Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee

Public Participation in the Scottish Parliament

Interim report – Public Participation in the Scottish Parliament

Background

The Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee (The Committee) was set up at the start of Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament.

The Committee's remit was extended in session 6 to include citizen participation and to consider and report on public policy or undertake post-legislative scrutiny, using deliberative democracy, Citizen's Assemblies or other forms of participative engagement.

The Public Participation Inquiry

In spring 2022, we launched an inquiry into how people's voices are heard in the work of the Parliament.

We want to hear from people across Scotland, especially when we are developing new laws or policies that affect them. This is important as we know that the Scottish Parliament doesn't hear from some groups or communities.

We want to ensure that the views and opinions of everyone in Scotland are included in the work of the Scottish Parliament.

Our inquiry started with us consulting with people across Scotland. This report sets out who we heard from and what they told us.

A citizens' panel of members of the public then considered the evidence and agreed several recommendations for action. These recommendations are included in this report and the report of the Panel is set out in full in Annexe B.

We are now asking which recommendations the Scottish Parliament should prioritise first and what action we need to take.

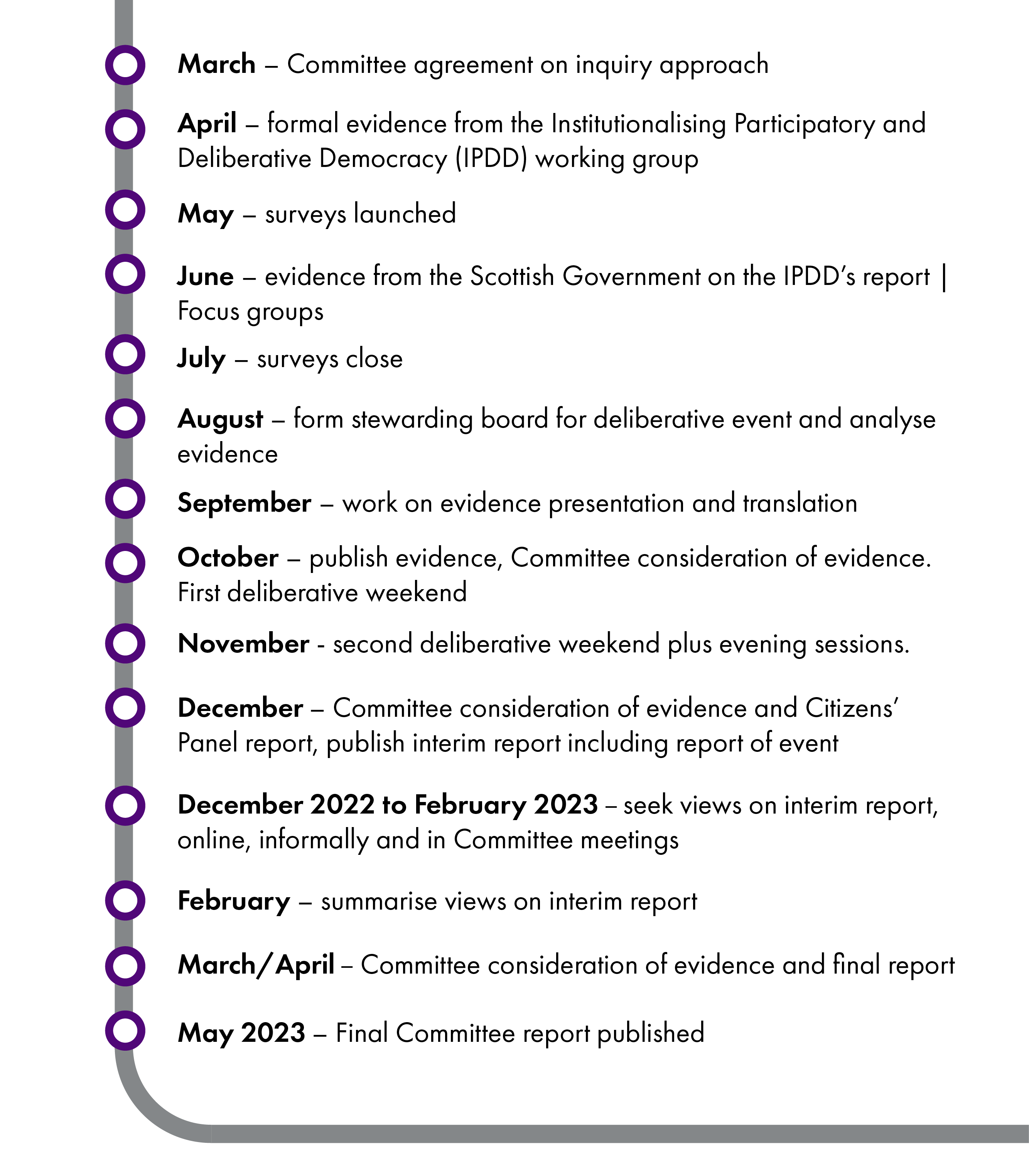

Timeline of the Inquiry

Who we heard from

The views shared in this report come from many different activities and represent the views of more than 460 people and organisations.

Between May and July 2022, we had an open public survey. This received 305 responses from people of all ages from across Scotland, covering 25 local authorities. Around 17 per cent of these people said they had never been involved in the work of the Scottish Parliament before.

We shared the survey in various languages and invited people to submit in the language they felt most comfortable using. We had one response in Polish, one person used Gaelic, and four responses were from British Sign Language (BSL) users.

We also had a survey that looked for more detail on increasing engagement. That had 35 responses from various organisations and individuals, including academics.

We heard from 119 people in 10 focus group sessions. People from many places and backgrounds spoke to us, including people from minority ethnic and migrant backgrounds, people with physical and learning disabilities, people from low-income backgrounds, and people living in rural and island locations. We also invited people to send us submissions by email, and four people/organisations did this.

What people told us

Although people with protected characteristics are under-represented in the work of the Scottish Parliament, people said those with a low income are most likely to be under-represented.

People from disadvantaged backgrounds don't feel that engaging with the Scottish Parliament is worthwhile. People often struggle to engage in the work of the Scottish Parliament as they don't feel representatives reflect them, or their communities’ needs and concerns.

Education has a vital role to play in breaking down barriers to participation in the democratic process.

Cross-party groups are integral to the involvement of minority groups and those with protected characteristics in the work of the Scottish Parliament. Cross-party groups are groups of Members of the Scottish Parliament and other people interested in a subject or issue.

The Scottish Parliament needs to do more to tell people about its engagement and participation work, as those we reach are positive about the experience.

Strengthening trust in politics and politicians is essential to successfully involve people in the work of the Scottish Parliament.

Breaking down barriers to participation will improve the diversity of participation and opinions in the work of the Scottish Parliament.

We knew that certain types of people, who are protected by the Equality Act 2010, might be less likely to speak to the Scottish Parliament – people from ethnic minorities, with disabilities, or who might be discriminated against because of their age, sex/gender, religion, or sexuality.

People also told us that many people who aren't protected might not speak to us. These included people on low incomes, who are unemployed, who live in rural areas, who didn't go to university, or who don't have English as their first language, among others.

Intersectionality

Many people said if people have more than one of these characteristics, that might mean they're less likely to speak to us, and they may be even less likely to engage. That was the same for people who might have more than one barrier to engagement.

Barriers to engagement

Barriers to engagement

People told us there are many barriers to engagement. These are mainly:

Money: People linked money and income closely to education levels, employment status, time, and age. If you have more money, you may find it easier to overcome other barriers.

Time: This is linked to money when it comes to employment types and childcare, but people also said if they were very busy, they had to feel taking part was worth their time.

Incentive: People need an incentive to take part – to feel like it's worth it. To do this they need to trust us and the process. Having more education might mean you understand your role more, but some people also thought well-off people might feel their voice is more likely to be heard.

Education: People need to understand political systems to see where they fit in and to know how to be involved. This starts at school. Many people said that they didn't know what the Parliament does for them and said that our language is intimidating. Politicians and Parliament staff need to learn more about the types of people they are engaging with.

Trust: Many people have lost trust in politics and politicians because they don't feel heard or represented. The media plays a part, but some people have engaged with us and not seen their voice impact on policy, so they have lost trust.

Fear/Intimidation: People need to feel safe taking part and not at risk of intimidation or bullying (including online). Some people aren't comfortable in a 'formal' environment.

Representation: People will trust us more if they see more people like themselves represented in our work – people from minority groups, but also people from low-income or deprived backgrounds, people from rural areas, and children/young people. We could tell people more about our work with these groups.

Resource: People thought more resource was needed to tackle all the other barriers. This means more time and money to help people to be involved and have their voices heard. This could be targeted at education, support services and the voluntary sector, and at the Parliament's engagement services, for instance, helping to cover people's costs when they participate.

