COVID-19 Recovery Committee

Road to recovery: the impact of the pandemic on Scotland's labour market

Executive summary

The COVID-19 Recovery Committee launched this inquiry to consider what impact COVID-19 has had on long-term illness and early retirement as drivers of economic inactivity. The Committee found that although the pandemic has not had a significant impact on economic inactivity in Scotland, it has starkly highlighted the extent to which a healthy working-age population is required to sustain a healthy economy. In the COVID-19 recovery period, the Scottish Government should work with employers to support more investment in employees’ wellbeing and embed post-pandemic opportunities for flexible working. These measures are likely to bring more people into the labour market and support the preventative healthcare agenda.

Mental health and chronic pain are having the biggest impact on economic inactivity rates in Scotland. Indeed, the Scottish Government estimates poor mental health currently costs Scottish employers more than £2 billion annually. Yet it does not appear to be widely understood that for every £1 employers invest in mental health support for their employees, they will receive an estimated £5 return on their investment. Encouraging greater investment in this area is likely to support a more resilient workforce for the future and be particularly beneficial in sectors where employees are experiencing lasting pressures from the pandemic, such as health and social care.

COVID-19 has driven a rapid acceleration in societal changes to the way many people work, including realising opportunities for remote working, as well as flexible working practices, such as compressed hours, part-time hours, job-share etc. The Committee heard that implementing remote and/or flexible working practices may improve employees’ wellbeing, bring more people into the labour market, including disabled people and people with chronic or mental illness, and support older workers to remain in the labour market for longer. But many employers, particularly small and medium enterprises, require support to implement flexible working and reasonable adjustment policies.

The Scottish Government’s Centre for Workplace Transformation is a laudable policy ambition to embed some of the learning gained from the pandemic on these issues. Notwithstanding current inflationary pressures on the Scottish budget, the Committee was disappointed to learn that this policy commitment has not been delivered within the 2022 target. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to clarify its plans for delivering this policy ambition, including the costings and delivery options that it has explored.

For working-aged people who are far away from the labour market, wrap-around employability services, like the Fair Start Scotland programme, provide tailored support to get people into employment. Good work is being done using this and other employability programmes, but the Committee considers that the Scottish Government could do more to ensure best practice is shared and implemented across all local authorities.

The pandemic has also shown that Scotland has the potential to be a world-leader in using health data to inform public policymaking, including policies aimed at tackling economic inactivity and its underlying causes. The Committee heard in evidence that the biggest barriers to realising this ambition appear to be a lack of "instruction, resources and permissions". The Scottish Government should capitalise on and invest in the advances made in health data analysis during the pandemic to underpin the delivery of a wellbeing economy and the preventative health agenda.

The Committee is keen to better understand the public health support available to people experiencing Long COVID and has therefore decided to consider this further in a separate inquiry to be launched in 2023.

Introduction

The COVID-19 Recovery Committee launched this inquiry to consider what impact COVID-19 has had on long-term illness and early retirement as drivers of economic inactivity. The Committee chose to focus on long-term illness because it was interested in considering what health impacts the pandemic has had on people’s ability to work, including Long COVID, mental health and other chronic illnesses, and whether these have been made worse by the experience of the pandemic. The Committee also agreed to consider how the pandemic impacted on older workers’ attitudes to employment and the factors that influence some people to take early retirement.

The Committee received 45 responses to its call for views, which was open from 30 June 2022 to 9 September 2022.i The Committee took evidence from witnesses during four evidence sessions on 3 November 2022; 10 November 2022; 17 November 2022 and 8 December 2022. A list of the additional written evidence that was submitted by witnesses is provided in the annexe to this report.

The Committee was interested to speak with people who were not working, either due to a long-term health condition or because they had taken early retirement since 2020. People with experience of these issues met with the Committee in an online discussion on Thursday, 24 November. On Monday 28 November, the Committee visited Airdrie to speak with Remploy and Routes to Work, their service users and partners to understand what services they are providing to support people with a long-term illness who wish to get into employment in North Lanarkshire. A note of the discussion from these engagement activities is provided in the annexe to this report.

The Committee would like to thank everyone who participated in the inquiry. The discussions it held and the evidence it received greatly informed the Committee’s understanding of the key issues in this inquiry and helped shape its recommendations to the Scottish Government.

This report also makes reference to labour market data that were considered in the course of the inquiry, which included data for the period up until its final evidence session on 8 December 2022. The Committee acknowledges that the labour market data for the very short term is fluid and is informed by various factors, meaning it can be challenging to draw definitive conclusions about trends and the causes and effects of the data presented at a single point in time.ii The Committee has therefore sought to hear from witnesses with a diversity of viewpoints, expertise and lived experience to provide it with an understanding of the trends evident at the time of its inquiry. Its recommendations are based on this understanding.

Economic inactivity: a new phenomenon, or not?

In the working-age population (people aged 16 and over, up to those aged 65), a person's economic status is generally classified into one of three categories: employed; unemployed or economically inactive. Economic inactivity is defined as people aged 16 and over without a job who have not sought work in the last four weeks and/or are not available to start work in the next two weeks.i The reasons why people may not be available for work include being temporarily sick or injured, long-term sick or disabled. Other reasons include taking early retirement, having caring responsibilities or studying. The reasons for a person's economic inactivity can also be overlapping, for example a person may take early retirement due to ill-health. Economic inactivity is distinguished from people who are unemployed, which is defined as people who are without a job, have been actively seeking work in the past four weeks and are available to start work in the next two weeks; or who are out of work, have found a job and are waiting to start it in the next two weeks.i

Data from the Labour Force Survey show that the economic inactivity rate had generally been falling in the UK since comparable records began in 1971.i The COVID-19 pandemic, however, appeared to reverse this trend and led to an increase in overall economic inactivity in the UK.i This appears to have emerged as a distinctive issue for the UK economy's recovery from the impacts of COVID-19.v The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has reported, for example, that increased inactivity experienced toward the start of the coronavirus pandemic appears to have been more persistent in the UK compared to other G7 countries.i An analysis of 37 countries by the Financial Times also found that the UK was the only country where levels of economic inactivity had not recovered to their pre-pandemic level.vii These factors have therefore highlighted economic inactivity as a particular challenge in the post-COVID recovery period compared to previous economic shocks in the UK.i

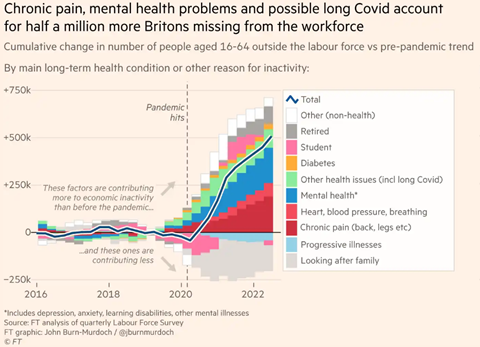

An analysis by the Financial Times shows that at a UK level there has been a steep rise in economic inactivity, particularly for people with certain health conditions, including chronic pain and mental health.i This is shown in Figure 1 below–

Figure 1 Excerpt from an analysis by the Financial Times on the cumulative change in number of people aged 16-64 outside the labour force versus pre-pandemic trend by main long-term health condition or other reason for inactivity Financial Times analysis of quarterly Labour Force Surveyi

Financial Times analysis of quarterly Labour Force Surveyi

These findings have been widely reported and commented upon, with commentators coming to different conclusions about the various factors that may be responsible for the trends in the data.vii The analysis by the Financial Times, for example, suggested that treatment backlogs and wider pressures on the NHS may be driving the slow recovery from increased economic inactivity, noting that the number of people who have been on a waiting list for more than a year (332,000) is very similar to the number of people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness (309,000).vii However, this analysis does not include information on some factors that may inform the relationship between economic inactivity and waiting time data, such as how many people experiencing mental illness have sought treatment as an elective inpatient, or the number of people with chronic pain that require a procedure as part of their treatment plan.

The ONS explained in its written submission that UK-wide NHS waiting times have been growing, which is likely to be a contributing factor to the increase in economic inactivity due to illness in the UK.xiii Subsequently ONS research has found that one-fifth (18%) of 50–65-year-old people in the UK who became inactive during the pandemic and have not returned to the labour market are on an NHS waiting list.i

Inclusion Scotland commented on these ONS figures, noting that it is difficult to determine what relationship there is between waiting time data and economic inactivity.xv Inclusion Scotland stated that–

Those waiting for treatment do generally have lower employment rates than those receiving treatment (61.4% compared with 67.3%) but this suggests rather than increasing flows into inactivity, delays in treatment are moving people already out of work further from being able to begin returning to work. There is a risk that for people on sick leave awaiting treatment, or in self-employment unable to work, this situation worsens with time.xvi

The Committee also heard from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, whose recent commentary highlights that "the rise in the number of people who are inactive due to ill-health does not necessarily imply that all these people have left the labour force as a result of ill-health".xvii

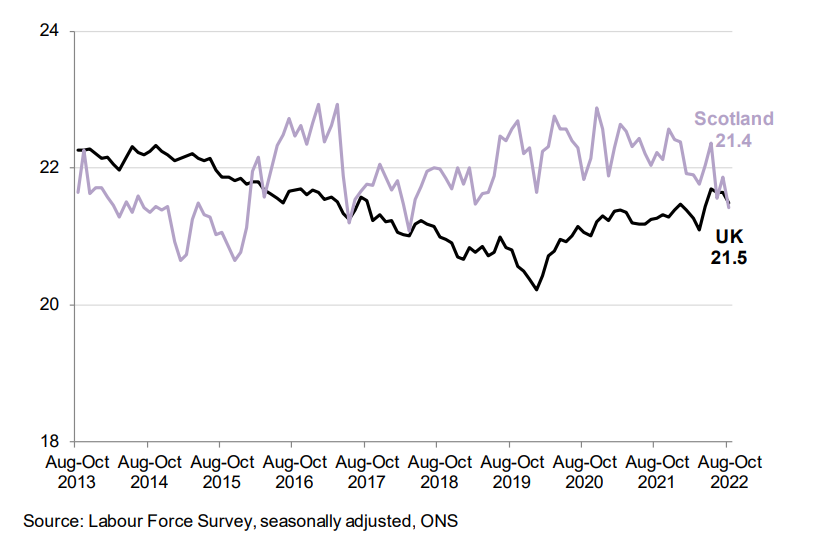

According to the Scottish Government's latest Labour Market Trends report, the estimated economic inactivity rate for people aged 16-64 years in Scotland was 21.4 per cent in August to October 2022 (compared to an estimated UK economic inactivity rate of 21.5 per cent). This is only 0.2 percentage points down on the Scottish figures for December 2019-February 2020 (pre-pandemic), as shown in Figure 2 below–

Figure 2 Economic inactivity rate for persons aged 16 to 64, Scotland and the UK Scottish Government Labour Market Trends: December 2022xviii

