Scottish Criminal Justice System: The Prison Service

This subject profile outlines the operation of prisons and young offender institutions in Scotland.

Introduction

This subject profile is one of six covering various aspects of the Scottish criminal justice system. It outlines the operation of prisons and young offender institutions. The latter are used for prisoners aged 16 or over but under 21.

Children aged 16 and 17 may also be held in secure care accommodation for children rather than young offender institutions.

The other five briefings in this series deal with:

legal and administrative arrangements

the police

the public prosecution system

the criminal courts

children.

Scottish Prison Service

The Scottish Prison Service is an executive agency of the Scottish Government with responsibility for Scotland's prisons and young offender institutions. Its responsibilities extend to both publicly and privately managed prisons. The latter are operated under contract by private companies but are still part of the Scottish Prison Service estate. All prisoners, regardless of their location, are managed in accordance with prison rules and directions.1

The Scottish Prison Service operates in accordance with a framework document which is approved by the Scottish Ministers.2 It provides guidance on topics including:

the role of the Scottish Ministers

the role of the Scottish Prison Service Chief Executive

accountability to the Scottish Parliament.

In an introduction to the framework document, the then Scottish Prison Service Chief Executive stated that:

the aim of the Scottish Prison Service is to contribute to a safer Scotland by contributing to reducing re-offending through the care, rehabilitation and re-integration of those citizens committed into custody. I am personally accountable to the Scottish Parliament for the efficient and effective operation and financial management of the Scottish Prison Service and for performance against key performance indicators.

Prisoners

Types of prisoner

Prisons and young offender institutions hold both remand and sentenced prisoners:

remand – held in custody awaiting trial or following conviction awaiting sentence

sentenced – serving a custodial sentence.

Young offender institutions hold those aged 16 or over but under 21.

As well as being imprisoned in young offender institutions, children aged 16 and 17 may be held in secure care accommodation for children. This type of secure accommodation also holds children under 16. It is not part of the Scottish Prison Service estate. Information on secure care accommodation is provided on the Scottish Government's website.1

Prisoners serving sentences (in both prisons and young offender institutions) are also categorised as:

short-term prisoners – determinate custodial sentences of less than four years

long-term prisoners – determinate custodial sentences of four or more years

life sentence prisoners – indeterminate custodial sentences (life sentences and orders for lifelong restriction).

The categorisation by length of sentence affects release arrangements.

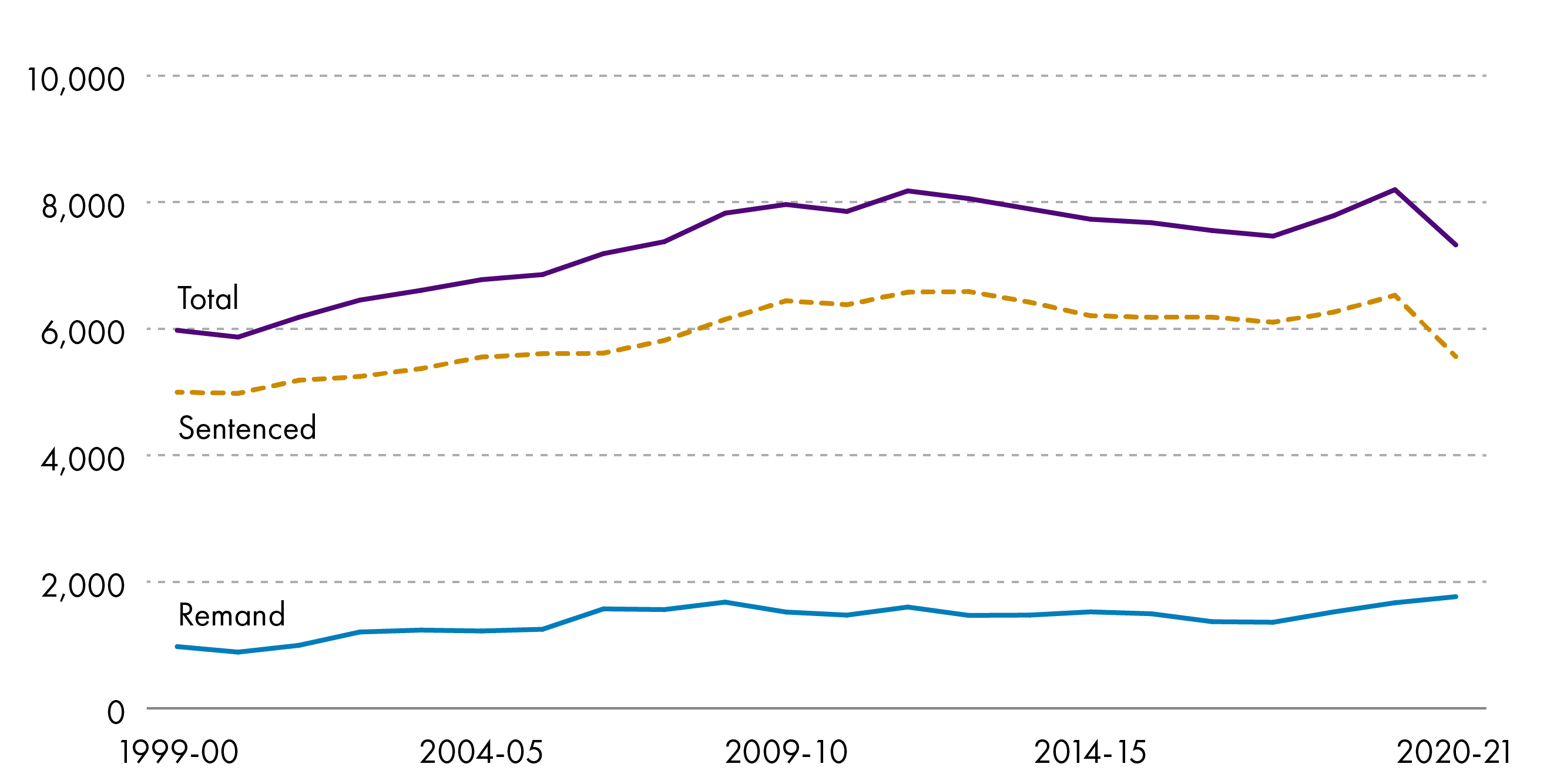

Prison population: total, sentenced and remand

In 1999-00, the total average daily prison population (including those held in young offender institutions) was just under 6,000. By 2011-12 it had risen to almost 8,200.

There then followed a period of gradual decline, to less than 7,500 by 2017-18. However, this fall was reversed during the following two years, so that in 2019-20 the average daily population was again almost 8,200.

In 2020-21, the figure fell significantly to a little over 7,300. This was linked to temporary measures taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic:

additional powers to release prisoners before the end of their sentence – directly aimed at supporting the safe management of prisons by reducing the prison population during the pandemic

restrictions on the carrying out of criminal court business – aimed at the safe running of the courts during the pandemic but limiting the level of business concluded and thus numbers of custodial sentences imposed.

The Scottish Prison Service's annual report for 2019-20 (p 41) noted that:1

The prison population remained over 8,000 until March 2020 when the impact of COVID-19 resulted in fewer people being sent to custody due to the suspension of court business. Upon the resumption of court business, it is anticipated that this declining trend will reverse and the numbers of people in custody will increase significantly, bringing with it the added complication of delivering service whilst adhering to physical distancing requirements.

The following chart shows how the average daily prison population has changed since devolution. As well as plotting the total population, it breaks this down into sentenced and remand prisoners.

The reduction in 2020-21 was in the sentenced population only – falling by close to 1,000.

The remand population did not fall in 2020-21, instead rising to a high point of over 1,700 (it was under 1,000 in 1999-00). This represented close to a quarter of the total prison population in 2020-21. Although delays in concluding cases during the pandemic meant fewer people receiving custodial sentences, such delays also made it more difficult to keep periods of remand within normal statutory time limits. This is reflected in the temporary extension of those limits by the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020 (Part 4 of Schedule 4).

Whilst COVID-19 has affected recent levels of remand, concerns about the size of the remand population are not new. For example, a 2018 Scottish Parliament Justice Committee report on the use of remand noted that (para 144):2

A key issue throughout the Committee's inquiry was whether any steps could be taken to reduce what many witnesses perceived to be an inappropriately high use of remand.

