Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee

Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee Legacy Report - Session 5

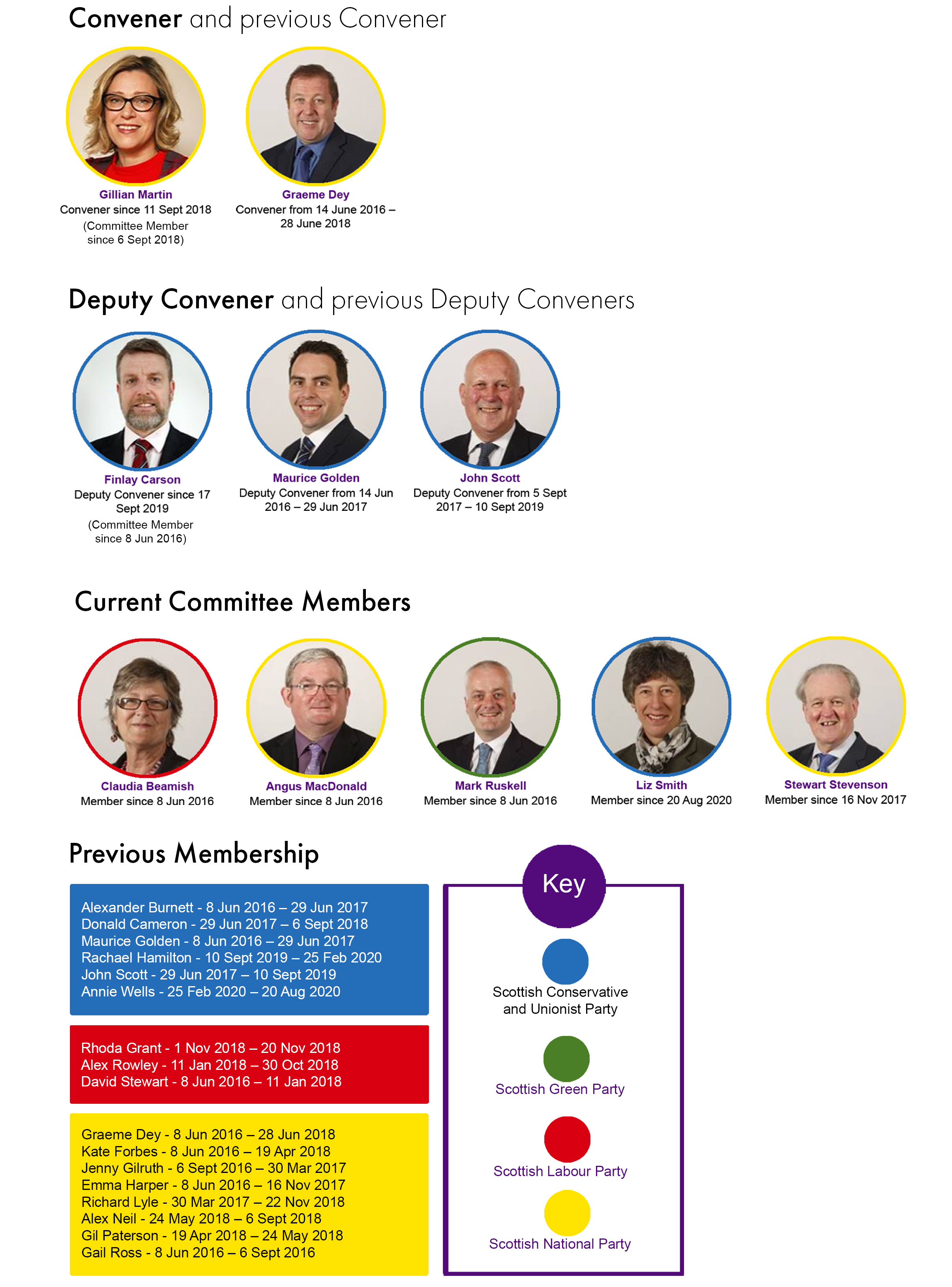

Committee Membership

Introduction

This report sets out the focus of the work of the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee (the Committee) over session 5. It seeks to capture the impact of that work, lessons learned in the course of the Committee’s scrutiny, and sets out the Committee’s view on key issues and priorities for consideration by successor committees in session 6. The Committee also sets out its views in relation to future parliamentary scrutiny of the environment, climate change and land reform policy area.

The Committee’s scrutiny over session 5 has been dominated by the impacts of the decision of the UK to leave the EU and the current Covid-19 health pandemic. The policy area covered by the Committee is extensive. Despite the stated intentions of the Committee at the outset of session 5 it is with regret that the Committee notes that some significant areas of policy, such as the ecological crisis and the adequacy of the Scottish Government’s response to this, and a number of other Scottish Government commitments have gone unscrutinised or under scrutinised this session. The Committee notes its frustration that it has been unable to pursue important scrutiny priorities this session.

The Committee considers that the pressures that have developed over this parliamentary session are likely to extend and grow into session 6. The Committee believes that scrutiny of the Scottish Government response to the ecological and climate crisis and its action to deliver a green recovery will form a major part of Parliamentary business in session 6 and will need to be high on the Parliamentary agenda. Committee remits and support for scrutiny will need to reflect this. The Committee highlights that scrutiny in session 6 will be taking place post UK exit from the EU and this will have significant and lasting implications for scrutiny in areas of policy within the Committee’s remit.

Committee activity in session 5

The Committee’s approach to scrutiny

At the start of the session the Committee agreed to take a strategic and prioritised approach to scrutiny, based on the Committee’s scope to influence. The Committee agreed: the principles and focus of its scrutiny; its working practices, how it wished to be supported in its work, and its engagement strategy. This set the strategic framework for the session and the Committee sought to operate within that. Further detail on this is included in Annexe 1. Key areas of work undertaken by the Committee and related outcomes are set out below.

The Committee met 168 times formally over the session for 438 hours and 47 minutes (67% of the time in public) and undertook further significant informal engagement.

Environmental impacts of EU exit

From the outset the Committee sought to understand the environmental impacts of the UK exit from the EU, including whether and how to: ensure the UK’s future alignment with EU environmental standards; replace environmental governance arrangements that depended on EU institutions; replace the EU’s review and enforcement powers over public authorities in the UK; maintain the role of EU environmental law principles in future policy making across the UK, and; how law-making and enforcement powers previously exercised by the EU will be allocated between UK and devolved administrations after exit. The Committee also scrutinised a significant number of EU exit SSIs and SIs along with EU exit related primary legislation, often within constrained timescales. The Committee engaged with other Parliamentary Committees on EU exit including the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee and House of Lords EU Environment Sub Committee, to discuss implications of EU exit for scrutiny of environmental standards, including inter-governmental and inter-parliamentary relationships and frameworks.

The Committee is aware of the constitutional implications of EU exit, particularly the extent to which decisions made by the UK Government may constrain the Scottish Government’s ability to exercise effectively their functions in those areas of law previously in EU competence. The Committee explored this in relation to the UK Internal Market Act 2020, especially the principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination which together seek to avoid internal barriers to trade within the UK, common frameworks and the increasing number of the Scottish Parliament’s legislative powers which are ‘shared’ with UK Ministers. The Committee has highlighted the need for the devolution settlement to keep pace with the constitutional reality of a post-EU UK. Key areas of scrutiny are detailed below.

Environmental principles and governance: The Committee focused on how and what environmental principles would underpin policy and legislation and how environmental governance would be developed to fulfil gaps left by EU exit. The Committee’s work culminated in scrutiny of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill - now Act - which brings environmental principles into domestic law, gives Scottish Ministers powers to keep pace with EU law and establishes a new environmental watchdog – Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS). The Bill was amended to reflect a number of the Committee’s recommendations, contained in its Stage 1 report.

Implications for Scotland of UK Government legislation relating to EU exit: The Committee considered relevant UK legislation, including the UK Environment Bill and the environmental implications of both the UK Agriculture Bill and the UK Fisheries Bill. The Committee raised a number of concerns and questioned why environmental powers in devolved competence needed to be made via UK primary legislation. The Committee also considered the implications of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the Internal Market Act.

EU exit-related Statutory Instruments (SIs) and Scottish Statutory Instruments (SSIs): The Committee considered a large number of regulations that sought to provide legal continuity and ensure the functioning of the statute book following EU exit. Scrutiny involved significant considerations about how EU regulatory systems should be replaced or replicated in Scotland or at UK-level, such as the regulation of chemicals and emissions trading. In scrutinising the regulations, the Committee raised serious concerns including, in relation to the lack of notice of forthcoming SI notifications, poor quality of accompanying information, errors, including in relation to how powers are conferred, short timescales for consideration, and UK and Scottish Government reporting on the final regulations. These concerns remain outstanding.

Post-EU exit replacement funding arrangements for key sources of environmental funding including post-CAP rural support, LIFE funding for conservation programmes, Horizon research funding, and structural funds. The Committee asked Parliament’s first Citizen’s Jury to explore how funding and advice for land management should be designed to help protect Scotland’s natural environment. The Committee commissioned follow-up research to support consideration of the recommendations. The Committee pursued this in its green recovery and 2021/22 Budget reports and recommended the Scottish Government engage with the UK Government to ensure that the UK Shared Prosperity Fund is delivered from the end of the transition period and designed to further environmental objectives.

Common Frameworks and the approach to developing them. The Committee raised concerns in 2020 about the pace of progress in the agreement of new common frameworks and sequencing issues. A lack of information about the timing of frameworks has made, and is likely to continue to make, the planning of scrutiny, and ensuring effective, impactful scrutiny, challenging.

Green Recovery

Green recovery

The Committee held an inquiry in 2020 to identify key opportunities for the economic recovery from the Covid-19 health pandemic to be aligned with sustainable development goals – a ‘green recovery’. The Committee concluded that Scotland needs to lock in positive behaviours, front-load investment in the low-carbon solutions and build resilience through valuing nature. The Committee also emphasised the need to tackle the implementation gap, where solutions have already been identified but not applied, and ensure all parts of Government and the wider public sector are contributing towards strategic goals. In its 2021-22 pre-budget report the Committee focused on how spend could be aligned to strategic goals on green recovery, climate and the ecological crisis, improving resilience and building a wellbeing economy. While the response of the Scottish Government was broadly positive, the Scottish Government did not respond to a number of the specific recommendations in the report. The Committee highlighted this in its report on the Climate Change Plan update (CCPu).

Climate Change and Net Zero

Climate Change and Net Zero

The Committee spent a significant part of session 5 engaged in climate change scrutiny. Key work included:

Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill 2019 – now Act: The Committee scrutinised and reported on the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill – now Act 2019 at Stage 1 and Stage 2. The Act set a net zero target for the first time, for 2045. The Committee agreed with the introduction of a net-zero target. The Committee called for greater urgency of action in tackling climate change across all parts of Government, across the public and private sectors and by individuals, to deliver the transformational structural change required. A number of the Committee’s recommendations were included in the 2019 Act, including: an extension of the period for parliamentary scrutiny of Climate Change Plans (CCPs); an annual reporting requirement on the progress of CCPs in meeting emissions targets; and embedding just transition principles in the CCPs. The Scottish Government committed to produce an updated climate change plan, as recommended by the Committee. During the course of the Bill’s journey through Parliament, the Scottish Government set up the Just Transition Commission (the Commission), established for a two-year period to provide independent advice to Scottish Ministers on the long-term strategic opportunities and challenges relating to the transition to a net-zero economy. Interim reports from the Commission have informed the Committee’s scrutiny, including ‘Advice on a Green Recovery’ (July 2020). The Commission will produce their final report in March 2021.

2017 Climate Change Plan (CCP) and 2020 update (CCPu): The Committee led scrutiny of the plans in collaboration with the Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee, the Local Government and Communities Committee and the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee. In its most recent report, the Committee made a number of recommendations, including in relation to the ambition of the updated plan, the balance of effort, key assumptions, behaviour change, key sectors and governance. The Scottish Government provided an initial response in the parliamentary debate on 9 March 2021. The Committee is seeking a detailed response to each of its recommendations.

Climate change adaptation: The Committee scrutinised Scotland's first and second Climate Change Adaptation Programmes and the Climate Change Committee’s independent assessment of these. The Committee wrote to relevant parliamentary committees to bring this assessment to their attention and recognised the need for further resilience in its green recovery work. Scope for further work was limited by legislative pressures on the Committee’s work programme.

Effective climate change scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament: The Committee considered the effectiveness of climate change scrutiny across the Parliament, following its work on the Climate Change Bill. The Committee considered how climate considerations can be embedded into the decision making and culture to achieve a net zero/zero emissions Parliament and ensure that climate considerations are effectively embedded in parliamentary scrutiny. A summary of the Committee’s recommendations is included in Annexe 2.

Committee engagement on COP26: The Committee agreed that its principal focus for COP26 would be examining how parliaments can contribute to solutions to the climate crisis and effectively hold governments to account. The Committee agreed a series of key objectives for engagement with COP26 and engaged with sister committees across the UK on opportunities for a collaborative approach, including holding a joint informal meeting in March 2021. The Committee also explored the Scottish Parliament’s and Scottish Government’s plans in relation to COP26. Detail on proposals for further work is contained later in the report and in Annexe 8.

Marine Environment

Marine inquiry: The Committee took a strategic approach to its work on the marine environment. This focused on issues arising from the review of the National Marine Plan, in particular progress in the formation of Marine Planning Partnerships (MPPs) which have delegated powers to develop Regional Marine Plans (RMPs). The Committee also considered the health of Scottish seas, and the extent to which duties to protect and enhance the marine environment are being delivered through systems such as marine planning and licensing. The Committee examined progress in establishing the first MPPs in Shetland, Clyde and Orkney and their work towards publishing Scotland’s first RMPs. The Committee visited each region, meeting with stakeholders involved in regional marine planning and members of the community. It also commissioned research exploring international comparisons of the governance and implementation of marine planning. The Committee made a number of recommendations, including greater leadership and guidance from central government and Marine Scotland to increase momentum and ensure that opportunities to engage with expanding marine industries such as offshore wind, aquaculture and marine tourism are not missed. The Committee also emphasised that regional marine planning has the potential to be a key driver for delivering a Green Recovery and sustainable economic growth in Scotland's coastal communities.

Aquaculture inquiry: The Committee conducted an inquiry on the environmental impacts of salmon farming and wrote to the Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) Committee in March 2018 with its conclusions. The Committee’s work was based on a Review of the Environmental Impacts of Salmon Farming in Scotland from SAMS Research Services jointly commissioned by the Committee and the REC Committee, in 2018 to inform the work of the committees. The Committee’s conclusions included: that the status quo is not an option and that the current consenting and regulatory framework, including the approach to sanctions and enforcement is inadequate to address the environmental issues. The Committee considered: an independent review of the sustainability of growth of the sector is necessary; significant gaps in knowledge, data, monitoring and research around the risk the sector poses to ecosystems need to be addressed, and; an ecosystems-based approach to planning industry growth and development in the marine environment, identifying the carrying capacity is also necessary. The REC Committee reported its findings in November 2018 and held a short follow-up inquiry on the issues in November 2020, which followed up the findings from both committees.

Freshwater Environment

River gradings and protection for wild salmon: On an annual basis the Committee considered the river gradings and the protection afforded to wild salmon. The Committee hoped to undertake further work on the freshwater environment and wild salmon but was unable to progress this due to legislative pressures on the Committee’s work programme.

Biodiversity

Progress to 2020 biodiversity targets: The Committee undertook a biodiversity inquiry, focusing on progress towards Scotland’s Biodiversity 2020 Route Map, on priorities for biodiversity funding, and on interim progress reports to 2020 Aichi biodiversity targets. The Committee raised concerns with the Scottish Government that Scotland was not on track to meet the 2020 Aichi targets, and asked the Government to confirm what is being done. Publication of a 2019 progress report in February 2021 shows Scotland is only on track to meet 9 out of 20 Aichi targets and the most recent Scottish Government update to the Committee on biodiversity work, stated that “there is more to be done to improve the condition of biodiversity in Scotland”.

Biodiversity expertise and data: During this session the Committee explored how biodiversity expertise and the provision of biodiversity data is supported. The Committee heard from research institutes that Scotland is losing biodiversity scientific expertise. The Committee repeatedly called for the establishment of a dedicated centre of expertise on biodiversity - to play a role as a neutral focal point and higher-profile science-policy interface - driving research and providing support mechanisms in areas such as data sharing. In November 2020, the Scottish Government announced its intention to establish a Centre for Expertise on Biodiversity.

The Committee had hoped to undertake further work on biodiversity but this was limited by legislative pressures on the Committee’s work programme.

Deer Management

In 2016, NatureScot (then SNH) published a report on Deer Management in Scotland which was triggered by an inquiry undertaken into deer management in Session 4 by the Scottish Parliament's Rural Affairs, Climate Change and Environment Committee. The Committee considered the NatureScot report and held a debate on deer management in 2017, setting out a series of recommendations and suggested that the Government convene a working group to consider issues. Following the Committee’s recommendations an independent Deer Working Group was subsequently appointed by Scottish Ministers to recommend changes to ensure effective deer management in Scotland that safeguards public interests and promotes the sustainable management of wild deer. The Group submitted its final report to the Scottish Government in December 2019. The Committee been concerned about the slow rate of progress and has been awaiting a response from the Scottish Government. Given the significance of this issue, would expect it to be a priority for session 6.

Animal welfare

The Committee scrutinised the Animals and Wildlife (Penalties, Protections and Powers) (Scotland) Bill – now Act 2020. This increases penalties for serious animal welfare and wildlife offences. In its Stage 1 report the Committee supported the proposed increases and explored issues around enforcement, in particular in relation to wildlife crime, recognising that penalties form part of the solution and sufficient resources and collaboration are required to detect wildlife crime. As part of that discussion question were raised in relation to the potential for consolidation of legislation on animal welfare. The Committee also scrutinised the Wild Animals in Travelling Circuses (Scotland) Bill – now Act 2018, which made it an offence for circus operators to use wild animals in travelling circuses, and the draft Prohibited Procedures on Protected Animals (Exemptions) (Scotland) Regulations 2017 relating to tail shortening in dogs. Pressures on the Committee’s work programme have constrained significant further work in this policy area this session, including work on a Member’s Bill on the licencing of dog breeders.

Wildlife crime

The Committee scrutinisedthe Animals and Wildlife (Penalties, Protections and Powers) (Scotland) Act 2020 during this session which increased penalties for serious wildlife offences. This followed an independent review of wildlife penalties which made a number of recommendations in 2015 (‘the Poustie review’). In its Stage 1 report on the Bill, the Committee supported increased penalties proposed for wildlife crime, but stated that penalties form only part of the solution to addressing wildlife crime, and there must also be sufficient resources allocated to the detection of wildlife crime.The Committee also heard calls to extend the powers of the SSPCA in relation to wildlife crime to support efforts to detect and prosecute wildlife offences and agreed that in some situations the SSPCA’s expertise could potentially be used more effectively by expanding their powers. The Committee has also scrutinised annual wildlife crime reports, considering ongoing issues in relation to persecution of birds of prey and other wildlife offences. However, due to pressures on the Committee’s agenda it did not scrutinise the most recent annual report.

