Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

Legislative Consent Memorandum on the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill

Introduction

The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill (“the Bill”) was published on 13 July 2017. It received its First Reading in the House of Commons on that day and its Second Reading on 7th and 11th September 2017. This is a bill of immense significance and subject to considerable debate.

As the Committee makes this report the Bill has progressed to the Committee Stage. This report refers to the Bill at introduction in the House of Commons. The Committee fully expects that the Bill will be subject to amendments. At the same time, this Parliament will continue to reflect on how it might build on its scrutiny processes as further information emerges about the timing and scale of the subordinate legislation project under the Bill. Accordingly, the Committee would expect to return to its consideration of the Bill in the near future.

The Committee’s report is on the Legislative Consent Memorandum (LCM) for the Bill rather than on the Bill itself. The Finance and Constitution Committee is the lead committee for consideration of the LCM and therefore the Committee directs this report to that Committee.

The Bill

The Explanatory Notes to the Bill state that the Bill performs four main functions. It:

repeals the European Communities Act 1972;

converts EU law as it stands at the moment of exit into domestic law before the UK leaves the EU;

creates powers to make secondary legislation, including temporary powers to enable corrections to be made to the laws that would no longer operate appropriately once the UK has left the EU and to implement a withdrawal agreement; and

maintains the current scope of devolved decision-making powers in areas currently governed by EU law.

The Legislative Consent Memorandum

The Committee is considering the LCM for this Bill. That LCM was lodged by the Scottish Government on 12 September 2017.

LCMs are lodged in relation to bills under consideration in the UK Parliament which contain what are known as “relevant provisions”. These are provisions which:

change the law for a purpose within the Scottish Parliament’s legislative competence (its powers to make laws in areas of policy devolved to the Scottish Parliament under the Scotland Act 1998); or

alter the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament or the executive competence of Scottish Ministers (their powers to govern).

The Bill is a relevant bill within Rule 9B.1.1 of the Scottish Parliament’s Standing Orders as it makes provision applying to Scotland for purposes within the legislative competence of the Parliament and alters that legislative competence and the executive competence of the Scottish Ministers.

The Parliamentary Bureau referred the memorandum to the Finance and Constitution Committee as lead committee for consideration of the Bill.

As the Bill contains provisions that confer new powers to make subordinate legislation, the remit of this Committee is also engaged.

This Committee reports its conclusions on the relevant provisions in the Bill to the Finance and Constitution Committee who will in turn make a report to the Parliament.

In most circumstances, following the lead committee’s report on the memorandum, the Scottish Government would lodge a Legislative Consent Motion to be taken in the Parliament seeking the Parliament’s consent to the UK Parliament legislating on devolved matters. The Scottish Government has indicated that it does not intend to lodge such a motion because it cannot give its consent to the Bill as it stands.

The Scottish Government has intimated that, depending on whether and how the Bill is amended and the outcome of other negotiations with the UK Government, it may lodge a supplementary LCM on this Bill in due course. That supplementary LCM may potentially include a draft legislative consent motion.

It is extremely unlikely that this will be the Committee’s only report in relation to the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill. This is a report on the Bill as introduced into the House of Commons on 13 July 2017. However, the Bill is just beginning its Committee Stage in the House of Commons and large numbers of amendments have been lodged to the Bill. It seems highly likely that the Bill will be subject to significant amendment in the course of its progress through the UK Parliament.

The Committee will also want to reflect further in future reports on more technical drafting matters in relation to the Bill, which are currently being explored with the UK Government.

Committee consideration of the Bill

Insofar as the powers conferred on the Scottish Ministers are concerned, the Committee has taken the same approach to consideration of this Bill as it would normally take on a bill. The Committee recognises the importance and unusual nature of the Bill. However, it has focussed on the same four questions it asks on all bills.

Firstly, the Committee has considered whether it is appropriate to delegate the powers the Bill proposes to confer on the Scottish Ministers. The Committee has considered whether the matters proposed to be delegated are appropriate for delegation or whether they would more appropriately be set out on the face of the Bill. Is the need for such wide powers warranted and has sufficient justification been provided? Has the right balance been struck between what is on the face of the Bill and what has been left to secondary legislation?

Secondly, the Committee has considered the breadth of the powers. It has sought to assess whether they are appropriately drawn and whether they could be expressed in a way that makes it clearer how the powers will be exercised.

Thirdly, the Committee has considered the correlation between the policy intention as expressed in the Delegated Powers Memorandum and what the Bill enables the Scottish Ministers to do in exercise of the powers.

And fourthly, the Committee has considered whether the powers are subject to an appropriate level of parliamentary scrutiny.

However there are further issues which arise due to the unique nature of this Bill, concerning the powers of UK Ministers, which the Committee has also focussed on.

The Bill confers powers on UK Ministers, concurrent with those of the Scottish Ministers, to make regulations relating to matters within devolved competence. The Committee has accordingly considered questions about scrutiny of the choice which will allow either UK or Scottish Ministers to bring forward legislation in devolved areas.

The Committee has also considered the question of scrutiny by the Scottish Parliament, in those cases where the choice is exercised in favour of bringing forward subordinate legislation in the UK Parliament rather than the Scottish Parliament.

Finally, the Committee has considered other unique features of the Bill, such as the ability of UK Ministers to modify the constitutional settlement.

To inform its consideration of the Bill, the Committee issued a call for evidence to individuals and organisations and also promoted the call for evidence on its website and via Twitter.

The submissions received are listed at Annex A.

The Committee also held oral evidence sessions on 26 September, 24 October and 8 November 2017. Evidence was taken from bodies representing the legal sector, academics, environmental bodies, the Scottish Government and the UK Government. This information can also be found in Annex A.

The Committee thanks those who informed its consideration of the LCM.

Parliamentary processes and procedures

This Bill has raised the public profile of the scrutiny of secondary legislation. There are frequent references in the media to secondary legislation and the scrutiny arrangements attached to it. Nevertheless this terminology is still unfamiliar to many. Yet it is crucial to understanding this report and the basis for the Committee’s recommendations.

The Committee has confidence in the robustness and thoroughness of the Scottish Parliament’s existing processes for the scrutiny of secondary legislation.

The Committee recognises that concerns have been raised about the adequacy of parliamentary processes to deal with the expected volume of secondary legislation. The Committee believes that for the most part the processes in the Scottish Parliament are sufficiently flexible to enable the Parliament to meet the demands of additional and complex secondary legislation under this Bill.