The inquiry included consideration of what might be done to encourage more use of alternatives to remand (e.g. by increasing the level of support and supervision available for those released on bail). One of the issues highlighted in this context was the use of electronic monitoring as a possible condition of bail. The Management of Offenders (Scotland) Act 2019 was amended last year to allow for this possibility. Relevant provisions are not in force at the time of writing. However, on 10 June 2021 (during a parliamentary debate on justice issues) the Cabinet Secretary for Justice indicated that it should be possible to commence them after the summer.3

The figures discussed above include both male and female prisoners - those under 21 as well as those aged 21 and over. Later sections of this briefing focus on female prisoners and prisoners under 21. However, most of the prison population consists of men aged 21 and over (more than 90% in 2020-21).

Although a minority, there has been a growth in the proportion of prisoners aged 50 or more (including those aged over 65). This brings with it a range of additional challenges for the Scottish Prison Service (e.g. in providing appropriate healthcare and accessible facilities). The issue is considered in a report by HM Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland on the experience of older prisoners.4

Further information on how the prison population has changed since devolution, including consideration of some of the factors driving those changes, is provided in the 2019 SPICe blog Twenty Years of Imprisonment.5 Also see Scottish Government prison population statistics.6

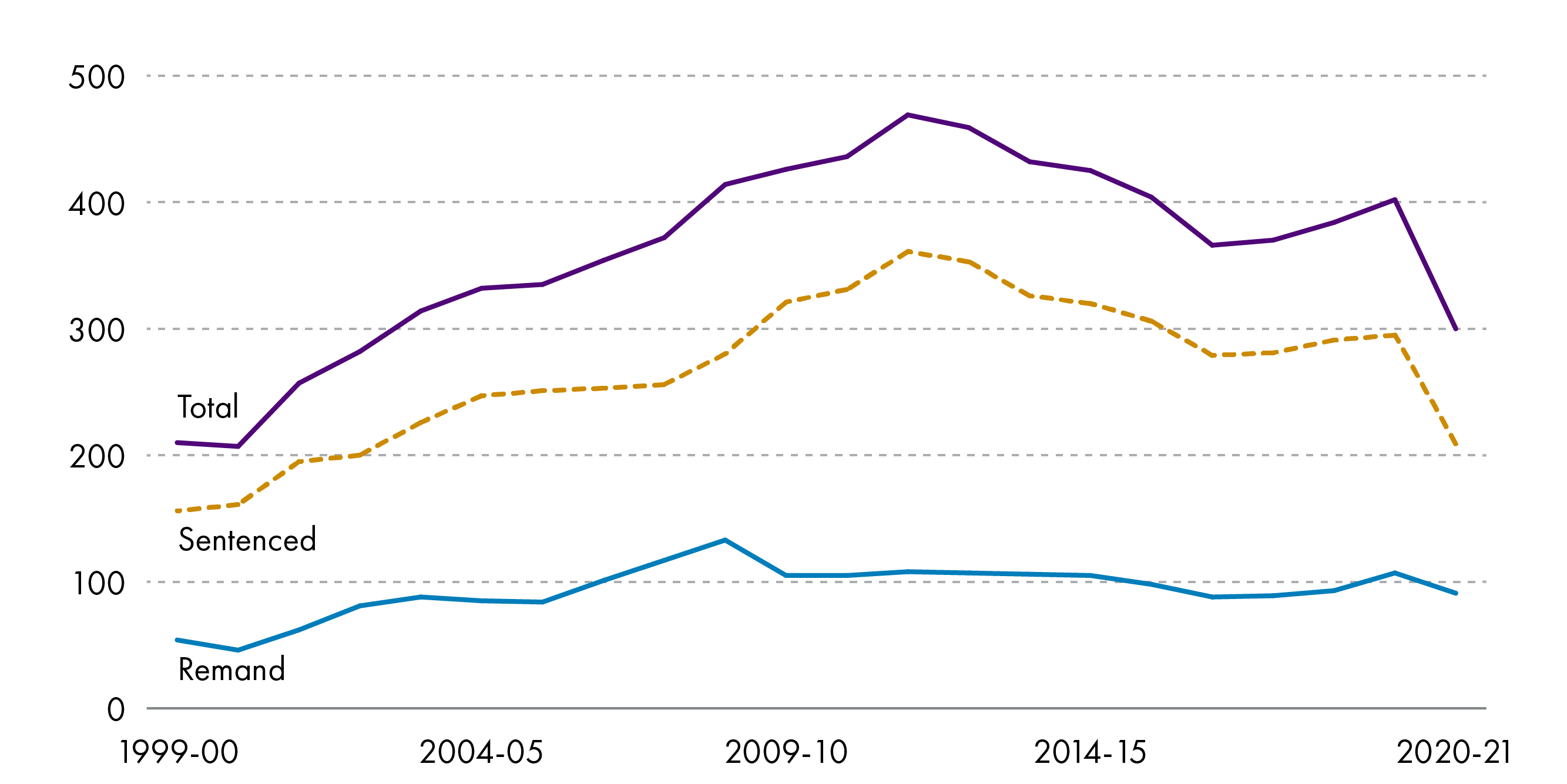

Prison population: female

The next chart shows how the average number of female prisoners has changed since devolution.

Although forming a relatively small proportion of the total prison population (4% in 2020-21), specific concerns have been highlighted in relation to the use of imprisonment for women. Reasons for this include:

analysis of the circumstances which frequently form part of the history of women in prison (e.g. victims of abuse and/or poor mental health) and of the impact of imprisonment on female prisoners and their families

the scale of changes in the female prison population.

In relation to the second point, the total figure for female prisoners rose by 123% between 1999-00 and a high point in 2011-12. Despite reductions since then, it was still 43% higher in 2020-21.

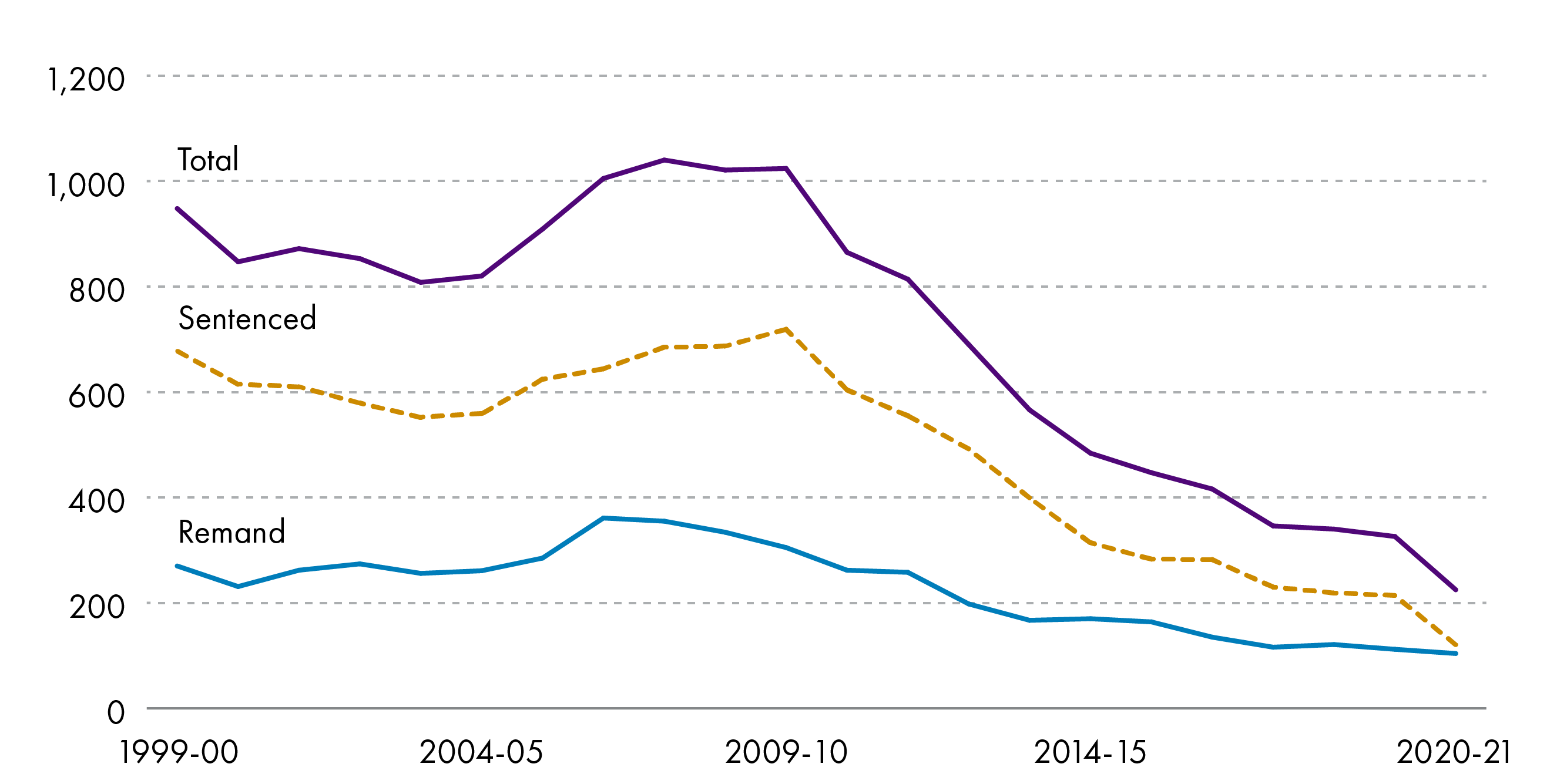

Prison population: under 21

The final prison population chart shows how the number of prisoners under 21 (male plus female) has changed since devolution.

Unlike the categories of prisoner considered earlier, a sustained reduction in numbers during the second half of the period meant that significantly fewer young offenders were held in custody in 2020-21. A 76% fall in the total figure compared to 1999-00.

Prison estate

Current prison estate

The prison estate consists of 15 prisons (including young offender institutions):

publicly managed - Barlinnie, Castle Huntly, Cornton Vale, Dumfries, Edinburgh, Glenochil, Grampian, Greenock, Inverness, Low Moss, Perth, Polmont and Shotts

managed by private sector operators - Addiewell and Kilmarnock.

The Scottish Prison Service website provides information on individual prisons (including a map of prison locations).1

This prison estate has to cater for a diverse prison population. Separate provision is made for prisoners based on a range of factors. These include gender, age (under 21 or 21 and over), and whether a prisoner is serving a custodial sentence or is being held on remand.

Other factors, such as the nature of the offences involved (e.g. sex offending or organised crime), may also require segregation of prisoners - for their own safety or that of other prisoners. The Scottish Prison Service has highlighted the risks posed by increasing numbers of people in prison with links to serious organised crime groups.2

Some prisons generally hold particular categories of prisoner. For example:

Polmont holds most of the under 21 prison population

Cornton Vale is a dedicated women's prison, although female prisoners are also held as separate populations in other prisons

Castle Huntly is an open prison accommodating low supervision adult male offenders.

Prisons also differ greatly in terms of their size. In 2019-20, the average daily population ranged from just under 100 in Cornton Vale to just over 1,400 in Barlinnie.2

Much of the current prison estate has been built within the past 25 years or so. However, considerably older buildings are still in use (e.g. parts of Barlinnie date back to the 1800s).

Ongoing challenges for the Scottish Prison Service include:

the need for further modernisation of the prison estate - to ensure that the whole estate (including buildings and the integration of technology) helps support an efficient, effective and humane prison regime

dealing with overcrowding in parts of the prison estate.

In her annual report for 2019-20, the Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland noted (p 21):4

In the previous 12 years Scotland's prisons had seen an investment in infrastructure and innovation that transformed the prison landscape and gave Scotland credibility for enlightened penology, architecture and design on an international stage. In the recent years, however, Scotland has been in danger of undermining that reputation through overcrowding and continued reliance on antiquated Victorian prisons that are not fit-for-purpose.

She welcomed recent investment in new facilities at Low Moss and Grampian, whilst highlighting an urgent need to make progress in replacements for Barlinnie, Greenock and Inverness.

Development of the prison estate

In January 2021, the Scottish Government set out its spending proposals for 2021-22 in its annual budget document.1 It included information on plans for the prison estate, stating that key priorities for investment are the new female prison estate and progressing work to replace Barlinnie and Inverness prisons.

Female prison estate

In 2011, the Scottish Government established a Commission on Women Offenders tasked with considering evidence on how to improve outcomes for women in the criminal justice system.2 In relation to the female prison estate, the Commission's 2012 report recommended:

the replacement of Cornton Vale with a smaller specialist facility for long-term and high-risk prisoners

the use of local prisons for most remand and short-term sentence prisoners.

The Commission's recommendations helped shape the Scottish Government's plans which in time settled on the creation of:

a new 80-place national facility, including an admissions assessment centre for an additional 24 women, on the existing Cornton Vale site

five smaller community-based custodial units for other female prisoners (allowing them to be held closer to their families).

The national facility is intended for women with higher security requirements or more complex needs. Part of the existing Cornton Vale prison population was moved to other prisons to allow work on the new facility to proceed.

The community-based custodial units are intended for all other female prisoners, allowing them to be held closer to families and friends.

In communications with the author (May/June 2021), the Scottish Prison Service provided the following update on progress in taking forward the plans:

Cornton Vale - the contract to build the new facility was awarded in December 2019, with work commencing on site in February 2020 (suspended due to COVID-19 for three months). The main phase of construction is programmed to be completed by Spring 2022, with a second phase which includes the demolition of the remainder of the existing prison following on through to Spring 2023. It is anticipated that the new facility will be brought into operation within six to eight weeks of the main construction phase being completed in Spring 2022.

Glasgow community-based custodial unit (capacity 24) - the contract to build the facility was agreed in January 2020. The start of construction was, due to COVID-19, delayed until October 2020. Building work is programmed to be completed by early 2022, with the potential for it being operational in Spring 2022.

Dundee community-based custodial unit (capacity 16) - the contract to build the facility was agreed in January 2020. A combination of COVID-19 and planning issues delayed the start of work on site until November 2020. Construction is programmed to be completed in late 2021, with the potential for it being operational around April 2022.

Further community-based custodial units - discussions have not yet taken place to identify specific locations for the three remaining units. It is intended that there will be an assessment of the first two (Glasgow and Dundee) before progressing with the others.

Male prison estate

The Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland has called for progress in replacing outdated facilities at Barlinnie, Greenock and Inverness. In communication with the author (May 2021), the Scottish Prison Service provided the following update on plans for their replacement:

Inverness - a new site for a 200-place replacement (to be called 'Highland') was acquired in 2018. Construction work is currently programmed to be completed in Autumn 2023, with the facility operational by early 2024.

Barlinnie - currently aiming to secure a contractor this year to develop the design of a replacement (to be called 'Glasgow'), allowing work on site to start during 2023 with completion in 2026. The new facility could be operational by early 2027.

Greenock - a suitable site for a replacement has been purchased. However, given current financial and operational pressures, as well as other prison investment priorities, it is unlikely that work at the site will start before 2025-26.

Prison life

The Scottish Prison Service is tasked with holding prisoners in a safe and secure environment. It also seeks to provide services which support the rehabilitation of prisoners, including their successful reintegration into society upon release.

This section of the briefing contains information on two areas which are important in rehabilitation and reintegration, as well as in providing a humane environment for those in custody:

Purposeful activity

The term purposeful activity is generally used to cover a range of constructive activities within prisons and young offender institutions, including:

work

education and vocational training

counselling and other rehabilitative programmes.

In providing these activities, the Scottish Prison Service works with various partner organisations.

In 2013, a report of the Scottish Parliament's Justice Committee emphasised the importance of purposeful activity in rehabilitating offenders.1 A joint response by the Scottish Government and Scottish Prison Service agreed (p 1):2

The Scottish Government and the Scottish Prison Service welcomes and shares the Committee's views that purposeful activity is crucial to the rehabilitation and the reintegration of prisoners back into society.

The provision of purposeful activity is one of the aspects of the prison regime specifically addressed in the work of HM Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland. Reflecting on this area, following inspections carried out between April 2019 to January 2020, the Chief Inspector of Prisons reported:3

satisfactory performance at Dumfries

generally acceptable performance (some improvements required) at Barlinnie, Edinburgh and Glenochil.

Areas of concern highlighted by the Chief Inspector included:

the negative impact of overcrowding and staff shortages

gaps in provision for particular categories of prisoner (e.g. those held on remand)

prisoners not having access to relevant offending behaviour programmes (e.g. affecting progression through the sentence and chances of release on parole).

The above inspections were carried out before the impact of COVID-19 was felt. Commenting on the impact, the Scottish Prison Service's annual report for 2019-20, published in December 2020, noted that (p 19):4

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and in order to ensure compliance with physical distancing guidelines, purposeful activity was suspended in March 2020, with the exception of those services required to keep the establishments running, such as catering, laundry and other critical support services.

In communication with the author (June 2021), the Scottish Prison Service advised that purposeful activity had not yet recommenced across the prison estate. However, planning for the next phase of its pandemic response included the restoration of more services. It emphasised that a cautious approach would be taken, with measures aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 remaining in place.

Contact with family and friends

Where appropriate, maintaining contact between prisoners and their families and friends can play an important role in:

providing a humane environment for prisoners

supporting the successful reintegration of prisoners back into the community upon release.

It can also help lessen the negative impact which separation may have on those left to cope with the imprisonment of a family member (e.g. where the parent of a child is imprisoned).

Sources of advice on visiting prisoners include:

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person visits by family and friends were subject to restrictions, including periods where visits were suspended. The pandemic did, however, help encourage the roll-out of other options for maintaining contact. The Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland noted in her 2019-20 annual report that she was (p 35):3

delighted to see the introduction of in-cell telephony and virtual visits coming to fruition, which provides much needed alternative family contact capability. This is a step forward in Scotland's enlightened approach to penology and will be welcome even after the current crisis, as a very useful supplement to face-to-face visits, particularly for prisoners held far from their families.

Release of prisoners

Early release

The rules on early release from a custodial sentence are mainly set out in the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993. They differ depending upon whether a prisoner is a:

short-term prisoner – serving a determinate custodial sentence of less than four years

long-term prisoner – serving a determinate custodial sentence of four or more years

life sentence prisoner – serving an indeterminate custodial sentence (life sentence or order for lifelong restriction).

They include the following:

Short-term prisoners must be released after serving one-half of the sentence. For most prisoners, this release is not subject to licence conditions and thus not subject to supervision by criminal justice social work. However, sex offenders receiving sentences of between six months and four years are released on licence.

Long-term prisoners serving sentences imposed before 1 February 2016 may be released after having served at least one-half of the sentence. If not already released, such prisoners must be released after serving two-thirds of the sentence. Any decision to release before the two-thirds point is taken by the Parole Board, following an assessment of whether a prisoner is likely to present a risk to the public if released. Long-term prisoners are, irrespective of the proportion of sentence served in custody, released on licence under conditions set by the Parole Board and subject to supervision by criminal justice social work. The licence, unless previously revoked, continues until the end of the whole sentence.

Long-term prisoners serving sentences imposed on or after 1 February 2016 may also be released after having served one-half of the sentence but automatic early release at the two-thirds point of the sentence no longer applies. Changes to the rules, limiting the scope of automatic early release, were made by the Prisoners (Control of Release) (Scotland) Act 2015. However, the rules include provisions seeking to ensure that a period of post-release supervision is preserved for long-term prisoners. For some, this is achieved by retaining automatic early release at the point when the prisoner has six months of the sentence left to serve. Any decision to release before this point is taken by the Parole Board on the same basis as for long-term prisoners sentenced before 1 February 2016. The provisions relating to licence conditions and supervision are also the same as before.

Life sentence prisoners have a punishment part set by the court when imposing the sentence. This is the period that the court considers appropriate to satisfy the requirements of retribution and deterrence, but ignoring any period of confinement necessary for the protection of the public. The prisoner serves the whole of the punishment part in custody. Such a prisoner may be released after this point if the Parole Board considers that continued incarceration is not required for the protection of the public. The possibility of release is considered again periodically where the Parole Board does not initially order the release of the prisoner. Prisoners are released on licence, continuing until the person's death, under the supervision of criminal justice social work.

Breach of licence conditions can lead to a released prisoner being recalled to custody.

In addition, the Scottish Prison Service has the power to release prisoners, before the point dictated by the above rules, on what is known as home detention curfew. During this period the prisoner wears an electronic tag and is subject to conditions including a curfew.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Release of Prisoners (Coronavirus) (Scotland) Regulations 2020 set out time-limited measures (applying to a period in 2020) providing for the release of some short-term prisoners before the half-way point of their sentence. Release was not subject to the restrictions applying to release on home detention curfew. The measures were aimed at supporting the safe management of prisons by reducing the prison population during the pandemic.

Home detention curfew

Since 2006, the Scottish Prison Service has had the power to release prisoners on home detention curfew. This allows prisoners to serve an additional part of their sentence in the community (e.g. prior to the standard early release of short-term prisoners at the half-way point of their sentence).

Relevant provisions are set out in the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993 and are exercised by the Scottish Prison Service on behalf of the Scottish Ministers.

The provisions allow prisoners to spend up to a quarter of their sentence on licence in the community (with a maximum of six months) while wearing an electronic tag. Release conditions include a curfew, monitored using the tag, under which a prisoner must remain at a particular place for a set period each day. Breach of licence conditions can result in recall to custody.

Release on home detention curfew is mainly used in relation to short-term prisoners but can also be used for some long-term prisoners. Not all prisoners within these categories are eligible for release on this basis (e.g. sex offenders). In relation to those who are eligible, release is not automatic. Prior to any release, the Scottish Prison Service carries out an assessment including consideration of public protection, prevention of re-offending and securing successful re-integration of the prisoner in the community.

Rules and procedures, relating to the release and enforcement of conditions, were tightened in light of concerns arising from the 2018 conviction for murder of a prisoner who had been released on home detention curfew and was in breach of his release conditions when he committed the crime. Changes included some legislative changes made by the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Act 2019.

Further information is set out on the websites of the:

Following the tightening of rules and procedures, there was a significant fall in the number of prisoners released on home detention curfew. Scottish Government figures for the ten-year period 2010-11 to 2019-20 indicate that:3

during the first eight years, the number of prisoners released on home detention curfew ranged between 1,399 (in 2016-17) and 1,935 (in 2011-12)

in 2018-19, the figure was 878

in 2019-20, it was 196.

Transition to the community

The successful reintegration of prisoners back into the community may depend upon a range of measures aimed at tackling existing problems and avoiding the creation of new ones. These include:

programmes to address offending behaviour and addiction issues

support for prisoners in maintaining positive relationships with family and friends in the community

support for prisoners in obtaining stable accommodation, social security benefits and work upon release.

Some of this may be spread across a person's time in prison (e.g. see earlier discussion on purposeful activity in prison and contact with family and friends).

Other aspects may be focused during a period before and following release. This is sometimes referred to as throughcare. In addition to prison personnel, it may involve:

central and local government services - including ones with a criminal justice focus (e.g. criminal justice social work) and more general ones (e.g. dealing with health and social security)

third sector providers of services (e.g. the Wise Group - a social enterprise providing mentoring and other services)1

private sector organisations (e.g. the Scottish Prison Service seeks to develop partnerships with businesses which are looking to offer employment opportunities to people with convictions).

The importance of both criminal justice bodies and other organisations working effectively in combination was highlighted in a 2015 Scottish Government report of a Ministerial Group on Offender Reintegration.2 It noted (p 2):

The work of this group has found that re-offending is a complex social issue and there are well established links between persistent offending, poverty, homelessness, addiction and mental illness. When transitioning from custody to the community, gaps in access to vital support services and basic needs can hamper attempts to desist from offending. Not all structural factors and social factors are amenable to change by the criminal justice system, but it is important to note that many different bodies and agencies must work effectively and collaboratively to support those in our criminal justice system who may face challenges in multiple areas of their lives.

It is not only those serving custodial sentences who can face problems upon release from prison. People held on remand, for even relatively short periods, may be affected by similar issues (e.g. loss of housing, work or welfare benefits). A 2018 Scottish Parliament Justice Committee report, on the use of remand, highlighted the potential benefits of throughcare support for remand prisoners.3

As part of its role in preparing prisoners for release, the Scottish Prison Service created a specific role for some of its staff as Throughcare Support Officers. However, in her 2019-20 annual report the Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland noted that their role had been suspended to "help address staff resourcing issues elsewhere in Scotland's prisons" (p 26).4 She went on to praise the role they had performed and called for restoration of that role at the earliest opportunity.

Inspection and monitoring of prisons

HM Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland,1 headed by the Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland, has responsibility for the inspection and monitoring of Scotland's prisons and young offender institutions. Other responsibilities include the inspection of court custody units and prisoners under escort.

The inspection of prisons and young offender institutions involves a programme of regular inspection visits as well as unannounced visits. The work is carried out by Inspectorate staff together with subject experts from other organisations (e.g. the Care Inspectorate, Education Scotland,Healthcare Improvement Scotland and the Scottish Human Rights Commission).

Monitoring is a regular weekly activity carried out for each prison and young offender institution by independent prison monitors - trained volunteers from the local community. During visits, monitors check on the treatment and conditions of prisoners and can investigate issues raised by individual prisoners.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, planned inspections and regular monitoring visits were temporarily suspended in March 2020. Following risk assessment, an approach to inspection during the pandemic involving remote monitoring (using information provided by the Scottish Prison Service) along with shorter visits by inspection teams was put in place. The approach of the Inspectorate to its work continued to develop in response to the state of the pandemic. For example, greater use of on-site monitoring was reintroduced in February 2021.2

Prison complaints

Prisons and young offender institutions have internal complaint procedures which prisoners should use in the first instance.

Where a prisoner is not satisfied with the outcome of internal procedures, a complaint can be raised with the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO). It's website includes the following information for prisoners: