Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland Bill

The Bill would introduce a new role of Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland. This is in response to the recommendation from the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. The Scottish Commissioner would look at systemic patient safety issues in the NHS and drive improvements in care. It would also promote the views of patients and the public in relation to the safety of healthcare.

Summary

The Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland Bill was introduced in response to the recommendation of the UK Government commissioned Cumberlege review of the hormonal pregnancy test Primodos, Sodium Valproate in pregnancy and transvaginal surgical mesh.

Each of these products was associated with significant patient harms and one of the main findings of the review was that patients were not listened to. The review therefore recommended the creation of a Patient Safety Commissioner (PSC) to listen to, and provide a voice for, patients with a view to driving systemic improvements in care. This was to be focused on medicines and medical devices.

Patient safety

Unsafe care is believed to be within the top 10 leading causes of death globally, resulting in over three million deaths each year. In developed countries, the direct cost of unsafe care is estimated to be around 13% of healthcare spending, which would equate to approximately £1.9 billion of spending in Scotland.

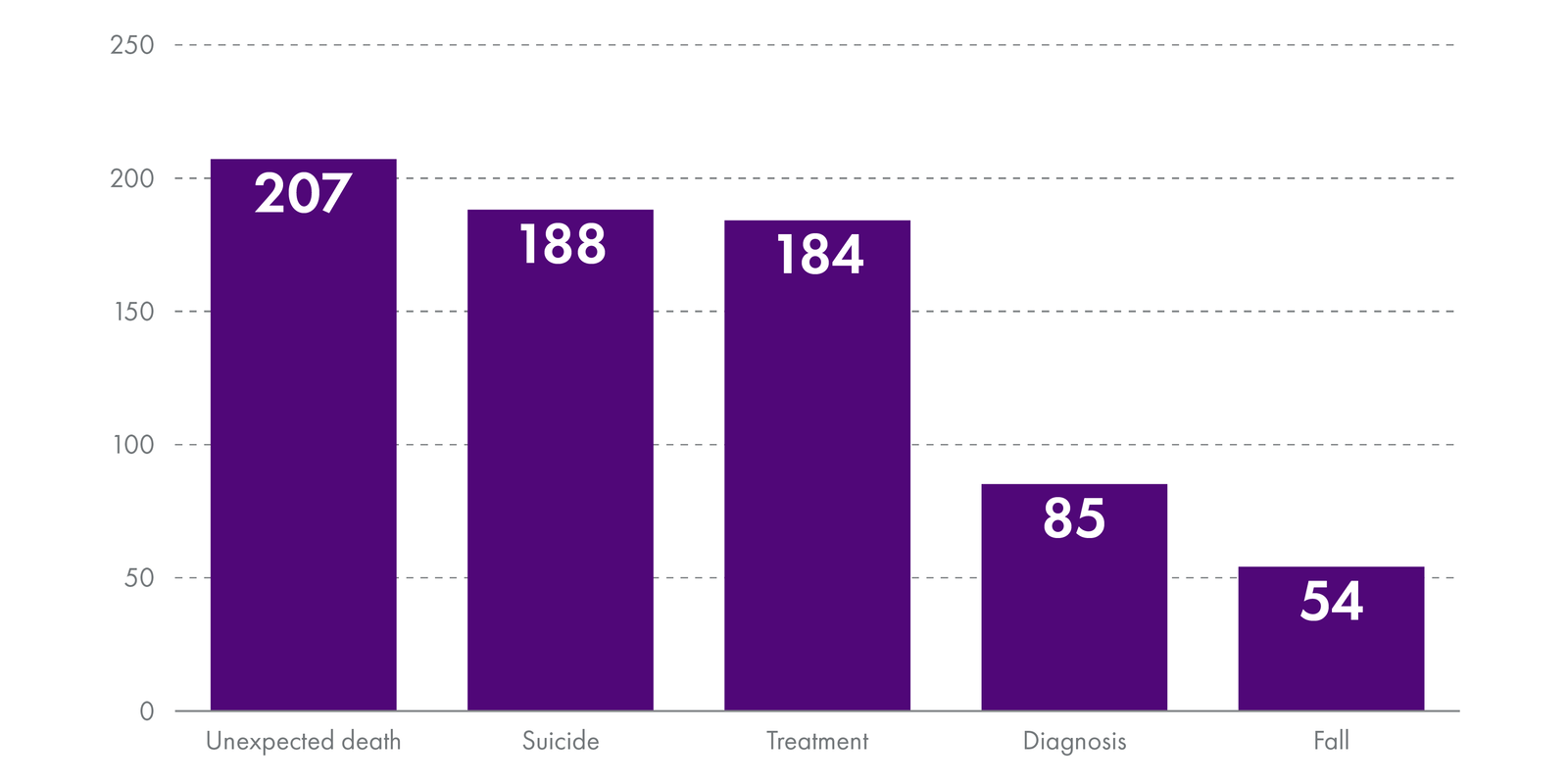

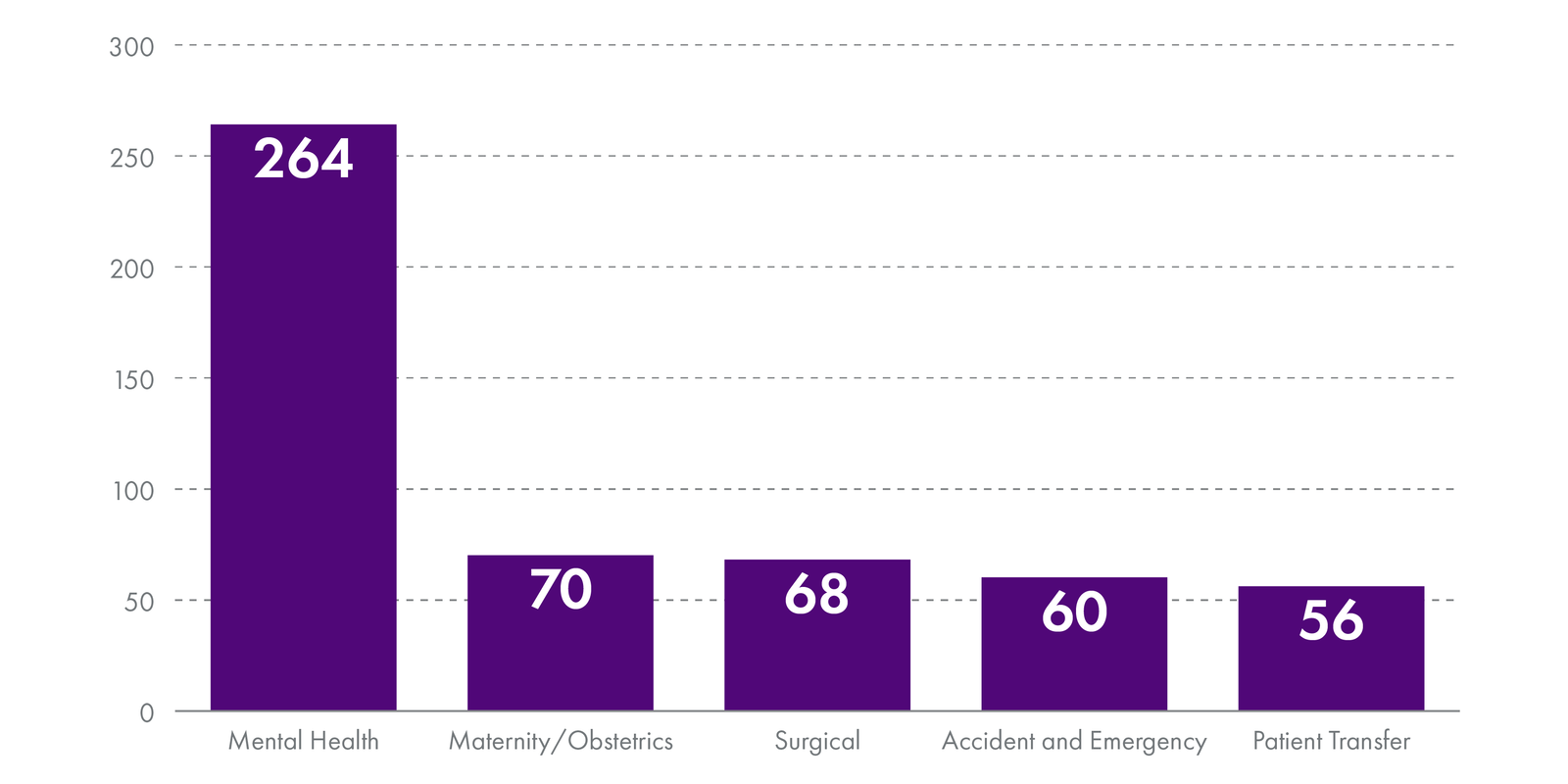

On average, the NHS in Scotland reports around 50 'category I' significant adverse event reviews every month. These are the most serious adverse events to occur in healthcare and the data shows the most common types were unexpected deaths and suicides. The areas where these were most likely to occur were in mental health, maternity/obstetrics, surgical, accident and emergency and during patient transfer.

In 2020-21 there were 278 clinical compensation payments by the NHS in Scotland, totalling £60.3 million in value.

Clinical governance in Scotland

There are already several structures and systems for ensuring good clinical governance in the NHS.

For medicines and medical devices, the main body responsible for safety is the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory products Authority (MHRA). The MHRA monitors the quality of products and responds when there are safety concerns. It does this through inspections and monitoring schemes such as the 'yellow card scheme' for medicinal side-effects, and the adverse incident reporting system for medical devices.

Responsibility for monitoring and improving the safety of patient care is shared amongst several organisations. These include NHS boards, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman, the Mental Welfare Commission and professional regulators such as the General Medical Council.

The Bill's provisions

The Bill is proposing the creation of a Patient Safety Commissioner (PSC) who would be nominated by, and accountable to, the Scottish Parliament. Parliamentary Commissioners are seen as being more independent of Government and there are seven already in place in Scotland.

The Bill proposes that the PSC would have two key functions:

To advocate for systemic improvement in the safety of healthcare.

To promote the importance of the views of patients and other members of the public in relation to the safety of health care.

Unlike the recommendation of the Cumberlege review, the PSC would have a broad remit for patient safety in general, rather than being focused on medicines and medical devices. The PSC would not consider individual cases, but instead it would monitor systemic issues. The PSC would serve a single term for a maximum of eight years.

The PSC would be required to establish an advisory group, 50% of which would be drawn from patients and their representatives. It is expected the remaining members would be drawn from people with relevant expertise.

The PSC would undertake monitoring by gathering information and investigating where it chooses to do so. It would have powers to require healthcare providers to supply information and -within a formal investigation - it would have the power to access any relevant information.

The Bill would also create a new criminal offence of breach of confidentiality which would apply to the PSC, its staff and advisory group. This would apply in instances where patient information was deliberately or negligently shared.

Once an investigation is concluded, the PSC would produce a report and lay a copy before Parliament. Recommendations would not be binding but recipients would be expected to respond within a timescale specified by the PSC.

The Financial Memorandum to the Bill proposes one full-time Commissioner, supported by three policy staff and one administrator. The estimated annual costs in the first year are £644,055.

Summary of written evidence

Responses to the Committee's call for evidence showed general support overall for the Bill. Those in support welcomed the introduction of an independent person for championing the patient voice. Those opposed to the Bill tended to think it was a waste of money and that there were better ways of improving patient safety e.g. by improving staffing and pay.

Some of the main issues raised about the Bill included:

the breadth of the PSC's patient safety remit and the potential scale of the task

the complexity of the existing governance lansdscape and the potential for the PSC to duplicate other bodies and not have a clear role

the proposal that the PSC will not take on individual cases and the potential confusion this may cause with the public

whether the PSC should also cover social care and the proposed National Care Service.

Introduction

The Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 6 October 2022 by the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care, Humza Yousaf MSP.1

The purpose of the Bill is to introduce a new Parliamentary Commissioner responsible for patient safety in Scotland.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee was designated the lead committee and will lead scrutiny on the Bill.

This briefing:

examines the background to the Bill,

explores patient safety globally and in Scotland,

details what the Bill proposes to do, and

provides a summary of the written evidence received by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee.

The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review

The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety (IMMDS) review was announced by the former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, the Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, in February 2018. It was established to look at three areas of concern:

Primodos - this was a hormonal pregnancy test drug, administered to women since the 1950s and believed to be associated with miscarriages and birth defects.

Sodium valproate in pregnancy - although an effective treatment for epilepsy, since it was licensed in the 1970s, it was known to carry a risk of birth defects if taken by women of childbearing age.

Transvaginal mesh - concerns about the use of surgical mesh in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence emerged in the 2000s when women began to report severe complications.

Each of these products was the subject of long-standing campaigns by patient groups who had experienced harm after using them.

The aim of the review was to:

Make recommendations for improving the healthcare system's ability to respond where concerns have been raised about the safety of particular clinical interventions, be they medicines or medical devices.1

Baroness Cumberlege was appointed Chair of the review group and its report 'First do no harm' was published in July 2020.2

The Cumberlege review uncovered common themes that spanned each of the interventions, despite their disparate nature.

These themes were:

they all affected women

patients were not listened to when things went wrong

patients having to turn to each other for support

the length of time for their problems to be acknowledged by the healthcare system.

Each campaign turned to politicians and the media to take up their cause.

At a press conference to launch the report, Baroness Cumberlege said:

I and members of the review team have conducted many reviews and we all agree - we have never encountered anything like this, the intensity of suffering, the fact that it lasted decades. And the sheer scale. This is not a story of a few isolated incidents. No one knows the exact numbers of affected by mesh, Primodos and sodium valproate but it is in thousands. Tens of thousands.3

Other key findings included the lack of long-term monitoring of outcomes from healthcare and how the system is not good at picking up the early signals of adverse outcomes

The report contained nine recommendations, including:

The appointment of a Patient Safety Commissioner who would be an independent public leader with a statutory responsibility. The Commissioner would champion the value of listening to patients and promoting users' perspectives in seeking improvements to patient safety around the use of medicines and medical devices.

The UK Government responded to this recommendation by tabling amendments to the Medicines and Medical Devices Bill to introduce a new Patient Safety Commissioner.

Dr Henrietta Hughes was subsequently appointed as Patient Safety Commissioner for England and took up her role on 12 September 2022.

Her work will focus on driving improvements in the safety of medicines and medical devices.

Although the IMMDS review was commissioned by the UK Government, the Scottish Government recognised the findings were also relevant to the Scottish NHS.

During a debate in the Scottish Parliament in September 2020, the then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman MSP, confirmed that the Scottish Government would implement all of the recommendations of the Cumberlege report that fell within devolved competence, including the creation of a Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland.

The Scottish Government included the proposal for a Patient Safety Commissioner in its 2020-21 Programme for Government4 and consulted on the proposal for a Commissioner focused initially on medicines and medical devices.5

Patient safety

Unsafe care is believed to be within the top 10 leading causes of death in the world, resulting in over three million deaths globally each year. This is more than deaths from lung cancer, diabetes or road traffic accidents. It is also estimated to have a disease burden similar to that of HIV/AIDS.12

In developed countries, the direct cost of unsafe care is estimated to be around 13% of healthcare spending.2 If this holds true for Scotland, that would equate to approximately £1.9 billion of spending.4

The leading causes of harm caused by unsafe care worldwide are5:

Medication errors

Healthcare associated infections

Unsafe surgical procedures

Unsafe injection practices

Diagnostic errors

Unsafe transfusion practices

Radiation errors

Sepsis

Venous thromboebolism

In 2019, the World Health Organisation declared patient safety a global public health priority.

Research has estimated that 10.8% of UK patients experience adverse events, with 47% of these being preventable.6

There are a number of datasets which can give an indication of the safety of patient care in Scotland. Some of the key datasets are outlined below.

However, it should be noted that this is unlikely to present a comprehensive view of all occasions when care could have been better. It should also be viewed in the context of the millions of healthcare interactions that take place every year.

Significant adverse events

Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) collects data on the number of significant adverse event reviews (SAERs) commissioned by NHS boards for 'category I' SAER events. These events are the most serious adverse incidents.

Category I – events that may have contributed to or resulted in permanent harm, for example unexpected death, intervention required to sustain life, severe financial loss (greater or equal to £1m), ongoing national adverse publicity (likely to be graded as major or extreme impact on NHSScotland risk assessment matrix).

Category II - events that may have contributed to or resulted in temporary harm, for example initial or prolonged treatment, intervention or monitoring required, temporary loss of service, significant financial loss, adverse local publicity (likely to be graded as minor or moderate impact on NHSScotland risk assessment matrix).

Category III – events that had the potential to cause harm but no harm occurred, for example near miss events (by either chance or intervention) or low impact events where an error occurred, but no harm resulted (likely to be graded as minor or negligible on NHSScotland risk matrix).1

In January 2022, HIS published the first national data on category I reviews.2

This showed that between January 2020 and October 2021, on average, NHS boards notified HIS of approximately 50 category I SAERs per month.

The most common types of adverse event were:

These events most often occurred in the following specialities:

Please note that there is no national data on category II and III adverse events.

Clinical Negligence and Other Risks Indemnity Scheme

Each NHS Board pays in to the Clinical Negligence and Other Risks Indemnity Scheme (CNORIS). This scheme indemnifies members against compensation claims.

In 2020-21, there were 278 clinical compensation payments totalling £60.3m in value.

The year of payment does not usually indicate the year in which the incident happened. However, the Central Legal Office for the NHS writes that claims have settled at around 250-310 per year.

Not all of these claims will relate to clinical care but contributions are based on around 91% for clinical claims and 9% non-clinical.1

Complaints

The most recent statistics show that in 2021/22, there were 35,172 complaints to the NHS. This was up 41% from the previous year.1 Not all of these will relate to patient safety issues.

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman Cases

If a patient has been through the NHS complaints system and is still unhappy with the outcome, they can refer their case to the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO). Around a third of the complaints and enquiries received by the SPSO relate to health and social care.

Of the complaints and enquiries received in relation to health, there are a variety of reasons underpinning them. Not all of them relate to patient safety but the following table details the number that fall within each broad category:

| Subject | Complaint | Enquiry | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission/discharge/transfer procedures | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| Adult social work services (NHS Highland only) | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Appointments/Admissions (delay/cancellation/waiting lists) | 87 | 0 | 87 |

| Clinical Treatment/diagnosis | 786 | 1 | 787 |

| Communication/staff attitude/dignity/confidentiality | 136 | 0 | 136 |

| Complaints handling | 23 | 0 | 23 |

| Failure to send ambulance/delay in sending ambulance | 15 | 0 | 15 |

| Hygiene/cleanliness/infection control | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Lists (inc difficulty registering and removal from lists) | 21 | 0 | 21 |

| Nurses/nursing care | 16 | 0 | 16 |

| Other | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Out of jurisdiction | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Policy/administration | 51 | 1 | 52 |

| Record keeping | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| Standard of care | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Subject unknown | 35 | 2 | 37 |

| Total | 1,238 | 4 | 1,242 |

The SPSO statistics indicate that 60% of health investigations are either partially or fully upheld.2

Current systems for monitoring and ensuring patient safety

A Patient Safety Commissioner would become part of the clinical governance systems and structures for the NHS.

Clinical governance has been defined as:

A framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish.1

Clinical governance is the process by which the quality of healthcare is monitored and assured.

The existing clinical governance systems and structures in Scotland are extensive and run through every part of the NHS. The following sections detail some of the main organisations and the mechanisms involved in ensuring patient safety and driving improvements in care quality.

Medicines and medical devices

The system for monitoring the safety of medicines and medical devices is largely separate from the systems for monitoring the safety and quality of patient care. The regulation of both medicines and medical devices is also reserved to the UK Parliament.

The key safety body in this field is the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

The MHRA covers all medicines and medical devices used in the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses. It is responsible for monitoring the quality and efficiency of products and responding quickly when safety concerns are raised.

It also aims to achieve compliance through the provision of advice and guidance to manufacturers and maintains standards of quality and safety through an inspection programme.

The MHRA also has the power to withdraw a product from the market and prosecute the manufacturer or distributor.

Other key mechanisms for monitoring safety and quality are;

the 'yellow card scheme' for reporting potential side-effects of prescription and over-the-counter medications

the adverse incident reporting system for medical devices - in Scotland this is taken forward by the Incident Reporting and Investigation Centre (IRIC) at National Services Scotland (NSS).

Patient care

The responsibility for the safety of patient care runs throughout the NHS. The following details the key bodies and mechanisms used within them for ensuring patient safety.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland

Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) is NHS Scotland's main quality improvement body . The key roles of HIS include:

setting standards for care

inspecting and auditing services

advising on managing adverse events

operating the Scottish Patient Safety Programme

the regulation of independent hospitals and clinics.

HIS does not describe itself as a 'regulator' and - unlike its role with the independent healthcare sector - it does not deal with individual complaints and cases.

On occasion, HIS will undertake reviews or investigations of particular services where there are safety concerns. For example, it has recently established a review of neonatal deaths in Scotland. This was requested by the Scottish Government following a spike in numbers.

HIS also hosts 'Community Engagement' (formerly known as the Scottish Health Council (SHC)). The establishment of the SHC dates back to 2004, when local health councils were abolished and replaced with one national council. The role of the SHC was to promote good practice in public involvement and provide patients with the opportunity to express their views.

NHS boards

NHS health boards are responsible for delivering safe, effective, person-centred care at a local level. They employ a number of mechanisms to ensure patient safety, including:

Clinical Governance Committees - each NHS board has a Clinical Governance Committee. These committees are responsible for oversight of the clinical governance within the board and assuring management that arrangements are working. They do this by monitoring and reporting on any issues that may arise. Committees should also have mechanisms for engaging with patients and staff.

NHS complaints system - NHS boards operate an internal complaints system. The information from complaints is used by boards to improve services and follows a model complaints handling procedure established by the SPSO.1

Monitoring key data and incidents - there are a number of datasets which are monitored and used to aid learning and quality improvement. Most notably this includes the recording of adverse events and incidents reported under the duty of candour.

Whistleblowing policies and whistleblowing champions - whistleblowing refers to when employees bring information on alleged wrongdoing to the attention of an employer or an external body such as a regulator. All NHS boards should have a whistleblowing policy and every board now has a 'Whistleblowing Champion'.

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman

Patients who have been through the NHS complaints procedures, but are unhappy with the outcome, can refer their case to the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO).

The SPSO also fulfils the role of the Independent National Whistleblowing Officer (INWO).

Mental Welfare Commission

The Mental Welfare Commission (MWC) is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment)(Scotland) Act 2003 and the welfare parts of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. It is independent of Government and the NHS.

The MWC also visits patients, can undertake investigations of care and services, issue reports and recommendations, as well as providing advice and good practice to patients and professionals.

Professional regulation

Most of the healthcare professions are required to be registered with a regulatory body in order to practise. These include the General Medical Council (GMC) for doctors and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) for nurses and midwives.

These bodies determine the necessary standards for education, training, skills and behaviour. They can also undertake an investigation into the practise or conduct of a registrant and determine their fitness to practise.

Regulators can remove people from the register if there are problems with their conduct or competence and it is a criminal offence to practise without being on the relevant register for that profession.

This regulation is intended to protect the public and ensure high quality care.

What is a commissioner?

There are currently seven commissioners or commissions which are nominated by the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body and appointed by the King:

Commissioner for Ethical Standards in Public Life

Scottish Biometrics Commissioner

Scottish Commissioner for Children and Young People

Scottish Human Rights Commission

Scottish Information Commissioner

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman

Standards Commission for Scotland

Commissioners are considered more independent of Government because they are appointed by and report to Parliament. As a result they can be seen to add a more robust layer of governance and scrutiny.

At the moment, most systems of clinical governance operate within NHS structures and report up the way to Scottish Ministers. The perceived lack of independence in the existing set-up has previously faced criticism. For example, the OECD has stated that the mixed roles of Healthcare Improvement Scotland as both a scrutiny and improvement body, ran the risk of Scotland's NHS 'marking its own homework'.1

The Bill's provisions

The Bill would establish the office of 'Patient Safety Commissioner for Scotland'. The purpose of the new Commissioner is described in the Policy Memorandum1 (PM) as someone who will:

promote and improve patient safety by amplifying the patient voice within the patient safety system

develop a system-wide view of the healthcare system in Scotland and use it to identify wider safety issues

promote better coordination across the patient safety landscape in Scotland in responding to concerns about safety issues.

The Commissioner would be a Parliamentary Commissioner, appointed by His Majesty the King on nomination by the Scottish Parliament, and accountable to the Scottish Parliament.

The Commissioner would serve a single term for a maximum of eight years.

More detail on the Bill's main provisions are set out in the following sections.

Functions

The Patient Safety Commissioner (PSC) would have two general functions:

To advocate for systemic improvement in the safety of healthcare.

To promote the importance of the views of patients and other members of the public in relation to the safety of health care.

In exercising those functions, the Commissioner may in particular:

gather information, for example patient feedback, relating to the safety of health care

keep under review, analyse and report on information obtained

make recommendations for systemic improvements in the safety of health care

promote public awareness of safety practices in relation to health care

promote co-ordination among health care providers.

Schedule 1 to the Bill also contains a general power for the PSC to do anything "necessary or expedient in order to achieve, or in connection with the exercise of the Commissioner's functions".

However, the Bill sets out that it would not be the role of the PSC to resolve past grievances by providing redress for any harms suffered, assisting individuals in seeking redress for harms suffered, or provide an opinion on what actions others should take in regards to an individual in order to address a past incident.

The PSC can, however, investigate past incidents in order to inform what actions need to be taken to provide systemic improvements in care.

What this essentially means is that the PSC would not get involved in individual cases, but would instead focus on safety issues at the macro level in order to drive improvements in patient safety across the board.

Principles and communication

The Bill would require the PSC to develop a statement of principles that will inform the way in which it carries out its functions. This statement would be made publicly available and include a principle that the PSC will work cooperatively with others where appropriate, while having regard to the importance of the PSC's independence.

The Bill would require the PSC to have regard to 'inclusive communication'. The Bill defines this as ensuring individuals who have communication difficulties can receive information and express themselves in ways that best meets their individual needs.

Strategic planning

The PSC would be required to develop a strategic plan that lasts no longer than four years and is publicly available.

Before making the plan, the PSC must consult on a draft with the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body (SPCB) and the PSC advisory group (see Advisory group below).

The plan would need to set out:

the strategy for involving patients and the public in the PSC's work

the PSC's objectives

proposals for achieving the objectives

the timetable for achieving the objectives

the estimated cost of doing so.

The strategy would also have to say how it would raise awareness of the PSC's role and how the public can communicate with the PSC.

The strategic plan would be laid before the Scottish Parliament.

Advisory group

The Bill would require the PSC to establish an advisory group in order to provide advice and information.

Members of the advisory group would be a matter for the PSC, but their appointment must be approved by the SPCB and at least half of the group must be made up of patients or patient representatives.

The policy memorandum to the Bill explains that remaining members are expected to be drawn from those with particular expertise, for example, clinical, legal and ethical experts.

The SPCB would decide the maximum number of group members and would also need to approve the remuneration and allowances, if any, that the PSC opts to pay members.

Investigations

The Bill gives the PSC the power to undertake formal investigations into healthcare safety issues.

A formal investigation would begin as soon as the terms of reference become publicly available.

The terms of reference must:

describe the issue to be investigated

identify (by name or description) anyone who the PSC expects to address a recommendation to in the final report

state whether the PSC will require access to the information of individuals in the course of the investigation, the reasons why the access is needed and if it will need to be provided in an anonymised way or not.

The PSC will be required to consult with the advisory group (and any others it considers appropriate) on the draft terms of reference.

Once launched, the PSC would be required - as soon as possible - to bring the investigation to the attention of anyone who may be required to provide information, or who may have a recommendation directed at them in the report of the investigation.

Information gathering

The PSC would have the power to require healthcare providers to supply any information it holds that the PSC felt relevant to their work.

This general power would not include information about an individual, or information that a person would be entitled not to provide in court proceedings (e.g. Information that may prove incriminating). Instead this information would be used for 'horizon scanning' and identifying potential systemic patient safety issues.

However, in relation to formal investigations, the PSC would have the power to access any information of relevance, including identifiable or anonymised patient information. This would need to be justified in the investigation's terms of reference, be proportionate to the issue being investigated and appropriately handled in accordance with data protection legislation.

Failure to provide the required information (without a reasonable excuse) or actions to deliberately alter it, could result in the matter being reported to the Court of Session. The Court could then make an enforcement order or treat the matter as contempt of court.

As an added protection, the Bill would create a criminal offence of breach of confidentiality around information shared with the PSC.

The offence would apply to the Commissioner, their staff (including external consultants) and members of the advisory group and relate to any instances where confidential information is deliberately or negligently shared.

If found guilty, this could result in a fine up to the statutory maximum (currently £10,000) if tried by a sheriff, or an unlimited fine if tried by a jury.

This offence would not apply to the sharing of information with a person's consent, or in instances where it was necessary for the PSC to carry out their functions. It would also not apply to disclosures for court proceedings or the investigation of a crime, or for helping HIS, the SPSO or the English PSC carry out their functions.

Investigation report

Once a formal investigation is concluded, the Bill would require the PSC to produce a report and lay a copy before Parliament.

The report would set out its findings, the reasons behind them and any recommendations. The PSC would be required to give a copy of the report to anyone that a recommendation is addressed to.

Where a report contains a recommendation which is aimed at a person or organisation, they must respond to the recommendation, so long as the PSC has given them a copy of the report and has specified a timescale for response.

That person would then have to produce a written response within the time period, setting out what they have done, or propose to do, in order to address the recommendation(s) of the PSC.

No person or organisation would be compelled by the Commissioner to accept or implement a recommendation. However, their response would need to set out the reasons for not doing so. The PSC would be allowed to publish the response (either in full or in part) or to publicise any failure to respond at all to a recommendation.

Defamation

The Bill would apply 'absolute privilege' to any statement made to the PSC and any statement in an investigation report. Any other statement by the PSC would have 'qualified privilege'.

Absolute privilege would confer complete protection against accusations of defamation. Qualified privilege would provide protection where it can be shown no malice was intended.

Other provisions

Section 22 of the Bill would give Ministers a general regulation-making power. Section 23 would allow Ministers to make any regulations for any purpose, including modifying any enactment. This would include the Bill (Act) if passed.

This is called a Henry VIII power and refers to provisions which permit Ministers to amend primary legislation using subordinate legislation.

They are sometimes seen as providing a lower level of scrutiny in that subordinate legislation is not subject to the same lengthy procedure as Bills. However, they can prove useful in instances where legislation may need to be changed quickly.

Section 22 would limit this power being used in relation to ancillary provisions required for giving full effect to the Bill's provisions.

Financial Memorandum

The estimates within the Financial Memorandum (FM) are largely predicated on there being:1

one full-time Commissioner post

four full-time support staff.

The following tables show the estimated set-up costs and the first year costs for the Commissioner, support staff, accommodation and typical office requirements:

| Set up costs | £ |

|---|---|

| Recruitment | 8,000 |

| Accommodation: fit-out and legal fees | 79,200 |

| IT, mobile and web set-up | 59,034 |

| Marketing/payroll and HR set-up | 4,000 |

| Total | 150,234 |

| Annual Running Costs (2025-26) | £ |

|---|---|

| Commissioner's remuneration | 126,119 |

| Staff salaries | 216,628 |

| Accommodation | 184,288 |

| IT maintenance | 6,600 |

| Website maintenance | 18,000 |

| Mobile devices | 840 |

| Payroll/HR services | 4,000 |

| Travel & subsistence | 6,840 |

| Advisory group expenses | 38,000 |

| Other administrative costs | 13,750 |

| Professional fees | 29,000 |

| Total | 644,065 |

As the PSC will be accountable to the Scottish Parliament, the costs will fall on the Scottish Parliament's budget, with the exception of the set-up costs and the first year running costs.

The FM assumes the post will be remunerated in line with existing Commissioners. This results in an indicative salary of £86,769 per annum, although the level of remuneration would ultimately be decided by the SPCB.

Similarly, the FM estimates three policy staff remunerated at £40,242 per annum and one administrative member of staff remunerated at £31,668 per annum. These salaries are based on the existing SPCB salary scales plus a 3% inflationary uplift.

The FM states that the estimates are based on comparator bodies and advice from SPCB officials.

For comparative purposes, table 5 shows the most recent level of remuneration, staffing and the provisional budget (2023-24) for all of the Scottish Parliamentary Commissioners and Commissions. This would indicate that the PSC would be one of the smaller Parliamentary Commissioners, sitting somewhere in between the Scottish Biometrics Commissioner and the Scottish Human Rights Commission.

The English PSC is being remunerated at a rate of £105,000 per annum but there is no public information on staffing or budget.2

| Name | Annual salary band (2021-22) | Full-time equivalent staff (2021-22) | Total provisional budget 2023-24 (subject to parliamentary approval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish Public Services Ombudsman3 | £90-95,000 | 77.51 plus the SPSO | £6,155,000 |

| Scottish Information Commissioner4 | £75-79,000 | 23.9 including the Commissioner | £2,232,000 |

| Ethical Standards Commissioner5 | £75-79,000 | 9.6 including the Commissioner | £1,606,000 |

| Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland6 | £70-75,000 (*2020/21 data) | 14.4 including the Commissioner (*2020/21 data) | £1,536,000 |

| Scottish Human Rights Commission7 | £70-75,000 (Chair) | 12.8 + 4 Commission members | £1,341,000 |

| Scottish Biometrics Commissioner8 | £65-70,000 | 4 including the Commissioner | £444,000 |

| Standards Commission for Scotland9 | £10-15 (Chair) and £70-75,000 (Executive Director) | 3.1 plus 5 Commission Members | £338,000 |

The FM also assumes there will be some costs associated with the proposed advisory group. The Bill requires 50% of the group to be comprised of patients and their representatives. The remaining 50% will be expected to consist of necessary experts such as lawyers, clinicians and academics.

The FM anticipates costs of £26,000-38,000 associated with reimbursing the time and expenses of patient representatives who are not in employment. This is based on a payment of £300 per day and £50 travel expenses, although this will depend on the number of unemployed group members and the amount of virtual meetings.

There are no similar expected costs for other advisory group members.

Summary of written evidence

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee issued a written call for evidence on the Bill which ran from the 26 October to 14 December 2022.

There were 54 responses to the call for views, with 40 from organisations and 14 from individual members of the public.

General opinion on the Bill

Respondents were not explicitly asked if they supported the Bill or not, but of those that expressed a clear view, 35 were supportive and 10 were opposed. The remainder either provided qualified support or their opinion was not clear.

Those who expressed support for the Bill generally expressed the following views:

They welcomed having a focus for the patient voice. These submissions believed that there are a number of reasons why the patient voice is currently not heard. These included the complexity of the system and the power imbalance that exists between patients and health professionals.

They welcomed the broader remit beyond medicines and medical devices to include all aspects of patient safety.

They welcomed the statutory basis to the role and its independence from Government - believing this will ensure public trust.

Those opposed to the Bill generally expressed the opinion that it is a waste of money. These submissions tended to feel that patient safety would be better improved by spending the money on safe staffing, increasing pay, improving the provision of social care and reducing NHS managers.

All of the submissions opposed to the Bill came from individual members of the public, while the supportive responses were largely from organisations working in the health and social care field.

Those with a more mixed response to the Bill tended to question whether the role as set out in the Bill would be able to significantly improve the underlying problems which cause patient safety issues in the NHS.

There were some common themes expressed across submissions both in support and opposed to the Bill. Some of these are detailed in the following sections.

Roles and responsibilities

Remit

Some submissions welcomed the breadth of the PSC remit beyond the Cumberlege review recommendation it should only cover medicines and medical devices. They thought this would be less confusing for patients.

However, some also expressed concerns about the potential scale of the task given the all-encompassing nature of 'patient safety' and questioned whether the PSC would be adequately equipped and resourced to do it justice.

Cluttered scrutiny landscape and duplication

One of the most common themes to emerge related to the complexity of the existing scrutiny landscape and the potential for a new PSC to overlap with current governance structures and systems.

Some submissions felt it was not entirely clear how the PSC would fit in the current system and how they would add value. Many mentioned the potential for duplication.

This breadth of remit is matched by a concerning lack of clarity about the relationship between, and overlap with, existing organisations. This is not in patients’ interests.

There is already a complex regulatory, scrutiny and oversight landscape for the NHS in Scotland; my concern is that creation of another oversight/ scrutiny body where their function and remit is not clearly articulated within the context of the wider landscape, will add confusion for patients (and those delivering services), and unnecessary administrative burden for an already overstretched NHS. Crucially, in my view this will not enable access to justice. (Scottish Public Services Ombudsman)1

Individual complaints

There were some differing views on the Bill preventing the PSC taking on individual cases. Most welcomed the focus on systemic issues but others felt it could be an artificial distinction.

Nevertheless, a common theme on both sides was the need to make it clear to the public that this would be the case, otherwise it was felt it would lead to confusion and patients being let down.

If I saw ‘Patient Safety Commissioner’ I would think that’s someone I could go to, but if they only deal with certain domains I would feel utterly betrayed. (Member of The Alliance)

Social care

A number of submissions felt that the PSC should also cover social care and questioned how the Bill would take account of the National Care Service and the intersection between health and social care.

Some felt that many of the systemic safety issues in the NHS also occur in the care sector. Some also suggested the Scottish Government should await the outcome of the Dame Sue Bruce review on the regulation of social care.

Powers

A minority of submissions raised specific issues with the powers that would be available to the PSC. Of those that did, the most discernible theme was a feeling that the PSC would not have any powers to improve the things that really matter for patient safety e.g. funding, staff numbers and pay.

These comments were generally made by those opposed to the Bill and were expressed alongside a fear that the PSC would become another way to berate and punish staff.

Using the powers with constraint was seen as essential for nurturing a culture of openness and this was expressed by both those in support and opposition to the Bill.

Some other submissions also questioned whether the PSC powers would add anything to what is already there and suggested the NHS should try to improve on that first.

There were some specific suggestions for additions, amendments or clarification of the PSC's powers, including:

Giving the PSC powers to compel more than just healthcare providers to provide evidence, for example, private companies. This was mentioned in light of the fact that the recommendation for the role stemmed from issues with medicines and medical devices.

The PSC should have powers equal to that of a Health and Safety Executive inspector under s20(2) and 25 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.

Allow the PSC to make disclosures to professional regulators where there are fitness to practise concerns.

Other submissions were generally content with the proposed powers of the PSC.

Appointment process and funding

The intention for the PSC to be appointed and accountable to Parliament was welcomed by many of the submissions. This was seen as providing greater independence from Government and necessary to garner public trust.

However, some submissions felt there could be potential resource concerns given the broad scope of the role and what might be considered as relatively modest resources. It was suggested there was a mismatch between the ambitions for the office and the budget set out in the Financial Memorandum.

While I have expressed concerns above about the Commissioner's investigatory role, and the confusion for users that the legislation encourages, the resources given to the office mean the Commissioner would, in my view, be unable in practice to dedicate the staff resource required to undertake investigatory work on anything other than an exceptional basis.

It is also important to note that the work undertaken prior to an investigation when deciding what to investigate and the scope of that investigation, can be significant and the current proposed resources may even struggle with those early stages. (Scottish Public Services Ombudsman)1

On a similar note, some respondents believed that whoever became the PSC would need to have significant attributes such as empathy, medical knowledge, legal expertise, analytical skills and ethical understanding, as well as the ability to work with people and organisations. Some felt that these skills are unlikely to be found in one person therefore the PSC will need a good team to support them.

Suggested changes or alternatives

Respondents made a significant number of suggestions on changes or alternatives to the Bill. Some of these are listed below:

Establish a discrete role for the PSC, perhaps around ensuring the voice of the patient is heard.

Redraft the investigatory functions of the PSC to have a clearer focus.

Clarify how the PSC will interact with the National Care Service.

Add a definition of 'patient safety'.

The PSC should have regard to established principles in other legislation.

Include clear objectives or an evaluation clause to assess the effectiveness of the PSC.

Include aesthetic procedures and other types of private healthcare within the remit of the PSC.

Clarify the membership of the advisory group.