Scottish Government Labour Market Trends: December 2022xviii

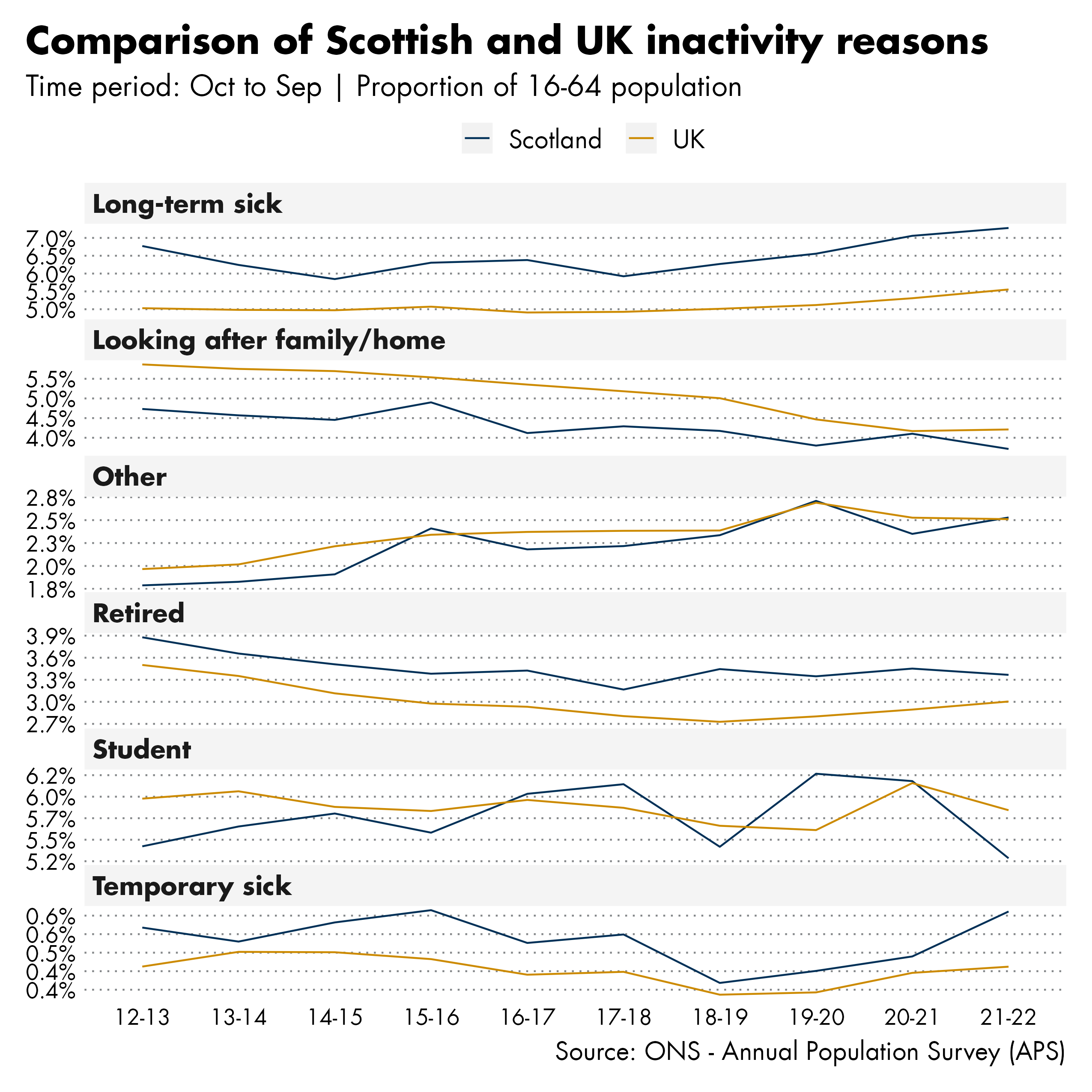

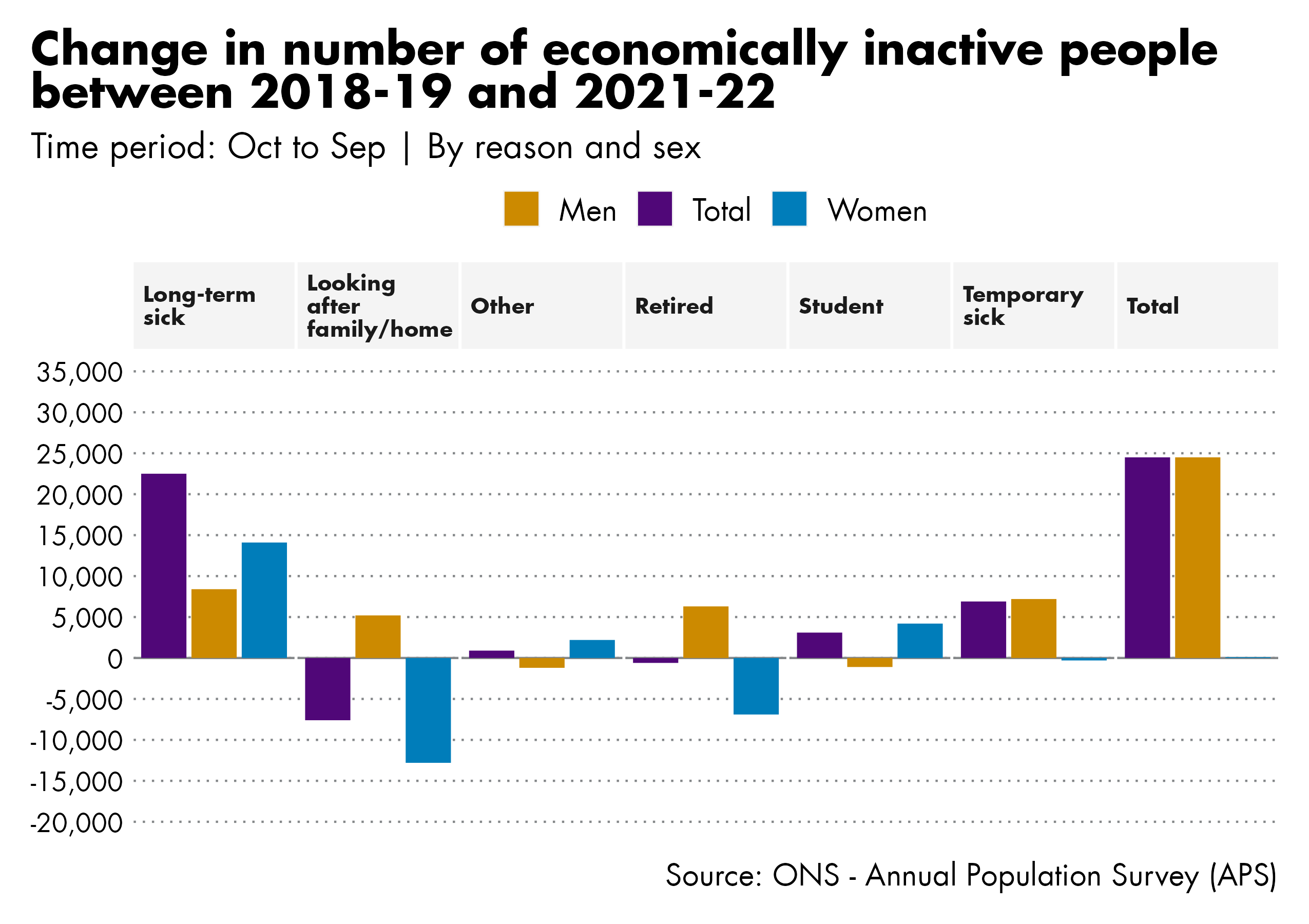

Figure 3 below shows in more detail the short-term pre- and post-pandemic reasons behind economic inactivity in Scotland and the UK–

Figure 3  Annual Population Surveyxix

Annual Population Surveyxix

According to the Annual Population Survey, the change in reasons given as to why people were inactive between Oct 2018-Sep 2019 and Oct 2021-Sep 2022 in Scotland shows that the largest increase was in the number of people who are long-term sick, with the figures for people who are short-term sick also seeing a large increase.xx Scotland also has a higher proportion of the 16-64 population who are inactive because they are long-term sick than that which applies across the whole of the UK. The proportion of the 16 to 64 population who are inactive and long-term sick has been increasing for both Scotland and the UK since 2016-17. However, in Scotland it has increased from 6.3% to 7.3% percent of the 16 to 64 population during this period, compared to 5.0% to 5.6% for the UK.xix The Committee also considered those who are inactive because they have taken early retirement. The proportion of the 16-64 population who are retired in Scotland has remained around 3.4% since Oct 2014-Sep 2015.xix

Since the Committee launched its inquiry, there has been an increased focus from government and the media on the pressures within the NHS in Scotland, including waiting time data.xxiii The most recent Public Health Scotland data for the quarter ending on 30 September 2022 shows there were 35,337 people who had been on a waiting list for over a year.i Since September 2019 the number of people waiting for a year or more has increased by around 34,000.i The Annual Population Survey data show that between the year ending September 2019 and the year ending September 2022 the number of long-term sick has increased by around 34,000.xix However, the Committee notes that caution should be exercised when interpreting this data, as while there may be a correlation, there may not be a direct link between the data sources. The coverage of the two datasets also differs. For example, those on waiting lists can include children, individuals who are still in work or retired, while the economic inactivity data relates to those of working age. Furthermore, as the data from the Annual Population Survey is taken from a survey, there is an element of uncertainty in its accuracy, especially for smaller populations groups such as the long-term sick. The Committee notes that another issue to consider when interpreting the data is the way in which it is collected, with the waiting list data based on administrative data from the NHS, while the inactivity data for long-term sickness is self-reported.

The Committee heard that long-standing issues also inform the short-term economic inactivity data in Scotland, particularly in relation to long-term illness. Professor Steve Fothergill, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, National Director, Industrial Communities Alliance, told the Committee that the so-called “the mining area phenomenon” has played a role in long-term economic inactivity figures. This describes a trend in people leaving the labour market and moving onto sickness and disability benefits in former mining communities from the 1980s onwards.viii Professor Fothergill explained that this phenomenon has since become intergenerational in some parts of Scotland, as well as in other parts of the UK. According to Professor Fothergill, this has accounted for a rise in working-age people on disability benefits in the UK from approximately 750,000 people in the late 1970s to 2.5 million people in the present day.viii

Professor Gerry McCartney, Professor of Wellbeing Economy, University of Glasgow, informed the Committee that “Scotland’s health in comparison with that of the rest of the UK was improving on average until around 2010 or 2012, albeit that it had always been worse comparatively”.viii Professor McCartney explained that Scottish research has shown the reasons behind this longer-term trend in comparable health outcomes include adverse exposure to poverty, deprivation and deindustrialisation.xxx In the period from 2011 to immediately prior to the pandemic, Professor McCartney noted that improvements in population health had begun to reverse, such that average healthy life expectancy had declined by two years. In the most deprived 20 per cent of the population, healthy life expectancy declined by three and a half years.viii

The Scottish Government told the Committee that in its view “Scotland’s inactivity rate is not a significant outlier in comparison with the United Kingdom or other countries, but our population is increasingly older and less healthy, and inactivity has increased over a number of years…”viii The Scottish Government also acknowledged that “…health and health services are enormously important, but noted that “…the drivers of inactivity overall can be complex and multifaceted and vary for each person. We cannot take a one-size-fits-all approach to the problem or the solutions.”viii

The Committee notes that that overall rates of economic inactivity in Scotland remained variable during the pandemic. The factors influencing economic inactivity, including waiting times data, are complex. The Committee has considered the impact of long-term illness, including Long COVID, and early retirement as reasons behind economic inactivity in more detail below.

Economic inactivity and illness

The Committee held two engagement sessions to understand the barriers to employment and support available for people who experience mental illness or other long-term health conditions. On 24 November 2022, the Committee held an online discussion with people who have a long-term health condition. The Committee then visited Airdrie to speak with Remploy and Routes to Work, their service users and partners on Monday, 28 November 2022. The Committee focused on speaking with people who have experience of mental ill-health or a chronic illness (including long COVID) because these appear to be two of the most prevalent conditions amongst people who are not working due to ill health.

Mental health and wellbeing

The Committee heard that poor mental health and wellbeing are significant drivers behind economic inactivity. Whilst mental health and wellbeing issues in the population were prevalent prior the pandemic, it seems to have had a direct and lasting impact on many people’s mental health and wellbeing. The Committee heard that the ongoing effects of the pandemic include health-related anxiety about contracting COVID-19 in the workplace; social anxiety compounded by multiple lockdowns; reduced access to health and social care; burnout or other increased pressures at home or at work; and a loss of personal self-confidence from being made redundant during the pandemic.i

The Scottish Government agreed that there appears to have been a rise in people presenting with poor mental health and wellbeing since the pandemic began.ii This has been evident in increased activity in secondary care mental health services, which it suggested may be related to late presentation and periods of isolation resulting from the lockdowns.ii The Scottish Government explained that there has also been “a smaller but significant increase” in the prevalence of conditions, such as anxiety and depression among the wider population.ii

The Committee was informed that early prevention could avoid an estimated one third of people who have a chronic health condition from developing their chronic condition in the first place.ii However, witnesses noted that the healthcare system is currently focused on delivering ‘curative’ treatment, rather than public health approaches to prevention.ii The Scottish Government acknowledged the drawbacks of focusing on treatment over prevention in mental health services, noting that—

“Over the past decade, we have learned that, by continually investing in more and more services, all that we will see is demand continuing to rise at least equal to, if not ahead of, that service provision and our ability to provide it.”ii

The Scottish Government further explained that it is moving in the direction of rebalancing services to place a greater focus on preventative healthcare in specific service areas, including mental health, but this will take time and is difficult to achieve in a resource-constrained environment.ii

In the meantime, it was also suggested to the Committee that there are steps that can be taken to encourage and support employers to support positive mental health and wellbeing in the workplace.ix These measures can include direct and indirect investment in employee wellbeing. For example, the Committee heard that in some sectors where flexible working pilots have been led and supported by industry bodies, significant improvements in wellbeing have been demonstrated. The Construction Industry Training Board informed the Committee that it commissioned a Timewise: Designing Flexible Career Pathways in Construction Project in 2020. This project was designed to work with several major contractors and their supply chains to gain new insight into how to embed flexible working across all roles in the construction industry, with a view to producing a roadmap for industry-wide change. The project’s evaluation showed a 75% increase in a sense of wellbeing amongst participants and the percentage of participants who felt their working hours gave them enough time to look after their own health and wellbeing rose from 48% to 84%.x

The Committee was also encouraged to hear how effective employers’ direct investment in interventions in their employees’ health and wellbeing can be. The Scottish Government informed the Committee in this regard that “…poor mental health costs Scottish employers more than £2 billion a year at the moment, and that, for every £1 that is spent on mental health interventions, employers get a £5 return on investment.”ii The Scottish Government noted that resources are available to support positive mental wellbeing in the workplace, including a website called Healthy Working Lives.ii The Scottish Government also explained that its forthcoming mental health strategy will cover issues related to economic inactivity and employment.ii

The Committee notes the Scottish Government’s evidence that for every £1 that employers invest in mental health support for their employees, they will receive an estimated £5 return on their investment. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should prioritise raising awareness of this research and working with employers to invest more in mental wellbeing services.

The Committee also welcomes the work being led by some industry bodies on supporting the development of flexible working policies to support employee wellbeing. The Committee seeks clarification on what action the Scottish Government is taking to support industries to develop practical resources for employers to support the adoption of flexible working policies and share best practice.

Chronic illness

The Committee heard from participants in the online discussion about how a chronic condition can impact on people’s economic activity.i People with Long COVID explained to the Committee that their symptoms flare and wane in an unpredictable way, as well as vary in their severity and impact on the person.ii The Committee also heard that people commonly experience a re-lapse of symptoms long after they were first diagnosed with COVID-19. The unpredictable and long-term nature of these symptoms present numerous challenges for working people or people who are economically inactive due to their health condition but would like to join the labour market.

The Committee was informed that standard workplace procedures, such as sick leave or return-to-work policies, do not provide suitable support for a person with a chronic illness. This is because these policies are usually designed to meet expectations of an average healthy person, rather than someone with a chronic illness. Return-to-work programmes, for example, are usually time-limited, often for up to 12 weeks. Permitted absence periods are also usually time limited.iii One individual with long COVID told the Committee how he had participated in numerous unsuccessful return-to-work programmes, before deciding to take an unpaid career break for 12 months to try and recover his health to enable him to re-join the workforce. This came at significant personal and financial cost.