Circular economy

A key aspect of the Committee’s work in relation to the circular economy was its consideration of draft regulations to establish a deposit and return scheme (DRS) in Scotland in 2019. Regulations were passed in 2020. The Committee welcomed the expected environmental impact DRS will have and was supportive of the Scheme being as comprehensive as possible. The Committee has raised concerns recently in its consideration of the draft Climate Change Plan update that there are Scottish Government concerns that DRS in Scotland could be undermined by UK internal market legislation. More broadly, the Committee expected to scrutinise primary legislation on the circular economy in 2020 but this was delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic. The need for Scotland to transition to a circular economy was raised frequently during the Committee’s green recovery inquiry, with stakeholders highlighting potential for jobs e.g. in reprocessing. A circular economy was also considered by the Committee in its report on the updated climate change plan. The Committee made a number of recommendations: including that the next iteration of Scotland’s Economic Strategy should be brought forward and built on the concept of a net zero, circular and wellbeing economy; an expansion of the Zero Waste Scotland Circular Economy Investment Fund, and; a circular economy approach to procurement policy and practice. The Committee considers that action to tackle Scotland’s consumption emissions, through robust circular economy policies, will be critical.

Air quality

The Committee conducted an air quality inquiry in 2018. In its report the Committee raised concerns about the pace of action on the ground on air quality and recommended that Clean Air for Scotland Strategy (CAFS) was kept under review to ensure that it remains fit for purpose, including the protection of human health. The Committee also made recommendations to support the progress of Low Emission Zones (LEZs). The Scottish Government went on to commission an independent review of the CAFS which was published in 2019. The Government consulted on a revised strategy in 2020 with the new strategy expected to be published in early 2021. The Committee had hoped to return to scrutinise the progress in implementation, but unfortunately it did not have the time to do this in Session 5.

Land Reform

Land reform has not formed the most significant part of the Committee’s scrutiny this session. The Committee took evidence, considered and reported on the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 (Register of Persons Holding a Controlled Interest in Land) (Scotland) Regulations 2021. These were produced under a requirement of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 to make regulations requiring information to be provided about persons holding a controlled interest in land and for that information to be recorded in a public register. This requirement was added to the Act on the recommendation of the previous Committee to provide transparency and traceability around land ownership. The Committee agreed that people in Scotland should know who owns the land and who benefits from that ownership, and made various recommendations about the functioning of the system and ensure that members of the public or interested stakeholders can access required information at a single point. The Committee also considered the Right to Buy Land to Further Sustainable Development (Eligible Land, Specified Types of Area and Restrictions on Transfers, Assignations and Dealing) (Scotland) Regulations 2020. These regulations brought into force Part 5 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 which created a community right to buy land for the purpose of furthering sustainable development. In its report on its green recovery inquiry, the Committee highlighted that Scotland’s land reform process has created opportunities for communities to build resilience through diversification of land use and to create high quality, permanent jobs. The Committee agreed that community ownership has a vital role to play in a just transition to net zero emissions and in the green recovery by diversifying how natural and built assets are owned and used. The Committee also approved the appointment of Scottish Land Commissioners and the Tenant Farming Commissioner, as provided for in the Land Reform Act 2016, which established the Scottish Land Commission and considered and reported on re-appointments to the Scottish Land Commission.

The Scottish Crown Estate and Scottish Crown Estate Bill

The Committee considered the Scottish Crown Estate Bill – now Act 2019. This established Crown Estate Scotland (CES) to manage land and property owned by the Monarch in right of the Crown in Scotland. A key recommendation of the Committee at Stage 1 was that managers of CES assets should be required to operate in a way that is likely to contribute to sustainable development. The body has now published a Plan for 2020-2023 setting out a commitment to “environmental wellbeing, include protecting natural capital”. The Committee took evidence from CES in 2019 as part of its marine inquiry. CES told the Committee that, as a new organisation, it wants to be proactive about how it delivers sustainable development. Due to its constrained agenda the Committee did not have an opportunity to re-engage with CES on its strategic plan.

The Scottish Parliament’s Environmental Performance

Over Session 5 the Committee has considered the environmental performance of the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body (SPCB), including by scrutinising its annual environmental reports. Latterly, the Committee focused on exploring how the Parliament will work towards net zero and embed sustainable development across the institution. The Committee welcomed SPCB plans to publish a Sustainable Development and Climate Change Strategy early next session and heard that annual targets for session 6 and a delivery plan will be contained within this new ‘Net Zero Ready’ Plan.

Petitions

The Committee’s agenda has constrained its ability to engage with petitions this session. Over the session the Committee considered and closed nine petitions and agreed to keep four open. Detail on these is included in Annexe 8.

Financial scrutiny

The Committee’s financial scrutiny primarily focused on: carbon impacts of capital and infrastructure spending; preventative spending and wellbeing; use of fiscal instruments for environmental outcomes e.g. taxes and levies, and; the role of the budget in the green recovery.

Carbon impacts of capital spend and infrastructure and joint budget review: In response to the Committee’s recommendations to improve how climate change information is presented in the Scottish Budget, and improve budgetary alignment with the climate change plans the Scottish Government committed to work with the Parliament to review budget information in relation to climate change. A joint Scottish Parliament/Scottish Government working group was established to lead and direct this work. In its Stage 1 report on the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill 2019 - now Act - the Committee also recommended that a new methodology should be developed to improve assessment of the contribution made by infrastructure investment to emissions targets. This was endorsed by the Parliament and the Scottish Government started to use broad categories of low, neutral and high carbon - a ‘taxonomy approach’ - to give an indication of the level of alignment of infrastructure investment with climate change goals. The Scottish Government also committed to a increase the proportion of capital spending classed as low carbon in each year of session 5 and commissioned ClimateXChange to develop its taxonomy approach. The Committee considered the draft Infrastructure Investment Plan (IIP) in 2020, the first to have an accompanying Strategic Environmental Assessment which was a recommendation of the Committee.

The Committee raised concerns that the percentage of low carbon programmes was significantly too low, and recommended that the final IIP avoid infrastructure that will lock-in high carbon activities and set out how it has prioritised projects that deliver green jobs. In its green recovery inquiry report, the Committee also supported the inclusion of natural capital in the definition of infrastructure and said “this should lead to a fundamental rethink of how decisions are made on capital allocation”.

Preventative spending and developing a wellbeing economy: The Committee’s work focused on the wider economic and health benefits of environmental spend. During Session 5 the concept of a Natural Health Service has developed and NatureScot have developed an initiative to show how the natural environment can be integrated into health and social care. The Committee recommended that the Scottish Government should: consider what more can be done to extend support to environmental programmes delivering health, wellbeing and economic benefits; develop a greater focus on ‘invest to save’ in the development and implementation of policy and in financial allocations to the environment and natural capital, including through research to demonstrate the cost-benefits of those investments.

The Committee also explored the concepts of a wellbeing economy and recommended that all public expenditure should be consistent with addressing the climate and ecological crises, building a wellbeing economy and delivering a green recovery. The Committee also requested information from the Scottish Government on how it has built wellbeing, climate and environmental considerations into the development of private finance models.

Environmental fiscal reform: The Committee began to explore opportunities for environmental fiscal measures e.g. taxes, levies or charges, as a driver for behavioural change across different environmental policy goals, and as a source of funding to support environmental measures. The Committee agreed that it wished to commission research to review the scope of existing measures and practice elsewhere. Unfortunately, progression of the work was delayed due to pressures of other business, but it is anticipated that SPICe will progress this independently to inform the work of the successor committees.

National Performance Framework (NPF)

Scotland’s National Performance Framework (NPF) is Scotland’s wellbeing framework. It sets out a vision for Scotland through eleven National Outcomes and associated indicators and provides the framework for implementing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). The Committee scrutinised the 2018 refreshed NPF and recommended further consideration of climate change adaptation and mitigation indicators, indicators related to the green economy, land ownership, resource efficiency and air quality. The Committee also raised concerns about adequate time for Parliamentary scrutiny of revised National Outcomes in its conclusions on this – recommending a change to the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015.

Engagement and communication in Session 5

Engagement

Engagement Strategy: The Committee agreed its engagement strategy at the start of the session. Its aims, objectives, outcomes and approaches to engagement are set out in Annexe 3. The Committee specifically sought to hear from individuals with lived experience and from young people and used different methods to do this.

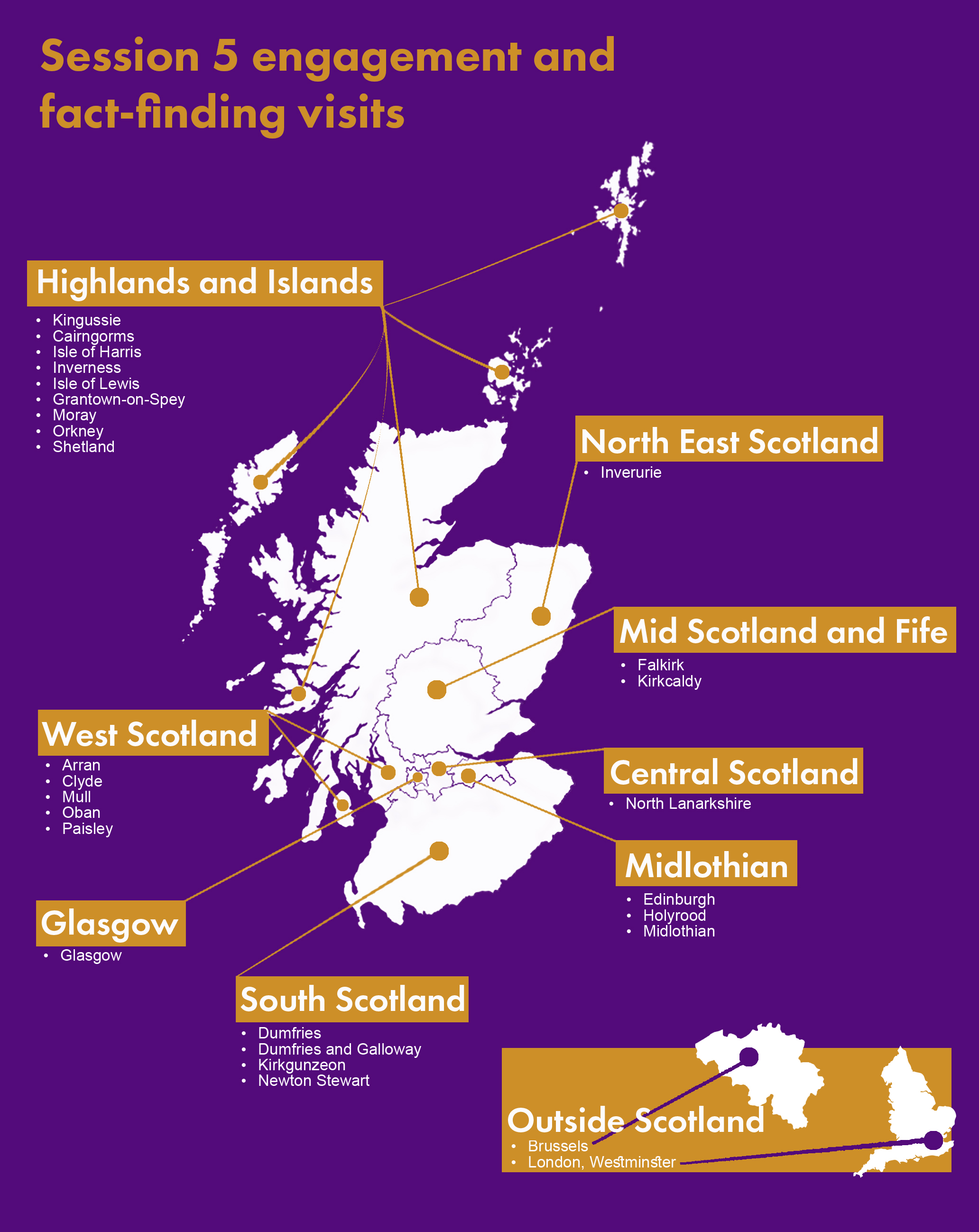

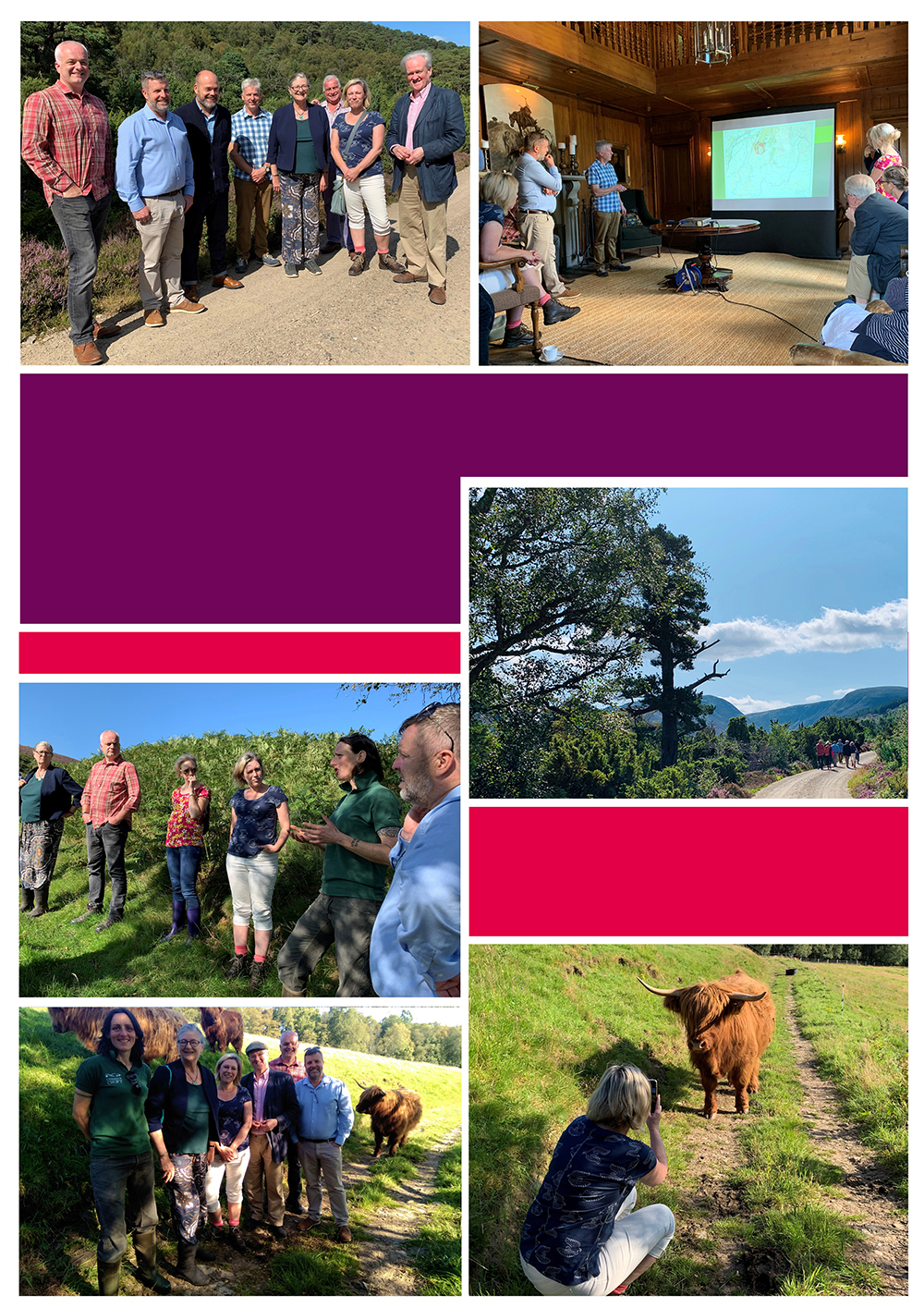

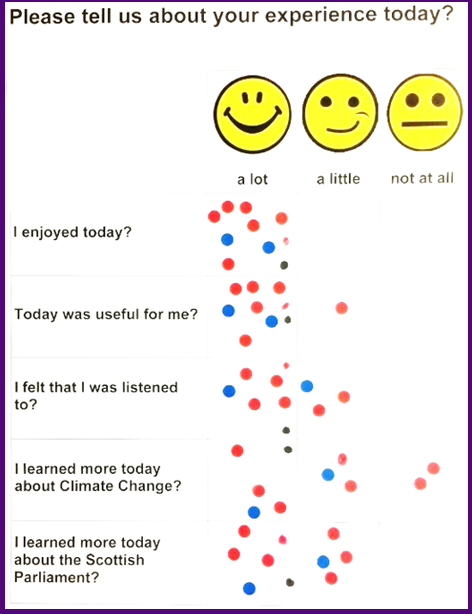

Extending engagement into communities: Using a community development-based approach the Committee sought to work in partnership with voluntary sector organisations though the Parliaments’ Outreach team to co-develop appropriate methods to reach easy to ignore communities, people with lived experience, and to hear from particular people, groups and communities impacted by legislation. Where possible the Committee identified particular groups who may be more vulnerable to the impact of certain legislation or policy and sought approaches to involve these groups in scrutiny. These have included: island and rural communities; older and younger people; people with learning and or physical disabilities; people who are socially and/or economically excluded, and: people who were shielding. The Committee engaged with children and young people on a number of consultations and enquiries. Members also undertook a number of visits to communities and to environmental projects across Scotland. In Annexe 4 the Committee includes a case study of its engagement on climate change to illustrate its approach to engagement this session.

Cross Parliamentary engagement: The Committee engaged formally and informally over the session with sister committees on issues of mutual interest, including the implications of EU exit, common frameworks, EU exit legislation and COP26. Ensuring a more systematic approach to cross parliamentary engagement will be critical in Session 6 as the scrutiny landscape for environmental policy is now more complex.

International engagement: The Committee travelled to Brussels early in the session and engaged directly with the European Commission and third countries, including Iceland, Canada, Norway and Switzerland. The Committee has engaged with, and presented to, the Arctic Circle on human rights and the environment and has engaged with a number of other international bodies and legislatures, including from Norway, Ireland, Sweden and New Zealand and the Nordic Council. The Committee also engaged directly with the UN IPCC and held a joint event with the IPCC and young climate strikers from across Scotland.

Approaches to engagement: A number of approaches were used to effectively inform scrutiny, and to develop a meaningful and sensitive approach to hear from a diverse range of people with lived experience. A summary of engagement activity and approaches used is included in Annexe 5. In addition to calls for views, evidence sessions in formal committee meetings and members travelling to meet stakeholders and communities across Scotland to gather information and scope pieces of work, the Committee engaged with people by:

Using a partnership approach with the third sector, trusted organisations, umbrella bodies, grassroots groups and networks who have: established relationships with individuals and communities.

