Energy Policy - Subject Profile

In the coming parliamentary session, a rapidly changing and increasingly complex energy landscape will lead to multiple converging issues affecting the way that energy for electricity, heat and transport is produced and used. This briefing provides an introduction to the key policy issues and recent developments in Scotland and the UK, in a global context.

Summary

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) undertakes to keep global mean surface temperature rise to “well below” 2°C and to “pursue efforts” to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C. An immediate and massive deployment of all available clean and efficient energy technologies, combined with a major push to accelerate innovation and reducing energy usage are fundamental to achieving this.

The 26th United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP 26), to be held in Glasgow in November 2021, is the largest international negotiation ever in the UK. This summit aims to bring heads of state and experts together to accelerate action towards the goals of the UNFCCC. It is one of the most important climate conferences ever, and widely considered to be the last opportunity to deliver on commitments to keep global temperature rises within safe limits.

As well as addressing climate change, other key considerations are security of supply, affordability, and developing energy policy which is acceptable to the public, economically sustainable and just.

In the UK, energy consumption has fluctuated significantly in the last 18 months with use falling to a record low due to Covid-19; however, energy use and greenhouse gas emissions are set to rebound in 2021 unless take swift action is taken.

Electricity represents only 22% of Scotland's total energy consumption, with higher requirements for both heat (51%) and transport (25%). Most societies still rely predominantly on cheap fossil fuels to function. UK and Scottish policy is aligned with global agreements - to date, policies have mostly targeted the decarbonisation of electricity, however focus is now shifting to the heat and transport sectors. UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a developing international framework.

Key pieces of primary legislation underpinning UK energy policy include the Climate Change Act 2008, and the Energy Acts of 2013 and 2016. The Climate Change Act sets a target of net zero emissions by 2050. The Energy Acts reform the electricity market to support security of supply and support low carbon generation, and create an Oil and Gas Authority to regulate fossil fuel extraction with a remit to maximise economic recovery, whilst also supporting the move to net zero.

In November 2020 the UK Government published a Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, with a focus on delivering new and advanced nuclear power; low and zero emission transport; investing in carbon capture, usage and storage; and green finance and innovation.

Whilst their role in electricity generation has reduced significantly over the last ten years, fossil fuels remain the largest part (76%) of Scotland's total energy consumption, and underpin much of the economy. First and foremost, the move to net zero emissions will require significant and wide ranging demand reduction (e.g. through reducing private transport use and insulating buildings), electrifying many energy systems, and using hydrogen energy where electricity does not provide sufficient power. Innovation to allow the continuing use of hydrocarbons in some areas (using carbon capture and storage) is also anticipated. There are significant hurdles to widespread hydrogen deployment as well as carbon capture, use and storage.

The climate crisis and Glasgow's hosting of COP26 has intensified discussions about the ongoing role of oil and gas in energy systems and the economy, with a particular focus on development of the Cambo Oil Field west of the Shetland Islands, and a just transition for the industry. The International Energy Agency has recently recommended that there should be no investment in new fossil fuel supply projects.

Energy efficiency, and high energy prices, link directly with health and well-being. In Scotland, a household is defined as in fuel poverty if it needs to spend more than 10% of its adjusted net income on fuel to maintain a satisfactory heating regime. Fuel poverty is caused by poor energy efficiency, low incomes, and high domestic fuel prices. Sustainable solutions to fuel poverty include improving the quality of housing stock and community heating schemes.

The promotion of renewable energy, the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development, and the promotion of energy efficiency are currently devolved. This allows the Scottish Government to focus attention on advancing research, development and deployment in key areas, and gives Ministers some powers in governing the overall energy mix, including nuclear and other thermal generation via consenting powers.

Overall Scottish policy is supported by key documents, as well as renewable energy generation and greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets. These targets include a 75% reduction in emissions by 2030 and net zero emissions by 2045; as well as an all energy (heat, transport and electricity) renewables target of 50% by 2030. The Scottish Government considers energy efficiency to be the cornerstone of their approach, and seeks to remove "poor energy efficiency as a driver for fuel poverty" and to reduce "greenhouse gas emissions through more energy efficient buildings and decarbonising our heat supply".

The Scottish Government's Energy Strategy sets out its vision for the energy system in Scotland to 2050. It articulates priorities for an integrated system-wide approach that considers both the use and supply of energy for heat, power and transport; it has three core themes:

A whole system view: examining where energy comes from and how it is used – for power (electricity), heat and transport

An inclusive energy transition: driven by the need to decarbonise the whole energy system, in line with net zero commitments; this must be a "just transition" to tackle inequality and poverty, and to promote a fair and inclusive jobs market

A smarter local energy model: a smarter, more coordinated approach to planning and meeting distinct local needs by linking local generation/use and developing local energy economies.

The most recent update to the Scottish Climate Change Plan assumes that by 2032, Scotland's renewable electricity capacity will more than double, reflecting increased demand from electrification of transport and heating. A new Energy Strategy is expected to be published in 2021 taking into account Scotland's net zero emissions target and setting out key actions and staging posts for the energy sector to support this.

Parliamentary scrutiny throughout Session 5 recognised the scale and complexity of balancing competing issues in the whole energy system, and the need for strategic oversight to ensure good governance, policy expertise, cross-party buy-in (as there has been for climate change) and long-term ownership of the issues. A new National Public Energy Agency is expected to be created in Session 6 to oversee the transition to a decarbonised whole energy system.

Introduction - sources and pathways

Energy can be thought of as a system, it comes from a number of different sources, and travels many different pathways 1:

Energy vs Electricity vs Power

Energy and electricity are sometimes conflated and referred to interchangeably. However, electricity is only one form of energy. For example a country may be described as having a high proportion of renewables in its energy mix, but usually it is the electricity mix that is being referred to, and the proportion of the energy mix that is renewable is much lower. Power is also often used in this area – e.g. the power sector, a power plant. The difference between the terms is set out below:

Energy: energy is defined as the capacity to do work. There are several types or forms of energy, such as kinetic, light, sound etc. The main types relevant for energy policy are electrical energy, heat energy, nuclear energy, and chemical energy (e.g. fuels). Energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. For example, a wind turbine transforms the kinetic energy of wind into electrical energy, and a car engine turns chemical energy in its fuel into kinetic energy to move. While various units are used depending on the type of energy discussed, the main unit of energy is the Joule.

Electricity: as noted above, electrical energy is a type of energy. Electricity results from charged particles that can either be static or flow as a current - e.g. to our homes. Electrical energy can easily be converted into other forms of energy, such as light in a lightbulb.

Power: in physics, energy is the capacity to do work, and power is the rate at which the work is done. The unit of power is the Watt, equal to one Joule per second. Electrical appliances have their power ratings represented in Watts (e.g. lightbulbs), and electrical generators (often known as power plants) have their capacity to generate measured in a magnitude of watts e.g. kilowatt KW (1000W) or megawatts MW (1000KW). This capacity is different from the actual electrical output or generation of the power plant which incorporates the power produced over a unit of time, resulting in the unit watt-hour (Wh). Most power plants do not operate at 100% capacity at all times for various reasons.

In energy policy, power tends to refer to electrical power. As such electricity and power are often used interchangeably, including in this paper. However, as set out above, energy and electricity should not be conflated.

In the UK, energy consumption has fluctuated significantly in the last 18 months with use falling by 19% to a record low in the second quarter of 2020 due to Covid-19, it has recently rebounded slightly, but remains 11% lower than in the first quarter of 2020 2. BP's Statistical Review of World Energy 2021 reveals that the pandemic has had a dramatic impact on energy markets, with both energy consumption and carbon emissions falling at their fastest rates since the Second World War 3:

Energy consumption fell by 4.5% in 2020; driven mainly by a decline in demand for oil, with gas and coal also experiencing significant drops

Capacity in wind, solar and hydroelectricity all grew despite the fall in overall energy demand

By country, the US, India and Russia experienced the largest declines in energy consumption. China accounted for the largest increase (2.1%), one of only a handful of countries where energy demand grew last year.

Most societies still rely predominantly on the availability of cheap fossil fuels to function. These however produce greenhouse gases (GHG), which it is now recognised, are unequivocally driving the climate emergency35:

Global carbon emissions from energy use fell by 6.3%, to their lowest level since 2011. As with energy, this was the largest decline since the end of World War II.

However, the International Energy Agency has recently warned that GHG emissions that have been "hollowed out by the COVID-19 pandemic are set to rebound in 2021 unless governments take swift policy action" 6.

In Scotland, total energy consumption has been steadily decreasing in recent years, and in 2019 it was 13.4% lower than the 2005-07 baseline. Scotland's total final energy consumption is dominated by demand for heat (51%), followed by transport (25%) and electricity (22%). Energy statistics are considered in more detail below.

In recent years, common approaches to energy management have centred on developing a framework which adequately encompasses all of the competing problems that energy policy must address. In 2019 the Royal Society of Edinburgh's (RSE) inquiry into Scotland's Energy Future reported 7:

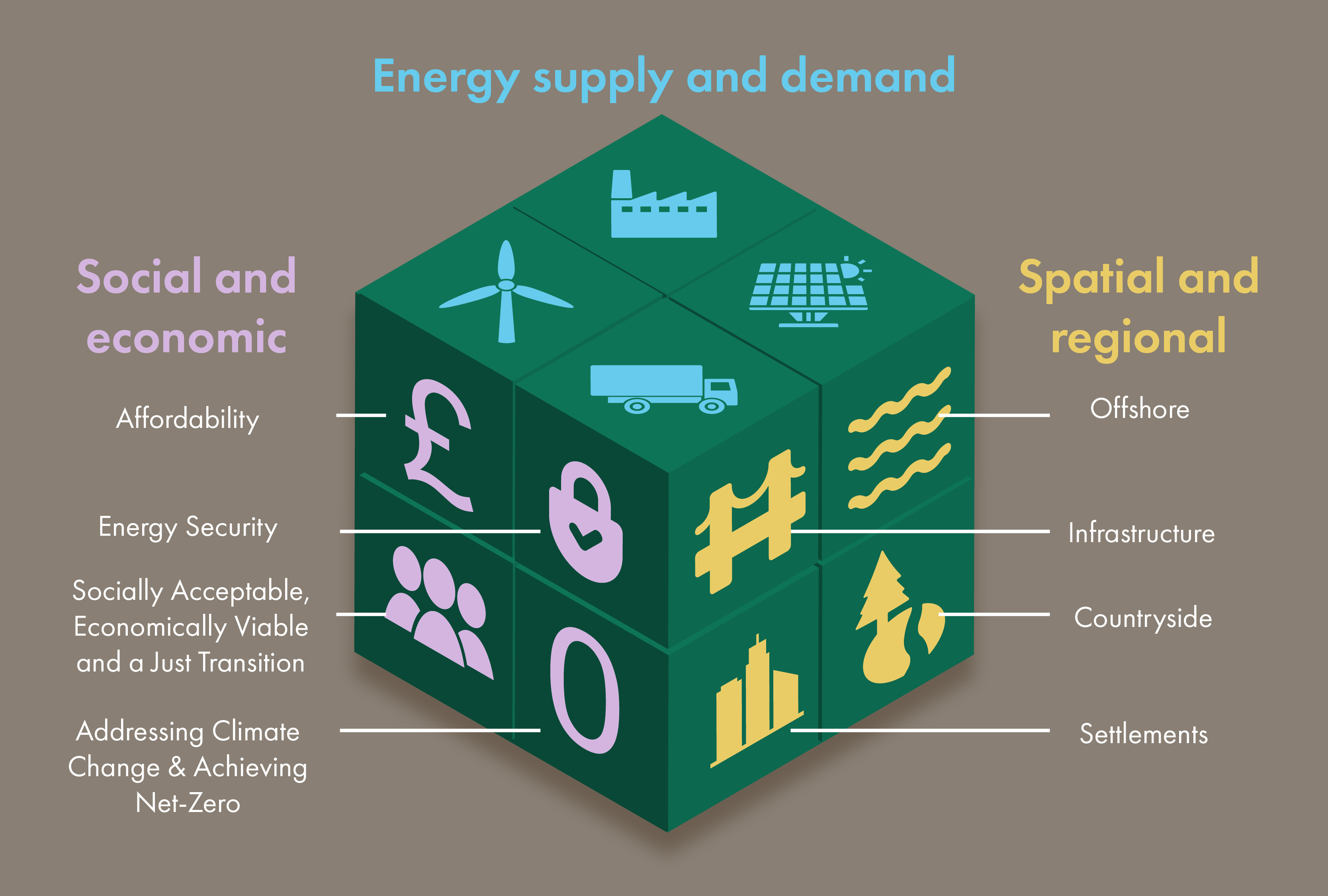

Those developing policy must ask how best to address the competing issues of the ‘energy quadrilemma’: addressing climate change; ensuring affordability; providing energy security; and developing energy policy which is acceptable to the public, economically sustainable and just.

Energy security relates to a country’s ability to meet its current and predicted energy demand.

The Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee's Energy Inquiry Findings from 2020 mirrored many of the RSE's, and recognised the challenges of "balancing competing issues", stating that "no energy policy, however well considered, can solve all of the paradoxes of energy demand and supply". A Rubik's Cube analogy was also used, likening the challenge to managing "horizontal (energy), vertical (industrial) and spatial (regional) positions", where policies and actions to address a pressing issue on one plane has the potential to have a detrimental impact on another. This "must be managed, if not mastered, by Scottish policy makers" 89.

In the coming parliamentary session, a rapidly changing and increasingly complex energy landscape will lead to multiple converging issues affecting the way that our settlements, cities, and houses are designed, operated and powered. The way that we choose to travel, live and interact can also significantly change energy use. This briefing provides an introduction.

Figure 1 shows the interaction between multiple competing issues:

Scotland's Energy Mix

This section provides an overview of Scotland's energy mix, and is based on information provided by the Scottish Government in the Scottish Energy Statistics Hub1 . This is an interactive tool, with commentary, for all Scottish energy data. Scotland's Energy Strategy, key sources and targets are explored in detail below.

As previously noted, Scotland's total final energy consumption is dominated by demand for heat (51%), followed by transport (25%) and electricity (22%). Demand for this energy in terms of its end use came predominantly from industry (33%), followed by the domestic sector (30%), transport (26%), and commercial (11%) in 2018.

Non -electrical energy for heat is still predominantly supplied by gas (57%), followed by petroleum products e.g. fuel oil (34%). Renewable energy for heat (e.g. from biomass or heat pumps) amounts to 7%.

Energy supply in the transport sector is dominated by fossil fuels, with 99% of all vehicles registered in Scotland reliant on petrol or diesel. The adoption of ultra-low emission vehicles (ULEVs) (predominantly electric cars) has however risen significantly in percentage terms at least, with a 63% rise in ULEV registration between 2019-2020. The SPICe Briefing Transport in Scotland: Subject Profile provides further detail.

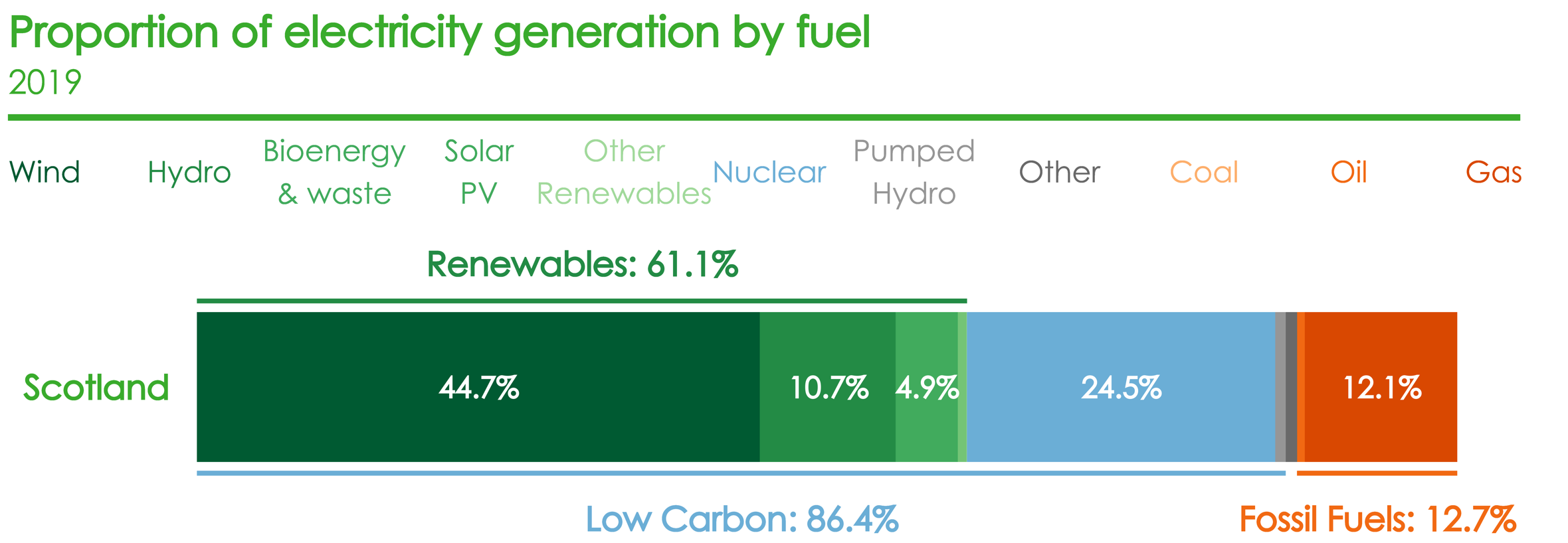

Scotland's electricity sector is predominantly powered by renewable generation (61%), followed by nucleari (25%), and with fossil fuelsii accounting for 13%. The primary technology for renewable generation is onshore wind (62%), followed by hydro (19%) and offshore wind (11%). Bioenergy, solar and wave/tidal make up the balance. Renewable generation more than tripled in the last decade - from 19% of all generation in 2010.

Scotland is part of a GB wide electricity grid and wholesale market, with the Moyle Interconnector linking to the Island of Ireland (which is one integrated single market), and the Western Link between Hunterston in South Ayrshire and Quay Bay in North Wales. Historically, Scotland has had a significant surplus of electricity generation over peak demand and has been a net exporter to Ireland and the rest of GB for over 20 years. In 2019, 32% of total Scottish electricity generation was exported.

Taking net electricity exports into account, the equivalent of 97.4% of gross electricity consumption came from renewable sources in 2020, rising from 89.5% in 2019.

Policy Context

Global

Energy is tradeable on world markets; indeed it drives global markets. Sources of energy for direct and indirect uses are positioned in particular geographical locations which bring considerable wealth to some areas, and make energy a politically and strategically sensitive and lucrative commodity. Scotland is very much involved in the world market. For instance:

North Sea oil and gas is traded globally, though imports are becoming more important

Scottish energy companies are part of larger energy groups, for example ScottishPower, one of Scotland's biggest electricity generators and suppliers, is owned by Spanish company Iberdrola

The European Marine Energy Centre in Orkney has tested technologies from companies based in Holland, Norway and many other countries

Mitsubishi Electric’s research and development headquarters are based in Livingston, one of only two European bases.

Addressing the environmental impacts of GHG emissions from fossil fuels (as well as other sources) is now an urgent concern, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has been instrumental in seeking global agreements to do this. Annual meetings on climate change (Conferences of the Parties (COP)) are held as part of this framework.

A number of global initiatives and commitments on climate change have been achieved under the UNFCCC to date; including in Kyoto in 1997, Cancún in 2010, Durban in 2011. The Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015 at COP21; key provisions are:

Global temperature rises should be limited to “well below” 2°C and to “pursue efforts” to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre industrial levels

Parties to the agreement are to aim to “reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible”

Parties are to take action to “preserve and enhance” carbon sinks

To conduct a “Global Stocktake” every five years, starting in 2023

Developed countries to provide financial support for developing countries to mitigate climate change

Creates a goal of “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change”.

The Agreement also requires all parties to prepare, communicate and maintain national GHG reduction targets. Known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) these should set out each party’s efforts to reduce national emissions, and are the basis for tracking action and alignment with targets. The Scottish Government recently published an Indicative NDC for Scotland.

The 26th United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP 26), to be held in Glasgow in November 2021, is the largest international negotiation ever to be held in the UK. This summit, chaired by the UK Government and held in partnership with Italy, aims to bring heads of state, climate experts and campaigners together to "accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change". Originally scheduled for November 2020, this is considered to be one of the most important climate conferences ever, with the talks widely considered to be the last opportunity to deliver on commitments to keep global temperature rise to within 1.5 – 2°C 123.

In light of these commitments, installing renewable energy technologies and reducing energy usage are seen as playing a key role in addressing climate change, and a number of studies into global energy supplies have been carried out 45. Most recently, the International Energy Agency's (IEA) Net Zero by 2050: a Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector notes that climate pledges by governments to date, even if fully achieved, would fall well short of what is required to bring GHG emissions to net zero by 2050 and give the world an even chance of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 °C. There is however 6:

a viable pathway to building a global energy sector with net-zero emissions in 2050, but it is narrow and requires an unprecedented transformation of how energy is produced, transported and used globally.

Near term actions include an "immediate and massive deployment of all available clean and efficient energy technologies, combined with a major global push to accelerate innovation". 2020 was a record year for the installation of solar and wind power, however this will have to quadruple by 2030. A major global "push to increase energy efficiency is also an essential part of these efforts, resulting in the global rate of energy efficiency improvements averaging 4% a year through 2030 – about three times the average over the last two decades" 6. Crucially the IEA's work has shown that the falling cost of windfarms and solar panels mean a significant majority of new renewable energy projects would undercut the cost of fossil fuel plants, and that replacing existing coal fired electricity production with unsubsidised renewable energy could save billions in energy system costs and avoid substantial GHG emissions. The IEA's work has also shown that from 2021 there should be no new oil and gas fields approved, and no new coal mines or mine extensions 8.

SPICe subject profiles on Climate Change and on COP26 provide further details 910.

Post-Brexit Framework

Membership of the EU required the United Kingdom to comply with European legislation in relation to energy policy. Indeed, the UK played a pivotal role in developing the key pillars on which EU policy is based; including energy efficiency, renewable energy, energy security, and integrated energy systems and markets. Having now left the EU, agreement on these matters can be found in:

UK-Euratom Nuclear Cooperation Agreement (an agreement for cooperation on the safe and peaceful uses of nuclear energy)

Revised Withdrawal Agreement (October 2019).

The TCA provides a new model for trading and interconnectivity, with guarantees for open and fair competition, including on safety standards for offshore, and production of renewable energy 1.

Norton Rose Fulbright, an international law firm states 2:

The UK’s energy networks remain physically connected to those of the EU. Trade over interconnectors is beneficial to both the UK and the EU, due to the lower costs to consumers of cheaper imports and the additional flexibility which interconnectors provide.

However 2:

The UK and the EU have not reached agreement on all aspects of their future energy relationship. The energy aspects of the TCA will terminate on 30 June 2026, although this may be extended [...] to 31 March 2028 at the latest. With issues such as trade over interconnectors and an enduring agreement with respect to the electricity sector in Northern Ireland, the UK is likely to be involved in energy negotiations with the EU for some time longer.

The EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is one of the cornerstones of the EU's climate change policy. It is the largest multi-country, multi-sector greenhouse gas emissions trading system in the world covering more than 11,000 power stations and industrial plants across EU Member states. Around 1,000 of those were in the UK until it left the EU and the EU ETS at the end of 2020.

Following a consultation and recommendations from the Climate Change Committee, a UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS) has replaced the EU ETS, and is of similar design and has similar aims to the former scheme.

The UK and devolved administrations aim to align it with the UK 2050 net zero targeti by 2024 at the latest. The TCA committed both parties to explore options for linking EU and UK schemes but does not go further.

The House of Commons Library Briefing Paper on The UK Emissions Trading Scheme provides further detail 4.

UK Policy Framework

Reserved and Devolved Aspects of Energy Policy

Energy matters are largely reserved under Schedule 5 Head D of the Scotland Act 1998. However, the Scottish Government has responsibility for the promotion of renewable energy generation, energy efficiency, and the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development. It has responsibility for the environmental impacts of energy infrastructure through planning controls. In addition, Scotland has a large part to play in helping the UK meet global climate change targets.

Whilst the "generation, transmission, distribution and supply of electricity" are reserved, planning consent is devolved; therefore applications to build and operate power stations and to install overhead power lines are made to Scottish Ministers. Applications are considered where they are:

For electricity generating stations in excess of 50 MW

For overhead power lines and associated infrastructure, as well as large gas and oil pipelines.

Applications cover new developments as well as modifications to existing developments. For developments below these thresholds, applications are made to the relevant local planning authority. For marine energy (e.g. wave, tidal and offshore wind), applications are made to Marine Scotland.

The Scotland Act 2016 devolves further powers in relation to energy; including the management of licences to exploit onshore oil and gas resources in Scotland, and powers over supplier obligations regarding energy efficiency to the Scottish Government. There is also a consultative role for the Scottish Government and Parliament regarding incentives to support renewable energy developments.

Radioactive waste is a devolved issue, and is regulated and managed by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA). Building standards and many areas of transport policy are also devolved, meaning that action can be taken by the Scottish Government to reduce demand across key areas of fossil fuel use.

UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a developing international framework. Policy areas and issues specifically relevant to Scotland are considered in the relevant section of this briefing, whilst those that are UK wide are considered below.

Energy policy in the UK is the responsibility of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Whilst there are other sector specific regulators, much of the energy market is regulated by the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem).

Historically, parts of energy generation, transportation, and supply were run by the public sector. Most of the market is now privatised; generation and supply are competitive, and transportation through networks is regulated as the operators are monopolies.

The UK Government and Ofgem continue to regulate the market for customers, and deliver policy to meet policy aims on energy.

As previously noted, the UK has a target to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050. This was enshrined in law by amendment to the Climate Change Act 2008. A suite of Energy Acts have shaped UK policy over the years, most recently:

The Energy Act 2013: puts in place electricity market reform (EMR). This was designed to decarbonise electricity generation, keep the lights on, and minimise the cost of electricity to consumers. The most significant changes have been the creation of the capacity market and the implementation of contracts for difference (CfD) for renewables, to replace the renewables obligation. These are discussed in more detail below

The Energy Act 2016: Created a new Oil and Gas Authority, meaning that a quango rather than a government minister regulates the oil and gas industry, with a remit to "maximise the economic recovery of the UK’s oil and gas resources, whilst also supporting the move to net zero carbon by 2050".

In November 2020 the UK Government published a Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, with a focus on English and UK wide policy areas, including the following 1:

Delivering new and advanced nuclear power

Accelerating the shift to zero emission vehicles

‘Jet zero’ and green ships

Investing in carbon capture, usage and storage

Green finance and innovation.

The UK Government states 1:

The ten point plan will mobilise £12 billion of government investment, and potentially 3 times as much from the private sector, to create and support up to 250,000 green jobs.

In December 2020 the UK Government published the Energy White Paper. This built on the Ten Point Plan, and contains new policies and details, with chapters on consumers, power, energy system (including transport) building, industrial energy, and oil and gas 3.

Further details are expected in the coming months as the Energy White Paper has promised various sector-specific strategies and consultations. In addition, the UK Government will publish an overarching net-zero strategy before COP26 in November 2021. Policy alignment between the UK and Scottish Governments will be crucial to achieving energy and emissions reduction targets, particularly in relation to heat in buildings and hydrogen.

The House of Commons Library Briefing Paper on Energy Policy and Overview provides further detail 4.

Fossil Fuels

While their role in electricity generation has reduced significantly over the last ten years, fossil fuels remain the largest part of Scotland's energy consumption, accounting for 76.1% in 2019. Fossil fuel extraction also contributes significantly to economic activity and employment in Scotland. This section will look at the policy context and key issues for oil and gas, coal and hydrogen.

Hydrogen might at first glance appear out of place, but at present the vast majority (96%) of hydrogen production involves fossil fuels.

Oil and Gas

The oil and gas industry makes a significant contribution to Scotland's economy and labour market, particularly in the North East. In 2019, Scotland (including Scottish adjacent waters) produced an estimated 54.0 million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) of crude oil and natural gas liquids (NGLs) (equivalent to 628 TWh). While this is approximately 40% of its peak in 1999, it is an increase of 2.2% on 2018. Production across the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) has increased steadily since 2014 following several years of substantial investment in the development of new and existing fields. Scotland accounts for 95.2% of total UK crude oil and NGLs production.

Scotland produced 23.2 mtoe of natural gas in 2018 (equivalent to 270 TWh), although this has dropped for each of the last three years. It accounts for 62.1% of total UK gas production. This is the equivalent of almost six times Scotland’s gas consumption.

While the licensing related to offshore developments is a reserved matter, onshore oil and gas licensing powers were devolved to the Scottish Parliament as part of the Scotland Act 2016.Onshore oil and gas is often referred to as 'fracking'. Commencement of sections 47 to 49 of the Scotland Act 2016 transferred powers to:

Legislate for the granting and regulation of onshore licences

Determine the terms and conditions of licences

Regulate the licensing process, including administration of existing onshore licences.

On 3 October 2019 the Scottish Government set out its policy position that onshore oil and gas extraction was incompatible with climate policy, and that the Scottish Government would not issue licences for new extraction.

Scottish Government policy attempts to recognise the key contributions the sector makes to the Scottish economy while highlighting the challenge this poses to the climate emergency. In the 2018-19 programme for government 1, the Scottish Government confirmed that support for oil and gas exploration will be conditional on the sectors actions to help ensure a sustainable energy transition. Key policies include:

Supporting the development of carbon capture, utilisation and storage technology through working with industry to support small scale demonstration projects, and ensuring that critical infrastructure such as oil and gas pipelines are retained

Supporting hydrogen technology through funding hydrogen buses in Aberdeen since 2013, and the Surf n Turf project in Orkney. More information on hydrogen policy is available later in this briefing

Establishing the Transition Training Fund in 2016 to support the highlight skilled workforce in the North East of Scotland region

Running the Decommissioning Challenge Fund which aims to support the upgrading of infrastructure and development of the Scottish supply chain.

The Cambo Oil Field

The Cambo oil field is a proposed development west of the Shetland Islands which contains over 800 million barrels of oil. Exploratory work began in the area as early as 2001. The UK Oil and Gas Authority are due to make a decision on the granting on licenses for drilling, and if given the green light drilling could start in 2022, and could produce oil and gas for 25 years.

Opponents of the development of the field highlight that extracting more oil from Scottish waters in the same year as the country hosts COP26 could lead to accusations of hypocrisy, while proponents highlight the ongoing need for fossil fuels as the economy transitions to net zero, and the benefits this development could bring to UK public finances and local businesses.

As noted above, offshore licensing is a reserved policy area. However, the First Minister wrote to the Prime Minister on the development of the new oil field urging him to re-examine the proposals due to the climate emergency. The First Minister called for enhancements to the climate conditionality associated with offshore oil

Coal

Coal production in Scotland stands at 0.4 million tonnes in 2019, down by 33.2% on 2018 to its lowest point to date. Employment in the coal sector in Scotland however rose by 19.2% between 2018 and 2019 to 87, though this is still down 45.3% from 2017.

The House of Commons Library noted that demand for coal is at a record low because of the falling demand for its use in electricity generation, with demand for coal down by 87% since 2013 1. In addition to its use in electricity generation, coal is used in steel manufacturing. The majority of UK steel production used the blast furnace which relies on coke - a type of coal.

The UK Coal Authority remains responsible for all coal exploration licences on behalf of the UK Government, however Scottish Ministers ultimately have a veto on any developments in Scotland through planning applications.

Cumbria coal mine

In October 2020 Cumbria Council granted permission for a new coal mine near Whitehaven. This was met with considerable backlash from environmental groups. The Climate Change Committee have argued that up to 85% of the coal produced would be exported2, and that every extra tonne of coal on the world market will drive down the price and drive up emissions. Proponents of the mine argue that the £160m investment will bring quality jobs to the area, and that the coal is needed for the UK steel industry. In March 2021 the UK Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government ordered a public enquiry into the proposal.

Hydrogen

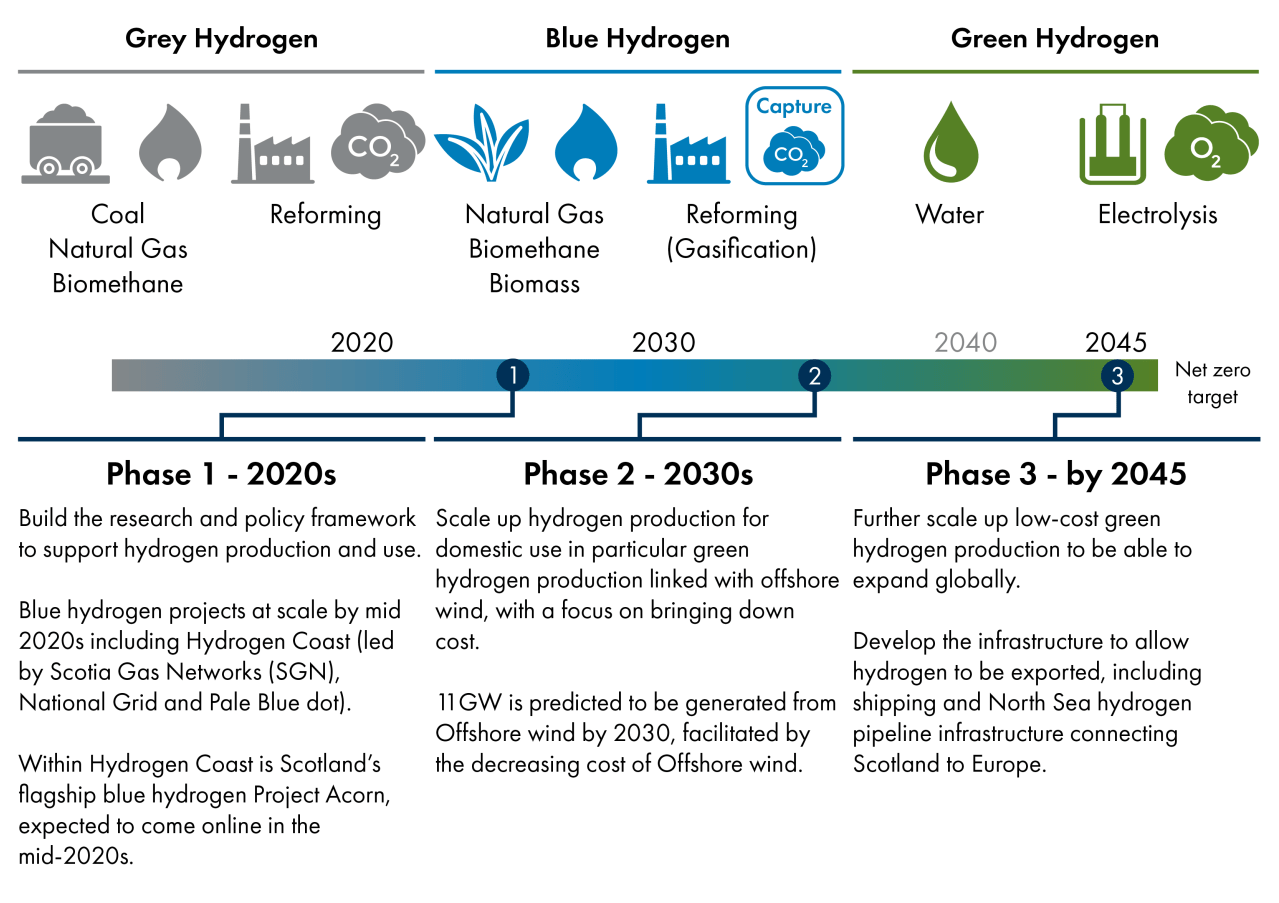

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and can be used as a fuel, an energy carrier and store. Hydrogen does not release carbon when burned and therefore it has the potential to cut carbon emissions across a range of energy-intensive sectors, including transport, industry and heat generation. However, the use (and environmental impact) of hydrogen as a zero-carbon fuel depends on how it is produced, as hydrogen does not exist naturally in large quantities on Earth and must therefore be manufactured.

There are broadly three ways to manufacture hydrogen. Currently, the most common way uses fossil fuels, and a process known as steam reforming, which releases carbon. This is referred to as 'grey hydrogen'. Low or zero-carbon methods do exist, but these rely on technologies which are still under development in Scotland and require considerable amounts of low-cost renewable energy. These are known as 'blue hydrogen' and 'green hydrogen'. The potential role of hydrogen in decarbonisation is explored in further detail in the following SPICe Blogs:

Can hydrogen drive Scotland to net-zero? Part 1: What is hydrogen energy?

Can hydrogen drive Scotland to net-zero? Part 2: What are Scotland’s hydrogen energy plans?

In December 2020, the Scottish Government published its Hydrogen Policy Statement which sets out how Scotland’s natural resources, skills and supply chain may offer the potential for large-scale hydrogen production — with a £100 million commitment in funding for research and innovation development between 2021 and 2026. The statement highlights Scotland’s potential for generating green, zero-carbon hydrogen from offshore wind, and the repurposing of oil and gas pipeline infrastructure for hydrogen export to Europe.

The Policy Statement outlines three key phases in the Scottish Government’s proposed transition to a hydrogen-based energy economy — beginning with investment in blue hydrogen projects in the 2020s and eventually building up to green hydrogen production at scale by the 2045 net-zero target. Further detail is outlined in Figure 2 below. A more specific time frame for each of the phases is expected to be published later this year in the follow-up Hydrogen Action Plan.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) considers that hydrogen is a credible option to help decarbonise the UK energy system, but will require Government commitment and improved support to develop the UK's industrial capacity. Hydrogen could replace natural gas in parts of the energy system (areas where electrification is not feasible or too expensive such as high temperature industrial processes and bulk transport). The CCC notes that a balanced pathway to net zero would see the hydrogen economy develop from virtually zero use in the energy system today, to a scale that is comparable with present day electricity use between 2030 and 2050, but focused on particular applications, rather than as a mainstream technology for home heating.

The Nuclear Option

Nuclear power has been part of GB's electricity generating mix for over 50 years. In the 1990s, 30% of electricity output was from nuclear power. However, as stations have grown older and some have closed, the contribution of nuclear power has declined. There are currently seven nuclear stations across England, Scotland and Wales providing around 15% of electricity consumed 1.

Following years of cancellation or postponement of various new nuclear projects, two reactors are currently being built at Hinkley Point C in Somerset 2.

The UK Government's Energy White Paper notes that with the exception of Sizewell B and the plant under construction at Hinkley, all of GB's existing nuclear plants are due to have closed by the end of 2030. A commitment to ending electricity generation by coal in 2024 means that the UK Government supports the construction of new nuclear, and states 3:

Nuclear power provides a reliable source of low-carbon electricity. We are pursuing large-scale nuclear, whilst also looking to the future of nuclear power in the UK through further investment in Small Modular Reactors and Advanced Modular Reactors.

Scotland has two EDF-owned nuclear stations currently generating electricity: Hunterston B and Torness; and three Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA)-owned civil nuclear sites at advanced stages of decommissioning: Dounreay, Chapelcross and Hunterston A.

As set out on in the section on UK Policy Framework, Scottish Ministers have powers to consent all power stations over 50MW. The Scottish Government states:

We recognise the significant contribution that nuclear generation makes to the current energy mix in Scotland; however, we expect its contribution will decrease as we increase electricity generation from renewable and other low carbon sources.

Therefore, the Scottish Government remains opposed to new nuclear stations, under current technologies 4. As previously noted, radioactive waste is a devolved issue, and is regulated and managed by SEPA.

New technologies e.g. Small Modular Reactors and Advanced Modular Reactors will be assessed "based on safety, value for consumers, and contribution to Scotland’s low-carbon economy and energy future" 4.

Supporting Low Carbon Electricity Generation

As previously noted, the Scottish Government has responsibility for the promotion of renewable energy generation, however fiscal support for renewables is set by BEIS, and designed in line with achieving decarbonised electricity generation, ensuring energy security and minimising costs to consumers.

Large Scale Generation

Up to 2017, the Renewables Obligation (RO) was the main support scheme for renewable electricity projects in the UK.

It placed an obligation on UK suppliers of electricity to source an increasing proportion of their electricity from renewable sources. A Renewables Obligation Certificate (ROC) was issued to an accredited generator for renewable electricity generated and supplied to customers. Different technologies attracted differing numbers of ROCs per megawatt hour of renewable output, depending on commercial viability e.g. onshore wind received 0.9 ROCs, whilst tidal stream and wave technology received 5.

Suppliers met their obligations by presenting sufficient ROCs. Where suppliers did not have sufficient ROCs to meet their obligations, they paid an equivalent amount into a fund, the proceeds of which were paid back to those suppliers that have presented ROCs. Under EMR, the RO closed to new entrants from all technologies in 2017, however the scheme will continue to operate for existing participants until 2037.

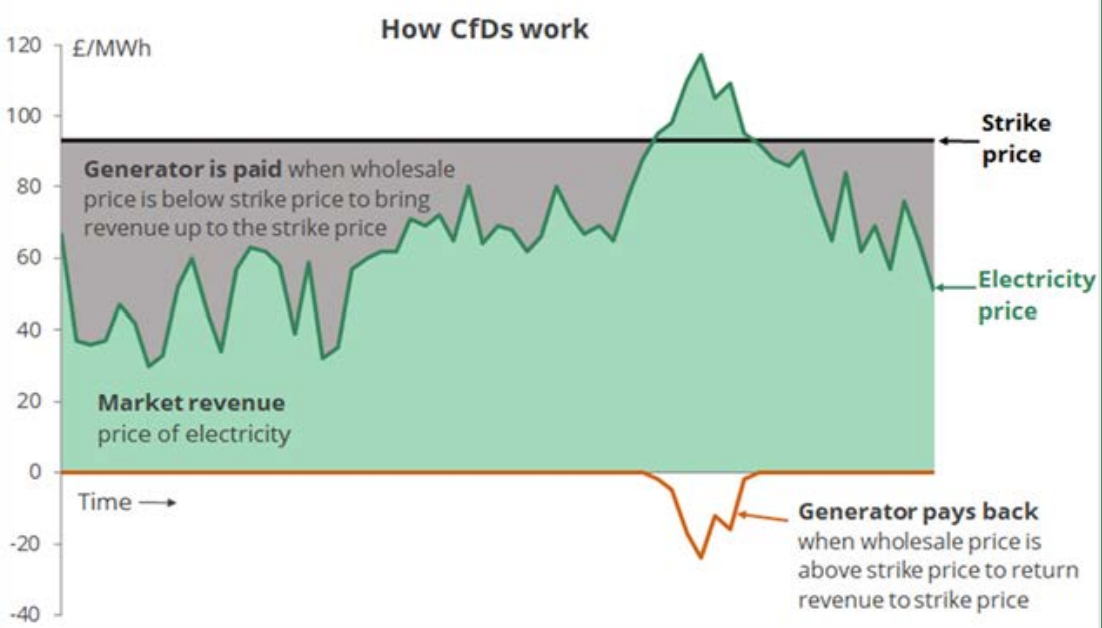

Large scale, low carbon power infrastructure (including new nuclear) is now supported through Contracts for Difference (CfD). Introduced in 2013 as part of a number of changes under EMR, CfDs work by fixing the prices received by low carbon generation over a number of years, reducing the risks developers face from a fluctuating wholesale power price, and ensuring that eligible technology receives a price for generated power that supports investment. The fixed price is known as the strike price.

A CfD is a private law contract between a low-carbon electricity generator and the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC), a UK Government-owned company. Under the CfDs, when the market price for electricity generated by a CfD Generator is below the strike price set out in the contract, payments are made by the LCCC to the CfD Generator to make up the difference. However, when the market price is above the strike price, the CfD Generator pays LCCC the difference. This is shown in Figure 3 below:

The payments, and repayments, paid and received by the LCCC for the CfD scheme are passed on to consumer electricity bills.

CfDs are mostly decided at auctions, known as allocation rounds, to allow competition between technologies and help keep prices low. The Government sets a budget in advance, then sealed bids of strike prices submitted by developers are accepted sequentially from the lowest to the highest until the budget is exceeded.

Three allocation rounds have taken place to date, most recently in 2019, with a fourth expected to open in December 2021 1. CfD funding has been set out in ‘Pots’ which group the technologies that can compete:

Pot 1 is "established technologies" including Onshore wind, Solar Photovoltaic (PV), Energy from Waste with combined heat and power (CHP), Hydro, Landfill Gas and Sewage Gas

Pot 2 is "less established technologies" including Offshore Wind, Remote Island Wind (added for 2019 auction), Anaerobic Digestion, Wave, Tidal Stream, and Geothermal.

Allocation rounds two and three have focussed solely on Pot 2 technologies, however the forthcoming allocation will include established technologies, as well as creating a new Pot (3) solely for offshore wind projects, which will now compete between themselves 1.

Since the first allocation round in 2014, the strike price has steadily fallen from over £100/MWh to around £40/MWh, depending on technology with the most significant change being the dramatic reductions in the offshore wind CfD. It is however not possible to directly compare the costs of different energy technologies based solely on strike prices for several reasons:

Contract lengths vary (15 years for for wind vs 35 years for nuclear)

Total length of operation (hydro can generate for 100+ years)

The capacity (MW) and the load factor (how often it generates) of the technologies vary

The cost of integrating different technologies into the grid varies, i.e. in terms of grid connection costs, and system balancing.

Levelised Electricity Generation Costs are calculated and explored in more detail by BEIS 3.

The House of Commons Library Briefing Paper on Support for Low Carbon Power provides further detail 4.

Small Scale Generation

Introduced in 2010, the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) scheme promoted the uptake of small scale renewable electricity generation such as solar PV and small wind turbines. Participants in the scheme received three benefits:

Generation tariff - payment from electricity supplier for units of power generated

Export tariff - payment from supplier for any surplus units of generated power that instead of being consumed on site, are exported to the grid

Possible lower electricity bills - as producers consume their generated power.

This scheme is considered to have been successful, with nearly 850,000 installations (mostly solar PV), far more than originally expected. High uptake has led to higher costs; the UK Government say the scheme has cost £6 billion so far and will total £30 billion over the scheme’s life1. In December 2018 the UK Government announced that the FiT would close as “it does not align with the wider government objectives to move towards market-based solutions, cost reflective pricing and the continued drive to minimise support costs on consumers”. The changes only impact new installations after the end of March 2019; existing installations will continue to be paid as usual 2.

Closing the FIT scheme meant not only that there are no subsidies for installing small-scale renewables, but that those that did install renewables would be exporting any surplus power to the grid for free. Therefore, from January 2020 a Smart Export Guarantee (SEG) has been in place; this requires electricity suppliers to offer a tariff for the surplus power that renewable generators export to the grid, and is available for technologies up to a capacity of 5MW, including solar PV, hydro, and wind.

The House of Commons Library Briefing Paper on Support for Small Scale Renewables provides further detail 3.

Supporting Renewable Heat

Since 2011, support known as the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) has been available to non-domestic customers (and from 2014 for domestic customers) to install renewable heat generating technologies. e.g. biomass boilers, solar water heating and heat pumps. The RHI operates in a similar manner to the FiTs, and payments are based on the amount of renewable heat generated by the system.

The UK Government has confirmed that the RHI will close in March 2022, to be replaced by the Clean Heat Grant. This grant is directed towards households and small non–domestic buildings, and aims to help with the upfront installation cost of heat pumps which provide space heating and hot water. Larger non-domestic buildings and companies will not be eligible 1.

Retail Markets and Affordability

The current UK Government's position is to promote competition in the wholesale and retail markets.

Most recently, Ofgem asked the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to conduct an Energy Market Investigation in June 20141. In referring the matter to the CMA it was intended to be a once and for all investigation as to whether or not there are further barriers to effective competition, because the CMA has more extensive powers that can address any long-term structural barriers to competition. This concluded in June 2016 and reported 2:

[…] that 70% of domestic customers of the 6 largest energy firms are still on an expensive ‘default’ standard variable tariff. As these customers could potentially save over £300 by switching to a cheaper deal, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) will be enabling more of them to take advantage. The CMA has found that customers have been paying £1.4 billion a year more than they would in a fully competitive market.

The CMA report also highlighted that affordability is a key issue in the retail energy market, noting that:

Energy is a necessity, and that energy prices are regressive. The poorest 10% of the population spend almost 10% of total household expenditure on electricity and has, while the richest 10% spend around 3% of total household expenditure.

The CMA proposed over 30 measures, including ordering suppliers to give Ofgem details of all customers who have been on their default tariff for more than 3 years, as well as introducing a price cap for customers on pre-payment metres. Citizens Advice research highlights that customers on pre-pay meters tend to be on lower incomes, and face higher costs than customers on direct debits deals 3.

A wider tariff cap was a key issue in the 2017 General Election, and on 1 January 2019 the Domestic Gas and Electricity (Tariff Cap) Act 2018 came into force. The cap has been extended to 2023, and the Government plans to extend it further. Ofgem have announced that the price cap will be increased by £139 from 1 October 2021, driven by the increase in energy costs. Measures introduced following the CMA report in 2016 appear to have increased levels of switching in the retail market; the House of Commons Library notes that in 2012, the big 6 suppliers were responsible for over 95% of the domestic energy market, but this has declined to about 70% as at Q4 2020. Ofgem notes that in 2019 the level of switching in the market was the highest recorded since 2003 4.

Demand Reduction

Energy efficiency, and high energy prices, link directly with health and well-being. This section sets out key areas of UK Government action in relation to demand reduction.

Addressing fuel poverty is however devolved, further information on addressing this and demand reduction in a Scottish context is set out in the relevant section. The Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act 2019 defines the issue as follows 1:

A household is in fuel poverty if the household’s fuel costs (necessary to meet the requisite temperature and amount of hours as well as other reasonable fuel needs) are more than 10% of the household’s adjusted net income and after deducting these fuel costs, benefits received for a care need or disability, childcare costs, the household’s remaining income is not enough to maintain an acceptable standard of living.

[...]

The requisite temperature and amount of hours is defined as:

For households requiring an enhanced heating regime, this would be 23°C in the living room and 20°C in other rooms. For other households, this is 21°C in the living room and 18°C in other rooms. For a household for which enhanced heating hours is appropriate, heating the home to the requisite temperatures for 16 hours a day, every day. For any other household, heating the home to the requisite temperatures for 9 hours a day on a weekday and 16 hours a day at the weekend. “Net income” means the income of all adults in the household after deduction of income tax and national insurance contributions.

UK wide measures designed to help consumers with their energy bills include:

Taxpayer-funded payments principally the Winter Fuel Payment and the Cold Weather Payment

Obligations on energy suppliers that are funded by all energy bill payers, principally to help vulnerable customers and those on low incomes with energy efficiency measures (Energy Company Obligation) and discounts on electricity bills (Warm Home Discount).

Energy saving and other energy advice services.

There are three key sectors where demand reduction is imperative and Table 1 sets out the main actions in these areas at a UK level; some of these require partnership working with the Scottish Government.

| Sector | Key Actions |

|---|---|

| Business | Market mechanisms to reduce GHG emissions – including the UK ETS for larger organisations, and other environmental taxes, reliefs and schemes for smaller private companies and public bodies.The UK has around 1,000 ETS participants (with around 100 of these in Scotland); at present around 30-40% of total UK emissions come from these sources. The scheme is being established with 5% fewer allowances in circulation than the UK had under the EU scheme, and the UK Government's recent Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy undertakes to align the ETS with net zero by 2024 2. |

| Domestic | The Energy Company Obligation (ECO), introduced in 2013, requires energy suppliers to "promote measures which improve the ability of low income, fuel poor and vulnerable households to heat their homes. This includes actions that result in heating savings, such as the replacement of a broken heating system or the upgrade of an inefficient heating system" 3.The Scotland Act 2016 devolves the powers to design how such ‘supplier obligation’ schemes are implemented; further information on Scotland’s approach can be found below. |

| Transport | Inclusion of aviation in the ETS, and support for electric vehicles. |

Transport

In 2019, GHG emissions from transport were responsible for 27% of the UK's total. Transport remains the largest emitting sector, with figures only 4.6% lower than in 1990, as increased road traffic and larger and heavier vehicle designs has largely offset improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency 1. Addressing emissions from transport by shifting to low carbon modes is therefore considered to be of paramount importance.

For reserved policy areas, the UK Government's Transport Decarbonisation Plan 2 commits to:

Plot a course to net zero for the UK domestic maritime sector, with indicative targets from 2030 and net zero as early as is feasible

Consult on a "Jet Zero" strategy, which will set out the steps to reach net zero aviation emissions by 2050.

The SPICe Briefing Transport in Scotland: Subject Profile provides further detail.

Scotland

As previously noted, UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a global framework. The promotion of renewable energy, the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development, promotion of energy efficiency, and powers over supplier obligations regarding energy efficiency are all devolved, allowing considerable attention to be focussed on advancing research, development and deployment in these key areas, and giving Scottish Ministers some powers in governing the overall energy mix, including nuclear generation via consenting powers. The Scottish Government recognises that ongoing collaboration with the UK Government and the GB energy regulator (Ofgem) and System Operator (National Grid) is fundamentally important, and states 1:

Achieving our aims will involve energy and non-energy policy levers, and a combination of reserved and devolved powers. Certain aspects [...], are matters for the Scottish Government and Parliament, while others – such as market support for different forms of power generation, and regulation of the gas and electricity grids – are reserved to the UK Government

Climate Change

Whilst climate change mitigation and adaptation policy is devolved to Scotland, the UK is signatory to international treaties, and has set an overall target of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

Following independent advice from the UK Climate Change Committee, the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 sets a target (against a 1990 baseline) of net-zero emissions by 2045, with crucial interim targets of a 75% reduction by 2030, and 90% by 2040. Annual targets are also set, and Scotland has not achieved these in the last three years (2017 - 2019), with the most recent statistics showing a 51.5% reduction in emissions against a target of 55%.

The Scottish Government regularly publishes Climate Change Plans (CCP) - required by law - which set out how emissions will be reduced across key sectors. An update to the current CCP was published in late 2020 to set out a pathway to net-zero; this anticipates a 56% reduction in emissions by 2032.

Scotland has slightly more than halved it's GHG emissions in the last 30 years, but this has relied mostly on the lowest cost forms of abatement, particularly changes in energy supply. It will have to more than half them again in the next decade to come close to achieving domestic targets, and contribute to achieving UK and international goals. The "hard yards" of decarbonisation will therefore fall within this parliamentary session, and will require detailed, strategic and co-ordinated scrutiny across multiple portfolios.

This pressing need to decarbonise drives and sculpts Scotland's energy policy, and is explored in more detail in SPICe Briefing Climate Change - Subject Profile.

Scotland's Energy Strategy

The future of energy in Scotland: Scottish energy strategy was published in 2017 1, and is expected to be updated before the end of 2021 to reflect the net zero 2045 target, and to include a Just Transition Plan for the sector. This sets out a 2050 vision for energy in Scotland, as follows:

A flourishing, competitive local and national energy sector, delivering secure, affordable, clean energy for Scotland's households, communities and businesses.

Based on three core principles 1:

A whole-system view: examining where energy comes from and how it is used – for power (electricity), heat and transport. This approach recognises the interactions and effects that the elements of the energy system have on each other. The Energy Efficient Scotland programme is considered to be the cornerstone of this approach, and is set out in more detail below

An inclusive energy transition: driven by the need to decarbonise the whole energy system, in line with net zero commitments, this transition to a low carbon economy must also be a "just transition" to tackle inequality and poverty, and to promote a fair and inclusive jobs market

A smarter local energy model: a smarter, more coordinated approach to planning and meeting distinct local needs by linking local generation/use and developing local energy economies. "Heat, electricity, transport and energy storage technologies – planned and deployed on an area-by-area basis – can transform both rural and urban communities".

Alongside, or stemming from the Energy Strategy, a number of further documents have been published, including:

Other relevant strategies are set out below.

Key Targets

As previously noted, the Scottish Energy Statistics Hub1 is an interactive tool, with commentary, for all Scottish energy data. A target tracker shows progress against key targets, as follows:

All Energy

The equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland's heat, transport and electricity use is expected to come from renewable sources by 2030. The Hub states 1:

Scotland's renewable energy target is calculated by the sum of renewable electricity and heat generation and estimated biofuel use in transport in Scotland, divided by Scotland's gross electricity consumption, non-electrical heat demand and energy used for transport. Therefore, progress towards the target will come from increasing renewable generation and reducing energy consumption.

Provisionally, in 2019, the equivalent of 24% of total Scottish energy consumption came from renewable sources, an increase of 2.9% from 2018.

Productivity

A 2030 energy productivity target aims to see a 30% increase in energy productivity from a 2015 baseline. This is measured as the % change in gross value added achieved from the input of one gigawatt hour of energy. The Hub states 1:

Higher energy productivity means you get more economic activity for each unit of energy used, in other words, squeezing more value added out of every unit of energy consumed across the economy.

Energy productivity in 2019 was 3.2% above the baseline. Compared to 2018, energy productivity improved by 1.3% , due to a 0.5% decrease in consumption and a 0.8% growth in GVA.

Renewable Electricity

A target to generate the equivalent of 100% of Scotland’s own electricity demand from renewable sources by 2020 has been narrowly missed. With provisional figures indicating that the equivalent of 97.4% of gross electricity consumptioni was from renewable sources, rising from 89.5% in 2019.

Renewable Heat

The renewable heat target is for 11% of non-electrical heat demand to come from renewables by 2020; in 2019 it was 6.5%. The Hub states 1:

Scotland generated 5,205 GWh of renewable heat in 2019 [...]. This is the equivalent of supplying almost 380,000 Scottish homes with gas for the year.

Energy Consumption

An energy consumption target to reduce Scottish final energy consumption by 12% by 2020 from a 2005 - 2007 baseline was met in 2013, with a record low of energy consumption in 2015 of 14.0% below the baseline. This has remained largely steady, and is currently 13.4% lower.

The Scottish Government also publishes annual energy statements, most recently in December 2020, to show progress against targets and to highlight key developments 5.

Key Issues and Scrutiny of Scotland's Approach

In 2017, The Parliament's Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee (EEFW) scrutinised Scotland's Energy Strategy, and evidence widely commended the "whole-system approach", however it was considered to be "strong on direction but not delivery", and more detail was called for, including 1:

key decision points anticipated over its lifespan and where ownership of those decisions lie, road maps for all the sectors (heat and transport as well as power), demand reduction (a significant policy area over which the Scottish Government has control), the modelling or analysis underpinning the renewables target, and public engagement.

One of the recurring themes of EEFW's Session 5 scrutiny of energy policy was the "scale and complexity" of the issues, and the need for strategic oversight; the need for an independent energy agency was therefore proposed:

[...] it will be important to ensure good governance, policy expertise, cross-party buy-in (as there has been for climate change) and long-term ownership. Sitting on the edge of a few civil servants’ desks, we were told, will not be enough. This is a strategy the lifespan of which extends beyond the usual electoral and budgetary cycles. The Committee on Climate Change was mentioned, as was the Danish Energy Agency, and the model of Transport Scotland for large infrastructure projects. Another witness underlined the importance of a body to spot problems before they became “a matter of post hoc accountability”. In the interests of ensuring continuity of delivery for the strategy, the Committee recommends a long term framework be put in place; one which could include the establishment of an independent body.

Consideration of a proposed Publicly Owned Energy Company (POEC) was carried out in 2018, which the Committee concluded could support the creation of new energy infrastructure, accelerate wider energy system transformation, increase engagement and participation in the energy system and reduce costs to consumers; however "simply supplying energy in an already crowded retail market would not be enough". The Committee also returned to the need for independent oversight 2:

We believe the POEC should become that independent body, one that can provide oversight, continuity and a long-term framework. Our concern is that, if the POEC is too focused on market entry and supply and possibly generation, the strategic dimension would be lost or diminished.

Between April 2019 and March 2021, the Committee scrutinised the management of and government involvement in Burntisland Fabrications (BiFab) who produce fabrications for the offshore oil, gas and renewables industry from their 3 yards in Scotland. In particular, they were interested in why BiFab had failed to gain contracts from recent offshore wind projects in Scotland, the role of the Scottish Government, and the role of CfDs and the UK Government. Committee conclusions were detailed and varied, and covered reserved and devolved aspects of energy policy, competition law, enterprise agency support, environmental and fair work considerations, and ongoing strategy 3.

The final Energy Inquiry of the session (2020) was carried out in three parts, linking an overview of the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Future Energy Report with consideration of electric vehicle infrastructure, and locally owned energy. Again, conclusions were detailed and varied, with recommendations for the Scottish Government, Transport Scotland, COSLA and Ofgem in relation to rapidly evolving energy systems and markets. In line with RSE's primary recommendation, and returning to a previous theme, the Committee considered that 4:

an independent expert advisory commission on energy policy and governance for Scotland should be established under statute – and with reference to our own previous work, we return to our recommendation that a long term strategic framework be put in place; one which could include the establishment of such an independent body. The foundations for such a framework must be built on good governance, policy expertise, cross-party buy-in (as has been the case for climate change), a whole systems approach, and long-term ownership.

The Climate Change Committee's 2020 Progress Report to the Scottish Parliament has called for the Scottish Government to 5:

Set out a vision for the future of low-carbon heating in Scotland’s homes and other buildings, integrated with UK Government decisions on the future of the UK gas grid and energy taxation

Make it easy for people to walk, cycle, use public transport, and work from home in Scotland, and ensure electric vehicle charging infrastructure and other enabling measures are in place to eliminate the need to buy a petrol or diesel car in Scotland by 2032 at the latest

Accelerate investments in low-carbon and climate adaptation infrastructure to stimulate Scotland’s economy, build long-term productive capacity and improve climate resilience

Engage with people and businesses in Scotland to develop skills for the net- zero transition, help people understand what the transition means for their lives, and make it easy to make low-carbon choices.

Renewables

Scotland is widely recognised as a world leader in renewable energy, with an abundance of renewable resources including wind, wave, tidal, hydro and biomass.

Scotland's target to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2045 will require the near complete decarbonisation of energy systems, with renewables meeting a significant share of national requirements. A growing and increasingly decarbonised electricity sector is therefore critical to enabling other energy intensive sectors to decarbonise e.g. transport, buildings and industry.

This section explores Scotland's approach to transitioning to a decarbonised energy system.

Supply Chain

The Scottish Government have long sought to support and strengthen the Scottish supply chain for renewable technologies, but this has proved to be a challenging aim. In the March 2021 Energy Strategy position paper the Scottish Government acknowledges this, stating that:

We recognise that the supply chain in Scotland has been missing out on lucrative offshore wind manufacturing contracts. This has been a challenge for some time, but has reached a point that has led to great frustration within Government, Parliament and across civic Scotland.

Scottish Renewables publish annual supply chain impact reports which give a snapshot of developments in the offshore wind supply chain, noting that in their view the 2020 report is ‘more impressive than ever’ as firms aim to support the Scottish Government objective of 11GW of offshore deployment in Scottish waters by 2030.

As previously noted, the Session 5 Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee conducted an inquiry on BiFab, the offshore wind sector and the Scottish supply chain. While this report does focus to an extent on the issues surrounding the administration of BiFab, it also notes many issues in relation to the Scottish supply chain. Central to several of these recommendations are the changed constitutional arrangements now that the UK has left the EU, and what this means in relation to state aid rules which may have previously held back government support, noting that:

The UK Government's aim is to have 60% UK content in the offshore wind supply chain, yet under EU state aid restrictions it was previously unable to insist on UK content in its award of contracts for difference. The Scottish Government also felt unable to specify the levels of Scottish content during the awarding of seabed leases. With the new arrangements in place between the UK and the EU, it may be possible that public bodies in the UK could have more freedom to require benefits to local supply chains.

In relation to state aid, the Committee also called for the Scottish and UK Government to ensure that any future subsidy regime gives Scottish firms the basis to compete with low wage economies, and to clarify how the UK Internal Market will operate in terms of competition.

The Committee also called for changes to the Contracts for Difference regime (which rewards lowest cost production largely irrespective of origin) and to the Crown Estates to reconsider its position that securing work for the Scottish supply chain cannot be a consideration when awarding licences.

In May 2021 the UK Government set out amendments to the Contracts for Difference (CfD) process to strengthen the Supply Chain Plan for proposed developments; including:

Carrying out an assessment of a developers supply chain commitments earlier in the process

Implementing new legislative powers to assess and either pass or refuse a Supply Chain Implementation Statement

Introducing a new operating condition with the potential consequence of contract termination if a Supply Chain Implementation Statement certificate is not provided.

Offshore wind supply chain

On 28 October 2020 the Scottish Government published an offshore wind policy statement, setting out the Scottish Government aims for the offshore wind sector. This policy statement suggests that the Contacts for Difference process has led to price pressures which have hampered the ability of the Scottish supply chain to compete.

The policy statement identifies floating wind technology as a key emerging opportunity for the Scottish supply chain. Crown Estate Scotland's report Macroeconomic benefits of floating offshore wind in the UK suggests that this could support 17,000 jobs across the UK and £33.6bn GVA, with Scottish waters offering significant opportunities for deployment due to the area which is greater than 60m in depth.

Just Transition

The Just Transition Commission was established by the Scottish Government in 2019 with a remit to provide “practical, affordable, actionable recommendations to Scottish Ministers” in relation to the transition to a net zero economy.

The Commission published its final report on 23 March 2021 setting out 24 recommendations, grouped into four key messages. These key messages are 1:

Pursue an orderly, managed transition to net-zero that creates benefits and opportunities for people across Scotland

Equip people with the skills and education they need to benefit from our transition to net-zero

Empower and invigorate our communities and strengthen local economies

Share the benefits of climate action widely; ensure costs are distributed on the basis of ability to pay.

Key recommendations include that all public funding for climate action should be conditional on Fair Work terms, that the Scottish Government should develop detailed roadmaps in order to provide the public and business with certainty about the transition, that workers in carbon intensive industries will be supported in accessing skills and education to equip them for the transition. The report also recommends that:

We must move beyond GDP as the main measure of national progress. For a just transition to be at the heart of Scotland’s response to climate change, Scottish Government must champion frameworks that prioritise wellbeing.

On 16 December 2020 the Scottish Government and Skills Development Scotland published 'Climate Emergency Skills Action Plan 2020-2025' 2. This plan aims to ensure that Scotland develops the workforce necessary to deliver the pledge to reach net zero by 2045, while at the same time ensuring that these upskilling opportunities are open to all so that no one is left behind. The First Minister announced a Green Jobs Workforce Academy in August 2021, which will create 152 new green jobs (of which 135 will be based in Scotland).

The Scottish Government published an initial response to the Just Transition Commission's final report on 7 September. Four overarching themes are set out 3:

Planning for a managed transition

Equipping people with the knowledge and skills they need, while putting in place safety nets to ensure no-one is left behind

Involving those who will be impacted: co-design and collaboration

Spreading the benefits of the transition widely, while making sure the costs do not burden those least able to pay.

The Programme for Government (PfG) was also published on Tuesday 7 September, and as well as agreeing to establish "a just transition plan for every sector and region, and promoting a net‑zero economy which provides opportunities for all" it undertakes to 4:

[…] confirm a refreshed remit for the next Just Transition Commission. This will focus on supporting the delivery of our shared ambition, and in particular, the co-design of Just Transition Plans for specific industries.

The first Just Transition Plan, for the energy sector, is expected to be published alongside the new Energy Strategy this year.

Demand Reduction

The most recent Scottish House Conditions Survey shows that 1:

In 2019 an estimated 24.6% (around 613,000 households) of all households were in fuel poverty. This is similar to the 2018 fuel poverty rate of 25.0% (around 619,000 households) but lower than that recorded in the survey between 2012 and 2015

12.4% (or 311,000 households, a subset of the 613,000 in fuel poverty) were living in extreme fuel poverty in 2019 which is similar to the 11.3% (279,000 households) in the previous year but a decrease from 16% (384,000 households) in 2013.

Fuel poverty is particularly high in rural areas due to a combination of demographic factors (older households), infrastructure (properties off the gas grid) and matters relating to the housing stock (more detached and hard to insulate homes). The policy areas of energy efficiency and fuel poverty are very closely linked, although not mutually exclusive.

Energy efficiency is now considered to be a National Infrastructure Priority; National Planning Framework (NPF) 3 undertakes to create a step change in the energy efficiency of homes, and states 2:

Much of our energy infrastructure, and the majority of Scotland’s energy consumers, are located in and around the cities network. The cities network will also be a focus for improving the energy efficiency of the built environment. A key challenge, but also a significant opportunity for reducing emissions, lies in retrofitting efficiency measures for the existing building stock

Given the relatively high energy costs for households in rural Scotland, there will be particular benefits from improving the energy efficiency of homes and businesses.

A new National Planning Framework (NPF4) is expected to be published in 2021.

The Energy Efficient Scotland (EES) programme is therefore the cornerstone of Scottish Government's approach, and the Route Map seeks to remove "poor energy efficiency as a driver for fuel poverty" and to reduce "greenhouse gas emissions through more energy efficient buildings and decarbonising our heat supply" 3.

The EES Route Map points to the Scottish Government's Climate Change Plan (CCP) for relevant policies and proposals. This has recently been updated in light of Scotland's net-zero 2045 target (CCPu), and has the key outcome that, by 2032 4:

Our homes and buildings are highly energy efficient, with all buildings upgraded where it is appropriate to do so, and new buildings achieving ultra-high levels of fabric efficiency.

SPICe Briefing Update to the Climate Change Plan - Key Sectors provides more detail.

The CCPu, as recommended by the Climate Change Committee, also undertakes to publish a Heat in Buildings Strategy, which has recently been consulted on5. Key proposals include:

Standards and Regulation for heat and energy efficiency, where it is within legal competence, to ensure that all buildings are energy efficient by 2035 and use zero emission heating and cooling systems by 2045. This represents an acceleration of the current aim of all buildings meeting EPC band C by 2040

Significant investment of £1.6bn in heat energy efficiency in this parliament. There is a commitment to design programmes so as not to exacerbate fuel poverty. Future delivery programmes will be designed to significantly accelerate retrofit building with new programmes to be in place from 2025. The rate of zero emissions heat installations in new and existing homes is planned to double every year to 2025, which will mean that around half of all Scotland's homes will be converted to low carbon heat in less than a decade

A review of supply chain support to build a more detailed understanding of the potential for growth. Other actions include setting out a supply chain strategy and new skills requirements for installers, designers and retrofit coordinators.

Significantly, a new National Public Energy Agency will be created, the recently published Programme for Government states 6: