Scottish Budget 2022-23

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2022-23. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our budget spreadsheets. Infographics produced by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, and Fraser Murray.

Executive Summary

Initial chamber debate on this year’s budget focussed on whether the Budget is increasing or decreasing on the year before. This centred on the treatment of COVID-19 funding. In the recent UK government Autumn Budget and Spending Review, the UK government stripped out COVID-19 allocations from the baseline year, meaning that 2022-23 showed as a very healthy 7.7% increase. The UK government argued this was a fair like-for-like comparison as it intended to wind-down COVID-19 financial interventions next year.

The Scottish Government’s presentation went with a different approach, including the COVID-19 allocations for 2021-22 in the baseline. This has the effect of showing a reduced overall spending envelope in real terms in 2022-23 relative to 2021-22. The Scottish Government argues that as the pandemic is still with us and requiring financial support, it is better to include COVID-19 funding in the baseline.

This briefing, and the accompanying SPICe spreadsheets and infographics present the numbers as outlined in the Budget documents, which include COVID-19 funding in 2021-22.

The Cabinet Secretary uses some of the flexibilities afforded by the Fiscal Framework with the UK Government to supplement the budget, via the drawing down of £179 million from the Scotland Reserve, borrowing £15 million in Resource and £450 million in Capital.

Additionally, the plans include some assumptions around significant anticipated Budget income from UK government transfers (£92 million) and “other income” (£620 million). Commenting on these assumptions, the SFC expressed some scepticism, but overall assessed them as ‘reasonable’.

The net impact of this means that, according to the presentation in the Budget, the Scottish Government discretionary spending power for next year will be £45,588 million (Resource and Capital), which equates to a real terms decrease of 2.3% on the current year (2021-22).

Health and Social care receives by far the largest slice of the spending cake, at just over £18 billion in 2022-23, representing 44% of the total Resource, or day-to-day, budget.

As with the overall budget, and the debate between the Scottish and UK Governments, the total headline figures for local government were, again, subject to debate and differing presentations - this time between the Scottish Government and COSLA. Looking at the total local government settlement in the Budget, this represents a £33 million increase over the year, translating as a cash increase of 0.3%, or a real terms reduction of 2.4% (or -£268 million). However, once revenue funding which is transferred from other portfolios to local government is included, the cash increase is £854 million over the year (7.3%) or a real terms increase of £539 million (4.5%). This is the Scottish Government's preferred presentation. COSLA on the other hand presented the headline figure as a £100 million cut. As in recent years, the local government budget will again be subject of much parliamentary interest and debate, and a dedicated SPICe briefing will follow.

Perhaps the biggest story in this year’s Budget is that, for the first time since income tax powers were devolved in 2017-18, the SFC forecasts made at the time of the budget are lower than the equivalent Block Grant Adjustment (BGA). The SFC expects Scottish income tax revenues to grow more slowly than in rUK, with significant implications for the size of the Scottish spending envelope.

For 2022-23, the SFC predicts that the Scottish Budget will be worse off than it would be without income tax powers to the tune of £190 million. This is despite people living in Scotland paying around £500 million more in income tax overall than income tax payers south of the border. For more detail on income tax in Scotland, please see our detailed briefing from earlier this year.

Sadly for Scotland’s public finances, the SFC expects this BGA income tax gap to grow over the forecast period, reaching £417 million by 2026-27.

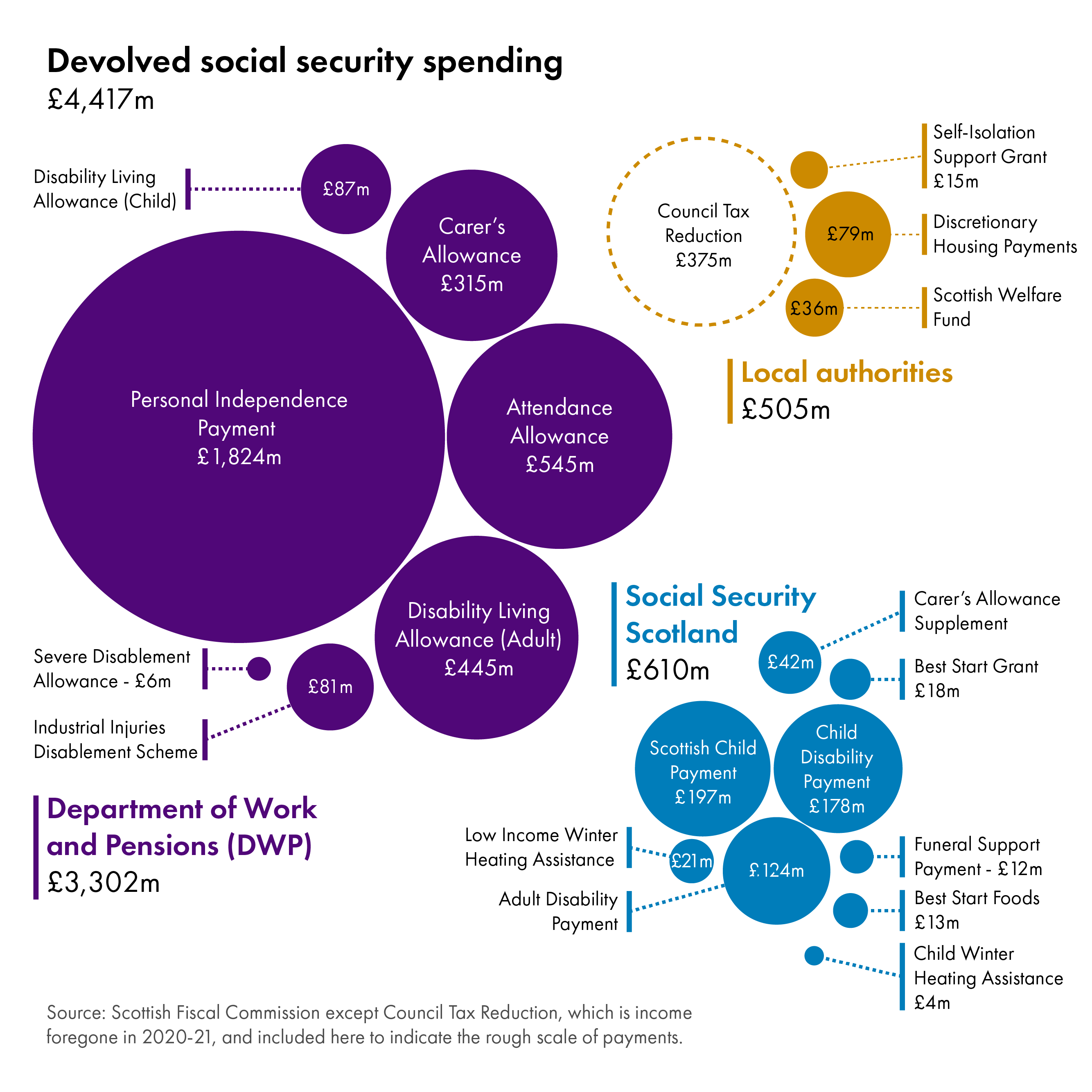

In 2022-23, the BGA added to the Scottish budget for social security is £3,587 million, but the forecast spend on social security is £4,065 million, a gap of nearly £500 million. Much of this difference is explained by the introduction by the Scottish Government of new social security payments which would not be expected to be covered by the BGA because they are unique to Scotland, such as the Scottish Child Payment.

The SFC forecasts that by 2024-25, spending on social security in Scotland will be £750 million more than the corresponding funding received from the UK Government, again partly reflecting policy decisions that are unique to Scotland.

Looking at the SFC forecasts more generally, they assume minimal COVID-19 restrictions applying in Scotland and the rest of the UK, and that the vaccination programme will continue to result in a weakened link between cases, hospitalisations and deaths, and therefore public health restrictions will remain minimal. It is highlighted by the SFC that any decision by Scottish Ministers to impose tighter public health restrictions than in England, that require assistance to businesses or individuals, could pose difficulties for the Scottish Budget.

Longer term GDP growth rates for 2025-26 have been adjusted down by the SFC, relative to the August 2021 and January 2021 forecasts. A factor in this is that household disposable income is forecast to decrease due to increased inflation, and also because of higher taxes (including the Health and Social Care Levy introduced by the UK government). The reduction in income puts pressure on the savings ratio and sees a decline in household consumption over the forecast period.

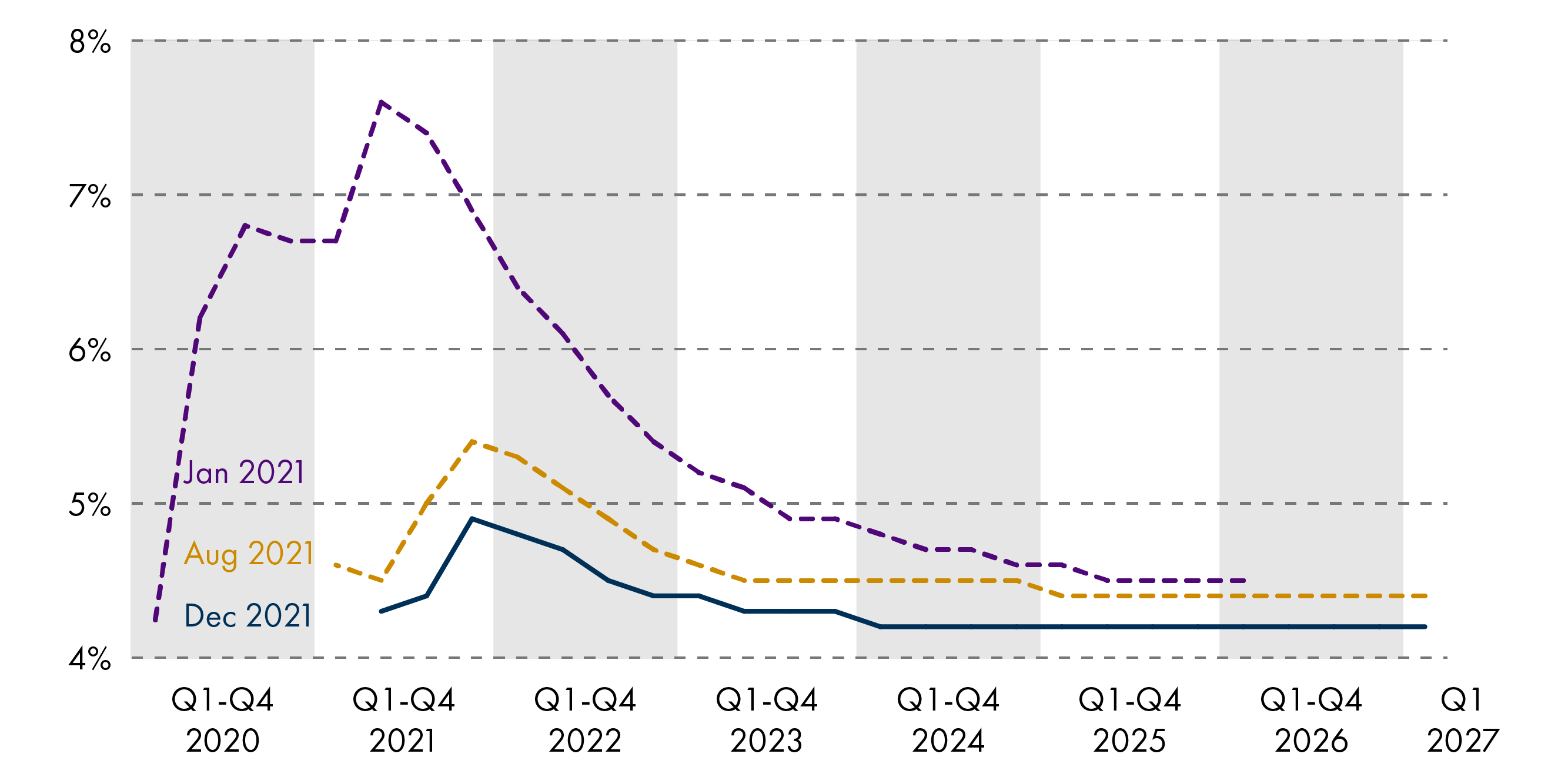

The SFC forecast sets out a more positive picture for employment in the economy compared to previous forecasts. The SFC now forecasts the unemployment rate will peak at 4.9 per cent in 2021 Q4. This is down from the peak forecasted in August 2021 of 5.4 per cent, and substantially lower than the January 2021 forecast where unemployment peaked at 7.6 per cent.

The SFC expects CPI inflation to peak at 4.4 per cent in 2022 Q2, before then gradually returning to target (2%) by the second half of 2024. However, the SFC notes that there are significant risks to the outlook for inflation and interlinked interest rates, which could impact consumer spending and house prices.

The SFC’s outlook for Scotland is much more subdued than the OBR’s outlook for the UK. In 2022, Scotland’s growth rate is 2.2 percentage points below the UK rate. The SFC suggests that despite the pace of the recovery in Scotland, there is some evidence that the Scottish economy has been lagging behind the rest of the UK. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, Scottish GDP, employment and earnings have recovered more slowly than in the UK.

There were very modest changes to income tax policy, with only minor changes to the starter and basic rate thresholds, meaning very little impact on take home pay. Scottish taxpayers earning above £27,850 continue to pay more in tax than they would pay in the rest of the UK, with those earning more than £55,000 paying more than £1,500 more per year. Overall, the different income tax policy adopted in Scotland generates around £500 million more per year in revenues than if Scotland had the same tax policy as in the rest of the UK. However, this is not reflected in the additional resources available to the Scottish Government due to the way this interacts with the block grant adjustments, as mentioned above.

Despite a reduced capital block grant from HM Treasury, the Scottish Government still expects to be able to meet the targets for increased infrastructure investment set in the National Infrastructure Mission. However, the Scottish Government warns that constrained capital budgets could impact on its ability to meet its net zero targets.

The public sector pay policy provides for inflationary increases in pay for those earning less than £25,000 and smaller increases for higher earners. It also introduces a guaranteed minimum hourly rate of £10.50 per hour, which is in excess of the current real living wage rate of £9.90 per hour.

Context for Budget 2022-23

Scottish Budget 2022-231 was published on 9 December 2021 and presents the Scottish Government's proposed spending and tax plans for next year. The publication marks the start of an intensive period of parliamentary scrutiny.

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC). As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes for the next five years, the SFC is also mandated to produce forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for devolved social security powers. The SFC's forecasts can be found in Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts2 published alongside the Scottish Budget.