Participants also recounted their experience of employers failing to meet requests for reasonable adjustments, such as remote working, to support them to stay in employment whilst managing the symptoms of their chronic illness.iv The Committee was also informed that a person’s recurring symptoms can also trigger formal absence management processes or disciplinary procedures, which may otherwise be designed to manage non-health related employment issues. Participants explained that these factors can push people out of the labour market or create barriers for entry, or re-entry, into the workplace. In the case of Long COVID specifically, the Committee heard from the Institute for Fiscal Studies that the condition may be having a bigger impact on people's productivity whilst remaining in employment, rather than forcing them to leave the labour market and become economically inactive.v This is considered in more detail in the Long COVID section below.

Employment law, specifically including matters related to employment and industrial relations, and health and safety, non-devolved job search and support, is a reserved matter under Schedule 5, Head H of the Scotland Act 1998.vi Notwithstanding this, the Minister's portfolio includes responsibility for "just transition, employment and fair work" in light of relevant powers devolved to Scottish Ministers.vii The Minister explained to the Committee that the Scottish Government would be publishing a Fair Work Action Plan,v which for the first time would attempt to address intersectional barriers faced by individuals in the labour market.ix

The Committee notes that chronic illness is a leading reason for economic inactivity in Scotland. The Committee seeks clarification from the Scottish Government on what guidance and support it is providing within its devolved powers to employers to implement fair work employment policies, including sick leave and return-to-work programmes, that are tailored to the needs and experiences of people with chronic illnesses, including Long COVID.

Employability services

The Committee heard that nearly one in four people in the UK who are inactive because of ill health wants to or is seeking work, but they are unable to start, because of the barriers that they experience to entering or re-entering the workplace.i This figure equates to 58,000 people in Scotland.i The Committee visited Airdrie, North Lanarkshire, which experiences some of the highest levels of economic inactivity due to long-term illness in Scotland, to see how employability services are being implemented to support people into the labour market.

The Committee visited Remploy’s office in North Lanarkshire to see how it is using the Scottish Government’s Fair Start Scotland programme funding to deliver employability services. The Committee learned that key features of the programme include its voluntary nature, the personalised and breadth of support provided, as well as the length of support available (between 12-18 months).

The Committee heard from one participant who intended to seek employment in administration and received support from Remploy to gain relevant skills in this area. Through developing close working relationships with Remploy staff, he changed direction and took a stock replenishment and shelf-stacker role working part-time, late-night shifts in a supermarket. This employment opportunity better suited his mental health needs and taking the role has helped build his confidence.

The Committee also visited Routes to Work Ltd to see how it is using the UK Government's Community Renewal Fund to deliver employability services. This fund is designed to enable local communities to pilot imaginative new approaches and programmes, including employment support, to address local challenges. The Committee learned how Routes to Work Ltd has used this funding to establish an engagement hub in Airdrie’s Market Square. The Committee heard that this has been a particularly effective way of reaching the local community when COVID-19 had made it difficult to conduct home visits.

The Committee met with a participant who was made redundant during the pandemic and developed depression. She engaged with the hub during a visit to the town centre, and from there was supported to get back into employment, first through a local supermarket, before regaining the confidence to seek employment in the betting industry where she had previous experience.

The Committee greatly valued the opportunity to hear from service users about their personal circumstances and the support they have received. The Committee noted that many people they spoke with experienced improved mental health or wellbeing once they secured a suitable job and felt supported to remain in work for the longer-term.

The Scottish Government informed the Committee that it is satisfied that its employability programmes are working well.i The cost crisis, however, has put increased pressure on public spending, as highlighted in the Scottish Government’s Emergency Budget Review and proposed Budget for 2023-24. This included a decision to make a £53 million saving by not proceeding with a planned expansion of employability services, which include the Fair Start Scotland programme. In its proposed Budget for 2023-24, the Scottish Government explained that–

The decision to take £53 million as a saving from employability funding was not taken lightly, but in light of the challenging financial situation we sought to make the savings that we consider have the least impact on public services and on individuals during the cost crisis. Over £82 million in total has been made available (£59.433 million through No One Left Behind and £23.5 million through Fair Start Scotland), to ensure employability support remains in place for those who need it, including parents.iv

The Committee notes that for people who are far away from the labour market, wrap-around employability services, like the Fair Start Scotland programme, are essential for supporting people into employment. Good work is being done using this and other available employability funding programmes. The Committee considers that best practice should be shared and implemented across all local authorities. The Committee invites the Scottish Government to consider how it can use the findings from its evaluation of the Fair Start Scotland programme to embed best practice across all local authorities.

Long COVID

The Committee sought to understand the extent to which Long COVID has been contributing to economic inactivity since the start of the pandemic. The Committee spoke with people who shared their experience of trying to remain in work whilst managing their Long COVID symptoms.i In many cases, this was having a significant and lasting impact on people’s wellbeing and livelihoods.

The Committee received mixed responses to its call for views on whether long COVID is having an impact in overall levels of post-pandemic labour market participation. According to the ONS, data suggests that some of the increased economic inactivity experienced since the pandemic began could be due to Long COVID. The ONS also explained that the prevalence of self-reported Long COVID appeared to be higher in Scotland than in England. In July 2022, 3.83% of the private-households population were estimated to be living with self-reported Long COVID of any duration, compared with 2.98% in England.ii Long COVID Scotland and #MEAction Scotland agreed that Long COVID has been a contributing factor to recent economic inactivity.iii When the Committee raised this with the Scottish Government it explained that “our emerging sense is that Covid and Long Covid are not directly driving the increase in inactivity because of ill health, although they could be indirect factors.”iv

Some respondents noted that there is a lot of uncertainty in the available data, which means it may be too early to tell what impact Long COVID is having on the labour market. This is partially due to ongoing uncertainty about how to define Long COVID in Scotland and the UK.iv Many sources of data on the prevalence and impact of Long COVID also rely on self-reported surveys, such as the ONS’ Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey and the Labour Force Survey. Although people may report that they are experiencing the symptoms of Long COVID, many of these symptoms are shared with other conditions, or could be attributed to other factors.iv

The Committee was also informed that patient data, which is another means of determining the prevalence of Long COVID, relies on medical practitioners coding for a Long COVID diagnosis in health records. Patient data may not provide a complete picture of the prevalence of Long COVID because it relies on people engaging with the health service, which not all affected people may do. In situations where someone has engaged with general practice or had a specialist referral, a diagnosis of Long COVID may not take place before other possible underlying causes are investigated, thereby leading to a ‘diagnosis by exclusion’.iv This can mean there may be a delay in the reporting of Long COVID in patient data.

Other respondents, such as Public Health Scotland, Royal Society of Edinburgh, East Ayrshire Council and the Institute for Fiscal Studies noted that the impact of Long COVID is being felt unequally, with sufferers more likely to have a pre-existing condition, be female, or middle aged and economically disadvantaged.viii The Committee heard that the Chief Scientist Office is funding a longitudinal study that is trying to understand the prevalence of Long COVID in Scotland, as well as how to predict who is most at risk of developing the condition.iv

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies has found that Long COVID may be driving an increase in the number of people who remain employed but are on sick-leave or who are experiencing economic inactivity in the short-term.viii The study estimates that one in ten people who develop Long COVID stop working, with sufferers generally opting to take sick leave (rather than losing their jobs altogether). The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that for Long COVID sufferers the hours worked on average reduce by about 2.5 hours per week and earnings by £65 per month (6%), or £1,100 per person who drops out of work. For the UK as a whole, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that while the prevalence and severity of COVID remain at current levels, the aggregate impact is equivalent to 110,000 workers being off sick. The Committee heard that in practice, this research suggests that Long COVID may be impacting on productivity, rather than headline labour market participation and rates of economic inactivity.

Participants who spoke to the Committee at its informal session on 20 November explained that because Long COVID is not recognised as a disability under the UK Equality Act 2010, people who have Long COVID cannot benefit from its protections, such as making a claim for an industrial injuries disablement benefit.xi The Committee raised this evidence with the Scottish Government who explained that it has decided that Long COVID should not be recognised as a disability.iv The Scottish Government noted that not everyone who experiences Long COVID will be disabled by the condition and that a person’s disablement should be assessed “on the basis of function, as opposed to diagnosis”.iv

The Committee is keen to better understand the public health support available to people experiencing Long COVID and has therefore decided to consider this further in a separate inquiry to be launched in 2023.

Disabled people's experience of economic inactivity

The Committee also considered the extent to which disabled people have been impacted by economic inactivity. The Committee heard that disabled people are more likely to be economically inactive than non-disabled people. In 2021, more than 380,000 disabled people aged 16 to 64 were economically inactive in Scotland.i Although rates of economic inactivity are much higher for disabled people than non-disabled people, the Committee heard that this does not reflect a lesser willingness to work.i In 2019, approximately one quarter of economically inactive disabled people wanted to work. This is a higher proportion than the number of inactive non-disabled people who wanted to work, which was less than one fifth.i

The Committee heard from Inclusion Scotland that there are a wide range of factors that have contributed to disabled people’s economic inactivity in Scotland pre-pandemic, during the initial shock and in the current recovery phase of the pandemic. These include–

…poor health outcomes in general, a mental health crisis and poorly constructed and under-funded mental health services, poverty and health inequality, the persistence of the disability employment gap in Scotland (and the barriers that disabled people experience finding and keeping employment which can lead them to leaving work and/or not looking for work), unfair treatment at work, the impact of Long COVID on the labour market and the workplace issues experienced by disabled people at high risk of the virus.iv

Inclusion Scotland also explained that getting and keeping reasonable adjustments in place is an ongoing issue for disabled workers that predated the pandemic. More than half of disabled workers (55 per cent who identified reasonable adjustments) were not getting all the reasonable adjustments they needed prior to the pandemic.v This is because they had not asked for reasonable adjustments even though they required them, or when they did request reasonable adjustments, they did not receive all or any of the adjustments requested. Inclusion Scotland explained that these issues continued to be prevalent during the pandemic despite a wider shift in more employers embracing flexible working opportunities.vi

Inclusion Scotland also called for shift in the focus of employability support for disabled people. Rather than assuming disabled people require upskilling or other support to join the labour market, Inclusion Scotland considers that increased focus should be put on supporting employers to make their workplaces inclusive and accessible.i In this regard, Inclusion Scotland observed that many people with chronic illnesses had requested reasonable adjustments to work from home prior to the pandemic, but it was not until the pandemic occurred that these possibilities were fully explored by some employers.i Public Health Scotland noted some support is available to small and medium sized enterprises to access to occupational health services through National Services Scotland, but more needs to be done to improve access to in-work support.i

The Scottish Government has a policy target to at least halve the disability employment gap by 2038 to 18.7 percentage points from the 2016 baseline of 37.4 percentage points.x The Scottish Government explained to the Committee that—

The latest figures indicate that, in the five years between 2016 and 2021, the disability employment gap in Scotland has reduced by 6.2 percentage points, and it currently stands at 31.2 per cent. That suggests that we are currently on track to achieve our ambition to halve the disability employment gap to 18 percentage points by 2038.i

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's progress on reducing the disability employment gap in line with its existing 2038 target. The Committee notes that the provision of reasonable adjustments appears to be a significant and ongoing barrier to eradicating the disability employment gap. The Committee seeks clarification from the Scottish Government on what steps it is taking to monitor and support the provision of reasonable adjustments by employers.

Data

The Committee was interested to consider whether health and economic data can be linked to better understand how people's health affects their economic activity. Professor Fothergill noted that two main data sets are used to analyse health reasons for economic inactivity: the Labour Force Survey (including the Annual Population Survey) and the benefits data held by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).i

Professor Fothergill noted that the sample size for the Labour Force Survey is small, although the Scottish Government funds a boost for Scotland to increase the available data from approximately 4,000 households to 13,000 households for the latest time periods.i The ONS explained that the Labour Force Survey is moving from face-to-face interviews to online surveys, which will produce an initial sample that is approximately 60-80 per cent bigger than the current sample. This will be rolled out towards the end of 2023 and will enable the ONS to produce more granular data for Scotland.i

Professor Fothergill also explained that the benefits data that can be sourced from the DWP includes the number of people on employment and support allowance or universal credit. This data can be produced at national and local authority level, broken down by age and gender.i The Institute for Employment Studies agreed that administrative data, such as benefits data, are useful sources of information, but suggested that DWP data could be better disaggregated to show how universal credit data compares with the legacy benefits that it replaced.i In particular, the Institute for Employment Studies considered this data would be improved if it could show how long people are spending out of work, how many people are flowing out of and back into work, and how people move between economic inactivity (when they are not looking for work), employment and unemployment.i

On wider economic activity data, the Institute for Employment Studies also noted that HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) data on pay as you earn and employee numbers has been affected by a significant shift from self-employment to employee jobs, which makes it difficult to disaggregate the underlying true picture of people working under an employment contract (‘employee employment’).i The ONS explained that it is working with HMRC to expand the available data, which provides data down to the local authority level and work is underway on cross tabulations by country and region of the UK to make data on each country by age and by industry available.i

Professor Sir Aziz Sheikh, Professor of Primary Care Research and Development and Dean of Data for The University of Edinburgh, informed the Committee that significant advancements were made during the pandemic to use data to inform policy decision-making in real time. This data advancement was primarily used to enable policy makers to understand what impact the vaccination programme was having on public health. In Sir Aziz’s view, linking health data with economic data would be possible but would require government “…to instruct the country to move in that direction”.i

Sir Aziz explained that Scotland has “the best [public health] data sources in the world”.i In his view, there would be value in moving towards a “whole-system intelligence for NHS Scotland” to improve services and to “bend the cost curve”. Sir Aziz noted the example of mental health data and explained that Scotland has very granular GP data on 5.4 million people in Scotland. In his view, with the appropriate “instruction, resources and permissions” weekly data could be produced on what mental health looks like in Scotland within a couple of weeks.i

The Scottish Government agreed that there are opportunities to make better use of health data and that this would form a significant part of the mental health strategy that will be published in Spring 2023.i In relation to linking health and economic data, the Scottish Government noted that some of the sources of economic activity data are collected at a UK level and can be challenging to use due to very small subsamples” for Scottish data in what is collected.

The Committee sought information on the data being used by the Scottish Government to measure its progress towards realising a wellbeing economy and how this relates to long-term illness as a driver of economic inactivity. On 24 June 2022, the Scottish Government published a wellbeing economy monitor, which includes a range of indicators to provide a baseline for assessing its progress towards the development of a wellbeing economy in Scotland.xiii The monitor contains 14 indicators grouped into four categories, referred to as “capitals” (natural capital; human capital; social capital; and produced and financial capital). Economic inactivity due to (short-term or long-term) illness is not included in the indicators. The Scottish Government explained to the Committee that it wants to see a healthy working population and that considerations about levels of economic inactivity are “taken into account in the round”.i

The Committee notes the evidence from Professor Sir Aziz Sheikh that the pandemic has shown that Scotland has the potential to be a world-leader in using health data to inform public policymaking, including policies aimed at tackling economic inactivity and its underlying causes. The Committee heard in evidence that the biggest barriers to realising this ambition appear to be a lack of "instruction, resources and permissions". The Committee seeks clarification from the Scottish Government on its response to this evidence, including what amount, it is investing in the advances made in health data analysis during the pandemic in wider policy areas, particularly initiatives to support the preventative health agenda and open access public health data.

The Committee also considers that there is an opportunity for greater cross-portfolio working between the health and economy portfolios to reduce economic inactivity. The Committee welcomes the publication of the wellbeing economy monitor, which aims to provide a baseline to measure progress towards a wellbeing economy. The Committee invites the Scottish Government to consider including measures of health-rated reasons for economic inactivity as additional indicators in the monitor.

Early retirement

The Committee sought to understand the extent to which early retirement is driving economic inactivity in Scotland. The ONS advised that there is limited available evidence on early retirement in Scotland. Its Over-50s Lifestyle Study samples attitudes from adults aged 50 and over in Great Britain to gather information on participants’ motivations for leaving work and whether they intend to return. The latest study found that in the second wave of the pandemic (sampled between 10 and 29 August 2022)—

one-quarter (25%) of adults said they left work for retirement, slightly lower than wave 1 (28%)

slightly more adults wanted a change in lifestyle in wave 2 (18%) than those in wave 1 (14%)

a much higher proportion of adults aged 50 to 59 years said they would consider returning to work in wave 2 (72%) than in wave 1 (58%)

in wave 2, a higher proportion of those aged 50 to 59 years would consider returning to work for the money (65%) than in wave 1 (56%)

for all adults aged 50-65 regardless of employment status, fewer adults reported to be very or somewhat worried about the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in wave 2 (46%) than in wave 1 (67%), while non-working adults reported more increased worries about the cost of living in wave 2 (55%) than in wave 1 (45%).i

The ONS’ Annual Population Survey provides information on local labour markets in the UK and includes data from the Labour Force Survey with a Scottish Government-funded boost to the Labour Force Survey sample size.i This shows that early retirement was on a downward trend in the 10 years prior to the pandemic and saw a modest increase in the period between 2019-2020 and 2021-22. Since then, the figures appear to be falling again and are less than they were 10 years ago, as illustrated in Figure 4 below–

Figure 4  ONS Annual Population Surveyiii

ONS Annual Population Surveyiii

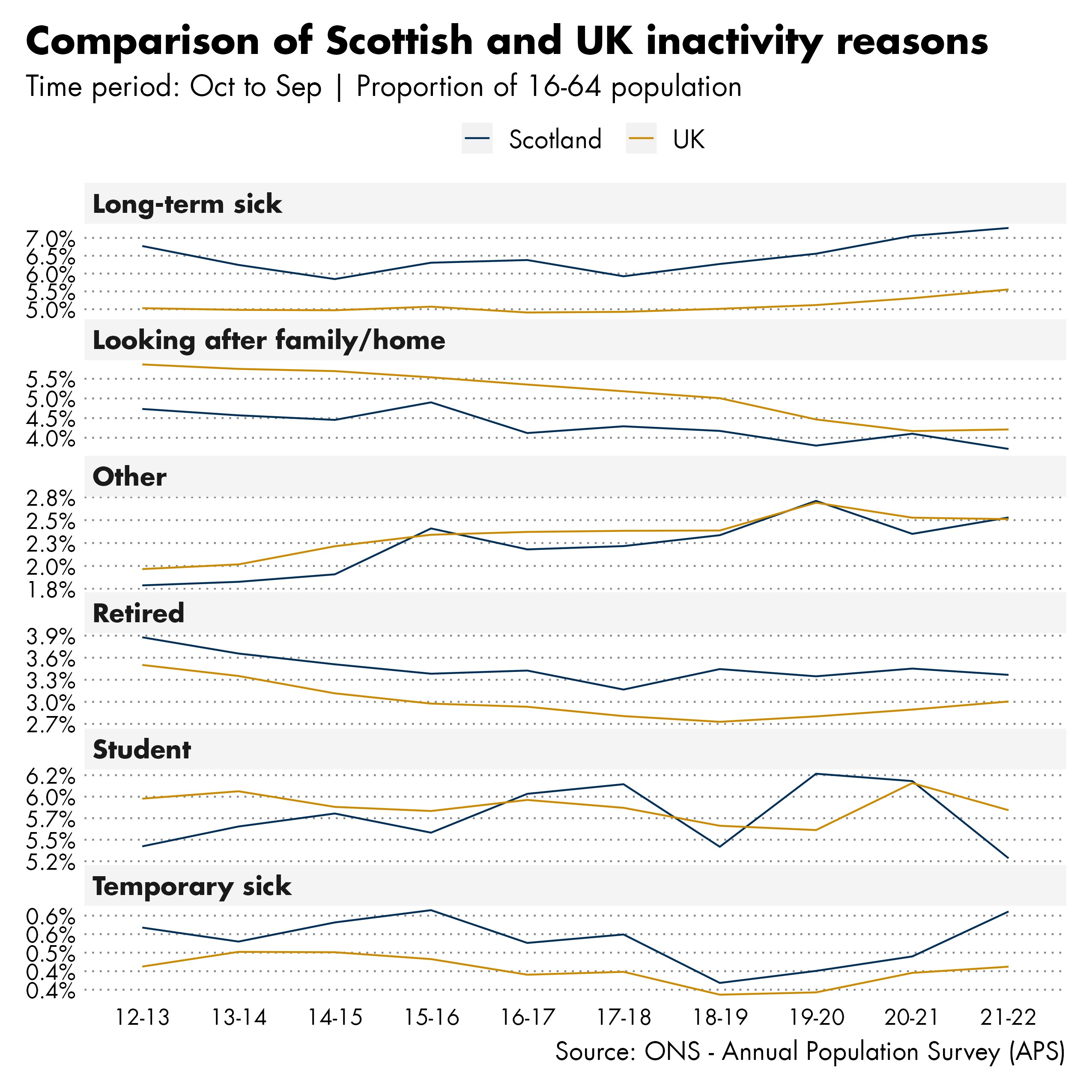

The Committee also considered whether there were different drivers in economic inactivity for men and women. The latest available data from the Annual Population Survey is shown in Figure 5 below–

Figure 5  Annual Population Surveyiii

Annual Population Surveyiii

The Committee could not identify conclusive evidence behind men’s inactivity rates and the reasons why there was an increase in men taking early retirement compared to women. Some witnesses suggested that men have on average greater financial security than women and therefore may be more able to take early retirement.v The Committee considered whether menopause was having an impact on women’s labour market participation but could not identify conclusive evidence on this issue. Close the Gap noted that there is a need for greater intersectional data to provide an evidence base on women’s experience of menopause.v

The Committee held an engagement session to understand the reasons why people have taken early retirement since the pandemic began. The Committee spoke with people from a range of sectors and a recruitment specialist. The Committee heard that stress, burnout, inability to continue physically demanding duties, caring responsibilities, lack of flexible working and training opportunities had been contributing factors in people’s decisions to take early retirement.vii The people who spoke to the Committee felt they would not be persuaded to re-enter the workplace, despite the increased cost of living since the pandemic.viii

The Committee heard that, although policy interventions are not likely to have impact once someone has retired, a greater focus could be placed on retaining older workers in the labour market. For example, numerous witnesses explained that older workers are attracted to flexible working opportunities, such as part-time positions.ix Although the pandemic has highlighted new ways of working, presenteeism and a traditional attitude to the workplace (such as 9.00AM-5.00PM working days, full-time working hours etc.) remains a persistent feature of UK work culture.viii Indeed, the Committee heard that the flexible jobs index that was published in Scotland last year showed that only just over a quarter—27 per cent—of jobs were advertised as being flexible. Close the Gap suggested that the pandemic has not resulted in a workplace revolution that is sometimes presented.xi

The Committee also heard from a recruitment specialist who noted that high employment figures mean that employers will increasingly find they need to make their job opportunities attractive to prospective and existing employees in a competitive market. She explained that smaller businesses, more so than other employers, may need additional support to implement flexible working or other ways of making their roles attractive to prospective employees.xii The Committee heard from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development that employer investment in skills and development has declined in recent years and employers need to consider reinstating these opportunities as part of their recruitment and retention strategies, particularly for older workers.v

The Scottish Government told the Committee that “Our emerging sense is that early retirement is not on the same scale as long-term sickness as a driver of increasing inactivity”.v The Scottish Government also noted that inactivity amongst the 50–64-year-olds appears to be driven by sickness and caring for others, rather than by retirement.v

The Committee noted that the Scottish Government's National Strategy for Economic Transformation includes a commitment to establish a Centre for Workplace Transformation by 2022.xvi This proposal came from the Scottish Government's Advisory Group on Economic Recovery, which recommended that it be established with the aim of “…improving business performance, productivity, innovation, Fair Work, workforce resilience and worker wellbeing.” The Advisory Group recommended that the Centre be established by the end of 2020 with a fully costed plan.xvii

The Committee asked the Scottish Government for details on the progress being made toward establishing the Centre for Workplace Transformation. The Scottish Government explained it remains committed to establishing the Centre but that it has many “…considerations to take on board in the current climate.”v

The Committee notes that flexible working practices are a priority for many older workers, which would incentivise them to stay in the labour market for longer. The Committee considers that the Scottish Government's proposal to establish a Centre for Workplace Transformation is a laudable policy ambition to embed some of the learning gained from the pandemic on flexible working. Notwithstanding current inflationary pressures on the Scottish budget, the Committee was disappointed to learn that this policy commitment has not been delivered within the 2022 target. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to clarify its plans for delivering this policy ambition, including any costings and delivery options that it has explored for implementing the policy commitment.

Annexe A

Extracts from the minutes of the COVID-19 Recovery Committee, public engagement sessions and associated written and supplementary evidence

23rd Meeting, Thursday 3 November 2022

1. Road to recovery: impact of the pandemic on the Scottish labour market: The Committee took evidence from—

Dr Hannah Randolph, Economic and Policy Analyst, Fraser of Allander Institute;

Professor Steve Fothergill, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, National Director, Industrial Communities Alliance;

Tony Wilson, Director, Institute for Employment Studies;

David Freeman, Head of Labour Market and Households, Office for National Statistics;

Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation.

2. Consideration of evidence (In Private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

Written evidence:

24th Meeting, Thursday 10 November 2022

1. Road to recovery: impact of the pandemic on the Scottish labour market: The Committee took evidence from—

Susie Fitton, Policy Manager, Inclusion Scotland

Pamela Smith, Head of Economy and Poverty, Public Health Scotland

Professor Sir Aziz Sheikh, Professor of Primary Care Research and Development, Director Usher Institute and Dean of Data, University of Edinburgh

Professor Gerry McCartney, Professor of Wellbeing Economy, University of Glasgow

and then from—

Tom Waters, Senior Research Economist, Institute for Fiscal Studies

Tom Wernham, Research Economist, Institute for Fiscal Studies

Philip Whyte, Director, IPPR Scotland

2. Consideration of evidence (Private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

Written evidence:

25th Meeting, Thursday 17 November 2022

Apologies received from: Murdo Fraser (Deputy Convener).

1. Road to recovery: impact of the pandemic on the Scottish labour market: The Committee took evidence from—

Marek Zemanik, Senior Policy Advisor, Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development;

Bee Boileau, Research Economist and Jonathan Cribb, Associate Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies;

David Fairs, Executive Director of Regulatory Policy, Analysis and Advice, The Pensions Regulator;

Dr Liz Cameron CBE, Director and Chief Executive, Scottish Chambers of Commerce;

and then from—

Anna Ritchie Allan, Executive Director, Close the Gap;

Chris Brodie, Director of Regional Skills Planning and Sector Development, Skills Development Scotland;

Anjum Klair, Policy Officer and Jack Jones, Policy Officer, Trades Union Congress .

2. Consideration of evidence (In Private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

Written evidence:

27th Meeting, Thursday 8 December 2022

1. Road to recovery: impact of the pandemic on the Scottish labour market: The Committee took evidence from—

Richard Lochhead, Minister for Just Transition, Employment and Fair Work,

Lewis Hedge, Deputy Director, Fair Work and Labour Market Strategy and

Dr Alastair Cook, Principal Medical Officer, Mental Health Division, Scottish Government.

2. Consideration of evidence (In Private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

2nd Meeting, Thursday 26 January 2023

1. Road to recovery: impact of the pandemic on the Scottish labour market (In Private): The Committee considered a draft report. Various changes were agreed to, and the report was agreed for publication.

Visit to Airdrie: Thursday, 28 November 2022

Written evidence

Summary of written responses

Scottish Parliament Information Centre. Summary of written responses, 26 October 2022, CVDR/S6/22/23/2.