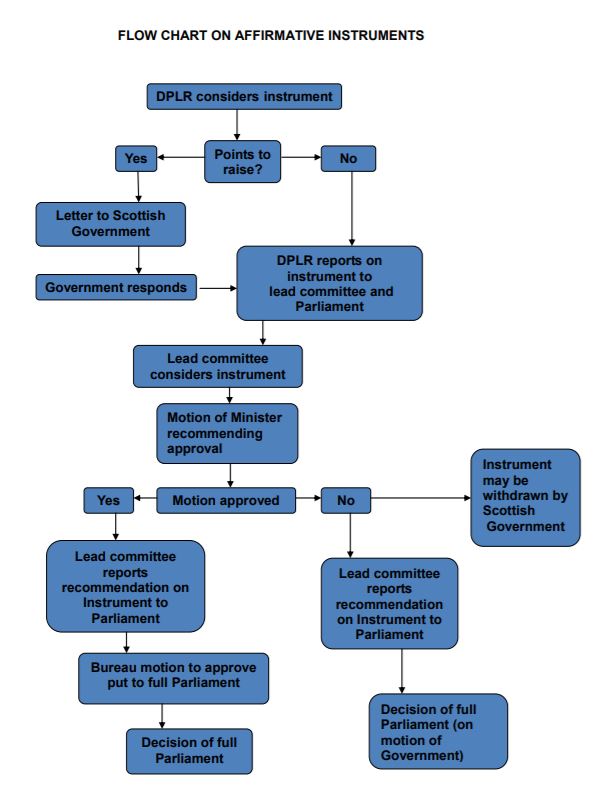

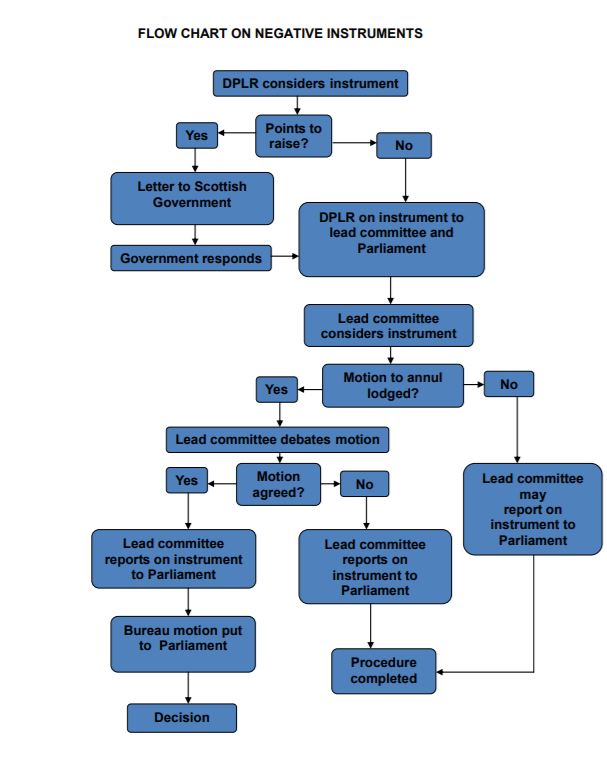

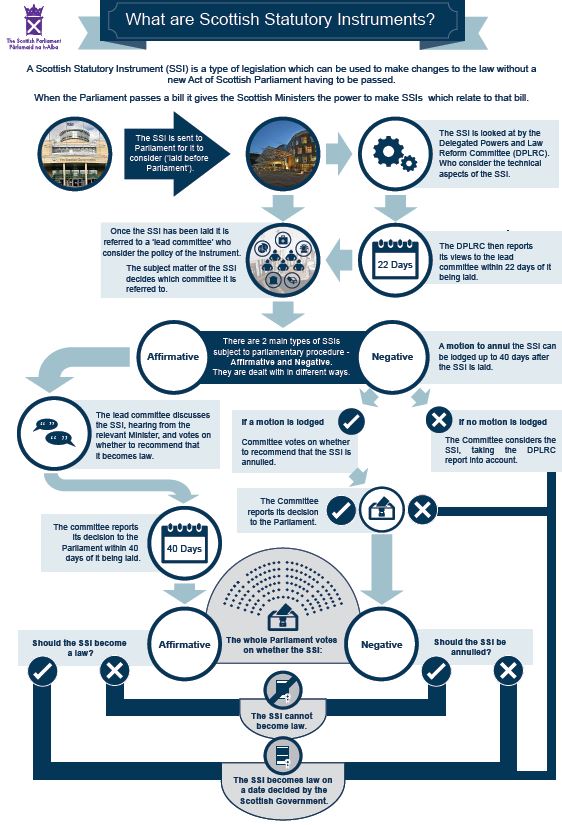

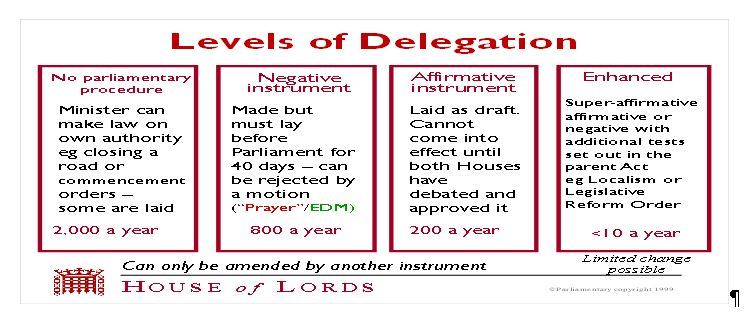

At Annex B there is an explanation of the Scottish Parliament’s processes and procedures and how these differ from the processes and procedures in the UK Parliament.

Broad Powers

An unprecedented volume of changes to our laws will be required to be made to provide for a legally competent withdrawal from the EU. Moreover these changes will need to be made in a relatively short period. In order to provide the flexibility needed to support the Brexit negotiations, the Bill proposes delegating wide legislative powers to UK Ministers and the Ministers of devolved administrations. This means that legislation of a type which might in normal circumstances be brought to the UK Parliament or to the devolved legislatures through primary legislation will instead be made by secondary legislation. This enables Ministers to act quickly and flexibly, but it provides fewer opportunities for detailed parliamentary scrutiny.

The most critical question this Committee must answer on this Bill is whether it is appropriate for the Parliament to delegate power to Ministers. The primary purpose of a parliament is to legislate and therefore if it is to delegate that primary purpose it must give thorough and careful consideration to that decision. It is undeniable that there are circumstances where it is appropriate to hand that power over. For example, highly detailed process-related matters would, for the most part, normally be expected to be dealt with in secondary legislation. It would be an inappropriate use of parliamentary time to include such matters in primary legislation.

However, there are other times where it is less clear that granting power to Ministers to make secondary legislation is appropriate. This Committee and its predecessor committees over more than one session of the Parliament have consistently raised concerns about the use of so-called framework legislation, where the powers are broad, ill-defined and appear to be a substitute for considered policy development.

This Bill confers extremely broad powers on Ministers, the limits of which are unclear. In any normal circumstances the conferral of such wide powers would be unacceptable. It was suggested to the Committee, however, that these were unique circumstances and therefore wide powers were unavoidable.

Professor Alan Page expressed this sentiment:

“I am conscious that this discussion is taking place while the legislation is being enacted against the background of a challenge on a scale that is unprecedented outside wartime. It is important not to lose sight of just how big the task is...It is understandable, therefore, that broad powers should be sought to address the consequences, not knowing what all those consequences are at the moment at which the powers are being sought.”i

This was echoed by Professor Stephen Tierney:

“My view of the bill might seem a little paradoxical. When I look at the powers, I can see that they are very, very broad and raise real constitutional concerns. However, when I ask myself how one would go about it in a different way, I find it difficult to come up with a concrete alternative that would, constitutionally, be better and that would make the process manageable, because we are talking about a very short period of time and a massive body of law that must be dealt with.”ii

However, Dr Tobias Lock was not so persuaded on the need for broad powers:

“It is questionable whether these powers are entirely appropriate. There is admittedly a need for powers to correct retained EU law where it would otherwise not work. For instance, references to EU law in these instruments will need to be corrected. Equally, EU law may provide for a reporting duty to the European Commission, which after Brexit becomes redundant and must either be replaced or removed. However, the breadth of these powers – based on a definition of ‘retained EU law’ that goes beyond what is technically necessary in order to salvage existing provisions and keep the legal system functioning – would seem to be both unprecedented and ill-defined.”iii

One of the principal concerns raised with the Committee related to the level of discretion available to Ministers in the exercise of these powers. This concern was formed on the wording of Clause 7, but applies equally to the equivalent power of the Scottish Ministers in Part 1 of Schedule 2. Witnesses suggested that the discretion in Clause 7 will enable Ministers to use the powers to make policy changes rather than the mechanistic changes the UK Government has explained the Bill is designed to make.

Clause 7 (and the equivalent power in Part 1 of Schedule 2) gives Ministers powers to make regulations which they consider appropriate to “prevent, remedy or mitigate” any failures of retained EU law to operate effectively or any other deficiency in retained EU law.

The Bill is described by the UK Government as a straightforward exercise in getting the statute book into shape as a consequence of Brexit—in other words, as a technical, tidying-up exercise. The Delegated Powers Memorandum refers to Ministers having the power by regulations to make “necessary” corrections to the statute book.

