Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee

Putting Artists In The Picture: A Sustainable Arts Funding System For Scotland

Executive Summary

The Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee launched this inquiry at what is a pivotal moment for arts funding policy in Scotland. There is now, for the first time, a national outcome on culture within the Scottish Government's National Performance Framework. This should raise our ambition for the arts and culture to be embedded in all aspects of government policy. Creative Scotland will shortly announce the outcome of its funding strategy review and the Scottish Government’s culture strategy is expected imminently. Scotland’s arts funding system is facing ongoing challenges and uncertainty arising from fluctuations in National Lottery income, wider pressures on public finances and a lack of clarity about the direction of the UK’s future relationship with the European Union. In this landscape, artists face increasing competition for funding in what many see as a bureaucratic system that does not adequately support them to build sustainable careers and artistic ventures.

This report sets out recommendations that focus on putting artists at the centre of Scotland’s arts funding system. Public funding of the arts will only be sustainable if artists are paid a fair wage and the Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government and Creative Scotland to take urgent, robust action on this issue. The Committee recommends in this regard that the Scottish Government develop a new indicator within the National Performance Framework to monitor the number of self-employed artists and cultural freelancers who are paid a fair wage and that Creative Scotland should take steps to ensure greater transparency in the amount of funding it awards that goes directly to artists producing artistic work, in order to raise the profile of this important issue within government. The Committee also recommends that artists and cultural freelancers should be included in the ongoing feasibility studies for a basic citizens’ income funded by the Scottish Government.

The Committee has also made recommendations for Creative Scotland to change the way it allocates funds by putting artists at the centre of its approach. The measures suggested by the Committee include incorporating peer review into its application processes; creating a tiered application process to reduce the burden on applicants who are unlikely to progress to later stages of the process; and introducing funding programmes, such as bursaries and stipends, aimed at supporting artists and arts organisations at different stages of their development. The Committee also makes a recommendation for the Scottish Funding Council, in conjunction with relevant partners, to ensure that artists in further and higher education are supported to gain the necessary business skills to support them to build a career as an artist.

The Committee’s inquiry has highlighted that a sustainable arts funding system is one where all government portfolios are strategically aligned to fund the arts in a way that supports and delivers national outcomes. The Committee therefore recommends that the Scottish Government sets out its approach to funding its forthcoming culture strategy, including how this will be delivered across portfolios. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give serious consideration to setting a baseline target for national arts funding, on a cross-portfolio basis, above 1% of its overall budget.

The Committee’s inquiry has also highlighted the complexity of public funding for the arts and the difficulty in accessing data to measure the impact of investment. The Committee has also highlighted the need to improve data on local authority culture spending. The Committee has therefore recommended that the Scottish Government establish an independent national cultural observatory in consultation with local government, relevant agencies and stakeholders.

This inquiry has also highlighted the need for the Scottish Government to plan for known challenges to arts funding in the medium-term that threaten artists’ ability to produce work and plan for the future, including Brexit and fluctuations in Creative Scotland’s National Lottery income. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should set out its plans for protecting Creative Scotland's funding in the long-term before its existing commitments to protect Creative Scotland's budget expire. The Committee has also recommended continuing Scotland's participation in the Creative Europe Programme. The Committee’s inquiry has highlighted possible avenues of additional funding that could be leveraged to address these challenges, such as a ‘percentage for the arts’ capital investment scheme.

A sustainable arts funding system is also one where the Scottish Government and local authorities work in partnership to support artists in all parts of Scotland. The Committee's inquiry has highlighted why the relationship between local and national government must therefore be re-set. The Committee has recommended that the Scottish Government work with local authorities to create a new policy framework to support the arts. The Committee recommends that the new framework should include a requirement for local authorities to plan for culture and to take account of local and national priorities in doing so. The Committee’s view is that the Scottish Government should consider using new legislation, such an ‘Arts Act’, to establish the new policy framework and to work with COSLA and local authorities in developing it. Other measures that the Scottish Government should take in resetting this relationship, include working with COSLA to jointly develop guidance for implementing the forthcoming culture strategy; and creating a refreshed approach for maintaining cultural venues across all parts of Scotland.

A sustainable arts funding system must also be one for all of Scotland. The geographical distribution of national arts funding therefore needs to be improved as a matter of priority. In this regard, the Committee recommends that Creative Scotland take action to ensure that its new funding approach improves on the current geographic spread of regular funded organisations. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government work with Creative Scotland to re-establish a programme of funding for regionally-based arts officers in local authority areas where Creative Scotland's investment is significantly below the Scottish average.

Recommendations

Investment in Scotland's Artists

The Committee recommends that a new indicator is developed to measure the extent to which self-employed artists and cultural freelancers working in the arts and wider creative sector are paid a fair wage. [para 174]

The Committee notes the steps taken by Creative Scotland to encourage the organisations and projects that it funds to adopt fair pay practices. The Committee recommends that a more robust approach is required from Creative Scotland and invites it to take action to address this issue. [para 175]

The Committee recommends that Creative Scotland measures funding that is allocated to artists who are producing artistic work as a proportion of the total amount of funding for each grant that it awards. [para 176]

The Committee recommends that Creative Scotland consider ways that the funding application process for its grants could be tiered to focus the early stages of the funding process on artistic merit and reduce the burden on applicants who are unlikely to progress to later stages of the application process. [para 188]

The Committee recommends that Creative Scotland incorporate peer review into its application processes drawing on the experience from comparative countries and funding models highlighted in this report to ensure that diversity and fairness is built into the peer assessment process. [para 189]

The Committee recommends that there should be no circumstances in which individual artists should be competing against network organisations for funding from Creative Scotland. [para 190]

The Committee recommends that Creative Scotland should redesign its overall funding framework in a way that recognises and supports artists and arts organisations at different stages of their professional development. The Committee notes, in this regard, that this approach is used in other European countries, including France and Ireland and invites Creative Scotland to consider how comparative approaches, such as bursaries and 'stipends', could be used in Scotland. [para 199]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Funding Council in conjunction with relevant partners ensures that the outcome agreements it has with further and higher education institutes with regard to employability and career support is being applied to programmes relevant to the arts. [para 200]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government take steps to ensure that artists and cultural freelancers are included in the range of participants in the ongoing feasibility studies into a basic citizens income. [para 204]

The Current Funding Landscape

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government articulate its spending plan for the forthcoming culture strategy, including what funding will be earmarked for the arts from other portfolios to deliver the national outcome on culture in a cross-cutting way. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give serious consideration to the culture strategy being supported, on a cross-portfolio basis, by a baseline target for national arts funding above 1% of the Scottish Government’s overall budget. [para 24]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should articulate a long-term strategy for protecting Creative Scotland’s budget from fluctuations in National Lottery income and to do so before its existing commitment in the short-term to protecting Creative Scotland’s budget expires. [para 43]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should seek to maintain Scotland’s participation in the Creative Europe programme after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give consideration to arts funding as part of its consultation on the replacement of European Structural Funds after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. [para 52]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government, its agencies and local authorities need to reset their relationship in relation to arts and culture policy, including approaches to funding. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government adopt a proactive approach to re-engaging with all local authorities to discuss shared priorities for spending and to share best practice in leveraging investment in the arts. [para 70]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government establish an independent national cultural observatory in consultation with local government, relevant agencies and stakeholders. The purpose of the observatory should be to create and manage an open-source national data resource that will draw together existing information collated by all levels of government and relevant agencies to measure the spread and impact of the public funding of the arts across Scotland. [para 77]

The Committee considers the data on local authority cultural expenditure to be inadequate as it may currently encompass culture, tourism, heritage and sport expenditure. The Committee also notes that local authorities diverge widely in their approach to cultural expenditure. The Committee recommends that culture spend is disaggregated and provided separately. [para 78]

Re-setting Local and National Policy alignment

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should work in partnership with COSLA to create a new intergovernmental policy framework between local and national government to support the arts as part of its forthcoming culture strategy. The Committee recommends that the new framework should include a requirement for local authorities to plan for culture and to take account of local and national priorities in doing so. [para 95]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government consider introducing legislation, such an ‘Arts Act’, to create the new policy framework and to work with COSLA and local authorities in creating it. If the Scottish Government considers legislation is not required to achieve this aim, the Committee invites the Scottish Government to explain why it holds this view in its response to the Committee’s inquiry report. [para 96]

The Committee recommends that the forthcoming culture strategy should be underpinned by guidance for local authorities on its implementation, which should be developed jointly with COSLA. [para 100]

The Committee notes that city region deals vary in their approach to culture and recommends that this be revisited where possible. [para 107]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government work with Creative Scotland to re-establish a programme of funding for regionally-based arts officers where Creative Scotland's funding is significantly below the Scottish average in order to stimulate funding where there are relatively few applications at present, in order to support the arts in a sustainable way and to maximise return on public funding investment. [para 122]

The Committee commends the success of the Place Programme and recommends that Creative Scotland should articulate to the Scottish Government and the Committee what measures are needed to deliver it with more local authorities and to strengthen its implementation in a way that embeds the benefits of investment for the long term. [para 123]

The Committee considers it unacceptable that the regular funding round of 2018 did not improve the geographic distribution of regular funded organisations. The Committee recommends that Creative Scotland take action to ensure that its new funding approach improves on the current geographic spread of regular funded organisations. [para 124]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government articulate in its delivery plan for the forthcoming culture strategy how it will create and sustain momentum for its policy implementation in a cross-cutting way bringing onboard local authorities and relevant agencies, including addressing barriers to accessing culture such as transport provision and affordability. [para 138]

The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government articulate its funding strategy for delivering the national outcome on culture across wider portfolios, particularly in priority policy areas, such as education and health. [para 139]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government make its existing commitment to “ensure every school pupil in Scotland is offered a year of free music tuition by the time they leave primary school” an indicator for the national outcome on culture within the National Performance Framework. [para 140]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government work with relevant partners to create a refreshed approach for maintaining cultural venues across all parts of Scotland in the forthcoming culture strategy, supported by a clear funding approach. This could include artists that have developed successful approaches to maintaining commercial and non-commercial cultural venues, social enterprises, COSLA and individual local authorities. [para 150]

The Committee considers that the current approach to funding institutions of national significance (outwith the National Performing Companies and Collections) through the regular funding network is not sustainable. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should consider articulating a new, strategic approach to funding these institutions, by first identifying which institutions it considers should be afforded this status, such as a national youth company, and secondly to identify how they can be funded in a sustainable way. [para 155]

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government investigate how a percentage for the arts policy could be established in Scotland to create additional investment in arts and culture and to embed it in planning for Scotland’s creative future. This could be included in a future 'Arts Act'. [para 161]

Introduction

This report details the findings of the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee’s (“the Committee”) inquiry into arts funding. The Committee first considered issues relevant to this inquiry when it scrutinised Creative Scotland’s handling of the Regular Funding 2018-21 round in 2018. Since then, the Scottish Government has formally consulted on a draft culture strategy and Creative Scotland has launched ongoing reviews into how it operates as an organisation and how it distributes funds. The Committee therefore decided to build on its earlier work by launching an inquiry into the funding of the arts more broadly at what it considers to be a pivotal moment.

The Committee published a call for evidence on 15 March 2019, which invited respondents to reflect on two overarching themes:

What would a sustainable model of arts funding look like; and

How should that funding be made available to artists?

The scope of the call for evidence was limited to the artforms supported by Creative Scotland, excluding television, film and gaming. The Committee considered the Scottish screen sector in detail in its inquiry earlier in this session of parliament, which is why it has not been considered in this report. The scope of this inquiry has also focused on the support available for artforms and not the ‘creative industries’, although the Committee recognises that the arts and creative industries often overlap in a funding and wider context.

The Committee received 69 responses from a range of individual artists and organisations, which were published on its website. The call for evidence also invited respondents to highlight international examples of best practice and the Committee commissioned Drew Wylie Projects Ltd to conduct international comparative research to inform this aspect of the inquiry. The research has been published on the Committee’s webpage and the Committee is grateful to Drew Wylie Projects Ltd for its work in supporting the Committee’s inquiry.

The issues highlighted in written evidence and the Committee’s comparative research were scrutinised in detail over 7 evidence sessions. The Committee also undertook fact-finding visits to Ayr and Dunfermline where it spoke with artists at different stages of their careers, local authority representatives and people otherwise working in and with the arts to deepen its understanding of arts funding in Scotland. The Committee is grateful to Ayrshire College and the Fire Station Creative in Dunfermline who hosted these visits.

The Committee would like to thank everyone who participated in this inquiry, particularly those who are directly involved in producing artistic work. This report draws extensively on the evidence we have taken from Scotland’s artists and arts organisations and seeks to identify a means of establishing a sustainable model of arts funding. Scotland is a creative country with huge potential to build on artistic excellence but to also improve the lives of its citizens through support for the arts and culture. The Committee presents its recommendations to the Scottish Government in this report, which highlight key measures for the Scottish Government to take forward to ensure Scotland’s provision of the arts and support for artistic excellence is supported in a sustainable way.

Part 1: The Current Funding Landscape

The Committee launched this inquiry with the aim of investigating how Scotland could strengthen the funding of the arts to make it sustainable for the long term. This section considers the sources of public funding at a national and local level, including additional sources of funding from the National Lottery and the European Union that are administered by public bodies in Scotland. It highlights some of the challenges that the Scottish Government will need to address in order to deliver a sustainable funding model and makes recommendations to the Scottish Government, and other public bodies, for how this could be achieved.

National Funding

Overview

The Scottish Government launched the current National Performance Framework in June 2018, which included a new national outcome on culture.i The National Performance Framework is intended to help focus the Scottish Government’s activities and spending on outcomes. In this regard, the Scottish Government provides annual funding to support the work of public bodies that are responsible for preserving and promoting the arts and culture in Scotland.ii In addition, the Scottish Government currently funds a number of initiatives that are administered on its behalf, such as the Expo Fund, the Youth Music Initiative, the Cashback for Creativity Fund and the International Creative Ambition Programme. The Scottish Government also currently provides funding to the youth orchestra charity Sistema Scotland.

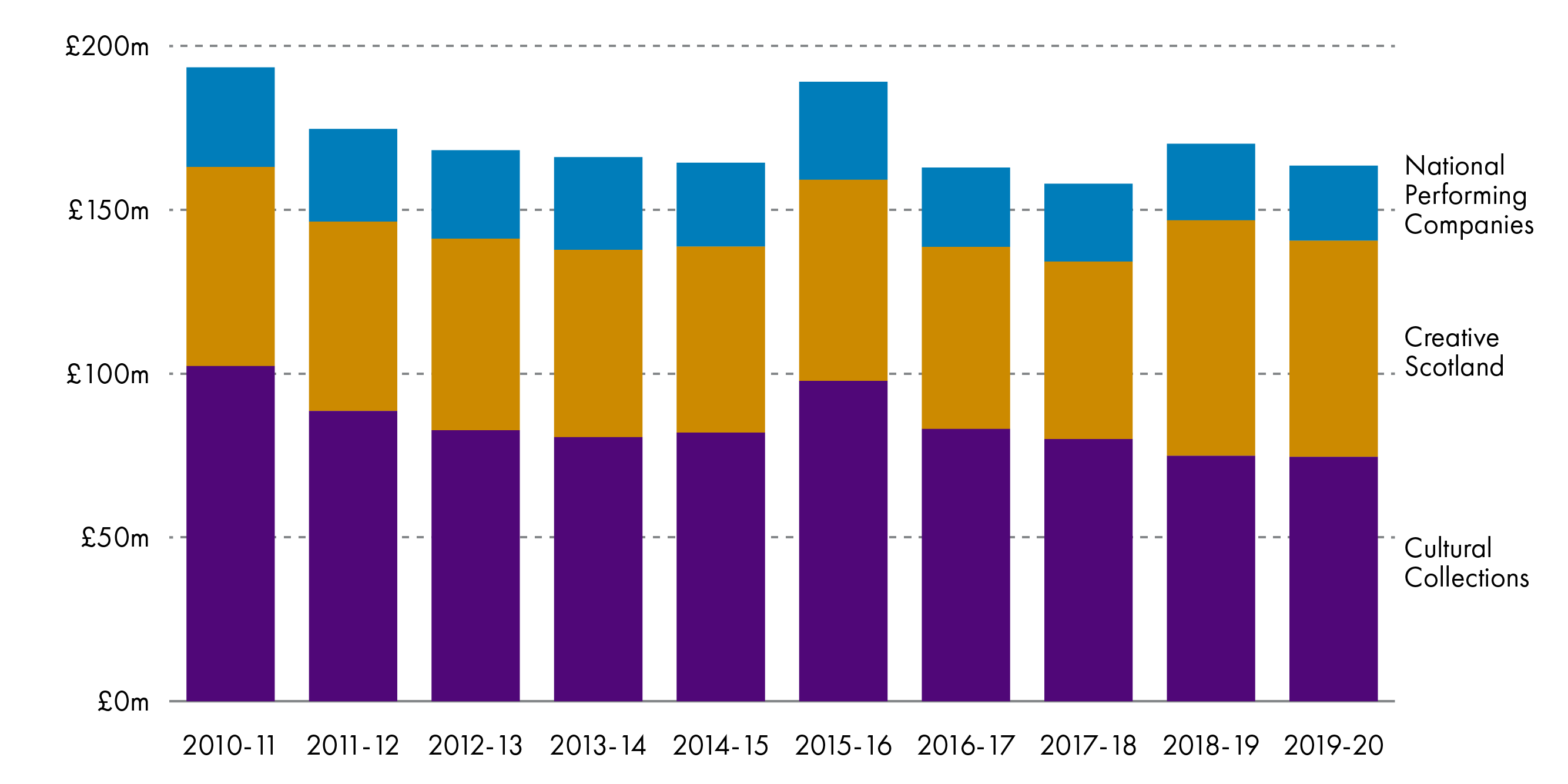

The Committee considered budget lines relevant to the funding of the arts in the Scottish Government’s budget since 2010-11. Figure 1 below shows an overview of the three main strands of Scottish Government funding for arts-related activities, including the National Performing Companies, Creative Scotland and the Cultural Collections. All real terms figures are calculated using HM Treasury deflators.

Figure 1: Scottish Government Creative Scotland, Cultural Collections and National Performing Companies Budget Lines (Level 3), 2010-11 to 2019-20, real terms (2019-20 prices)  Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

This illustrates that the amount of funding allocated to arts-related activities is relatively small in terms of the Scottish Government’s overall budget (not reaching more than £200 million in the relevant period). It also highlights that for such a relatively small amount of funding, the budget in this portfolio is distributed via a considerably complex matrix of public bodies who use it to support a wide variety of artforms and activities. The relevant budget lines for the three main funding streams (Creative Scotland; National Performing Companies; and Cultural Collections) are considered in turn below.

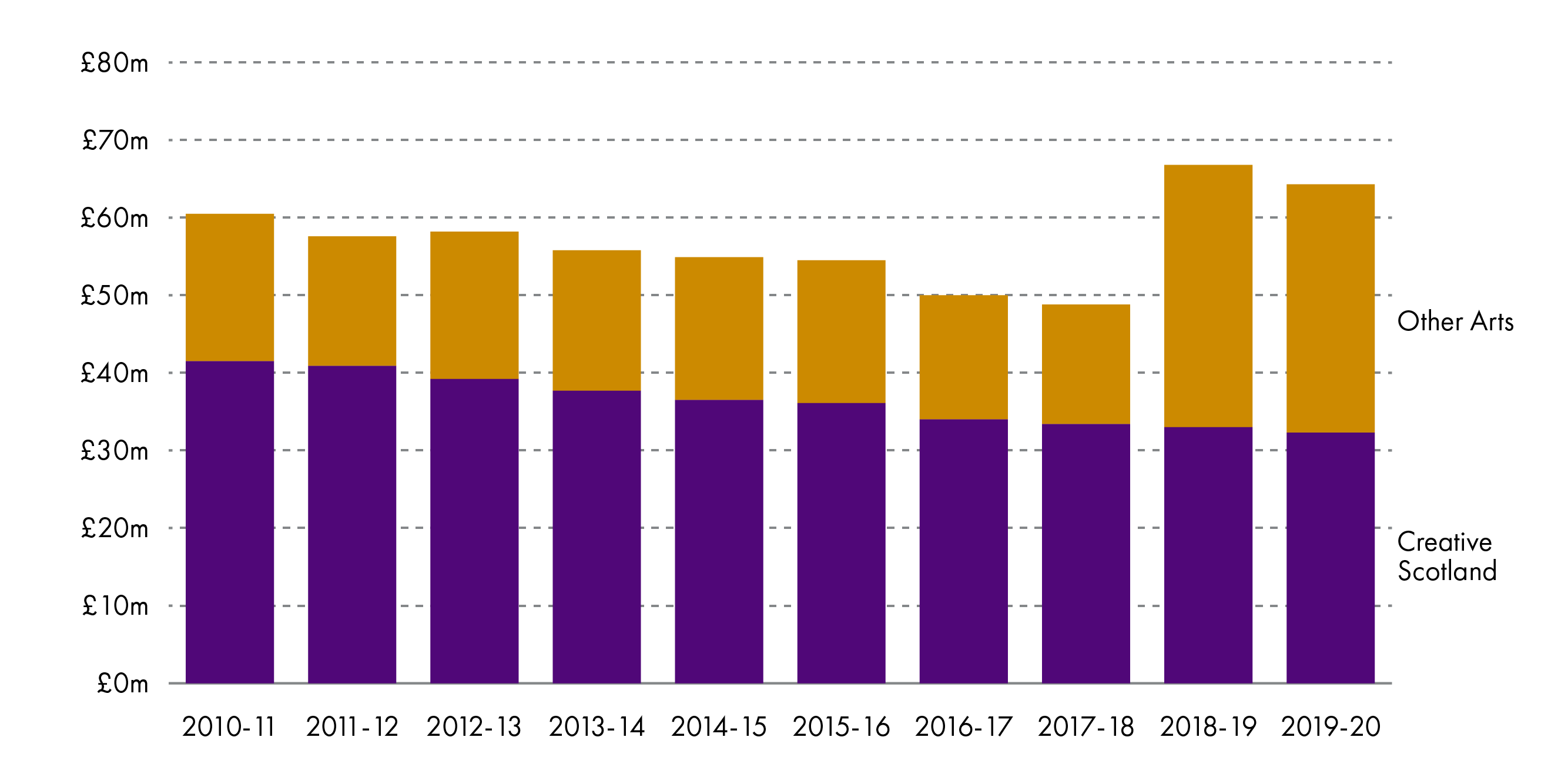

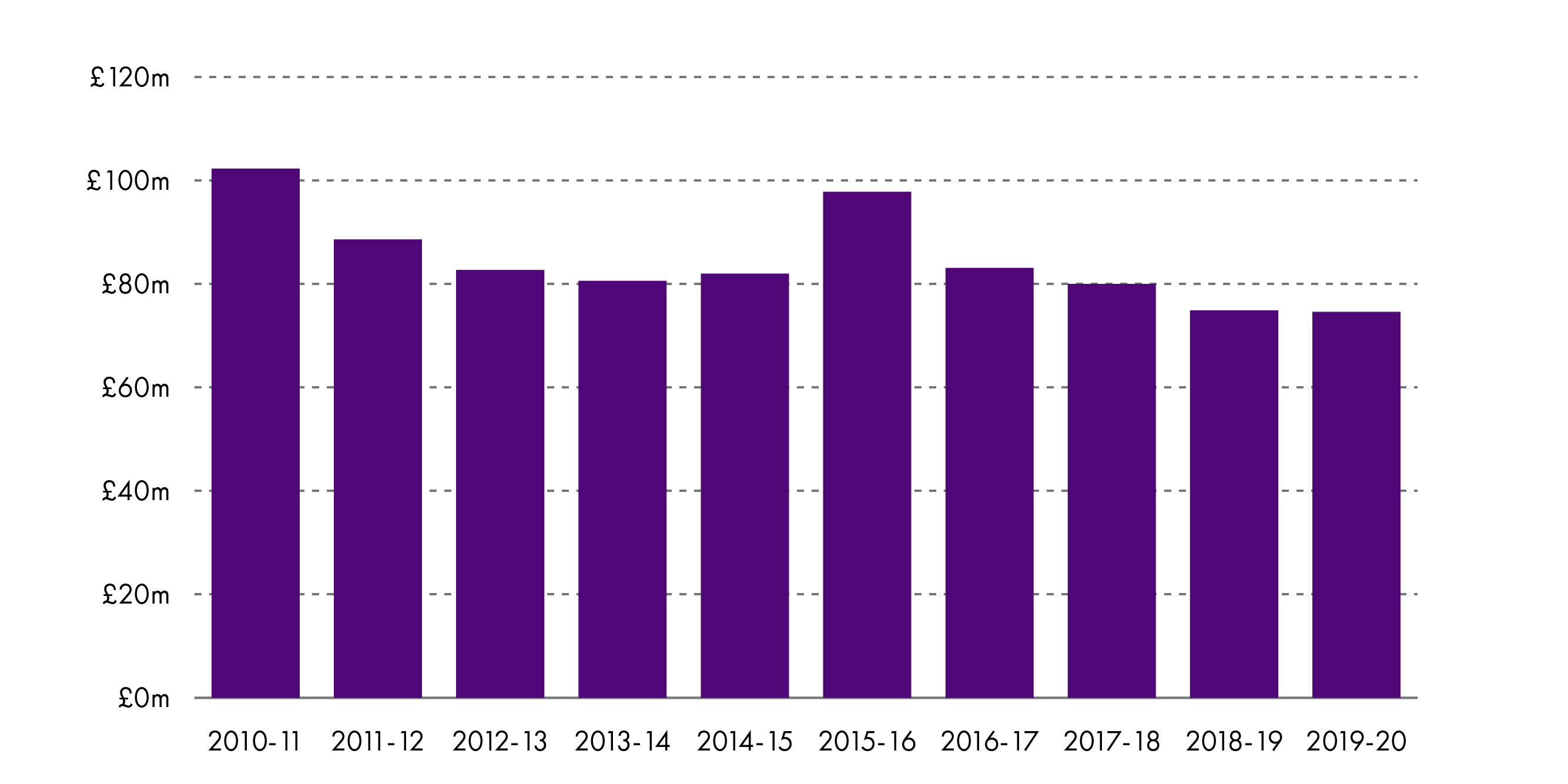

The “Creative Scotland and Other Arts” is a level 3 budget line within the Scottish Government’s budget. Figure 2 below shows financial allocations for this budget line from 2010-11 to 2019-20.

Figure 2: Scottish Government – Creative Scotland and Other Arts Budget Line (Level 3), 2010-11 to 2019-20, real terms (2019-20 prices)  Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Figure 2 shows that Creative Scotland’s core revenue budget has reduced over the period by approximately £9.2m at 2019-20 prices. The Other Arts budget line includes revenue funding managed by Creative Scotland. Until recently, this tended to be ringfenced Scottish Government funding (e.g. the Youth Music Initiative). In recent years, this has included funding to make up for a shortfall in National Lottery funds and support for screen, which is reflected in the increase in overall funding in 2018-19. This is considered in more detail in the section on Creative Scotland’s funding below.

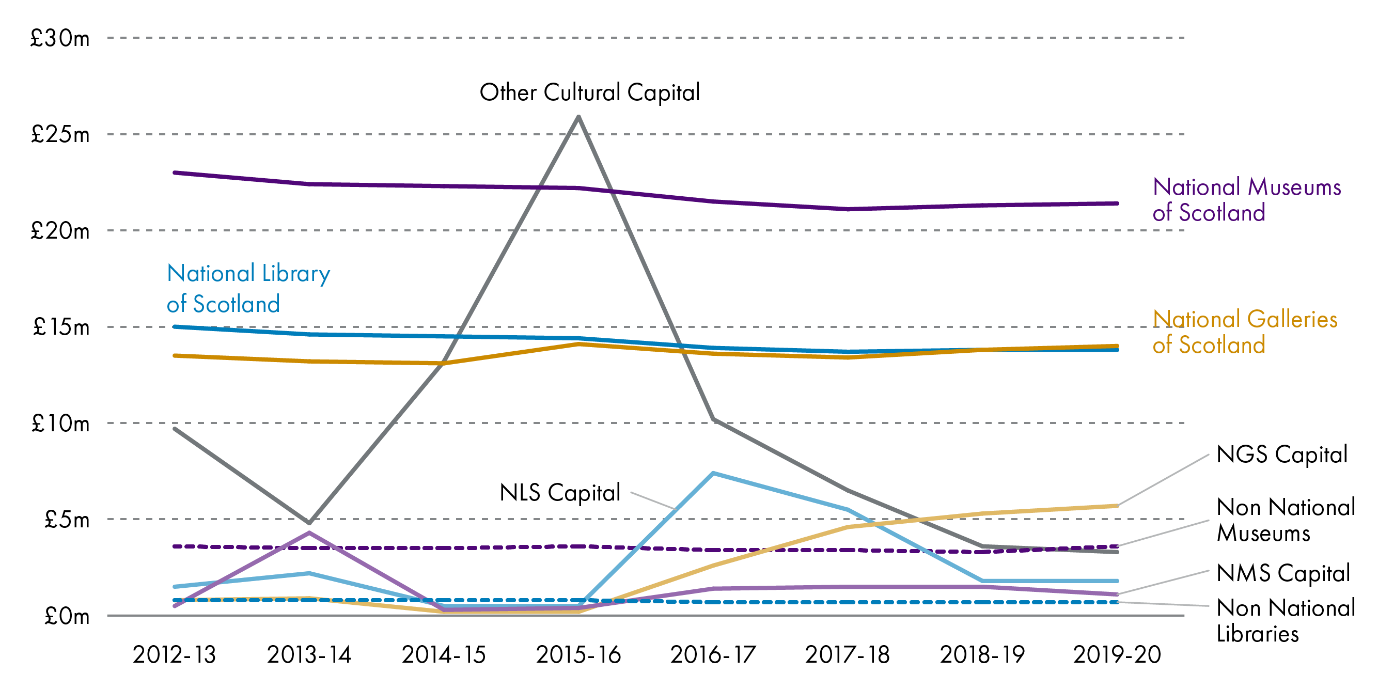

The Scottish Government also provides funding to Scotland’s cultural collections, which includes the National Galleries of Scotland,iii the National Museums of Scotland,iv the National Library of Scotland and the National Records of Scotland. Figure 3 below shows selected Level 4 budget lines for the cultural collections since 2012-13; and Figure 4 shows the level 3 cultural collection budget line since 2010-11.

Figure 3: Scottish Government – Cultural Collections Selected Budget Lines (Level 4 - not including non-cash or RCAHMS), real terms (2019-20 prices)  Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.Figure 4: Scottish Government – Cultural Collections Budget Line (Level 3), 2010-11 to 2019-20, real terms (2019-20 prices)  Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.v

Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.v

Figure 3 does not show all lines within the Cultural Collections Level 4 budget, for example it does not show the non-cash budgets (depreciation) or the budget for Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Level 4 figures for the Cultural Collections were also not available before 2012-13, as they were for Level 3 in Figure 4. Between 2015-16 and 2016-17 some of the capital was allocated in the individual national collections, rather than in “Other Cultural Capital”. The figure for 2015-16 “Other Cultural Capital” was particularly high due to costs for the V&A Dundee and other refurbishment projects. In terms of revenue, the national collections budgets have been stable with small cash terms increases, although this translates to real terms decreases of revenue funding for the National Galleries of Scotland, National Museum of Scotland and National Library of Scotland.

The Level 3 figures provided in Figure 4 (NB this includes more than just the Level 4 lines included in Figure 3) should be read in light of a discontinuity of funding in 2015-16 where the budget for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland was included for the last time. The budget figures in Figure 4 for 2015-16 is also affected by the unusually high capital budget for that year, as noted above. Notwithstanding these changes, there was a fall in funding between 2010-11 and 2012-13. Since then, taking account of the removal of RCAHMS and the spike in 2015-16, funding has been reasonably stable in real terms.

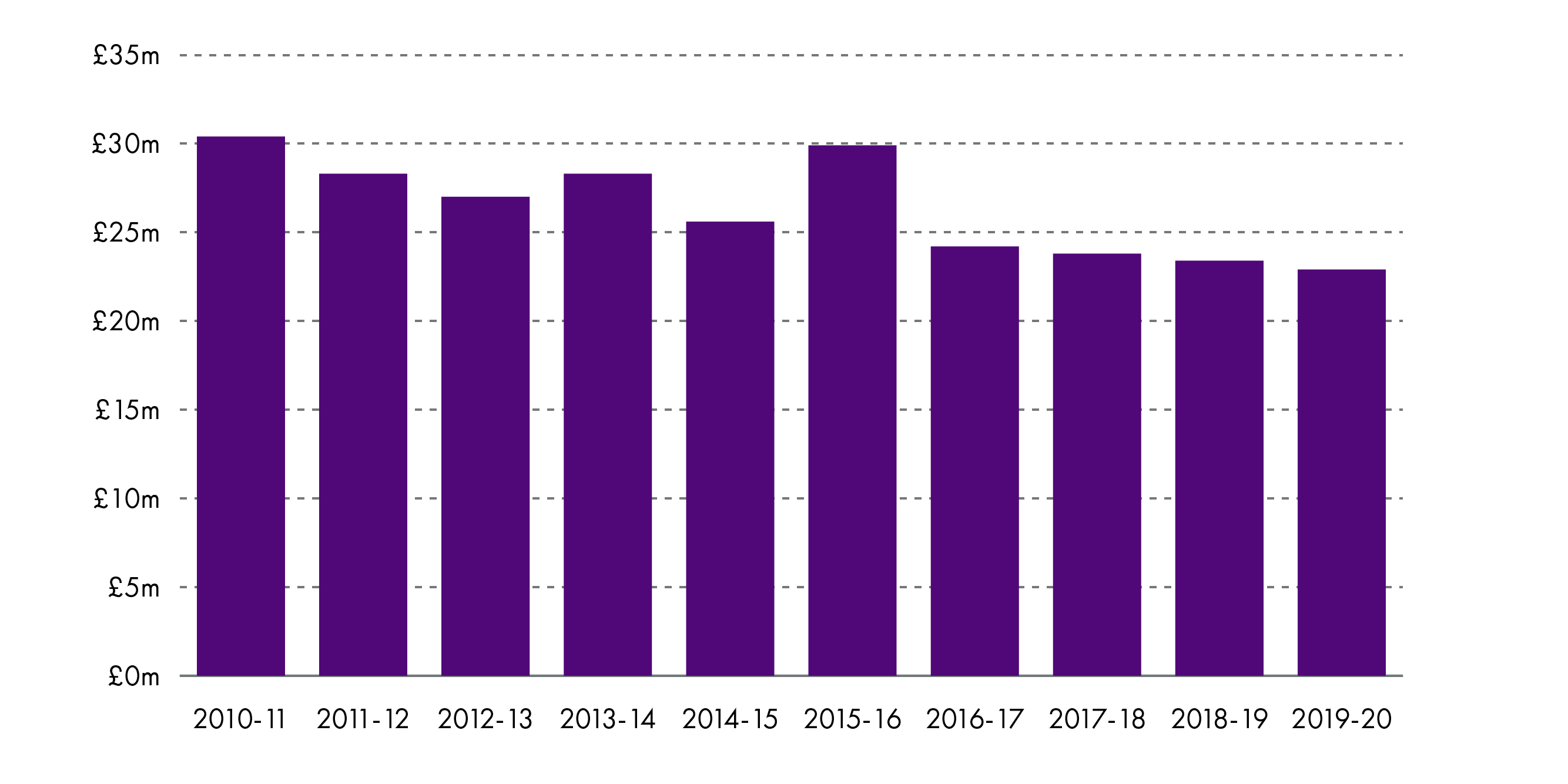

The Scottish Government also funds the five National Performing Companies through annual funding and the International Touring Fund (of which the current funding commitment is £350,000).vi Figure 5 below shows the level 3 figures for the National Performing Companies dating back to 2010-11.

Figure 5: Scottish Government – National Performing Companies Budget Line (Level 3), 2010-11 to 2019-20, real terms (2019-20 prices)  Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Scottish Government budgets and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

There has been a reduction in funding of the National Performing Companies over the period. Some of this reduction, however, may be due to how and where capital funding is accounted. Some figures are reported differently in different budgets (e.g. the figure for allocation in 13-14) and this appears to be due to the treatment of capital budgets. Nonetheless, the National Theatre of Scotland noted in its written submission to the Committee the negative impact that existing funding levels are having on its provision—

“The National Theatre of Scotland is in the privileged position of enjoying both an extremely positive relationship with government and also strong levels of financial support. Even given this, funding for the company has reduced by 21% since 2012 in real terms when actual reduction and inflation are taken into account. This comes at a time when costs have continued to rise, affecting our ability to make the sort of cultural provision we believe the Scottish people deserve.”vii

The National Theatre of Scotland’s evidence echoes wider concerns expressed in the evidence submitted to the Committee’s inquiry about downward pressure on public finances,viii particularly the impact this has had on the arts and culture portfolio in Scotland in the past decade.ix The Federation of Scottish Theatre noted that national funding for the arts in Scotland is currently a very small proportion of overall spend, representing "…much less than 1% of the total budget".x The Committee’s comparative research found in this regard that the UK as a whole spends a significantly lower proportion of GDP on culture than is the case in comparator EU countries.xi

In terms of what measures could be taken by the Scottish Government to maintain a sustainable level of funding for the arts, the Musicians’ Union suggested that the Scottish Government should aim to maintain funding levels in line with inflation,xii whilst Neo Productions and the Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland suggested that 1% of the Scottish Government’s budget should be ringfenced for spending on culture in line with the recommendation of the Cultural Commission (2005).xiii

The Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee that she considers the purpose of public funding for the arts is to "…help to ensure that individual artists are supported to produce art for art’s sake, and…The other strand is to help to support excellence in art."xiv In relation to overall national spending on the arts, the Cabinet Secretary stated that “I would rather look at ceilings than floors. With baselines, there is a danger that somebody sitting in a finance department who looks at matters from a financial accounting perspective might say, “Well, that’s all you need, so that’s all you’re getting.” Maybe that is not the right approach.”xiv

The Cabinet Secretary also told the Committee that her priority is on overall government funding for the arts, not simply the amount that is funded directly through her portfolio—

"I just want to ensure that there is funding. I am less concerned about where it comes from in the Government and more concerned about the total amount that I can get for all my areas. If I fought for the budget through a silo approach, to which Mike Rumbles referred, there would be a risk that I might end up with a bigger line on my budget but with a reduced contribution to the culture budget from other parts of the Government."xiv

The Cabinet Secretary also suggested that the forthcoming culture strategy will not be supported by additional funding, noting—

"I caution that the culture strategy will not involve a major funding announcement, as people might expect given the current constraints on budgets. However, it will be a statement of how we can work collectively across not just Government but local authorities, arts organisations and people outside the arts to leverage in more funding."xiv

The Committee notes the real-terms reduction in funding for the arts and the relatively low proportion of GDP spend on the arts compared to other EU countries. The Committee considers that the forthcoming culture strategy should be supported by a spending plan and a clear cross-government approach to supporting the arts and culture.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government articulate its spending plan for the forthcoming culture strategy, including what funding will be earmarked for the arts from other portfolios to deliver the national outcome on culture in a cross-cutting way. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give serious consideration to the culture strategy being supported, on a cross-portfolio basis, by a baseline target for national arts funding above 1% of the Scottish Government’s overall budget.

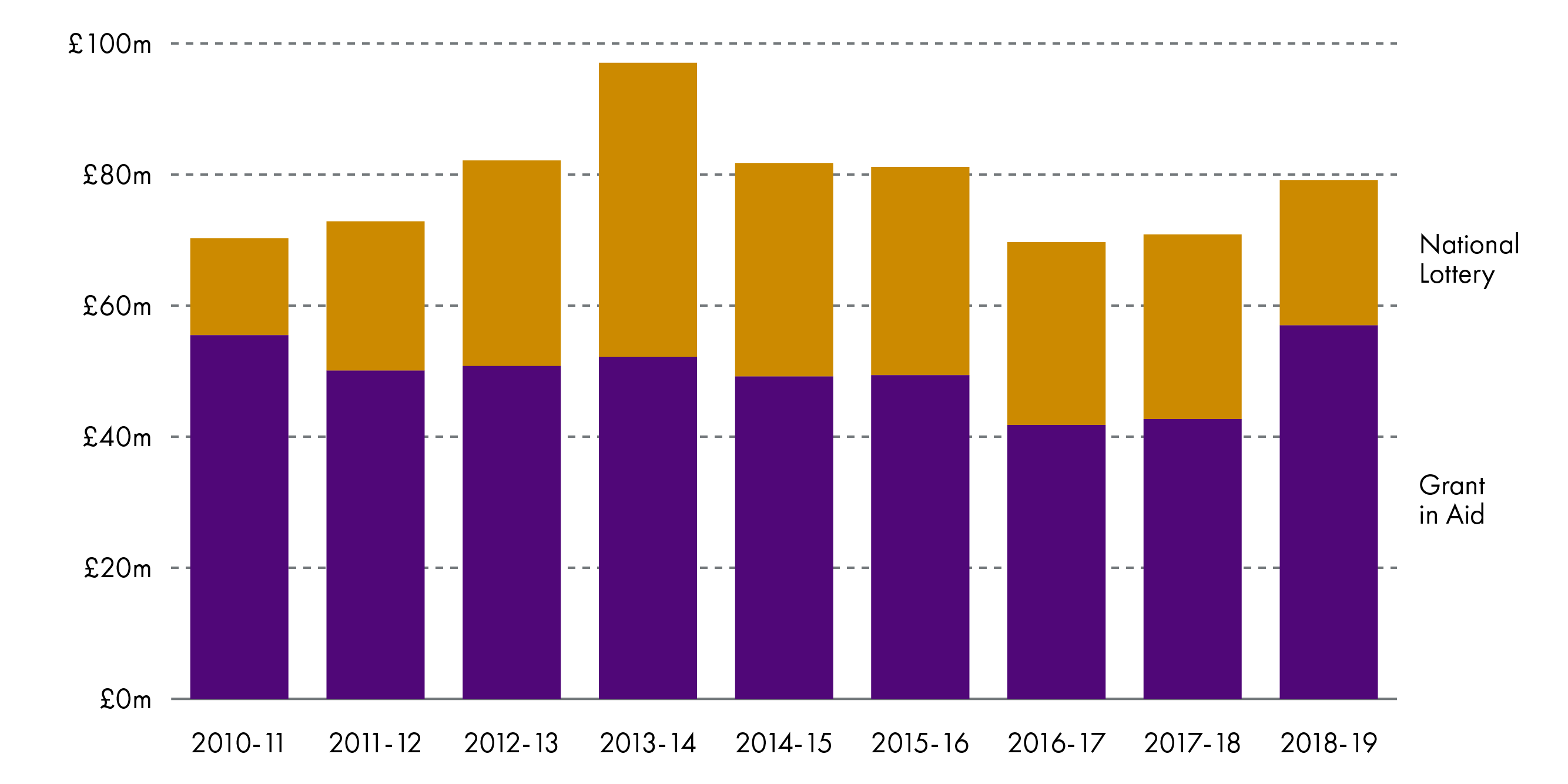

Creative Scotland

The majority of respondents to the Committee’s call for evidence commented on the national funding that is distributed by Creative Scotland. Creative Scotland’s budget is made up of a grant in aid from the Scottish Government and from income generated by sales from the National Lottery, which Creative Scotland distributes through its National Lottery Distribution Fund. The table below gives an overview of Creative Scotland’s real-terms grants from 2010-11 to 2018-19.

Figure 6: Creative Scotland Grants, 2010-11 to 2018-19, real terms (2018-19 prices)  Creative Scotland Annual Reports and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

Creative Scotland Annual Reports and SPICe communication with the Scottish Government.

It should be noted that the activities funded by the grant in aid shown above cover the full breadth of Creative Scotland’s remit, which includes activities such as screen that are outwith the scope of this inquiry. In real terms, the overall grants issued by Creative Scotland have increased since 2010-11, although there have been fluctuations within the period. For example, total Creative Scotland grant funding reached a high in 2013-14 and the total grant funding in 2018-19 was £17.9m less than in 2013-14 in real terms (18-19 prices). The proportion of the grants distributed by Creative Scotland that are funded through the National Lottery increased between 2010 to 2013-14, but since then the trend has been downward. Accordingly, this fluctuation in the overall level of Creative Scotland grant is largely accounted for by the decline in National Lottery income.

Grant in aid funding

The values of grants funded through the Scottish Government’s grant in aid increased significantly in 2018-19. As noted in the previous section, the Level 4 data for the 2018-19 budget includes the following commentary explaining the increase in the Other Arts budget line—

"Increased investment in screen announced in Programme for Government; increased support for Sistema Scotland and maintaining funding for Youth Music Initiative, both in Year of Young People. Also includes additional funding to enable Creative Scotland to maintain its support for the Regular Funded programme in the light of significantly decreasing lottery income."i

Iain Munro, then Acting Chief Executive of Creative Scotland, explained to the Committee the extent to which the Scottish Government has restricted the funding available to the organisation when he gave evidence on 2 May 2019—

"Our current income of £92 million a year consists of two parts: two thirds of it comes from grant in aid from the Scottish Government and a third of it comes from the national lottery. Of the two thirds from the Scottish Government, roughly half is restricted funds that are for specific purposes—I am referring to programmes that the Government wants us to run, such as the youth music initiative, the expo fund and the cashback for creativity programme. We use the other half of the grant in aid—the unrestricted funds—to support other activity. It is important to understand that 86 per cent of the unrestricted grant in aid is what currently funds 121 regularly funded organisations. That leaves very little room for manoeuvre in the current grant-in-aid balance in that equation, and it puts more pressure on national lottery funding."ii

The Scottish Contemporary Arts Network (“SCAN”) expressed concern about the increasing prevalence of the award of funding for the arts from Creative Scotland at standstill levels and the extent to which this is leading to a "…real concern among our members that they will reach breaking point. Standstill will become collapse."iii The Federation of Scottish Theatre also commented on the impact of real-terms decline in funding from Creative Scotland and how this is affecting the sustainability of the theatre sector, stating in its written submission that—

"More than two-thirds of our regularly-funded members received the same cash award from Creative Scotland for 2018-21 as they received for 2015-8, and for several this is the same cash amount as their grant in 2010 when Creative Scotland took over responsibility for funding. This is a real-terms cut of more than 25% in ten years and its impact on sustainability is palpable."iv

Some respondents commented that declining real-terms public funding for the arts in recent years has led to an unsustainable dependence by some artists and organisations in the sector on funding opportunities administered by Creative Scotland.v The Ayr Gaiety Partnership noted in this regard—

"There are many organisations, and much cultural activity in Scotland, which is almost entirely dependent on public funding…The results of the recent RFO decision process are testament to this – where organisations that did not secure funding have either closed, or in some cases have been sustained through substitution of their funding from one Creative Scotland funding stream (RFO) to another (OPF or Touring Fund)."vi

The Committee is aware of the significant personal and professional impact that unsuccessful funding bids can have on artists and those who are employed by artistic companies. For example, David Leddy, theatre director of the Fire Exit production company, explained that his company ceased operating in June 2019 as a result of not retaining Creative Scotland funding.ii

National Lottery funding

The National Lottery was created in 1994 with the aim of supporting good causes across the UK in the arts, sport, heritage and community sectors. A proportion of its proceeds are distributed through public bodies, including Creative Scotland, to achieve these aims.viii The Scottish Government provides directives to Creative Scotland as to how proceeds from the National Lottery are to be distributed.ix The National Lottery provides a substantial proportion of Creative Scotland’s overall budget, representing 30% in 2018/19. As noted earlier, Creative Scotland’s core grant is allocated towards its regular funding programme, whilst “…the two remaining funding routes we offer (Open Project Funding and Targeted Funding) are largely only possible through The National Lottery”.x

Some respondents, such as Dogstar Theatre, were critical of the Scottish Government’s reliance on the National Lottery as a funding supplement to its own core grant contribution to Creative Scotland’s budget, noting that—

"The introduction of lottery funding in the late ‘90s was welcomed, by and large, but this has increasingly proved to be a sticking plaster, a fund which has enabled government to reduce its own tax-funded contribution to our arts production and infrastructure."xi

The vulnerability of Creative Scotland’s programme delivery to fluctuations in National Lottery income was demonstrated when the Scottish Government committed up to an additional £6.6 million to Creative Scotland to cover the potential shortfall in lottery funding for 2018-19.xii In addition, the Scottish Government committed to taking "…the exceptional step of guaranteeing this core grant in aid and the additional £6.6 million for each of the next 3 financial years…"xii

Despite the short-term measures taken by the Scottish Government to protect the potential shortfall in Creative Scotland’s income from the National Lottery, questions remain over the sustainability of Creative Scotland’s funding package. Potential threats to the sustainability of this model that were highlighted to the Committee include increased competition in lottery sales and changes to lottery regulation,xiv which is a reserved matter. In this regard, the National Lottery’s licence holder, Camelot Ltd, responded to the Committee’s call for evidence arguing that the UK Government’s proposed reforms to society lottery regulationxv is "a major threat to sustainable funding of the arts in Scotland".xvi This view appears to be shared by Creative Scotland, which noted in its written evidence to the Committee that—

"The National Lottery has recently been under challenge from competition from other lotteries, particularly Society Lotteries. This has led to fluctuations and volatility in the income being generated and subsequently distributed. The recent impact on Creative Scotland has been a fall in income from The National Lottery of some £6million."xvii

The People’s Postcode Lottery, a society lottery, did not recognise this characterisation of the UK Government’s proposed reforms. It stated in response to the Committee’s call for views that "society lottery reform is not about competing with the National Lottery. It is about increasing the outdated annual sales limit contained in the 2005 Gambling Act…"xviii The People’s Postcode Lottery noted that one of the charities under its umbrella, the Postcode Culture Trust, has given a total of £13.8m in funding to 55 organisations in Scotland.xviii The Committee is also aware of funding that is awarded by other society lotteries and private trusts towards the arts and culture in Scotland. A key difference with the award of funding from Creative Scotland’s National Lottery Distribution Fund, as opposed to society lotteries and private trusts, is that National Lottery funding must be awarded in accordance with policy directives from the Scottish Government and in line with the National Performance Framework more broadly.

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (“DCMS”) published the findings of its consultation on society lottery reform on 16 July 2019, in which it announced its intention to progress with its proposed reform of the regulation of large society lotteries. This will involve increasing the individual per draw sales limit from £4 million to £5 million; increasing the individual per draw prize limit from £400,000 to £500,000; and increasing the annual sales limit from £10 million to £50 million.xx DCMS also stated its intention to run a further consultation to introduce a split tier licence for large society lotteries for an upper tier licence of £100 million.i

Given these changes in the wider lottery market, some respondents to the Committee’s call for views called for the Scottish Government to set out a long-term strategy to find a sustainable funding replacement for the National Lottery.xxii Aberdeen City Council suggested, for example, that the Scottish Government should consider establishing new investment funds to supplement or replace the National Lottery, such as through the Scottish Government’s proposals for a Scottish National Investment Bank.xxiii The potential opportunities presented by the Scottish National Investment Bank for innovative investment in the arts was also supported by other respondents to the call for evidence.xxiv

The Scottish Government’s draft Culture Strategy outlined a commitment to explore new funding models to support a sustainable culture sector, including through a Scottish National Investment Bank and devolved tax powers.xxv The 2019-20 Programme for Government committed to making the Scottish National Investment Bank operational in 2020 and to "put the transition to net zero at the heart of the Scottish National Investment Bank’s work".xxvi The Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee concluded in its stage 1 report on the Scottish National Investment Bank Bill, dated 4 July 2019, that "people have such high expectations for the Bank that it is unlikely it can deliver on everything to which its name has been speculatively attached before even a single mission is framed or its first investment made."xxvii

The Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee that the Scottish National Investment Bank will play a limited role in creating a sustainable arts funding system for the future, noting—

"We need to be clear that the Scottish national investment bank will operate on a commercial basis, so it will not fund on a grant basis and I expect that its support for the creative industries will be limited…I think that it was Aberdeen City Council that suggested that we could somehow replace national lottery funding with funding from the Scottish national investment bank. I thought that that was a really odd suggestion."ii

The Cabinet Secretary noted the kinds of activity funded by the National Lottery is more likely to cover non-commercial activity, when she explained—

"There is a spectrum of funding—it goes from what is commercial funding to funding art for art’s sake. In that spectrum, the national lottery would be sitting at one end, and anything that was obtained from the Scottish national investment bank would be at the other end for the more commercial creative industries. I therefore caution the committee about how it approaches that issue."ii

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s approach in the short-term to protect Creative Scotland’s budget from decline in National Lottery income over three financial years. The Committee is not clear from the Scottish Government’s evidence what other measures are being investigated to provide a sustainable funding model for the future in the event of continuing fluctuations in National Lottery income.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should articulate a long-term strategy for protecting Creative Scotland’s budget from fluctuations in National Lottery income and to do so before its existing commitment in the short-term to protecting Creative Scotland’s budget expires.

European Funding

The Committee’s inquiry also considered the sources of funding available from EU programmes and how Brexit may impact on the sustainability of public funding for the arts.i Direct and indirect funding of the arts comes from many European sources, including the Creative Europe Programme, Erasmus+ and European Structural and Investment Funds. In this regard, Creative Scotland commissioned UK-based consultancy company, Euclid, to identify EU-funded projects focused on or linked to the arts, media and creative industries in the last ten years.ii The report found that “two thirds of this funding had come from European structural funds rather than culture specific programmes”.iii

Creative Scotland hosts the Scotland office of the Creative Europe Desk UK, which provides free information and advice to Scottish creative, cultural and heritage organisations on Creative Europe projects, partnerships and applications. The office also signposts potential applicants to information on other EU funding programmes such as Erasmus+, Europe for Citizens and Horizon 2020.iii

The Creative Europe Desk UK’s written submission explained how EU programmes, such as the Creative Europe programme, provide opportunities to attract additional investment in Scotland’s artists.v In this regard, the submission underlined that the Creative Europe programme follows the subsidiarity principle, such that "it extends and adds value to national support". Accordingly, the funding available from the programme "…will always require national co-funding sources". The submission also noted that it is "…important that local, regional and national funding institutions respond to multilateral programmes such as Creative Europe, and understand the leveraging effect of enabling organisations to put themselves forward for these pan European initiatives…"vi

Many respondents to the Committee’s inquiry, including the Creative Europe Desk UK, expressed support for Scotland remaining part of the Creative Europe programme and other relevant EU funding programmes if the UK leaves the EU.vii Non-EU countries are able to participate in the Creative Europe programme if they meet certain conditions.viii The Creative Europe Desk UK noted in this regard that it has been working with the DCMS to assist them in pursuing the option for the UK to continue participating in the Creative Europe programme after Brexit.ix

Non-EU countries are not able to benefit from European Structural and Investment Funds and for this reason the UK Government proposes to replace this source of funding after Brexit with a new UK-wide programme, the Shared Prosperity Fund. Creative Scotland emphasised to the Committee in its written submission that "…any UK Government funding that replaces EU structural funding is very important to the creative sectors in Scotland."iii This view was shared by other stakeholders, such as the Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland which highlighted that the potential loss of access to this funding could result in a real-terms decrease in available funding because the amount currently invested in the UK is “proportionally greater in return than the proportion of the funding the UK contributes”.xi

Creative Scotland has also argued that the existing level of funding available through the European Structural and Investment Funds should continue after Brexit—

"We strongly advocate that post-Brexit structural funds should, as a minimum, match this current contribution for cultural activity in Scotland. We do, however, believe there is an opportunity for development through establishing priorities and models of support which allow for arts and culture to play a greater role in tackling inequality and supporting inclusive growth."iii

Creative Scotland has expressed concern over the lack of clarity on what the replacement scheme, the Shared Prosperity Fund, will entail, noting that—

"Exactly what this fund would be and how it will operate has been difficult to establish and Creative Scotland and the UK Arts Councils have been maintaining a close dialogue to share intelligence on any proposals from the UK Government that continue or replace EU funding."iii

The Scottish Government launched a consultation on its priorities for the Shared Prosperity Fund after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on 5 November 2019.xiv The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee in relation to Brexit that—

"My biggest immediate concern is that programmes that are live just now should continue to be funded. I will do what I can, as part of our Brexit planning, but it would be wrong of the Scottish Government to say that it will be able to mitigate the worst excesses of the UK Government’s actions in not providing detail."xv

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should seek to maintain Scotland’s participation in the Creative Europe programme after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give consideration to arts funding as part of its consultation on the replacement of European Structural Funds after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

Local Government Funding

Local government plays an essential role in the funding of the arts. Local authorities are tasked with interpreting national policy in a local context to deliver cultural services in a way that is responsive to local needs and circumstances. The funding landscape for the arts and culture at a local authority level has been complicated by many factors, including differing interpretations of the duties on local authorities to provide cultural services; the creation of arms-length external organisations (‘ALEOs’) by many local authorities to deliver cultural services; and the impact of wider pressures on local authority finances on policy delivery. These issues are considered in turn in light of overall trends in local government spend for culture and related services since 2011-12.

Statutory framework and responses to ring-fencing

The statutory framework that underpins local authorities’ duties in respect of cultural provision is complex. Generally speaking, local authorities are required to make adequate provision for culture and related services. The 2003 guidance that accompanied the then Scottish Executive’ culture strategy set out the four main statutes that were relevant to ‘adequate provision’, including Public Libraries Consolidation (Scotland) Act 1887; Local Government and Planning Act (Scotland) 1982; Local Government (Scotland) Act 1994; and Local Government in Scotland Act 2003.i Since then, Part 2 (sections 15 to 19) of the Local Government in Scotland Act 2003, relating to Community Planning, has been replaced by Part 2 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. The Scottish Government has also implemented a policy of public service reform in light of recommendations made by the Christie Commission in 2011 and the launch of a refreshed National Performance Framework.

Many respondents to the call for evidence considered that ‘adequate provision’ is a subjective term, which has made the leisure and culture portfolio vulnerable to funding cuts.ii Indeed, this issue is not new and was recognised in the implementation guidance for local authorities that accompanied the then Scottish Executive’s National Cultural Strategy in 2000. The guidance stated—

"In some respects, the legislation is vague in relation to the principal duties and powers, and, in particular, relating to ‘adequate provision’. As a result, it is believed that there is variation between individual local authorities – which have interpreted it differently, in accordance with their own policy priorities and resource availability."i

The then guidance provided some direction to local authorities about how to ensure cultural provision was ‘adequate’ and therefore in line with their statutory duties. Examples of the measures that local authorities were suggested to take included the development of an authority-wide culture strategy and service-specific plans.i There is no Scottish Government guidance currently availablev as to how local authorities should interpret ‘adequate provision’ and in this respect the local-national policy framework appears to be unclear. This is considered in more detail in the following chapter of this report.

The interplay between local authorities’ statutory duties, the local government settlement and the funding allocated by local authorities to specific policy areas, including the arts, was an issued raised by respondents to the inquiry. The Committee notes in this regard that the Scottish Government’s definition of 'ring-fencing' in the context of the local government settlement is different to COSLA’s definition of 'non-discretionary' or 'protected spend'.vi Notwithstanding this, the Committee heard contrasting views on how local authorities could best utilise their budgets to support the arts and cultural provision.

Stewart Murdoch, Director of Leisure and Culture Dundee, told the Committee for example that being outside protected funding put the arts and culture at a 'disadvantage'.vii Glasgow Life agreed that protecting the spending of other portfolios means that the funds available for the arts "…have been disproportionately affected".viii It cited Canada and Singapore as international examples where cultural spending has been ring-fenced successfully.ix Leonie Bell, Paisley Partnership Strategic Lead for Renfrewshire Council, argued against ring-fencing of arts funding on the basis that it is difficult to define what is meant by the arts and culture in a spending context. In her view, "we need to start with the ambition, the strategy and the policy before we look at budget mechanisms".vii

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that she remains open to working with local authorities on support for the arts. The Cabinet Secretary stated—

"I am very keen to meet and encourage all the local authority culture conveners. I need COSLA to engage with me on that, but I have found it to be an increasingly frustrating and difficult exercise. I will keep pursuing that. If we work together in tandem, we can do great things, even in difficult times. It is not all about the level of funding; it is about political will as well."vii

ALEOs and the delivery of cultural services

Another issue raised by respondents to the inquiry was the impact of ALEOs on funding for the arts at a local government level. A report by the Audit Commission estimates that approximately 20 councils have created an ALEO to deliver cultural services, 13 of which have a joint leisure and culture remit.i A major incentive for creating ALEOs to deliver cultural services appears to be cost saving, which can be made through levers, such as rates relief. Stewart Murdoch, Director of the Leisure and Culture Dundee ALEO, told the Committee "there is no question but that it has enabled the City of Dundee Council to make significant savings."ii This view was also expressed by the Barclay Review, which found that the ALEO model “…allows councils to gain additional funding from the Scottish Government outwith the usual funding arrangements, a fact that was acknowledged by councils themselves as one of the primary reasons they put services into ALEO status in the first place”.iii

The Committee also became aware of potential issues that the ALEO model can give rise to, such as local accountability over policy priorities and spending. In this regard, Stewart Murdoch told the Committee—

"If the ALEO is not represented on the council’s management team, the leader of the ALEO will not be at the table when the other chief officers have a discussion about budget setting or priorities, and they will not have influence. In the case of Dundee City Council and Glasgow City Council—I am not sure about the situation in other councils—the ALEO is considered. The leader of the ALEO is part of the council’s management team, as well as running the ALEO. There is a visible tension, because the ALEO is independent. It is challenging to take part in those discussions and to separate oneself from that when it comes to the delivery end of the ALEO, but that dual role is important in the ALEO model. Without it, there would be no one in the local authority management team advocating for investment in culture."iv

The Committee did not have time within the scope of this inquiry to consider the impact of ALEOs on arts funding and the extent to which any savings made through the use of this model have been reinvested in the arts specifically, as opposed to other policy areas. It noted, however, that national data analysing the savings (or otherwise) derived from ALEOs was not readily accessible. The Committee is not aware of any Scottish Government guidance on the issues highlighted in evidence about local authorities’ management structure in respect of ALEOs.v

The Cabinet Secretary noted that the development of ALEOs and their impact with regard to the governance of local services is not a new issue, as it was the subject of a previous parliamentary committee in Session 4.iv The Cabinet Secretary explained that whilst she has had positive engagement with ALEOs, through the umbrella body VOCAL, difficulties in ascertaining how cultural provision is being made at a local authority level through ALEOs persist—

"I prefer to support people who want to do things. There is a danger in that regard: some local authorities have absolutely decimated their culture funding, while others—East Ayrshire Council, Perth and Kinross Council and Stirling Council—have had positive experiences. It is hard to tell what local authorities are doing because so many of them now work through trusts."ii

Local government spend for culture and related services 2011/12 – 2017/18

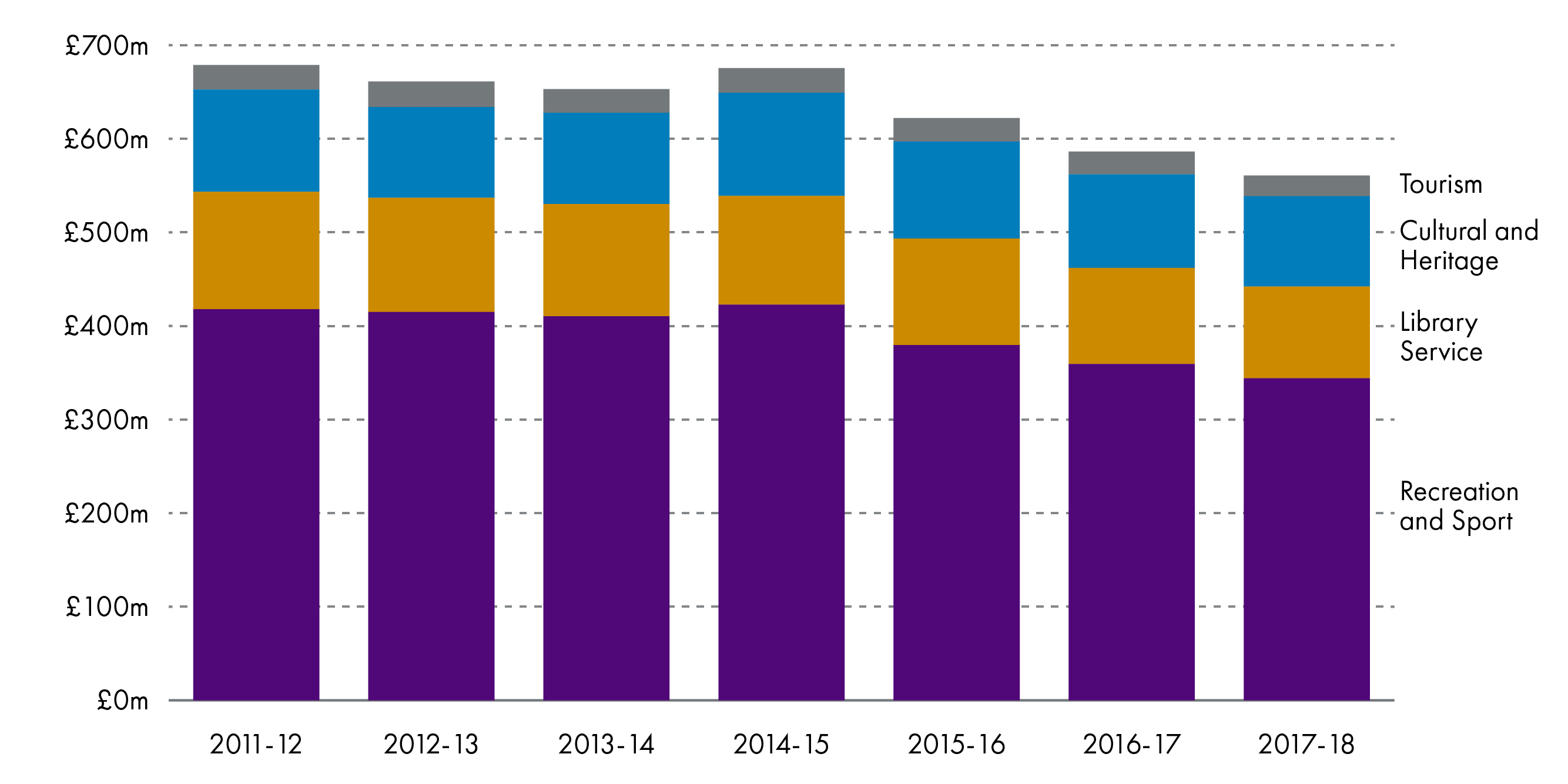

The figures below show the general trend in local government spend for culture and related services since 2011-12—

Figure 7: Culture and Related Services: Net Revenue Expenditure, 2011-12 to 2017-18, real terms (2017-18 prices)  2011-12 to 2017-18 Local Financial Returns (LFR 02) HMT Deflators Sept 2019.

2011-12 to 2017-18 Local Financial Returns (LFR 02) HMT Deflators Sept 2019.

Figure 7 above shows decreasing real terms net expenditure by local authorities across culture and related services. It also highlights the relatively small amount spent on libraries, as well as cultural and heritage policy, as compared with recreation and sport. The budget line for cultural and heritage spend are very broad in terms of the types of activity that are included within them and so it is difficult to ascertain from local authority budget figures exactly how much is being spent on the arts directly.

It should also be noted that Figure 7 presents net expenditure, which is the amount of spend funded by the general revenue grant from the Scottish Government, non-domestic rates income, council tax receipts, and reserves. It does not include expenditure funded through fees or charges. As such, it is not clear from these figures alone whether any decrease in local authority expenditure is being met by increased charges for services. As noted earlier in this report, the figures also do not take account of the impact of ALEOs across Scotland and what impact, if any this has had on spending on the arts and culture in the relevant period.

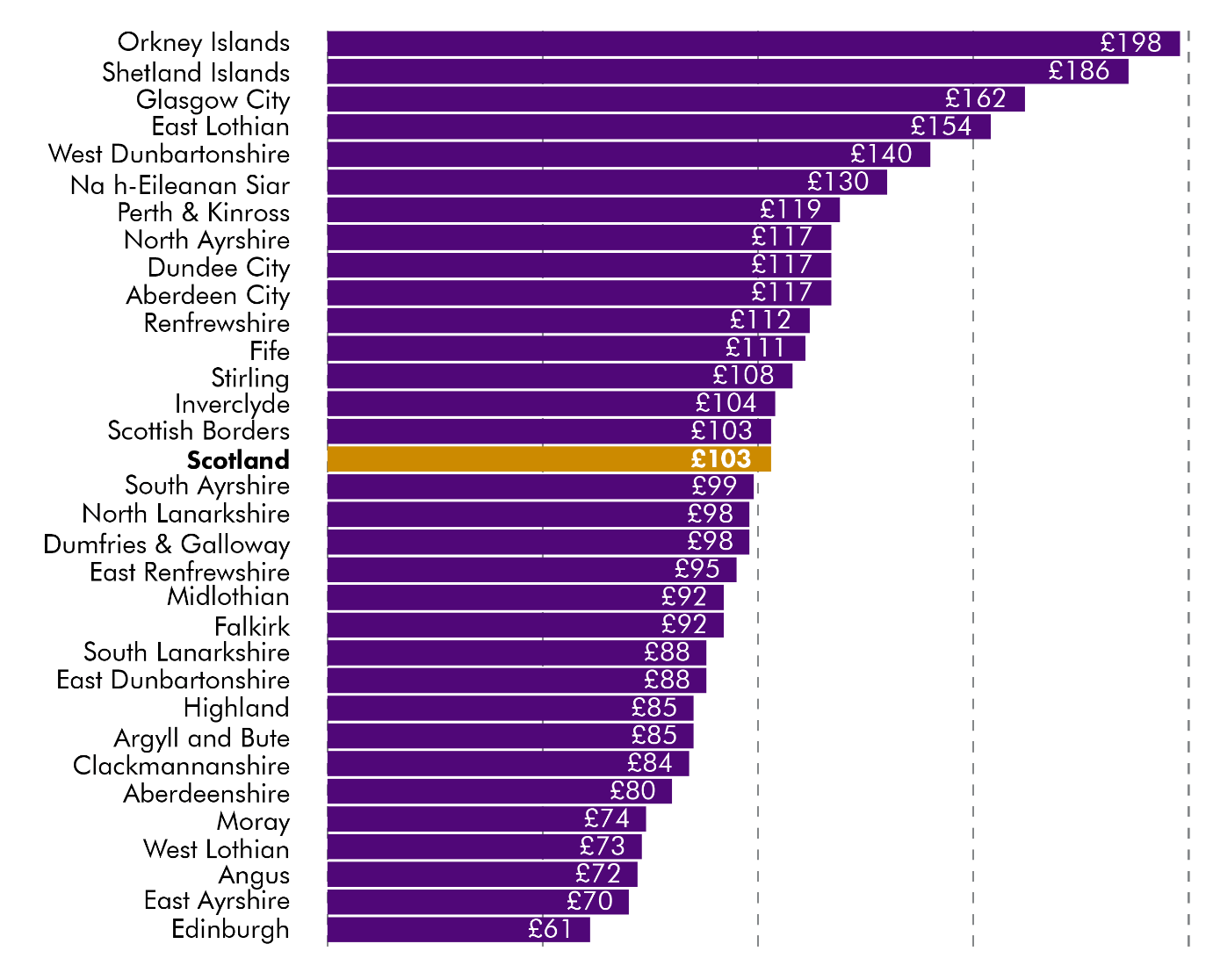

Incomplete data on local authority expenditure on culture

The Committee also examined the relative spending of local authorities on culture and related services per head of population. Figure 8 below provides an illustrative snapshot of local authority spend per head of population in 2017-18 (covering spending on Culture and Heritage, Tourism, Recreation and Sport and Library Services). The snapshot shows that, if you were to analyse the available data, it provides an incomplete representation of expenditure by local authorities on culture. The Committee recognises that there are distinctly different contexts in which local authorities undertake cultural expenditure. For example, Edinburgh has a number of nationally funded institutions, whereas Glasgow supports a range of cultural institutions with a national reach.

The type of budget data shown in Figure 8 is routinely used to measure and monitor local authority spending on culture, yet the data itself does not provide a clear or accurate picture of this spending. This is because it includes a wide variety of activities included in the figures (such as those relating to tourism, recreation and sport), as highlighted in Figure 7.

Notwithstanding the issue of data quality, the Committee’s inquiry has highlighted the significant disparity in funding and approaches to supporting the arts across Scotland’s local authorities. Indeed, the Cabinet Secretary described the level of disparity in funding between local authorities as “quite striking”.i The Committee considers that this situation threatens the sustainability of support for the arts across all parts of Scotland and must be addressed.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government, its agencies and local authorities need to reset their relationship in relation to arts and culture policy, including approaches to funding. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government adopt a proactive approach to re-engaging with all local authorities to discuss shared priorities for spending and to share best practice in leveraging investment in the arts.

Data to support evidence-based policy making

It has become apparent in the course of this inquiry that it is difficult to find accessible data that presents an authoritative picture of arts funding at a local and national level. The Committee was informed that individual artists and arts organisations have therefore carried the burden of demonstrating the impact of and outcomes of arts funding in circumstances where an overarching data framework or local and national open-source data resources is lacking.i It was also noted that extensive data is collected by Creative Scotland (in addition to other public funders) but that it does not have the capacity to “mine the data and learn from it”.i This has resulted in a number of individual projects being established to address the data gap in a piecemeal way.iii

Scotland is not alone in facing this challenge, as the Committee found from its comparative research that other European countries have established cultural observatories that are specifically tasked with addressing this issue, such as France and Ireland. The Committee also received evidence from the Creative Europe Desk UK that there is a proposal for the next EU multi-annual financial framework to establish a European observatory for Culture and Creative Sectors “to collect much needed data and statistics”.iv

The Committee was informed that Scotland already benefits from relevant expertise and resources that could be pooled together to address this issue, including (but not limited to) the Scottish Data Lab, the School of Informatics at the University of Edinburgh, and the Scottish Funding Council.i It was also noted that the Scottish Government could “become a world leader in how culture works” if it was to build on the use of existing data planning tools from elsewhere, such as WhiteBox,vi to support the better data and evidence-based policy making.i

The Scottish Government has expressed an intention to use culture to deliver wider policy outcomes in the National Performance Framework in a cross-cutting way.viii Whilst this intention is welcomed, it will add another level of complexity to the funding environment meaning that it may be difficult to measure spend and outcomes without better and more accessible data. In this regard, the Scottish Government’s draft Culture Strategy included a commitment to monitor the impact of the Strategy through the establishment of a Measuring Change Group.

The Cabinet Secretary noted that she was not able to make policy announcements during the purdah period, but underlined that within the draft culture strategy “…the strand on how we can measure performance and change was a strong one.”i The Cabinet Secretary also reflected on the evidence from Irish Arts Council and the Committee’s comparative research and noted—

"I was interested to note that the data gathering and observation that take place in Ireland, which are funded by the Irish Research Council, will be independent of Government. Each country will do these things in a way that suits it, but I am interested in that direction of travel."i

The Committee’s inquiry has highlighted the complex local and national funding framework that supports the arts in Scotland. The National Performance Framework places outcomes at the heart of Scottish policy-making and good quality and accessible data will be key to measuring progress and demonstrating impact. The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s proposal to establish a Measuring Change Group to ensure that the impact of the forthcoming culture strategy is captured and measured accordingly.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government establish an independent national cultural observatory in consultation with local government, relevant agencies and stakeholders. The purpose of the observatory should be to create and manage an open-source national data resource that will draw together existing information collated by all levels of government and relevant agencies to measure the spread and impact of the public funding of the arts across Scotland.

The Committee considers the data on local authority cultural expenditure to be inadequate as it may currently encompass culture, tourism, heritage and sport expenditure. The Committee also notes that local authorities diverge widely in their approach to cultural expenditure. The Committee recommends that culture spend is disaggregated and provided separately.

Part 2: Re-Setting Local & National Policy Alignment

The previous section outlined the existing funding environment and the challenges that must be faced in order to maintain a sustainable arts funding system for the long-term. In this restrained funding environment, the Committee investigated the extent to which national and local government have developed and deployed coherent strategies to articulate their investment priorities and identify additional funding opportunities to maximise and strengthen investment in the arts. This section highlights different loci through which local and national co-ordination occurs and considers means by which this could be strengthened.

Embedding the arts in local priorities and policy-making

The National Performance Framework recognises the important role that local government plays in delivering the national performance outcomes. It states that “To achieve the national outcomes, the National Performance Framework aims to get everyone in Scotland to work together. This includes: national and local government…”i The delivery plan also notes that, at a local level, community planning partnerships will develop local outcomes improvement plans.i However, the underlying legislation falls short in requiring community planning partnerships to take account of national policy and priorities in the development of these plans.iii

Audit Scotland’s Local Government in Scotland report recognises the wider role that local authorities play in delivering national outcomes, whilst acknowledging the pressure on them to deliver more for less—

"Scottish Government revenue funding to councils has reduced in real terms between 2013/14 and 2019/20, while national policy initiatives continue to make up an increasing proportion of council budgets. This reduces the flexibility councils have for deciding how they plan to use funding. At the same time, demand for council services are increasing from a changing population profile. All councils expect an increase in the proportion of people aged over 65 and almost a third of councils expect an increase in the proportion of children under 15."iv

The Cabinet Secretary reiterated in this regard that public funding “…is under pressure for us and for everybody”,v and noted the impact that budgets the Scottish Government have protected are having on culture—

"…the health budget has been protected, as has the policing budget in the justice portfolio. Because the health budget is so big, all non-protected budgets have had to be reduced to help to continue the support for the health budget in pressured times. That is the reality."v

Local cultural strategies

The essential role that local government plays in delivering cultural provision has been recognised since the beginning of devolution. The Scottish Executive’s first culture strategy dated 2000, Creating our Future…Minding our Past, noted in this regard that “local authorities are responsible for the majority of public support for cultural provision and guidance”.i The guidance that accompanied the then national strategy noted that local authorities should take action to implement the strategy and develop their own “single authority-wide cultural strategy and consider service-specific plans relating to key areas of provision” in order to ensure that they met their statutory duties.ii

In the course of its inquiry, the Committee was informed that some local authorities have developed, or are in the process of developing, culture strategies and that this was viewed generally as a positive policy and budgetary tool.iii In some cases, such as Renfrewshire and Dundee, the development of a cultural strategy appears to have been strongly influenced by the bidding process for the UK City of Culture scheme.iv Stewart Murdoch, Director of Leisure and Culture Dundee, noted that the development and implementation of a local culture strategy has been very effective in mainstreaming the arts and culture into wider strategic decision-making in Dundee—

"The one thing that Dundee has done is maintain a cultural strategy… since Government guidance about putting in place such strategies was published. That has helped us. We report our cultural strategy to the Dundee partnership, which is the local community and planning partnership for the city. For more than 15 years, we have been reporting to the community planning partnership on the strategic decisions and our action plan. There is no security for that, which is why it is not common across Scotland. However, it has been really helpful to have that focus, which is reported to the council and its strategic partners."iv

The Committee also received evidence of other initiatives to develop local culture strategies, such as in Aberdeen. Culture Aberdeen, which is a network of local organisations, worked with Aberdeen City Council to develop a ten-year culture strategy for the city. Culture Aberdeen explained in written evidence that this strategy “…has been developed within the context of relevant local and national strategies, including the emerging National Cultural Strategy, the Local Outcome Improvement Plan, the revised National Performance Framework, and Creative Scotland’s strategy”.vi The Committee also heard that Dumfries and Galloway is also currently developing a culture strategy.iv

The Committee also undertook two fact-finding visits to Ayr and Dunfermline to understand how culture and the arts is supported at a local level. It was evident from these visits that local priorities play a significant role in shaping funding opportunities for the arts and culture. Fife, for example, has outsourced its cultural services delivery to an ALEO, OnFife. It has a local cultural strategy, which was ‘driven by the Fife Cultural Consortium, a diverse group of 300 members from across its cultural, health, economic and community planning spectrums…”viii One of the three arms of the strategy is focused on “Strengthening and Developing Fife’s Creative Economy”viii and the Committee was informed by some artists during its visit to Dunfermline that the implementation of the local culture strategy appears to prioritise funding of the arts where there are demonstratable outcomes for supporting and growing tourism.x

It was also clear to the Committee from both visits the impact that local champions of the arts were having on their community. The Committee learned during its visit to Dunfermline, for example, how individual artists in Dunfermline were instrumental in developing the Fire Station Collective, an innovative model for supporting and showcasing local artists, whilst also providing a unique cultural venue for the benefit of local people.x In Ayr, the Committee witnessed how Ayrshire College is providing opportunities for young graduates to pursue artistic careers through free rehearsal space and careers guidance.xii The Committee also saw the significant positive impact that individual mentors can have on young artists in their community when it met with young sculptors and visual artists and their mentors in Ayr.

In neither area, however, was it clear to the Committee how the local authorities’ priorities for arts funding were influenced by or related to the national priorities for the arts and culture, as articulated in the National Performance Framework or Creative Scotland’s 10-year strategy “Unlocking Potential – Embracing Ambition”. The Committee considered this issue in more detail in an evidence session on 27 June.ii Leonie Bell, Paisley Partnership Strategic Lead for Renfrewshire Council, told the Committee at this meeting that more could be done to develop relationships between local and national government around the National Performance Framework in relation to the national outcome on culture—

"Perhaps there is a bit of work to do with the [national] outcome and how to develop the relationships or the framework around it, rather than creating another system—another set of agreements and structures."iv

In this regard, Gary Cameron, Head of Place Partnerships for Creative Scotland, suggested a more robust approach is required to mandate that local authorities should plan for and articulate their priorities for culture—

"I think that the first step would be to put in place the principle that local authorities are mandated to plan for culture and for them to articulate their priorities. That has been the first step taken in other countries, including in France, where there is a requirement for authorities to have a cultural strategy to show how they are considering culture. We would then consider how Creative Scotland and other national bodies could collaborate to help to deliver that."iv

This approach has been embedded within the Irish funding model in which local authorities are required by statute to have an arts plan.xvi This statutory requirement is supported by framework agreements, as noted by Director Orlaith McBride when she gave evidence to the Committee—

"At the national level, there is the County and City Management Association for all local authorities in the country, of which there are 31. We have a memorandum of understanding at the highest level with that management association, and we have a framework agreement with every local authority at an individual level, which is signed by me and the chief executive—not the arts officer—of the local authority. The agreement is very much embedded in the local authority’s work."iv

This framework also provides a basis on which to determine respective responsibilities and priorities between local and national partners, as well as helping to identify opportunities for local and national co-funding—

“There will be areas of responsibility that are really important at the local level that the Arts Council, as a national agency, might not be that interested in. There will also be particular programmes—for example, development initiatives such as work with older people or young people, or work in very rural or disadvantaged communities—that we are really interested in, because they align with our strategy, and we would co-fund them.”iv

The Irish example of local and national policy coordination highlights a wider trend in the Committee’s comparative research, which concluded that the strategic alignment of national and local government priorities is very important to the funding of the arts, noting that "countries do not consider national arts funding in isolation from local governance".xix

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that she would welcome a framework of understanding akin to the Irish model, noting "that is what we did with the public libraries national strategy".iv The Cabinet Secretary explained there are differences between the Irish and Scottish context, including the fact that the Irish framework has "…underpinning legislation [that] allows ministerial direction of local authorities in relation to culture, which we do not have." In the Cabinet Secretary’s view, "The political context of our relationship with local government is such that, at this time, I do not think that local authorities, or even some parties in the Parliament, would accept something as direct as a memorandum and framework."iv

The Committee considers that the existing policy framework for establishing the respective roles of local and national government in funding the arts, including opportunities for co-funding, is not working well. It notes the positive outcomes that have come from taking a more structured approach to intergovernmental working through the development of the public libraries national strategy.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should work in partnership with COSLA to create a new intergovernmental policy framework between local and national government to support the arts as part of its forthcoming culture strategy. The Committee recommends that the new framework should include a requirement for local authorities to plan for culture and to take account of local and national priorities in doing so.