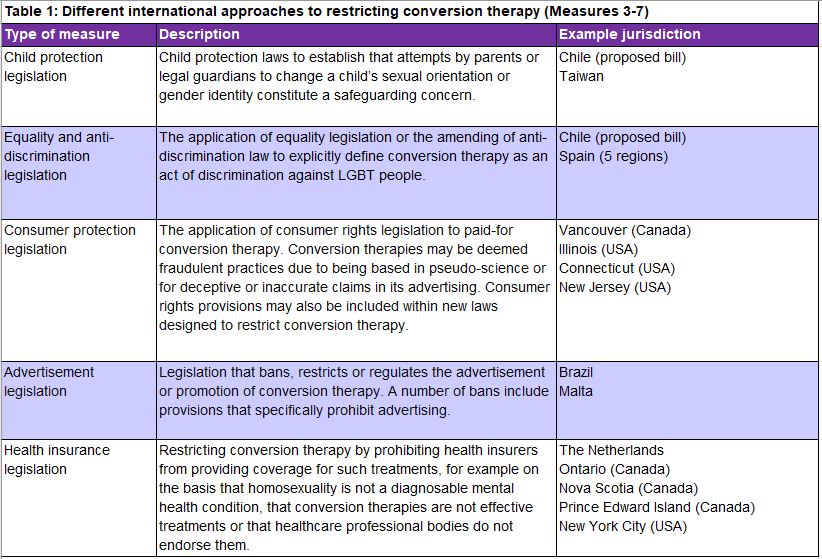

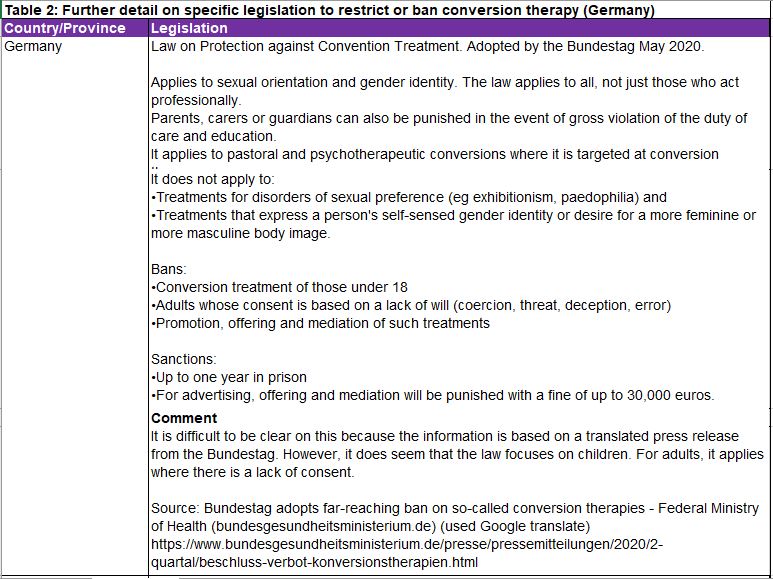

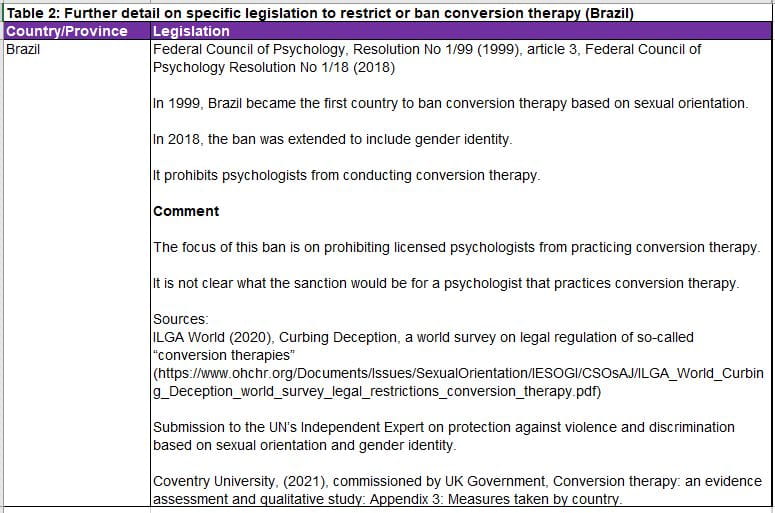

The Committee was interested to understand what interventions other countries around the world were using to ban or end conversion therapy. It discovered that there is a broad range and scope to international legislation and the penalties imposed on perpetrators.

Some countries have chosen to target individual sectors such as healthcare contexts, religious contexts and advertising. In some countries, legislation is already in place or being considered while others question the need for a legal ban where existing laws may be used instead. Approaches such as education and raising awareness are also being considered.

Most countries’ interventions apply to both sexual orientation and gender identity. However, some are limited to sexual orientation only.

The joint written response from the LGBT group stated:

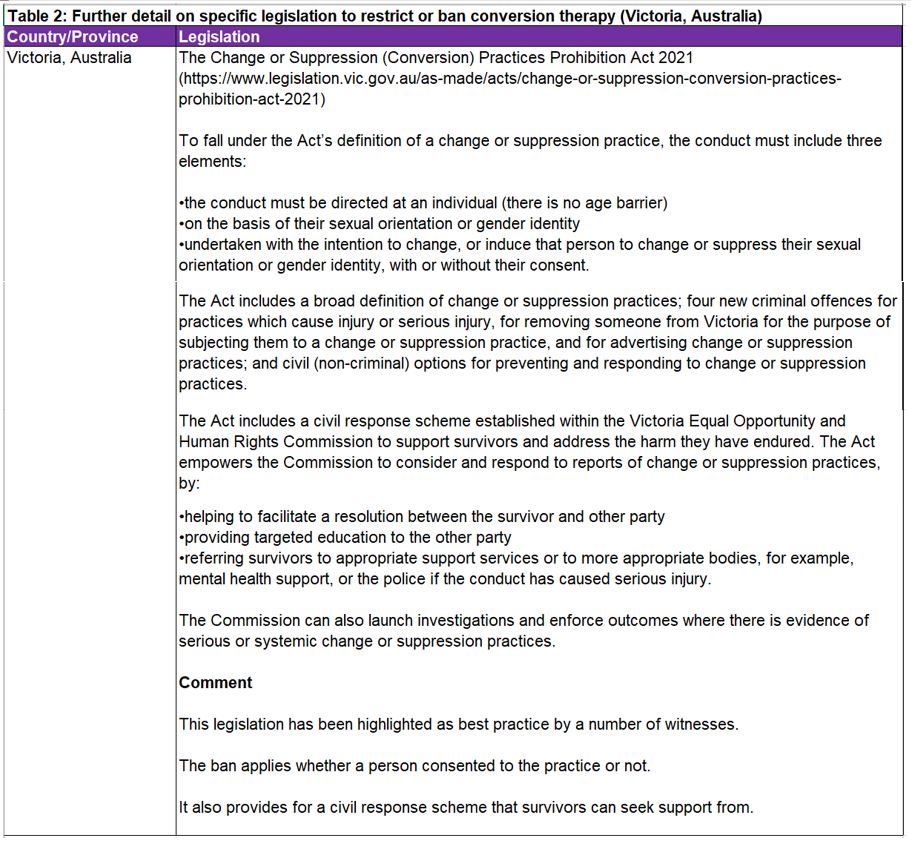

Several countries have introduced national bans on conversion therapy including Germany, while others such as Canada, France and New Zealand are considering bans. At a regional level, states and provinces in the United States, Spain and Australia have also implemented conversion therapy bans, The Australian State of Victoria’s Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Act 2021 has been recognised as a world leading piece of legislation.i

Blair Anderson agreed that Victoria has what they considered to be best practice and includes the criminal ban that they are calling for. “This Parliament would have to strike its own distinct path in the non-criminal legislative aspects” he told us. Other countries like Germany, he said, had similarly strong legislation.

This was echoed by other witnesses including Jayne Ozanne “Of the three pieces of legislation in Australia, the Victoria is seen as the gold standard.” However, she considered there are improvements which could be made such as a mechanism for compensation for victims. The definition also includes “change” and “suppression” but does not include “cure”. She told us “I would urge you to ensure that you include “cure” in your definition because that term reflects the mindset of those who carry out these practices".ii

The Committee heard that it is too soon to see the impact of this new legislation, but it could provide a model to follow.

The Act bans change or suppression practices but provides a range of options for preventing and responding to these practices. It includes a broad definition of change or suppression practices, four new criminal offences for practices which cause injury or serious injury for removing someone from Victoria for the purposes of subjecting them to a change or suppression practice and for advertising change or suppression practices and civil (non-criminal) options for preventing and responding to change or suppression practices.

In addition, the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission has a role to play. The Act includes a civil response scheme established within the Commission to support survivors and address the harm they have endured. The Act empowers the Commission to consider and respond to reports of change or suppression practices, as well as launch investigations and enforce outcomes where there is evidence of serious or systemic change or suppression practices.

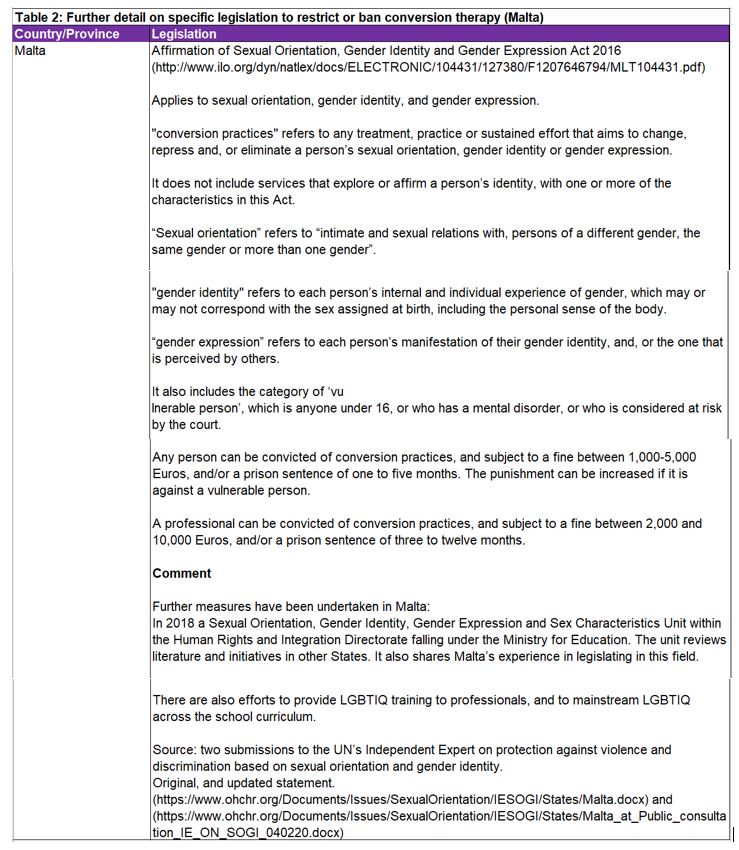

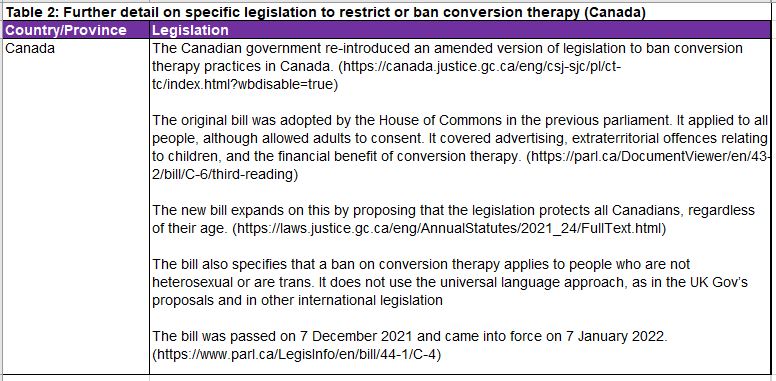

Tables 1iii and 2iv which set out different international approaches to restricting conversion practices and provide further details on specific legislation to restrict or ban conversion practices, can be found at Annexe B to this report.

The Committee found it helpful to hear international approaches to restricting and banning conversion practices and heard evidence that the Victoria legislation in Australia provides one of the best practice examples.

The Committee noted concerns around how enforcement of a ban could be effective and believes that consideration should be given to how this role could be fulfilled by a public body in ensuring investigation, enforcement and accountability is possible. The Committee notes that this enforcement role in Victoria, Australia is carried out by the Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission. The Committee urges the Scottish Government to consider this issue at this stage to ensure the correct mechanism for investigation and enforcement could be put in place.

In conclusion, the Committee is mindful of the volume of evidence that is already available, including the written and oral evidence it has received and considers it is important to bring forward legislation promptly. While noting the respective positions of the UK and Scottish Government and their commitments to bring forward legislation, the Committee is concerned that progress has been slow. It will therefore explore the merits of alternative options which might speed up the process. It would welcome discussions with the Scottish Government on the role of the Expert Advisory Group and the potential options of the Committee and the Scottish Government working together to bring forward a ban as quickly as possible.

Annexe A

The Committee received a significant amount of written evidence from organisations and individuals during the course of its inquiry. Submissions which have been accepted as written evidence by the Committee have been published online.

Agendas, minutes and the Official Reports from the relevant Committee meetings where oral evidence was taken can also be found online for:

Annexe B