Setting up external meetings in informal, local, known and trusted settings.

Exploring different means of gathering and presenting evidence, such as staff working to a remit agreed by Members and reporting back, using different methods such as video clips, oral presentation and written report.

Providing advance information and ‘getting to know you’ sessions for individuals and groups, feedback and follow up after engagement.

Presenting information in different and more accessible formats.

The Committee also undertook the first Scottish Parliament deliberative engagement event and the Committee explored using digital platforms to widen the discussion on specific topics and new platforms to manage submissions to call for views. Various enquiries were promoted in Gaelic via twitter and the Parliament's Gaelic blog and the Committee produced executive summaries of some reports in Gaelic.

Communications

The Committee sought to ensure that communications were integral to its work. Media and social media opportunities were identified and incorporated into Committee work from the start. The Committee also agreed its strategy for media and social media involvement from the outset of inquiries, including agreeing goals in advance and identifying the target audience(s). The Committee established and maintained a strong media presence over session 5 which included national, regional and broadcast media, online and social media. Communications focused on topical inquiries and issues of general public interest. This aided the generation of coverage and the overall promotion of the work of the Committee.

The Committee benefited from having an active presence on social media, primarily via twitter. The account grew by over 1000 followers during the course of the session, and now sits just under 4000 – the second-highest of any parliamentary committee. Creating regular, engaging content has been key to this growth including: short clips of witnesses from weekly meetings; convener videos when reports are published; vox pops promoting call for views and expanding the use of podcasts, explainers, threads and the use of Instagram and Facebook.

At a national level the Committee’s meeting with young climate change strikers in a round table discussion generated significant interest. Work on Regional Marine Planning was successful at a local level – generating local print and radio broadcast pieces and the final report generated specialist trade press. A creative approach on social media along with an educational podcast produced excellent results. The Green Recovery Inquiry was a topic of universal interest, generating coverage in all key national papers and national radio broadcast. A podcast was included on the release and was downloaded 260 times with further output on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. This led into promotion of the Committee’s work on the Climate Change Plan Update.

Lessons for scrutiny in Session 6

Impact of EU exit on devolved competence and scrutiny

The Committee considers that the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement is likely to affect Scottish Ministers’ ability to effectively exercise devolved powers and Parliament’s ability to effectively scrutinise in those areas of law previously in EU competence. The extent of this, however, remains uncertain. Scrutinising the implications of EU exit, including related EU Exit legislation, has significantly impacted the Committee’s work programme, as a result of the volume, timing, complexity and lack of detail provided to the Committee. This, alongside the anticipated additional work in relation to environmental governance, monitoring Scottish Government action in relation to keeping pace and engaging with the new reporting requirements contained in the Continuity Act is likely to continue to have significant and lasting impacts on scrutiny, particularly in the environment policy area.

Changes will be required to the Scottish Parliament’s, and successor committees, scrutiny approach. The Committee considers that there is a significant challenge for successor committees in managing and resourcing the additional work required. Successor committees will also need to build strong relationships with sister committees across the UK to underpin effective scrutiny.

Committee remits constraining effective scrutiny

Addressing issues within the environment policy area is often complex and following Cabinet Secretary remits means the scope for committees to scrutinise complex and systemic issues is limited. In session 5 this has resulted in uncertainties over the responsibility for scrutiny, overlaps and gaps in scrutiny and in some cases, some duplication in scrutiny. This has been particularly challenging for this Committee in session 5 where the responsibility for rural economy, environment and land reform policy has been split across committees and where climate change has not been a separate committee responsibility. This has made coherent scrutiny very challenging, as many issues of concern, and the means to address those issues, sit in different committee remits. The additional scrutiny requirements across this portfolio going into session 6 are considerable and include significant additional reporting requirements arising from the recent Continuity and Climate Change Acts. The Committee considers that it will be impossible for one committee to effectively scrutinise across this extensive portfolio. To ensure effective, focused and impactful scrutiny in session 6 the Committee recommends that the responsibility for land management, the rural economy and environment is combined and scrutinised by one committee, as was the case in session 4, and climate change is the sole responsibility of a Net Zero Committee. The Committee suggests the following approach:

Establishing a Natural Resources/Natural Capital Committee

The ecological crisis is recognised as a twin crisis alongside the climate crisis. Effective management of Scotland’s environmental resources (land, fresh-water, marine and air) will be critical in building resilience and addressing the ecological crisis. Similar to the rationale for a Net Zero Committee, establishing a Natural Resources or Natural Capital Committee could work to bring together all aspects of management of Scotland’s natural resources and consider the extent to which policies contribute to the effective management, protection and enhancement of Scotland’s natural resources. This would include: the use of natural resources (including farming, forestry and fishing); biodiversity; environmental governance; land reform, the Land Use Strategy, and the associated regulatory framework. It would also include waste and the circular economy. This approach would reflect a more coherent approach to policy development and scrutiny and would combine issues that sat within the remit of one committee in session 4. It should also provide a greater opportunity for the Parliament to lead scrutiny and undertake ‘own initiated’ work.

Establishing a Net Zero Committee

The Scottish Government has declared a climate emergency and has committed to putting climate change at the heart of government and policy making. The Committee considers that the Scottish Parliament needs to provide a strong commitment to prioritise climate change scrutiny. While we should look to embed climate considerations across the work of all committees via the recommendations for action as proposed by the Committee, we should also set up a Net Zero Committee to lead and drive climate change scrutiny and action in the next session. Establishing a Net Zero Committee in advance of COP26 could have a global impact, encouraging other legislatures to look at how climate scrutiny is organised. The concept of a Scottish Parliament Net Zero Committee was endorsed by the independent Climate Change Committee. A Net Zero Committee could:

Have a clear mandate as a connecting, strategic committee, considering the alignment of key Government strategies across portfolios with net zero goals;

Explore strategic areas such as the wellbeing economy, pursuit of the UN SDGs, alignment of net zero and the National Performance Framework, embedding just transition and human-rights approaches, green recovery, innovation, behaviour change and the circular economy;

Lead and co-ordinate scrutiny of work on climate mitigation: including the Climate Change Plans; the annual monitoring reports on progress with the Climate Change Plan; annual reports on emissions reduction targets; annual reports on consumption emissions and; sectoral delivery of targets;

Lead and co-ordinate scrutiny on the Adaptation Programme: Climate Ready Scotland: Climate Change Adaptation Programme 2019-24 and; the annual Adaptation Programme progress reports;

Lead scrutiny of the climate impact of the Infrastructure Investment Plan;

Lead scrutiny of the Just Transition Commission’s recommendations (from their final report in March 2021) and the Scottish Government response to it;

Lead work with the Government on reporting of the climate impact of the Budget, including the joint Scottish Parliament/Scottish Government Budget Working Group and lead scrutiny of the climate impact of the Budget;

Lead engagement with the people of Scotland in delivering net zero; lead engagement with the Citizen's Assembly, scrutiny of the Scottish Government response to their recommendations and scrutiny of Scottish Government climate change engagement;

Lead committee engagement in COP26. There are significant opportunities and demands for Parliamentary engagement presented by COP26, including opportunities for Committees to explore how COP26 can drive domestic action, showcase best practice, and give Scottish people a platform on climate issues;

Support and take a lead on developing inter-parliamentary climate scrutiny. The CCC has advised that Scotland cannot deliver net zero through devolved policy alone but will also require UK-wide policies to ramp up, and;

Consider the Scottish Parliament response to the climate change targets and the effectiveness of climate change scrutiny across the Scottish Parliament.

Scrutinising systemic and cross cutting issues

Members have recognised the value of working with other Committees in achieving effective scrutiny of complex issues – examples of this include the work of the Committee in relation to: the environmental impacts of salmon farming; the Climate Change Plan; assessing the carbon impacts of the Budget, and; a green recovery from Covid-19. The Committee has also sought to engage constructively with the Scottish Government - examples of this include: the Climate Change (Scotland) Bill and Climate Change Plan; establishing a joint Scottish Parliament/Scottish Government working group on climate change and the Budget, and; early and continuing engagement on EU exit and the implications for environmental governance. Such approaches take more effort from members and from officials behind the scenes (for example clerk to clerk conversations, and SPICe/Legal Services support to multiple committees at once), but the ensuing benefits are clear.

The Committee considers that in session 6 there is merit in the Parliament giving early consideration to how best to facilitate a strategic and systematic approach to scrutiny across committees and to how best to develop collaborative approaches to dealing with challenges such as: climate change; recovery from the health pandemic, and; ensuring a coherent approach to a green recovery – which are the responsibility of all parts of Government and should be at the core of the work of all Cabinet Secretaries and committees. Parliament could also make more use of flexible, short term inquiry and legislative committees, drawing members from across existing committees, where there are cross committee issues that require scrutiny. There may also be scope to make more use of working groups (which the Committee has done this session in relation to legislation that crossed committee remits and in progressing issues such as air quality and deposit and return) and giving further consideration to the use of committee reporters (as the Committee did in respect of Europe and Human Rights). The Committee notes that changes to Standing Orders may be required in order to facilitate this.

