Flats: management, maintenance and repairs

When a person owns a flat they have an interest in what happens to the building as a whole. However, working together with other flat owners to manage and maintain the building can be difficult in practice. This briefing looks at some of the associated law and policy, as well as offering practical advice which might help support people in this situation.

Executive Summary

A range of repair and maintenance problems

Flats are an important part of Scotland's housing stock. In buildings which contain flats lots of different repairs and maintenance problems can arise. The condition of some of these buildings is relatively poor, particularly the older ones.

While there are plenty of incentives for flat owners to work together to maintain or improve their building, there are challenges in practice.

Uncertainty amongst flat owners

Sometimes flat owners are unclear as to who is responsible for dealing with maintenance and repair problems affecting the building, believing that some responsibility might lie with, for example, the local council.

In fact, a flat owner has the primary responsibility for repairs and maintenance to his or her flat. In addition, flat owners usually have some collective responsibility for repairs and maintenance to other important parts of the building.

The situation does not change significantly if an owner rents his or her flat out. Flat owners still retain the main responsibilities even if they rent out their properties.

See Rights and responsibilities of flat owners.

The role of property managers or factors

In some parts of the country, such as urban areas on the west coast of Scotland, it has been very common for there to be a property manager or factor for the building.More widely across Scotland, many modern developments and increasing numbers of traditional blocks, especially in urban areas, will have a property manager or factor.

In return for payment, this person or organisation typically undertakes tasks, including arranging repairs or maintenance to buildings and their grounds.

The property factoring sector is now regulated under the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011. Under this legislation, there is a Code of Conduct, setting out minimum standards of service which registered property factors have to meet.

In certain circumstances, a flat owner can complain to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) if the factor is not complying with the Code of Conduct, or certain other parts of the 2011 Act.

However, difficulties can still arise between flat owners and factors. Changing factors if owners are not happy with their current service is an area where the law is particularly complex.

See Property managers or factors.

Getting owners to work together effectively

Sometimes owners can struggle to work together effectively in relation to necessary repairs and maintenance.

The Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 is an important piece of legislation, containing the Tenement Management Scheme (TMS). The TMS applies where the official ownership documents of the building (known as the title deeds) do not make alternative arrangements.A key policy innovation of the TMS is that it allows binding decisions by simple majority (51%) on a range of issues.

However, some housing experts question whether this legislation, and other related legislation, have delivered improvements to the condition of buildings in practice.1

Resolving disputes

Local sheriff courts have responsibility for resolving disputes relating to the TMS.

These courts are also a key forum for resolving disputes about whether a title condition has been disobeyed by a flat owner. A title condition is a form of legal obligation contained in the title deeds.

Public bodies do not have general responsibility for enforcement action in relation to breaches of the rules in the TMS or a title condition. Usually flat owners must raise a court action themselves.

See The Tenement Management Scheme, Working together with other flat owners and Resolving Disputes.

The role the local council plays

The local council has a variety of statutory powers to require that owners carry out certain repairs. However, the council also usually has a good deal of discretion as to whether it uses the powers or not, unless a building is classified as dangerous. When public finances are tight, the powers are typically used as a last resort.

See A council's powers relating to repairs.

Difficulties paying for repairs

In Scotland, there is not a culture amongst flat owners of anticipating future work and saving together for it.2 This means owners can struggle to pay when something unexpected happens or when parts of the building with a limited lifespan wear out.

Councils can offer assistance to private owners to carry out repairs. However, nowadays the assistance is typically not financial support.

See Paying for repairs.

What this briefing covers

This briefing begins with an explanation of how flats fit into the landscape of Scottish housing.

It also provides a brief overview of current policy issues affecting the sector. The overview includes a description of various policy initiatives that may bring about reform in future.

The remainder of the briefing looks at a wide range of topics related to flats on which SPICe regularly receives enquiries from constituency offices. For example, in the order they appear in the briefing:

how a flat owner can take decisions with other flat owners on repairs and maintenance, and how the costs of these will be divided up between owners. The briefing looks at both the role the building's title deeds might play in this, as well as the statutory Tenement Management Scheme

the property factor or manager's role in relation to a building, including what to do if a flat owner is not happy with the service provided by their existing factor or manager

how to work together effectively with other flat owners in practice, including how to track down absent flat owners and how to resolve disputes when things go wrong

Title deeds or title documents?

Note that, throughout this briefing, we refer to the official registered documents associated with ownership of a property as the title deeds, reflecting the fact that this is a term still in regular use in practice.

However, it is more accurate these days to refer to such official records as the title, or the title documents, to the property. This shift in legal terminology is associated with key differences in the format of the two existing property registers in Scotland. The Land Register now contains most of Scotland's land and buildings, in which context the newer terminology is more accurate.

Flats as a type of housing

Flats are an important part of Scottish life, accounting for around 902,000 homes, 37% of Scotland's housing stock.1

The most common housing type in urban areas is the flat, accounting for around 40% of urban housing. Only 11% of rural dwellings are flats.2

Flats account for 66% of the homes provided by housing associations. Flats are also a particularly important part of the private rented sector, as 67% of the homes leased by private landlords are flats.3

The Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, an important piece of legislation on shared repairs, defines tenement broadly, to include all buildings containing flats.i

The wide statutory definition is important because flats are found in a wide range of buildings, not just the traditional pre-war sandstone or granite building:

There are more modern blocks of flats, including high rise blocks.

Flats can also be found in four in a block properties, typically built as social housing in the 20th Century. Each flat has a separate entrance, taking the form of a stair for an upper flat.

Developers tend to market brand new buildings as apartment blocks. These can have extensive common areas and facilities, such as underground parking and landscaped garden grounds, which can be expensive to maintain.

Some buildings contain flats as a result of a change of use, such as large houses which have been subdivided or former commercial or public sector buildings.

Some buildings also currently have a mixture of flats and commercial units, such as shops or offices.

All these types of buildings containing flats fall within the scope of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, and in the scope of this briefing.

The Under One Roof website has a good section on buildings containing flats from different eras. It looks at the different types of construction materials used, and methods of construction. It includes a description of some key issues that can arise in respect of each type of building.

The policy background to this briefing

Going into the new parliamentary session, there are various policy issues affecting tenements.

The state of Scotland's flats and why this matters

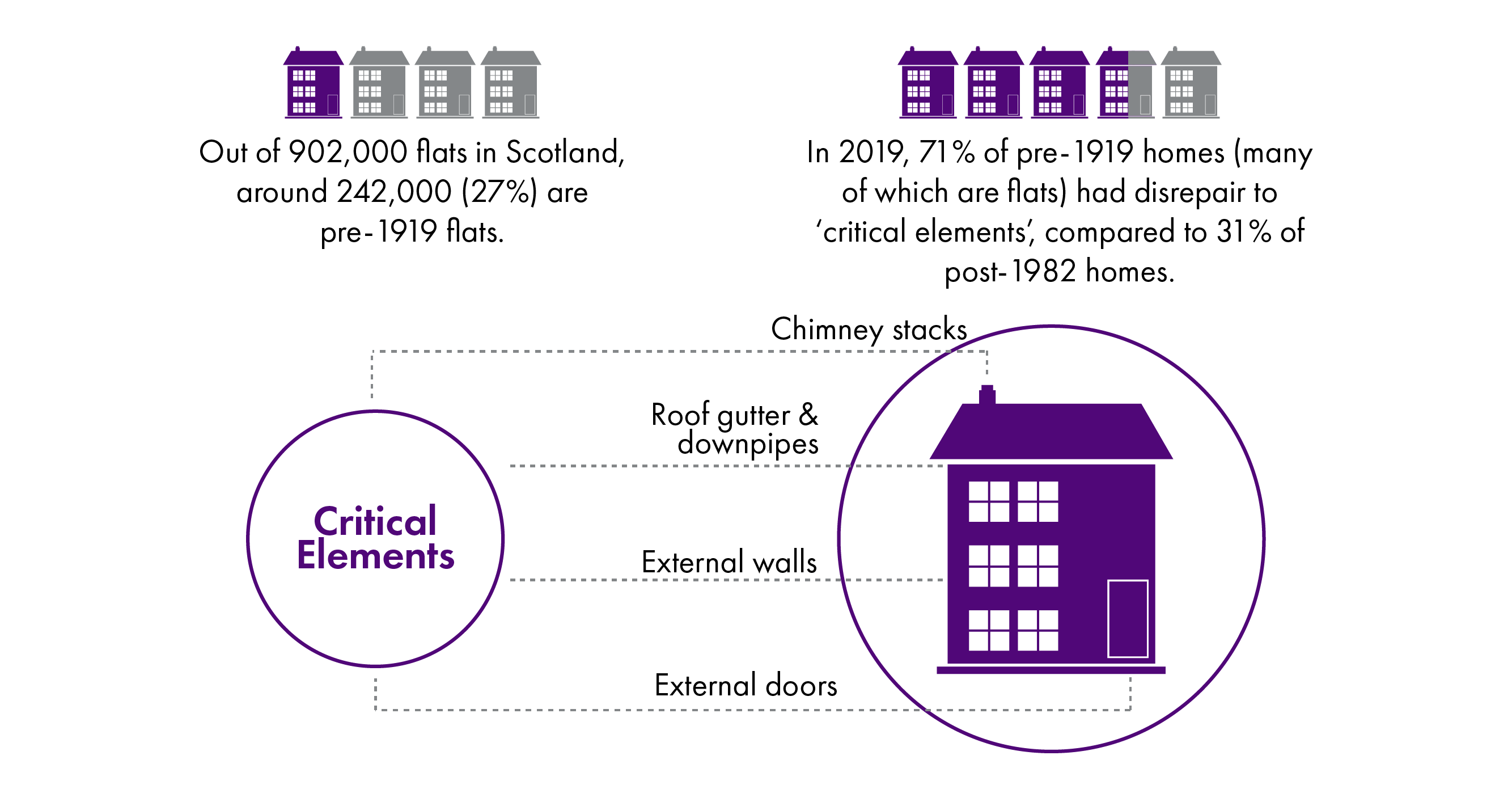

The condition of some buildings containing flats, particularly the older ones, is relatively poor. Older homes tend to have higher levels of disrepair to ‘critical elements’, that is those that are central to weather-tightness and structural stability.1

If poor condition is not addressed, buildings will fall into more serious disrepair, becoming more expensive to repair and difficult for owners to sell. Ultimately, they may turn into a ‘ticking-time bomb’ becoming dangerous and, in the worst examples, demolition might be the only option.2

The fire at Grenfell Tower raises a variety of complex legal and policy issues.3 Many of these are outside the scope of this briefing and some of them relate to differences between English and Scottish property law. However, at the most basic level, Grenfell showed that issues with a building (containing flats) can sometimes have extremely serious consequences, affecting multiple owners.

The Scottish Government’s ambitious climate change strategy4 also has the potential to shine a spotlight in future on the condition of flats as a type of housing.

This climate change strategy will require significant changes to Scotland’s buildings to make them more energy efficient and use low carbon heating systems. It will require an increasing focus on retrofitting existing homes to meet the necessary standards.

The nature of buildings containing flats is such that these changes are likely to require owners to agree on work to common areas or sections of the building. As the Scottish Government signalled in its draft Heat in Buildings Strategy, new primary legislation may be needed to support this.52

The challenges of working together

There are then clear incentives for flat owners to work together to repair, maintain and, if necessary improve, their buildings. However, in one block, each flat owner might have very different priorities and resources. Some might be keen to maintain, or improve the building, others might be unwilling or unable to pay for this.

Sometimes it may even be difficult to identify who owns a particular flat, for example, if it is rented out by an investor landlord.

Significantly, there is not really a culture in Scotland of long-term saving by owners for future repairs,1 even though this is critical to the long-term health of buildings.

In some parts of the Scotland, particularly in urban areas on the west coast, such as Glasgow, it has been very common to have a property factor, also known as a property manager.2

More widely across Scotland, many modern developments and increasing numbers of traditional blocks, especially in urban areas, will also have a property manager or factor. For modern developments, contracts associated with any communal areas of ground are particularly common.

In return for payment, the factor or manager typically undertakes tasks including arranging repairs or maintenance. However, factors or managers can be asked to organise repairs when required, rather than a proactive programme of ongoing maintenance. There may also still be issues with the availability of factoring companies who can undertake work for owners in rural areas.

A further complication is that, in one building, it is possible to have a mixture of flats which are social housing, flats which are private rentals (including holiday accommodation) and flats lived in by their owners. In this situation, property owners have a diverse range of interests in the building, as well as very varied financial positions.

At present, there is no uniform statutory standard imposed on these different types of owners, in terms of the required condition of their accommodation. Social housing providers must make sure their homes meet quality and energy efficiency standards set by the Scottish Government. However, such providers can struggle to work with other owners to agree repairs or improvements to the building related to those standards.

There were various reforms in the early part of the 21st Century designed to improve the condition of Scotland's housing, and encourage owners to work together on repairs and maintenance. These are explored in more detail later in the briefing. The relevant legislation includes the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, which introduced the Tenement Management Scheme. This aims to provide a legal mechanism for effective decision-making in tenements (where the buildings' title deeds do not provide this). Another key piece of legislation was the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, introducing a range of new powers for councils.

However, Professor Douglas Robertson, a leading housing academic, has argued that:

...despite this plethora of useful reforms …the actual impact on the ground has proved fairly negligible. If anything, matters now appear to have got worse.

Robertson, D. (2019, November). Why Flats Fall Down: Navigating Shared Responsibilities for their Repair and Maintenance, p 23 . Retrieved from https://thinkhouse.org.uk/site/assets/files/1345/befs0120.pdf

Reform - but not for a while

In 2019, a report by the Scottish Parliament Working Group on Tenement Maintenance was published. It recommended a parliamentary Bill to be introduced by 2025. This would require:1

owners’ associations, to try and involve all owners in decision-making

building reserve funds, to enable long-term saving by flat owners for repairs

building surveys every five years, for regular identification of repairs issues.

In late 2019, the Scottish Government responded to the Group’s report, agreeing, with caveats, that action was needed. In particular, the Government questioned whether the Group's ambition of legislation by 2025 on the above topics was achievable.2

In March 2021, the Scottish Government’s Housing to 2040 strategy was published (the Strategy).3 One solid commitment, likely to be helpful in the context of tenements, is a common housing quality standard for all types of homes, backed by an enforcement framework. For this, the Strategy envisages a new law in 2024-25, implemented in phases from 2025 to 2030.

However, where the Strategy refers to the report of the parliamentary working group, or topics covered by it, its approach lacks detail in places. It is not exactly clear what the commitments in the Strategy mean for the Group’s goal of (wider) legislation by 2025 and fundamental change to tenement law. In addition, the Scottish Government's work plan for 2021 on the condition of tenements, also published in March 2021, does not mention the possibility of such legislation.

Given the scale of the issues facing tenements, it is easy to see how the Government might end up facing pressure to achieve faster reform. One thing SPICe can predict though is that, for just now, the problems will remain very real ‘on the ground.’ The weight in the constituency postbag is unlikely to get lighter any time soon.

The remainder of this briefing explains the current law and practice, with the aim of offering support for MSPs' constituency case work in this area.

How a tenement building is owned

Routinely, certain important parts of a tenement building in which all (or several) flats have a mutual interest are the common property of those flat owners.

For example, as explained in more detail later, the communal passage and stair for a building (known as the close in Scotland) is normally common property.

Common property is a legal term which refers to the main way of co-owning property in Scotland. All owners of common property have a right to access and use all parts of that property and their ownership is not restricted to a particular physical section of the common property. For example, it's not the case that one flat owner owns (and has access to) one end of the common property and the owner of another flat owns (and has access to) the other end. All owners of common property can access all parts of that property.

For tenements, common property can exist by virtue of specific rules in the building's title deeds or fallback statutory rules.

Some parts of the tenement building and its grounds will also be in individual ownership, the main alternative to common property. For example, a single ground floor flat might also own the garden. Again, a particular outcome for an individual building will be because of what the title deeds say, or the fallback statutory rules.

In Scotland, we used to have a type of ownership where flat owners owned property subject to certain rights held by a legal entity called a feudal superior. Although traces of their former existence still appear on some title deeds, feudal superiors were abolished in 2004.i Ownership of a flat, or the building it is in, is no longer subject to another 'layer' of ownership. However, a flat owner may still find that their neighbours may still have certain rights over their flat, based on rules of property law which remain in the post-feudal world. This topic is explored in more detail in several later sections of this briefing.

Rights and responsibilities of flat owners

In this section of the briefing we explain what the law says about the rights and responsibilities of flat owners.

Sometimes flat owners are unclear as to who is responsible for dealing with repairs and maintenance issues affecting their building, believing that some responsibility might lie with, for example, the local council. However, a key point is that flat owners have primary responsibility in this area. This principle applies both in terms of:

an individual flat

the other sections or areas of the tenement building, and its grounds, in which flat owners have a mutual interest.

The situation does not change significantly if a flat is rented out. Tenants usually only have responsibility:

under statute, as 'occupiers', for the cleanliness of the common areasi

under a typical tenancy agreement, for minor repairs to the flat's interior decoration and for damage caused by the tenant's negligence, or the negligence of any person the tenant has invited into the property.

Details of flat owners' rights and responsibilities can be found in:

the title deeds relating to the building, considered in the next section of the briefing

the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, discussed in detail in various later sections of the briefing.

Why the title deeds are important

An important starting point for any flat owner is to look at their title deeds.

The title deeds are the legal documents associated with a building which, in the context of a tenement, explain:

who owns the different parts of the tenement building

the legal rights and obligations which apply to a flat owner as a result of the title deeds.

A flat owner might also need to find out information from the title deeds of a neighbouring flat, if, for example:

They don't know who owns a particular flat, for example, because it is rented out.

There is a suggestion from a neighbour that their title deeds differ on important topics, such as how the cost of repairs should be divided up.

Getting the title deeds

The title deeds relating to a property can be obtained from:

The mortgage lender or solicitor

A flat owner's mortgage lender or the solicitor who did the conveyancing should be able to provide a flat owner with a copy of their title deeds.

The mortgage lender or solicitor may propose to charge a fee for this service. If so, the flat owner should consider how those fees compare to those charged by Registers of Scotland before proceeding.

Registers of Scotland

Information about a flat will also appear in one of the two (publicly searchable) property registers. These are either the Land Register for Scotland or the original Register of Sasines, which is in the process of being phased out.

The Registers of Scotland, the public body which is responsible for managing both registers, provides some information about ownership of some flats without charge (e.g. sale price and date of sale). This is through its online public portal, Scotland's Land Information Service, or ScotLIS for short. For a fee, copy title deeds relating to properties registered in the Land Register can also be ordered through this portal. At the time of writing, this fee is £3 plus VAT.

In addition, staff at Registers of Scotland can, for a fee, manually search its registers with the aim of finding out who owns a particular flat and provide copies of title deeds. Private search companies also offer services in this area.

What determines how a tenement building is owned

The title deeds often stipulate that parts of the tenement building or its grounds are common property.

There are two key points on this area. First, the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 provides fallback rules on the ownership of the tenement building, to the extent the title deeds are silent, or say conflicting things between the different flats.i

Some of these statutory rules probably match the expectations of the public, for example, the communal passage and stair of the building (known as a close in Scotland) is common property under these default rules.ii Others are perhaps more surprising. For example, the fallback rule for the roof is that it is owned by the owners of the top floor flat(s) immediately below. (Where there is more than one top floor flat, owners own the section above their flat.)iii

The default rules also mean that ownership of an individual flat includes the external walls of the building which surround it, meaning that, unless the title deeds say otherwise, a 'patchwork' of ownership of these walls is created across the exterior of the building.iv

The second key point on this topic is that ownership does not, of itself, determine who is responsible for maintenance and repairs to these parts:

Title conditions in the flats' title deeds, considered in the next section of these briefing, can play an important role.

The statutory Tenement Management Scheme,v also discussed later in the briefing, provides fallback rules on management and maintenance, in the event the title deeds are silent or defective in some way.

Title conditions: a type of legal obligation found in title deeds

Title conditions are a group of legal obligations, and associated rights, found in the title deeds of land or buildings, including in those title deeds which apply to a tenement.

Title conditions are imposed on (or burden) one property or a group of properties, and benefit a neighbouring property or group of properties.

If a rule in a title condition is not being followed, a benefited property owner or owners has the right to enforce a title condition against a burdened property owner or owners. This topic is explored in more detail later, in relation to one specific type of title conditionknown as a real burden.

Note that in tenement blocks, you often find a common scheme of title conditions. This is a group of title conditions applying to the whole block, so that all flats are both benefited and burdened properties. Such title conditions are mutually enforceable by the flat owners against each other.

Because of complex legal rules, including those set out in the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 and the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003, a title condition which appears in the title deeds might not be valid or still in force.1 A flat owner would have to take legal advice on this in an individual case.

Assuming, however, a particular title condition is valid and in force, it survives changes of ownership of the benefited and burdened properties.

In law, owners of affected properties are regarded as having accepted the title conditions when they bought the property. In practice, there seem to be varying levels of awareness among flat owners of the title conditions affecting their property.2

Solicitors do have a professional duty to explain what obligations are contained in title conditions prior to any purchase. However, it may be too easy for purchasers to overlook the information when focused on other aspects of the house buying process.3

Types of title condition - real burdens and servitudes

There are a couple of types of title condition of which to be aware:

real burdens (or burdens) which can require an owner to do something (for example, pay for a share of a cost) or restrict owners from doing something (such as using a flat to run a business).

servitudes which oblige an owner to let another person use or access their property for a specific purpose.

A real burden (or burden) is the main type of title condition associated with flats. Some common examples include burdens stipulating:

who is responsible for maintaining and repairing common property

how decisions should be made by owners about repairs and maintenance

how repair and maintenance costs should be split between owners

whether there is a property manager or factor or an owners' association (or both) and what this person or organisation can do.

A burden requiring someone to do something (e.g. pay a cost) is binding on the flat owner only. However, burdens preventing someone from doing something (e.g. running a business from a flat) are binding on flat owners and also certain occupiers of a flat, including tenants.i

Enforcing a real burden

Sometimes a real burden exists but the terms of that burden are not being followed. This situation is referred to by lawyers as being in breach of the burden.

A key issue is who can take action to make the person in breach comply with the burden, known as enforcing a burden. Another important issue is what steps can be taken by way of enforcement.

An important point is that there is no public body with general powers to proactively enforce burdens when they are breached, in court or by other means.

Instead, individuals or organisations with enforcement rights can include:

Owners of neighbouring flats, who often have rights to enforce burdens against each other. Precisely which flat owners in an individual case may be set out in the title deeds expressly, or implied by complex statutory rules.i Note a public body such as a council can be an owner of a flat in an individual case.

Tenants of flats (where those flat owners have enforcement rights) can also enforce burdens against neighbours subject to the burden.ii This is relatively unusual in practice.

When we talk about enforcing a burden, the remedy of last resort requires a person or organisation to bring a civil court action in the local sheriff court.

The Tenement Management Scheme

The Tenement Management Scheme (TMS), contained in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, is a fallback scheme for managing and maintaining buildings containing flats.

The TMS can be used when the flat owners' title deeds have gaps, defects or contradictions in their coverage of particular topics. For example, the title deeds may not say how decisions should be taken. They might also, for example, allocate responsibility for shares of costs to flat owners which do not add up to 100%.

Among other things, the TMS:

defines key terms associated with the scheme, including what is known as scheme property. These are the parts everyone is required to maintain, regardless of how they are owned

describes how flat owners make decisions about scheme property - known as scheme decisions

says what should happen when there are emergency repairs.

More about these parts of the TMS are explained in this section of the briefing. However, on the topic of how the TMS might apply to an individual building, legal advice is recommended.

Note that most of the rights and obligations in the TMS apply to owners not tenants. This can lead to a situation where, to take decisions and spend money jointly, there is a need to trace an owner who is currently renting a flat out. On this, see the later section of the briefing, called Tracking down owners.

Some aspects of the TMS are contained in the main body of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004. However, the detailed rules are contained in Schedule 1 of the Act. References in this briefing to the TMS rules are to the rules in Schedule 1.

Some key terms

This section of the briefing discusses the key terms of tenements, maintenance and scheme property, as these are crucial to understanding the TMS.

Tenement

As noted earlier, under section 26 of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 (the 2004 Act) a tenement is defined broadly. It is a building including two or more related flats that are divided from each other horizontally. It usually includes the ground on which the building stands and any land relating to the building.

The title deeds (including any burdens) can be used to help determine whether flats are related for the purpose of this definition. In complex cases, legal advice is recommended.

Maintenance

Many of the legal rights and obligations of flat owners under the TMS only apply when maintenance is being considered or carried out. The TMS defines maintenance as including:i

repairs and replacement, the installation of insulation, cleaning, painting and other routine works, gardening, the day to day running of a tenement and the reinstatement of a part, but not most, of the tenement building

It says maintenance does not include:i

demolition, alteration or improvement unless reasonably incidental to the maintenance

SPICe cannot provide advice on whether an activity falls within the scope of the TMS in an individual case, where this is uncertain. A constituent may wish to take legal advice.

Scheme property

The TMS applies to scheme property. Scheme property can be divided into three main categories:i

any part of the tenement which the title deeds say is the common property of two or more flat owners

any other parts of the tenement that burdens say two or more owners must maintain

various other structurally important parts of the building, however they are owned.

It is this third category which takes the scope of the TMS beyond any scheme for owners set out in the typical set of title deeds. The third category includes:ii

the ground which the block is built on

its foundations

its external walls

its roof (including any rafter or other structure supporting the roof)

if it is separated from another building by a gable wall, the part of the gable wall that is part of the tenement building

any wall, beam or column that is load bearing.

Some parts of the building are specifically excluded from the third category, as follows:iii

any extension which forms part of only one flat

any door, window, skylight, vent or other opening which is used by only one flat

any chimney stack or flue.

SPICe cannot give advice on whether something falls within the scope of scheme property in an individual case, where this is uncertain. It is recommended a constituent takes legal advice.

Taking scheme decisions

One of the key policy aims of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 was to enable flat owners to work together effectively to manage and maintain their tenements.

What is a scheme decision?

The TMS allows flat owners (not tenants) to take decisions together on a variety of topics related to scheme property. These are known as scheme decisions.

Where the title deeds do not provide an alternative voting arrangement, scheme decisions are made by a simple majority (i.e. 51%) of the votes allocated to flat owners. i

A key feature of the scheme is that there is one vote per flat.ii This means, for example, that if a couple live in their co-owned flat, it is still the case that only one vote may be cast.

A properly made scheme decision applies to flat owners even if they did not vote in favour of it. When a flat is later sold, a valid scheme decision also applies to the incoming owner. However, in both instances there are certain rights to appeal the decision.iii

It is possible for a person or organisation to own more than one flat in a block. They get one vote for each flat owned.

This issue often comes up in so-called mixed tenure blocks, where some flats are privately owned and others are owned by a council or housing association. If the council or housing association owns the majority of flats in the block, then the 'one vote per flat' rule gives them considerable influence in scheme decisions as the scheme works on the basis of majority voting.

What can flat owners decide on?

Scheme decisions can be taken to:i

carry out maintenance to scheme property, including instructing a particular person or firm to do the work

require the owners to pay a deposit towards the work

arrange for an inspection of scheme property for maintenance purposes

appoint or dismiss a property manager or factor in some circumstances (see Changing Property Factors)

delegate powers to that manager or factor, including the power to carry out or organise maintenance

arrange a common insurance policy for the block (see Common Insurance)

install (or replace) a door-entry system for the block which can be controlled from each flat

decide that an owner does not have to pay any or all of his or her share of a cost

authorise any maintenance of scheme property which has already been carried out

change or cancel any previous decision.

Several of these powers refer to maintenance. Work might not qualify as maintenance under the TMS because it is an improvement to the building which is not reasonably incidental to the maintenance.

For improvements, where the title deeds do not say anything to the contrary, the unanimous agreement of all flat owners is required.

Following the correct procedures

The TMS has procedures for scheme decisions. Compared to some statutory schemes, there is not a high level of formality associated with these. However, it is still important to follow procedures carefully.

In particular, the TMS makes specific provision to cover the situation where an individual owner was not notified in advance that there was going to be a scheme decision to incur expenditure. If, on finding out about that decision afterwards, the owner immediately objects to that decision, they not liable for the associated costs.i

The main points associated with the relevant procedures are set out below.ii

All owners entitled to vote must get at least 48 hours' notice in writing of any meeting associated with a decision.

If a meeting is not to be held, all owners with a vote on the issue must be asked what they think, unless there is a good reason not to do this.

Owners must keep a written note of the votes cast.

Getting owners' views in practice

Going door to door or sending an email or text message might be good approaches in practice to obtain owners' views. The City of Edinburgh Council has recently introduced a Shared Repairs app, with one aim that this will help with owners' decision making.

Sharing the costs of repairs and maintenance

Rule 4 of the TMS sets out the default position for how costs associated with a scheme decision should be shared between flat owners.

Equal sharing for some types of costs

For some types of costs there is a simple rule under the TMS that the costs are always equally shared between all the flats.i

Such costs include installing (or replacing) a communal door entry system; management or factoring fees; fees associated with calculating floor areas of flats and other costs relating to management (not further defined).ii

A more complex set of rules for other categories of costs

For other categories of costs (mainly) associated with maintenance under the TMS, there are more complicated rules. They will often result in equal sharing in practice.i The main rules are set out in the box below.

TMS rules for certain categories of costs

Rule 1

For common property, costs are shared between the flats in proportion to the relevant shares of ownership of the common property.ii

An exception to rule 1 is where the common property is the roof over the close or the common passage and stairs. Then the rule is equal sharing, unless the flats are of significantly different sizes.iii

Rule 2

For other types of scheme property, the general rule is that the costs are shared equally between the flats. However, it can be shared according to floor area, where the floor area of the largest flat is more than one-and-a-half times that of the smallest flat.iv

Rule 3

For parts of the building which are not scheme property, the owners of the part pay equal shares of the costs.

There are also special rules for costs associated with insurance policies.v See Common Insurance.

Challenging scheme decisions

As explained earlier, the starting point of the TMS is that a properly made scheme decision applies to owners even if they voted against it. However, there are some additional points here worth noting.

Appeal rights for flat owners

Section 5 of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 says an owner who voted against a scheme decision can challenge it in the local sheriff court.

A new owner who wasn't an owner when the scheme decision was made also has this right.

The owner must apply to the court within:

28 days of the meeting where the decision was taken; or

where there was no such meeting, within 28 days of being notified of the decision.

The sheriff may cancel the decision (in whole or in part) if he or she thinks it is not in the best interests of the owners taken as a group or is unfairly prejudicial to one or more owners.

Where the decision relates to maintenance (or improvements or alterations incidental to maintenance) the sheriff can take into account various issues. These include:

the age of the property

its condition

the cost of the works

the reasonableness of that cost in making his or her decision.

Right of veto for owners who would pay 75% of the costs

A special category of flat owners can also cancel a scheme decision by giving notice to the other owners.i These are owners (or indeed a single owner) who:

did not vote in favour; and

would be liable for not less than 75% of the costs of maintenance.

In other words this procedure can be used by one owner for whom the financial effect of the decision would be particularly significant. They could block maintenance for the whole building.

The flat owners in question have to cancel not later than 21 days:

after any meeting associated with the decision; or

after the date on which an owner was notified.

Where there is a group of owners wanting to exercise this veto, it is the date the last owner was notified that counts.

Who can enforce scheme decisions

As mentioned earlier, there is no public body with general powers to enforce scheme decisions under the TMS.

Scheme decisions can be enforced by:

the flat owners against each other.i Note a flat owner might be a public body such as a council.

a person authorised in writing by a flat owner to do so.ii An owner's tenant, or the property factor for the building, are examples of people who might be authorised in an individual case.

A council where it has paid a missing share of the maintenance or repairs costs for a particular tenement (when an owner cannot or will not pay). See Help from the council - missing shares. ii

As with burdens, to enforce a scheme decision, those with enforcement rights may have to raise a court action in the sheriff court. See Resolving Disputes.

Emergency work

Owners have powers under the TMS to carry out emergency work.i

Emergency work means work which requires to be carried out to scheme property to:

prevent damage to any part of the tenement; or

in the interests of health or safety.ii

Emergency work can be instructed without a scheme decision, which in practice means that one owner can get the work done without having to get the others to consent. Responsibility for the cost of the work is still divided up in the usual way though. In other words, in accordance with the general rules set out in rule 4 of the TMS.

SPICe cannot assist with how the definition of emergency work applies to individual cases. A constituent may wish to take legal advice. In the event of a dispute which cannot be resolved, it may be a court which will ultimately decide the issue.

Consumer Focus Scotland commented in 2009 on the scope of the emergency repairs rule as follows:

Few repairs are likely to be this urgent ... in any dispute over such work, you and your fellow owners must be able to justify what you have done, or you may appear to have acted without following proper procedures and may find it difficult to recover costs. If you cannot prove it was an emergency, you may find yourselves paying for the cost of the work.

Consumer Focus Scotland. (2009). Common Repairs, Common Sense - a short guide to the management of tenements in Scotland. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/resource/0041/00417200.pdf

Support and shelter - including the duty to maintain

For repairs and maintenance of tenements, the TMS is the best known part of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004. However, it is important not to overlook the additional statutory duties on flat owners in sections 8-10 of the 2004 Act.

Section 8 imposes a duty on flat owners to maintain the parts of the tenement that provide support and shelter. For example, a roof provides shelter, a structural wall provides support.

Section 9 forbids material interference by an owner or occupier with the support and shelter provided to any part of the tenement building.

These duties are useful because they are not just concerned with common parts of the building but the condition of, and the activities associated with, the individual flats themselves. They reflect the fact that the poor maintenance in parts of individual flats can damage the whole building.

Any single flat owner directly affected by a breach of either duty can enforce their rights in the local sheriff court. See Resolving Disputes. This can be helpful if one owner is struggling to get the majority of owners required under the TMS for making scheme decisions.

A court will apply a test of reasonableness in determining what the content of the section 8 duty is. The court can look at the age and condition of the building and the likely cost of the work.

Common insurance

Section 18 of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 makes it compulsory for owners to insure their flats.

What the law says in more detail

The statutory duty to insure a flat is for the reinstatement value, that is to say the total cost of rebuilding the flat from scratch. It may not be the same as the current market value of the flat.

Owners must insure against prescribed risks set out in secondary legislation.

The prescribed risks include, among others:i

fire

storm or flood

vandalism

subsidence

escape of water from water tanks, pipes, apparatus and domestic appliances

accidental damage to underground services.

The statutory duty to insure also applies to a flat's pertinents. This slightly old-fashioned legal term refers to:

the parts of the building which the law says belongs to an individual flat in a particular case

any share of common property a flat owner has in another (co-owned) part of the building.

Pertinents can be created by the tenement's title deeds, or, to the extent these are silent on the topic, the fallback rules relating to ownership in the 2004 Act.ii

Examples of pertinents in the fallback rules include:

the right a flat owner has over the close, the Scottish term for the common passage and stair (which these rules say is owned as common property)

a chimney stack serving one flat (owned by that flat) or a right of common property in a chimney stack which serves several flats.iii

The title deeds sometimes require the owners to take out one common policy of insurance for the whole building. However, the 2004 Act does not require this.

Where the title deeds are silent on insurance, owners might choose:

one common policy of insurance for the entire building

for each flat owner to individually insure their flat and its pertinents

to have a combination of individual and common policies. For example, each flat owner takes out a policy for their own flats, but the flat owners agree the other parts of the building will have a common policy of insurance.

Taking decisions about insurance and paying for it

The TMS has various fallback rules on organising insurance and paying for it.

The flat owners can take a scheme decision to get a common policy of insurance. The associated premiums should be paid in the proportions they agree when this decision is reached.i Where the common policy is arranged because of a burden in the title deeds, the TMS says the premiums should be paid equally.ii

Property managers or factors

Owners in a block of flats might use the services of a property manager or factor to help manage and maintain the building, or be interested in moving to this system. Here we cover some issues associated with this topic.

First of all, a note on terminology:

property manager is the term used by the Property Managers Association Scotland, and found in some legislation (for example, the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004).

property factor (abbreviated to factor) is a more common alternative term, which also appears in legislation (the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011).

The remainder of this section of the briefing uses the term property factor.

In practice, a property factor can carry out many jobs, such as:

arranging for maintenance, repairs and inspections

running a joint maintenance account and collecting payments from flat owners

setting up common insurance for the building or regular contracts for cleaning, lift maintenance or gardening

organising meetings for owners to make decisions about the building.

How property factors are appointed

A property factor might be appointed because:

A requirement in the title deeds

A burden requiring a property factor for a particular tenement might name a particular person or organisation who must be appointed, or who has the power to decide who the property factor should be.

Some title deeds (on the face of the deeds at least) give the developer, council or housing association a permanent right to be a factor or to appoint a factor. This type of burden is known as a manager burden. These burdens can be controversial in practice because some owners do not want to be bound in this way.

In practice though, the right associated with a manager burden is not permanent, in spite of what the title deeds say. It is limited by section 63 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003. This (complex) provision sets out various maximum time limits for manager burdens. Some more detail is set out in the section of the briefing called Changing Property Factors. Legal advice is recommended in individual cases.

Owners take the initiative

Owners might also decide to appoint a factor on their own initiative.

The Under One Roof website, run by a charity and sponsored by a variety of public and private sector sources, contains practical advice on topics including whether a property factor is needed, and what to look for in a property factor.

The Tenement Management Scheme says flat owners can appoint a factor by a scheme decision.i This rule applies as long as there are no decision-making powers for owners in the title deeds and no manager burden in force.

A scheme decision can also delegate powers to the firm or person in question.ii

What service contracts do

There is also often a separate service contract between the flat owners and the factor. As the name suggests, this sets out the key services to be provided.

When there is nothing about factors in the title deeds, this is the main source of legal rights and obligations. However, a service contract can also add to what the title deeds say on more detailed aspects of the services provided.

Regulation of property factors

Factors are regulated under the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011 and related secondary legislation. The details of this regime are explored in the remainder of this section of the briefing.

Depending on their activities, property factors may have to meet the requirements of statutory bodies such as the Scottish Housing Regulator. Some factors are also social landlords and this body regulates such landlords.

Factors may also have to conform to rules and codes of practice of professional or industry bodies, such as the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) or the Property Managers Association Scotland (PMAS). For RICS, it may be possible to take complaints to this body in individual cases. On the other hand, PMAS does not have a role in resolving complaints from clients of their member firms.

The Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011: an overview

The 2011 Act defines property factor broadly. It includes private businesses, local authorities and housing associations.i

The system of regulation under the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011 ('the 2011 Act') has three main parts:

A factor must register on the Scottish Property Factor Register, maintained by the Scottish Government, if they want to operate in Scotland. Operating as a factor without being registered, and without reasonable excuse, is a criminal offence.ii

There is a Code of Conduct, prepared by the Scottish Government, setting out minimum standards of service which registered property factors have to meet.iii

There is also a process for resolving disputes between the flat owner and the factor. A flat owner or flat owners can complain to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) ('the First-tier Tribunal') if the factor is not complying with the Code of Conduct or certain other parts of the 2011 Act.

The Scottish Government has published a guide to registration. Although written from the applicant's perspective, it does contain a useful summary of the legal requirements property factors must comply with after registration.

Registration and de-registration of property factors

As noted earlier, registration on the Scottish Property Factor Register is compulsory for property factors operating in Scotland. Registration is only granted where factors are assessed by the Scottish Government as fit and proper to operate.i

If registration is approved, it applies for a period of three yearsii with the consequence that re-registration is needed every three years.

The Scottish Property Factor Register lets a member of the public search online to find out:

whether a person or body is registered (if the member of the public is already dealing with that person or body)

in other circumstances, who the property factor may be for a certain property address or area of land

the contact details of a certain property factor

the latest number of properties a property factor manages.

Property factors are responsible for making sure that the information on the register is correct and is in line with any relevant legislation.

On the first bullet point above, note that most people or bodies offering factoring services should be registered. However, it is still advisable for a flat owner to check this, if they are involved in a dispute with a body or person providing those services.

Being unregistered affects factors' ability to recover costs from flat owners associated with work to a tenement, or to charge flat owners for services.iii Unregistered property factors can also be reported to the police or to the Scottish Government.

Factors can be de-registered in various circumstances, including where they have failed to comply with the Code of Conduct or where the Scottish Government considers the factor to no longer be a fit and proper person.

De-registration is the ultimate sanction, which, in practice, would likely be used as a last resort, in the event of serious and unresolved failures. The powers of the First-tier Tribunal provide a wider range of sanctions. For example, the Tribunal can issue a Property Factor Enforcement Order (PFEO), iv requiring the property factor to do something or to make a payment to the homeowner as is considered reasonable.

The legislation links the two aspects of the system of regulation though, by saying that the First-tier Tribunal can provide information to Ministers which might result in de-registration.v

The Code of Conduct

As noted earlier, property factors have to comply with the Code of Conduct (the Code).

The first version of the Code was introduced in October 2012. Following a Scottish Government consultation on a draft of a possible new version of the Code in 2017-18,1 relevant secondary legislation was passed by the Scottish Parliament in early 2021.i This brought the revised version of the Code into force on 16 August 2021.

An online article by a private firm of solicitors provides a useful summary of how the revised version of the Code otherwise compares to the original version.

The Code consists of two main parts:

the written statement of services, which property factors are required, under the Code, to give to flat owners

general service standards imposed on the factor, which cover six individual themes.

There is some overlap between the two parts of the Code in terms of their content. The written statement of services is considered in more detail in the next section of this briefing, the general service standards in the section which follows that.

An innovation of the revised version of the Code is that there are also new Overarching Standards of Practice that property factors should apply in carrying out their work. Again, there is some overlap with other parts of the Code here, in terms of the content of these standards.

Written statement of services

The written statement of services is a key part of the system. It is meant to provide a simple and clear overview of the standards which the property factor will meet when providing services.

This statement should cover topics including the core services provided, with target times for taking action. It should explain, among other things, the factor's arrangements for:

charging owners

recovering outstanding debts

handling complaints.

It should also explain the factor's financial or other interests in the building, for example if the factor is also a letting agent or landlord for any flat.

The written statement must give clear information on how flat owners can change or end the arrangement with the particular factor.

General service standards

The Code of Conduct also requires property factors to meet other general service standards. As noted earlier, these cover six themes:

On debts owed by owners, charges imposed for late payments must not be “unreasonable or excessive,” with the further requirement that these charges must be clearly identified on any relevant bill or statement issued to the owner.1 When dealing with customers in default or in arrears difficulties, a property factor should treat its customers,

fairly, with forbearance and due consideration to provide reasonable time for them to comply.

Scottish Government. (2021, July 14). Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011: Code of Conduct for Property Factors, para 4.5. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/property-factors-scotland-act-2011-code-conduct-property-factors-2/pages/6/

When arranging repairs and maintenance, the factor must be able to show why contractors were appointed. The factor must also consider a range of repair options and have arrangements in place to ensure this. For any work, the costs should be balanced with the quality of the work and the end result, and the long-term benefits. Where appropriate, factors should recommend professional advice.3

When organising repairs and maintenance,4 or arranging insurance on behalf of owners,5 the factor must also disclose any financial relationships with contractors and insurance providers (or any intermediaries of an insurance provider). This would include a commission paid by an organisation to the factor for recommending a particular contractor, provider or intermediary.

Property factor duties

The 2011 Act also requires the factor to fulfil property factor duties. These are:

duties in relation to the management of the common parts of land owned by the homeowner, or

duties relating to the management of land.i

Some burdens relating to factors in the title deeds may fall into this category, as well as obligations under the service contract. It may be helpful for flat owners to get legal advice in individual cases.

Applying to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber)

The First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) consists of members who are specialists in housing and land management issues. It is based in Glasgow.

The 2011 Act envisages that complaints or disputes will first be dealt with between the parties concerned. No application can be made to the First-tier Tribunal until:

the property factor has been given a reasonable opportunity to resolve the dispute or complaint

the factor has refused to resolve, or has unreasonably delayed in resolving, the flat owner's concern.i

Flat owners who have disputes with a property factor are able to apply to the Tribunal requesting it to decide whether the property factor has failed:ii

The Tribunal can look into a wide range of matters, including whether the fees are transparent and match with the written statement. However, a key point is that it cannot take a view on whether the fee charged by a property factor is, of itself, excessive or otherwise unjustified.

There is no fee for applying to the Tribunal and it is not necessary to be represented by a solicitor. However, sometimes it may be helpful to get legal advice on specific points, especially if the costs of this can be shared between flat owners.

If a complaint is upheld, the Tribunal can issue a Property Factor Enforcement Order (PFEO).iii This, in turn, requires the factor to do something to correct the situation or to make a payment to the homeowner as is considered reasonable.iv It is a criminal offence to fail to comply with a PFEO, without reasonable excuse.v

Changing property factors

The issue of whether a factor can be dismissed and a new one appointed is a very complex one. It is not dealt with by the 2011 Act. Instead you have to look at the title deeds. This is in conjunction with fallback powers in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 ('2004 Act') and the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 ('2003 Act').

The steps necessary to dismiss a factor will vary according to what the title deeds say. The following key points may be helpful:

The title deeds might give a procedure for dismissing a factor, for example two thirds of flat owners have to vote in favour of the move. In this situation, owners should follow the what the title deeds say (but see 3, 4 and 5 below)

The title deeds might not say anything about a procedure or are conflicting about the procedure owners should use. The owners can then follow the rules in the Tenement Management Scheme. These say that a property factor can be dismissed on a vote of a simple majority (51%) of flat ownersi

Regardless of what the title deeds say, section 64 of the 2003 Act stipulates that two thirds of flat owners can vote not to use an existing factor anymore and to hire a new one. Section 64 is useful if it would be particularly difficult to meet the requirements on this in the title conditions - for example, the deeds say that the owners must agree unanimously (but see 4 and 5 below).

Usually, section 64 cannot be used if a manager burden, which gives someone the right to be a factor or appoint a factor, exists. However, there is an exception to this general rule for ex-council properties bought under the 'right to buy' legislation. See also 5 below on time limits for manager burdens.

Regardless of what the title deeds say on the duration of a manager burden, various maximum time limits on manager burdens are set by section 63 of the 2003 Act.

On point 5, the main rules in section 63 say that a manager burden comes to an end on the earliest of the following dates:

the point the manager burden says the burden comes to an end

the relevant date, which is three years (for sheltered or retirement housing), thirty years (for homes bought from local authorities under the 'right to buy' legislation) or five years (for other types of housing).

the date owners of ex-council properties act together to dismiss the factor using section 64 (as described in point 4 above)

90 days after the point the person who can be a factor, or appoint a factor, under a manager burden stops owning a property in a development.

This is an incredibly complex area of law and legal advice is strongly recommended.

Working together with other flat owners

This section of the briefing moves from an entirely legal focus to some practical sources of information, which it is hoped will be helpful for when constituency offices are advising members of the public.

Communication and decision-making

One way a tenement building is more likely to be well managed is if the flat owners communicate well with each other. Day-to-day, this can be done in person, informally, by knocking on doors, by having regular meetings or by a mixture of the two approaches. Email can also be useful.

Routine contact gives people a chance to discuss issues, iron out misunderstandings and make better decisions.

The Under One Roof website has a number of practical resources which can help flat owners communicate effectively with each other, including through meetings. See, for example:

Owners' associations

Owners in a block of flats might want to consider an owners' association.As noted earlier in the briefing, the Scottish Parliament's Working Group on Tenement Maintenance recommended that this should be a mandatory requirement in future.1

What is an owners' association?

An owners' association is a group of flat owners who act together to tackle issues of shared concern. It can supplement the role of a property factor for a particular building. It can also be an alternative to having a property factor.

A committee made up of some of the association's members can run things on a day-to-day basis.

Sometimes the title deeds say that there should be an owners' association and set out requirements as to how it should be run. This is particularly likely to be the case in modern developments. Sometimes owners take the initiative to set one up.

There are a couple of good practical resources on the suggested advantages of owners' associations, as well as how to create and run such an association:

Setting up and Running an Owners' Association (published by Argyll and Bute Council but with some good general information on such associations)

the section of the Under One Roof website on owners' associations.

What form does an association take?

Owners' associations in Scotland take two main forms.

Unincorporated associations

An owners' association is most commonly set up as an unincorporated association. This means that legally the association does not have a separate identity from the individual owners. it is not recognised separately from the individual owners.

As a result, an association does not have the power to sign a contract, for example, with a builder, maintenance contractor or factor. It also does not have powers to take legal action through the civil courts in its own name, for example, for non-payment of a bill. In these examples it would need to be the individual owners that would do these things on behalf of the association.

Development Management Associations

For larger or more complicated developments, Part 6 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003, in conjunction with secondary legislation,i may be relevant.

Under this legislation, developers (or owners acting together) can opt into a comprehensive management scheme (the Development Management Scheme) via the title deeds. Some new developments have this scheme, although it is not common in practice.1 It is particularly suited to developments with extensive common parts needing maintenance.

The associated Development Management Association (DMA), a key part of the scheme, is a legal entity in its own right. This, in turn, means it is more straightforward when the association wants to enter into a contract or take legal action as it can do so in its own name.

However, a DMA is more expensive to run. It also needs to be set up by a professional adviser, such as a solicitor (due to the requirement to opt in via the title deeds).

Tracking down owners

As mentioned earlier in the briefing, one issue flat owners may encounter is that they may need to contact, and work with, other owners in the block who aren't living in the flat they own. For example, if the flat is rented out, or lying empty.

If the flat is rented out

Any tenant(s) in the flat in question may be able to give details of a landlord or any letting agent. The letting agent can, in turn, can contact the landlord.

All private landlords must be registered - they are listed on central register. It is possible to search the Scottish landlord register for details of a particular landlord.

If the flat is empty

Where the flat is empty, it may be worth contacting the Empty Homes Officer in the local council. While they will not be able to give out an owner's contact details, they may be able to give useful background on the flat in question. For example, they may be able to say contact has already made with the owner and to describe previous attempts to bring the property back into use.

Shelter Scotland has a useful section of its website with some initial ideas and tips to address the challenges posed by empty homes. This includes information about its Empty Homes Advice Service.

Approaches which might be helpful in a range of circumstances

There are some other ways to track down property owners, which are worth noting.

Searching the property registers

The title deeds should give the owner's name and address at the time of sale, although this is less useful if the property last changed hands some time ago. Also note that, for recent purchases, the property registers can take some months to update.

Companies, partnerships and trusts

Owners who are companies, partnerships or trusts raise particular issues in terms of tracking down owners.

The term 'company' is probably self-explanatory, but note, that for the purposes of this particular discussion, a partnership is similar to a company. The firm has a legal identity distinct from the individual partners of the firm.

With a trust, the situation is particularly complex in terms of the people involved. The owner of property has transferred property to trustees. Trustees hold the property for specific purposes on behalf of those benefiting from the property in practice (the beneficiaries).

For all three types of entity, it can be difficult to know who to write to and what their contact address is. The information provided by the property registers is not designed for this purpose.

A company may be identified in the property registers by its registered office, rather than the actual place of business (which would be most useful when contacting a company).

Using the name of the company, a person might be able to discover its place of business from free sources on the web. A search of the Register of Companies can also provide additional information about the company. Some of its information is free, such as the names and correspondence addresses of individual directors.

As noted above, trustees can own property on behalf of a trust. This is also true for partners in relation to a partnership. However (for technical reasons it is not necessary to explain) not all the trustees or partners might be named on the property's title deeds. At the time of writing, there is no public register which provides an alternative source of information about such individuals, or indeed provides detailed information about any trust or partnership.

The Register of Persons Holding a Controlled Interest in Land, which becomes operational from 1 April 2022, aims to show who has significant influence or control over an owner of property. This will improve the information available about trustees and partners not named on the title deeds.

Private detectives

Private detectives can attempt to trace people whose whereabouts are not known. This may be appropriate in some circumstances.

Fees are charged for this service, although some may operate on a 'no find, no fee' basis. A solicitor may be helpful in identifying private detectives who operate reputable services.

Access to flats for maintenance and other purposes

Sometimes a flat owner may want to access a part of the building (wholly or partly) owned by someone else. The main reasons a flat owner (or owners) can require access are:

to carry out maintenance or other work required as a result of the Tenement Management Scheme, the Development Management Scheme or burdens in the title deeds

to carry out maintenance to a flat (or other part of the building) actually owned by the person or people requiring access (for example, if a contractor working on an upstairs flat wants to put a ladder in a garden owned by the downstairs flat)

to carry out an inspection to decide whether maintenance is necessary

to assess whether an owner is complying with the duty of support and shelter in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004

to calculate the floor space of a person's flat. This is sometimes necessary for dividing up costs associated with a scheme decision or a burden.

Servitudes or, less commonly, real burdens in title deedsi for particular buildings may create rights of access for flat owners to individually owned parts of the tenement building (for limited purposes). For example, to carry out the maintenance a flat owner is obliged to do by virtue of another burden.

In addition, section 17 of the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 (the 2004 Act) gives a statutory right of access for flat owners to parts of the tenement which are individually owned where certain conditions are satisfied. Under section 17 of the 2004 Act, access must be for the reasons set out in the bullet points above.

That flat owner needs to get reasonable notice before he or she must give access, except in cases of emergency. A flat owner can refuse to give access, or access at a particular time, if, in the circumstances, it is reasonable to do so.

Separately, section 19 of the 2004 Act includes rules associated with the installation of service pipes. Specifically, section 19(1) entitles an owner of a flat to lead pipes, cables or other equipment through any part of the tenement (apart from parts wholly within another owner’s flat).

This right exists to provide a flat with services prescribed in regulations, currently restricted to gas and heating services.ii

Resolving disputes

There are various different ways of resolving disputes, summarised in this section of the briefing. The section begins with taking court action, although this is usually used as a last resort.

Taking court action

Taking court action in the local sheriff court is a key way a flat owner can enforce his or her rights for various aspects of the law relating to flats.

Sheriff courts do not specialise in property law issues, they hear a wide range of civil and criminal cases.

A court can order a person to do various things, including pay a debt or take some other specific action, for example, carry out repairs. A court order can also require a person to stop doing something.

Potential drawbacks

There are potential drawbacks to court action. For example, unless someone fully qualifies for legal aid, there will be costs which have to be incurred, such as fees payable to the court (court fees) and to the solicitor (legal fees).

In addition, even if a court action is successful, this does not mean that debts will be immediately repaid, or work carried out. If a court order is not complied with, there are potential additional legal costs associated with that. Specific court proceedings (for example, debt recovery actions) often have to be raised with the aim of remedying any breach.

Other potential drawbacks include the possibility that relationships with their neighbours will deteriorate significantly as a result of court action. Engaging with the court process, of itself, can also cause additional stress.

The court process

The sheriff court, like other courts, operates based on specific procedures.

A new simple procedure was introduced in the sheriff courts late in 2016. It is intended to be a speedy and informal way to resolve disputes. It applies where the value of the claim, such as the debt owed by the person being sued, is £5,000 or less.

Under this procedure having a solicitor representing the person bringing or defending the action, whilst possible, is not required (or indeed encouraged). Accordingly, the costs are typically much lower than in other court procedures.

Note that legal aid to pay for the costs of a solicitor representing a litigant is not available for the simple procedure. This is because of the intention that the procedure should be able to be used without the help of a solicitor.

Simple procedure is best suited to straightforward debt recovery cases. Cases requiring a good understanding of complex legal concepts associated with legislation or title deeds can greatly benefit from a solicitor investigating and presenting the case.

In addition, a person may want to stop somebody doing something (via a court order known as an interdict). They may also want to make somebody do something other than pay money (via a court order known as a specific implement). Usually the ordinary procedure is then used.

In addition, where the value of the claim is over £5,000 the ordinary procedure applies.

A flat owner wishing to use the ordinary procedure in the sheriff court should speak to a solicitor.

Alternatives to court action

Because of the drawbacks associated with court action, flat owners can often benefit from trying to resolve their disputes outside the court process, at least in first instance.

Before resorting to the simple procedure in the sheriff court, flat owners must be able to demonstrate the steps they have taken to resolve the dispute out of court.

Negotiation with other flat owners

A first step may be to negotiate directly with the flat owner or owners who are not complying to try and resolve the problem. The (previously mentioned) section of the Under One Roof website on difficult conversations may be useful here.

Mediation

Mediation is another alternative to court that can be worth trying in some circumstances. This is a process which involves an independent third party helping two sides to come to agreement.

People in dispute can also be directed to mediation by the sheriff court as part of the simple procedure.

A local mediator, including one who specialises in community and neighbour mediation, can be found through the search facility of the Scottish Mediation Network.

Sometimes local councils can also recommend particular providers or have an in-house service.

Note that mediation has its own drawbacks. For example, the people in dispute have to be willing to take the initiative and participate voluntarily. The conclusions reached in these circumstances, unlike a court order, are also not legally binding, unless agreed otherwise.

Mediation is also not always free at the point of use. There are private mediation providers who charge fees. Mediation is not suitable for situations where there is a threat to a person's safety.

A solicitor's letter

Another alternative to court action - or, more accurately, a preliminary legal step which may mean court action is unnecessary - is a solicitor's letter.

Here a solicitor, on the instructions of a flat owner, will write to another flat owner. The solicitor will remind them of their legal obligations and the possibility of court action.

Solicitors' letters incur legal fees, unless these are fully met by legal aid. They are more likely to be a useful alternative to court action for certain types of claim, including higher value claims or complex cases where the simple procedure does not apply.

A local authority's powers in relation to the condition of housing

Local authorities have a range of duties and powers contained in different pieces of legislation to deal with issues in privately owned housing, including flats.