Robin Walker MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, explained to the Committee the intention behind the powers:

“The whole approach to the bill is about continuity and certainty as we go through the process; it is not about making policy change.”iv

However, it was suggested by witnesses that the word “appropriate” provided Ministers with too much discretion in the exercise of their powers and that might enable Ministers to make policy changes, contrary to what the Delegated Powers Memorandum suggests.

Professor Page suggested that this discretion might allow for substantive policy changes to be made under the guise of technical changes.

The Law Society of Scotland also expressed concern about the level of discretion available to Ministers under the Bill. It suggested that replacing “appropriate” with “necessary” would provide a greater sense of objectivity and would require a more evidenced based approach, potentially avoiding policy driven changes.

Furthermore, Scottish Environment Link suggested that the powers in the Bill could be constrained by a requirement that they must only be used to ensure that retained EU law operates with equivalent scope, purpose, and effect to existing EU law, or to implement any rights or obligations arising from negotiations with the EU on withdrawal.

In relation to Clause 7, the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee in the House of Lords concluded that the concept of “appropriateness” provides scope for UK Ministers “…to make regulations arising from EU withdrawal with an extensive policy content across the whole of retained EU law.”v

That Committee recommended that the appropriateness test should be “circumscribed in favour of a test based on necessity” as the Bill currently allows for substantial policy changes that ought to be made only in primary legislation.v

The House of Lords Constitution Committee also concluded that the powers are insufficiently constrained in this regard and leave open the possibility that the powers could be used to make significant policy changes.

This lack of constraint is compounded by the vagueness and ambiguity within the language used in describing the powers available to Ministers. In particular, the Committee is concerned about the meaning of “deficiencies”. A broad interpretation of that term could again provide Ministers with the power to make significant policy changes without the need for primary legislation.

RSPB Scotland also highlighted the uncertainty about what constituted a technical change and consequently the reach of the powers under the Bill. In practical terms, RSPB Scotland and Scottish Environment Link expressed concern that the powers could be used to remove or abolish governance or oversight arrangements currently performed by EU bodies rather than simply replicating them.vii

The Committee explored these concerns with Michael Russell MSP, the Minister for UK Negotiations on Scotland’s Place in Europe. In particular the Committee asked for his perspective on changing the test from one of “appropriateness” to one of “necessity”. He reflected that the powers should not be capable of being exercised in a way that allows for significant policy changes and intimated that he was not unsympathetic to the idea of narrowing the power.

The Committee explored with UK Ministers why they had adopted this “appropriateness” test. Robin Walker MP explained to the Committee the need for an “appropriateness test”:

“…where for example, two different solutions may be possible, that does not mean that either one of them is necessary. There is therefore a need for a power to introduce the delegated legislation if it is appropriate, rather than just where it is necessary, because the constraint of being necessary would lead to some circumstances where we might not be able to take steps that you or I would see as necessary, because there was a choice of two different ways of addressing the issue.”viii

Recommendations

The Committee reluctantly accepts that the unprecedented task of modifying domestic legislation to preserve the statute book on leaving the European Union, and the short timeframe in which it is to be done, necessitates broad powers. In any other circumstances the conferral of such wide powers would be inconceivable, but the Committee accepts that in these circumstances the taking of wide powers is unavoidable.

However, the Committee considers that the powers should only be available where Ministers can show that it is necessary to make a change to the statute book, even if they cannot show that the particular alternative chosen is itself necessary.

The Committee notes that Ministers confirmed that the powers are not to be used to make policy changes. The Committee welcomes this. The powers should not be used to make policy changes.

The Committee acknowledges that Ministers need to be able to make choices between alternative options where a change is required in order to remedy a deficiency in EU law. It is the Parliament’s role to scrutinise that choice.

However, the Committee recommends that Ministers consider further the suggestion made by other committees that the powers should be based on a necessity test rather than an appropriateness test. It anticipates that it should be possible to find some wording which would restrict Ministers to using the power only where necessary, while still enabling a choice to be made between competing solutions depending on which is most appropriate.

Protection of Constitutional Statutes

The Committee examined ways in which the powers of the UK Ministers and Scottish Ministers could be constrained.

Clause 7(6)(f) provides that the Northern Ireland Act 1998 is effectively protected from repeal or amendment by subordinate legislation made under the powers in this Bill. Such protection is not afforded to the Wales Acts or the Scotland Acts.

The Delegated Powers Memorandum explains why the Northern Ireland Act 1998 has been given specific protection:

“The restriction on amending parts of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 is because that Act is the main statutory manifestation of the Belfast Agreement and it would not, therefore, generally be appropriate for a power with this breadth of scope to be capable of amending that Act.”

The Committee explored with witnesses whether this protection should be extended to the Scotland Act 1998.

Michael Russell MSP argued that the Scotland Act 1998 should be protected in the same way as the Northern Ireland Act 1998:

“There should be a further restriction of the powers …because the ability to amend Northern Ireland devolution statutes is explicitly referred to in the bill, so that it is not possible to amend them. I can see why it is the case, but I do not think that it is right that there will be no power to amend Northern Ireland devolution statutes while power to amend Welsh and Scottish statutes would remain. We have made that concern absolutely clear.”i

The Committee notes the suggestion by Professor Tarunabh Khaitan, from the University of Oxford, that a limit on enacting changes of constitutional significance could be appropriate in the context of the powers in this Bill.

He argues that a “constitutional protection clause” would have the advantage of limiting the power without restricting the overall flexibility of the power, and might lessen the chances of the courts imposing a more maximalist restriction on using the power to enact measures with constitutional implications.ii

Robin Walker MP explained to the Committee that he appreciated the special standing of the devolution Acts and highlighted that the Bill corrects as many deficiencies as possible in those Acts on the face of the Bill in Part 2 of Schedule 3. However, he suggested a power to correct deficiencies arising in these Acts is necessary to avoid gaps in the statute book.

Recommendations

The Committee supports the concept of a constitutional protection clause. The Committee understands the justification for providing specific protection to the Northern Ireland Act, however, the Committee equally believes that protection should also be afforded to other constitutional statutes including the Scotland Act 1998.

At the same time, the Committee recognises that the Scotland Act 1998 is already amendable by way of secondary legislation. Significant amendments made to that Act by secondary legislation, such as changes to competence or to Ministers’ functions are, however, subject to scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament.

It is not appropriate that matters of such constitutional import should be amendable by secondary legislation that is subject to scrutiny in the UK Parliament alone. Where it is considered necessary to amend constitutional statutes such as the Scotland Acts this should be done in a way which is subject to thorough and meaningful scrutiny in this Parliament.

Powers not available to the Scottish Ministers

There are powers in the Bill that are available to UK Ministers, but not to the Scottish Ministers. This section of the report considers these powers and suggests whether or not they should also be conferred on the Scottish Ministers.

Clause 17: Powers to make consequential and transitional provision

Clause 17 contains a power to make such consequential provision as is considered appropriate in consequence of the Bill. It also contains power to make transitional, transitory or saving provision in connection with the Bill coming into force.

These powers are conferred on UK Ministers, but not the Scottish Ministers.

The Delegated Powers Memorandum explains the reason for taking the power to make consequential provision:

“This Bill creates a substantial change to the legal framework of the UK. The Government is unable to identify, at this early stage, all the possible consequential provisions required. In the circumstances, it would be prudent for the Bill to contain a power to deal with consequential provisions by secondary legislation. The power is limited to making amendments consequential to the contents of the Bill itself, and not to consequences of withdrawal from the EU which are addressed by powers already discussed.”