Integrating sustainable development thinking into scrutiny

Section 44 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 puts a legal duty on public bodies, including the Scottish Parliament, in exercising their functions, to act in the way best calculated to contribute to the delivery of Scotland’s climate change targets, and in a way that it considers is most sustainable. This means it is incumbent on the Scottish Parliament to build sustainable development thinking in its scrutiny. Progress has been made during this session on how to use sustainable development thinking to improve how the Parliament scrutinises the Government and makes law, and how the Parliament meets statutory duties under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. The Committee has supported the development of a Sustainable Development Impact Assessment Tool, used to frame discussion of policy or legislation and highlight the interaction of socioeconomic and environmental issues. This was used to underpin the Committee’s inquiry work and sustainable development thinking framed our Green Recovery work. The Committee considers that this could be used as a ‘gateway’ assessment tool for successor committee(s), and all committees, to incorporate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals and meet the statutory and other requirements on Parliament to take a human rights approach, and to embed equalities within scrutiny. Changes to Standing Orders may be required in order to facilitate this and the Committee encourages Parliament to give early consideration to this in session 6.

Improving climate change scrutiny across the Parliament

The Committee reflected on what is needed to ensure effective climate change scrutiny across the Scottish Parliament and set out a number of recommendations, particularly in relation to building capacity and ensuring ‘buy-in’ across committees, which it discussed with the Clerk/Chief Executive. Recommendations for action in the short to medium term are included in Annexe 2. This extended the work that began this session on the review of Parliamentary plans and action to support sustainable development and climate scrutiny and consider how climate scrutiny can be prioritised to enable Scotland to move at pace towards net zero. This includes upskilling of members and staff on climate change and sustainable development, how climate and sustainable development considerations are effectively embedded in parliamentary scrutiny via briefing, use of experts and advice, integrating the sustainable development tool into committee scrutiny. The Committee notes that the Climate Change Act creates considerable new reporting requirements and scrutiny challenges that should engage all relevant committees. The Committee considers that a review of Standing Orders should be undertaken as a priority to ensure that climate change and sustainable development scrutiny is given as much prominence as equalities and human rights and scrutiny of sustainable development and climate change is embedded in the work of committees.

A strategic approach to working

The successes of the Committee have been underpinned by the way the Committee has operated and the constructive way members have worked together to achieve shared objectives and agreed outcomes. Members agreed a strategic approach and strategic priorities from the outset, including a strategic approach to engagement and have worked consensually over the session. This is included in Annexes A and C. The Committee has been focused on outcomes and achieving impact and has been able to make strong and challenging recommendations for change, which have been acted on by the Scottish Government. The Committee sought to follow through on work from previous sessions, and from earlier in the session, to ensure that recommendations have been implemented, but this was increasingly challenging. The Committee recommends that successor committees adopt a similarly strategic approach from the outset – identifying key scrutiny priorities for the session. The Committee notes that the ECCLR remit is extremely broad and is significantly underpinned by legislation and the requirement to scrutinise developing policy and legislation as a result of exiting the EU has the potential to dominate the work programmes of successor committees. Committees will continue to be challenged in considering how best to ensure that the legislative burden is balanced alongside time for own initiated work. Successor committees will need to create space for this. Consideration is likely to be needed to enhanced approaches to scrutiny including: the use of sub committees; creation of committees to manage specific bills; shorter inquiries and; more innovative scrutiny approaches, including how best to engage outwith committee meetings.

Approach to scrutinising public sector bodies

Earlier in the session, the Committee was more able to devote time in formal meetings to engage with public bodies in relation to their annual reports or other reporting requirements. Latterly, Committee time to engage with public bodies in this way has been significantly constrained, however, the Committee has sought to engage with public bodies through incorporating engagement across relevant workstreams e.g. on climate change, biodiversity, the green recovery. The Committee considers that the latter approach has potentially been more effective in embedding engagement with the public sector and prioritising key issues. However, the Committee recognises that the role of public bodies is key in the transition to net zero and addressing the nature crisis as well as across other priority areas and considers there is value in a successor committee(s) considering a strategic approach to engagement with public bodies in the next session.

Building knowledge, expertise and capacity in the Committee and across parliamentary committees

Membership of the Committee: There has been consistency in membership of the Committee across parliamentary sessions (and in clerking and other committee support teams) which, in tandem with the small number of members on the Committee, has enabled members and the Committee to build understanding, expertise and strong and cohesive relationships with each other and with stakeholders. The Committee encourages the Parliament to consider establishing committees with a small membership from the outset, enabling members to specialise on one committee/policy area and maintain a consistency of membership over the session, to enhance the effectiveness of scrutiny.

Reporters and Working Groups: The Committee used working groups to engage on specific issues and report back to the Committee – effectively freeing-up time in formal meetings. While this proved to be very useful in developing an understanding of issues and directly hearing a variety of perspectives it was also time consuming for both members and staff. The Committee appointed EU and Human Rights reporters, however, as events developed over the session their role was inevitably constrained. There is scope for committees to give consideration to developing specialist roles and expertise within the committee. Successor committees may wish to consider the value of appointing an EU reporter to take a lead in reviewing regulatory alignment.

Training and resources: The Committee considers that the training and resources available to committees and members has limited the Committee’s approach and capacity for effective scrutiny in session 5. The Committee considers that there are gaps is training that need to be addressed urgently – including in climate and human rights literacy. The Committee makes a number of recommendations – In Annexe 2 – that relate to training (induction and CPD) in session 6. These include ensuring that all members understand the impact of climate change and the legislative and policy framework for addressing the challenges and committees understand climate impacts within their remit, how best to embed climate considerations into scrutiny and the annual reporting and scrutiny cycles.

Use of advisers and experts: The Committee agreed to precede or begin inquiries with evidence from academic/expert panels. Taking a scientific and evidence-based approach to its work has been important in understanding the detail and potential impact of policy and legislation. The Committee has benefited significantly this session from having standing advisers on EU exit and on climate change. The advisers have supported the Committee in developing a strategic approach to its work, providing advice on scrutiny priorities and providing specific briefing. Given the nature of the scrutiny challenges in session 6 the Committee recommends that successor committees appoint standing advisers from the outset. In particular, the Committee sees a significant value in retaining standing advisers to support ongoing work arising from the UK exit from the EU and the climate challenge. The Committee considers that successor committees would also benefit from appointing advisers to support work in relation to challenges such as achieving a green recovery, embedding a circular economy, meeting the biodiversity challenge and ensuring land management frameworks that effectively deliver public goods.

The Committee considers that, similar to the Finance and Constitution Committee, a Net Zero Committee should consider appointing a standing advisory panel to ensure that there is consistent and ongoing support for the work of the Committee on key elements of its work, including on: climate change and the budget; the Climate Change and Adaptation Plans; assessment of the newly introduced annual reports on progress with the Climate Change Plan; emissions reduction targets and consumption emissions, and; the annual reports on adaptation and the assessment of sectoral strategies. The Committee also encourages the Parliament to consider how best to make use of external advisers in supporting committees effectively embedding climate considerations into scrutiny. The Committee considers that a standing panel of advisers with specialist expertise on climate change which committees could draw on when required would be a significant additional support to ensuring effective climate scrutiny by parliamentary committees.

Use of independent research: Much of the most effective work of the Committee this session was underpinned by commissioned research. This was particularly the case with the Committee’s work on the environmental impacts of salmon farming and regional marine planning. When considering priorities for scrutiny the Committee encourages successor committees to actively identify work that could be progressed via commissioned research and opportunities to engage with committees in jointly commissioned research that impacts across committee remits. The process from determining the scope of work through commissioning to conclusion can be lengthy, so early consideration is vital.

Engagement with commissions and expert groups: The Committee is conscious that it has not had the opportunity to engage as extensively as it wished with Commissions and expert groups, including the Scottish Land Commission, the Animal Welfare Commission and the Climate Change Committee. This session also saw the establishment of Environmental Standards Scotland. The Committee recognises the significant expertise that exists in such bodies and recommends that successor committees engage with them early in session 6 and makes more use of them throughout their work.

Direct Parliamentary staff support: In session 5 the Committee significantly extended the use of the Engagement team to support its engagement. This has been a valuable resource enabling the Committee to extend and broaden its scope for engagement, including engaging remotely. The Committee anticipates that this level of support will continue and extend into session 6. The Committee also extended the support of the Legal Services and SPICe teams on its scrutiny of EU exit legislation. This was often on technical and complex issues, within challenging timeframes and often with little or partial information. These scrutiny challenges will remain and extend into session 6. The Committee recognised the value of the additional support, including additional clerking support, and expressed its concerns in relation to ongoing resourcing in two letters to the Finance and Constitution Committee reflecting on the challenges post EU exit, the significance of the level of resources required to give a proportionate and effective level of parliamentary scrutiny and the need for sufficient resource to meet the scrutiny challenge. The Committee stated that it is fundamental that committees have access to sufficient clerking, research and legal resources to ensure parliamentary consideration is meaningful. Looking ahead to support for climate change scrutiny and the scale of the challenge the Committee encourages the Parliament to consider the merits of establishing a climate/sustainable development scrutiny unit to support scrutiny across committees, operating in a similar way to the Financial Scrutiny Unit in SPICe.

Engagement

The Committee was open to using a wide range of tools for engagement and piloting new approaches over the session. Early and direct engagement out-with formal committee meetings has been invaluable in helping members understand the impact of issues and identifying workable solutions. The Committee would encourage successor committees to engage informally and across Scotland to hear from people in their communities. The Committee considers that there is no substitute for this. As the Committee moved through the session the scope for this has been limited as a result of the Covid restrictions and in the final year engagement was entirely remote and digital. Use of virtual meetings is likely to continue to be a feature of engagement and the Committee encourages the Parliament to actively look to improvements in the application of remote technologies to facilitate engagement.

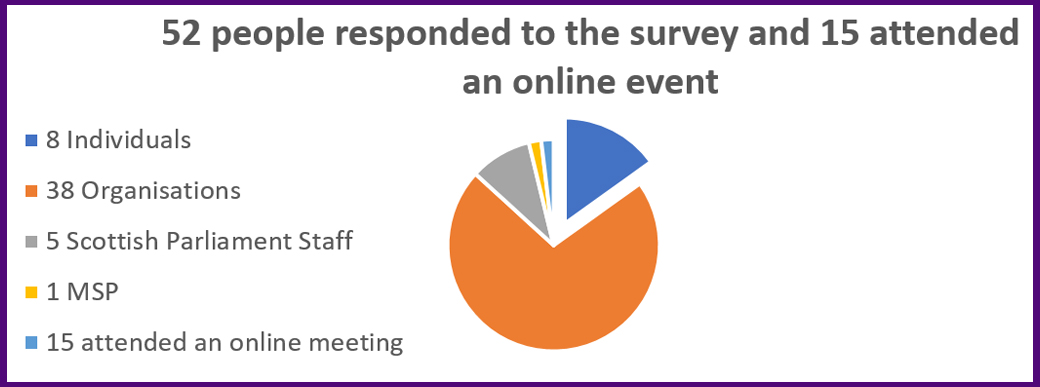

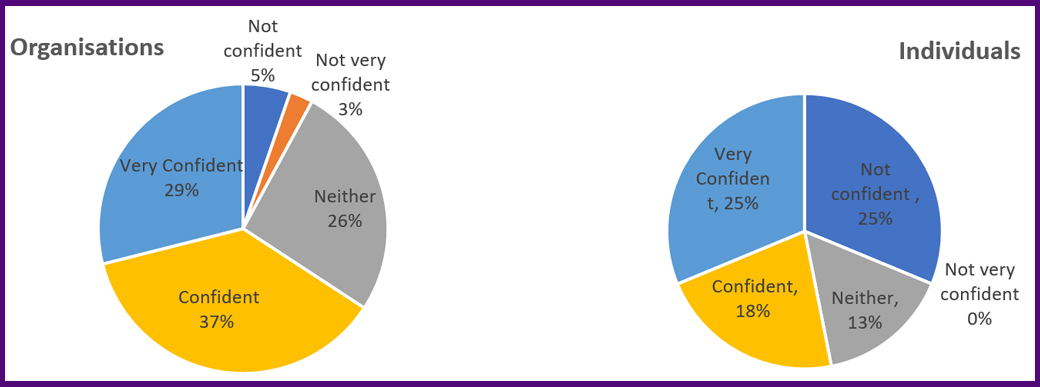

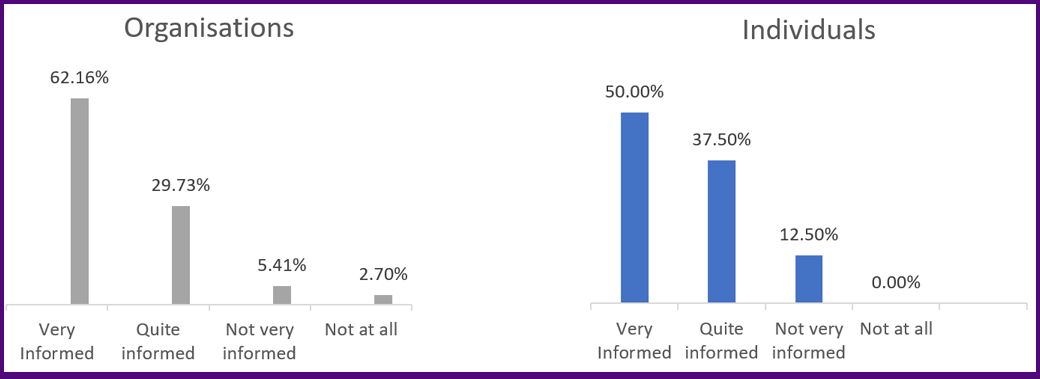

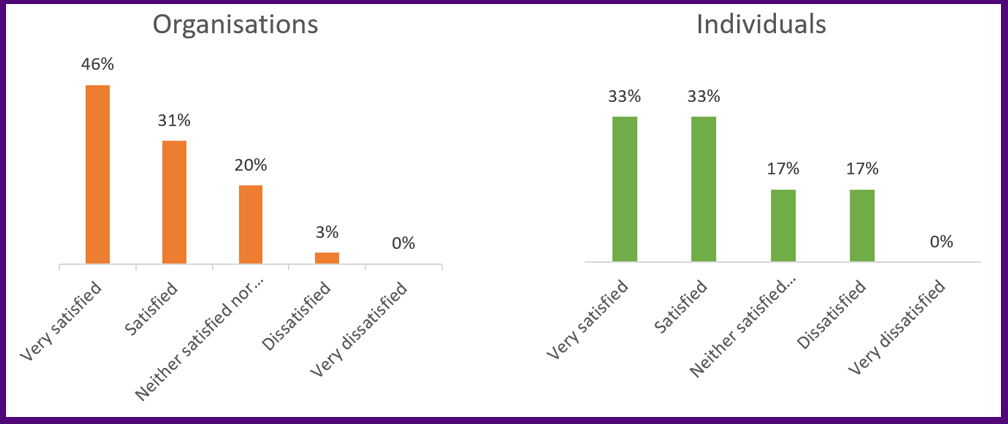

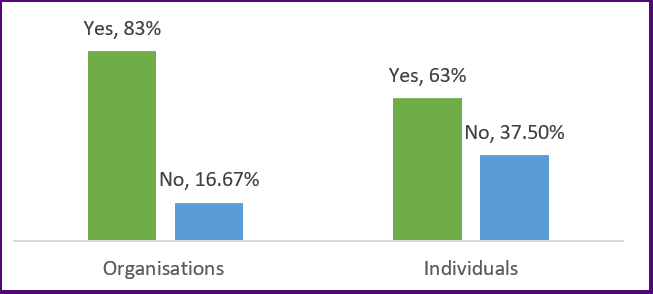

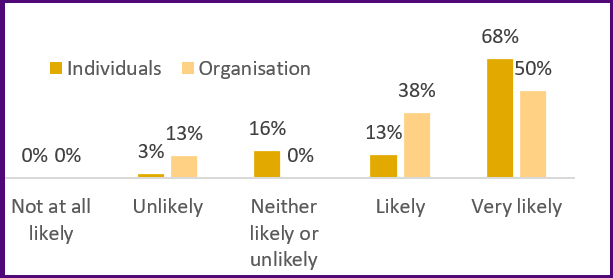

The Committee was interested to understand how effective its engagement had been over the session. The Committee undertook an evaluation of its engagement by sending an online survey to those who had engaged with it and by holding an online meeting. The Committee asked: what has worked well for you in engaging with the Committee this session; what could work better; if parliamentary committees are equipped to respond to the climate crisis/ecological crisis/green recovery and; your priorities for engaging with the Committee next session. 52 individuals, organisations, staff and Members took part in the survey and 15 people attended an online meeting led by the Convener. Feedback was generally very positive and there were some constructive suggestions for improvements. The majority of people felt confident that their views are valued by the Committee, they feel informed, engaged and involved and would engage with Committee again. The key findings are summarised in Annexe 6.

Lessons learned from the evaluation exercise included:

Improve communication - about Committee business, work programme and develop understanding of parliamentary procedures. (i.e. timescales impossible to change);

Clear contact for advice, support and information;

Clear accessible information – for all ages and abilities, provide questions in advance;

Capitalise on digital resources;

Keep up what is working well - continue with visits and outreach, openness and flexibility;

Internally - improve cross team working and planning, and;

Other ideas to explore - travelling library – to find out about Parliament and give views on issues.

Successor committees might wish to consider: agreeing a strategic approach to engagement – aims, key outcomes and audiences, from the outset; early and direct engagement with stakeholders and communities; developing an ongoing dialogue on key issues such as climate change, and using approaches such as deliberative engagement, digital engagement. In order to hear from people with lived experience in a way that is supportive, meaningful and ethical, in Session 6 it is suggested that effective ways to support this are:

Working in partnership with organisations who have established trusted relationships and methods of working with the people the Committee seeks to hear from, and to co-develop approaches together. For example, with Third Sector Interfaces;

Allowing engagement staff, where appropriate and as agreed by Members, to work independently to co-produce sessions and deliver them with or without Member involvement. Staff can explore different and creative ways of doing that and report back to Committee;

Using a partnership approach brought new and different groups together to share experiences and approaches and to work together. There could be added benefit in developing as a facilitating and networking role;

Communicating and producing information in a number of different formats and media, making it clear and accessible. Before during and after engagement, and;

Integrating engagement planning and outcomes across all teams.

Communications

Agreeing strategic priorities for communications, engaging on issues of national and local interest and responding to issues that are high on the public agenda has proved successful this session. Successor committee(s) may wish to consider their audiences and how to ensure that its messaging is clear and accessible. Over the course of Session 5 the Committee sought to produce shorter, more focussed reports, in plain English which contained executive summaries or key messages to ensure accessibility to both the press and the public and made more use of letters. The Committee also used infographics and embedded clips can to help ‘bring these to life’. Some of the approaches successor committee(s) may wish to consider in promoting their work include:

Further expansion of social media opportunities and platforms, use of clips, blogs, videos;

Negotiating a media exclusive with the environment correspondent of a leading Sunday newspaper followed up by a wider news announcement;

Issuing press releases under embargo with the offer of pre-records or a press briefing in advance of publication to aid information gathering;

Setting up photo-calls to highlight an issue through personalities, something novel/creative;

Making more use of letters – clear, direct and concise letters to the Scottish Government can help promote transparency and maintaining a story in between evidence sessions;

Promoting evidence sessions in advance (sometimes with a convener quote or video clip) and where appropriate flagging to press key take-aways from a meeting;

Issuing pro-active and reactive media statements, releases and interviews, and;

Producing short, focused reports.

Future issues and priorities for consideration

Context for scrutiny in Session 6

The implications of EU exit in Scotland, which will include the formation of new institutions, policy frameworks, inter-governmental and intra-UK ways of working, are likely to feature strongly in scrutiny through Session 6. Supporting a green recovery and responding to the twin climate and ecological crises are heavily inter-related themes likely to dominate the next session of the Scottish Parliament in this portfolio area and more widely. A detailed analysis of future priorities and issues for consideration is included in Annexe 8. A summary of the future priorities and issues for consideration is set out below.

Building effective post-EU exit environmental governance and funding regimes

Successor committees may wish to consider early in the session how they will play an active role in scrutinising Scottish Ministers’ use of the keeping pace power and the extent to which Scotland seeks to align with EU standards, and how it will monitor the ongoing implications of EU exit for devolved competence on the environment, and well as on environmental outcomes. Opportunities for influence or further work to ensure effective scrutiny may include:

Scrutinising the monitoring framework for the Environment Strategy and consider the Scottish Government’s performance against the Strategy;

Engaging with the development of Common Frameworks at an early stage in their development, including consideration of whether they align with key Scottish environmental legislation and policy and continuing to develop interparliamentary approaches to scrutiny in this area;

Monitoring implications of the UK Internal Market Act for environmental standards in Scotland;

Consideration of the mechanisms by which the Scottish Parliament becomes appraised of developments in EU law;

Monitoring the implications of the EU-UK TCA for environmental standards in Scotland, including the representation of Scottish interests in the governance of the TCA;

Exploring the implications of future UK trade deals for Scotland’s environment;

Engaging with Environmental Standards Scotland as it develops its strategy, including how it will work with other UK governance bodies and engage with civil society, and considering what approach will be taken to consideration of any improvement notices;

Scrutinising forthcoming guidance on environmental principles;

Monitoring how shared powers in the UK legislation, such as the Environment Bill, are used and whether the Scottish Parliament is able to meaningfully scrutinise UK Statutory Instruments in devolved areas, and;

Scrutinising plans for EU replacement funding, in particular for rural support, and the extent to which they align with ambitions for net zero and nature recovery.

A green recovery amid twin climate and ecological crises

Successor committees may wish to prioritise the green recovery in their financial scrutiny, monitoring progress and impacts of Green New Deal commitments and opportunities to scale-up the flow of private finance into net zero goals and Scotland’s natural capital. Opportunities for influence and further work may include:

Scrutiny of Green New Deal commitments in budgets including the potential for frontloading of low carbon investment and conditionality of support;

Continuing to work with the Government - through the Joint Budget Review - on how climate change information is presented in the Scottish Budget and how budgets are aligned with Climate Change Plans;

Exploring innovative mechanisms for investment in low carbon and natural capital programmes including engaging with the newly established SNIB, and;

Building in consideration of the potential for environmental fiscal reform in relevant policy areas, such as the circular economy.

Infrastructure for net zero, nature and wellbeing

Successor committees may wish to engage with development of policy on infrastructure and placemaking to ensure it is aligned with net zero goals and the need for nature recovery. Opportunities for influence and further work may include:

Considering the Scottish Government’s infrastructure investment priorities and infrastructure’s role in reaching the net zero target in 2045 and reversing biodiversity decline;

Considering Scottish Water’s investment priorities in the context of the net zero target and affordability for customers;

Scrutinising NPF4, considering alignment with the Climate Change Plan, Land Use Strategy and other key strategies;

Exploring how provision of greenspace can be integrated into planning and infrastructure provision for wellbeing and biodiversity, including opportunities for vacant and derelict sites to be used for green infrastructure, and;

Exploring the role of mechanisms such as City Deals and Sustainable Growth Agreements in delivering low carbon and natural infrastructure.

Mainstreaming nature recovery and net zero into land management

Successor committees may wish to work to identify the key interventions needed to mainstream nature recovery in Scotland, including opportunities to address climate change and biodiversity loss as twin crises. Key opportunities for further work and influence may include:

Considering of how any global biodiversity agreement should be translated into biodiversity targets and action in Scotland;

Scrutinising the third Land Use Strategy and consider its alignment with other key strategies such as the updated Climate Change Plan, future rural policies and NPF4;

Monitoring the implementation of the Land Use Strategy through the Scottish Government’s annual reports to Parliament and assess the extent to which more integrated land use is visible in practice;

Considering how to engage across Parliament on nature recovery e.g. integrating issues in scrutiny of planning, infrastructure and financing policies;

Engaging with the Government, Scottish Land Commission and other stakeholders on the development of Regional Land Use Partnerships;

Monitoring implementation of recommendations of the Werritty review, in particular exploring the most appropriate model for grouse moor licensing;

Monitoring implementation of the recommendations of the Deer Working Group report;

Monitoring achievement of targets for nature-based solutions, and;

Scrutinising the coherence of Government policy on peatlands across commitments on peatland restoration and peatland protection.

Linking land reform and the green recovery

Successor committees may wish to further explore the role of land reform in supporting a green recovery, including its role in supporting community action and social resilience in relation to climate change, the wellbeing economy and nature recovery. Opportunities for future work and influence might include:

Engaging with the Government, Scottish Land Commission and other stakeholders on the development of Regional Land Use Partnerships;

Exploring the recommendations of the Scottish Land Commission in relation to concentration of land ownership, and;

Continuing to work with the Scottish Land Commission including scrutiny of its research, proposals and strategic plan.

Restoring marine and freshwater biodiversity - a blue recovery

Successor committees may wish to ensure marine issues are integrated across relevant areas of scrutiny to ensure steps are taken to enable nature recovery in the marine environment e.g. integrating marine considerations into any future work on nature-based solutions, replacement EU funding and planning and infrastructure. Opportunities for future work and influence could include:

Scrutinising the Blue Economy Action Plan and 2021 review of the National Marine Plan and Marine Protected Areas from a marine environment perspective, taking account of previous Committee work on regional marine planning, aquaculture, blue carbon, and marine planning and enhancement;

Exploring how the Fisheries Management Strategy 2020-2030 will support nature recovery and net-zero;

Continuing to explore the opportunity for strategic mechanisms to deliver enhancement of Scotland’s marine environment;

Exploring implications of the post-EU exit governance framework for marine biodiversity including funding and governance arrangements;

Scrutinising the outcome of annual post-Brexit fisheries negotiations between the UK, EU and other coastal states and its implications for sustainable fisheries in Scottish waters;

Scrutinising the forthcoming Joint Fisheries Statement published by the four UK governments, and the extent to which it demonstrates how fisheries objectives will be met to ensure sustainable management of the marine environment; and keeping a watching brief on the Secretary of State Fisheries Statement with regard to potential implications for sustainable management of Scottish fisheries;

Scrutinising ongoing work to improve the environmental performance of Scottish salmon farming, e.g. as part of scrutiny of the NPF4, and reviewing the Scottish Government’s response on interactions between wild and farmed salmon;

Scrutinising forthcoming post-2020 biodiversity policy in relation to the health of the freshwater and marine environments, and;

Scrutinising annual changes to river gradings to monitor the health of the freshwater environment.

Developing Scotland’s Circular Economy and achieving sustainable consumption

Successor committees may wish to explore the required actions to transition to a circular economy in Scotland for net zero and nature recovery as well as reducing Scotland’s carbon footprint. Opportunities for future work and influence may include:

Exploring Scotland’s global environmental impact related to consumption including the need for any further governance around consumption emissions;

Scrutinising the implementation of DRS in Scotland;

Reviewing how the UK legislation on producer responsibility, DRS and the Internal Market Act interact and impact plans and delivery in Scotland;

Monitoring to what extent the Scottish Government is keeping pace with EU developments under its Circular Economy Programme;

Considering how the Scottish Parliament engages with the development of and scrutinises any secondary legislation introduced by the UK Government using powers Environment Bill e.g. on producer responsibility;

Scrutinising routemaps for meeting waste and recycling targets and circular economy ambitions promised in the draft Climate Change Plan update;

Exploring with public bodies how they are using public procurement to further net zero and circular economy ambitions, and;

Exploring use of environmental fiscal reform to support the green recovery and the transition to a circular economy.

Improving Scotland’s air quality

Successor committees may wish to work to ensure that opportunities to improve air quality, including any lessons learned during Covid-19 restrictions, are integrated into green recovery plans and related areas such as infrastructure planning and investment in green infrastructure. Opportunities for future work and influence may include:

Monitoring the next Scottish Government’s response to the CAFS review and scrutinise the new air quality strategy in 2021;

Scrutinising the rate of progress on LEZs and their ambition, and;

Engaging with local authorities as part of any work on air quality.

Protecting animal welfare

Successor committees may wish to engage with the new Scottish Animal Welfare Commission on its workplan and priorities including any work on animal sentience, to inform its approach to animal welfare during the next Parliamentary sessions. Opportunities for future work and influence may include:

Exploring the relevance of animal welfare standards to Scotland’s resilience to zoonotic diseases;

Engaging with any future legislation on fox control;

Engaging with NatureScot on relevant workstreams on wildlife management relevant to animal welfare such as its forthcoming review of snaring, and;

Considering the petition on greyhound racing in Scotland.

Reducing Scotland’s emissions

Successor committees may wish to scrutinise the Scottish Government response to the climate emergency and commitment to put climate change at the heart of government and policy making. Opportunities for future work and influence include: