Pre-budget scrutiny report

Background to budget scrutiny

The Committee agreed that the central focus of this year’s budget scrutiny will be on promoting employment and encouraging fair work, covering the roles of Scottish Enterprise (SE) and Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) and newly devolved employability programmes.

The Committee sought written views over the summer and received 22 responses. The Committee took oral evidence from Skills Development Scotland (SDS), Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO), Scottish Council for Development and Industry (SCDI), Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) and Employment Related Services Association (ERSA). We also heard from Scottish Enterprise and Highlands and Islands Enterprise following publication of their annual reports and the Cabinet Secretary for Finance, Economy and Fair Work (the Cabinet Secretary), along with the Minister for Business, Fair Work and Skills (the Minister).

That Committee would like to thank all those who engaged with its pre-budget scrutiny work. The Committee is also grateful to those who submitted written evidence in relation to community and locally owned energy. That evidence is summarised in annexe A. The Committee did not have sufficient time to take oral evidence on this issue but asks the Scottish Government to respond to the points raised. We will continue scrutinising this issue in our ongoing budget and energy scrutiny work.

Devolved employment support and the Scottish Government budget

Background

New powers to provide employment support services for specific groups (people with disabilities and those further removed from the labour market) were devolved to the Scottish Parliament under the Scotland Act 2016. These employment support services replace schemes previously provided by the UK Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

In September 2016, the Scottish Government announced the launch of two transitional programmes to be introduced for one year from April 2017: Work First Scotland (replacing Work Choice) and Work Able Scotland (replacing the Work Programme for claimants with a health condition or disability).

These transitional programmes were then replaced by a new programme, Fair Start Scotland, in April 2018. The current round of contracts covers three years – 2018/19 to 2020/21.

Previous spend and performance - transitional programmes 2017-18

Level 4 budget figures published last year show the Scottish Government committing around £17m in 2017-18 for the transitional programmes.i

Statistics were published in August 2018. These show a total of 5,527 people joining the two programmes between April 2017 and 30 March 2018, from 8,997 referrals. This represents a join-up rate of 61%.ii

According to the Scottish Government-commissioned evaluation, ‘lessons learned from Work Able Scotland and Work First Scotland have helped in the design and delivery of Fair Start Scotland, and will continue to do so in future iterations of employability services in Scotland.’iii

Work First Scotland was set-up to provide employment support for up to 3,300 customers with a disability, who wanted and needed help to enter and remain in the labour market. This was a voluntary service.

Work First Scotland offered 12 months of support to disabled customers split between six months of pre-employment support and six months of in-work support. The vast majority of referrals (73%) made to Work First Scotland were by Jobcentre Plus advisers.

The Scottish Government announced the launch of Work Able Scotland in March 2016. It was set-up to support up to 1,500 starts for eligible customers with a health condition. Two-thirds of Work Able Scotland customers had mental health conditions.

Skills Development Scotland (SDS) managed the contract on behalf of the Scottish Government. However, the service was delivered by three contracted service providers: Progress Scotland, The Wise Group and Remploy.

An entirely voluntary service, Work Able Scotland supported people using coaching from a dedicated case manager and coordinated access to skills and health support.

SDS were responsible for managing the Work Able contract and are also on the Government’s Employability Advisory Group.iv In its submission, SDS provides the following summary of recent evaluation:

indications are that the transitional services, Work First Scotland and Work Able Scotland have had some success in ensuring good levels of participation for voluntary programmes and positive attitudes towards the service offer. The phase one evaluation report found that 63% of WFS and 41% of WAS participants now feel more confident they could take a job while 59% of WFS and 48% of WAS participants now feel better at identifying job vacancies which are suitable for them. As for programme participation, nearly half of all customers joined because they felt the programme could help them back into work while more than a third were attracted by the idea of receiving additional help and support.v

Fair Start Scotland

Fair Start Scotland (FSS) provides support for disabled people and people claiming reserved benefits who are at risk of long-term unemployment. Participants are helped to overcome barriers to employment through the provision of up to 12 months pre-work support and up to 12 months in-work support. Services may include help with job seeking and applying for jobs, mentoring, coaching and training.

It is delivered in nine areas across Scotland ‘to reflect the reality of Scotland's geography, regional economies and population spread.’i

According to the Scottish Government, Fair Start Scotland is based on the following principles:

Delivery of a flexible 'whole person' approach;

Services that are responsive to those with high needs;

A drive towards real jobs;

Services designed and delivered in partnership;

Services designed nationally but adapted and delivered locally; and

Contracts that combine payment by job outcome and progression towards work.i

FSS is aimed at supporting those people who are furthest from the labour market (but who want to work). The Scottish Government aims to support a minimum of 38,000 FSS referrals over 3 years, from 2018/19 to 2020/21.

Anticipated budget for Fair Start Scotland in 2019-20

Level 4 figures published at the time of last year’s Draft Budget committed £30.4 million to the newly devolved employment support services in 2018-19.i It is anticipated that the budget for 2019-20 will be around £32 million; however there is a recognition that eventual spend will be demand-driven and dependent on the state of the economy/labour market.

The Scottish Government has allocated a budget of up to £96 million for FSS in relation to referrals over the initial 3-year period (i.e. March 2018 to April 2021).

According to the Scottish Government, the final Fiscal Framework settlement from the UK Government delivered £37 million for employment support for the period 2017 to 2020. This is significantly lower than was anticipated at the time of the Smith Commission agreement. As set out in the 2016-17 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government has committed to providing an extra £20 million per year to the newly devolved employability services.

The Minister highlighted that the DWP spent around £54 million per year on the work programme and work choice in Scotland prior to devolution of the service, whereas the Scottish Government was given £10 million per year, and felt the need to leverage in an additional £20 million.ii

When asked about funding levels, Gordon McGuiness of SDS explained that the funding is part of a wider package of support including the Employability Fund. This point was echoed by SCDI. SDS also highlighted the impact of falling unemployment on the demand for the service.iii

Kirsty McHugh of ERSA highlighted the fact that the reduction in funding was applied to the DWP’s own programme too. She explained that the majority of jobseekers will continue to be supported by Jobcentre Plus; Fair Start Scotland is a targeted programme that will support only 38,000 over the three years.iv

As a payment by results programme, Kirsty McHugh warned that the full allocation of £96 million might not be spent and made a plea for any underspend to be allocated to other jobseekers.v

However, Helen Martin of the STUC suggested that more budget is needed ‘because the employability services are now looking to place people who are quite difficult to place and who historically have faced quite a lot of barriers to getting into employment’. She went on to say:

That sort of support requires more budget rather than less, and it potentially creates challenges for the providers... They are potentially having to deal with more complex things and need to be innovative, and it is difficult for them to do that when their budget is falling.vi

Overall budget for employability services and alignment with other services

CAS and others explained that barriers to employment and the causes of long-term unemployment can be complex and varied, and the solutions will involve a range of policy areas including health, mental health, education, employment and social security.i Other interventions have to be considered alongside employability services. Social Firms Scotland underlined this point by saying that ‘for people furthest from the labour market, employability is not the issue, inclusion is.’i

John Downie of SCVO explained that some people need support before they begin Fair Start Scotland in order to address other issues such as alcohol or drug problems.iii He argued that there is a lack of coherence around the overall employability budget, which includes FSS but covers other programmes and services, and how it is spent:

The £660 million is spent by a variety of agencies—public, private and third sector—and we are not aligning it effectively in a way that takes a look at the persons and what their needs are. At the moment, you can access a pot of money to get support but that cuts you out from another level of support that you might need.iv

The Minister agreed that the system could be more coherent. He referred to the report , ‘No One Left Behind: Next Steps for the Integration and Alignment of Employability Support in Scotland’,v which sets out the Scottish Government’s next steps to ensure greater alignment and integration of the various employment programmes. He also agreed that employability programmes must align with other statutory services such as housing and health.vi The Minister referred to £2.5 million of funds allocated for integration and alignment, which is funding 13 projects across 18 local authority areas and is designed to test how to better integrate services.vii He said:

The £660 million figure came from analysis by Cambridge Policy Consultants, which we put in place, if I recall correctly, to analyse and understand the level of expenditure. The lion’s share—the vast majority—was through local authorities.viii

Presently, the Scottish Government does not know what services each local authority is providing. The Minister set out the Scottish Government’s plans to map out provision of services across Scotland ‘as soon as possible’.ix

The Committee believes that it is vital to know the extent of provision and expenditure across all employability programmes. The Committee notes that the Scottish Government is currently mapping out the provision of services across Scotland. This should be a clearly coordinated information gathering exercise, carried out with the cooperation of local authorities, with a view to developing a coherent, strategic and cross-cutting plan. We urge the Scottish Government to provide the Committee with this further information on employability service provision as soon as possible. The Committee will examine that data as part of its ongoing budget scrutiny.

The Committee welcomes the indication from the Minister that work is being done on aligning employability and other complementary services. This is an opportunity for the Scottish Government to galvanise those services into a more coherent approach. The Committee requests an update on this work once these projects are completed.

Employability fund

The Employability Fund is funded and administered by SDS and supports the Youth Employment Strategy. It supports services which have been developed to address the specific needs of local areas. SDS said:

We do this by working with local employability partners, to maximise the resources that are available in their area and avoid duplicating existing employability services. By working closely with our partners, we make sure that the fund is aligned to local areas and maximises opportunities for individuals. Local training providers work with employers to understand their skills needs and help them find and train the right individuals.i

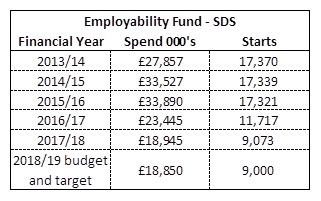

SDS provided the Committee with figures on the Employability Fund:ii

The budget for the employability fund has gone from almost £34 million in 2015-16 to £19 million in 2017-18, which is a drop of £15 million or a 44 per cent cut.

The Minister explained that:

The employability fund was put in place at a time when the labour market was very different from how it is now. When the employability fund was first instigated, youth unemployment levels were running significantly in excess of where they are today. Thankfully, we have travelled further and investment in specific programmes largely reflects where we are now.iii

Length of contract

FSS contracts are for three years whereas Employability Fund contracts are for one year. Gordon McGuinness confirmed that SDS go through the procurement process on an annual basis.i Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said that generally, one-year contracts are ‘hard to deal with’ for the third sector and other organisations.ii

The Minister explained that:

the reason why Fair Start Scotland contracts apply for a longer period of time is because many of the people who participate in that programme will require a much longer period of support—longer than a year. The employability fund is designed in a very different way: it is designed to support people over a shorter, sharper period, rather than many years. By its nature, it is a different type of system.iii

He went on to say that there has been stability for the openly procured element of the Employability Fund over each of the past three years in terms of both funding and the number of places.iv

The Committee notes the evidence that one-year contracts can be problematic. Tendering for work takes time, effort and money, and doing this on an annual basis imposes unnecessary insecurity on providers. The Committee recommends that organisations are given three-year contracts under the Employability Fund.

Voluntary programme

Unlike the UK Government programmes it replaces, Fair Start Scotland is a voluntary service with no sanctions over those referred to the programme for failing to meet the requirements. The Minister said:

We decided to make the programme voluntary, because Parliament has heard significant concerns about the efficacy—or lack of it—of sanctioning in supporting people into employment. We have seen a variety of academic and third-sector campaigning organisation assessments that show that people who are sanctioned might get into employment, but it will only be for a short period before they end up back in the benefits system. That speaks to me of the necessity of operating a system that does not compel people to take part.i

This has been welcomed by many stakeholders. For example, CAS stated:

CAS warmly welcomed the Scottish Government’s decision that no referrals for benefit sanctions would be made in the new employment services, and that participation would not be mandatory, in contrast with the previous system. CAB clients engaging with the previous Work Programme commonly sought advice because they had been sanctioned, in some cases in harsh circumstances, such as being less than five minutes late for an appointment with the Work Programme provider.ii

Whilst also welcoming the voluntary nature of FSS, North Ayrshire Council also urged some caution:

People need to see a clear route to employment and need to be convinced that this is a viable outcome. Many of the customers will have taken part in employability programmes before and therefore may be cynical about their effectiveness – training for the sake of training must be avoided, linkages to real jobs must be visible. The programmes need to focus as much on motivation and positive thinking as they do on technical skills and qualifications.ii

Similarly, SCDI also supported the voluntary nature of FSS but asserted that that there needs to be more investigation of the fact that only 60 per cent of the people who volunteered actually started the transitional programme.iv

Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said that some people do not realise that FSS is voluntary when they are referred and then drop out early in the programme. This counts as a referral and these people are then excluded from future participation in the programme.v Aberdeenshire Council confirmed that they have experience of this scenario.ii

SLAED argued that although engagement is voluntary, individuals may still feel pressure to agree to a referral by their DWP Work Coach, which could lead to resources being wasted on following up with people who have no real interest in participating.ii

The Committee welcomes the voluntary nature of FSS, but notes that people are excluded if they start the programme and drop out early. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should review this policy with a view to giving people further opportunities to engage with the programme.

Fair Start Scotland contracts

FSS service providers are either private companies, third sector organisations or local authorities.

Following a similar model to that used by previous UK governments, FSS services are contracted out by the Scottish Government using a process of competitive tendering. The Government pays successful delivery agents to provide FSS services, part of the fee being performance-related (payment by result).

Unlike the UK-wide Work Programme, the Scottish Government is relatively prescriptive about the services they are paying for. Key Delivery Indicators covering pre- and in-work support periods apply to all providers. These describe what is expected in areas such as assessment of need and action planning, frequency of engagement, and support to stay in work.

The DWP, on the other hand, had previously adopted more of a ‘black box’ approach for its Work Programme, whereby it was up to individual contractors to decide how best to get people into sustained work.

The Scottish Government launched its Fair Start Scotland call for tenders in March 2017; contracts were awarded in October 2017.i

A Tender Evaluation Panel was set up and tenders were selected on the basis of the most economically advantageous bid, having regard to the price and quality of the proposals against defined evaluation criteria. The objective of the evaluation was to select the tenders which represented the best overall value for money against a number of criteria. Various weightings were applied.

When the successful bids were announced, there was considerable criticism from the third sector due to the high number of contracts won by private companies.ii Of the nine geographic areas, only Forth Valley is led by the public sector (Falkirk Council), while two - the North East and West Scotland – are led by the third sector (Momentum Scotland and the Wise Group respectively).

John Downie of SCVO suggested that the principles of FSS are right but the procurement process is actively working against achieving those aims.iii He provided feedback from their members on the awarding of contracts:

the time that was afforded to adopt a single contract within each area minimised the involvement of small and medium sized third sector organisations, particularly the more specialised ones; [that] the procurement process was not sufficient for the formation of consortia; and [that] the commissioning process has been overly complex and entirely inaccessible for many organisations.iv

Social Firms Scotland concurred that there was insufficient time to engage with other organisations to develop meaningful consortia and argued that this has had an impact on the diversity of suppliers, in particular smaller organisations.v ERSA also concurred.vi

North Ayrshire Council argued that the procurement process ‘naturally favours those providers who can invest in professional bid writers or who can set stretching and often unachievable targets on the basis they can afford to accept the financial risk.’vii

SCVO confirmed that a lot of smaller and medium-sized organisations were opting out of bidding for any of the contracts because the procurement process favoured larger organisations, ‘our concern was not that the private sector would win all the contracts but that all the big boys in the third sector would.’ Although some small and medium-sized organisations are sub-contracting some work, there is a concern that they are being squeezed.iv

SLAED concurred, ‘only larger organisations will manage to deliver these contracts, and these don’t always deliver on their commitment to include smaller discreet interventions.' They also believe that the contracting process does not always meet the needs of local areas, particularly smaller areas, which can be unattractive to bidders for reasons of viability.vii

When asked about the mix of sectors delivering the programme, including through subcontracting, John Downie of SCVO said:

In some areas, it is working quite well. In other areas, a number of third sector organisations that were initially on some of the private sector prime contractors’ subcontracting lists are not taking up those opportunities.x

The Committee notes that there are a number of issues relating to the procurement process, including the requirement for time to build consortia and questions over whether it is accessible to small and medium-sized organisations.

The Committee recommends that, as part of a review of the initial programme, the Scottish Government seeks to address these issues by ensuring that there is sufficient time to bid and taking steps to ensure that the process is accessible to all organisations, regardless of size.

Payment by result and outcomes

Background

The FSS funding model consists of:

Implementation costs: set-up cost payments to service providers, introduced to reduce barriers to entry for smaller organisations.

Service fee: based on 30% of the total contract value (excluding implementation costs) from the Service Providers bid.

Job outcome fees: job outcome payments where a participant has entered a job and sustained for 13 weeks, 26 weeks and 52 weeks.

The level of fee paid varies depending on the client group of participants.

Parking and creaming

In their written submissions, organisations such as the STUC, North Ayrshire Council, SCVO and Social Firms Scotland, voiced some criticism of the payment-by-results approach. Specifically, they argue that it skews behaviour towards ‘parking and creaming’, i.e. helping jobseekers who are more ‘job ready’ and ignoring everyone else.i

North Ayrshire Council believe:

The issue of ‘parking and creaming’ is an almost inevitable consequence of payment by outcome models. As these models tend to significantly undervalue the true cost of supporting those most disadvantaged into jobs, then parking and creaming become an economic imperative for providers. The only way to avoid this is to avoid payment by outcomes completely and pay the actual costs of supporting each customer. Or there is a middle ground where some financial incentives can be built into the model to reward providers for intermediate outcomes – however such systems are mired in complexity and open to abuse.i

ERSA has a different view:

In relation to ‘parking and creaming’, it is worth the Committee noting that the new iteration of Scottish programmes are not designed for those who are close to the labour market and thus it is unlikely that there were will be jobseekers ‘to cream. i

In response to comments made about ‘parking and creaming’, the Minister said:

One of the ways that we responded to that concern was to ensure that there is an up-front fee. When a person engages with the programme, the provider gets 30 per cent of the overall value of the fee that they are entitled to for someone who participates.iv

Payment by result – impact on service and providers

North Ayrshire Council argued that payment by outcomes ‘generally vastly underestimate the true cost of achieving outcomes and as such contractors generally deliver services with cost in mind rather than the personalised, individualised services that most agree are required’.i

SLAED argue that whilst the new FSS service is intended to be person-centred, the level of performance and key delivery indicators required to be met by providers makes delivery very process driven. They believe that although clear guidelines need to be in place, there also needs to be a degree of flexibility to allow tailored services to individuals at a local level.i

Kirsty McHugh of ERSA also highlighted the impact of the payment-by-result model:

third sector organisations can be nervous about payment-by-results contracts and sometimes they do not have the ability to do the financial modelling. That applies to not just third sector organisations but to smaller organisations more generally, so a small private sector organisation might have the same issue.iii

Inclusion Scotland concurred that the payment by referral model can work against certain providers offering services:

There is some evidence that previous third sector suppliers of employment support services for specific groups, for example disabled people or single parents, are being frozen out by the new service providers. For example, instead of being funded to provide a service to which clients can be referred, they are now only being offered payment by referral, which leaves them unable to maintain the staff and infrastructure necessary to provide the service. This will impact on the breadth and depth of employment services available for those who need specialist support.iv

Asked about whether any subcontractors have stopped putting themselves forward for those contracts, Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said:

The Scottish Association for Mental Health decided not to be part of this. It goes back to the very first question about the money available for something called individual placement support. That is a very well-evidenced mental health intervention, which integrates mental health support and employability support. It is expensive. SAMH is an expert in relation to that. It is probably not affordable on this programme.v

The Government calculates a maximum cost per client of around £9,000 (for those people needing intensive support).vi However, Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said that individual placement support costs considerably more:

The figures I have seen quoted for proper individual placement support at the fidelity levels are about £20,000 a place.v

The Minister argued that the model is person centred and, within that model, the Scottish Government has provided funding to explicitly recognise that some people might require more support to get into employment, ‘access to such support is within the full funding that we have provided.’viii He also stressed that supported employment is a key part of provision and that the Scottish Government is ‘operating individual placement support in order to support people with poor mental health or who face mental health challenges.'ix

The Committee notes evidence that SAMH, who are experts in relation to individual placement support, have opted out of its delivery due to funding constraints. Given that this is cited as being an effective intervention, the Committee recommends that the Scottish Government pilot this service to be delivered by the third sector within the next three years before the new round of FSS contracts. This could be funded by any underspend in the Fair Start Scotland budget.

FSS outcomes

A number of written submissions expressed a view that the measure of success of FSS is too narrow and should be broadened. Social Firms Scotland, for example argue that:

Whilst defining a job as the headline outcome can be practical and pragmatic, there is a significant issue in defining that job (to meet a contract outcome) as 16+ hours. For some people with complex needs who want to work and contribute to society, this is challenging or impossible

[we] believe outcomes need to adapt to recognise that progression, for some people, is also a significant and important outcome. For many individuals it is about being valued for their contribution, increasing their confidence, communication, and improving their health and well-being. Outcomes should, to some degree, take into account what’s important to the individual and they – and the social enterprises that support them – should not be penalised or their outcome minimalised if a job is not a realistic outcome for some people.i

CAS agreed:

You should measure sustained job outcomes, but it is important to capture softer outcomes as well, given that the people who are involved with the programme are quite far from the labour market. Measurements other than getting people into work could be used in determining success.ii

Argyll and Bute Council said:

All positive outcomes should be measured. Participants may move into further education which is currently not recognised. In many cases this is a massive step for some participants and the qualifications obtained provide a positive step towards securing sustainable employment.i

STUC also believes that the focus should shift, with there being ‘way too much emphasis on preparing the person for work rather than preparing the work for the person.’ii On outcomes they suggested:

If the employability service says that it is successful and the workers themselves say that it is successful for them, that can be the measure of success rather than hitting statistical targets that have been set at the centre and applied rigidly in every case.v

Inclusion Scotland stressed the need to review outcomes across the protected characteristics:

Proper equality measurements which look at pay, occupation, longevity, hours of employment across protected characteristics should be gathered, taking account of EHRC guidance, in order to track whether there are any significant variances in outcomes across protected characteristics, and particularly where a person has more than one protected characteristic.i

SLAED argued that recognition should also be given to job density within an area and this should be taken into account when setting job outcome targets.i

There was also a plea for people to be able to start a job at a certain level and number of hours with the possibility of increasing their hours and responsibilities over time.viii The ability for people to progress once in a job was also highlighted by SCDI and CAB.viii SCDI also said that a measure of progression could be health and wellbeing, particularly for those who may have had alcohol issues.viii

Alternative payment model

Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said, ‘for people who have very intense needs, it is wrong to have too much focus on the result, and more of the money has to come up front.’i John Downie of SCVO said that a mixed model was needed (both payment by result and payment up front). He suggested a payment model in which a percentage of the payment is based on outcome but also measures people’s progression.ii

It was suggested by SCVO that the payment models and outcomes will need to be reviewed:

Over the next 18 months, our thinking needs to get a bit more sophisticated to ensure that the next stage of Fair Start Scotland builds on where we are now. The Government seems to be up for that debate, but we need to engage the private sector, the public sector and the third sector in that.iii

The Minister said that ‘the approach is right for fair start Scotland. If we are leveraging in £96 million of investment for an employment programme, I want to see as many as possible of the people engaged in that programme—ideally everyone, but I recognise the reality that it will not be everyone— ending up in employment and sustaining that employment. That would be a good outcome.’iv

The Minister said that there is a role for other parts of the system to have different outcomes, which might be people not necessarily ending up in employment but being closer to employment by, for example, transitioning to something such as Fair Start Scotland.v

It is clear to the Committee that the payment by result model must be monitored carefully. As it currently stands, it does not sufficiently recognise the complex nature of the people engaging with the services. The Committee invites the Scottish Government to build flexibility into the outcomes, to allow them to be tailored towards the person’s needs. The Committee agrees with evidence which suggested that progression towards employment should be considered a successful outcome as well as sustained job outcomes.

Referrals

As was the case with previous programmes, the majority of referrals to FSS will come from Jobcentre Plus advisers. Each customer referred and accepted on to FSS are assigned to one of three service groups – core, advanced or intensive. Each have differing levels of associated service provision and outcome payment values.

The Committee was told that the number of referrals FSS receives will be critical. Kirsty McHugh of ERSA said that work coaches and others in Jobcentre Plus may take a while to understand the criteria of a new programme such as Fair Start Scotland.i

Argyll and Bute Council described interactions with Jobcentre Plus (JCP):

the Council’s Employability Team staff has built up good relationships with JCP staff across Argyll and Bute through employability contract delivery over a number of years.ii

Solace highlighted a lack of control over the suitability of referrals to the new FSS service and believes that there should be a mechanism for pre-referral discussion between Jobcentre Plus and providers.iii

The Minister confirmed that because Jobcentre Plus is in most direct contact with those who stand to benefit from the FSS programme, it will remain the main conduit for referral. However, he explained that the Scottish Government is actively trying to explore other referral mechanisms.iv

The Committee notes the key role of Jobcentre Plus in referring people to the Fair Start Scotland programme. The Committee will seek to engage with them as part of its ongoing budget scrutiny over the coming year.

The Committee welcomes the development of other appropriate referral mechanisms to the programme and will monitor the progress of this work.

Apprenticeship levy

A UK-wide apprenticeship levy came into force in April 2017, requiring larger companies and public sector bodies that have pay expenditure of over £3 million per year to pay 0.5 per cent of their annual bill to the government for apprenticeship training.

Homes for Scotland explained the impact of the levy:

Given that the Apprenticeship levy largely replaced money previously received to Scotland via the Barnett formula, we are led to believe that whilst the levy resulted in a higher allocation of monies to Scotland, this was off-set by Scottish public sector levy contribution which in the end resulted in a reduction in public spending power in Scotland by approximately £30m. This meant that some of the levy money was used to fund ‘business as usual’ resulting in perception amongst home builders that they were paying more money for the same service.i

Atos UK and Ireland spoke of the process for accessing the funds:

We have not successfully been able to access levy funding in Scotland due to the way the fund is administered in Scotland; the Scottish Government uses its proportionate share of the levy funding to support existing programmes, unlike in England, where employers can receive funding to spend on apprenticeships.i

Greene King (which employs over 3,000 people in Scotland, at their brewery in Dunbar and in pubs across the country) described a similar scenario. Although they contribute £200k to the Scottish apprenticeship system through the Apprenticeship Levy, there is currently no guarantee that they will be able to access those funds from SDS for use in delivering their apprenticeship programme; last year only 18 of their 76 new starters in Scotland were funded by SDS.i

Gordon McGuinness of SDS spoke of the impact of the apprenticeship levy on the public sector, ‘a figure that sticks in my mind is that NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde has contributed about £6 million to the levy, which is a significant amount.'iv He told the Committee:

A number of companies have been frustrated in trying to access to the levy. We have created a service that tries to maximise what individual companies can get from the levy in Scotland across the skills system.iv

Another example of public sector investment in the levy was given by Argyll and Bute Council:

The Argyll and Bute Council pays in excess of £650k per annum into the levy. This is in no way recouped by the limited scope the council has to access small (£10-15k) amounts of money from the Levy for workforce development. This therefore restricts the public sector from investing in workforce development, as overall our budgets are reduced significantly.i

The Minister told the Committee:

The UK Government is responsible for Funds raised via the Apprenticeship Levy. An adjustment is made to the Scottish block grant based on forecasts by the UK Government of funds generated by the Levy. However this adjustment largely replaces previous Skills funding received. Given the public sector are in scope for the Levy alongside the private and third sectors, the net effect is a reduction in public sector spending power in Scotland.vii

The Scottish Government recently received data on the apprenticeship levy from HMRC and are currently analysing it.vii

North Ayrshire Council argued that the levy money is being used inappropriately in Scotland for the following reasons:

Additionality is unclear.

Employers not clearly and consistently getting anything back from paying the levy.

Levy monies not clearly being used to incentivise employers to do things differently.i

SCVO described the levy as a tax for the Scottish third sector with many organisations forced to write-off this cost (amounting to c.£2.3million):

In effect, the levy in Scotland has led to charities paying into a pot from which only the public and private sectors benefit (whilst the private sector gain Modern Apprenticeships, the public sector gains additional funding through the Barnett formula). There is no parity of esteem in terms of the treatment of the public and third sectors. This must surely be an unintended consequence.i

The Committee notes the issues raised in relation to the apprenticeship levy. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to share its analysis of the HMRC data as soon as possible. The Committee will examine this issue in more detail as part of its forthcoming inquiry on skills.

Scottish Enterprise and Highlands and Islands Enterprise

The Committee usually undertakes annual scrutiny of the Scottish Government’s spend on enterprise agencies, Scottish Enterprise and Highland and Islands Enterprise. As agreed during last year’s budget scrutiny process, both agencies published their annual reports and business plans in time for this year’s pre-budget scrutiny.

Expenditure

Table 1 shows that Scottish Government grant-in-aid to Scottish Enterprise reduced considerably between 2008/09 and 2017/18, by 27% in real terms (using the SPICe deflator).i [

Table 1: Scottish Enterprise expenditure and funding (2008-2018) (£ Million) 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 Total Cash Expenditure 312.4 337.9 309.1 304.6 288.0 295.8 316.7 298.4 310.3 301.4 Funded by: Including Grant in Aid from SG 257.7 281.5 217.2 245.3 235.4 248.9 207.9 217.0 197.8 218.0 Plus other income 45.6 42.6 82.1 51.9 51.9 46.4 104.7 93.4 116.4 96.5 Total income 312.4 337.9 309.1 305.5 290.0 296.8 317.6 310.4 314.2 314.5 Net underspend - - - 0.9 2.0 1.0 0.9 12.0* 3.9 13.1

Table 2 shows that Scottish Government grant-in-aid to Highlands and Islands Enterprise reduced by 9% in real terms between 2008/09 and 2017/18 (using the SPICe deflator).i This is a significantly smaller reduction than that experienced by Scottish Enterprise.

Table 2: Highlands and Islands Enterprise expenditure and funding (2008-2018) (£ million) 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 Total expenditure 83.2 70.9 72.1 65.1 79.5 93.1 96.9 111.8 91.9 91.5 Funded by: Including Grant in Aid from SG 66.0 58.7 59.3 51.2 71.3 57.9 59.7 66.2 63.8 69.5 Including EU/Big Lottery 6.6 4.1 2.5 3.7 2.6 2.3 3.3 2.6 1.2 1.1 Including Business receipts 10.6 8.1 10.3 10.3 8.3 30.2 33.9 43.0 28.9 20.9 Total income 83.2 70.9 72.1 65.2 82.2 90.4 96.9 111.8 93.9 91.6

HIE said that ‘the budget has been relatively stable in cash terms, but of course, that translates into a slight reduction in spending power’.iii

Scottish Enterprise: financial transactions

As set out above, the Scottish Government grant-in-aid to Scottish Enterprise reduced by 27% in real terms between 2008/09 and 2017/18. This is a significant cut over the decade. In response, Scottish Enterprise stated:

Things have changed quite significantly over that decade. In the early part of it we saw a decline in our funding, but in the past few years that has levelled out, and we are pleased with the increase that we got from the Government last year.i

With regards Scottish Enterprise’s budget for the current financial year, there is a significantly higher anticipated Scottish Government grant-in-aid allocation (£289.7m) compared to that received in 2017/18 (£218.0m). Much of this difference is explained by increased financial transaction money.ii According to its business plan, Scottish Enterprise’s financial transactions allocation in 2018/19 will be an estimated £88 million. The comparable sum for 2017/18 was £42 million. This is a real terms increase of 107% over the year.

Scottish Enterprise figures for 2017/18 show an underspend of £13 million; this has mainly been in the area of financial transactions.

Iain Scott of Scottish Enterprise said that £10 million of last year’s underspend was for the the Scottish-European Growth Co-investment Programme, a co-investment programme with the European Investment Fund with matching funding through investors with an aim to reach £200 million of investment. Scottish Government investment in the programme was meant to be £50 million over three years. However, he added that the number of expected deals have not come through, with about £1 million having been committed through only one deal. Iain Scott said:

The Government is committed to the £50 million, over more than the three years that were originally envisaged. We hope to utilise those funds in due course.iii

In subsequent correspondence, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed that a total investment of £2 million has been made under the Programme (£0.5 million from Scottish Enterprise, £0.5 million from the European Investment Fund and £1 million from an EIF accredited Fund Manager). This confirms that Scottish Enterprise have in fact only directly committed half a million of the funds to date.iv

Iain Scott explained that Scottish Enterprise have set a target of £20 million for this year but that they are ‘talking to the Government about whether those funds can be used for other activity this year.’v

In relation to this underspend, Steve Dunlop, Chief Executive of Scottish Enterprise said:

I am marshalling all our resources to try to execute against what Iain Scott says is the positive pipeline that is there, but this is quite a shift for us, and I see cranking up the machine to get those wider, deeper strategic partnerships as the way to deliver that.v

Iain Scott of Scottish Enterprise said that the nature of the Scottish Investment Bank’s activity ‘lends itself very much to financial transactions funding, given that it is restricted to loans or equity investments’. He explained that over the past three years that has increased from about £14 million to £45 million and last year to £88 million:

Our activity in that area is more about the £55 million to £60 million for the Scottish Investment Bank activity, so we are now looking at using those financial transactions for other areas within the organisation, but we have been able to utilise the majority of that though our direct investment function within the organisation.i

Steve Dunlop of Scottish Enterprise spoke of developing partnerships:

Financial transactions money lends us a huge opportunity to partner in a different way from how we have in the past. As we look forward to long-standing strategic relationships with universities, local authorities and so on, financial transactions money will become much more useful in the future. We are in the process of spending that but also understanding how we get absolute best value and strategic output from it in future.i

The Cabinet Secretary stressed that the growth scheme is an umbrella for a range of products and that there was more demand for some products (such as grants) than others (such as guarantees). He explained that they have been exploring bespoke solutions to ensure that they can deliver on the commitment to provide the £500 million of extra support that was announced.ix

In subsequent written evidence, the Cabinet Secretary stated that £102.3 million has now been invested under the Scottish Growth Scheme (both private and public) in 80 companies. It is not clear from the correspondence how much of this investment was provided by the Scottish Government and its agencies.iv

To seek to put the underspend figure in context, the Cabinet Secretary told us that:

the enterprise agencies have received a substantial increase in the 2018-19 budget. A lot of that relates to financial transactions that we have been able to use for equity investment, but there has been a substantial increase from £35 million to £68.5 million.xi

The Committee notes that Scottish Enterprise’s core grant has reduced in real terms by 27% over the past 10 years. Financial transaction money has boosted the headline funding figure in recent years, but these funds are limited to equity and loan funding. It is proving challenging to commit these funds.

The Committee is concerned about the lack of progress in committing the money for the Scottish-European Growth Co-investment Programme. With only £0.5 million invested by Scottish Enterprise out of a pot of £10 million, the programme has not been a success to date.

Given the underspend in financial transaction money over the last year, the Committee does not have confidence that Scottish Enterprise will commit the increased funds, consisting of financial transaction money, which largely accounts for its increased budget for the forthcoming year.

The Committee recommends that Scottish Enterprise take urgent action to ensure that this money is spent to benefit the Scottish economy. We ask Scottish Enterprise to provide us with an update in six months on progress in committing these funds.

Level of spend

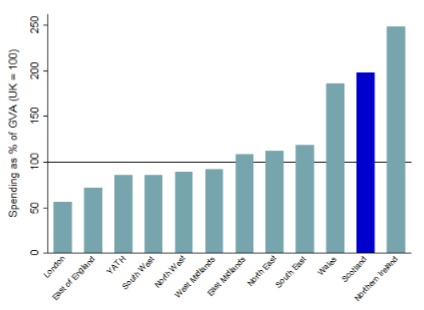

In 2016-17, Scotland spent more than £1 billion on enterprise and economic development; that is a much larger amount per head than most other parts of the UK (as set out in the chart below). During its pre-budget scrutiny, the Committee questioned what has been achieved by these relatively high levels of spending and whether the spend is being directed towards the right priorities.

Source: David Hume Institute, 2018

Source: David Hume Institute, 2018

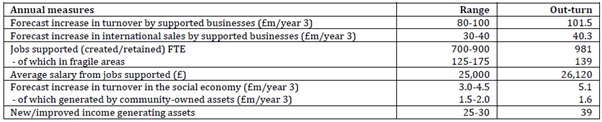

When asked about this, HIE cautioned about comparing ‘apples and pears’ spoke of a ‘holistic economic development approach’ and being able to demonstrate social impacts as well economic return.i In its annual accounts for 2017/18, HIE states that ‘turnover among supported businesses is anticipated to increase by £101.5 million over three years and international sales by £40.3million, following HIE’s support.'ii

Scottish Enterprise states that ‘a recent assessment of our return on investment shows that over a ten-year period every £1 spent generates between £6-9 GVA.'iii

Steve Dunlop of Scottish Enterprise highlighted the recent Barclays dealiv saying that such deals would not have happened without intervention and ‘without people selling what Scotland has to offer’. He described attracting inward investment as a ‘very competitive business’ and said that an enterprise network or something similar is needed to do this.v

STUC agreed:

The STUC firmly believes that the rationale for strong public sector economic development/business growth/enterprise and skills agencies remains extremely compelling.iii

When asked about Scottish Enterprise’s analysis of GVA generated by its spend, the Cabinet Secretary said, ‘there are a range of checks and balances that assure us that how we are investing in the enterprise agencies is achieving the economic outputs that they claim’.vii

The Cabinet Secretary mentioned the 2016 Audit Scotland report, Supporting Scotland’s Economic Growth.viii

The Committee examined that report when it was published. It stated that:

Measuring the impact of economic development activity is difficult but Scottish Enterprise and HIE perform a range of evaluation work to help demonstrate and improve their impact.viii

The Audit Scotland report also highlighted that Scottish Government has not collated the contribution made by individual public bodies, to form an overall assessment of progress against the priorities in its previous economic strategies. The report recommended that the Scottish Government should work with the main partners involved in supporting economic growth to strengthen its approach to developing, delivering and monitoring the economic strategy including:

developing clear targets, timescales and actions for different aspects of the strategy and setting out specific responsibilities for public sector bodies;

estimating total spending on the four strategic priorities, by the main partners involved, to determine whether funding is being targeted appropriately; and

assessing the impact of public sector support for the growth and other key sectors to help determine the most appropriate focus for public sector support.

In its recent report on Scotland’s economic performance, the Committee recommended that ‘any future economic strategy should be accompanied by a strong action and implementation policy, backed up with a monitoring and evaluation plan.’ In its response, the Scottish Government accepted this recommendation saying that it will ‘assist us in our aim of providing a clearer and more transparent approach to the development, delivery and monitoring of our interventions relating to sustainable and inclusive economic growth in Scotland.'x

The Committee notes the Cabinet Secretary’s assurance that Scottish Enterprise’s assessment of the impact of its spend is achieving the outputs that they claim. However, the Committee is keen to understand the detail behind the claim that Scottish Enterprise generates between £6 and £9 GVA for every pound it spends. We recommend that Audit Scotland should carry out a further performance audit report to examine and explain this assessment. This would provide clarity and transparency and would allow the Committee and the wider business community understand how this is being achieved.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s commitment to producing an action and implementation plan for its economic strategy. The Committee supports Audit Scotland’s recommendation that the Scottish Government should set out the role of the enterprise agencies in delivering the strategy as part of the action plan. In future annual reports, the enterprise agencies should report on progress with these actions.

Are the agencies’ targets challenging enough?

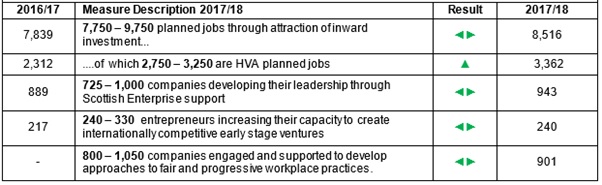

The following table shows performance against HIE’s key targets. HIE met or exceeded all targets for 2017/18:

Similarly, last year’s performance measure targets were all comfortably met or exceeded by Scottish Enterprise, including the following ‘inclusive growth’ performance targets:

When asked about meeting all of their targets for 2017/18, HIE said that it was a challenge to achieve them. They confirmed that their targets are approved by their Board.i Similarly, Scottish Enterprise said that they worked hard to meet their targets and that the targets are increasing year on year.ii

In evidence relating to the enterprise agencies’ targets, the Cabinet Secretary accepted the point that ‘we should ensure that the targets are challenging enough to maximise the opportunities for the Scottish economy’.iii He said:

I would not say that the performance targets have been too easy, but on the other hand I expect us to be able to do more. There are opportunities there and, as the committee requested, we are recalibrating our economic strategy, so we hope that with the range of actions that we implement we will get even more value from our investment.iv

The Cabinet Secretary went on to say:

we know that we want to grow Scotland’s economy and so we will have to push the enterprise agencies to do that. If that means sharpening up some of the performance targets, so be it.iii

HIE explained the role of the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board in relation to its targets:

it will not aggregate the measures that we report on individually, but will use a set of measures that it determines to be the important measures for looking at activities, outcomes and impacts. That will make the difference to the overall prize of improving Scotland’s productivity performance.vi

Similarly, Scottish Enterprise explained that the Strategic Board will bind the organisations together with strategic targets:

the board will have a strategic, shaping, direction-of-travel influence and then the boards in each of the organisations will go into their budget-planning cycle and respond accordingly, which is what we will do.vii

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed that the Strategic Board will provide a ‘more consistent framework’ and ‘bring more consistency to how we challenge and rate the enterprise agencies and compare them to one another.'iv

The Committee notes that the enterprise agencies set and mark their own homework. There is a role for the Strategic Board to ensure that their targets are sufficiently challenging. The Committee welcomes the role of the Strategic Board in performing a ‘challenge’ function; it must ensure that the enterprise agencies set ambitious and stretching targets.

The Committee will take evidence from the Strategic Board in early 2019 as part of its ongoing budget scrutiny. The Committee will also gather evidence from businesses on the enterprise agencies’ targets and how they are achieved and measured.

Inclusive growth

During 2017/18, Scottish Enterprise spent £19.3 million on ‘inclusive growth’, equivalent to 8% of its total operating expenditure. This included spending on ‘job creation/safeguarding grant support schemes’ and ‘entrepreneurship, leadership and organisational development.’

When asked why they had only invested 8% of their operating expenditure for 2017-18 on inclusive growth, Iain Scott of Scottish Enterprise said that this was due to the way that they have split their business plan headings, ‘but it is not a fair reflection to say that we spent £19 million in that area – far from it’.i

Scottish Enterprise said that ‘since our focus was pushed towards inclusive growth a number of years ago, we’ve been trying to build up the type of evidence that we want to review in that area’, but admitted that ‘we need to do much more on how we generate inclusive growth and how that growth is spread’. They are tracking data across elements of the business pledge for their account management portfolio and will use it as they develop their plan for next year.ii

Scottish Enterprise highlighted that ‘we will make sure that inclusive growth is absolutely embedded in all the conversations that we have with companies at a sectoral level and with our partners’ and that this is linked to other work such as driving productivity and innovation. For example, they described conversations they will have with companies around the business pledge, etc.iii

North Ayrshire Council said there is little evidence locally of an agenda of fair work emanating from national agencies. They noted that:

The approach to inward investment particularly by Scottish Enterprise is very much sector and nationally focused. This often realises enquiries to major areas e.g. cities, central belt. There is little focus on regional opportunities linking to the wider inclusive growth agenda.iv

However, they did acknowledge that Scottish Enterprise has indicated an appetite to explore the regional approach; they recommended that greater focus should be given to directing investment to areas where it can have greatest economic impact on the labour market.v

The Committee was interested in what Scottish Enterprise is doing to address economic disparities and whether it targets local areas that have the highest employment gaps, particularly in relation to inward investment. Steve Dunlop spoke of ‘moving into much deeper partnerships with local authorities through regional economic partnerships’ and having inward investment prospectuses for all the regions.vi They followed up with examples, such as working with companies in receipt of RSA to develop Invest in Youth policies.vii

Some of Scottish Enterprise’s targets are tangible and easy to measure (such as levels of investment secured). However, targets around inclusive growth use words such as ‘companies engaged and supported to develop approaches to fair and progressive workplace practices’. The Committee is not clear whether this means that these companies now have such practices in place, or whether it simply means that they were simply engaged on the matter.

The Committee recommends that the enterprise agencies produce more explicit, measurable inclusive growth targets in future business plans.

Equalities

HIE told the Committee that female ownership of their account managed businesses is 33%, whilst the number that have a female chief executive is only 14% and those in senior leadership positions is 48%.i Scottish Enterprise is now tracking the number of female-led account managed companies which currently stands at 9.5%.ii

When asked about what they were doing to improve diversity in businesses more broadly, HIE responded ‘there is probably a need to do more in some of these areas’ and that they ‘probably need to do some work in relation to disability’.iii

In its operating plan for 2018/19, HIE set out that one of its priorities will be to improve ‘the diversity of business through programmes to encourage female entrepreneurs and young people with ambitious business ideas.'

Similarly, Linda Hanna of Scottish Enterprise said ‘diversity is something that we do not do enough of, if I am honest, and we need to do more of it. We have been looking at how we do that and how to make it much more pervasive in what we do’. She went on to say, ‘we are not doing enough in disadvantaged and disabled areas and we know that we need to do more.'iv

However, Scottish Enterprise again highlighted inward investment from Barclays to target 340 new jobs for disadvantaged and disabled recruitment.v This is out of a total of up to 2,500 jobs. Scottish Enterprise has introduced the Training Disadvantaged Workers and Workers with Disabilities Scheme, aiming to encourage investment in training by companies in Scotland and to promote the recruitment of disadvantaged workers and workers with disabilities.vi

The Committee notes evidence from both enterprise agencies that they could do more to address diversity in businesses across Scotland. The Committee recommends that they set clear, measurable diversity targets in future business plans. These targets should be broad to include, but not be restricted to, the full range of protected characteristics.

Conditionality

In its 2018/19 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government committed to making Scotland ‘a world-leading Fair Work nation’:

‘We will publish a Fair Work Action Plan by the end of 2018 that will set out the next steps we will take to embed fair work practices in Scottish workplaces by 2025. As part of this we will introduce fair work criteria, including paying the Living Wage, excluding exploitative zero-hours contracts and being transparent on gender-equal pay to business support grants through Regional Selective Assistance and other large Scottish Enterprise job-related grants, starting with grants offered in 2019-20.’i

This approach has been welcomed by the STUC,ii and Scottish Enterprise said that it is working with the Scottish Government on how this will be taken forward.iii

When asked about conditionality, Steve Dunlop said:

With RSA, the sense is of a different direction of travel in respect of us being much more articulate about what we want in return for public investment. You will see that for our major grants next year there will be more thought given to what we expect in relation to levels of conditionality. We will drive that forward. We will work with the business community.iv

However, he went on to say that the best results derive from positively influencing ‘rather than by using sticks’.v Linda Hanna said that thinking about conditionality too early ‘can switch lots of companies off’.vi

Matt Lancashire of SCDI indicated that businesses are open to considering conditionality:

If we are talking about things leading to more conditionality in business support for quality jobs, we are already on that path anyway as businesses begin to change and begin to value their employees more in Scotland. It is no surprise that Governments listen in to those discussions about how we can create fairer and more equal quality jobs in the workplace. I think that businesses are ready to discuss that, to listen to those views, and to look at the rewards that there might be from that in respect of increased productivity. We cannot just nosedive straight into that area without a broader conversation with business to understand where we are now.vii

When asked about action on the gender pay gap, HIE spoke of promoting the benefits of a fair work agenda, ‘rather than looking at any negative or conditionality approach’.viii However, patterns of occupational segregation and the gender pay gap are more pronounced in the region than in Scotland as a whole. They are monitoring gender balance in business leadership and programme participation.ix

The Committee notes the assertion from the Enterprise Agencies that positive influence is effective. However, with the focus on conditionality in the Programme for Government, it appears that a shift in approach will be required to achieve this. The Committee will scrutinise progress in implementing this aspect of the Programme for Government as part of its ongoing budget scrutiny.

Enterprise agencies and job quality

The Committee is also examining the role of the enterprise agencies in supporting and growing good quality employment.

The legislation establishing Scottish Enterprise, as we know it, set out its fundamental role as ‘furthering the development of Scotland's economy and in that connection providing, maintaining and safeguarding employment’.i

HIE have the broader role of ‘preparing, concerting, promoting, assisting and undertaking measures for the economic and social development of the Highlands and Islands.'ii

In its 2018/19 Business Plan, Scottish Enterprise commits to consider how to help tackle inequality, whilst improving employee wellbeing and productivity. According to Scottish Enterprise; ‘this inclusive approach to growth means we need to think and act very differently about where we invest resources and will be a key feature of the transition we make as an organisation over the coming year.’iii

When asked about the quality of jobs it is creating, Scottish Enterprise they have set a specific financial benchmark of salaries above £38,000.iv

According to HIE’s performance report, ‘an estimated 981 jobs are expected to be created or retained in the region, as a result of the organisation’s investments during the year; 139 of these in fragile areas.’v

HIE told the Committee that 981 jobs were counted against their performance measures for 2017/18. They have met all their job creation targets over the past five years.vi

When asked about the quality of jobs created as a result of its interventions, HIE said that they have set a measure to ensure that the average wage of the jobs that they support is higher than the regional average wage but that the jobs they support are ‘a mix’, with support going to higher paid jobs, whilst ‘there might be support going into areas where there is lower pay, but where the jobs are absolutely critical’ to ‘sustainable communities’ in the region.vii

However, STUC said ‘too often the value of investment is considered simply by the number of jobs created in a local area, with assessments of the quality of work, the security of work or the level of wages on offer to workers not prioritised. Greater emphasis must be placed on more long term issues of job quality so as to ensure a genuine focus on inclusive growth is maintained’.viii

They argued that business support is ‘routinely going to companies that have very low outcomes. We have only to look at the grants for Amazon, for example.’ Although they were encouraged by the recent measures in the Programme for Government.ix

HIE highlighted difficulties in attracting skills to the region where larger numbers of jobs are being created:

The real challenge for delivering the Liberty project is around attracting the skills base to Fort William without having a detrimental impact on other key businesses in the area that already face some skills challenges.x

The Committee will examine the regional challenges in attracting skills as part of its forthcoming inquiry on skills.

Brexit

The Committee was surprised that Brexit barely featured in the business plans of the enterprise agencies.

When asked about Brexit, HIE said many companies see recruitment and retention as significant challenges, and the proportion of businesses with concern about skills and challenges is ‘even higher in sectors such as tourism and food and drink, which are heavily reliant on migrant workers’. HIE said that many businesses are looking at productivity investment opportunities to improve their own resilience. They also highlighted opportunities arising from Brexit, for example in the tourism sector and looking at exporting to growth economies outwith the EU. i

Similarly, Scottish Enterprise said, ‘we need to be able to help businesses respond to every challenge that Brexit brings, but there will also be opportunities. We need to be really nimble and to take advantage of those opportunities quickly’.ii

Impact of automation

The possible conflict between productivity gains from automation and impact on employment is summarised by North Ayrshire Council:

the budgets for both HIE and SE have considerable focus on supporting the acceleration of business growth. It is expected that increases in turnover will demand an increase in staff levels. This however is not always the case and with similar focus on innovation and new technologies a challenge exists on resources to help support more traditional regional economies.i

SCDI called for the creation of a Fourth Industrial Revolution Commission and said, ‘good things are happening across industry, the public sector and the agencies, but the problem is that they are not joined up.’ii

They suggested that there is a role for the enterprise agencies in being proactive:

Scottish Enterprise, SDI and others need to help to bring investment into Scotland so that it can develop as a front-runner in the AI digital revolution. We do not want to be left behind; we want to be at the cutting edge of that revolution so that jobs are retained and created. There is certainly a role for SDS to play in providing support for retraining, and work-based learning is a critical element of that.ii

STUC highlighted the need to look at in-work training and a framework that allows employers and workers to drive that change.iv

HIE said that improving investment in automation is one of the keys to the challenge in skills and that there is ‘definitely scope for greater investment in automation.'v They believe that leadership on automation ‘needs to come from business.'vi

Steve Dunlop of Scottish Enterprise said that ‘as things move so quickly ahead of us and change and have massive impacts, we, as this family of agencies, are beginning to collaborate more deeply.'vii

The Committee would expect to see more about planning for the fourth industrial revolution in future business plans.

Annex A

Evidence on Community and Locally Owned Energy

Background

The Scottish Government has set targets of 1GW of community and locally-owned renewable energy by 2020, 2 GW by 2030, and for at least half of all newly consented renewable energy projects to have an element of shared ownership by 2020.i

Community and Renewable Energy Scheme (CARES) was established in 2011 to encourage local and community ownership of renewable energy across Scotland. It is delivered on the Scottish Government's behalf by Local Energy Scotland.

The main funding streams for new applicants are:

CARES Enablement Grant – Up to £25K where the value of the grant will be capped based on innovation or scheme complexity and can be used to fund feasibility for energy systems or renewable energy projects, investigation of shared ownership opportunities or work to maximise the impact from community benefit association with renewable energy projects.

CARES Development Loan – Up to £150K (10% interest rate) can be provided for projects with a reasonable chance of success. The loans can include a write-off facility that allows development risk to be mitigated by allowing the applicant to apply to change the loan to a grant should the project be unable progress.

CARES Innovation Grant – Up to £150K to either fund innovation activity or improve the viability of projects by grant funding elements of the project.ii

This is a summary of evidence received by the Committee on community and locally owned energy.iii

Scottish Government’s approach to financing and supporting community and locally owned energy

Aberdeenshire Council believes that the CARES scheme has been ‘very effective’ in enabling communities to bring forward renewable energy schemes. They explained that CARES removes the majority of the financial risk associated with the pre-planning development stage of a project giving a community group (or rural business) the confidence to progress a scheme:

From the Scottish Government’s viewpoint this is relatively low financial cost and low risk, as the majority of schemes will be successfully completed, with the original CARES investment being repaid together with profits benefiting the local community.

They also highlighted the Renewable Energy Investment Find (REIF) (now EIF) as ‘vital in providing early stage project development funding’ and said that competitive funds such as the Local Energy Challenge Fund work well in bringing forward large scale and innovative energy projects but that care must be taken to allow sufficient time for projects to develop:

It is unreasonable to expect a six million pound project to be completed from scratch in a twelve month time frame as the Energyzing Insch project found out to its cost.

UNISON Scotland welcomes initiatives under way but wants to see much greater support for community and locally owned energy. They argued that there is ‘potential for a major expansion in community energy’. In particular, they have been calling for local authorities to get involved in municipal energy, generating electricity, managing distribution grids and running energy efficiency schemes and retail sales.

The key challenge for both community and locally owned energy, according to North Ayrshire Council, is to provide a clear route to market in a subsidy-free environment for renewable projects. The focus of the CARES programme has been for community owned projects; they believe that it would be beneficial if local authorities could have the same level of access with the need for match funding.

The key challenge for both community and locally owned energy, according to North Ayrshire Council, is to provide a clear route to market in a subsidy-free environment for renewable projects. The focus of the CARES programme has been for community owned projects; they believe that it would be beneficial if local authorities could have the same level of access with the need for match funding.

Unite the Union welcomes the community renewable energy schemes receiving support but argues that there should be a shift in the control of energy away from large multi-national companies towards the re-nationalisation of the energy market in a way that protects the jobs, terms and conditions of workers presently employed across the sector.

Is there adequate funding to hit the 2020 target of 1GW of community and locally owned energy by 2020 and 2GW by 2030?

UNISON Scotland do not believe that there is adequate funding to hit the 2020 target of 1GW of community and locally owned energy by 2020 and 2GW by 2030. They want to see increased funding and early investment. They argue that there should be a ‘Just Transition’i to a low carbon economy and for the new Just Transition Commission to assess the range of types of public investment required to drive the transition, aligned with an industrial strategy for Scotland. They believe that the Commission should be put on a statutory footing.

North Ayrshire Council is delivering the Social Housing Solar PV retrofit project to install rooftop solar on up to 500 properties in their housing stock that will lead to an aggregated installed capacity in the region of 1MW. This complements the solar PV arrays installed across many of their schools and corporate buildings (total installed capacity of c.1.5MW) in addition to a biomass boiler programme (total installed capacity of over 4MWp) at 13 educational properties.

North Ayrshire Council said that many of these installations are unlikely to have existed in the absence of suitable support systems to offset the heightened costs over more established (and higher carbon) alternatives.

They highlighted a case in which they have received planning consent for a 5MW solar farm but are having to revisit the business case as solar PV is ‘not considered to be innovative it is unlikely to attract capital funding from CARES or Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme (LCITP)ii, despite ‘the potential to add innovative measures such as battery storage’. With capital funding currently aimed at demonstrator and innovative projects, they argue that if funding were made available for standalone projects then this would help to reach the 1GW target in 2020.

Which technologies (heat and/or electricity) have the most potential to transform community and locally owned energy, and are resources being adequately targeted?

UNISON Scotland believes that there needs to be a mix of technologies, including pilot schemes for a range of ways of using hydrogen. They highlighted the Levenmouth Community Energy Project, which utilises renewable electricity produced locally by a wind turbine and solar panels to create hydrogen from water. They believe that such projects should be supported and that there is a need for investment in innovative pilot hydrogen schemes.

UNISON Scotland said that local authorities should have the power to take direct responsibility for implementing district heating plans as part of a municipal energy plan. They highlight that this would require funding from the Scottish Government, specifically increased funding support for municipal district heating schemes and for community energy, with incentives for councils to ‘move quickly on this’.

North Ayrshire said that Air Source Heat Pumps (ASHP) to social housing stock could have potential in areas which are off the mains gas and rely on solid/liquid fuels, which are often transported by road. They explained that uptake of this technology has not been widespread within individual dwellings but that there are a number or large-scale heat networks that are expected to use heat pumps. They can also envisage the benefits of domestic battery storage when used with passive generation such as Solar PV.

Aberdeenshire Council said that electricity generating projects are still the simplest and easiest for a community to progress; reductions in the Feed-in Tariff, which is due to end completely in April 2019, have meant that it is very difficult to make wind and hydro projects financially viable. They agreed that there may be scope for Solar PV projects but that heat projects would be harder to implement, with higher risk, and would probably require setting up an Energy Service Company.

Organisational structures and benefits

Role of local authorities

As outlined above, UNISON Scotland believes that local authorities should be encouraged and funded to take the lead, potentially with support from the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) and, perhaps, from the new publicly owned energy company. They believe that SNIB should provide large-scale investment to support a ‘just transition’, including for a national programme of district heating.