Citizens’ Panel Recommendations

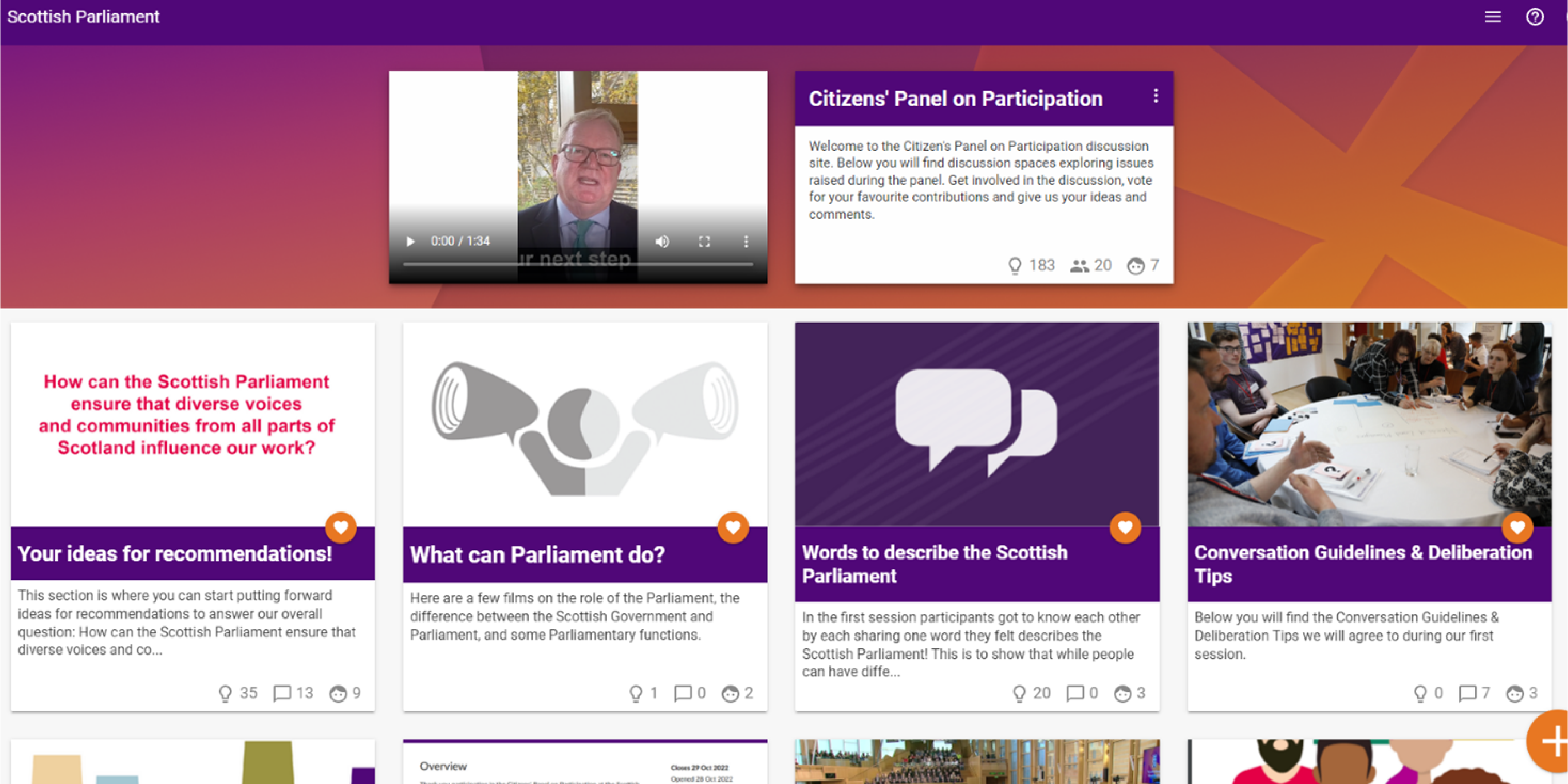

The evidence the Committee received was shared with a panel of 19 randomly selected and broadly representative citizens considered the question:

How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?

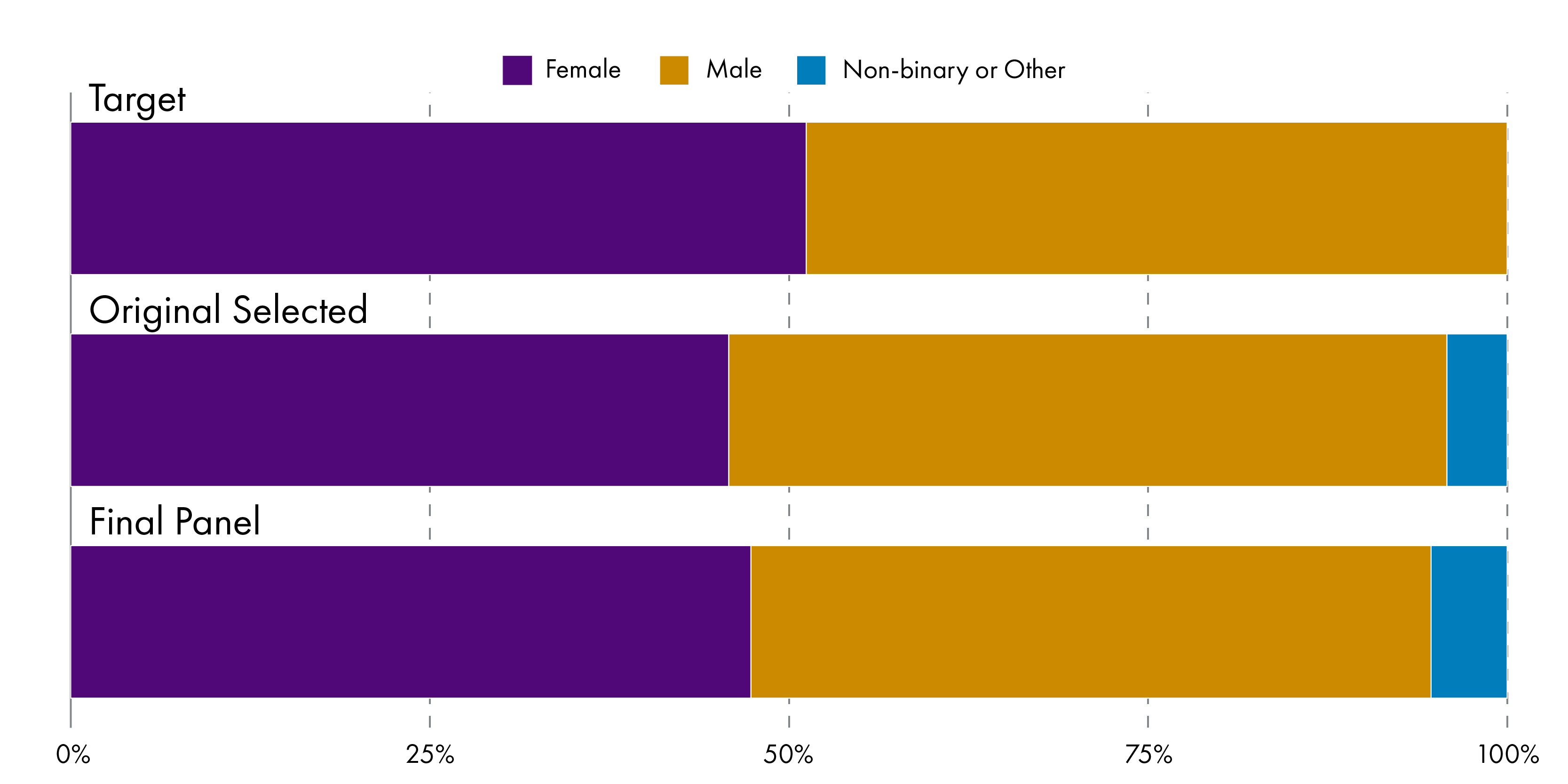

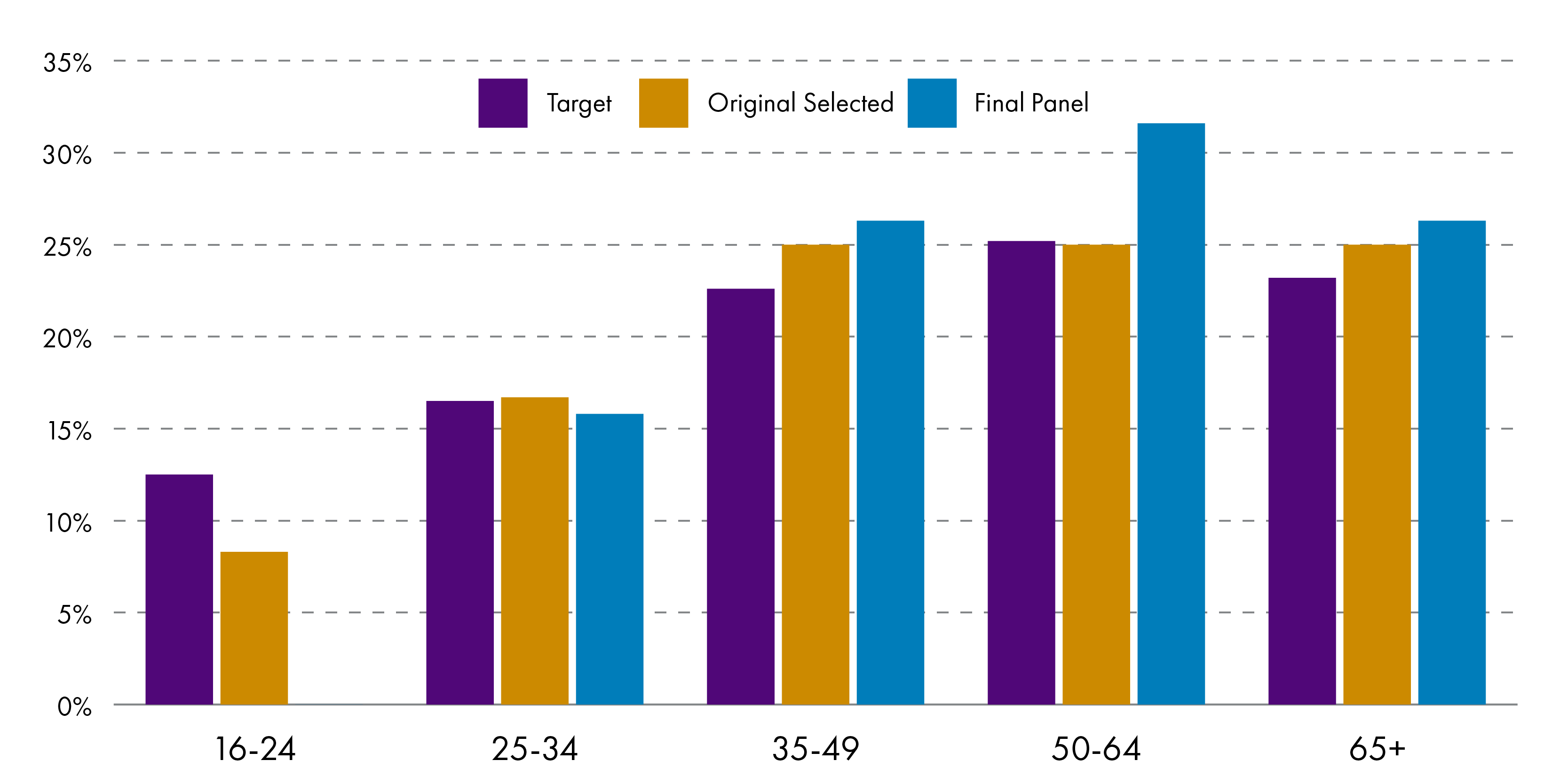

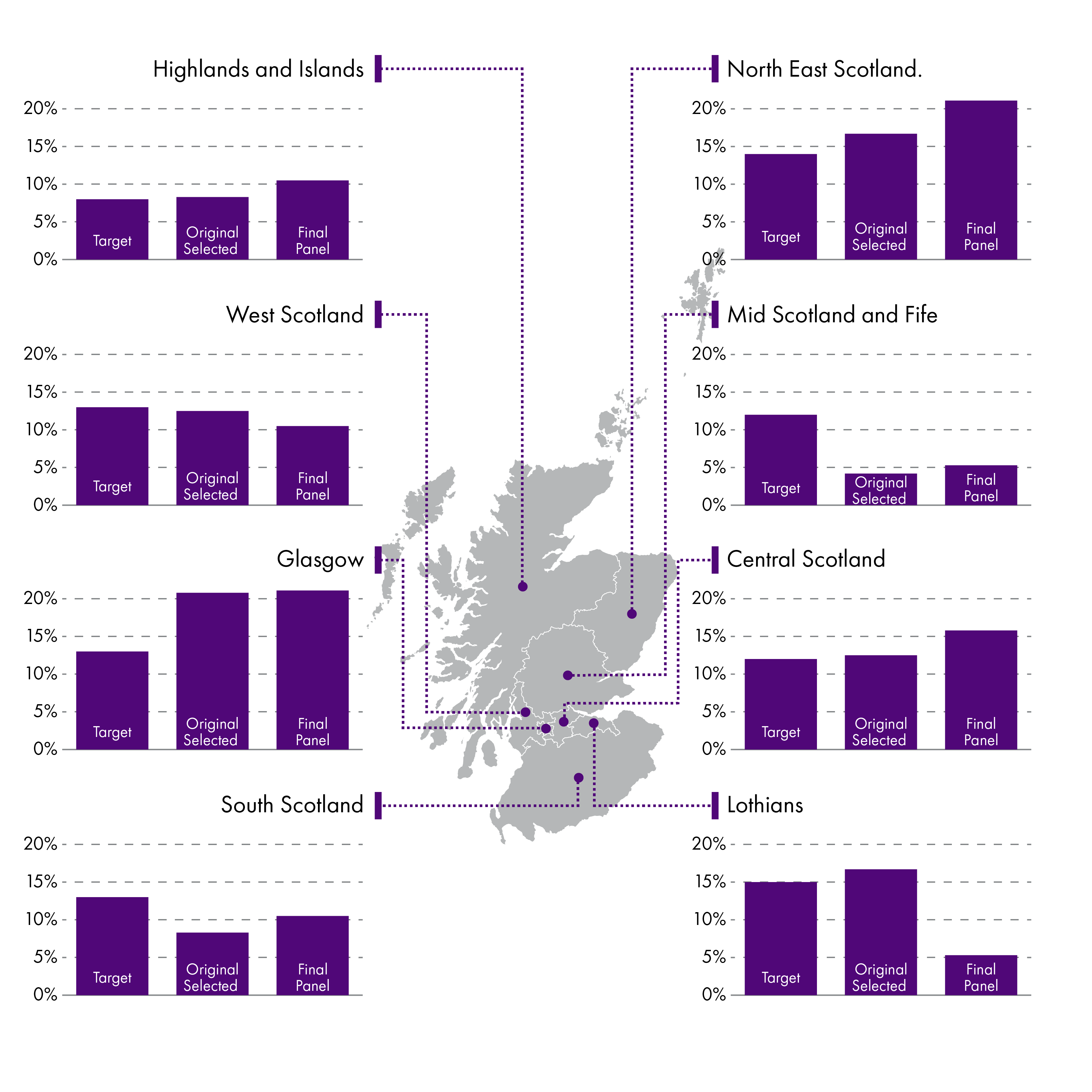

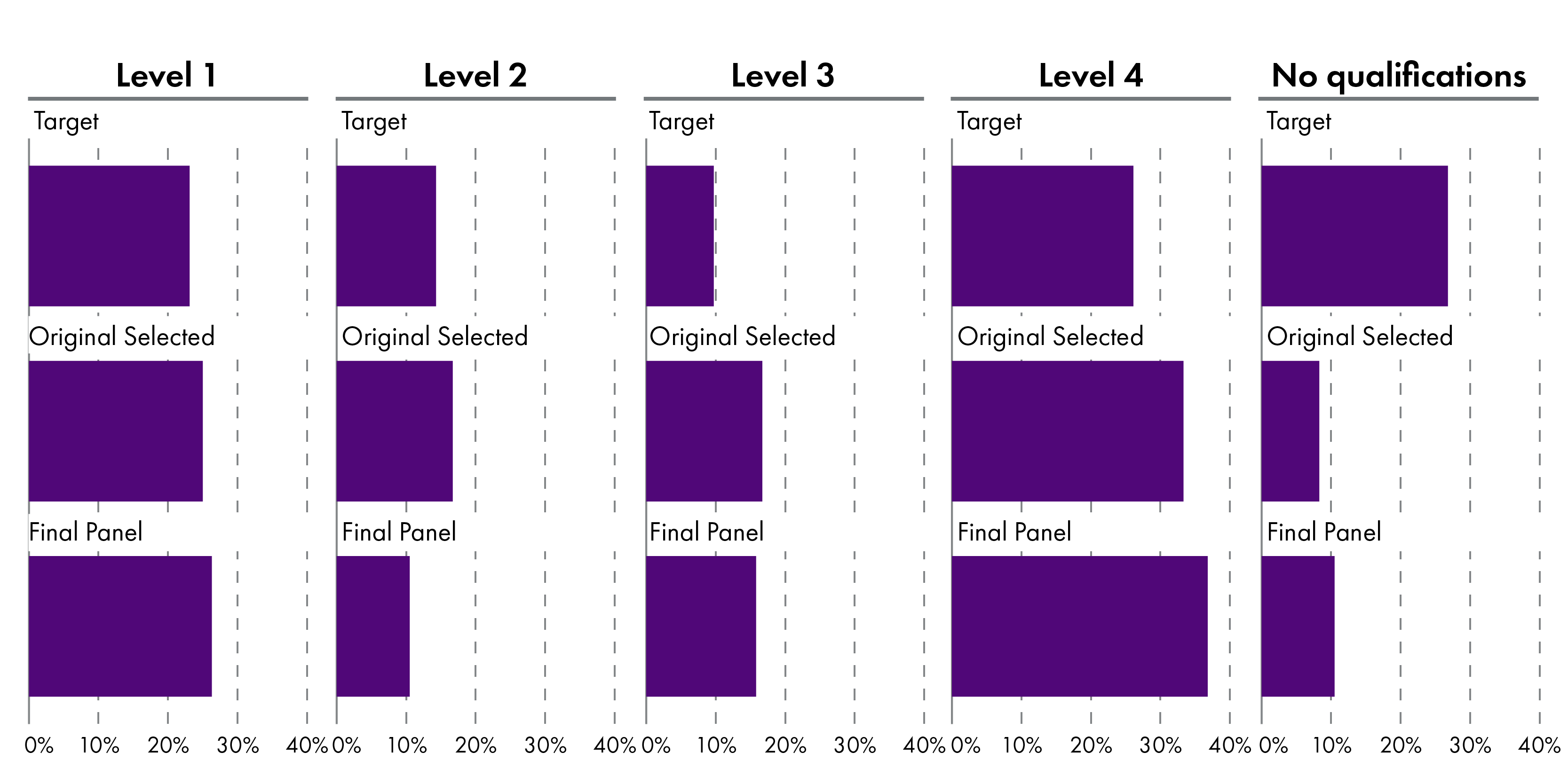

The Citizens' Panel on Participation ("the Panel") was selected via random stratified sampling based on 159 responses to 4,800 invitations sent in August 2022.

The Panel, which was broadly representative in terms of gender, age, location, ethnicity, disability and educational attainment, worked together for over 32 hours during two weekends and three remote online sessions in October and November 2022.

The Panel process included team building; learning about the Scottish Parliament, participation and deliberative democracy; questioning witnesses; deliberation and consensus-based decision-making.

The Panel were able to hear from a wide range of evidence and were able to request evidence sessions to ensure they received as much information as possible to help them answer the question.

As a result, the Panel heard evidence from Scottish Parliament staff; MSPs; members of the public who have experienced barriers to participation; political scientists and academics; deliberative and participative democracy practitioners; journalists; and a wide range of community organisations.

By the end of the deliberative process the Panel identified four broad areas and seventeen recommendations to improve how we engage with the people of Scotland. Annexe B sets out the full report of the Citizens' Panel. The Panel's recommendations are summarised below and grouped into four areas:

Community Engagement

How the Parliament uses Deliberative Democracy

Public involvement in Parliamentary business

Communication and Education

Community Engagement

1. Remove barriers to participation so that everyone has an equal opportunity to be involved in the work of the Parliament.

Follow up on previous research by researching different methods of engagement, who they work for, and the resource that is needed to use these methods.

Apply research to use different engagement methods to reach the whole of society, including non-digital and digital approaches.

Be mindful of solutions to reach all parts of society - work together with people to identify and create appropriate engagement methods for start to finish inclusion. Innovations like citizens' panels are good but be careful for how costly they are and how they may not engage people with other responsibilities or concerns such as child caring responsibilities, those on low incomes, those who don't have flexibility around work. Have an active approach to seeking out alternative voices and ensuring opportunities to engage are as flexible and as varied as possible: when, how and where people feel comfortable.

Raise awareness that the Scottish Parliament will provide payment which addresses the cost barriers that people face when coming to the Parliament and taking part in engagement activities, such as travel expenses, lost income from time off work, childcare and additional costs related to accessibility requirements.

This could also be expanded so that experts or individuals representing already identified protected groups or minority communities could be paid for a couple of days a month to work with different teams. Paying for engagement isn't enough to make it effective though – training and education are crucial to make community engage effectively.

Ensure access for people with English as a second language including promoting and improving use of Happy to Translatei. Support participation from those with learning disabilities by promoting and increasing the of Easy Read.

2. Create opportunities for people to use and share their lived experience to engage on issues that they care about.

We heard that people are effective at being experts on things and can upskill and educate themselves very quickly if they need to - COVID-19 proved that. We don't have the bandwidth to feel passionate about everything all the time – but when we do we need to have the channels there to engage.

When identifying witnesses, ensure an even balance between academic and professional experts, and people with lived experience.

Experts by experience panels can be empowered by the process because they are treated as equal and the group can bond and build empathy. Committees could also build communities of practice embedded in communities across Scotland (e.g. farmers group, disability awareness and support groups) to work with members and Parliamentary staff.

3. Raise awareness of Parliamentary business in plain and transparent language including visual media

Core principle: Use clear and direct language and visuals to communicate information about parliament, including legislation.

Undertake research into the general public's level of trust and knowledge about the everyday work of the Scottish Parliament.

How many people are actually satisfied with their dealings with their representatives compared to those who are dissatisfied? What level of understanding do the public have around the difference between Parliament and Government? If people knew that Parliament was an independent institution here to represent the people of Scotland, pass laws and hold the Government and public bodies to account, they would be more likely to engage.

4. Bring the Parliament to the people.

The Parliament should test approaches to using regional engagement/information hubs and/or a travelling exhibition or mobile unit.

The Parliament should go to where people already are and where they feel safe and have a sense of community and support; and talk to people about their issues rather than politics. We would like to see the Parliament testing the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of:

displays in public spaces where people are informed of the topical debates affecting their community and are able to communicate their views simply. These could be in schools, libraries, art galleries, community centres, shopping centres and parks;

Information hubs in towns across Scotland; and,

A mobile “Parliament bus” to make the Parliament visible in small or rural communities, where the public can share views, learn, ask questions, etc.

5. Ensure that community engagement by MSPs doesn't exclude people that are outwith community groups, including by using evenings, weekends and online services.

6. Create a system such as a webpage where people can register and be notified about opportunities to engage.

The Parliament should create and advertise means for people to register their details and interests with the Parliament. MSPs and Committees would be able to contact individuals about opportunities to engage in the work of Parliament when an issue arises that individuals are interested in. This idea was inspired by the amount of issues discussed at parliament at any one time passing the public by - this solution could ensure that no one misses the chance to engage.

How the Parliament uses Deliberative Democracy

7. Legislate for Deliberative Democracy in order to ensure that:

diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence Scottish Parliament's work, and

the public are consistently informed and consulted on local and national issues.

In drawing up this legislation the Parliament should:

Recognise that there is not one engagement solution that fits all situations and issues.

Design and implement a framework based on this panel's recommendations for ensuring diverse participation in deliberative democracy.

The framework should include:

An annually recurring citizens’ panel with agenda-setting powers to determine which local and national issues require either national or local people's panels (e.g., ‘deliberative town halls’).

Protection for participants to improve participation. We do not agree that participation in panels should be mandatory, but protective elements such as the right to time off work should be included for people who are selected to take part.

Rules around how MSPs consider and respond to recommendations from people's panels such as mandatory follow-up to people's panels’ recommendations no later than 9 months and a response from the Parliament and Government.

Potential for mixed MSP–people panels.

Ability to form local panels with local MSPs with outcomes that are sent up to the national level.

8. Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact

9. Build cross-party support for deliberative democracy as this is needed for it to work

10. We recommend that one of the panels which should be set up is a specific people's paneli to discuss the MSPs' code of conduct

Public involvement in Parliamentary business

11. Carry out a cost-benefit analysis of the Parliament itself or committees meeting outside of Holyrood and compare this to (a) more support and targeted invitations for people to come to Holyrood and (b) reinstating Parliament days (MSPs going out into communities for a day of activity).

12. Set a 9-month deadline as a default for feedback on the outcome of any engagement with clear reasons where this deadline would not be met (if applicable). The live status of the decision making process should be clear and transparent throughout.

Parliament could create a minimum standard of response. For example:

initial acknowledgement of engagement;

follow up to explain how many responses and what happens next;

a follow up with information on the outcome of the inquiry;

signposting with more information;

traffic light system for inquiries flagging up what has been addressed and what hasn't; and,

Monitoring calls logged and establishing rules as to how long someone would have to wait for a response.

This would show people that their participation is worthwhile and make people feel that their voice is being heard. Legislation and inquires can take a long time, so set expectations and from the start and consider how you will keep people involved in the longer term. If you don't do this it will fuel apathy and mistrust.

13. Give the Presiding Officer the power to compel MSPs to give an answer to all questions asked: that is, a direct reply that is relevant to the question. This should include a process for a deferred answer if an immediate answer cannot be given. This will improve public trust and engagement.

14. Schedule specific time in the debating Chamber for individual public questions to be asked.

We recognise that there would need to be a process to filter questions and ensure they were relevant and to determine who asked the questions and how.

Communication and Education

15. Use media outlets, documentaries and short films to highlight Parliament successes and real life stories of engagement to improve public perception and trust.

We heard that the Scottish Parliament needs to do more to tell people about its engagement and participation work, as those it reaches are positive about the experience. Then it is a matter of finding the best marketing practices to reach as many people as possible.

Use people who have had positive interaction and experience with Parliament to tell their story through national and local media (TV/radio/newspaper etc.) and community groups. The public sometimes find it easier to digest information by way of another person telling them. Make sure people know about the teams of staff working on engagement as well as MSPs.

16. The Parliament should run a general information campaign explaining the role of the Scottish Parliament – a single brochure or leaflet explaining who your local MSPs are, what a call for views is and the role of the Parliamentary service and its impartiality and separateness from Government.

All age ranges may need more information on what the Parliament does and what it can do for them. We think this is something that could be done quickly.

17. The Parliament should hold an inquiry into the relationship between the aims of the current curriculum and the Parliament to explore systematic changes that can be made throughout schools and in communities to improve children and young people's knowledge and awareness of Parliament - and deliberative democracy - including through mentorships, internships and competitions.

Our vision is that by the Parliament's 25th anniversary there should be a clear plan in place so that by the Parliament's 30th anniversary, all young people of voting age have clear understanding and knowledge about engaging with Parliament and Government and all see engaging with Parliament as a normal aspect of everyday life.

Next steps

The next stage is to hear views on the recommendations of the Citizens' Panel. We are asking which recommendations the Parliament should prioritise and what action we need to take.

We are asking people to share their views on 'Your Priorities' on the Scottish Parliament website.

The Committee will also carry out further evidence taking and fact-finding through January to March 2023

At the end of the inquiry the Committee will suggest improvements that can be made, based on what people have told us. The Committee expects to produce a final report in May 2023.

Annexe A - SPICe summary of evidence

Public Participation at the Scottish Parliament - What people told us

Background and gathering views

Between May and July 2022, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee (“the Committee”) asked people to share their views on whether the Scottish Parliament’s work involves, reflects and meets the needs of the full range of communities it represents.

The Committee did this in a few different ways. It ran two different surveys. A short survey aimed to find out about the people who have or have not been involved in the Scottish Parliament’s work, and their experiences. A longer survey allowed people to share their views on what can be done to improve public participation in more detail. The Committee also held 10 focus group sessions, which gave people a chance to share their view directly with politicians. These groups were chosen because they included people who might be less likely to get involved in the Parliament’s work, which includes people from minority ethnic groups, people living on a low income and disabled people. The groups were facilitated by:

AboutDementia

Active Inquiry

Bridge End Farm House

TPAS

Regional Equalities Councils

Connecting Craigmillar Kurdish

Learning Disability Assembly

Connecting Craigmillar Syrian

All Highland and Island Disability

RNIB

The focus groups took on various formats, from facilitated small group discussions and informal chats, to using character development, role play and theatre to express feelings about the Scottish Parliament. The Committee also held some online drop-in sessions that were run at different times of day to ensure people had the opportunity to participate at times that worked for them. If they preferred, people were able to email or write to the Committee.

Summary approach

In this summary, compiled by the Scottish Parliament’s research service (SPICe), we have set out the key messages, learning prompts and suggested action points that people shared with us.

This is a little different from a traditional summary of evidence, where a summary of what people answered to each question is set out. The hope is that it will better reflect the issues, challenges and solutions that people spoke about in a clear and easy to understand way, and can be used for a range of audiences, including to feed back to the people who shared their views. Views and evidence have still been attributed, but not in every instance because there were a lot of points that were made by many people.

By breaking views down into messages and actions, we hope that the summary process will feel less academic, and more democratic.

This approach also reflects the fact that this is an unusual scrutiny activity, in that it is to a great extent the Committee scrutinising the Scottish Parliament as a whole. There will undoubtedly be learning points and ideas here that will not only influence the Committee’s next steps and report, but will be used by the Parliamentary service

All of the responses that people asked to be made public will be published in full, and summaries from focus groups will also be shared alongside the published evidence.

Throughout this summary, researchers’ notes have been added in italics. The intention here is to add some context to the data provided, giving a more holistic picture.

Who took part?

Our detailed survey had 35 responses, which came from a fairly even mix of individuals and organisations. Those representing organisations were from mostly voluntary organisations supporting communities, and from non-profit organisations with a specialist focus on democratic participation. We also heard from a number of academics. Most of the individuals who took part identified themselves as having a specific interest or being part or a group that they felt was underrepresented in the democratic process.

305 people took part in the short survey. People who took part came from, across Scotland, covering 25 of Scotland’s 32 local authorities, and around 17% said that they had never been involved in the work of the Scottish Parliament before. Participants represented most age groups, from 13 years old to 65 or over (though most were 35 or older). We’ve explored some of the demographics of these participants in the next section, and have also published a separate summary dedicated to the results of this survey.

Overall, 119 people took part in our focus group sessions. These represented a broad range of individuals including those from minority ethnic and migrant backgrounds, those with physical and learning disabilities, those from low-income backgrounds, and those living in rural and island locations.

We also received 4 submissions sent directly to the Committee, which came from the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, People First, and Dr Danielle Beswick of the University of Birmingham.

We invited people to submit in the language they felt most comfortable with. On our surveys, we had one response in Polish, and four responses from BSL users.

All in, this summary covers the voices of over 460 individuals and organisations, from a diverse range of backgrounds.

Key messages

There were several key messages in the views people shared, which were often repeated and spread across the questions we asked.

Key message 1

The people who are under-represented in the work of the Scottish Parliament are more likely to be from lower income backgrounds than from protected groups

Protected characteristics

When asked to identify which groups are currently under-represented, the responses to our detailed survey were broad, and were very much replicated in the shorter survey. As might be expected, a number of groups mentioned belonged to groups with protected characteristics, as defined by The Equality Act 2010 and The Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties) (Scotland) Regulations 2012.

The Equality Act defines the following as protected characteristics:

age

disability

gender reassignment

marriage and civil partnership

pregnancy and maternity

race

religion or belief

sex

sexual orientation

Most of these characteristics were mentioned. Of these, people from ethic minority and migrant backgrounds, people with disabilities (physical and learning, along with mental health problems and the neurodivergent), and children and young people were mentioned/selected the most. There was also several mentions of women and older people, which was reflected most strongly in the short survey responses.

Transgendered people were mentioned in one response to the detailed survey, but not as an under-represented group. Rather, it was suggested in the context of women's rights that Trans people have their own spaces. There was similarly a suggestion of a trade-off between supporting Trans people, and supporting women, in the short survey. One person replying to the detailed survey felt that straight, white (specifically Anglo-Saxon), Protestant males are under-represented, and there were several responses to the short survey also suggesting men were under-represented. There were no other mentions in the detailed survey of people being under-represented because of their sexual orientation, or their religion/beliefs. Although there was more mention of these characteristics in the short survey, they were still lesser cited characteristics. There were a handful of statements in response to the short survey that suggested that some people in majority groups feel they are ignored in favour of minority groups (but statements contradictory to this were far more common).

Those not covered by equalities legislation

Moving away from the protected characteristics, people on lower incomes, and those with lower educational attainment and lower literacy were the most mentioned across both surveys. This covered both unemployed people, and people who were employed in low-income jobs and likely to have a lack of ability to take time out of work. Those with caring responsibilities, and young parents, were also mentioned as being 'time poor'.

Rural and island residents, and even non-Central Belt residents, were seen as being less likely to attend the Parliament and its events because of geographical barriers (especially around transport time and cost). Although there was a lot of support for digital and hybrid working, people highlighted that many people are digitally excluded (because of skill/education, and money), with ties made to age group and social media use. Age Scotland gave a good overview—

“In Scotland, around 500,000 over 50s do not have access to the internet and up to 600,000 over 50s do not have a smart phone. The reasons behind not being online will vary from person to person, and for some this will be a deliberate choice. However, for others, it may be due to living in an area with poor connectivity, because they feel they don't have the confidence or skills needed, or because they cannot afford the necessary equipment or cost of a broadband connection. According to the Scottish Household Survey, older people in the ‘most deprived’ areas are less likely to use the internet than in the ‘least deprived’ areas – and this gap may widen as the cost of living rises and people cut back on spending. Evidence shows that disabled people are more likely to face digital exclusion. Ethnic minority older people are also at risk of digital exclusion due to language barriers, affordability concerns, or finding new learning challenging.”

Some of the groups mentioned could be seen to some extent as self-selecting - non-voters, people who do not use Scottish-based media, and those with less confidence in the topics discussed. However, it's likely that many of these people are in fact affected by the issues above, making their participation less likely - educational attainment, language, income, and disability could all play a part in people's options and decisions.

In the focus groups held, we heard from a diverse range of audiences who did not usually confirm their economic status, however based on the geographic locations and communities we spoke to it's likely that many of the participants in the focus groups were from less affluent backgrounds.

Many submissions highlighted that intersectional individuals, i.e. ones with more than one of the characteristics or circumstances mentioned above, will be even more likely to be under-represented. Specifically, people from ethnic minorities on low incomes, disabled people living north of the Central Belt, migrants with mental health support needs, and young people with learning disabilities were among those mentioned. It was also suggested that people who don't belong to a community or a specific group can be hard to reach.

Finally, there was some mention of people grouped by profession – members of the police force, teaching staff, and veterans were all mentioned as people with whom the Scottish Parliament should be connecting with more.

Contradictions and discussion points

In the shorter survey, we asked people to identify groups/types of people who might be more or less likely to be involved in the work of the Scottish Parliament, using opposing questions with the same list of possible responses. Because the same list for both was used, we essentially asked the same question in different ways, capturing a more nuanced scale of opinion.

The five groups considered the most likely to be involved, starting with the option with the highest number of respondents and working down, were 'people with a high income', 'older people', 'people of working age', 'men', and 'people from LGBTQ+ communities'. When people were asked the opposing question, the responses suggested a similar set of groups, but with 'people on average incomes' replacing 'older people'.

Those groups most rated to be least likely to be involved, were 'people on a low income', 'people with learning disabilities', 'children and young people', 'people who are neurodiverse (e.g. With autism, ADHD etc.)', and 'people from minority ethnic backgrounds'. Again, when we asked the opposing question, the results were similar, but 'children and young people' and 'people from minority ethnic backgrounds' were replaced by 'people with physical differences' and 'women'.

Across both questions, women were equally rated as more likely and less likely to engage, which demonstrates a diversity of views. Looking at ratings and comments together, there are contradictory beliefs about certain groups – many people suggested that older people are more likely to engage because they have time, but many others said they are an overlooked group. There are similar views on young people. People of working age were seen as likely to be one of the more involved groups, yet one of the most cited barriers to participation was having time around work commitments. People from minority ethnic backgrounds were seen as less likely to be involved (because of language, cultural barriers, and exclusion), but conversely many people felt that more had been done to seek the voices of these groups than of other groups. It is very clear from the more detailed comments people left that there is a feeling that people who are part of groups which have the support of the voluntary sector and lobbying groups, and strong communities, may be the groups most likely to be involved because of the support structures they benefit from.

Overwhelmingly though, across all evidence, there was a strong consensus that people who have a socio-economic and educational disadvantage were the least likely to be involved in the work of the parliament, and the wealthier, higher educated were more likely to be involved. The transcending factor that people felt broke this barrier is having a specific cause or interest, access to organised support, and an interest in, or at least knowledge of, politics.

Demographics of respondents

Because this was an opportunity for people to be involved in the work of the Scottish Parliament, and a self-selecting exercise, it's interesting to look at the demographic information people gave us. Put simply, whether the people who got involved in our short survey matched the profile of those we might have expected, based on who people told us would engage the most.

Note that we did not include demographic questions in the detailed survey as this was where we expected more people to be responding on behalf of organisations. Interestingly, this meant that people responding to that survey were generally citing research or evidence (or indeed choosing not to answer because their expertise did not lie within the Scottish Parliament's activities specifically), and in most cases citing a range of demographic groups. The people who responded to the short survey were individuals, and only around a quarter identified themselves as having never been involved in the work of the Scottish Parliament. This may or may not mean that they cited their own characteristics when naming groups more or less likely to be involved.

The largest group of people who responded were aged over 65, and over two-thirds of the people who took part were over 55. There were far fewer people aged 34 and under, and only a handful of children and young people took part.

Over half of the people who took part did not consider themselves to be on a low income, and the majority identified as White, and Scottish or Other British.

Religion was not mentioned much in comments, which may reflect the fact that the greater proportion of respondents identified as belonging to no religion or belief system than any other specific grouping.

Again, as per what people told us, we had a lower number of responses from people with learning disabilities, physical disabilities and neurodivergencies than people who said they had a long-term illness/condition, or no illness or disability.

All these demographics reflect what people told us about those who were more or less likely to be involved in the Parliament's work.

However, far more women than men took part. There was also a far greater number of respondents who identified as heterosexual than LGBTQ+, and only a very small number of respondents identified as transgender. This contradicts many of the views expressed in both surveys. However, it may well be the case that topical issues (see Researchers Note below) and organised campaigns connected to these issues influenced the self-selecting demographic that took part.

RESEARCHERS NOTE: It's clear that, as with any survey, people will respond citing issues that are currently of high political and media interest. Although there are multiple comments which relate to a wide range of current discussion points (immigration, the war in Ukraine, UKG policy, isolated reporting on politicians, and wider ‘scandals’), there is one topic which stood out for the high number of comments. Matters pertaining to gender recognition, other LGBTQ+ issues, and the recent Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021 have all been cited more than any other grouping of issues, often with some of the more strongly worded statements. Accompanying comments centre around inappropriate power being given to lobbying groups, “politically correct” agendas pertaining to minority groups being pushed at the expense of the majority, and expressions of mistrust in politicians, political parties, political institutions and government. This context is important to note, because it adds some topicality to other categories – a high proportion of responses which identified women as under-represented also raised the issues above for example. This highlights the challenges of looking at any one point of data in isolation, and the need to be aware of wider social and political issues that will influence what people identify as key issues at any one point in time. Almost all the supplementary comments on each of the demographic questions “what is your sex” and ‘do you consider yourself to be transgender” argued in favour of gender being binary, and there were objections given to the ethnicity categories used (taken from the Census) based on the separation of ‘Scottish’ from ‘Other British’, which emphasises how topical issues can impact even on demographic questions. On demographics, it should also be noted that it will typically be the case that certain consultations will attract specific demographics because of those affected/interested. It is interesting to reflect that this is a consultation aimed at the Scottish population in the broadest sense, where no specific interest group has been targeted, yet the results may still have been skewed because of the timing of the consultation in relation to other, arguably unrelated, matters.

Key Message 2

People from disadvantaged backgrounds don't feel that engaging with the Scottish Parliament is worthwhile

What is overwhelmingly clear in the responses to both surveys is that people need to feel like their involvement has a purpose and is worth any sacrifice they may have to make to be involved. This could be an obvious sacrifice, like having to spend time and money to physically attend a meeting at the Scottish Parliament. But could also be far more subtle.

People spoke about the need to be clear about what would happen with people's views, and the extent to which they could influence outcomes and policy. This tied into timing – there was a clear suggestion that people would be more likely to participate if they knew it was at a stage in the consultation process where real change could be made. A lack of influence over the policies being debated was described by many as being 'tokenistic', and ultimately not worth people's time. The newDemocracy Foundation gave the example of work in Ireland, where "because of visibly successful projects (Eighth Amendment CA) response rates to random invitations now exceed 20% where 2-5% is more common elsewhere".

Age Scotland said "we sometimes encounter a sense of reluctance from older people to share their views as part of Government and parliamentary calls for views and scrutiny, as they feel that things "will not change" as a result. Those who have previously engaged tell us they find the lack of action, progress or change that follows frustrating – particularly if they have invested time and effort in sharing their views. Others feel that efforts to engage merely go over the same ground when the main issues at hand have not changed.".

People First (Scotland) said "We have spoken a lot about the difficulties that people with a learning disability face; politicians tell us they are doing something about, they tell us they listen to us but nothing much has changed.".

In our focus groups, themes were similar. A participant in the Active Inquiry session spoke of apathy, disenfranchisement and feeling ignored leading to feelings of depression and no desire to engage.

Some of the other ‘costs’ and barriers to taking part identified (in Involve's response) included:

Being overburdened with other life responsibilities. Participants in our focus group with the Syrian community spoke about the pressure of personal life matters, such as family/financial demands. Others spoke of having little time for anything beyond working.

Fear of reprisals for speaking out - including for those with precarious lives. This could include people being afraid to lose their tenancy if they speak out on housing issues, or people being afraid of losing their job.

Fear of threats and harassment on social media for publicly sharing opinions.

Feeling intimidated by the building and the official status of the Parliament.

Because there is nothing in it for them.

An inability to focus on issues, though lack of interest, a feeling of relevance, or through neurodivergence (ADHD was mentioned).

A lack of budget available to mitigate challenges like translation, respite, travel support etc. was also mentioned in focus groups.

People don't know what route to take to get involved, and at the focus groups in particular people spoke about the challenges of just understanding how to get in touch with their MSP for support, let alone being involved in wider parliamentary work.

Key Message 3

People often struggle to engage in the work of the Scottish Parliament as they don't feel representatives reflect them, or their communities needs and concerns

This was a common theme, both in the detailed survey and the short survey. Respondents spoke about not feeling represented on various levels – by MSPs, by government ministers, and by the staff they encountered from the parliamentary service. This connected with a notion of “hostility towards decision makers who seem remote and out of touch” (Involve).

CRER included some statistics on the diversity of MSPs and the Scottish Parliamentary service—

"Although the last Parliamentary election led to six MSPs of BME origin, all are of South Asian descent, leaving many minority communities in Scotland still unable to see people of their own ethnicity represented in elected positions. This under-representation is not limited to elected office – the data that is available still shows an under-representation of parliamentary staff who list their ethnicity as 'minority ethnic' and the SP Diversity Monitoring Report for 2020/21 does not provide ethnicity breakdown by grade (although a gender split by grade is provided). Perhaps more worrying, although the percentage of applications for positions in the Parliament from BME people was at an all-time high of 15%, the success rate for BME candidates to appointment was just 3%, compared to a success rate for White candidates of 10%, and the ethnicity pay gap increased year on year from 21.3% to 27.6%."

Interestingly, people also spoke about not seeing themselves represented within the people they see us engaging with – i.e., the people who give evidence to Committees. There is a perception (and evidence to support) that witnesses tend to be older, male, middle-class and university educated (Stephen Elstub, Newcastle University). As well as leading to people feeling that the Parliament 'isn't for them', it also gives the impression that the same voices are heard repeatedly, and that there is "little scope for fresh ideas" (Forth Valley Migrant Support).

Together argued that the voices of children and young people are under-represented and suggested that decision-makers can be "resistant to change" and that at times "adults can be unwilling to engage with children and young people directly". This often leads to a reliance on third-sector services to help children and young people to share their voices.

Media representation was also mentioned. One individual responding to the detailed survey highlighted that he rarely saw his local area (Dumfries and Galloway) featured in national TV news coverage, or his veterans’ organisation mentioned in Scottish Government news releases.

A key message from focus groups included the idea of the institution "expecting people to fit into the Parliament's environment and way of doing things". People said things like:

"I wouldn't even think of that. I wouldn't know where to go. But seems like a battle to be heard unless you were a big group or had lots of money."

"The only way I can see to get involved with the process is to be a part of a political party, you need connections. One lone person does not have the possibility of accessing, a committee. A general member of the public could not access a committee or get involved."

"Your impression is, it's a huge building that you feel you are not allowed to go in."

Key Message 4

Education has a vital role to play in breaking down barriers to participation in the democratic process

In noting the demographics least likely to participate, Involve, citing other research, said that “the most significant determinant of political engagement is education. In general, the more education someone has received the more likely they are to be politically active (Verba et al. 1995). These are universal dynamics to political engagement and representation and apply to the Scottish Parliament too (Cairney and McGarvey 2013).”. This notion was echoed across many responses.

newDemocracy said that most consultations are "dominated by the enraged and the articulate as they get the most benefit or have the most at stake", however the wider evidence would suggest that 'articulate' is the key word here.

Alan Renwick from the Constitution Unit at University College London pointed out that people feel they do not have the information needed to take part in democratic activities. This impacts on their self-confidence in stepping forward when opportunities arise – they may not feel they have anything useful to contribute. Involve said that a key barrier to participation was people "genuinely not knowing that there are options available to do so".

There were several suggestions that education goes both ways – decision-makers and the people that work with them need to understand more about the people they are engaging with, and different communication methods. Several responses spoke about the role of third parties in the engagement process, in particular voluntary organisations and support services. These services provide education and facilitation both ways – to those the Scottish Parliament wishes to engage with on the democratic process, and to the Members and staff of the Scottish Parliament on the needs of different groups. This is, however, resource intensive for the organisations, and the process of supported engagement requires additional time and resources from a parliamentary perspective as well. CRER suggested that there is a lack of expertise in race equality issues amongst some elected officials, saying "we believe increased racial literacy by MSPs could improve understanding and awareness, and, therefore, improve policy and scrutiny, and this in turn would lead to increased participation."

Many people spoke about a lack of education on the democratic process and how to be involved explicitly. They also spoke about how off-putting legal disclaimers and long meetings could be to people. In focus groups, people highlighted that even where politics is taught in school, it very much focuses on voting, and there is little learning about being involved in the democratic process between elections. That said, in the online focus group we ran there was a feeling that when somebody has an issue, they don't understand or particularly care about the differences between the Parliament and the government, they just want their problem solved and it is very unclear who they need to speak to about that when current methods are not sufficient.

RESEARCHERS NOTE: What was also reflected in responses was a potential lack of understanding on the role of the Scottish Parliament (and scope of the inquiry), the Scottish and UK Governments, and where and how political parties fit in to this process. Rather than discount submissions where people have used the opportunity to speak about their grievances with leadership, political figures, policies and matters outwith the scope of the inquiry, Committee and Parliament, these submissions can illustrate how a lack of political knowledge can impact even where people are engaging.

Key Message 5

Cross Party Groups are integral to the involvement of those in minority groups and with protected characteristics in the work of the Scottish Parliament

In many cases, when organisations representing, and individuals from, minority groups spoke about the involvement of these groups in Scottish Parliament work, they spoke about Cross-Party Groups (CPGs). This included during our focus groups,

We asked people about the different methods of engaging with the Scottish Parliament. CRER said "We would have liked interaction with the Scottish Parliament Website to be included in the means of people being involved, and also included should have been participation in Cross Party Groups."

They also explained that "Cross Party Groups have been a major point of contact with MSPs, certainly for many members of Black / Minority Ethnic communities. This is particularly the case for smaller Voluntary Sector or volunteer-led organisations. One of the main strengths of the CPG system is that it allows non-Parliamentary members to easily identify a selection of MSPs with a particular interest in their subject area who may be receptive to information or lobbying activities. The opportunity to engage with these members on a personal level is valuable, and the group setting makes this easier to arrange and more cohesive – non-Parliamentary members often wish to put forward similar issues for discussion and the group setting allows a wealth of knowledge and experience to be explored. This consultation is a missed opportunity to consider further how to make involvement via cross party groups more effective. Additionally, as an incidental benefit, CPGs can provide a useful introduction to lobbying for those with no previous experience and allow them to build practical knowledge of parliamentary issues and procedures through engagement with MSP members.".

People First (Scotland) also spoke about representation on CPGs but expressed concern about the move to online meetings because of the difficulty in people with learning disabilities feeling they are getting their point across this way. They also said that late-night meetings were harder to be involved in, long meetings needed to have more breaks, and papers needed to be provided in time to allow conversion to easy-read formats.

In focus groups, minority ethnic participants felt that cross-party groups could reach out to community groups to connect them to similar groups or relevant organisations, creating wider networks.

RESEARCHERS NOTE Because CPGs are established and managed outside of the Parliamentary service, this may be an area which could be seen as outside the scope of this inquiry. It's important to see the user's perspective though, where this distinction may not be clear. To a member of the public, going to a CPG or contacting their MSP about something IS engaging with the work of the Scottish Parliament. This raises a wider issue that may benefit from further exploration – how best to better connect engagement and participation work which takes place in these contexts with Parliamentary work?

Key Message 6

The Scottish Parliament needs to do more to tell people about its engagement and participation work, as those we reach are positive about the experience

Respondents gave examples of work that the Scottish Parliament had done, both from a participant perspective and more academic viewpoints, which had been good examples of participative democracy. There is evidence to suggest that some people feel very positively about the approaches used. Feedback on the work of the Parliament's Participation and Communities Team at the focus groups was very positive. Some people said that just being invited into the Parliament building or having MSPs and staff come out to talk to them at these events made them feel more connected. That said, when asked how connected they felt to the Scottish Parliament at the start of these sessions, on a scale of 1-10, over half of people asked gave scored at the lower end of the scale.

RESEARCHERS NOTE It would be useful for this question to be asked again during PACT's follow-up work with these groups to see if these sentiments have changed.

Together said "there have been several recent examples of promising practice" and gave the example of when the Equalities and Human Rights Committee examined the UNCRC (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill. With support from Together, members held numerous engagement sessions with children and young people, and Committee also produced a child-friendly consultation paper and resources to help children build their understanding of the issues.

They also cited the Equalities and Human Rights Committee's creation of a 'Meeting in a Box'.

The crucial thing to note in many of these examples is that they have been cited by people who were involved in the work or were/are in some way more cognisant of the engagement culture of the Parliament.

In the short survey, many people spoke about positive engagements with the Scottish Parliament – a warm welcome, enjoyable and informative tours, taking part in CPGs and attending Committee and Plenary meetings, and positive interactions with friendly and responsive MSPs and staff.

It's not possible, however, to consider these views without looking at the opposing views given, which were often from individuals (outwith interest or community groups), or people who had contributed and felt they had not been heard (see Key message 1).

Short survey respondents who had less positive experiences spoke about not receiving responses (from MSPs, and in relations to petitions), not seeing their submissions published, and feeling like they had no ability to influence decisions because the Committees and Scottish Government had already made up their mind.

RESEARCHERS NOTE It should be noted that a high proportion of people expressing that they hadn't been listened to or had been dismissed/ignored by MSPs referenced that this was in relation to the Gender Recognition Act.

There were some specific barriers highlighted related to the way the Scottish Parliament runs consultations. Together pointed out that many consultation exercises take place within a short timeframe and said that this was a barrier to engaging with children and young people in particular. People also spoke of finding it hard to find consultations on our web pages, and to find out the outcomes after the fact.

SCDC said that “Current opportunities to get involved such as petitions, cross-party groups and lobbying are relatively formal, complex and high-level. As such they are likely to be off putting for people from disadvantaged and marginalised communities who are often not as skilled and confident at navigating and making use of these opportunities. Opportunities to get involved in comfortable and informal ways, such as ‘conversation cafe’ type approaches should be made available.”

It also pointed out that although it's aware of the education and outreach work the Scottish Parliament does, there's very little information on this in the public domain.

Involve spoke about the 2017 Commission on Parliamentary Reform and the changes that followed, including the establishment of the Parliament's Committee Engagement Unit, and said:

"It would be helpful for the Parliament to commission an independent review of the impact of the recommendations that have been implemented, and the reasons for any lack of implementation. Not only would this provide valuable internal monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) as to what difference the implemented recommendations have made and what might still stand to be improved, it would also inform resourcing at a level that can actually make a difference and it would also prove useful for other legislatures considering wider public engagement."

Key Message 7

Strengthening trust is essential to successfully involving people in the work of the Scottish Parliament

Respondents made it clear that trust was an essential component in successfully involving people in the work of the Scottish Parliament. They told us this directly, and academics described the challenges, but it also came across less explicitly as people described their viewpoints and experiences. It relates to all the key messages above to one extent or another but given its prevalence it's important to emphasise and summarise some of the points made.

Key points include:

People feel a lack of trust when they do not see themselves represented in policy or by the people that make policy. More pertinently, when people see people represented who they feel are very different or even directly opposed to them represented, it can reduce trust even more. The examples given suggested this happens in two very different ways.

The first might be more expected - people on low-incomes with lower levels of educational attainment feeling disconnected when they perceive that it is people from mostly wealthy, academic backgrounds who are making policy decisions.

The second is more surprising – people who feel that minority groups, or different minority groups from the one they belong to, are more represented than they are. There were, for example, several people who expressed dislike or distaste at what they felt was an unfair prominence given to LGBTQ+ people.

People who have engaged with the Scottish Parliament, but do not feel their voice was heard, may lose trust and choose to not engage again. Again, this seems to happen for two reasons.

They may have contributed their voice to a single issue that was polarising (i.e., there was likely to be a 'winning' and a 'losing' side) and be unhappy with the outcome. This highlights a challenge for the Scottish Parliament and its participation specialists – how can trust and connection be maintained or restored with people who have had a negative experience, particularly when that negative experience was in this context?

The other situation was where people felt their voice hadn't been heard was later in the policy lifespan, i.e. well beyond the consultation stage. The Islands (Scotland) Act 2018 (which was subject to a lengthy and extensive consultation/outreach programme at the Bill stage) was cited by more than one respondent as an example of policy which had not achieved its aims, partly attributed to a lack of effective implementation, but also because of a wider need for decentralisation of power across all of Scotland's democratic institutions. This emphasises that events and factors outwith the Parliamentary consultation phase can impact people's feelings about the engagement they took part in. In focus groups, one person said that they felt there was no point in taking part if nothing changes as a result, or if policy is too complex for them to understand what had changed.

As noted, education around political structures leads to confusion about who is leading on engagement and consultation. This links to the example above, where a disappointment in the Scottish Government is also reflected in views towards the Scottish Parliament. This could reflect a lack of trust in the entire political system, but it could also reflect a lack of understanding about the differences between and role of each institution, particularly in the role of parliaments in scrutinising governments.

There was also a suggestion that a lack of engagement was symptomatic of a wider mistrust of and disengagement in politics. Age Scotland, having highlighted that research shows that older people tend to be less trusting of politicians than younger age groups, said that "While distrust in politicians is not within the Scottish Parliament's control to fix single-handedly, it is good to be aware of this as an issue affecting engagement levels.".

Jane Jones, the Scottish Parliament's first Public Participation Officer (appointed in 2004), said that there is "a growing narrative within the media, including social media, that politics is 'a waste of time' or that politicians are 'only out for themselves', a disaffection for politics and politicians which is very dangerous for our democracy. If people have taken time to give their views, in the hope it may influence change and feel nothing has happened as a result, they will be reluctant to try again and may well adopt such views".

The Electoral Reform Society Scotland said that "the contemporary system of representative democracy leaves too few opportunities for citizens to participate in the political process and people feel increasingly shut out from those in power and their institutions.". A number of people referenced other democratic bodies, including local authorities and community councils, as having a number of the same issues noted above, and there were a few voices in favour of widespread redesign of our current political system. Obviously, this goes well beyond the scope of influence of this inquiry, but it illustrates the scale of the barriers which some feel influence people's ability and desire to interact with the Scottish Parliament.

Key Message 8

Breaking down barriers to participation will improve the diversity of participation and opinions in the work of the Scottish Parliament

People were asked in the detailed survey how we will know we have been successful in overcoming barriers to participating in the Scottish Parliament's work. It's useful to look at the picture of success before exploring the suggested actions so outcomes can be kept in mind.

Overwhelmingly, people suggested that a more diverse set of voices and views would be a marker of success. This might be reflected (outside of the evidence itself) in positive feedback, but more pertinently in people feeling involved and reflected in policy.

A willingness for participants to stand behind their work and that of the Parliament was also seen as a measure of legitimacy. Participation levels should increase, as should public satisfaction with, and trust in, Scotland's democratic system (expressed in part through the media).

Digging deeper, linked to many of the issues of trust mentioned, people felt that success could be measured by policy being changed as a result of engagement, and some of the everyday challenges people face in life being addressed. One anonymous respondent said:

"If you have been successful, the people who have felt under-represented will feel appreciated, more content and happier in their everyday life. This is meant to have an effect on everybody in their care/around them which should improve everybody's health and well-being, everybody's mental health, and perhaps help them make better lifestyle choices."

Several people suggested that there should be a monitoring and evaluation framework for participatory exercises. Together said to do this "Scottish Parliament ought to: measure what has been achieved and why; set rights-based indicators which take into consideration different cultural, social, and economic contexts; and gather both qualitative and quantitative feedback and ideas of improvement from children and young people". The use of audits, academic evaluation and stakeholder boards as part of a monitoring framework was suggested.

Improvements in the Scottish Parliament's work were also mentioned as a marker of success. One individual said quite simply “You will have changed! You will work and behave differently. 'CBT' for politicians and civil servants at national (Holyrood) and local government level.”

The Democratic Society said:

"The clearest marker of success is that you feel a sense of continuous development in your engagement practice, and new groups are coming to you, seeking to be included in further developments. The Scottish Parliament's vision of being the national home for debate and deliberation is an essential anchor point for these conversations, but they need to be driven by engagement and inclusion inside and outside Holyrood."

Suggested actions

We asked people explicitly what the Scottish Parliament could do to make it easier for under-represented groups to be involved in the Parliament's work in our detailed survey, but suggestions were made throughout the surveys, so this section captures the entirety of comments on that theme.

These actions have been grouped by theme – some are things which could improve existing approaches, and some suggest wholly new models.

Overarchingly, Stephen Elstub (Newcastle University) said:

"Involvement in the work of Parliament can be made easier if it is CLEAR (Lowndes et al. 2006):

• Can do – that is, have the resources and knowledge to participate;

• Like to – that is, have a sense of attachment that reinforces participation;

• Enabled to – that is, are provided with the opportunity for participation;

• Asked to – that is, are mobilised by official bodies or voluntary groups;

• Responded to – that is, see evidence that their views have been considered"

Transparency, openness, purpose and incentive

Reflecting key messages 2 and 7, people highlighted the importance of making it clear to participants how their input would be used, and more specifically, THAT it would be used – basically, that the effort of their participation would be worthwhile.

newDemocracy said that "A simple way to execute this online (where only the crazed and desperate contribute with any expectation of impact) is to make a clear Authority promise that a subsequent citizens' assembly will prioritise 20 (for example) ideas for detailed response. The incentives for an online contribution now change considerably."

Alan Renwick explained that:

"At the Citizens’ Assembly on Democracy in the UK, 93% of members agreed with the recommendation:

'The results of deliberative processes like citizens’ assemblies that are initiated by government or parliament need to have an impact. When they are convened, there should be a guarantee that their results will be made public, their recommendations will receive a detailed response from the convening body, and they will be debated in parliament.'"

One individual said, "Parliament must be a hub for bringing together the widest possible range of civil society organisations that can contribute on a given issue -not just in terms of building legitimacy and good legislation but also to develop capacity for subsequent implementation.".

Long-term engagement was also seen as important, to support repeat engagement and build relationships. Methods such as SMS or app-enabled engagement, and 'gamified' engagement where the key opportunity of an event might lie beyond participation, and in something more connected to the participants (i.e. connecting with neighbours, enjoying a free lunch), were suggested.

Listening and respect

Linked to the above, but perhaps less explicit, was the importance of listening to and having respect for under-represented groups.

Women, children, people with disabilities and ethnic minorities were mentioned specifically as groups who should have their views treated respectfully. Participation should take place in a safe environment, and there should be a commitment to accountability by following up with participants.

People should be able to participate and share their voice in a way which is comfortable for them and using more creative approaches to suit the needs of certain communities, such as island communities, is important.

CRER felt it was important that events be held where MSPs could meet community members from under-represented groups in order to build relationships.

SCDC suggested that an equalities and human rights-focussed approach, such as the the National Standards for Community Engagement would be a good model to use in engagement and participation. SCDC also noted the benefits of providing mentoring and emotional support to those participating, saying:

"Experience panels are beneficial for participants in terms of building skills, knowledge, confidence and connections, but they can also be a daunting prospect as well as emotionally draining. People should be provided with continual support, ideally from peers or recognised support organisations who understand the needs of particular groups. Support should also be impartial so that participants feel they are able to raise any concerns or ask any questions."

One focus group participant said:

"The person – me – who is approaching the Parliament needs to feel that they are being listened to, heard, and being recognised as someone who matters. So, getting feedback counts as you are not a voice in the wilderness crying out to this big body where your views can get lost – you don't know where your views go unless you get feedback.2.

In the focus groups in particular many people's self-reported experience of ‘engaging with the Parliament’ was through engaging with their local MSPs. They spoke about not knowing whether their concerns had been listened to because they had no feedback, or received only standardised responses.

A handful of respondents said that it was important that the voices of individuals be given as much credence as those from organisations when considering evidence.

Marketing and education

The general feeling was that the Scottish Parliament has a significant role to play in actively promoting and encouraging a culture of participation. One anonymous respondent said that it was important to recognise and represent people with a visible difference in staffing, culture, policies and commitment to representation.

Related to a need to be open about the potential impacts of participation, was the suggestion that more should be done to market and champion instances where people have had their voice heard, particularly where it has led to a change in policy, or their idea being used. Specifically, newDemocracy said this should be done through the mainstream media. SCDC pointed out that the 'community outreach' pages that were a part of the former Scottish Parliament website had not been replicated on the new site and suggested this was a missed opportunity to promote the good outreach work done.

Jane Suiter of Dublin City University said that it was not enough just to include diverse voices in participatory approaches – other participants needed to be made aware of the importance of including these diverse voices. Sortition Foundation suggested that publicising the involvement and work of demographically diverse groups would help to normalise the involvement of those groups in the Scottish Parliament's work.

In focus groups, people spoke about language on two different levels. Both diversity of languages used to communicate, and the ability to understand the processes, procedures and reports being discussed and the "over-reliance on the written word". Essentially, to reach people we have to work in their language, be that in a non-English or accessible language, or simply making this less formal and easier to understand. People from minority ethnic and migrant backgrounds asked for more support to be given to help people coming to Scotland to learn English.

Those carrying out engagement and participation work should be trained and educated on the needs of specific groups, including marginalised and disadvantaged groups (for instance how best to engage and work with children), as well as in facilitation methods. Connected was the suggestion that well-resourced information and outreach work was important to support people to be involved in the Parliament's work, and that “Staff working with communities should be skilled in deliberative methods, human rights and equalities” (SCDC).

Educating people about their right to be heard and the importance of taking part was a common theme, linking into transparency and purpose. One participant at a focus group explained that as an migrant they had no knowledge at all on their democratic rights in Scotland. It was suggested by a few people that the Scottish Parliament website should be aimed at a wider audience (i.e., not just 'experts'). Jane Jones suggested that Open University courses on, and developed with, the Scottish Parliament, would be beneficial (with some emphasis on the need for these to be accessible to those on low incomes through bursaries funded by the Parliament).

Alan Renwick of UCL said:

"people need information. In part, that means information about the engagement processes in themselves: people need to know what they are being asked to do and what will be done with the inputs that they provide. But there is a wider point: people will view the prospect of participating in a specific engagement exercise as very effortful if they feel alienated from politics more broadly: they will feel they do not know enough and that it will be hard work to keep up. So improving education and information about politics is vital."

He went on to share findings from the Citizens’ Assembly on Democracy in the UK, which gave a very clear directive that in general, education on politics and democratic participation in the UK needs to be improved, and that many people feel ill-prepared by their formal education to engage with politics. It also found that most people feel that more needs to be done to make information on what is happening in Parliament and Government more accessible and available.

Accessibility

Simply increasing access to the democratic process was a common theme, with some people simply saying, ‘make it easier for people to be involved’.

The EHRC said that "Compliance with the Equality Act and, specifically, the Public Sector Equality Duty will integrate consideration of non-discrimination, equality and good relations into the day-to-day business of the Scottish Parliament.", and that "data on the experiences of people sharing different protected characteristics who participate in all engagement activities should be collected, disaggregated without identifying individuals, published and used to tackle under-representation issues.". It asserted that "ongoing monitoring of equality data will help to measure the success of suggested improvements".

Zoom and other online forums were mentioned as opportunities to increase attendance numbers, with people citing their experience of increased participant numbers when some activities moved online during the pandemic. Conversely though, it was emphasised that non-digital means of engagement should be protected and maintained, and that "people who do not have digital access must be able to follow parliamentary proceedings and be given the same opportunities to contribute" (Age Scotland).

The need to work with specific groups (and community groups) on designing services and activities was made clear – quite simply, asking groups what works for them and taking a collaborative approach. There was also mention of making sure accessibility measures to support people with barriers to engagement were taken, such as making sure information is provided in different language options and different formats, including easy read, audio, large print and Braille. Audit Scotland suggested that developing a presence within community groups may be beneficial.

CRER spoke about the need to be able to accept evidence beyond the submission of a formal written document. Formality was a common theme, with the suggestion that breaking this down with more informal meetings and optics (fewer suits and uniforms, and less hierarchy of voices for example) could help people to feel more comfortable.

Relevance was emphasised by Together, quoting work done by the UN committee in relation to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In order to make participation accessible for children, the issues being discussed should be relevant to children, and delivered in a child-friendly way.

Practical barriers to participation, such as being able to take time to attend meetings (especially around working and childcare commitments), being able to afford to attend meeting (in terms of travel and costs related to time barriers), and overcoming technological barriers, should be mitigated for. Many respondents felt that funding specifically targeted at these barriers was needed to help those on low incomes participate. Suggestions around this included compensating people for their time, giving extra support for those with caring responsibilities, paying travel costs up front where necessary, and offering training and equipment to those who might lack the necessary IT skills to fully participate.