Kenneth Campbell QC, giving evidence on behalf of the Faculty of Advocates, suggested that he could see value in the Scottish Ministers having this power:

“One can clearly envisage that, if the Scottish Ministers exercised the powers that are conferred elsewhere in the bill, consequential tidying-up things might well need to be done.”i

The Committee explored with UK Ministers why the power had not been afforded to the Scottish Ministers. Chris Skidmore MP, Minister for the Constitution, suggested that it was not normal practice to confer such a power on Ministers in devolved administrations. He did, however, highlight that the devolved administrations have power to make consequential provision when they are exercising their powers under schedule 2. Furthermore, he committed to listening to any concerns on this issue.ii

Recommendations

The Committee recognises that ancillary powers of this nature have the potential to have far-reaching effects. The need for their inclusion in a bill has to be made out on a case by case basis.

At the same time, the Committee can see the potential for gaps to arise as a consequence of this Bill in areas of legislation which solely affect the Scottish Parliament or the powers of the Scottish Ministers. An example might be in the statutory codes of interpretation which apply to Acts of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish statutory instruments. These gaps may not become clear until after the Bill is in force.

The Committee recommends that further thought be given to the question of whether powers equivalent to those in clause 17 be conferred on the Scottish Ministers, to enable them to plug any gaps arising as a consequence of the Bill or in relation to transition to the new regime, within Ministers’ extended legislative competence as conferred by this Bill. Such an approach would enable the exercise of these ancillary powers to be scrutinised in the Scottish Parliament.

Restrictions on the Scottish Ministers’ powers

The Bill introduces the concept of “retained EU law” to describe the body of EU law which will continue to have effect on and after exit day. Retained EU law comprises the following areas of law:

existing domestic law relating to the EU or EU obligations (defined in the Bill as “EU-derived domestic legislation”). This will include primary and secondary legislation passed by the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament (clause 2);

EU law that has direct effect (i.e. did not require the passing of primary or secondary legislation) and applies to the UK immediately before exit day (but sits outside domestic law) will become part of UK domestic law on exit day (defined in the Bill as “direct EU legislation”) (clause 3); and

directly effective rights under the EU Treaties (clause 4). This will include rights of movement and residence.

The powers conferred on the Scottish Ministers are subject to some significant restrictions which do not apply to the corresponding UK Ministers’ powers. These include the restriction in Schedule 2, paragraph 3(1) that the Scottish Ministers only have power to adjust existing EU-derived domestic law (not retained direct EU legislation or anything which is retained EU law by virtue of clause 4, such as directly effective Treaty rights).

The Committee explored with witnesses whether it was appropriate for the Scottish Ministers to be precluded from having the power to amend retained direct EU legislation and directly effective Treaty rights. The Committee received conflicting evidence on this issue.

Professor Page suggested that there is good reason for this restriction:

“It is probably worth keeping it in mind during our discussion that one of the principles of the legislation is that it is intended to provide continuity of laws. If you had four Governments—we have four Governments in the UK, not just one— changing the law, it could be extraordinarily difficult for anyone to work out what the law was. I would hesitate to object to that on the basis that they can do it and we cannot, because of the potential consequence of everyone being able to modify retained EU law.”i

Michael Russell MSP, however, argued that the Scottish Ministers should not have these restrictions imposed upon them. The Minister argued that the concept of retained EU law is not one that will stand still and therefore the argument that there would be an ongoing consistent body of retained EU law was not one he found persuasive. He also highlighted that devolution is predicated on subsidiarity and accordingly there should be scope for variation with decisions made at the appropriate level. He recognised, however, that there would be times where a common framework would be appropriate.ii

The Committee sought to understand from the UK Ministers why these restrictions on the Scottish Ministers powers had been imposed.

Robin Walker MP argued that the approach respects the frameworks of devolution and respects the ability of the devolved legislatures to have their say on all the issues, while ensuring that there is a process for dealing with the frameworks that are required to continue functioning.iii

Recommendations

The Committee notes that this is an immensely important issue and one that is at the heart of shaping how common frameworks will work. This is a policy issue.

The Committee appreciates that the Finance and Constitution Committee is considering the issues around common frameworks and accordingly draws that Committee’s attention to the evidence this Committee has taken on the issue.

Fees and Charges

Paragraph 1 of Schedule 4 of the Bill confers a wide power on UK Ministers and devolved authorities to create fees and charges in connection with functions which public bodies in the UK take on exit day, and also to modify those fees or charges.

The Delegated Powers Memorandum explains the purpose of the power:

“It enables UK ministers and devolved authorities to create fees and charges in connection with functions that public bodies in the UK take on exit, where appropriate, and also modify them in future. Whilst this power will not be used in connection with every function being repatriated, it ensures ministers have the flexibility to ensure the burden of specific industry-related costs does not fall onto the general taxpayer (including in cases where EU institutions currently charge).”

As explained in the Delegated Powers Memorandum, the power goes beyond enabling public authorities to recover the costs of their functions. It is wide enough to enable taxation measures to be imposed, for example to cross-subsidise, or to cover the wider functions and running costs of a public body, or to lower regulatory costs for certain groups or sectors.

The Committee explored with UK Ministers why it is appropriate for taxation measures to be included in subordinate legislation. Robin Walker MP explained the need for the powers:

“As part of the preservation of EU law, directly affected provision on how an EU institution or agency can levy fees or charges on individuals will be converted into domestic law. The bill enables us to preserve UK domestic fees and charges that are connected with EU law under section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972 and section 56 of the Finance Act 1973: we will repeal the former, and the latter will no longer be exercisable in relation to EU obligations on exit, which means that a replacement power to make and update fees and charges is needed.

This is a very technical issue. I assure you that there is no intention to introduce new taxes or use broad powers under the provisions; it is very much about keeping things working in the way in which they have done previously.”i

The Committee also explored why it is appropriate for UK Ministers or devolved administrations to sub-delegate the power to create fees or charges to a public body, and for that body to impose those fees or charges administratively, rather than by way of statutory instrument. Again Robin Walker MP contended that this was about replicating the effect of arrangements that exist in the European Union.

The Committee is not persuaded by the Minister’s response regarding ensuring equivalence with existing powers to impose fees or charges in respect of EU functions. It notes that powers under the European Communities Act 1972 may not be used to impose or increase taxation.

The Bill provides that where regulations under this power impose a new fee or charge, the affirmative procedure will apply to scrutiny of those regulations. But where subsequent regulations modify the fees or charges, the negative procedure will apply. In theory then, successive governments may impose fee increases by regulations subject only to scrutiny under the negative procedure. The Committee asked UK Ministers why this was appropriate.

Again the UK Ministers contended that the approach was to replicate current arrangements:

“I believe that the scrutiny procedures that you have referred to also reflect the current scrutiny procedures for fees and charges. The creation of a new fee will require the affirmative procedure, but its maintenance—updating it for inflation, for example, and so on—will require only the negative procedure.”ii

Recommendations

The Committee expresses its concern about the ability of Ministers to impose taxation measures in regulations made under Schedule 4.

It also agrees with the conclusions of the House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee regarding sub-delegation of this power. Ministers should not be able to sub-delegate the power to create fees or charges to a public body, enabling that body to impose those fees or charges administratively rather than by way of statutory instrument. It appears to the Committee that sub-delegating the power to charge fees in this way will not create the transparency and certainty which business is seeking following EU withdrawal.

The Committee also echoes the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee’s recommendation that the affirmative procedure should apply to all regulations under Schedule 4 which introduce or increase fees. This Committee has consistently in its various reports on delegated powers made the point that applying the affirmative procedure to the first use of a power, and the negative procedure to subsequent uses, is unacceptable in principle. In this case such an approach would allow an initially very small fee to be set by affirmative regulations, with a subsequent significant increase imposed by negative regulations.

Legislative routes

Under the Bill there are three routes to address EU law deficiencies in domestic legislation applying to Scotland and having a devolved purpose.i

Regulations made by UK Ministers acting alone and laid in the UK Parliament;

Regulations made by the Scottish Ministers acting alone and laid in the Scottish Parliament;

Regulations made by UK Ministers and Scottish Ministers acting jointly and laid in both Parliaments.

The Bill does not regulate how decisions are to be made as to which Ministers should exercise concurrent powers.

The Committee explored each of these routes, the issues arising in relation to the different routes and what factors would precipitate the choice of a particular procedure.

However, before looking at these individual routes it is worth reflecting on the emphasis placed by Professor Tierney and Professor Page on the need for co-ordination and co-operation between the different governments to progress the legislation and decide on the most appropriate route.

Professor Page proposed a particular model of co-operation:

“I would like to see a system whereby there was a high-level committee that was responsible for the co-ordination of control and on which the devolved Administrations would be represented, and which would have oversight of departments’ legislative plans for what exactly would be done in the exercise of the powers. It would have oversight of the division of labour between the UK ministers and the Scottish ministers—what would be done on a UK-wide basis and what would be done by Scottish ministers, Welsh ministers and, assuming that the Northern Ireland Assembly is up and running again, their Northern Ireland equivalents—and it would ensure that the kinds of safeguards that we have been talking about in terms of the exercise of powers going no further than is necessary and being appropriate were observed.”ii

Recommendations

Where there is scope for secondary legislation to be made following different routes there must be clarity on which route is being pursued and why. The Committee believes that co-operation and co-ordination between governments is essential to the effective delivery of secondary legislation under the Bill. Co-ordination and co-operation between governments should, however, be in addition to and not a substitute for effective scrutiny of secondary legislation by the UK Parliament and devolved legislatures. It is for the legislatures to scrutinise that co-ordination and co-operation, and the decisions which flow from it.

Essential to that effective scrutiny is co-operation and co-ordination between legislatures.

Regulations made by UK Ministers acting alone and laid in the UK Parliament

The powers to deal with deficiencies arising from withdrawal in connection with devolved matters are wide and will allow UK Ministers to make regulations which apply to Scotland and which cover both reserved and devolved matters.

In practice, it is often currently the case under the 1972 Act that the UK implements EU obligations for Scotland and Wales in devolved areas. It will often make sense for a uniform approach to, for example, administration of certain EU schemes to apply throughout the UK, rather than bespoke provision being made by each devolved administration. This represents a pragmatic approach to implementation.

Mindful of the experience of the implementation of EU obligations, Professor Page suggested that this route would most likely be pursued frequently.i

Two specific issues arose in the Committee’s exploration of this route:

what the process will be for consenting to UK Ministers legislating in devolved areas; and

how the Scottish Parliament will scrutinise legislation in devolved areas, and in areas with a significant impact on Scottish interests, laid in the UK Parliament.

The Delegated Powers Memorandum indicates that, in the context of Clause 7, UK Ministers would “not normally” use the power to amend domestic legislation in areas of devolved competence without the agreement of the relevant devolved authority.

There is, however, no requirement on the face of the Bill for UK Ministers to obtain the agreement of the relevant devolved authority.

Professor Page argued that this route should only be pursued with the formal consent of the Scottish Ministers.

Michael Russell MSP also stressed the importance of having consent and highlighted the amendments proposed by the Scottish and Welsh Governments to include provision for a requirement for consent on the face of the Bill.

The Committee agrees that UK Ministers should only be able to legislate in devolved areas with the consent of the devolved administration.

Such a consent process does not, however, provide an opportunity for the Scottish Parliament to engage in the decision as to whether or not the Scottish Ministers should be offering their consent.

The Minister, however, suggested to the Committee that a process of notification equivalent to that under section 57(1) of the Scotland Act 1998 (which allows EU obligations to be implemented in areas within devolved competence by UK Ministers alone) would allow for the Parliament to hold the Scottish Ministers to account.ii

Luke McBratney, giving evidence on behalf of the Scottish Government, expanded on the section 57 process and how it applies to this Bill:

“The minister mentioned section 57 of the Scotland Act 1998, which is an existing example of the UK Government being able to implement EU obligations in devolved areas. That is done only at an administrative level, after bilateral consultation and with the formal agreement of the Scottish ministers. Scottish Government guidance on the use of that section requires that, when giving consent to the implementation of an obligation through section 57, the relevant portfolio minister should write to the convener of the Scottish Parliament committee that deals with the subject matter and to the convener of the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee.

That is the mechanism by which ministers are held accountable for their decisions to agree to the use of section 57. I expect that that is the sort of mechanism that is being discussed between Government and parliamentary officials to cover the similar issue that is raised by the proposal in the Scottish and Welsh Governments’ amendments to the bill that would require devolved ministers’ consent before the UK Government can make regulations in devolved areas.”iii

Professor Page suggested that the section 57 process had not always provided an effective means of holding the Scottish Ministers to account:

“…the Scottish ministers have not necessarily been accountable for the transposition of EU legislation. In other words, I assume that they have, in some cases, agreed to the transposition of EU directives on a UK-wide basis but kept completely quiet and not said a word about it to the Parliament.”iv

Recommendations

The Committee is of the view that the section 57 process is insufficient for these purposes.

While the Committee believes that the Bill would be strengthened by requiring the consent of devolved administrations before UK Ministers can legislate in devolved areas, the Committee believes that there needs to be a process for the Scottish Parliament to scrutinise the Scottish Ministers’ decision to consent before consent is given.

The section 57 process requires notification only after the consent has been given and accordingly is not appropriate for these circumstances.

The Committee recommends that there should be a process whereby the Parliament has an opportunity to scrutinise the Scottish Ministers’ position before they grant their consent.

The second issue relates to the Scottish Parliament’s scrutiny of instruments in devolved areas, or areas with a significant impact on Scottish interests, which have been laid in the UK Parliament.

The Scottish Parliament generally has no role in relation to the scrutiny of secondary legislation passed by UK Ministers acting alone. With primary legislation making provision in devolved areas, the Sewel Convention would apply. However, that Convention is not applicable to secondary legislation. The Bill does not create such a process.

The Committee considers that the Scottish Parliament should have a role in the scrutiny of such secondary legislation under the EU (Withdrawal) Bill.

One option would be to build into the Bill a process for the Scottish Parliament to be required to give its consent to the making of secondary legislation in devolved areas in a manner similar to that which it does for primary legislation.

Another option would be to require Ministers to lay instruments making provision in devolved areas in both the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament, enabling both Parliaments to scrutinise the instrument and both Parliaments to have a veto over the instrument. (The Bill provides for such a procedure but does not make it mandatory.)

The Committee notes however that both these options are likely to present challenges in light of the limited time which will be available to pass the necessary subordinate legislation before exit day.

The Committee would add that it envisages full dual Parliamentary scrutiny being required only in areas of significance. Provided the Scottish Parliament is afforded the opportunity for effective advance scrutiny of the Scottish Ministers’ choice to consent to UK Ministers legislating in devolved areas (as recommended in paragraphs 112 to 115 above), dual Parliamentary scrutiny could be reserved for those areas of particular significance.

Recommendation

The Committee believes that there should be a meaningful role for the Scottish Parliament in scrutinising UK instruments making provision in devolved areas or with a significant impact on Scottish interests and that role should be capable of affecting the legislation. It urges the UK and Scottish Government to reflect further on how that can be achieved within the applicable time constraints, and to work with the Scottish Parliament to find appropriate solutions. This is an area which the Committee is likely to revisit in its further consideration of the Bill.

Regulations made by the Scottish Ministers acting alone and laid in the Scottish Parliament

As noted earlier, the powers conferred on the Scottish Ministers are subject to some restrictions. Nonetheless within the confines of these restrictions the Scottish Ministers may make secondary legislation acting alone.

This route provides different challenges. At this stage with so much uncertainty about the volume and types of regulations that will be laid in the Scottish Parliament it is impossible to offer any definitive views on the challenges that lie ahead or the solutions to those challenges.

In the meantime the Committee has considered some of the challenges that might arise out of large numbers of instruments being laid in the Scottish Parliament.

The Committee explored with witnesses what the Scottish Parliament should be doing to prepare for this potential large increase in secondary legislation as well as what types of legislation it should be prioritising.

The Law Society of Scotland recognised that there may be a challenge with the volume of legislation to be made under the Bill and suggested:

“The creation of new bodies and associated expenditure, and issues that are raised in the bill that would normally attract the affirmative resolution procedure, could be prioritised. The House of Lords Constitution Committee suggested that that could be broadened to include a considerable degree of scrutiny in respect of issues of “significant policy interest or principle” that the Scottish Parliament would see as being of value to it.”i

Professor Tierney suggested that what is prioritised really depends on what Governments intend to do with the powers. As already noted, the UK Government has intimated that it will not use the powers to make significant policy changes. He pointed out that if it keeps to its commitment and the powers are used only to correct deficiencies to make legislation fit for purpose in the act of bringing it into UK law then the issue of prioritisation is less profound. He suggested the focus should be on ensuring that Ministers do not break that commitment.ii

Recommendations

The Committee agrees with Professor Tierney that the Scottish Ministers should not be using the powers to make policy changes and the Parliament should be policing that.

The Committee also recognises that there is a strong probability that some instruments will be more than technical, tidying up instruments. There is the potential for large volumes of instruments to be laid and there needs to be a process for these significant instruments to be identified and submitted to greater scrutiny.

The Committee recognises the practical reality that, when dealing with high volumes of EU-related SSIs, Scottish Parliament committees may wish to have as clear an indication as possible of which instruments are likely to be most significant. Committees will also have to balance the consideration of legislation relating to EU withdrawal with the domestic legislative programme. The Committee considers that it would be valuable to lead committees for EU withdrawal instruments to be ‘flagged’ where the instruments meet certain criteria. This is a role which could be carried out by this Committee.

It is expected that the Scottish Government may wish to provide, in addition to the usual Explanatory and Policy Notes, an assessment of the way in which each instrument modifies EU law, and of whether in doing so it goes no further than necessary to deliver the policy intention of the Bill. The UK Government has already made a commitment to include such a statement in Explanatory Memoranda for SIs. With such information, the Committee could, when considering individual SSIs, provide an indication to lead committees of the extent to which this Committee agrees with the Scottish Government’s assessment of the effect of the instrument. If the Committee identifies a discrepancy, lead committees could then decide what further scrutiny they would wish to undertake.

The Committee considers that it is critical for the “flagging process” for instruments to be supported by detailed accompanying information. The Committee explored with witnesses what this accompanying information should entail.

Professor Page made some suggestions:

“That should include the background to it; what it is designed to achieve; what the result will be; why it is being done that way; and what sort of scrutiny it is proposed to be subject to. All that information should be required, and the requirement should be policed.”iii

The Law Society of Scotland also made suggestions:

“…we suggest that it would be useful for ministers to specify in the explanatory notes to any instrument exactly what the instrument achieves and, if it is intended to amend existing legislation, why it is necessary and whether it makes a policy or purely technical change.”iv

Recommendations

The Committee’s position is that instruments should be accompanied by essential information (as noted below) to enable the subordinate legislation project for EU withdrawal to be delivered on time and with an appropriate level of scrutiny by the Parliament. It considers that each instrument should be accompanied by a succinct overview of the following matters (although this is not an exclusive list):

an explanation of the existing EU law,

the reasons for and effect of the proposed change,

a summary of the consultation carried out,

a statement explaining why the Minister considers the change appropriate (or necessary),

an indication of how the instrument should be categorised in relation to the significance of the change proposed,

the effect of the instrument in relation to Scotland.

It is also critical to the scrutiny of instruments that this Parliament has a clear indication of what is coming forward. To that end, the Committee reiterates its request to the Scottish Government to provide detailed and accurate information on forthcoming instruments as soon as it is in a position to do so.

The Committee also encourages the Scottish Government to take steps to ensure a steady flow of subordinate legislation to the Parliament, while recognising the challenges posed by the anticipated need in many cases for UK Parliament legislation to be laid first.

Regulations made by UK Ministers and Scottish Ministers acting jointly and laid in both Parliaments

Where the Bill confers powers on the Scottish Ministers, UK Ministers also have powers to act jointly with the Scottish Ministers. In such cases, the subordinate legislation is considered by both the Scottish and UK Parliaments. The Bill does not regulate how decisions are to be made as to where it would be appropriate for UK and Scottish Ministers to act jointly, and there is no formal role for the Scottish Parliament to scrutinise the choice made.

Charles Mullin, giving evidence on behalf of the Law Society of Scotland, highlighted that it was unclear the circumstances in which this approach would be adopted and contrasted that with the Scotland Act 1998 where it is clear when concurrent powers are to be exercised.

Professor Page went further and suggested that it was unlikely that this route would be pursued:

“Of the three possible routes, I would leave to one side the joint exercise of powers. I regard that as a non-starter, if only because it would require scrutiny and approval in two Parliaments.”i

Chris Skidmore MP explained why provision had been made for it:

“At the moment, it provides a mechanism for allowing the devolved legislatures to scrutinise legislation. It is likely to be used when a devolved Administration requests that the UK Government legislate on its behalf but the appropriate change in order to retain EU law is so significant that we agree that it would be appropriate for the relevant devolved legislature to scrutinise the regulations, too.”ii

He highlighted that this approach has been taken in relation to the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017, which consolidated existing legislation and implemented EU obligations to provide a common strategic framework for the protection of the water environment in England and Wales.

He further suggested that it was a new process and how it would be used was evolving.

Recommendation

The Committee notes the Minister’s comments on the use of the joint procedure. The Committee notes, however, that this is not a new procedure for the Scottish Parliament and that one already exists in the Scotland Act 1998. The Committee can see value in a procedure for joint scrutiny where matters are of such significance. The Committee would welcome further clarity on the circumstances in which such a procedure might be used.

Scrutiny procedure

Having considered the powers themselves the Committee reflected on the level of scrutiny attached to the powers.

The Scottish Ministers’ powers to deal with deficiencies, remedy breaches of international law and implement the withdrawal agreement are subject to affirmative procedure where the power is used to:

Establish a new public authority

Transfer an EU function to a newly created public authority

Transfer an EU legislative function to a public authority

Make provision relating to fees

Create or widen the scope of a criminal offence

Create or amend a power to legislate. (Sch.7, para. 1(4))

In every other case negative procedure can be used, but Ministers have the choice to apply affirmative procedure (Sch. 7, para. 1(5)). It is for the Scottish Ministers to determine which to use and then to account to the Parliament for that choice. This operates in the same way as the current power in section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972.

Equivalent affirmative and negative procedures are provided for regulations made by UK Ministers, Welsh Ministers and Northern Ireland departments, and for regulations made jointly by UK Ministers and devolved authorities.

Affirmative vs negative procedure

The Committee considered the balance in the Bill in terms of what is subject to negative procedure and what is subject to affirmative procedure. The Committee explored with witnesses whether the right balance had been struck.

Professor Page suggested to the Committee that a “minimalist” approach had been taken to what must be subject to affirmative procedure. He further suggested that the decision as to what procedure an instrument should be subject to should be a matter for Parliament rather than Ministers, that Parliament should not always be on “the receiving end of decisions”.

Professor Tierney was clear that the right balance had not been struck and that a wider range of subjects should be required to be dealt with by instruments subject to the affirmative procedure. At the same time, he suggested that the volume of work to be done and the limited timeframe in which to do it, probably means that applying the affirmative procedure to more provisions of the Bill would be challenging.

The House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee expressed concern about the narrow range of matters that must be subject to the affirmative procedure.

In particular, it highlighted its concern about the negative procedure being applied to regulations amending primary legislation.i

Furthermore, under Schedule 7, the affirmative procedure is required where the regulations provide for any function of an EU body to be exercisable by a newly-established body under clauses 7 to 9. However, where regulations transfer such functions to an existing body the negative procedure can apply. The Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee expressed concern about this too:

“We are not convinced that there are sound reasons for this difference in approach. The issues of how transferred functions should be configured in a UK context, and which body is most appropriate to exercise particular functions, are of equal importance in both cases, and arguably justify the affirmative procedure in both cases.

It is suggested in paragraph 47(a) and (b) of the delegated powers memorandum that a higher level of scrutiny is appropriate where functions are transferred to a newly-established body because of the cost implications of setting up the new body. There will be cost implications arising from the transfer of functions (and how those functions are configured) whether it is a new or old body that is given the functions. And in any case that seems to us to be an unduly narrow basis for determining whether the affirmative procedure should apply.”i

Recommendations

The Committee notes the concerns expressed by the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee about the insufficient range of matters that must be subject to the affirmative procedure. The Committee also notes that committee’s suggestion that the affirmative procedure should be applied to regulations which transfer functions from an EU body to an existing UK body.

The Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee also recommended that regulations amending or repealing primary legislation should be subject to the affirmative procedure.

The Committee understands from the Delegated Powers Memorandum that changes to primary legislation using the secondary legislation powers in the Bill are intended to be minor and mechanistic. If that is the case then the negative procedure may be the right one. However the Bill as drafted, as the Committee has commented on already, also enables substantive changes to be made to primary legislation in instruments subject to the negative procedure.

The Committee considers that the starting point in considering delegated powers is that regulations amending primary legislation should be subject to the affirmative procedure. However it recognises that powers must be considered in the context of the Bill in which they arise. The context here is that the EU withdrawal project is likely to require numerous minor amendments to be made to primary legislation.

The Committee is of the view that the Scottish Parliament’s processes for the scrutiny of secondary legislation are robust and allow for effective scrutiny of instruments irrespective of the procedure attached to them.

However, the Committee recognises that where Ministers have a choice as to which procedure to adopt they will most likely choose the procedure subject to a lower level of scrutiny. The Committee would be concerned if the powers were exercised to make substantive policy changes to primary legislation using the negative procedure.

The Committee suggests that further work should be done to identify further categories of significant actions or impacts which ought to attract the affirmative procedure, in addition to those in the Schedule 7 list. It may be possible for these to be identified on an informal basis, without the need to be written into the Bill.

Enhanced procedure

The Committee also examined whether there should be provision for an enhanced form of affirmative procedure on the face of the Bill to attach to instruments making particularly significant provisions.

Scottish Environment Link suggested to the Committee that this would be one way of maximising the opportunity for stakeholders to engage in the development of regulations.

Professor Tierney suggested that there would be value in such a procedure, but at the same time made the point that the Bill really should not be used for matters that would prompt the need for an enhanced form of affirmative procedure. The real issue, he said, was that the Bill should be constrained in a way that such significant matters cannot be pursued under it.i

Recommendations

The Committee recognises that the timescales for making instruments prior to exit day may make the use of an enhanced scrutiny procedure deeply challenging from a practical perspective.

Nonetheless the Committee can see that if the powers continue to be as wide as currently drafted there could be an argument for making provision for such a procedure. The Committee also notes that this would have the benefit of enabling stakeholders as well as the Parliament to engage in the development of regulations.

The Committee also recommends that, in the interests of good scrutiny and allowing stakeholders to engage, the Scottish Government should publish drafts of regulations for consultation as soon as they are ready. The Committee encourages the Scottish Government to do so as soon as practicable.

Made affirmative procedure

The proposed scrutiny procedures for all the powers are set out in Schedule 7, Parts 1 and 2.

The Schedule provides for a made affirmative procedure to apply to instruments made under powers conferred on UK Ministers in certain urgent cases.

The made affirmative procedure enables Ministers to make legislation before it is approved by Parliament. After making it must be laid before Parliament for approval. The approval must be given within one month of laying otherwise the instrument ceases to have effect.

The Delegated Powers Memorandum explains the need for this urgent procedure:

“The made affirmative procedure will be available as a contingency should there be insufficient time for the draft affirmative procedure for certain instruments before exit day. … The Government believes that the exceptional circumstances of withdrawing from the EU might necessitate the use of the made affirmative procedure.”

This procedure is currently only available to UK Ministers.

The Committee asked Michael Russell MSP whether the Scottish Ministers would be seeking this procedure. The Minister suggested that he was unclear as to why UK Ministers had taken this procedure and in what circumstances they envisaged making use of it. Once sure of its purpose, however, the Minister suggested that the Scottish Ministers may wish to have an equivalent procedure.

Given the Minister’s comments the Committee explored with UK Ministers the circumstances in which the procedure might be used.

The Committee notes, however, that the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution raised concern about the use of this power:

“We acknowledge that there are likely to be significant time pressures for the Government delivering the secondary legislation required to facilitate legal continuity upon exit. We also acknowledge that regulations made by way of the ‘made affirmative’ procedure are time-limited in their effect. However, given the significance of the issues at stake, and the breadth of the powers involved, we are not convinced that urgent procedures are acceptable.”i

Robin Walker MP suggested to the Committee that he was willing to listen to views on whether it would be valuable for the Scottish Ministers to have this procedure. He suggested that it had not been included as it was for the Scottish Parliament to set its own procedures.ii

Recommendations

The Committee considers that there could be merit in such a procedure being available for affirmative regulations laid in the Scottish Parliament. It appears that the Scottish Ministers are just as likely, if not more likely, to have to make urgent instruments as the UK Ministers. For example, there may be circumstances where the Scottish Ministers will have to wait to see an approach taken by UK Ministers before making instruments, due to the requirement for Scottish Ministers to legislate consistently with modifications made to certain retained EU law by UK Ministers. Accordingly the time for the Scottish Ministers to make instruments may be even more constrained.

However, the Committee notes the concerns expressed by the Constitution Committee about the use of this procedure.

The Committee suggests that bringing secondary legislation into force without prior parliamentary scrutiny should not become common practice. It considers that a case by case analysis of the appropriateness of procedures for making legislation without prior parliamentary scrutiny is needed.

In relation to this Bill, the Committee recognises that the need to plug gaps quickly in order to provide certainty and resolve problems which arise for stakeholders, may in some circumstances make the use of a made affirmative procedure suitable. Nonetheless, any such urgent procedures should only be used where necessary and should not be an alternative to thorough planning and timetabling.

Setting of the procedure

The Committee has reflected on the issue of who should be setting the procedure for regulations. As noted earlier, the Bill specifies certain circumstances where the affirmative procedure must apply, but otherwise it is open to Ministers to decide what procedure should be attached to an instrument.

In its report, The ‘Great Repeal Bill’ and delegated powers,i the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution recommended that, instead of the Bill stating which procedure the secondary legislation should follow, the UK Government should issue an explanatory note for each piece of secondary legislation which makes a recommendation as to the appropriate level of parliamentary scrutiny that it should undergo.

The UK Government has not followed this recommendation.

Professor Page suggested to the Committee that the decision on the choice of procedure ought not to be taken by Ministers alone and there should be a parliamentary committee contributing to that decision.

The Law Society of Scotland echoed Professor Page’s view and highlighted the Constitution Committee’s report:

“…it is worth while to add that we looked at a House of Lords select committee’s suggestion of a triage procedure, whereby a minister would specify exactly what his regulations would do and the relevant Parliament could then assess whether it agreed with the level of scrutiny that was being proposed by the minister. The procedure would allow for regulations to be considered under affirmative procedure rather than negative procedure, when the Parliament considered that to be appropriate.”ii

Michael Russell MSP expressed a willingness to work with the Parliament on the design of scrutiny procedures and advised the Committee that work was ongoing to develop such mechanisms.

Recommendations

The Committee considers that Scottish Ministers should not be setting the procedure for instruments without the involvement of the Parliament.

The Committee believes that there should be a process to allow this Parliament to require the Scottish Government to lay a proposed instrument under the affirmative rather than the negative procedure. This reflects the principle that the Parliament should be consulted on significant issues before they can come into force, given that annulment of a negative instrument is not always an option, depending on whether the instrument has already taken effect.

On the basis of the information currently available, the Committee does not think it necessary to establish a new committee to undertake the function of considering the appropriate procedure for an instrument. However given the anticipated volume of instruments, the Parliament may need to apply its existing processes in new and flexible ways.

The Committee also encourages the Scottish Government to share information as early as possible about the instruments it intends to bring forward and the scrutiny procedure to be attached to them. The Committee recognises that this is impossible at the moment, but such information should be shared with the Parliament at the earliest possible opportunity to enable the Parliament to plan effectively for the laying of instruments and to identify any obvious anomalies in the proposed procedure to be attached to an instrument.

The Committee’s recommendations here underline the importance of further work being done to agree categories of significant actions or impacts which ought to attract the affirmative procedure, as recommended at paragraph 163 above.

Stakeholder involvement

The Scottish Parliament was founded on the basis of four key principles:

Accountable

The Scottish Parliament is answerable to the people of Scotland. The Scottish Parliament should hold the Scottish Government to account.

Open and Encourage participation

The Scottish Parliament should be accessible and involve the people of Scotland in its decisions as much as possible.

Power Sharing

Power should be shared among the Scottish Government, the Scottish Parliament and the people of Scotland.

Equal Opportunities

The Scottish Parliament should treat all people fairly.

At the heart of all of these is a sharing of power with the people of Scotland.

Daphne Vlastari of Scottish Environment Link reflected to the Committee why public involvement is so important in this process:

“As we move forward, different statutory instruments will need to be looked at, and frameworks will be considered for potential UK implementation. We would like a clear mandate for transparency in scrutiny through the involvement of Parliament and substantive stakeholder engagement. We highlight the fact that the joint communiqué, which was mentioned in the previous evidence session, makes no reference to stakeholder engagement. Unless there is a public and transparent dialogue, we will not get the best legislative outcomes.”i

Legislation made under this Bill is likely to be voluminous, complex and undertaken within a very tight timeframe.

The Scottish Parliament must do all it can to make sure that stakeholders can engage with it and help shape the secondary legislation made under this Bill. In a drive for pragmatism, the opportunity for stakeholder engagement should not be lost. As Daphne Vlastari pointed out, without stakeholder engagement the best legislation will not result.

Recommendations

The Committee reiterates its recommendation that, wherever possible, regulations should be submitted for consultation as early as possible. While some regulations may need to wait on the outcome of exit negotiations others can be progressed now and should be, so as to enable that stakeholder engagement.

The Parliament should also do what it can to publicise opportunities to engage with secondary legislation as well as explaining the process for the scrutiny of secondary legislation to help people understand when the opportunities for engagement and influence exist.

Further scrutiny of the Bill

Recommendation

The Committee welcomes the fact that both the UK Government and Scottish Ministers have commissioned their officials to work together to find solutions to some of the matters arising in relation to powers and scrutiny processes under the Bill which affect the workability of the Bill. The Committee will watch the progress which is made and hopes the suggestions it makes in this report will aid that process and welcomes the involvement of Scottish Parliamentary officials in that process. It also anticipates that the Bill will be significantly changed following amendments. Finally, while the Committee considers that the Parliament’s procedures for scrutinising secondary legislation are robust, the Committee will continue to reflect on those processes as further information emerges about the timing and scale of the subordinate legislation project under the Bill. The Committee intends to revisit the Bill and reflect further on all these issues.

List of Recommendations

The Committee makes the following recommendations:

Broad Powers

The Committee reluctantly accepts that the unprecedented task of modifying domestic legislation to preserve the statute book on leaving the European Union, and the short timeframe in which it is to be done, necessitates broad powers. In any other circumstances the conferral of such wide powers would be inconceivable, but the Committee accepts that in these circumstances the taking of wide powers is unavoidable.

However, the Committee considers that the powers should only be available where Ministers can show that it is necessary to make a change to the statute book, even if they cannot show that the particular alternative chosen is itself necessary.

The Committee notes that Ministers confirmed that the powers are not to be used to make policy changes. The Committee welcomes this. The powers should not be used to make substantive policy changes.

The Committee acknowledges that Ministers need to be able to make choices between alternative options where a change is required in order to remedy a deficiency in EU law. It is the Parliament’s role to scrutinise that choice.

However, the Committee recommends that Ministers consider further the suggestion made by other committees that the powers should be based on a necessity test rather than an appropriateness test. It anticipates that it should be possible to find some wording which would restrict Ministers to using the power only where necessary, while still enabling a choice to be made between competing solutions depending on which is most appropriate.

Protection of Constitutional Statutes

The Committee supports the concept of a constitutional protection clause. The Committee understands the justification for providing specific protection to the Northern Ireland Act, however, the Committee equally believes that protection should also be afforded to other constitutional statutes including the Scotland Act 1998.

At the same time, the Committee recognises that the Scotland Act 1998 is already amendable by way of secondary legislation. Significant amendments made to that Act by secondary legislation, such as changes to competence or to Ministers’ functions are, however, subject to scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament.

It is not appropriate that matters of such constitutional import should be amendable by secondary legislation that is subject to scrutiny in the UK Parliament alone. Where it is considered necessary to amend constitutional statutes such as the Scotland Acts this should be done in a way which is subject to thorough and meaningful scrutiny in this Parliament.

Powers not available to the Scottish Ministers

Clause 17: Powers to make consequential and transitional provision

The Committee recognises that ancillary powers of this nature have the potential to have far-reaching effects. The need for their inclusion in a bill has to be made out on a case by case basis.

At the same time, the Committee can see the potential for gaps to arise as a consequence of this Bill in areas of legislation which solely affect the Scottish Parliament or the powers of the Scottish Ministers. An example might be in the statutory codes of interpretation which apply to Acts of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish statutory instruments. These gaps may not become clear until after the Bill is in force.

The Committee recommends that further thought be given to the question of whether powers equivalent to those in clause 17 be conferred on the Scottish Ministers, to enable them to plug any gaps arising as a consequence of the Bill or in relation to transition to the new regime, within Ministers’ extended legislative competence as conferred by this Bill. Such an approach would enable the exercise of these ancillary powers to be scrutinised in the Scottish Parliament.

Restrictions on the Scottish Ministers’ powers

The Committee notes that this is an immensely important issue and one that is at the heart of shaping how common frameworks will work. This is a policy issue.

The Committee appreciates that the Finance and Constitution Committee is considering the issues around common frameworks and accordingly draws that Committee’s attention to the evidence this Committee has taken on the issue.

Fees and Charges

The Committee expresses its concern about the ability of Ministers to impose taxation measures in regulations made under Schedule 4.

It also agrees with the conclusions of the House of Lord’s Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee regarding sub-delegation of this power. Ministers should not be able to sub-delegate the power to create fees or charges to a public body, enabling that body to impose those fees or charges administratively rather than by way of statutory instrument. It appears to the Committee that sub-delegating the power to charge fees in this way will not create the transparency and certainty which business is seeking following EU withdrawal.

The Committee also echoes the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee’s recommendation that the affirmative procedure should apply to all regulations under Schedule 4 which introduce or increase fees. This Committee has consistently in its various reports on delegated powers made the point that applying the affirmative procedure to the first use of a power, and the negative procedure to subsequent uses, is unacceptable in principle. In this case such an approach would allow an initially very small fee to be set by affirmative regulations, with a subsequent significant increase imposed by negative regulations.

Legislative routes

Where there is scope for secondary legislation to be made following different routes there must be clarity on which route is being pursued and why. The Committee believes that co-operation and co-ordination between governments is essential to the effective delivery of secondary legislation under the Bill. Co-ordination and co-operation between governments should, however, be in addition to and not a substitute for effective scrutiny of secondary legislation by the UK Parliament and devolved legislatures. It is for the legislatures to scrutinise that co-ordination and co-operation, and the decisions which flow from it.

Essential to that effective scrutiny is co-operation and coordination between legislatures.

Regulations made by UK Ministers acting alone and laid in the UK Parliament