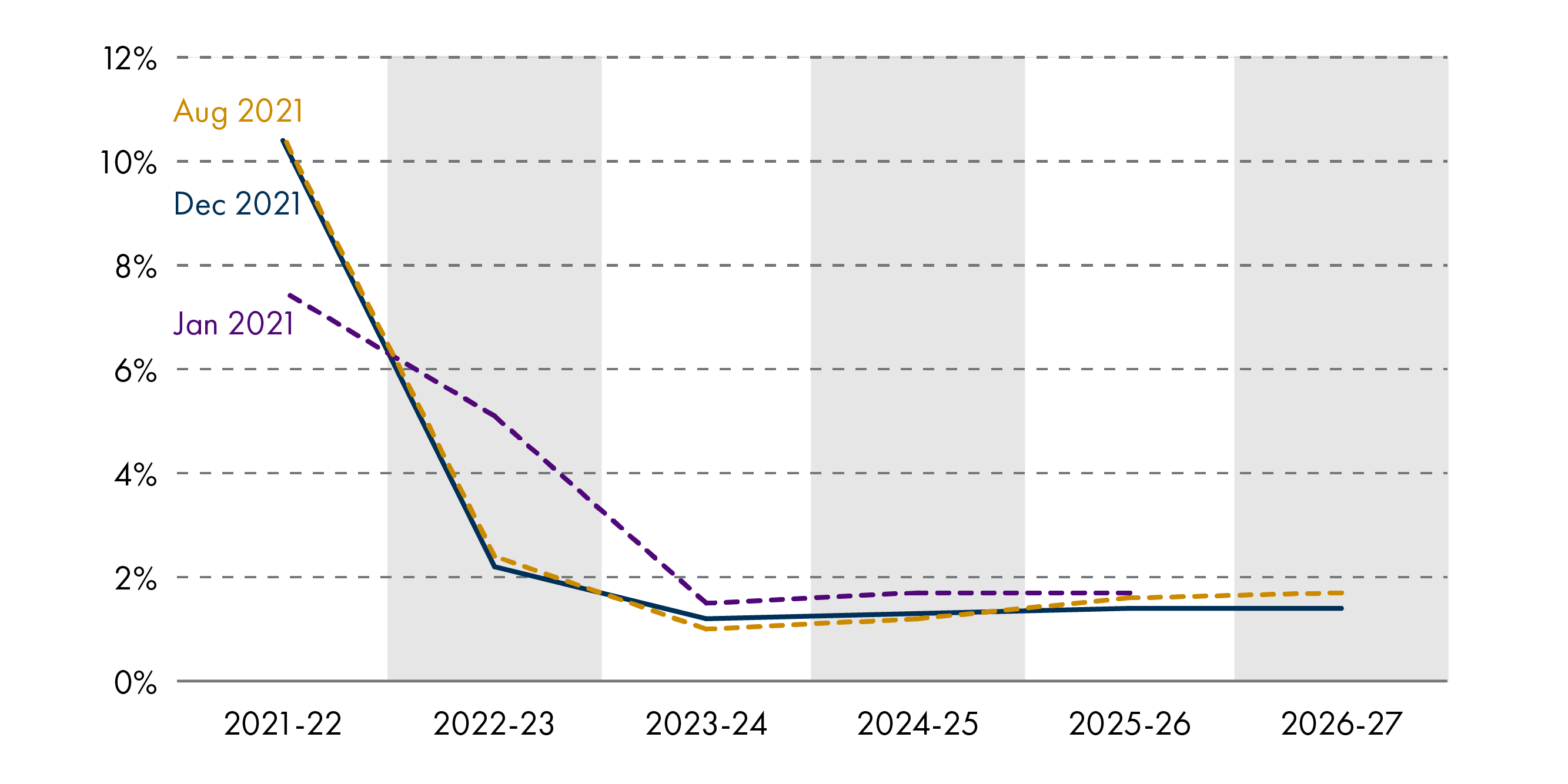

The economic outlook for 2021-22 presented by the SFC is much more optimistic than that presented when the 2021-22 Budget was introduced back in January of this year. The successful vaccine roll-out and the opening up of the economy has resulted in a more upbeat economic prospectus, with the SFC forecasting a strong bounce back in growth this year of 10.4%, and economic activity returning to pre-pandemic levels by the second quarter of 2022, earlier than previously predicted.

However, there are significant economic risks on the horizon, chief amongst them the new COVID ‘omicron’ variant, which has dominated the news agenda in the last couple of weeks. The SFC had ‘closed’ their forecast prior to the detection of this new variant, meaning that the economic outlook does not contain SFC judgements as to any possible economic impact from the new variant taking hold in the UK.

Another risk to the future economic outlook stems from inflation, which has increased in recent months, driven by high energy prices. The SFC central view is in line with that of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and Bank of England, and sees annual CPI inflation peaking at 4.4% in the second quarter of 2022. The SFC points out that if inflation remains high for a prolonged period, this will erode real disposable income and household consumption. Low income households could be disproportionately affected as they spend a higher proportion of their income on essentials like energy.

The SFC's forecasts of Scottish economic output over the forecast period are presented in the table below.

| 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy, % growth | 10.4 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

Overall spending

There has been a differing presentation by the UK and Scottish governments of the extent to which the Scottish budget is expected to change in 2022-23 compared with the current year (2021-22).

The UK government in its Autumn Budget and Spending Review1 showed the Scottish block grant to be growing by 7.7% in real terms (i.e. after adjusting for the effects of inflation). This figure is arrived at by removing COVID-19 Barnett consequentials from the 2021-22 baseline figure. The UK government argues that this is reasonable to arrive at a like-for-like comparison, as the UK government signalled in October its intention to wind-down direct pandemic related fiscal interventions.

The Scottish Government, however, takes a different view in presenting the numbers. The budget documentation includes the COVID-19 Barnett consequentials in the 2021-22 baseline, arguing that as the pandemic is still with us and requiring financial interventions., it is better to include COVID-19 funding in the baseline. The effect of presenting the numbers this way is to show the Scottish budget falling in real terms in 2022-23, relative to 2021-22.

This briefing will present the numbers as shown by the Scottish Government in the document, as this is what is actually being proposed to be spent, and to allow best read-across between SPICe analysis and the Budget.

Key discretionary choices that have been taken by the Scottish Government to boost 2022-23 spending power include using some of the flexibilities afforded by the Fiscal Framework with the UK Government2, via the drawing down of £179 million from the Scotland Reserve, borrowing £15 million in Resource and £450 million in Capital.

Additionally, the plans include some assumptions around significant anticipated Budget income from UK government transfers (£92 million) and “other income” (£620 million). Commenting on these assumptions, the SFC expresses some doubts, but overall assess them as 'reasonable':

In developing its Budget the Scottish Government has assumed that it will receive extra income of £620 million for the resource budget in 2022-23 from a number of sources, some of which are still a matter of negotiation between the Scottish and UK Governments. We have reservations about the likelihood and amount of income available from some of these sources, but, considering the possibility of resource underspends materialising in the current financial year, we consider that, on balance across all the sources together, the Scottish Government assumptions are reasonable.

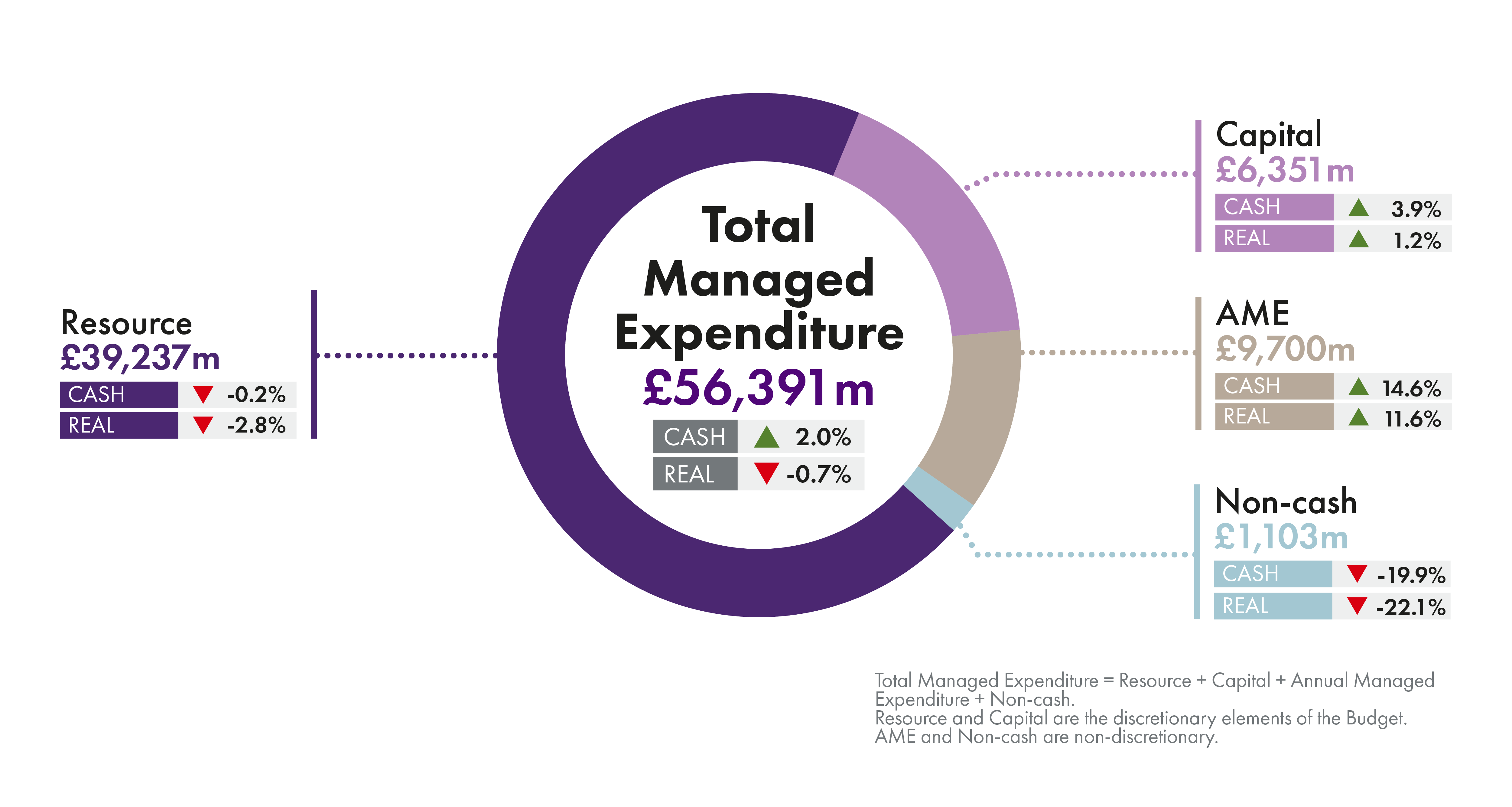

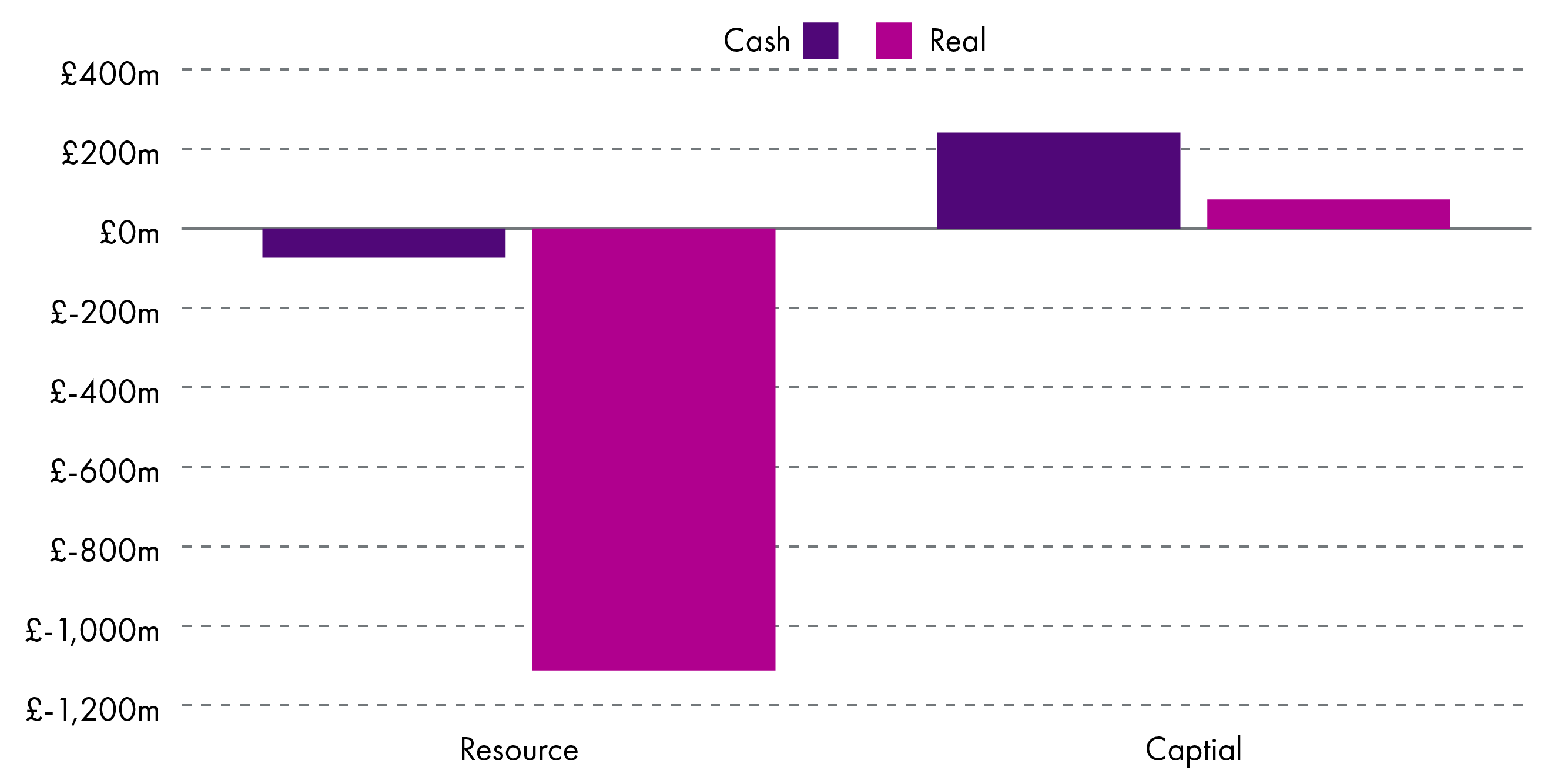

In terms of what is actually being allocated overall in the Budget (presented in the Annex of the document), the Resource budget (or day-to-day spend) is projected to fall by 0.2% in cash terms and by 2.8% in real terms.

Spend on Capital (infrastructure) is expected to increase in both cash and real terms - by 3.9% in cash terms and by 1.2% after adjusting for inflation.

The next section presents how these overall budgets have been allocated.

Budget allocations

Total allocations

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Fiscal Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2022-23 is £56,391 million. Figure 1 shows how this is allocated.

Fiscal Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and Capital (covering infrastructure expenditure) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. Non-Domestic Rates are also classed as an AME item in the budget and form part of local government spending.

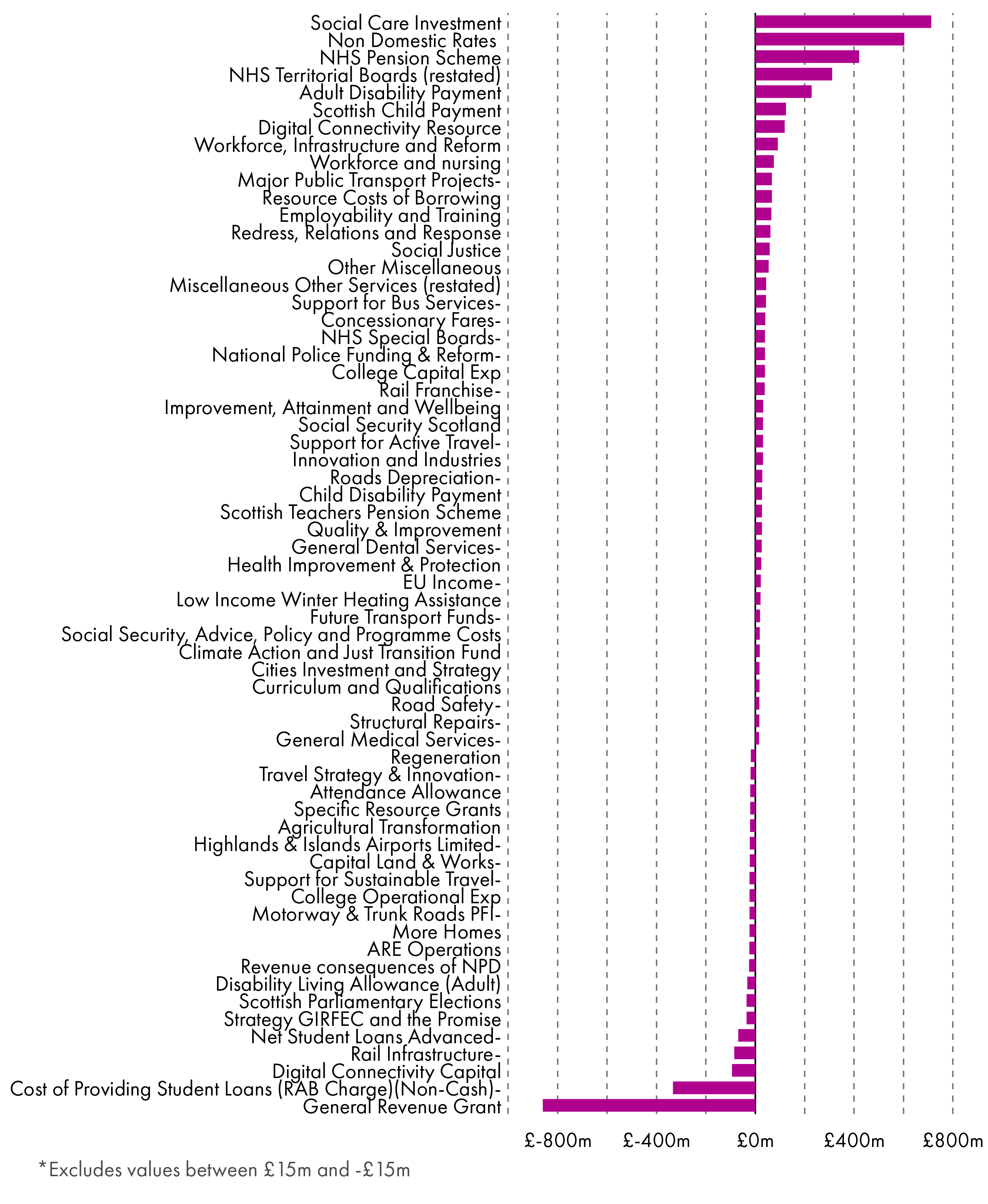

Figure 2 below shows the absolute change in Resource and Capital presented in the document between 2021-22 and 2022-23.

Portfolio allocations

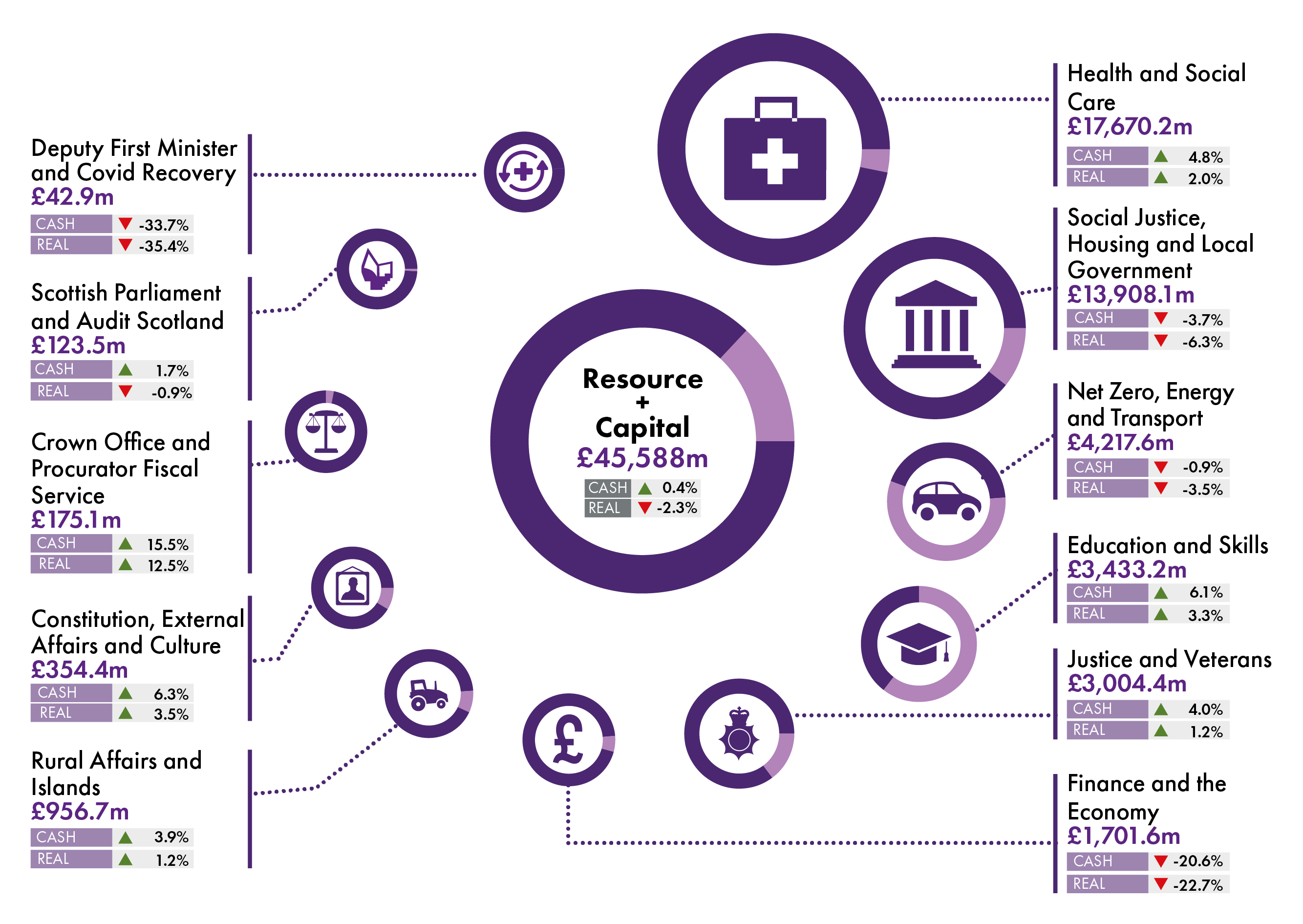

Resource and Capital allocation to portfolios for 2022-23, and how they have changed on the previous year, are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3 shows how these are allocated in cash and real terms in 2022-23. Key points to note are as follows:

Health and Social Care is the largest portfolio, comprising 39% of the discretionary spending power (Resource and Capital) of the Scottish Budget in 2022-23.

The next largest portfolio is Social Justice, Housing and Local Government which comprises just over 30% of the Resource and Capital spend combined, although this does not include Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI), which is AME but forms part of the local government settlement. Local government, and the settlement to local authorities will be the subject of a forthcoming SPICe briefing.

Six of the eleven portfolios increase in both cash and real terms - Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service; Constitution, External Affairs and Culture; Rural Affairs and Islands; Health and Social Care; Education and Skills; Justice and Veterans.

The largest real percentage increase (+12.5%) goes to Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal service.

Four of the eleven portfolios fall in both cash real terms - Deputy First Minister and COVID recovery; Social Justice, Housing and Local Government; Net Zero, Energy and Transport; Finance and the Economy.

The largest percentage real terms decrease in spending comes in the Deputy First Minister and COVID recovery portfolio, which falls by 35.4%.

Resource and Capital allocations

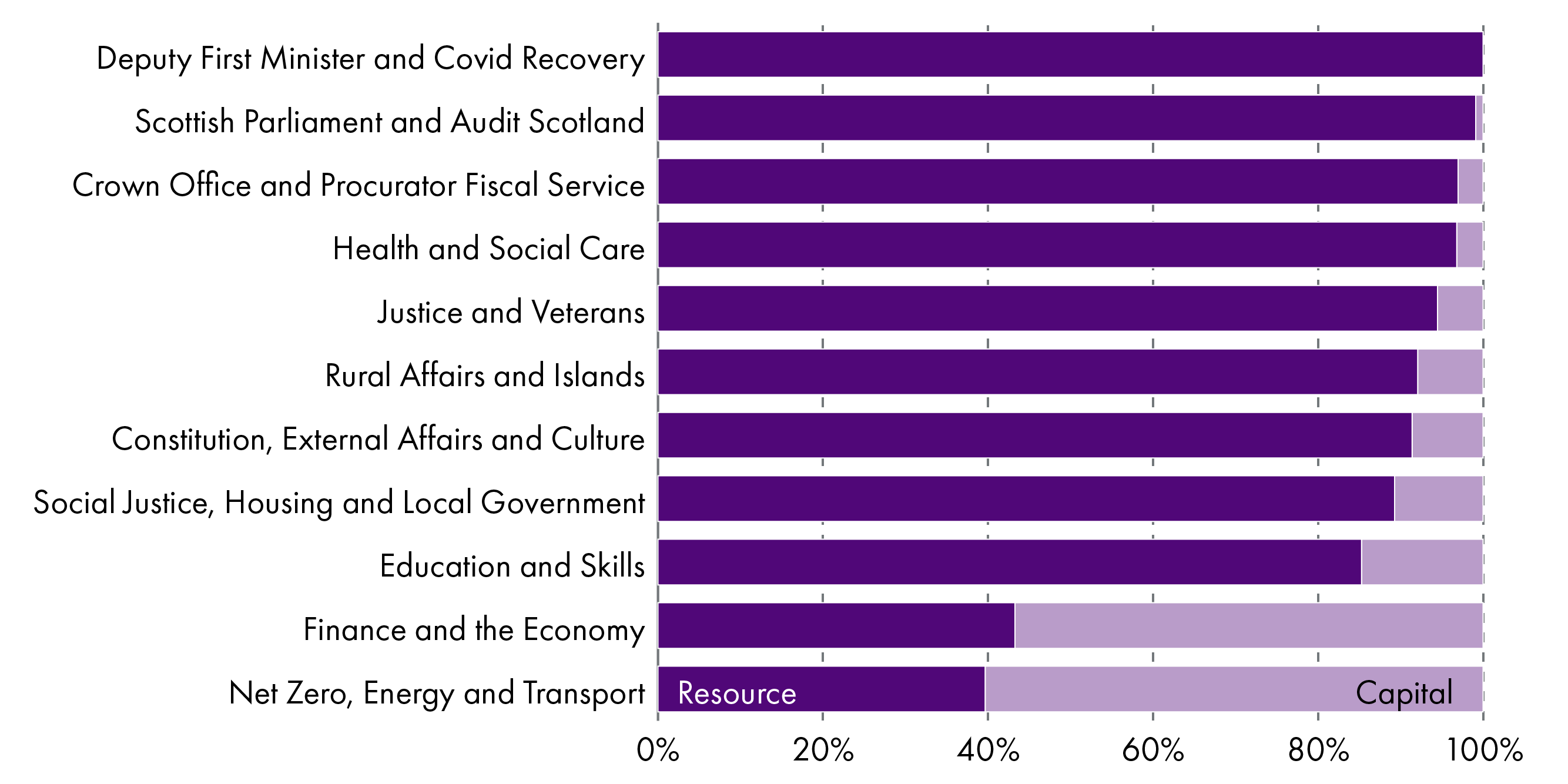

Figure 4 below shows the split between Resource and Capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments (the Resource budget).

Net Zero, Energy and Transport; and Finance and the Economy have the highest proportion of the budget comprising Capital expenditure (around 60%).

Social security

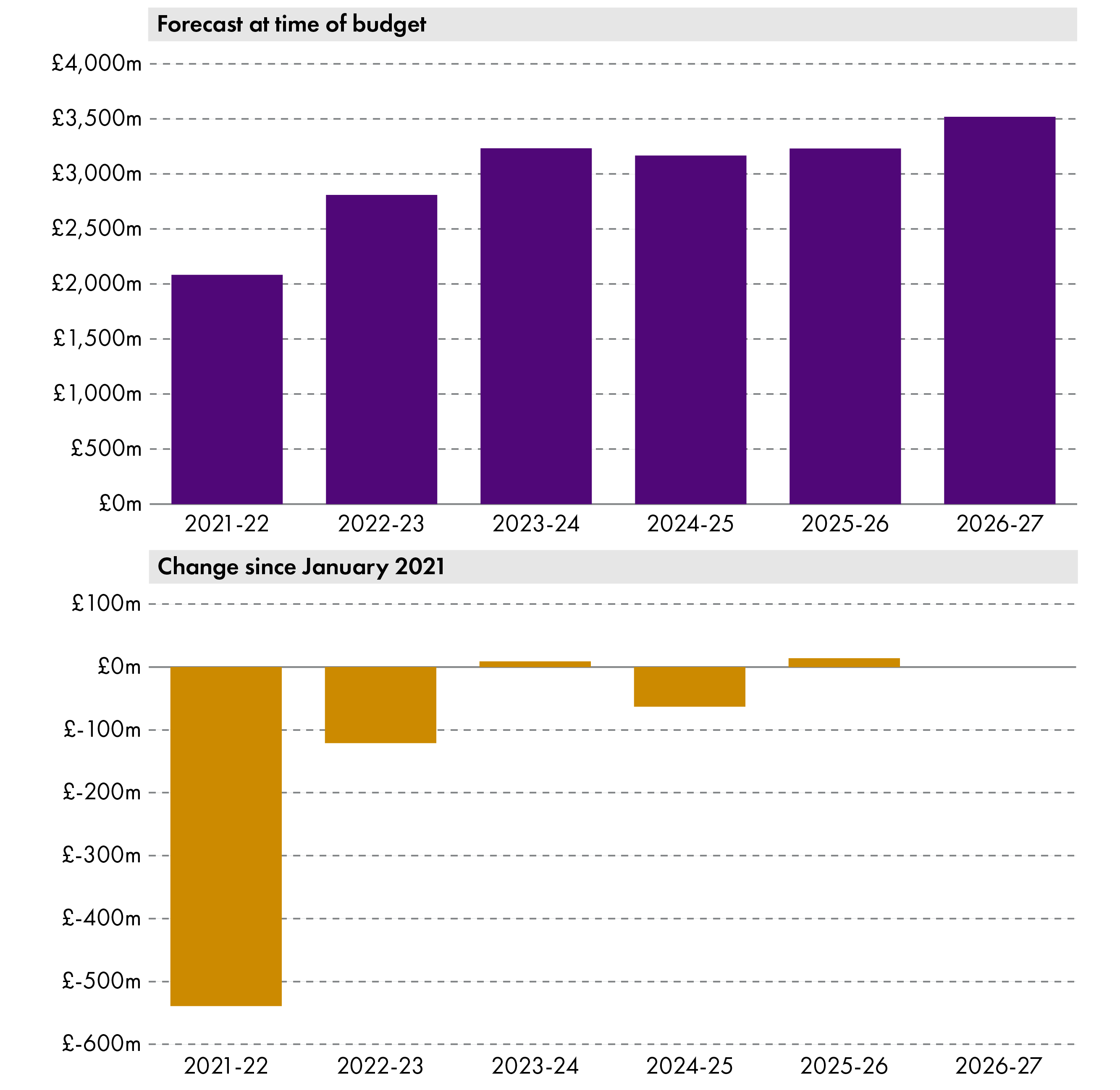

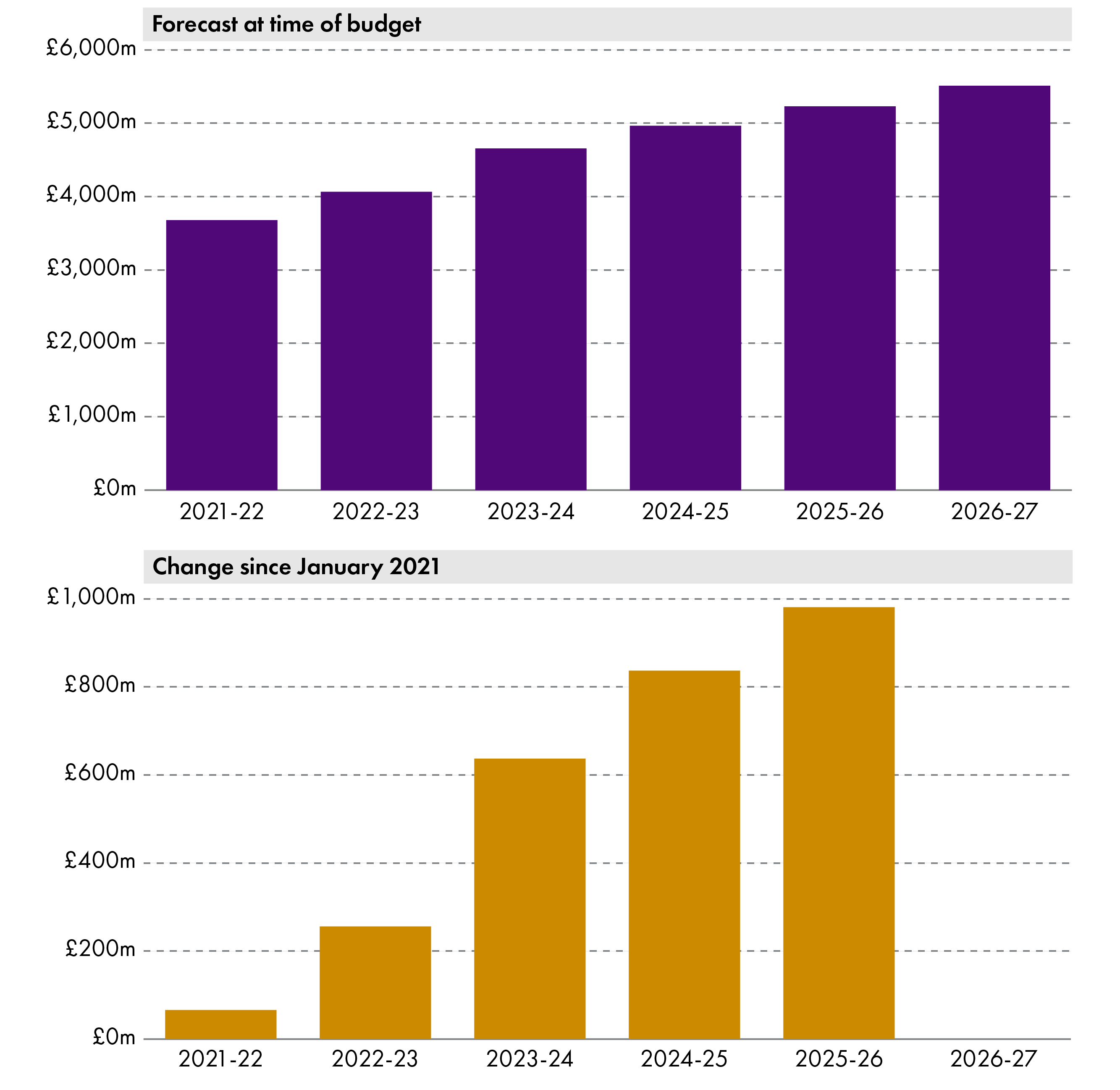

With the devolution of certain Social Security powers by Scotland Act 2016 came over £3 billion of spending power via an upward Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) to the Scottish Budget. However, it also brought with it increased budgetary risks, as any spending over and above the BGA must be found from other resources.

In 2022-23, the BGA added to the Scottish budget for social security is £3,587 million, but the forecast spend on social security is £4,065 million, a gap of nearly £500 million. Much of this difference is explained by the introduction by the Scottish Government of new social security payments which would not be expected to be covered by the BGA, because they are unique to Scotland, such as the Scottish Child Payment.

The SFC forecasts that by 2024-25, spending on social security in Scotland will be £750 million more than the corresponding funding received from the UK Government. This is further discussed in the section of this briefing on the SFC forecasts.

Figure 5 shows the various Social Security powers now devolved to the Scottish Parliament by size.

Largest Budget increases and decreases

Figure 6 presents the largest (real terms) proposed level 3 budget line increases and decreases in 2022-23 compared with the previous year.

The largest increases are in Social Care Investment and Non-domestic rates (NDR). The increase in NDR is perhaps not surprising given the reliefs provided in 2021-22. The local government general revenue grant (GRG) and Student loans see the largest real terms decreases. However as outlined in the local government section of the briefing, the Scottish Government guarantees the combined GRG and distributable NDRI figure, approved by Parliament, to each local authority. If NDRI is lower than forecast, this is compensated for by an increase in GRG and vice versa. Thus, although the GRG is showing a large decrease in Figure 6, this is compensated for by the large increase in NDRI and together, GRG+NDRI is flat in cash terms. Although of course, being flat in cash terms means this figure is a real terms reduction, in the context of rising prices.

Taxation policies and revenues

Income Tax

Income Tax proposals

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for Income Tax from April 2022 as part of the Scottish Budget 2022-23. These need to be approved by a Scottish Rate Resolution, which must precede Stage 3 of the Budget. Income Tax then cannot be changed during the financial year.

Very modest changes are proposed. The proposals involve increasing the basic rate threshold by 0.4% and increasing the intermediate rate threshold by 1.5%. All other thresholds are unchanged and there are no proposed changes to the rates.

The proposed increases to the basic and intermediate rate thresholds are below inflation, but have the effect of ensuring that the amount of income at which starter rate tax and basic rate tax is paid increases in line with inflation. For example, in 2021-22, the first £2,097 of taxable income was taxed at 19%. Under these proposals, the first £2,162 will be taxed at 19%, which is in line with the September 2021 consumer price index increase of 3.1%.

The proposed rates and bands are shown below.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,732 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,732 - £25,668 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,668 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,662 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2022-23)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The UK government sets the personal allowance and this is unchanged from 2021-22, at £12,750. The UK government has also frozen the higher rate threshold at £50,270 and plans to keep both the personal allowance and higher rate threshold at the current levels until 2025-26, as announced at the Spring 2021 UK budget2.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £50,270 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £50,270 - £150,000** | Higher | 40 |

| Above £150,000** | Additional | 45 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

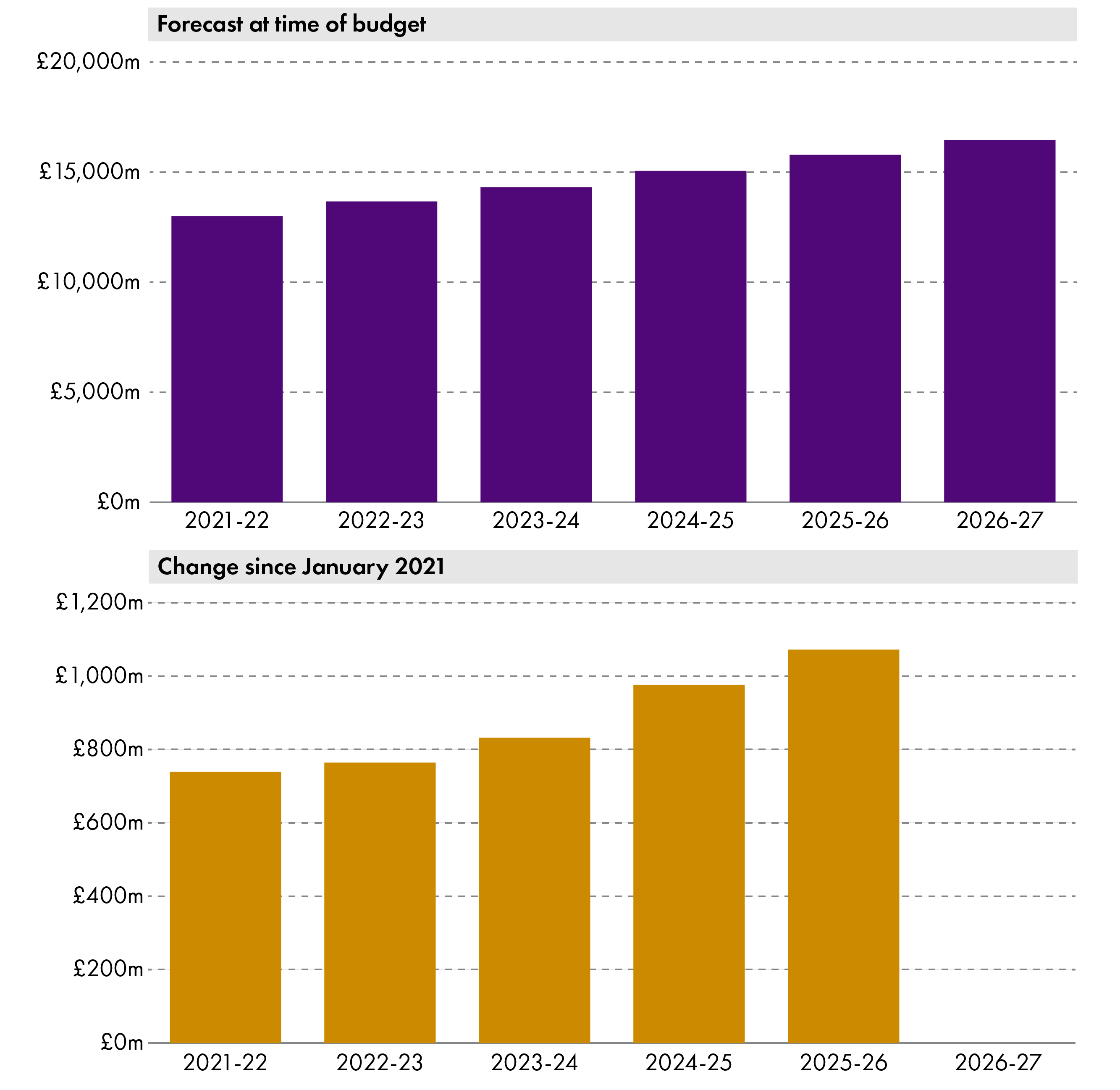

Income Tax revenues

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) forecasts that, with the proposals set out in the budget, non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income tax revenues will total £13,671 million in 2022-23. Forecasts for subsequent years, based on no change in policy other than uprating of taxation bands in line with inflation, are shown in Table 4.

| 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSND income tax | 13,671 | 14,313 | 15,056 | 15,790 | 16,445 |

The SFC estimates for 2022-23 are lower than had been forecast in August(£14,069 million), but higher than had been forecast in January 2021 at the time of the last budget (£12,907 million). This volatility in the forecasts reflects the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the specific timing of the forecasts relative to stages of lockdown and rollout of the vaccine programme. The forecast receipts influence the funding that the Scottish Government is able to allocate in 2022-23, although if the forecast turns out to be too pessimistic (or too optimistic), there will be reconciliations in future years.

The SFC estimates that the decision to freeze the higher rate threshold at £43,662 results in additional revenues to the Scottish Government of £106 million compared to what would have been raised if this threshold had been increased in line with inflation. As a result of this policy decision, more individuals will pay tax at the higher rate of 41%, as their earnings rise to take them above this threshold.

Impact on individuals

Income tax at various levels of earnings under the Scottish Government proposals is shown in Table 5. The proposals mean that all Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax in 2022-23 than they did in 2021-22. However, the differences are very small – only 65p over the year for those on incomes below £25,000, rising to just £4.57 per year for those earning above this.

When compared with rUK income tax policy, Scottish taxpayers earning less than £27,850 are paying just over £21 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. This accounts for 54% of all Scottish taxpayers. However, those earning more than £55,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

| Annual earnings | Scottish Government proposals 2022-23 income tax paid | Difference compared with 2020-21 | Difference compared with rUK |

|---|---|---|---|

| £ per year | £ per year | £ per year | |

| 15,000 | 464 | -0.65 | -21.62 |

| 20,000 | 1,464 | -0.65 | -21.62 |

| 25,000 | 2,464 | -0.65 | -21.62 |

| 30,000 | 3,507 | -4.57 | 21.50 |

| 35,000 | 4,557 | -4.57 | 71.52 |

| 40,000 | 5,607 | -4.57 | 121.50 |

| 45,000 | 6,925 | -4.57 | 439.10 |

| 50,000 | 8,975 | -4.57 | 1,489.10 |

| 55,000 | 11,025 | -4.57 | 1,593.10 |

| 60,000 | 13,075 | -4.57 | 1,643.10 |

| 65,000 | 15,125 | -4.57 | 1,693.10 |

| 70,000 | 17,175 | -4.57 | 1,743.10 |

| 75,000 | 19,225 | -4.57 | 1,793.10 |

| 80,000 | 21,275 | -4.57 | 1,843.10 |

| 85,000 | 23,325 | -4.57 | 1,893.10 |

| 90,000 | 25,375 | -4.57 | 1,943.10 |

| 95,000 | 27,425 | -4.57 | 1,993.10 |

| 100,000 | 29,475 | -4.57 | 2,043.10 |

National Insurance contributions

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are made by the UK government, but will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on NSND income tax to determine overall tax rates. NICs are linked to UK tax thresholds and the NIC rate drops from 12% to 2% at the UK higher rate threshold of £50,270. This means that Scottish taxpayers who earn between the proposed Scottish higher rate threshold (£43,662) and the rUK higher rate threshold (£50,270) will pay 41% income tax and 12% NICs on their earnings between these two amounts – a combined tax rate of 53%.

Devolved Taxes

This section sets out the impact of the Budget on devolved taxes other than Non-Savings Non-Dividend (NSND) income tax. The Scottish Government states that it has consulted with a ‘range of stakeholders’ including industry, tax professionals, research organisations and civic society ahead of producing the taxation proposals, and that there are three key themes which run through the consultation responses:

a desire among respondents for stability in the taxation system

continued focus on the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic

calls for reform of existing taxes, particularly Non-Domestic Rates and Council Tax.

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) has been devolved to the Scottish Parliament since April 2015 and replaced UK Stamp Duty Land Tax. This tax is applied to residential and non-residential land and building transactions where a chargeable interest is acquired, including commercial leases. There is also an Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) which applies to residential purchases of second homes. The Budget proposes that all existing rates and bands will be maintained in cash terms, including the bands for first time buyer relief and the ADS.

| Residential band | Thresholds | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nil rate | Up to £145,000 | 0% |

| First rate | £145,001 to £250,000 | 2% |

| Second rate | £250,001 to £325,000 | 5% |

| Third rate | £325,001 to £750,000 | 10% |

| Fourth rate | Above £750,000 | 12% |

The ADS rate of 4% will continue to apply to all transactions above £40,000. In addition to the rates for residential purchases, LBTT is also charged on non-residential purchases and leases, as per the thresholds and rates set out in Table 7 and 8 below. In the 2021-22 Programme for Government2, the Scottish Government pledged to review the ADS. The Budget proposal states that a call for evidence and views will shortly be launched by the Scottish Government, but that the review will be very limited. It will not consider whether ADS should continue, nor the overall impact of the policy, nor whether the rate should be changed, but instead will focus of the operation of the ADS.

| Non-residential sale band | Thresholds | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nil rate | Up to £150,000 | 0% |

| First rate | £150,001 to £250,000 | 1% |

| Second rate | Above £250,000 | 5% |

| Non-residential lease band | Thresholds | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nil rate | Up to £150,000 | 0% |

| First rate | £150,001 to £2,000,000 | 1% |

| Second rate | Above £2,000,000 | 2% |

Scottish Landfill Tax

Scottish Landfill Tax (SLT) is a devolved tax on the disposal of waste to landfill, which replaced UK Landfill Tax in Scotland from 1 April 2015 following the passage of the Scotland Act 2012 and the subsequent Landfill Tax (Scotland) Act 2014.

In the Budget the Scottish Government announced that the standard rate will rise by 2% and the lower rate by 1.6%, as set out in Table 9 below, which maintains consistency with the Landfill Charge in England and Northern Ireland. Landfill site operators can continue to contribute to the Scottish Landfill Communities Fund, a tax credit scheme. Landfill operators can contribute to the Communities Fund and receive a tax credit worth up to 90% of the value of their qualifying contributes. The 2022-23 Budget maintains the credit rate cap at a maximum of 5.6% of an operator’s tax liability.

In September 2019, the then Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform announced that full enforcement of the ban on sending biodegradable municipal waste to landfill would be delayed until 2025, in response to concerns that the only way local authorities could meet the deadline would be to export waste to England. In the Climate Change Plan 2018-2032 update 71, the Scottish Government clarified that this ban would be in effect from 31 December 2025.

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2022-23 % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard rate | £94.15 | £96.70 | £98.60 | +2.0% |

| Lower rate | £3.00 | £3.10 | £3.15 | +1.6% |

The Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

The Scottish Fiscal Commission's (SFC) main forecast publication, Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 20211, was published alongside the Scottish Budget for 2022-23. The SFC’s forecasts are an important component in determining the total budget available to the Scottish Government to spend in each financial year.

In this section, we summarise some of the key trends from the SFC’s detailed economic forecasts, and its forecasts for devolved taxes and social security.

Treatment of COVID-19 in forecasts

The SFC’s forecasts are based on a range of broad-brush assumptions about the outlook for the pandemic. Examples of assumptions include:

from April 2022 and into the longer term, it assumes COVID-19 will become endemic, continuing at a low baseline level again with the possibility of some periods of higher cases

after April 2022, it anticipates COVID-19 will begin to be managed through guidance and voluntary measures

international prevalence of COVID-19 will continue to affect supply chains and foreign tourism, both inbound and outbound, with the long-term effects continuing after 2021.

Overall, the forecast has assumed minimal restrictions applying in Scotland and the rest of the UK and that the vaccination programme will continue to result in a weakened link between cases, hospitalisations and deaths and therefore public health restrictions will remain minimal.

The SFC states that its forecasts were finalised before the emergence of the Omicron variant and note the following:

“Current information on the severity and likely implications for restrictions of Omicron is limited, but broadly we think it remains reasonable to assume the effects of Omicron fit within our central assumptions.”

It is highlighted by the SFC that any decision by Scottish Ministers to impose tighter public health restrictions than in England, that require assistance to businesses or individuals, could pose difficulties for the Scottish Budget.

The difficulties in forecasting a budget in the pandemic can perhaps be illustrated in a couple of examples:

the impact on the hospitality sector of recent advice from Public Health Scotland to defer Christmas parties, and the knock on effect on both revenues and, potentially, consumer spending

changing forecasts from the SFC for the funding required to deliver the Self-Isolation Support Grant, which (for 2021-22) rose from £6 million when forecast in January, to £19 million in the August forecast, and £32 million in the December forecast (and the final amount may be higher still as these latest forecasts were made prior to the emergence of Omicron).

GDP forecast

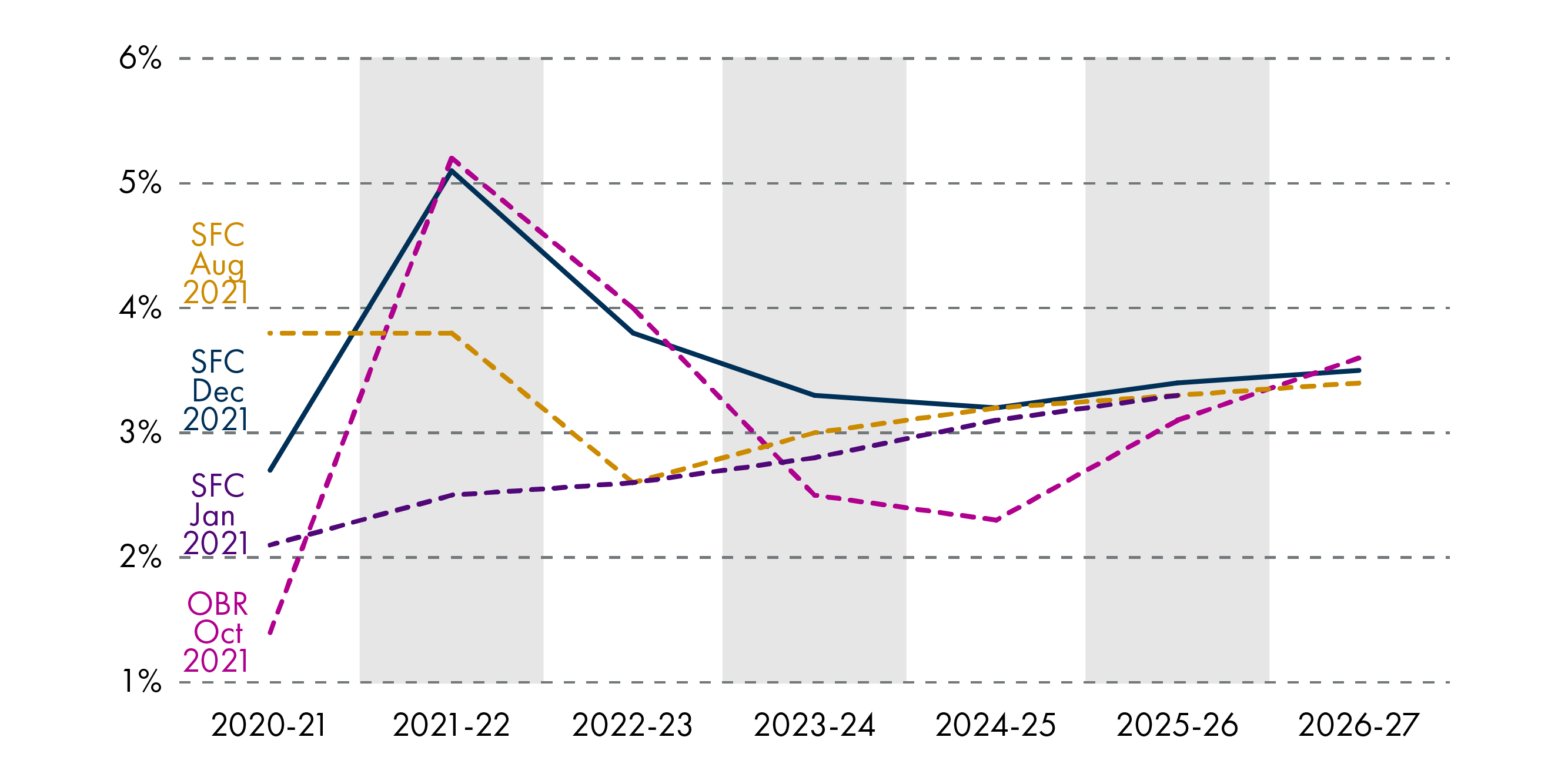

The SFC expects Scottish GDP to grow by 10.4 per cent in 2021-22, in line with its most recent estimate in August 2021, as shown in Figure 7. The SFC notes that this implies a return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity by the second quarter of 2022.

However, longer term GDP growth rates for 2025-26 have been adjusted down by the SFC, relative to the August 2021 and January 2021 forecasts.

It is worth noting the following factors that contribute to the GDP outlook:

Household disposable income is forecast to decrease due to increased inflation, and also because of higher taxes (including the Health and Social Care Levy, introduced by the UK government). The reduction in income puts pressure on the savings ratio and sees a decline in household consumption over the forecast period.

Business investment has been revised up due to the time-limited capital allowance super-deduction announced in the UK Budget in March 2021. Although the aggregate outlook for business investment is positive in the short term, there are differing prospects for business investment according to firm size and level of debt after the pandemic, with smaller firms more likely to be in debt and less likely to invest.

Trade is expected to have a neutral effect on GDP growth. This is because the recovery in exports due to the resurgence of global demand is balanced by the import-intensive nature of the increase in business investment and household consumption.

Looking longer-term the SFC highlights that falling labour market participation coupled with a slowdown in population growth means that it expects a decline in the size of Scotland’s labour force over the forecast period and falling employment by 2024. This will have important implications for forecasts of the economy and also Scottish tax revenues.

Wider economic factors

Employment

The SFC forecast sets out a more positive picture for employment in the economy compared to previous forecasts. The SFC suggests there is evidence that the domestic labour market may not be at capacity, as current labour shortages would imply. The SFC notes that economic participation is still below potential, and recruitment difficulties and record-high vacancies are largely a result of a post-lockdown adjustment across sectors.

The SFC now forecasts the unemployment rate will peak at 4.9 per cent in 2021 Q4. This is down from the peak forecasted in August 2021 of 5.4 per cent, and substantially lower than the January 2021 forecast where unemployment peaked at 7.6 per cent.

Inflation

Inflationary pressures have increased since previous forecasts in 2021, driven in part by high energy prices and global supply chain disruptions. The SFC expects CPI inflation to peak at 4.4 per cent in 2022 Q2, before then gradually returning to target (2%) by the second half of 2024. However, the SFC notes that there are significant risks to the outlook for inflation and interlinked interest rate movements:

“If inflation remains higher for longer, this could lead to a larger interest rate response from the Bank of England and have significant implications for the Scottish economy and households, including limiting credit and reducing house prices.”

The SFC’s inflation forecast is aligned with the OBR’s October 2021 UK inflation forecast.

| Per cent | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2021 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | |

| December 2021 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

Earnings

SFC’s perspective on earnings has varied over 2021, as show in Figure 9. In August 2021, the forecast increased from January 2021, in line with higher inflation. However, with more evidence of inflation being driven primarily by global energy prices rather than domestic factors, SFC now assumes the knock-on effect on nominal earnings will be lower than previously thought. As well as higher inflation, the forecast reflects factors such as National Living Wage and Minimum Wage increases and wage pressures because of labour shortages in particular industries.

In 2022-23, it forecasts nominal earnings growth to be moderate at 2.6 per cent. Higher inflation, combined with recent tax rises, sees the SFC predict that many households will see their real average earnings fall by 0.8 per cent in 2022-23.

Forecast comparison

Table 11 shows a comparison of GDP growth rates from a range of forecasters at a Scotland and UK level. The SFC’s outlook for Scotland is much more subdued than the OBR’s outlook for the UK. In 2022, Scotland’s growth rate is 2.2 percentage points below the UK rate.

| Per cent | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | ||||||

| SFC December 2021 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| FAI September 2021 | 6.5 | 4.8 | ||||

| UK | ||||||

| OBR October 2021 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| NIESR November 2021 | 6.9 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| BoE November 2021 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | ||

| HMT average of forecasters Nov 2021 | 7.0 | 5.0 | ||||

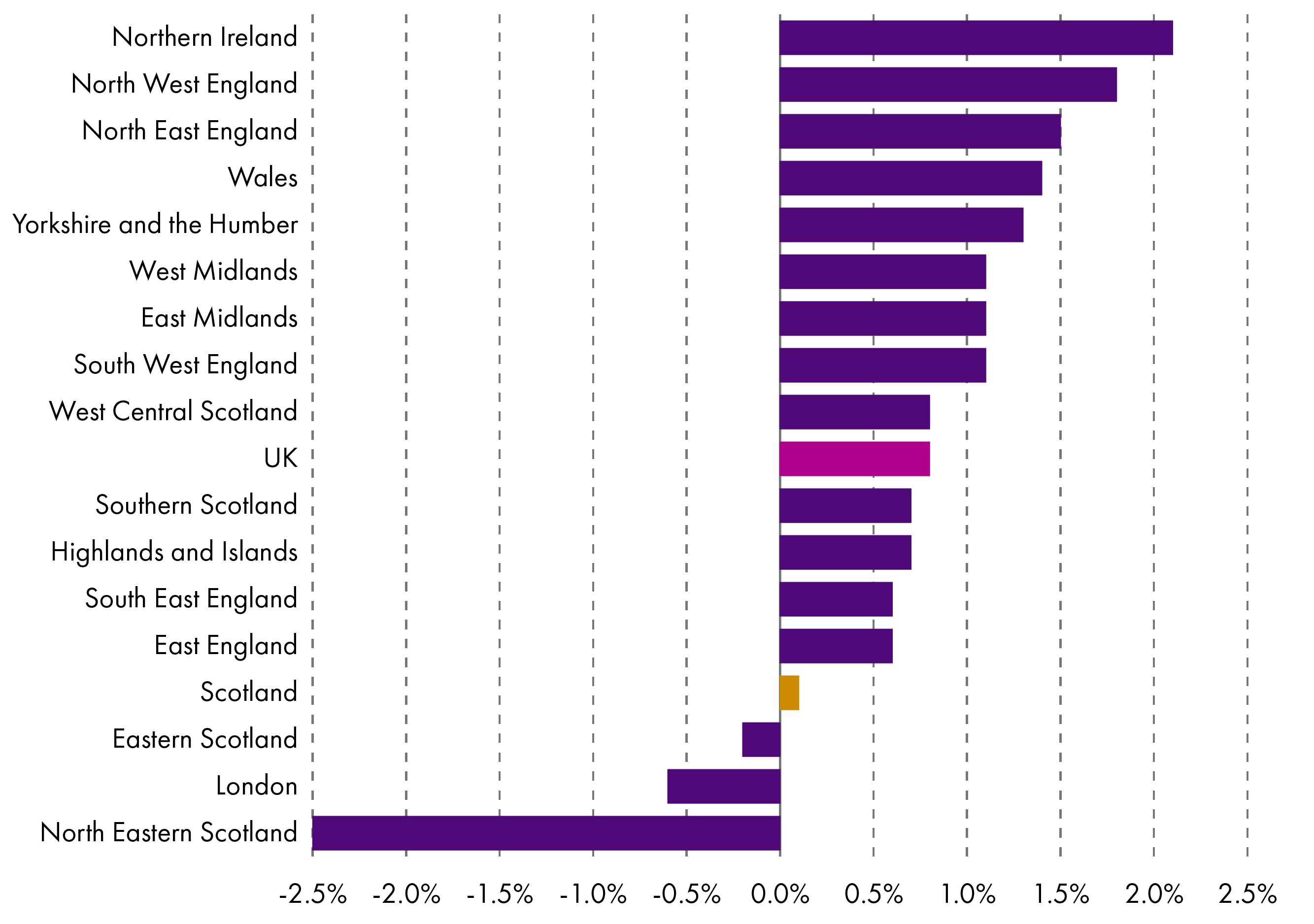

The SFC suggests that despite the pace of the recovery in Scotland, there is some evidence that the Scottish economy has been lagging behind the rest of the UK. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, Scottish GDP, employment and earnings have recovered more slowly than in the UK.

Analysis by SFC of PAYE data suggest that highly-paid finance and insurance sector employment in England is largely driving this gap. The largest relative fall in Scottish sectoral GDP is in mining and quarrying, reflecting both the importance and the longer-term decline of oil and gas support services in Scotland. The chart below extracted from SFC’s analysis illustrates the scale of impact in Scotland’s North East. These types of dynamics have important implications for forecasts of the Scottish economy and tax revenues.

Forecasts for devolved taxes

This section gives an overview of the latest forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission for revenues from devolved taxes, and how these have changed since the forecasts which were published alongside the last Scottish Budget in January 20211. In an earlier section of the briefing we look in more detail at the Scottish Government's tax policies.

The significant changes in the economic context since the last forecasts were produced in January 2021 mean that expected revenues from most devolved taxes are materially higher than was expected at the time of the last Budget in all years, with the exception of Non-Domestic Rates. In total, revenues from devolved taxes are expected to be £312 million higher in 2021-22 and £777 million higher in 2022-23 compared to the forecast for those years made in January 2021.

In 2021-22, the difference is driven by higher than expected receipts from Income Tax (£739 million) and Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (£134 million), largely offset by lower than expected receipts from Non-Domestic Rates (-£597 million).

The pattern is similar in years 2022-23 and beyond – total expected receipts from devolved taxes are considerably higher than was forecast in January 2021, with expected receipts from Income Tax the main driver.

Non-Savings Non-Dividend Income tax

Revenues from NSND Income Tax are forecast to rise by around 5% per year over the first four years of the forecast period (5.1% in 2022-23 and 4.7% in 2022-23), and to grow by 4.1% between 2025-26 and 2026-27. This compares to growth of 2.4% per year between 2018-19 to 2019-20, the most recent years we have outturn data. Compared to the January 2021 forecast, revenues from NSND Income Tax are expected to be significantly higher over the forecast years. Revenues are expected to be £739 million higher in 2021-22 than forecast in January, and then a total of £3.6 billion higher over the next four financial years. However, it is worth bearing in mind that the 2021-22 Budget was made in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic – the SFC forecast in January 2021 expected receipts for devolved taxes to be a total of £5.5 billion lower between 2020-21 and 2024-25 than had been expected in the previous, pre COVID-19 forecast (February 2020), so the increase compared to January 2021 should be understood in this context.

The main driver of these differences is the updated economic context since the last forecast, and specifically the faster than expected recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and the more muted impact on the labour market, coupled with significant inflation projected over the period. The SFC note that ‘fiscal drag’ is expected to contribute to the growth in expected receipts. Fiscal drag is where tax thresholds rise less than inflation, resulting in a greater proportion of taxpayers paying the higher rates than might have been expected were inflation lower.

Despite these higher than expected revenues from NSND Income Tax, the SFC forecast expects an increasingly negative position for Scottish Income Tax once reconciliation takes place. This is because income tax revenues in the rest of the UK are expected to grow more quickly than in Scotland, resulting in larger block grant adjustments to the Scottish Budget. The SFC discusses the emerging negative Income Tax position which is being driven by several factors long-term factors:

Scotland’s changing demographics, and a population which is aging faster than the UK as a whole.

Lower labour market participation in younger age groups, as a result of growing enrolment in tertiary education.

Slower growth in average earnings in Scotland, particularly in the North East of Scotland relating to oil and gas activity.

More rapid growth in average earnings in the rest of the UK, partly driven by strong growth in financial services.

Non-Domestic Rates

Forecast revenue from NDR is lower in 2021-22 (£539 million) and 2022-23 (£121 million) than expected at the time of the January 2021 forecast. The majority of the difference in 2021-22 (£518 million) is due to the March 2021 announcement of a 9 month extension to rates relief for hospitality, leisure and aviation sector, and the one year delay to removal of independent school exemption. Policy changes announced in the 2022-23 Budget proposal reduce expected NDR income by £96 million in 2022-23, and by around £40 million in each subsequent year. Data and modelling changes also reduce expected income in the forecast years, but these are mostly offset by an expected increase in receipts due to the expected higher inflation over the period.

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax

The forecast for LBTT revenues in each year has increased since the January 2021 forecast, largely as a result of the improved economic context but also reflecting data from Revenue Scotland. This shows a higher average selling price than expected, resulting in more transactions qualifying for the higher rates of LBTT. The balance between residential and non-residential LBTT receipts is expected to remain broadly stable over the forecast period, with residential transactions amounting to around 72% of total LBTT revenues. However, the forecasts assume that revenues from the Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) will grow more slowly than other components of LBTT – in 2020-21 ADS amounted to 31% of total residential LBTT, but this is projected to fall to 23% by 2026-27.

Scottish Landfill Tax

Revenues from SLT are expected to be higher throughout the forecast period than in the January 2021 forecast, reflecting greater volumes of waste being sent to landfill than was expected. From 2022-23, the SFC expects greater incineration capacity than in its previous forecast, as the Grangemouth incinerator is now expected to operate at a slightly higher capacity. The two areas of uncertainty in relation to the SFC forecast are the timing of the biodegradable municipal waste ban, and the capacity of incineration plants.

Comparing SFC tax forecasts with Block Grant Adjustments

In the 2022-23 Budget, for the first time since the Scotland Act 2016 powers were introduced, the Budget shows that the revenues expected from devolved taxes will not be enough to offset the amount taken off the block grant to account for this devolution of powers. That is, the SFC tax forecasts are lower than the tax block grant adjustment (BGA).

As shown in Table 12, this is the result of income tax revenues expected to be lower than the equivalent BGA.

| SFC revenue forecast£m | Block Grant Adjustment£m | Net position£m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income tax | 13,671 | -13,861 | -190 |

| LBTT | 749 | -664 | 86 |

| SLfT | 101 | -82 | 18 |

| Total tax position | 14,521 | -14,607 | -86 |

Overall, tax revenues from the devolved taxes are expected to be £86 million lower than the BGA. For income tax specifically, revenues are expected to be £190 million lower than the BGA. This is despite the Scottish Government having adopted a tax policy that sees Scottish taxpayers in aggregate paying around £500 million more than they would do if Scotland had the same income tax policy as the rest of the UK.

The different tax policy is not expected to generate enough revenue to offset the deduction that is made from the block grant. That deduction reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax if it had retained the same tax policy as the rest of the UK and if Scotland’s per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK.

The gap arises because Scotland’s economic performance (in terms of earnings growth and employment) has been weaker and because Scotland has a different taxpayer mix (both in terms of numbers paying tax and also in the mix of higher and lower rate taxpayers). See the SPICe briefing on Income Tax for a fuller discussion of these issues.

These factors mean that the differential income tax policy has not generated enough revenue to offset the BGA for income tax. On the basis of current forecasts, this position is expected to deteriorate over the next few years, with a gap of £417 million in the income tax net position by 2026-27.

It is worth noting that this assessment is currently based on forecasts by both the SFC (for revenues) and the OBR (for the BGA). Both of these are likely to change, which could either make the net position worse, or could act to reduce the gap, or even result in a positive net position. It is also worth noting that the net positions for LBTT and SLfT are currently both positive, so revenues from these two devolved taxes are helping to partially offset the negative position for income tax.

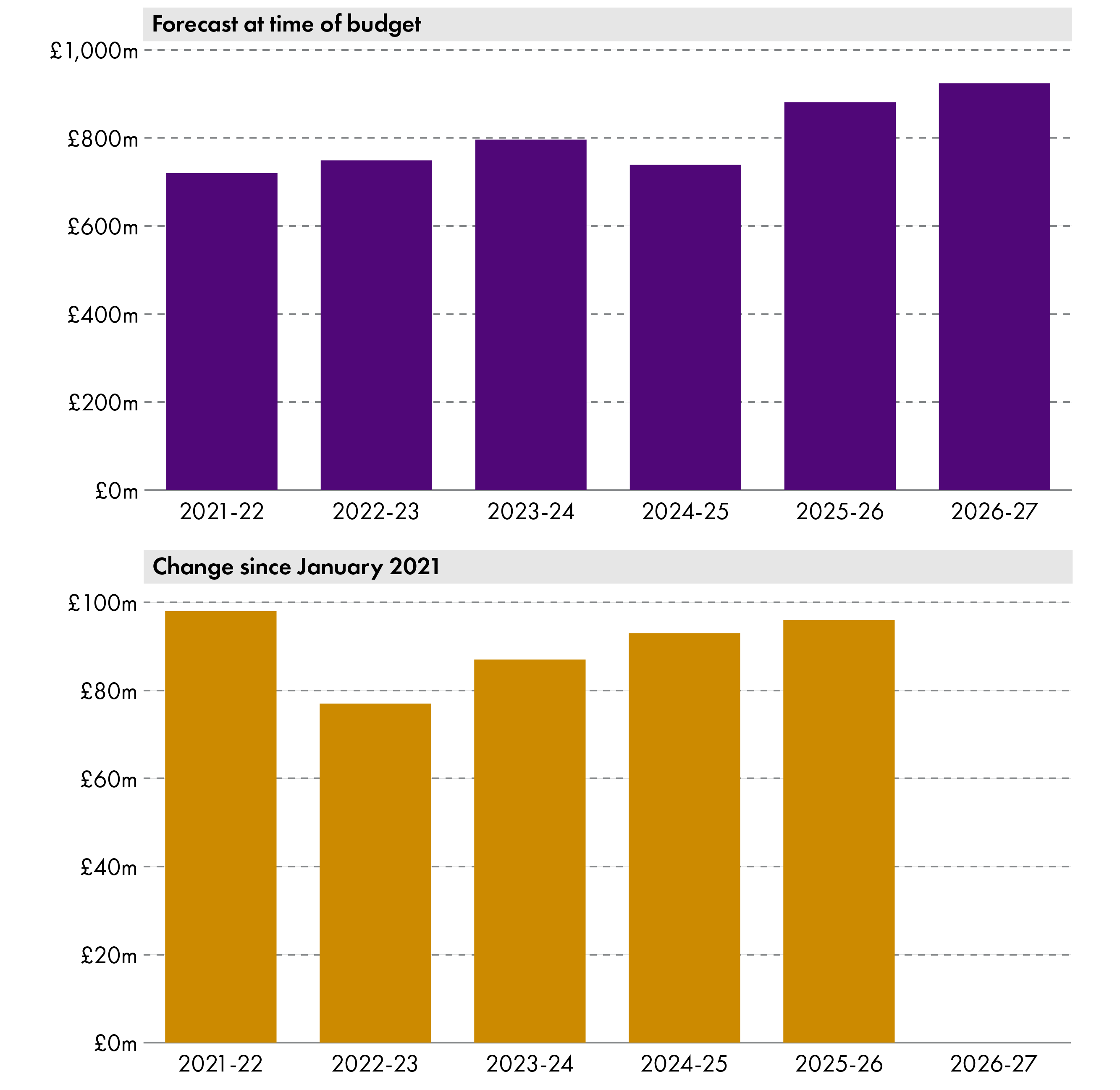

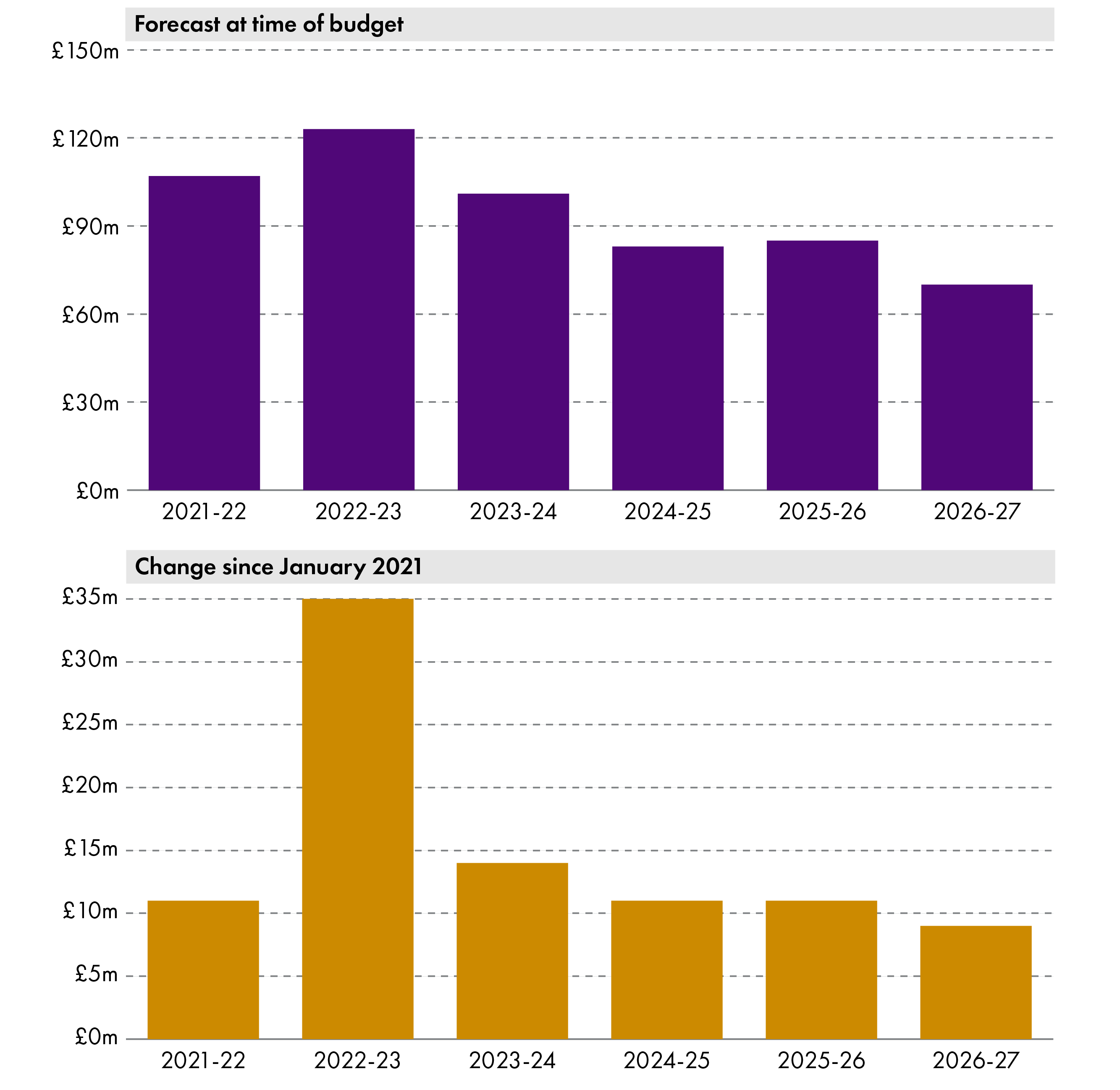

Social security forecasts

The expected cost of delivering the devolved social security benefits in Scotland has increased for every year since the January 2021 forecast, and will be nearly £1 billion higher in 2025-26 than previously expected. The increase is driven by new social security payments introduced by the Scottish Government, and by the impact inflation will have on some payments. The most significant policy difference is the increase to the Scottish Child Payment. This is expected to result in additional costs of £103 million for 2022-23, and around £185 million a year thereafter. The Adult Disability Payment is expected to result in an additional £38 million of expenditure in 2022-23, rising to over £500 million in additional expenditure by 2026-27.

Capital and infrastructure

The 2022-23 capital budget from HM Treasury is £4,469 million, a 10% reduction in cash terms compared with 2021-22. The Scottish Government plans to increase the amount available for capital expenditure in 2022-23 through a combination of mechanisms:

Using maximum borrowing powers (£450 million).

Using Financial Transactions (FT) funding from the UK Government and recycling receipts received from previous loans made using FTs (£466 million).

Drawdown from the Scotland Reserve (£179 million).

Capital allocations from the UK government in respect of the Network Rail funding arrangements (£643 million).

City Deal funding (£100 million).

Receipts from the Fossil Fuel Levy (£44 million).

These additional financing sources will mean total capital investment in 2022-23 of £6,351 million, which is 3.9% higher than the equivalent planned capital spending for 2021-22 (£6,110 million). However, some of the funding sources outlined above are ring-fenced for specific purposes e.g. Network Rail, City Deals, renewable energy (Fossil Fuel Levy receipts). This limits the discretion of the Scottish Government to a certain degree. Further detail on the sources of funding for infrastructure spending is given below.

The Scottish Government’s National Infrastructure Mission set out plans to increase annual infrastructure investment so that annual investment is £1.56 billion higher in 2025-26, when compared with a 2019-20 baseline. In the Medium Term Financial Strategy1 (MTFS) that was published alongside the Budget, the Scottish Government notes that the capital budgets set out in the UK government’s 2021 Spending Review2 were lower than the amounts that had been modelled in the Scottish Government Capital Spending Review3 of February 2021. The Scottish Government notes in the MTFS that it still expects to be able to meet the level of investment set out in the National Infrastructure Mission, but that lower-than-anticipated capital allocations from the UK government could constrain its ability to meet net zero targets.

The Scottish Government also notes concern that Levelling Up Fund investments could divert funds from future Scottish Government capital grants which could threaten fulfilment of the National Infrastructure Mission target.

In recent years, the Scottish Government has used revenue financing to increase the level of infrastructure investment that can be achieved through the capital budget alone. Revenue financing means that the Scottish Government does not pay the upfront construction costs, but is committed to making annual repayments to the contractor, typically over the course of 25-30 years. The Scottish Government previously used a model known as the Non-Profit Distributing (NPD) model but has proposed introducing a modified version of the NPD model, known as the ‘Mutual Investment Model’ (MIM). This shares a number of features with NPD but is adjusted so that it meets the requirements for such investment to be treated as private sector investment and therefore paid for out of revenue budgets over a longer timeframe. The budget document does not make any reference to the use of MIM, although the MTFS refers to its possible use for funding of the A9 dualling programme. The MTFS also includes plans for the value of revenue financed projects to increase to £1 billion per year by 2024-25.

Borrowing powers

The Scottish Government is able to borrow up to £450 million in each year for capital investment, up to a cumulative total of £3 billion. The Budget sets out plans to borrow the maximum £450 million in capital borrowing to support infrastructure expenditure in 2022-23. The MTFS projections suggest lower levels of capital borrowing in future years and that the total stock of debt will reach £2,730 million by the start of 2026-27. The SFC notes that lower planned borrowing in future years is required in order to remain within the capital borrowing limit, while also allowing the Scottish Government to meet its self-imposed rule of ensuring a contingency of £300 million remains available in 2026-27 (as set out in the MTFS).

The Scottish Fiscal Commission is required to assess the reasonableness of the Scottish Government’s borrowing plans. They assessed the Scottish Government’s capital borrowing plans as reasonable but noted that the Scottish Government usually plans to borrow the maximum £450 million in the budget, but actual borrowing is typically lower than planned for. The SFC explains that:

“..the Government has typically reduced planned borrowing in-year to ensure there is not a large underspend which breaches the Scotland Reserve limit. Borrowing can be reduced to either manage capital underspends, or remove capital funding from the Scotland Reserve, creating more space for resource funding.”

The SFC also noted that the “borrowing plans have been made within the context of expected reductions to Block Grant funding in future years and the slowing of planned borrowing will further reduce capital funding over the forecast period.”

Financial transactions

The 2022-23 Budget includes £466 million for financial transactions (FTs), including repayments. These FTs relates to Barnett consequentials resulting from a range of UK government equity/loan finance schemes (primarily the UK housing scheme, Help to Buy) and have been a regular source of funding since 2012-13. The Scottish Government has to use these funds to support equity/loan schemes beyond the public sector, but has some discretion in the exact parameters of those schemes and the areas in which they will be offered. This means that the Scottish Government is not obliged to restrict these schemes to housing-related measures and is able to provide a different mix of equity/loan finance.

For 2022-23, a total of £145 million (gross) in financial transactions has been allocated to housing-related schemes. The Scottish Government is also providing equity/loan finance support in areas other than housing. In 2022-23, £206 million (gross) in FTs will also be used to provide upfront capitalisation for the Scottish National Investment Bank.

Individual tables in the budget document show the following profile for financial transactions.

| Portfolio | £ million |

|---|---|

| Health and Social Care | 10.0 |

| Social Justice, Housing and Local Government | 150.0 |

| Finance and Economy | 284.6 |

| Education & Skills | 22.1 |

| Net Zero, Energy and Transport | 60.3 |

| Total | 527.0 |

The Scottish Government will be required to make repayments to HM Treasury in respect of these financial transactions. These repayments will be spread over 30 years, reflecting the fact that the majority of FT allocations relate to long term lending to support house purchases and the construction sector. The repayment schedule is based on the anticipated profile of Scottish Government receipts. A repayment to HM Treasury of £25 million in respect of FTs is scheduled for 2021-22.

Revenue financing and the 5% cap

Annual repayments resulting from revenue financed projects and borrowing come from the Scottish Government’s resource budget. The Scottish Government has previously committed to spending no more than 5% of its total resource budget (excluding social security) on repayments resulting from revenue financing (which includes NPD/hub, previous PPP contracts, regulatory asset base (RAB) rail investment) and any repayments resulting from borrowing. Previous budget documents have shown performance against this commitment, but no information is provided in the document this year and it is not mentioned in the MTFS. This suggests that the commitment may have been shelved. The lack of any plans to use revenue financing for infrastructure investment in 2022-23 will mean little upward pressure on repayments in the short-term, although future plans for revenue financing could mean an increase in repayments related to revenue financing in future years, along with increased borrowing repayment.

Local government

This section of the briefing sets out a high-level summary and analysis of the local government budget for 2022-23. The Local Government Finance Circular, which details the provisional allocations to individual local authorities, is due for publication on Monday 20 December. A dedicated SPICe briefing containing detailed analysis of these allocations and other figures will follow. There is a delay this year between the publication of the Scottish Government Budget and the publication of the Local Government Finance Circular. This is due to some key education statistics, which are used in the local government distribution formula, not being published until mid-December.

Different totals depending on what is included

The local government budget settlement for 2022-23 is £11,141 million. This is mostly comprised of General Revenue Grant (GRG) and Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI), with smaller amounts for General Capital Grant and Specific (i.e. ring-fenced) Resource and Capital grants. This figure represents a £33 million increase over the year, translating as a cash increase of 0.3%, or a real terms reduction of 2.4% (or -£268 million).

The Scottish Government guarantees the combined GRG and distributable NDRI figure, approved by Parliament, to each local authority. If NDRI is lower than forecast, this is compensated for by an increase in GRG and vice versa (this occurred between the Finance Circular 2 (10 March 2020) and the Finance Circular 4 (30 March 2020)) . The combined Budget figure for GRG+NDRI in 2022-23 remains the same over the year in cash terms (£9,739 million). In real terms, this is estimated to be a reduction of 2.7% (or -£264 million).

Once revenue funding which is transferred from other portfolios to local government (but still included in the totals within the Finance Circular) is included, the total is £12,474 million. This represents a cash increase of £854 million over the year (7.3%) or a real terms increase of £539 million (4.5%). This is the figure highlighted by the Scottish Government in Chapter 1 of the Budget document.

Much of this increase is funding for additional teachers and support staff, care at home, delivering a £10.50 minimum wage for adult social care staff, as well as other health and social care funding from the Health budget. Furthermore, once a number of funding streams attached to particular portfolio policy initiatives, but outside the totals in the Finance Circular are included, overall Scottish Government funding for local government rises to £13,215 million.

Capital allocation

In addition to the revenue budget, used to pay for public services and day to day costs, local government also receives a capital budget. This is made up of general (i.e. discretionary) and specific (i.e. ring-fenced) grants. Overall, the total capital budget sees a real terms increase this year of 5.2%, or £32 million. This is driven by an increase in the General Capital Grant as well as an additional £30 million for the capital costs associated with the expansion of free school meals.

The ask for multi-year local government finance settlements

In a letter sent to the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee the day before the Budget statement, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance confirmed the Budget document would not contain details of multi-year settlements for local authorities. This has been a major ask of local government for a number of years, most recently expressed in the Committee’s budget letter to the Government1. The Cabinet Secretary responded to the Committee's letter on 8 December2, stating:

“We are committed to providing local authorities with as much certainty as we can to help their long-term financial plans. In this respect, the UK Government’s spending review for the next 3 years does indeed enable us to embark on our own spending review to provide the certainty we all aspire to.”

The Budget document mentions the Spending Review Framework3 published alongside the budget which sets out the next stage of this process. This is discussed elsewhere in this briefing.

Council Tax

Local authorities raise some of their income through Council Tax. In 2019-20, Council Tax receipts amounted to £2.5 billion, or 20% of total local government net revenue funding.

During last year’s Budget announcement, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed that, subject to approval from local authorities, Council Tax would be frozen at 2020-21 levels. £90 million was made available to councils to compensate for this, and it was confirmed during Stage 3 discussions that this would be “baselined” in the 2022-23 Budget.

There is no mention of a council tax freeze in the Budget this year, however. Instead, the Scottish Government states that for 2022-23, “councils will have complete flexibility to set the Council Tax rate that is appropriate for their local authority area”. The appetite of Councillors to raise significant revenues from council tax, however, may be tested by the local authority elections of May next year.

COSLA’s pre-budget lobbying

COSLA published their Live Well Locally1 lobbying document in mid-November. Looking ahead to the Budget, they argued that in order to “survive” in 2022-23, the total revenue settlement for local government needed to be at least £12,075 million (increasing from £11,003 million in 2021-22). Given the actual figure announced in the Budget document was £11,795 million, it seems likely that the debate around local government finance2 will rumble on for some time to come.

Indeed, a few hours after the Budget was presented, COSLA published their initial response3. Although acknowledging increases to both the revenue and capital settlements, they argue that much of these additions relate to Scottish Government national commitments which, they believe, will be considerably more expensive for local authorities to deliver than the Budget document assumes. COSLA calculates that these policy commitments and the resulting pressures will cost local government an extra £891 million, so £100 million more than the cash increase of £791 million set-out in the Budget document.

The Spending Review Framework and Medium Term Financial Strategy

The Scottish Government also published a couple of documents looking beyond next year - namely the Medium Term Financial Strategy1 and the Spending Review Framework2. The Finance and Public Administration Committee is planning work on these in the new year, so further briefing material will be produced at that time, to support committee scrutiny.

The Medium Term Financial Strategy is meant to be published in May but was delayed by the Scottish election. It is anticipated that the MTFS will revert back to its normal May publication date in 2022, and be published alongside the Spending Review.

The document states that:

The purpose of the MTFS is to examine the medium-term sustainability of Scotland’s public finances, with a focus on the management of fiscal risk within existing constitutional and fiscal constraints. It also sets the medium-term context to annual budget decisions and the Resource Spending Review framework by presenting funding and spending scenarios over a five-year period.

The Spending Review Framework set out consultation questions from the Scottish Government for its upcoming Spending Review. This is expected to run until 27 March 2022, with the Spending Review due in May 2022.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee is also running a consultation process on the Spending Review Framework, which will run until late January, and be followed by evidence sessions and a response to the Scottish Government consultation.

This will be the first multi-year Resource Spending Review since 2011, and will set out spending plans for the remainder of this parliamentary term. The Framework documents sets the scene for this review and ask questions for public consultation, prior to the publication of the Spending Review plans in May 2022. The questions which the Scottish Government is seeking responses on are very high level and are as follows:

Whether the following priorities for guiding the Spending Review are the right ones:

to support progress towards meeting our child poverty targets

to address climate change

to secure a stronger, fairer, greener economy.

Whether the following primary drivers of public spending over the Spending Review period are correct and whether others should be added:

changing demographics

demand on the health service

public sector workforce

inflation.

Views on the following, or other ways in which to get best value out of public spending:

improving cross-government collaboration

public service reform

prevention and invest to save initiatives

the public sector workforce

better targeting

targeted revenue raising

Views on equality and human rights impact which should be considered in the Spending Review and views on how best to continue engagement with people and organisations after the Resource Spending Review.

A green recovery, carbon assessment of the budget and capital taxonomy

A green recovery and a just transition

As in recent budgets, the response to the climate emergency and the aim of a just transition feature prominently in the Budget for 2022-23. Key announcements include:

£1.4 billion to maintain, improve and decarbonise Scotland’s rail network.

The first £20 million of the £500 million Just Transition Fund will be spent to identify key projects to accelerate the development of a decarbonised economy in NE Scotland.

£414 million for energy efficiency and low carbon, renewable heat. This includes £160 million for individuals making home energy efficiency improvements and to tackle fuel poverty, and £60 million for large scale heat decarbonisation projects.

£150 million in active travel.

£53 million for industrial decarbonisation projects, including £20 million for the energy transition fund in NE Scotland.

£23.5 million for the Green Jobs Fund.

£6 million for the Climate Justice Fund.

Most of these major funding announcements, such as the £500 million ten year Just Transition Fund, had already been announced in the 2021-22 Programme for Government1 (PfG) or earlier. The Budget document did announce the first £20 million of investment as part of the Just Transition Fund, the first £414m million as part of the already announced £1.8 billion five year energy efficiency programme, an increase in Active Travel investment to £150 million (a step towards the £320 million target announced in the PfG), and a further £23.5 million investment in the already announced £100 million green jobs fund. The £1.4 billion investment in rail improvements includes the decarbonisation of the Barrhead corridor, the East Kilbride corridor and electrification of the Fife and Borders rail lines, all of which were outlined in the PfG as part of the £5 billion investment in rail over this Parliament. So, while there is more detail on how these five year programmes will be delivered, there is not a huge amount of new policy.

Commenting on the commitments in the PfG, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) noted that the policy and funding commitments support the Scottish Government emission reduction ambitions only “to some extent”.2 The CCC also noted that:

“A significant proportion of the Scottish Government’s ambition for 2030 rests on carbon capture and storage (CCS), but with the Scottish CCS cluster announced as only a ‘reserve project’, a decision must be made about whether to continue to plan for CCS and removals to contribute to the 2030 target at the same scale.”

In the foreword to the Budget document, the Cabinet Secretary notes that this budget is “transitional”, and that the Resource Spending Review in May 2022 will set out the Government’s spending plans to deliver key commitments.

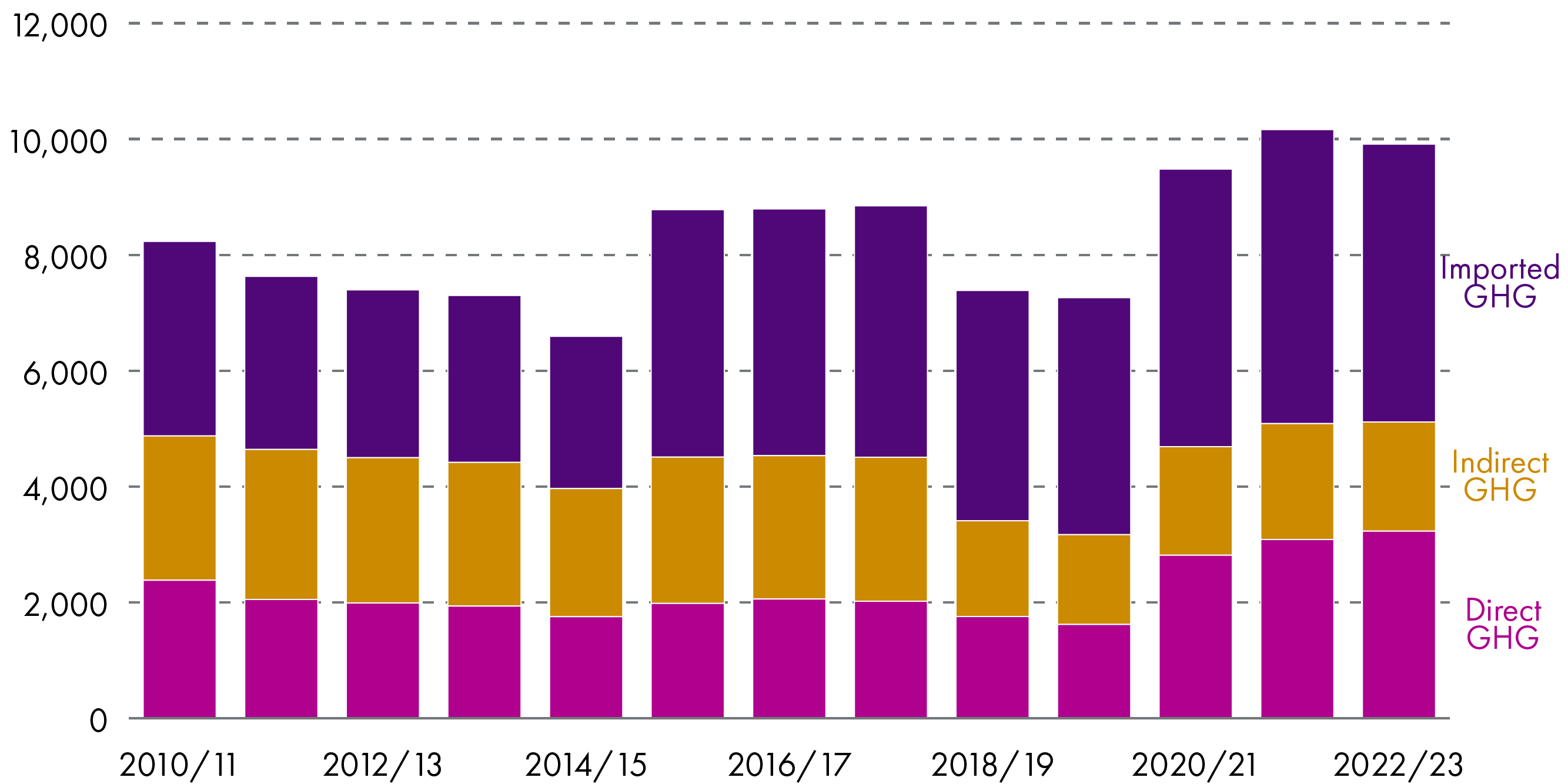

Carbon Assessment of the Scottish Budget

The Climate Change Act 2009 requires the Scottish Government to provide assessments of the impacts on greenhouse gas emissions of activities funded by its budget. The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) Act 2019also requires a carbon assessment of the Infrastructure Investment Plan. Since 2009, thirteen high-level carbon assessments of the budget have been published using an Environmentally-extended Input-Output (EIO)model to estimate emissions. This model is normally used to understand the flow of money though the economy. However, the environmentally-extended version averages greenhouse gas effects for 98 industry sectors and converts the financial inputs from the budget into expected greenhouse gas outputs. This model shows the direct, indirect and imported emissions associated with the Scottish Budget.

It is estimated that total emissions resulting from the goods and services purchased by the 2022-23 Budget will be 9.9 Mt (million tonnes) CO2-equivalent1. The methodology to calculate these emissions is the same as previous years, but the base year used in the Environmental Input-Output model has been changed from 2015 to 2017. Applying this change to last year’s Carbon Assessment results in a reduction from the published 10.2 MtCO2e to 9.8 MtCO2e. Comparing this revised figure with 2021-22 shows that carbon emissions associated with the Scottish Budget rose 1% for 2022-23.

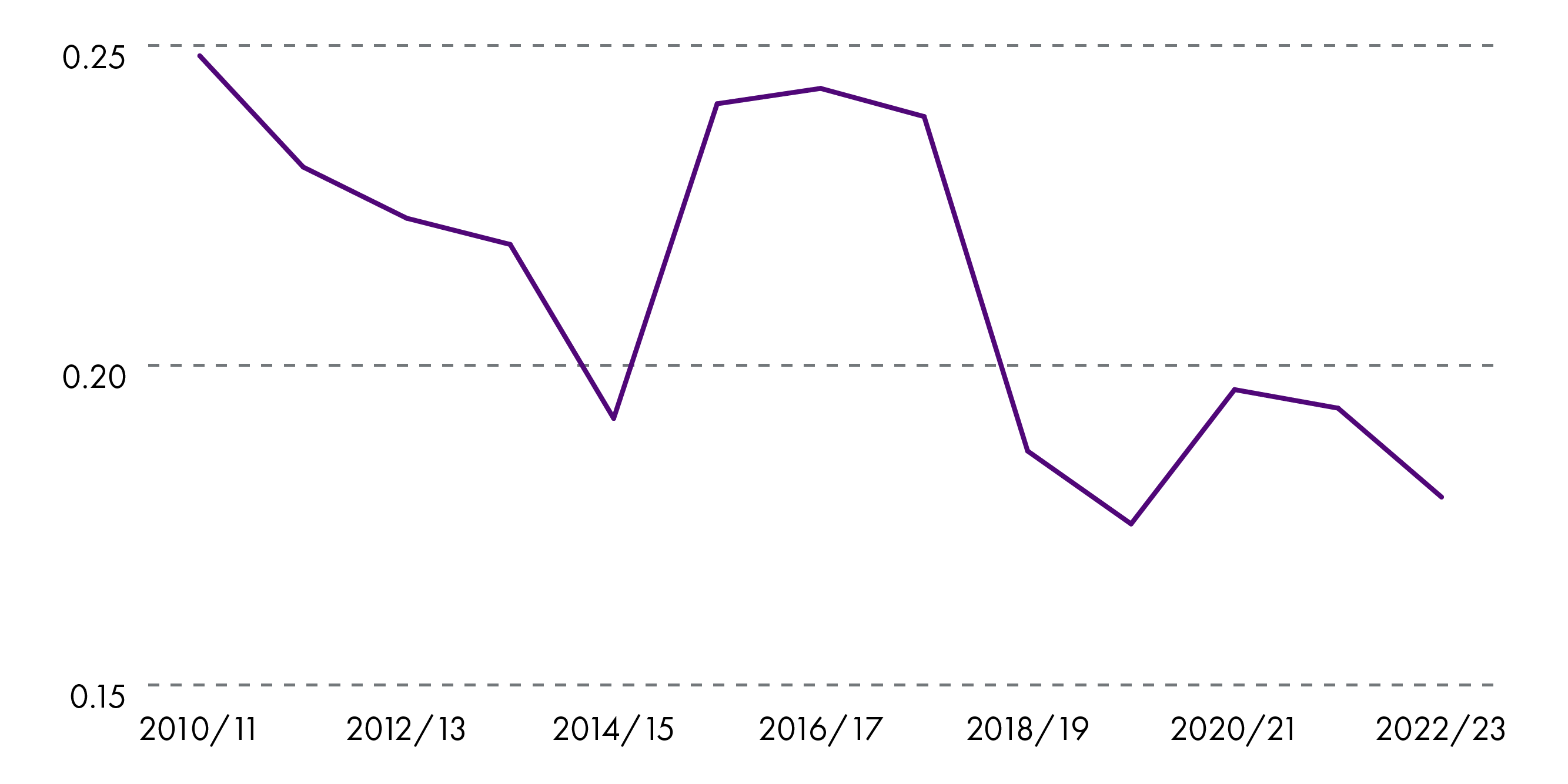

The Scottish Government explains that the increase in emissions is almost entirely down to the corresponding cash growth in total Budget spend over the year, i.e. more spending equals more emissions. To put this into some kind of context, 9.9 MtCO2e is equivalent to 20.7% of the estimated total greenhouse gas emissions for Scotland in 20193. The carbon intensity of the overall budget – that is the ratio of GHG emissions to £ spend, broadly supports the Government’s explanation. Figure 17 below sets out the carbon intensity of the overall Scottish Budget since 2010-11. This chart uses the carbon assessment as published with the draft budget, so does not reflect changes in spending plans as a result of the Parliamentary process or changes to the carbon assessment since its publication. The calculation uses TME excluding non-cash items, and has not been adjusted to remove inflation.

One limitation of this model is that it does not predict the long-term outcome of spending decisions. For example, the emissions associated with the construction of a new railway line are measured. But the effect of the eventual opening of the new line on people’s travel choices is not. So, these assessments help us to understand only the immediate emissions associated with Government spending decisions, and don’t really help to measure whether Scotland is on track to reach “net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. The Scottish Government acknowledge this limitation, and note in the Carbon Assessment that:

“The overall approach to carbon assessment of the budget is under review, in collaboration with Scottish Parliament, and we will seek to incrementally improve it alongside any recommendations from the review.

The aim of this joint review is to improve budget information on climate change – to understand and reduce spend that will 'lock in' future greenhouse gas emissions and increase alignment between the budget and climate change plans.

Recommendations from the review are expected in Summer 2022 with a view to improve budget information on climate for the 2023-24 Budget and subsequent rounds.”

Taxonomy of capital spend

Since 2018-19, the Scottish Government has included a taxonomy of the capital spend in the budget, which sets out the proportion of the spend classified as low, neutral or high carbon. This analysis categorises capital expenditure as either high, broadly neutral or low carbon using a simple methodology.

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 29.1% | 31.8% | 34.9% | 36.9% | 35.0% |

| Neutral | 59.3% | 58.1% | 56.9% | 54.6% | 57.7% |

| High | 11.6% | 10.6% | 8.2% | 8.5% | 7.3% |

In 2022-23, the proportion of capital spending classified as high and low carbon have both reduced. While the amount of spending on low carbon projects has increased by £71 million (3.7%), total capital investment spend has increased by £487 million (9.3%). The amount of spending classified as high fell by £23 million. The Scottish Government notes that some of the spending classified as neutral, such as the Affordable Housing programme and the Health capital programme do include low carbon initiatives, but these were not separately identifiable and so the spend remains classified as neutral in terms of its impact on emissions. The remaining high carbon spend relates to improving and maintain the road network, and funding to help the Highlands and Islands Airports improve links between airports in the region.

Since the taxonomy approach was introduced, the proportion of high carbon spending has fallen from 11.6% to 7.3%, while the proportion of low carbon spending has increased from 29.1% to 35.0%, although as noted above, low carbon spending has reduced slightly from the 2021-22 Budget. In addition to the limitation relating to parts of spending programmes which may be low (or indeed high) but cannot be separately identified, this taxonomy approach does not allow us to assess whether the almost £2 billion in low carbon expenditure offsets the £419 million in high carbon.

As noted above, the Scottish Government state that work is underway to review the budget information relating to climate change, including the taxonomy of capital spend and the carbon assessment.

Replacement of EU funding

This year’s budget sees some conspicuously blank spaces where there have previously been some significant numbers, specifically in relation to the European Regional Development Fund, and the European Structural funds (for example see tables 6.12 and 6.13).

As this SPICe blog explains, EU Structural Funds have been a significant contributor to local and regional economic development in Scotland for the last 40 years. But now the UK has left the EU, it will receive no funding under the European Union’s new financial framework (running from 2021 to 2027).

The UK government for its part has said that it will “ramp up funding”, to “at least match current EU receipts”, calculated by the UK government as meaning, on average reaching around of £1.5 billion a year across the whole of the UK.

The Scottish Government has done its own calculation as to how much Scotland should receive. Adding in replacement funding for the European Territorial Cooperation and LEADER programmes, they calculate this “full amount” as being at least £183 million per year, equating to a 7-year replacement programme of around £1.3 billion for Scotland.

Furthermore the Scottish Government previously produced its own proposals for a Scottish replacement for the EU structural funds1which included the Scottish Government playing a key management role. However, the UK government has taken an increasingly active, and direct, role in economic development in Scotland, for example through

The Community renewal fund (the one-year precursor to the Shared Prosperity Fund) in November 2021, it was announced that Scotland received funding2 for projects valued at just over £18 million, which accounted for 9% of the overall UK funding allocated.

The Levelling Up Fund - The total value of funds awarded in the first round3 amounted to around £1.7 billion across the UK. Eight projects led by Scottish local authorities received funding, worth just under £172 million (around 10% of the total value of all awards).

It is also worth noting that since 2020-21, both Farm Subsidy direct payments and Fisheries Support are funded by HM Treasury, where previously this funding came from the EU. EU replacement funding to the Scottish Government is ring-fenced for that purpose.

The empty rows in this year’s Scottish Government budget remind us that many questions remain about how the replacements to EU funding will operate and work within a new post-EU landscape.

National Performance Framework

The National Performance Framework1 (NPF) was originally introduced in 2007, and has gone through a number of reforms and revisions since then, the most recent of which was in 2018. The budget document states that:

“The Scottish Budget is underpinned by Scotland’s National Performance Framework. This sets out a vision for a more successful country, where all of Scotland has the opportunity to flourish through increased wellbeing, and sustainable and inclusive economic growth.”

For more information on the NPF and how it can be used for budget scrutiny, please see this SPICe Briefing2. It is expected that the next refresh of the NPF will take place in 2023.

Continuing the approach of the 2021-22 Budget, each portfolio in the 2022-23 Budget includes a table showing the portfolio’s “intended contribution to the national outcomes”, split into “primary” and “secondary” outcomes. This is a useful overview, as far as it goes. But it will not be surprising that the “education and skills” primary outcomes are “education” and “children and young people”. There is no attempt to show how the spending plans set out in the budget contribute to the performance assessment of individual indicators in the NPF. This is possibly unsurprising, given data lags in the indicators, and that this is a budget for the next financial year. And on the other hand, there is also no indication in the Budget that any of the performance assessments of any national indicator have had an impact on any spending decisions.

However, there is some more detail in the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement, and in particular in the Annex, Portfolio Assessment and Update to the Key Risks3. This Annex sets out the Government’s assessment of how spend in each portfolio impacts on equality and socio-economic disadvantage. This analysis will no doubt be of interest to the Equality and Human Rights Committee and others in their year-round budget scrutiny, as explained in our chapter on the EFBS.

However it should be noted that the EFBS is specifically focussed on equalities impacts, whereas the links between the budget and the NPF outcomes/indicators is a distinctive piece of analysis. For example, it is not clear the degree to which the EFBS assesses how the budget affects the performance of national indicators on carbon footprint, or natural capital for example. Overall, by taking a high level overview of the NPF within the budget document, and directing the reader to the EFBS for further detail, there is a danger that the analysis of the links between the NPF and the budget become lost.

Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement

What is the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement?