Fisheries governance after Brexit

This briefing explains how fisheries are governed in Scotland, the UK and in cooperation with international neighbours now that the UK has left the European Union (EU). This is an area that has seen significant developments in recent years, in large part driven by the withdrawal of the UK from the EU.

Summary

This briefing explains how fisheries are governed in Scotland, the UK and in cooperation with international neighbours now that the UK has left the EU. It covers the duties and obligations imposed by international fisheries law and policy and how regional cooperation is facilitated through Regional Fisheries Management Organisations and formal negotiations between coastal states.

The briefing then covers frameworks for the governance and management of fisheries within the UK and sets out how fisheries are regulated and governed in Scotland.

A summary of key points is provided at the beginning of each section of the briefing.

About the author

This briefing was written by Professor James Harrison, Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Edinburgh with contributions from SPICe researchers.

Professor Harrison teaches on a number of international law courses, including specialist courses in the international law of the sea, international environmental law, and international law for the protection of the marine environment. His research interests span these areas, considering how the legal rules evolve and interact, as well as examining how international law and policy influences the domestic legal framework.

Key Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Arbitration | A form of dispute settlement in which an independent tribunal (composed of one or more arbitrators) decides the dispute in accordance with the applicable rules of law. The outcome of arbitration is legally binding on the parties and there is not normally any right of appeal at the international level. |

| Bycatch | Unwanted fish and other marine creatures trapped by commercial fishing nets or gear during fishing for a different species. |

| Coastal state | A state with a sea-coastline. A coastal state's jurisdiction relates to its own maritime zones, such as the territorial sea, Exclusive Economic Zone or continental shelf. |

| Conciliation | A form of dispute settlement in which an independent body (composed of one or more conciliators) makes recommendations about the equitable settlement of a dispute, taking into account all relevant factors. The outcome of conciliation is not binding on the parties to the dispute. |

| Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) | An area of sea that extends up to 200 nautical miles from the territorial sea baselines of a state, or up to an agreed maritime boundary with neighbouring coastal states. In this zone, the coastal state may exercise sovereign rights over living and non-living marine resources, as well as limited jurisdiction over marine environmental protection and marine scientific research. |

| Flag state | The state in which a sea-going vessel is registered. Flag states have the legal authority and responsibility to enforce regulations upon vessels that are registered under its flag, wherever they are in the world. |

| High seas | Any area of ocean, seas and marine waters outside of the jurisdiction of a coastal state. |

| Independent Coastal State | The term ‘independent coastal state’ has been widely adopted to describe the UK's new status outside of the European Union. Prior to EU-Exit, the UK was not only required to abide by rules of membership of the EU, including adherence to the Common Fisheries Policy, but the EU also exercised exclusive external competence over fisheries, meaning that it was the EU institutions, rather than the UK as an independent state, that were involved in the negotiation of relevant international rules. Moreover, it was the EU that decided to which rules it would consent to be bound. Now that the UK has left the EU, the UK is able to fully participate in all relevant international institutions concerned with fisheries conservation and management and it is able to choose to which international agreements it becomes a party. |

| Internal waters | The waters within the baselines of a coastal state, which are subject to the full jurisdiction and control of the state. |

| Marine Protected Area (MPA) | A geographically defined area of sea or seabed subject to special protection, often on account of a particular species or habitat that is found there. MPAs are normally regulated or managed in order to achieve specific conservation objectives relating to their protected features. Some activities may still be permitted in MPAs, provided that they do not pose a threat to the species or habitats for which the area has been designated. |

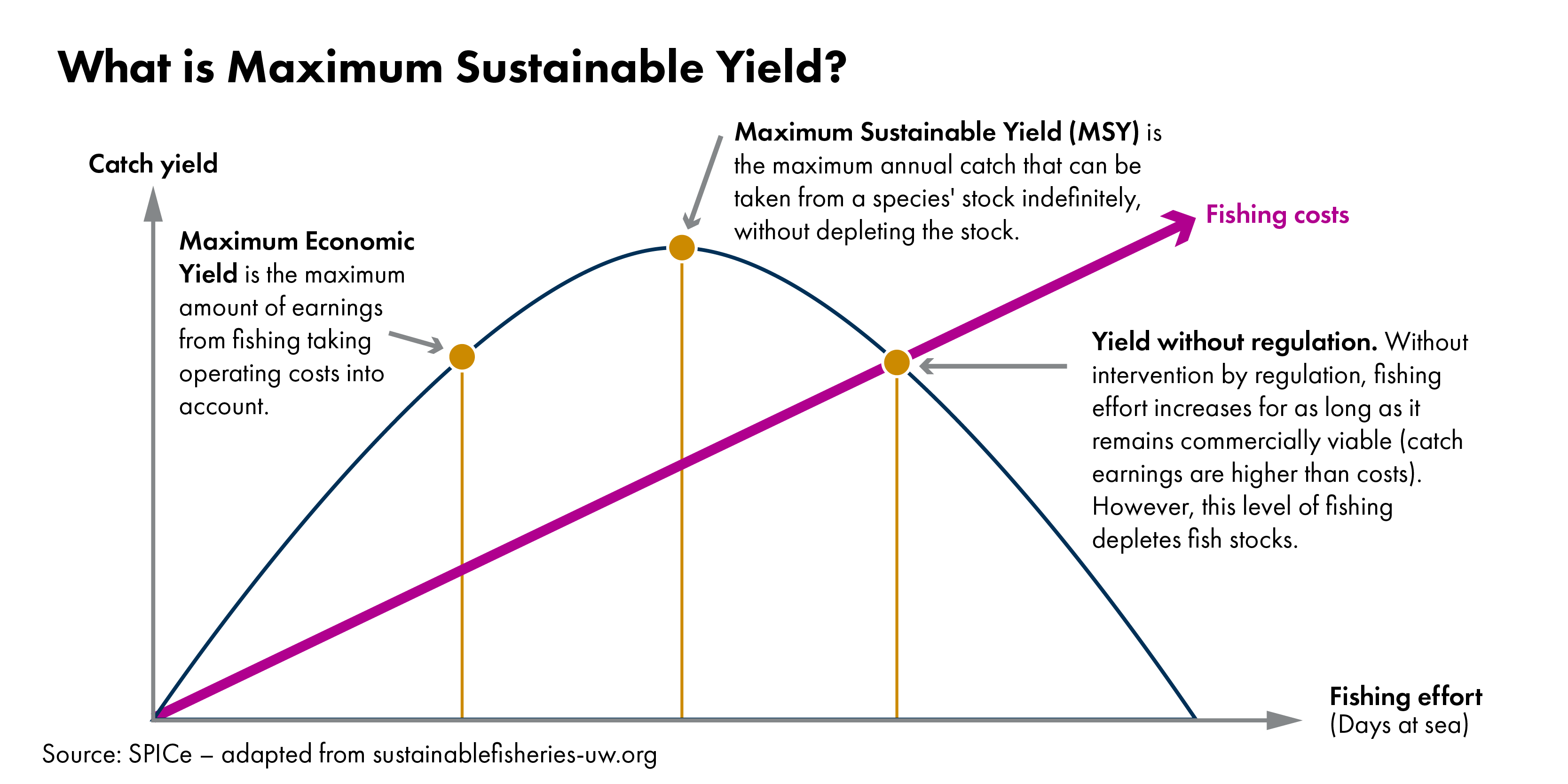

| Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) | MSY is the largest average catch or yield that can continuously be taken from a stock under existing environmental conditions without seriously affecting the reproduction process. |

| Nautical Mile | The standard unit of measurement for distance at sea. One nautical mile is equivalent to 1.1508 miles or 1.852 kilometres. The derived unit of speed is the knot, which equates to one nautical mile per hour. |

| Producer Organisation (PO) | A body formed by fishing vessel owners for the purpose of collectively managing the activities of their members, including the management of quota allocated to member vessels and the marketing of fish products caught by their members. The establishment and operations of POs are governed by retained EU law in Regulation (EU) No 1379/2013 and related guidance. POs are overseen by the relevant fisheries administration in order to ensure that they meet the applicable regulations. There are currently ten POs recognised by Marine Scotland. |

| Quota | The amount of fish, usually expressed in weight, which may be lawfully caught. Quotas may be allocated at the international level to a particular state or at the national level to an individual fishing vessel. |

| Relative stability | Total Allowable Catches (TACs) are shared between EU countries in the form of national quotas. For each stock, a different allocation percentage per EU country is applied for the sharing out of the quotas. This fixed percentage is known as the relative stability key and is based on historical fishing patterns in a reference period from 1973 - 1978. |

| Retained EU Law | A snapshot of the EU law which was in place in the UK at 11pm on 31 December 2020. That was the time at which EU law ceased to apply in the UK. Retained EU law was created so that there was no gap in the law which applied in the UK immediately prior to and immediately after EU law stopped applying. Some parts of retained EU law needed to be changed to ensure the law was clear and could work properly in domestic law, for example, by removing references to the UK being a Member State, removing references to “euros” or replacing a reference to an EU institution with a reference to a UK or Scottish institution. This exercise of changing retained EU law to make sure that it worked properly in domestic law is known as deficiency correction. |

| Territorial sea | An area of sea that extends up to 12 nautical miles from baselines around the coast of a state. In this zone, the coastal state has sovereignty and it may regulate most maritime activities, including fishing. |

| Total Allowable Catch (TAC) | Catch limits (expressed in tonnes or numbers) that are set for many commercial fish stocks. |

| Treaty | A legally binding international instrument, often with the title of a ‘convention’ or an ‘agreement’. Treaties are only binding on those states or other international actors which have consented to be bound, after which they are referred to as ‘contracting parties’ or simply ‘parties’ to the treaty. |

| Zonal attachment | The principle that fishing opportunities should be allocated based upon the temporal-spatial distribution of fish stocks (including, but not necessarily exclusively, where they are caught), rather than on the basis of historical catches by vessels from a particular country. |

1. Introduction

Regulation of the fishing industry is largely devolved to the Scottish institutions. However, the exercise of powers by the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government take place within a broader framework of United Kingdom (UK), regional and international institutions, laws and policies. The purpose of this briefing is to explain how fisheries is governed in Scotland, the UK and in cooperation with international neighbours. This is an area that has seen significant developments in recent years, in large part driven by the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union (EU).

When the UK became an independent coastal state, it was required to forge new relationships with other fisheries actors, such as the EU, Norway, and the Faroe Islands. In particular, the UK has negotiated a new Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU, which has had significant implications for fishing activity at sea and trade in seafood products.

The actions of the UK in the context of fisheries management are also constrained by broader international legal commitments relating to fisheries and the protection of the marine environment. Before leaving the EU, the UK was already bound by international treaties which set out the rights and obligations of states at sea, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the United Nations Agreement on Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks. It has also become a party to a number of other important treaties relating to fisheries management since it left the EU and it will now have to implement these treaty commitments as it develops its post-EU Exit fisheries policy.

In addition to the evolving international framework resulting from EU Exit, the devolution settlement within the UK has also changed. In the field of fisheries, the Scottish institutions have gained significant new powers which were previously exercised by the EU. At the same time, these powers are subject to a new UK-wide legislative framework to replace the EU-wide Common Fisheries Policy, in the form of the UK Fisheries Act 2020, which has knock-on effects for the relationship between the Scottish Government and the UK Government.

2. International fisheries law and policy

Summary

Many individual fish stocks cross international boundaries, therefore there is often a need for international cooperation in the management of fisheries.

International law imposes a number of obligations on states to cooperate in the taking of conservation and management measures in order to avoid the overexploitation of fish stocks. The main treaties in this respect are the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement, both of which lay down general obligations on states to conserve and manage fish stocks through international cooperation.

These global treaties are supplemented by more specific regional and bilateral agreements, which provide for detailed regulation of particular fish stocks. Since the UK became an independent coastal state upon leaving the EU, it has become a party to several regional treaties concerning the conservation and management of fish stocks. It has also negotiated a number of bilateral agreements with its neighbours, which foresee the joint management of shared fish stocks on an ongoing basis.

The most important instrument for these purposes is the Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the UK and the EU, which sets the framework for annual fisheries consultations between the two parties. Such consultations will cover several matters, including:

the setting of Total Allowable Catches (TACs) for shared fish stocks

granting fishing vessels access to each other's waters

the imposition of other technical measures for the conservation of fish stocks and related matters.

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement also addresses trade in seafood products between the UK and the EU. The UK has also concluded more basic arrangements with Norway, the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland.

The practical application of these instruments through annual consultations will have important implications for the type and amount of fish that the Scottish fishing industry will be able to catch.

a. Global fisheries treaties and instruments

i. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the principal global treaty dealing with the rights and obligations of states at sea. The United Kingdom became a party to UNCLOS in 1997. UNCLOS explains, among other things, the extent to which a state may exercise control over the waters around its land territory, as well as its obligations when doing so.

UNCLOS grants sovereignty to a coastal state over the territorial sea, an area of sea up to 12 nautical miles from baselines around its coast. The coastal state can exercise full control over fishing in this area, subject to any other treaty obligations expressly entered into by the coastal state that might affect these rights. A coastal state also enjoys full control over fishing within territorial sea baselines, an area known as internal waters.

UNCLOS also grants so-called ‘sovereign rights’ to the coastal state over the management of marine living resources in a much larger area of sea, known as the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends up to 200 nautical miles from the territorial sea baselines.

For fish stocks that exist solely within its EEZ, a coastal state has exclusive rights over the conservation and management of those resources. This means that it may decide upon the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) of a stock, as well as other conservation and management measures that apply to that stock. In doing so, the coastal state must take into account ‘the best scientific evidence available to it’ and its conservation measures must be designed to ‘maintain or restore populations of harvested species at levels which can produce the maximum sustainable yield, as qualified by relevant environmental and economic factors’ (UNCLOS, Article 61).

Conservation and management measures should also take into account ‘the interdependence of stocks’ and ‘the effects [of fishing] on species associated with or dependent upon harvested species’ (UNCLOS, Article 61), meaning that states should adopt a broad ecosystem approach to fisheries management.

Within these parameters, coastal states have some discretion in setting the TAC and associated conservation and management measures. Indeed, disputes relating to the exercise of sovereign rights over fish stocks within the EEZ are excluded from the system of compulsory dispute settlement under the Convention but may be submitted instead to conciliation (UNCLOS, Article 297).

Maximum Sustainable Yield

Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) refers to the largest average catch or yield that can continuously be taken from a stock under existing environmental conditions. In the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals, states agreed to:

effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics.

The target date for this goal was 2020, but the latest FAO Report of the State of the World’s Fisheries suggests that ‘the fraction of fish stocks that are within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90 per cent in 1974 to 65.8 per cent in 2017.’

Looking at the picture from a regional perspective reveals that North-East Atlantic fisheries have fared somewhat better, but still more than 20% of fish stocks in this region are fished at unsustainable levels, meaning that further action is required to ensure sustainable fishing. The Fisheries Act 2020 (see below) incorporates MSY as part of the 'precautionary objective'.

Where fish stocks cross the boundary of two or more states, the relevant coastal states are also under an obligation to ‘seek to agree’ upon appropriate management measures ‘either directly or through appropriate subregional or regional organizations.’ (UNCLOS, Article 63; see also Article 64).1

If states cannot agree on conservation and management measures, a coastal state may still unilaterally set a TAC for areas under its jurisdiction, provided that it complies with its obligation to ensure that the stocks are maintained or restored to MSY levels.

The coastal state is also under an obligation to promote the optimum utilisation of fish stocks within its EEZ, meaning that if its own fishing fleet cannot catch the entire TAC, it must grant access to other states to allow them to catch any surplus (UNCLOS, Article 62). Whilst these provisions are expressed as obligations for the coastal state, UNCLOS recognises that coastal states have a significant amount of discretion in determining the size of any surplus and in deciding how to allocate that surplus to other states. A coastal state may also use its discretion to extend access of foreign fishing vessels to the territorial sea (within 12 nautical miles).

In all circumstances, the coastal state may set conditions on access, meaning that foreign vessels will have to comply with any conservation and management measures set by the coastal state. As a matter of international law, the coastal state can enforce measures against any foreign fishing vessel fishing within its EEZ, territorial sea, or internal waters. Its enforcement powers include the right to board, inspect, arrest and prosecute a vessel (and its crew) suspected of violating national fisheries regulations.

Waters beyond the territorial sea and the EEZ are known as the ‘high seas’ and any state can fish in this area provided that they meet their international obligations, including the duty to cooperate with other states to adopt measures necessary for the conservation of marine living resources (UNCLOS, Article 117-119). Such cooperation often takes places through Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) (see below).

ii. United Nations Agreement on Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks

International cooperation is particularly important for those fish stocks which straddle the waters of one or more coastal state as well as the high seas (UNCLOS Article 63(2)) or stocks which are classified as highly migratory (UNCLOS, Article 64 and Annex I). The need for international cooperation in managing these types of fish stocks is further reinforced by what is known as the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA). 1

Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks

A straddling fish stock is one which occurs both within the EEZ of one or more states and in an area on the high seas beyond and adjacent to that zone. Examples in the North-East Atlantic include mackerel, blue whiting, Norwegian spring spawning herring and Rockall haddock.

A highly migratory fish stock is a stock of a species listed in Annex I of UNCLOS, which includes tunas, marlins, sail-fishes, swordfishes, sauries, and oceanic sharks. Typically, these stocks move both through the EEZ of a number of states and through the high seas.

The UK has been a party to the UNFSA since December 2001. The UNFSA encourages states to establish Regional Fisheries Management Organisations as a forum in which states agree on and monitor compliance with conservation and management measures for straddling and highly migratory fish stocks (see below).

The UNFSA also requires states individually and jointly to promote the long-term sustainability of shared fish stocks and to:

apply a precautionary approach widely to the conservation, management and exploitation of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks in order to protect the living marine resources and preserve the marine environment.

(UNFSA, Article 6(1)).

In particular, states are encouraged to adopt precautionary ‘reference points’, which will indicate when management measures are required to limit fishing of specific stocks within safe biological limits. These reference points are statistical thresholds based on independent scientific assessments of fish stock health and population.

iii. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) is a global intergovernmental organisation for cooperation on matters relating to food, agriculture and fisheries. It is based in Rome, Italy, and it has 194 Member States (including the UK), one Member Organisation (the EU), and two Associate Members (Faroe Islands and Tokelau). The FAO has developed a number of binding and non-binding instruments relating to fisheries conservation and management.

FAO Treaties:

2009 Agreement on Port State Measures to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (the UK became a party on 31 January 2021)

1994 Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas (the UK became a party on 1 January 2021)

FAO voluntary instruments and mechanisms

b. Regional cooperation on fisheries

i. Introduction

Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) provide a forum for states within a particular region – such as the North-East Atlantic – to discuss the current status of relevant fish stocks and to adopt conservation and management measures. These measures normally become binding on members if they do not object within a prescribed period.

Both the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) identify RFMOs as the principal means of developing agreed conservation and management measures for straddling and highly migratory fish stocks. The UNFSA prescribes that:

only those States which are members of [a RFMO] or which agree to apply the conservation and management measures established by such organization or arrangement, shall have access to the fishery resources to which those measures apply.

(Article 8(4)).

Prior to EU Exit, the UK’s interests were represented at relevant RFMO meetings by the EU. Since becoming an independent coastal state, the UK has become a member of a number of relevant RFMOs.

ii. North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission

The United Kingdom became a member of the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) as of 7 October 2020, joining Denmark (in respect of the Faroe Islands and Greenland), the EU, Iceland, Norway and the Russian Federation. The objective of NEAFC is:

To ensure the long-term conservation and optimum utilisation of the fishery resources in the Convention Area, providing sustainable economic, environmental and social benefits.1

The Commission is given powers to adopt conservation and management measures concerning fisheries, including, but not limited to, the regulation of fishing gear, closed seasons, closed areas, the establishment of TACs, the regulation of fishing effort, and the enforcement of conservation and management measures.

The mandate of NEAFC covers most marine living resources in the North-East Atlantic with the exception of tunas and tuna-like species and salmon, both of which have their own special regimes, discussed below. In particular, NEAFC regulates several straddling stocks, namely mackerel, blue whiting, Norwegian spring spawning herring, and Rockall haddock. Whilst the NEAFC Convention Area covers waters within and beyond national jurisdiction in the North-East Atlantic, NEAFC may only apply conservation and management measures to waters within national jurisdiction with the express consent of the coastal states concerned.

In practice, NEAFC recommendations tend to focus on fishing that takes place on the high seas, leaving coastal states to determine appropriate measures for fishing that takes place within national jurisdiction. Direct consultations on management measures for widely distributed species such as mackerel, blue whiting and Norwegian spring spawning herring take place between relevant coastal states on an annual basis prior to discussions taking place at NEAFC. The UK joined these coastal state consultations for the first time in 2020. The initial allocation of quota to the UK for these stocks was agreed with the EU as part of the negotiation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (see below).

Case Study - Mackerel

Mackerel is by far the most valuable species fished by the Scottish fleet. In 2019, Scottish fishing vessels landed 170,744 tonnes of mackerel at a market value of £180,893,000.2 Mackerel is a widely distributed stock that is fished throughout the North-East Atlantic. As a result, the management of the stock is subject to consultations between all relevant fisheries actors, namely Norway, the EU, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom. Consultations are also often attended by the Russian Federation as an interested observer given its participation in fishing for mackerel on the high seas. Based upon these coastal state consultations, NEAFC adopts conservation and management measures for mackerel fishing on the high seas.

Until recently, Norway, the EU and the Faroe Islands had agreed a multi-year management plan for mackerel in which they agreed on a division of the overall TAC, initially for the period 2014-2018 and later extended until 2020. Iceland and Greenland, however, refused to join this arrangement and they continued to set unilateral quotas. The Russian Federation also augmented its fishing effort on the high seas. As a result, pressure on the mackerel stock increased, leading to fishing at levels far in excess of the scientific advice.

In January 2019, the Marine Stewardship Council announced that it would be suspending its MSC sustainability certification of all North-East Atlantic mackerel fisheries.3 This is a matter on which the Scottish Government has expressed concern, with Fergus Ewing, then Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy and Tourism, saying to the Scottish Parliament on 4 December 2019 that ‘in the absence of full-party agreements for pelagic stocks [stocks found in the ‘pelagic zone’ of the ocean, such as mackerel], uncontrolled fishing in international waters is the biggest risk of unsustainable fishing.’

At the consultations held in December 2020, the relevant coastal states agreed on a TAC of 852 284 tonnes based on scientific advice and they committed to ‘revert to the issue of a sharing arrangement for Mackerel in the North-East Atlantic in early 2021.’4 Similarly NEAFC recommended that catches should not exceed 852 284 tonnes but it merely called for contracting parties to establish their own catch limits. No further progress was made on agreeing an allocation of the TAC and in June 2021, both Norway and the Faroe Islands announced significant unilateral increases in their mackerel quotas. This was condemned as "reckless and irresponsible” by UK and EU fishing interests.5

The North Atlantic Pelagic Advisory Group (NAPA), a consortium of processors, buyers and retailers, has also called for urgent action and threatened to re-evaluate their sourcing pollution if the current unsustainable situation continues. NAPA launched a fisheries improvement project in April 2021 to drive change in the fishery.

In September 2021, ICES (see below) issued its latest advice on mackerel, indicating that the spawning stock biomass had continued to decrease and it advised a further reduction in catch for 2022.

For more detail on the background to the mackerel dispute, see the SPICe briefing on Mackerel.

iii. International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas

The UK became a member of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas(ICCAT) on 21 October 2020. ICCAT is concerned with the conservation and management of tunas and other tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean. It has the power to adopt conservation and management measures that are applicable to fishing for relevant stocks, wherever they are located, within or beyond national jurisdiction. The principal species of interest to the UK is the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, for which it has a small quota as a result of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU (see below).

Atlantic bluefin tuna has been the subject of significant efforts to rebuild depleted stocks, but the species is still classified as near threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Commercial fishing for Atlantic bluefin tuna is currently prohibited in UK waters, although tag and release schemes are underway to gather further information about the stock.12

iv. North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation

The UK became a member of the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation (NASCO) on 27 November 2020. Fishing for salmon on the high seas is prohibited under the terms of the Convention for the Conservation of Salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean and the principal function of NASCO is therefore to provide a forum for coastal states to exchange information and cooperate on the conservation and management of salmon fisheries within national jurisdiction and related matters.

Under the so-called ‘Williamsburg Resolution’ adopted in 2003, NASCO has also developed a work programme relating to the introduction of non-indigenous fish, transgenics (genetic modification) and the impacts of aquaculture on wild salmon stocks. NASCO Members are expected to develop national action plans to address these issues and they are subject to review by an independent panel convened by NACSO.

v. International Council for the Exploration of the Seas

Another important intergovernmental organisation underpinning these other regional arrangements is the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES), which promotes marine research, with a particular focus on sea fisheries. On request, ICES may provide independent scientific information and advice to national governments or other international organisations, including NEAFC and NASCO.

It is normally ICES that provides the initial scientific assessments which are the basis for setting the TAC of fish stocks in UK/Scottish waters. Whilst states are expected to ‘take into account the best scientific evidence available to it’ when adopting conservation and management measures (UNCLOS, Article 61), states are not legally obliged to implement all scientific recommendations from ICES.

vi. OSPAR Commission

The Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, also known as the ‘OSPAR Convention’, also has implications for fisheries management. The OSPAR Commission established under this Convention does not have a mandate to adopt fisheries management measures, but it does promote the conservation of marine species and habitats more generally.

The List of Threatened and/or Declining Species adopted by the OSPAR Commission includes a number of fish species found in UK/Scottish waters, including Angel Shark, Basking Shark, Bluefin Tuna, Cod, Common Skate, Gulper Shark, Leafscale Gulper Shark, Orange Roughy, Portuguese Dogfish, Atlantic Salmon, Spurdog, and Thornback Ray. For each of these species, contracting parties are expected to take appropriate conservation measures, including the potential designation of Marine Protected Areas.

Given the implications for fisheries management, the OSPAR Commission has worked closely with NEAFC to coordinate their actions to protect and preserve the marine environment of the North East Atlantic, including through the so-called ‘Collective Arrangement regarding selected areas beyond national jurisdiction in the North-East Atlantic’.

c. UK bilateral fisheries relations

i. Fisheries relations with the EU

The EU is undoubtedly the most important fisheries partner for the United Kingdom, with a large number of fish stocks shared between the two parties. The new rules for fisheries relations between the EU and the UK are found in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which was concluded at the end of 2020 and entered into force on 1 May 2021. The Agreement addresses various aspects of fisheries cooperation and it provides a framework for future negotiations between the UK and the EU on fisheries matters.

Regulatory cooperation

The TCA begins by confirming that the UK and the EU (on behalf of its Member States) possess sovereign rights for the conservation and management of marine living resources under their respective jurisdictions, but it goes on to commit the two parties to cooperating:

with a view to ensuring that fishing activities for shared stocks in their waters are environmentally sustainable in the long term and contribute to achieving economic and social benefits.

(TCA, Article 494).

In this respect, the Parties agree to have regard to a number of objectives and principles in the exercise of their sovereign rights (TCA, Article 494). In addition to these general objectives and principles, the parties have also agreed to comply with various international agreements and other instruments relating to the conservation and management of fish stocks, including:

the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement

the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) Compliance Agreement

the FAO Port State Measures Agreement

the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

measures adopted by relevant Regional Fisheries Management Organisations. (TCA, Article 404).

In addition, the parties have agreed to:

adopt and maintain their respective effective tools to combat IUU [Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated] fishing , including measures to exclude the products of IUU fishing from trade flows, and to cooperate to that end.

(Article 404).

Each party remains responsible, in principle, for developing technical measures (such as restrictions on the use of particular fishing gear in specific situations or areas, closed areas, or minimum fish landing sizes) for areas under its own jurisdiction, provided that such measures are based on the ‘best available scientific evidence’ and that the same measures are applied to its own vessels and the vessels of the other party. (TCA,Article 496(2)).

In other words, when adopting conservation and management measures within its national jurisdiction, the UK must apply the same measures to vessels flying the flag of an EU Member State as it does to its own vessels. As a matter of procedure, a party must notify the other party of any proposed technical measures ‘allowing sufficient time for the other Party to provide comments or seek clarification.’ (TCA, Article 496(3)). This provision leaves some ambiguity over the precise period that is required for notifications, which may lead to disputes about whether or not sufficient time is given.

Fishing Opportunities

The negotiation of fishing opportunities (i.e. quotas and days at sea) is one of the main issues addressed in the fisheries chapter of the TCA. The Agreement establishes a detailed procedure for the negotiation of Total Allowable Catches (TACs) for shared stocks, as well as rules setting out what happens if the parties cannot agree. Consultations should take place on an annual basis to agree TACs, as well as other conservation measures that the parties consider to be necessary.

By 31 January of any year, the parties are to set the schedule for consultations with the aim of agreeing TACs for the stocks listed in Annex 1 of the TCA by 10 December. The schedule must consider the provision of scientific advice by ICES (see above) which usually occurs over the summer months. The schedule will also need to consider parallel negotiations with other relevant coastal states for widely distributed stocks. If the parties have not reached an agreement by 10 December, the TCA commits them to ‘immediately resume consultations … with a view to exploring all possible options for reaching agreement in the shortest possible time.’ (Article 499(1)). If agreement is still not forthcoming by 20 December, the parties must unilaterally set a ‘provisional TAC corresponding to the level advised by ICES, applying from 1 January.’ (Article 499(2)).

In other words, the scientific advice becomes the baseline for provisional TACs in the absence of agreement. The only exceptions to this rule are for so-called ‘special stocks’ for which provisional TACs may be set unilaterally by each party based on guidelines to be adopted by the Specialised Committee on Fisheries (an EU-UK governance committee established under the TCA). Special stocks include stocks where ICES advice is for a zero TAC, stocks caught in a mixed fishery consisting of a variety of fish species where one of the stocks is vulnerable, and any other stock agreed by the parties to require a special approach. To minimise the setting of unilateral TACs for special stocks, the parties have agreed to prioritise negotiations on special stocks early in the consultation cycle.

Once the overall TAC has been agreed, the share of the TAC between the two parties will be determined in accordance with the percentage share allocated to each party for each stock as set out in Annex 35 of the TCA. This was one of the issues that divided the parties during the negotiations. The EU had argued that the distribution of TACs should be based upon historical fishing patterns, in line with the principle of ‘relative stability’ under the Common Fisheries Policy. In other words, the EU was seeking to retain the status quo in terms of fishing opportunities.

In contrast, the UK had insisted that TACs should be divided in accordance with the principle of zonal attachment, meaning that fishing opportunities should be allocated based upon the volume and geographic location of fish stocks within a given period of time. This approach would have given the UK a greater share of the TAC for many fish stocks compared to the position under relative stability.1

The result of the negotiations is a compromise between these two positions. The two parties ultimately agreed upon a transitional arrangement, whereby the UK share of the TAC would gradually increase from the levels previously applied under the Common Fisheries Policy over a six-year period.

Annex 35 contains a list of shared stocks and it specifies the percentage of the TAC that shall be shared between the EU and the UK in 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026 onwards. TACs in place at the end of this period would continue to apply beyond 2026 unless the parties agree otherwise. Annex 36 also includes a split of quota relating to stocks shared with Norway, stocks managed through coastal state consultations, and stocks managed by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations. This Annex also deals with TACs for species found within the waters of a single party, but to which the other party has access rights under the TCA.

Whilst the TCA introduces an up-lift of approximately 25% (based upon value of the relevant stocks) over the six-year period, the precise increase varies between fish stocks. It was calculated in a recent report from the Marine Management Organisation that the new arrangement represents a ‘mean value increase to the UK fleet of £143.9 million a year.’2 However, the deal has been criticised by industry as failing to meet expectations. According to Elspeth MacDonald, chief executive of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation, the deal falls ‘very far short of the government’s stated aim of achieving zonal attachment.’3

Indeed, analysis produced on behalf of the National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations suggested that the industry could expect to incur losses of £64 million or more per year and emphasized that many of the species for which a quota uplift had been gained are not fished by the UK fleet.4

The Scottish Government also criticised the deal and it published an analysis on 29 December 2020 in which it claimed ‘the Brexit fisheries deal negotiated by the UK Government will mean a fall in the quantity of key fishing stocks landed by the Scottish fleet’, although it recognised that the situation was better for some stocks (e.g. pelagic stocks) compared to others (e.g. cod and saithe).5

The first annual fisheries consultations between the UK and the EU began in early 2021 and they concluded, after several delays in June 2021, when TACs were agreed for 70 shared stocks. According to media reports, the agreed TACs largely follow the TACs that had been provisionally set by each side in the talks, apart from eight stocks where the final TAC saw a small increase.6

The agreement was welcomed in many quarters as a positive sign of EU-UK cooperation, although some environmental groups criticised the two sides for failing to follow scientific advice on all of the relevant stocks. For example, Oceana pointed out that the EU and UK had set quotas above scientific advice in relation to cod in the West of Scotland and whiting in the Irish Sea.7 In both of these cases, ICES had recommended a zero-catch limit, but the EU and the UK agreed a by-catch quota, therefore allowing vessels to catch these fish when fishing for other species, although targeted fishing for these stocks is prohibited.

As TACs are agreed between the parties, they cannot be unilaterally altered. Therefore, if a party wishes to amend the TAC or the distribution of shares, it must request consultations to that end. (Article 498(5)). This mechanism would apply if the UK wished to negotiate greater quota shares at the end of the transitional period in 2026. However, there are other flexibility mechanisms that are available to states to manage their quotas, discussed in the following section.

Quota flexibility and quota swaps

It is normal practice in fisheries negotiations to allow some flexibility in managing quota across different fishing seasons, applying to both under-utilisation and over-utilisation of quotas. A party may transfer unused allocations of up to 10% to the following year, so-called ‘quota-banking’. In addition, a party may authorise fishing by vessels of up to 10% beyond its quota of a particular TAC provided that that those quantities will be deducted from the party’s quota for the following year. The results of the first UK-EU annual negotiations confirm that such arrangements continue to apply to TACs agreed under the TCA.

In addition, the TCA makes provision for ‘a mechanism for voluntary in-year transfers of fishing opportunities between the Parties, to take place each year’ – known as ‘quota swaps’ - to be agreed through the Specialised Committee on Fisheries (Article 498(8)). The fishing industry had expressed concerns about these provisions, which they feared would not permit swaps to be made as efficiently as under the previous rules, whereby Producer Organisations were able to agree swaps directly subject to final sign-off from governments.8

During the 2021 consultations between the EU and the UK, the two delegations ‘noted the importance of transfers of fishing opportunities’ which were ‘necessary for operational needs’ and they committed to ‘establishing all of the necessary legal and procedural arrangements to enable such transfers between the Parties.’ In the meantime, they also agreed to ‘develop and arrange an interim basis for these transfers immediately.’9

At the end of June 2021, Mike Park, chief executive of the Scottish White Fish Producers’ Association, was reported as saying that there would be some quota exchanges this year ‘but not to the extent that [Producer Organisations] would have been able to arrange with their EU counterparts under the pre-Brexit system’ and he called for the development of a system ‘where the [Producer Organisations] consulted and [governments] mandated the deals.’10 This is a matter that will be addressed by the Specialised Committee on Fisheries set up under the TCA.

Access arrangements

Access to British fishing grounds was a key issue during the negotiation of the TCA. Under the Common Fisheries Policy, EU vessels had full access to fish in the UK EEZ and some EU vessels also had further rights to fish in the territorial sea between 6 and 12 nautical miles based upon historic fishing patterns. During the negotiation of the TCA, the EU was keen to retain existing access to UK waters, whereas the UK wanted to negotiate access on an annual basis.

In a Protocol on Access to Waters (TCA, Annex 438), the final agreement provides for a transitional arrangement which establishes a so-called ‘adjustment period’ from 1 January 2021 to 30 June 2026. During this time, ‘each Party shall grant to the vessels of the other Party full access to its waters’ to fish for quota stocks ‘at a level that is reasonably commensurate with the Parties’ respective shares of the TAC’, as well as access to fish for non-quota stocks ‘at a level that equates to the average tonnage fished by that Party in the waters of the other Party during the period 2012-2016.’ (Annex 438: Protocol on Access to Waters, Article 2).

This means that EU vessels will still have access to fishing grounds in the EEZ adjacent to Scotland, although they will no longer have access to fishing grounds within the territorial sea (to 12 nautical miles) of Scotland. However, in a change from the previous situation, EU vessels are now required by UK law to get a fishing licence to fish in UK waters (see below).

A significant challenge in implementing the new access provision has been the lack of reliable data concerning the landings by EU vessels of non-quota stocks (e.g. crab, lobster and other stocks for which no TAC is set) caught in UK waters. During the 2021 annual consultations, the two parties exceptionally agreed that they would not impose tonnage limits on non-quota stocks in the 2021 fishing year, but rather ‘will closely monitor and exchange landings data’ with a view to ‘developing multi-year strategies for the conservation and management of non-quota stocks via the [Standing Committee on Fisheries].’9

Following the adjustment period, access will be granted at a level and on conditions to be agreed through annual consultations ‘with the objective of ensuring a mutually satisfactory balance between the interests of both Parties.’ (TCA, Article 500). The TCA goes on the say that access shall ‘normally’ result in each party granting access to fish for quota stocks in the EEZ at a level that is reasonably aligned with the Parties’ respective shares of the TACs and access to fish for non-quota stocks in the EEZ at a level ‘that at least equates to the average tonnage fished by that Party in the waters of the other Party during the period 2012-2016.’ (TCA, Article 500(4)). Although this provision does not constrain the discretion of the parties to negotiate a different outcome, it does set an expectation for continued access under similar conditions as set out in the Protocol on Access to Waters.

Failing agreement on access arrangements, it will be for each party to unilaterally notify the other party of what access foreign vessels may have to fish in its waters. However, where the other party is unsatisfied with the level of access that is provided, it may ‘take compensatory measures commensurate to the economic and societal impact of the change in the level and conditions of access to waters’ (TCA, Article 501).

Such compensatory measures may include suspension of access, in whole or part, to fishing in its waters or suspension of the preferential tariff treatment granted to fishery products. Several safeguards are attached to the exercise of this right of retaliation. Firstly, the TCA makes clear that ‘such impact shall be measured on the basis of reliable evidence and not merely on conjecture and remote possibility.’ (TCA, Article 501).

Secondly, the state proposing to take compensatory measures must give at least seven days’ notice of its intention to do so, which provides time for the parties to consult on a mutually agreeable solution. Thirdly, any dispute over the compensatory measures may be submitted to arbitration before an independent tribunal for a binding decision. These safeguards are intended to prevent any party abusing this right to retaliate.

Trade

One of the outcomes of the TCA is that it exempts all goods being exported from the UK into the EU from customs duties. (TCA, Article 21). However, the TCA does not prevent a party from carrying out customs checks, nor does it prohibit a party from applying non-tariff measures to goods originating in the other party, such as sanitary and phytosanitary (disease control) measures to protect human, animal, and plant life or health. In particular export health certificates will be required for each consignment of seafood destined for the EU market. In order to qualify to export fish products to the EU, all Scottish fishing vessels are now also obliged to register as a food business and undergo inspections by the local authority.12

In practice, the additional border checks and other regulatory requirements have caused significant challenges for the seafood industry during the first half of 2021. Figures from the Scottish Government suggest that at the beginning of 2021, consignment sign-off was taking six times longer, the transit of goods to France was taking three days instead of an overnight transit, and additional paperwork and checks had increased costs of £500-600 per consignment.13

After protests about delays and additional paperwork required for exporting seafood under the new rules, the UK Government agreed to establish a £23 million compensation fund (the Seafood Disruption Support Scheme14) and it convened a Scottish Seafood Exports Taskforce in order to explore the options for improving the situation.

The Seafood Disruption Support Scheme was only designed to cover the actual losses incurred by businesses exporting seafood and it had a claims cap of £100,000, which was described as ‘arbitrary’ in a report the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee.15 A further UK Government Seafood Response Fund provided broader support to businesses affected by the downturn of seafood markets due to the coronavirus and/or disruption to exports as a result of EU exit. This was supplementary to the Seafood Producer's Resilience Fundestablished by the Scottish Government in February 2021.16

In order to discuss ways of addressing the challenges facing the seafood industry in the longer term, the Scottish Seafood Exports Taskforce met eight times between February and June 2021, bringing together representatives from the UK and Scottish Governments, as well as expertise from the catching, processing, exporting and aquaculture sectors. The Taskforce produced a final report on 26 August 2021.17

As recognised by the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, ‘the new non-tariff barriers for exporters to the EU will impose substantive and enduring costs’, which may affect the viability of some smaller businesses.15 The UK Government's response, however, pointed to the opportunity for the UK and the EU to cooperate on reducing Sanitary and Phytosanitary controls (SPS) in order to avoid unnecessary trade barriers and this matter will be discussed in the SPS Specialised Committee established under the TCA.15

Specialised Committee on Fisheries

The TCA establishes a Specialised Committee on Fisheries in order to oversee the operation of the fisheries chapter and to ‘provide a forum for discussion and co-operation in relation to sustainable fisheries management.’ (TCA, Article 508). The Committee is composed of representatives of each party. The UK Government has recognised the need to ensure ‘full and proper engagement’ with the devolved administrations on the implementation of the TCA20 and it has committed that ‘the devolved authorities and Crown dependencies will be fully involved in the process.’

The SCF is expected to meet 3 to 5 times annually. The first meeting of the Committee took place on Tuesday 20 July 2021, at which priorities for future work were discussed. 21

Review

The parties to the TCA have committed to reviewing the fisheries chapter four years after the end of the adjustment period, i.e. 2030, with the aim of ‘considering whether arrangements, including in relation to access to waters, can be further codified and strengthened’ (TCA, Article 510).

ii. Fisheries relations with Norway

The UK entered into a fisheries agreement with Norway on 30 September 2020. The UK-Norway Agreement is far simpler than the EU-UK arrangements on fisheries management and does little more than establish a general framework for cooperation between the two countries.

In many ways, the UK-Norway Agreement reflects the provisions of the EU-Norway Agreement, albeit with some subtle differences. The Agreement sets out the principles which will inform cooperation between the two parties, as well as a commitment to hold annual consultations on access and quota transfer.

The Agreement makes specific reference in the preamble to ‘zonal attachment as an important principle of international fisheries management’ although its description as a principle means that it does not commit either party to a particular method of calculating zonal attachment. Rather, the inclusion of zonal attachment in the preamble can probably be best understood as 'a signal to the EU about the UK government's stance' relating to zonal attachment.1

There is no specific provision for joint fisheries management between the UK and Norway, because the stocks in which they are both interested are shared with other states. Therefore, management of North Sea cod, haddock, saithe, whiting, plaice, herring and sprat are addressed in trilateral consultations between the EU, Norway and the UK2, whereas management of mackerel, Norwegian Spring Spawning herring and blue whiting takes place through the wider coastal state consultations (see above). Nevertheless, it is possible that annual consultations between the UK and Norway could address management measures and the preamble to the Agreement does note ‘the advantage of consistency in relation to technical measures on the conduct of fisheries in adjacent waters of the Parties.’

The first round of fisheries consultations in 2021 ended without an agreement between the UK and Norway3, meaning that vessels from one country had no access to the waters of the other country and no quota exchanges could take place during 2021. According to the UK Government, ‘the UK sought to secure fishing opportunities for the UK industry, whilst at the same time addressing the historic imbalance between fishing opportunities taken in UK waters by other coastal states compared to those the UK took in theirs’, but Norway was not ‘willing to provide appropriate compensation for access to fish in UK waters, without which the relationships would have been left significantly weighted against the UK.’4

This result received mixed comments from industry. Lack of access to Norwegian waters has caused significant problems for the UK’s remaining distant water vessels which fish out of the port of Hull. 5 Similarly, the Scottish whitefish fleet predicted difficulties arising from the lack of access to Norwegian waters.6

In contrast, the Scottish pelagic fleet was more positive about the outcome7 and the Shetland Fishermen’s Association also welcomed the outcome, observing that previous deals between Norway and the EU ‘were heavily skewed against the local pelagic and demersal fleets.’8

Consultations will resume again next year, when both sides will have to reflect on whether to renew access arrangements and quota exchanges.

In July 2021, the UK also entered into a free trade agreement with Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, which amongst other things grants tariff reductions on imports of prawns, shrimp and whitefish, including zero tariffs for many fish products.9 The deal was welcomed by some seafood processors, but other parts of the fishing industry were more critical, noting that it comes after the UK had failed to reach an agreement on fisheries access with Norway. In the words of one Scottish MP, ‘at the same time that Norway removed our right to fish for cod in its waters, the UK has given them the right to sell the self-same cod without any tariff at all to UK chippies.’

iii. Fisheries relations with the Faroe Islands

The UK also entered into a fisheries agreement with the Faroe Islands on 29 October 2020, which takes a very similar approach to the UK-Norway Fisheries Agreement.

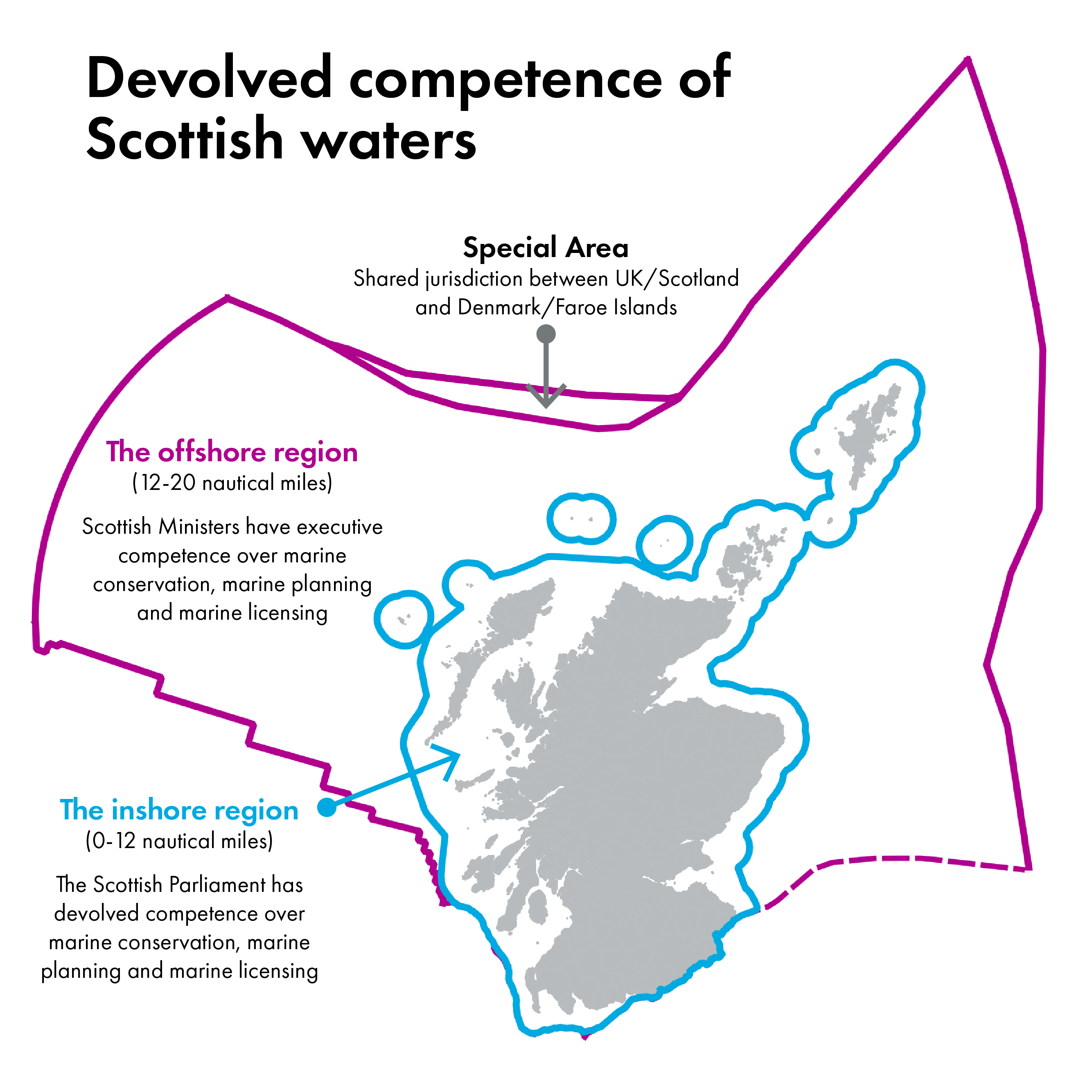

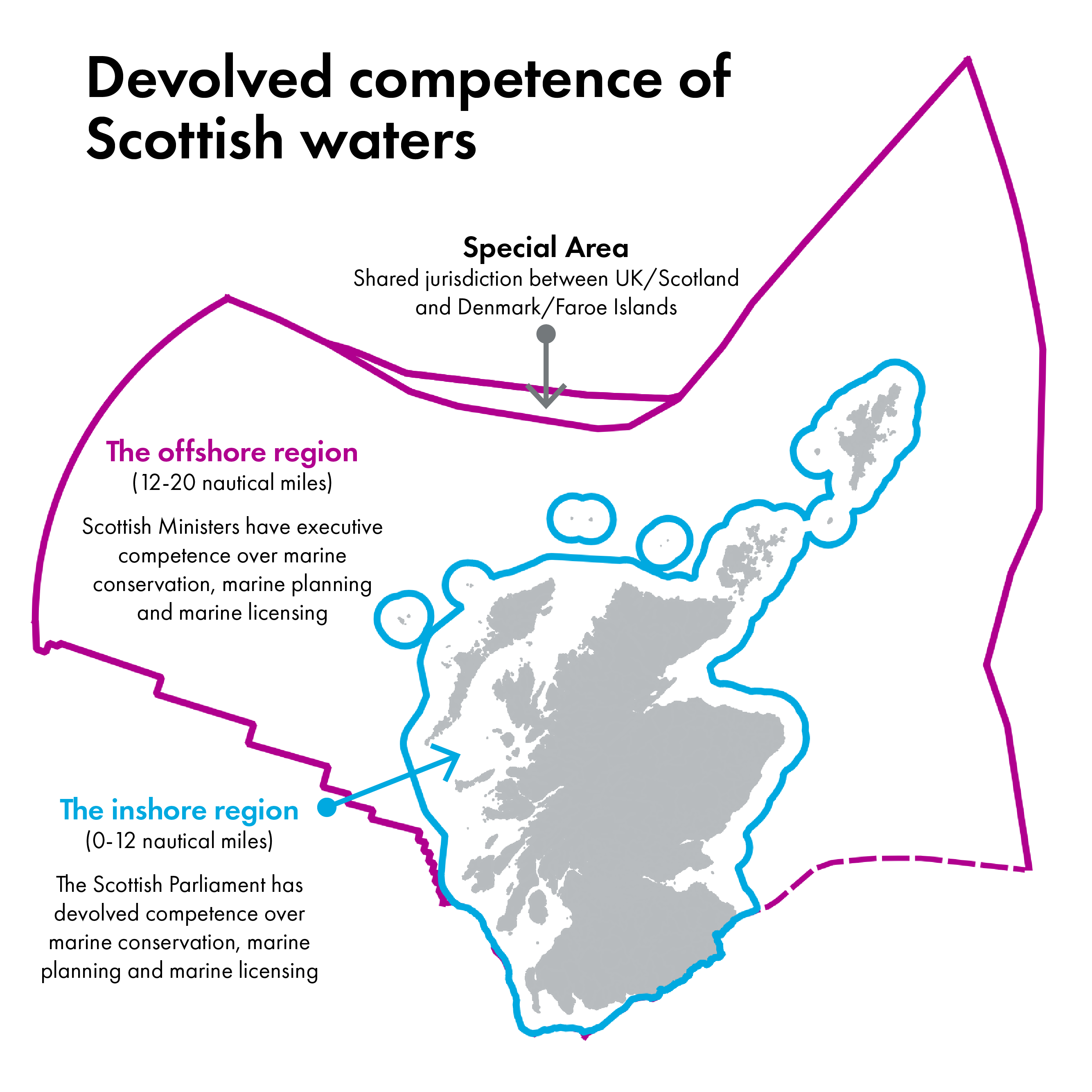

The one substantial difference in fisheries relations with the Faroe Islands is the existence of the ‘Special Area’ under the maritime boundary agreement between the UK and Denmark on behalf of the Faroe Islands. In this area, the two parties have agreed to share jurisdiction over various maritime activities, including fishing.

The Special Area is included within the limits of the UK Exclusive Economic Zone, but it is subject to special rules reflecting the fact that activities within the area may also be managed by the Faroe Islands. Therefore, within the Special Area, each party may apply its rules and regulations concerning the management of fishing, including the issuing of fishing licences. At the same time, each party must refrain from action which would infringe upon the exercise of fisheries jurisdiction by the other party, including the inspection or control of fishing vessels which operate in the Special Area under the authority of the other party.

This is recognised in section 44 of the Fisheries Act 2020, which provides that any prohibition, restriction or obligation relating to sea fishing imposed by any enactment will not apply to anything done by a vessel which is ‘exclusively’ Faroe Islands regulated.

This provision has some implications for the management of those marine protected areas located in the Special Area, including part of the Wyville-Thompson Ridge SAC, the Darwin Mounds SAC, and the West of Scotland MPA. Environmental groups have expressed concern about foreign-flagged trawlers, some of which may be licensed by the Faroe Islands, fishing in these areas.1

Whilst there may be little direct action that the Scottish Government can take against vessels that are exclusively regulated by the Faroes Islands, the Fisheries Act 2020 does not prevent Scottish Ministers from enforcing fisheries measures against foreign-flagged vessels in the Special Area where they are also operating under a UK licence. The Fisheries Act 2020 requires that the Scottish Ministers prepare and publish a list of vessels that may be subject to control in these circumstances.

As with Norway, the UK did not enter into an agreement with the Faroe Islands on access or quota exchange following the consultations that took place in 2021.

iv. Fisheries relations with Iceland and Greenland

The UK has also entered into memoranda of understanding on enhancing cooperation on fisheries with both Greenland (9 November 2020) and Iceland (11 November 2020). Unlike the more formal agreements with Norway and the Faroe Islands, these instruments simply reflect a willingness of the parties to enter into what they call a ‘fisheries dialogue’ which can address a broad range of fisheries related matters. This includes both capture fisheries and aquaculture, as well as processing and marketing of fisheries products.

These dialogues are expected to take place annually and meetings may include government representatives, but also businesses and fisheries experts. Unlike the consultations with the EU, Norway and the Faroe Islands, these fisheries dialogues are not necessarily expected to routinely discuss access and quota exchange, although such arrangements could take place if it were in the interests of the parties concerned.

d. Action to prevent illegal, unreported, unregulated and unsustainable fishing by foreign fishing vessels

As well as regulating their own fishing fleets in order to ensure that fishing is carried out in a sustainable manner, states are also increasingly expected to take any measures within their power to ensure that other countries do not carry out illegal, unreported or unregulated (IUU) fishing. Thus, according to the International Plan of Action on IUU Fishing, adopted by the FAO in 2001 (see above):

states should embrace measures building on the primary responsibility of the flag State and using all available jurisdiction in accordance with international law, including port State measures, coastal State measures, market-related measures and measures to ensure that nationals do not support or engage in IUU fishing

(International Plan of Action on IUU Fishing, para. 9.3)

and:

national legislation should address in an effective manner all aspects of IUU fishing

(International Plan of Action on IUU Fishing, para. 16).

The UK gives effect to the International Plan of Action on IUU Fishing primarily through Council Regulation (EC) No 1005/2008 'establishing a Community system to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU Regulation)', which forms part of domestic law as retained EU law, as modified. The Scottish Ministers have powers to control the entry into port of foreign vessels and to verify whether fish have been caught lawfully prior to landing and importation (Sea Fishing (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing) (Scotland) Order 2013/189).

Under the IUU Regulation, each fishery administration is also required to individually compile and analyse information on IUU fishing and it must keep a file in respect of each fishing vessel reported as allegedly involved in IUU fishing. A fishery administration is obliged to share such information with other fisheries administrations each time a file on an individual fishing vessel is updated.

If information relating to an individual vessel is sufficient to presume that it may be engaged in IUU fishing, the fisheries administrations may jointly agree that an official enquiry should be carried out. In such cases, the UK Secretary of State must request the flag state of the fishing vessel to investigate the matter and to take appropriate enforcement measures. Depending on the response of the flag state, the Secretary of State may add individual vessels to a list of IUU vessels, after which such vessels will be subject to various restrictions, including:

withdrawal of any valid fishing authorisations from listed vessels;

prohibition on any UK fishing vessel assisting in any way the fishing or processing operations of the listed vessel;

prohibition on listed vessels receiving supplies in a UK port, except in cases of force majeure or distress;

prohibition on importation of fishery products caught by listed vessels.

Vessels may only be removed from the IUU list with the consent of all four UK fisheries administrations.

The IUU Regulation also establishes a list of non-cooperating states, who are subject to similar restrictions. The addition of a state on the list must be done with the agreement of all UK fisheries administrations. Regulations concerning the amendment of the list must also be made with the consent of the fisheries administrations. Engagement with a listed country is carried out by the UK Secretary of State.

Regulation (EU) No 1026/2012 'on certain measures for the purpose of the conservation of fish stocks in relation to countries allowing non-sustainable fishing' is retained EU law concerned with the effective management of shared stocks. It confers powers to take action against countries who are considered to be failing to cooperate in their management. The types of action anticipated by the Regulation include:

restrictions on the importation of fish products;

restrictions on the use of ports;

prohibitions on the exportation of fishing vessels or fishing equipment;

prohibition of joint fishing operations with fishing vessels from the country concerned.

Under this Retained EU law, these powers may be exercised by the Scottish Ministers insofar as they fall within the scope of devolved competence. Any measures adopted using this power are subject to the affirmative procedure. However, several of the measures anticipated under the Regulation touch upon reserved matters, such as trade, and therefore they will fall within the purview of the UK Secretary of State (see below).

3. An overview of fisheries governance in the United Kingdom

In general, fisheries is a devolved matter, meaning that the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government have broad powers to regulate fishing in the Scottish Zone, as well as fishing by Scottish vessels beyond the Scottish Zone.

There are several reserved matters which may have implications for fisheries management. In particular, international relations are reserved, meaning that the UK Government takes the lead in international negotiations with fisheries partners such as the EU, Norway and the Faroe Islands.

The determination of quota through agreement with other fishing nations is an important part of this process and it is ultimately the UK Secretary of State who can decide upon the fishing opportunities available to the UK fleet and how those opportunities are to be divided between the four nations of the UK. This reservation of competence does not prevent the devolved institutions being involved in this aspect of fisheries management however.

Other pertinent restrictions on devolved competence relate to matters that are addressed under the Merchant Shipping Act 1995, navigational rights and freedoms and international trade. In practice, many areas of fisheries management are conducted through evolving common frameworks agreed by all of the relevant UK fisheries administrations, including the Scottish Ministers.

The Fisheries Act 2020 requires the development of a new collaborative framework for fisheries management, including common fisheries objectives and a joint fisheries statement agreed between all of the UK fisheries policy authorities. Fisheries administrations have also agreed on other common rules to manage quota transactions between different parts of the UK fleet and certain licensing functions have been granted to a Single Issuing Authority.

a. Devolution and fisheries governance

Fisheries is generally a devolved matter, meaning that powers to regulate fishing belong to the devolved institutions in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, with responsibility for fisheries management in England falling to the UK Government and the Marine Management Organisation.

Regulation of fishing activity within the Scottish Zone and regulation of Scottish fishing boats wherever they fish is devolved. The Scottish Zone is defined by the Scotland Act 1998 as ‘the sea within British fishery limits (that is, the limits set by or under section 1 of the Fishery Limits Act 1976) which is adjacent to Scotland’ (Scotland Act 1998, s. 126) and it encompasses waters within the territorial sea and the Exclusive Economic Zone (see Figure 3). The border between the Scottish Zone and adjacent waters subject to the jurisdiction of other UK fisheries administrations is set by the Scottish Adjacent Waters Boundary Order 1999.

Because fisheries are a devolved matter, many of the powers that were exercised at the EU level before Brexit are now held by the Scottish Ministers (see retained EU law Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy (as modified), article 1). The devolution of fisheries is further consolidated by the Fisheries Act 2020, which confers a broad regulatory power on the Scottish Ministers to make regulations within the scope of devolved competence for a conservation purpose or for a fish industry purpose. (Fisheries Act 2020, Sch 8, para 1; see further below). The UK Government may only apply regulations to the Scottish Zone with the consent of the Scottish Ministers. (Fisheries Act 2020, s. 40).

b. Reserved matters

Some important policy areas related to fisheries are reserved, including international relations, the regulation of maritime transport, and many aspects of taxation, and trade.

Given the international framework for fisheries management described above, the reservation of some aspects of international relations, in particular negotiation of international agreements and regulation of trade, is potentially an important constraint on the powers of the Scottish institutions. These reservations have particular implications for the negotiation of internationally agreed catch and effort limitations, which are ultimately the responsibility of the UK Government (see below).

However, the reservation of international relations only applies to formal diplomatic relations with territories outside the UK. Scottish Ministers have explicit responsibilities to observe and implement international obligations and they are permitted to ‘assist Ministers of the Crown in relation to any matter’ covered by the exception. (Scotland Act, Sch 5, para 7)

The Concordat on International Relations agreed between the UK Government and the devolved administrations recognises that the devolved administrations will have an interest in those aspects of international affairs which touch upon devolved matters, such as fishing. In practice, this means that international negotiations relating to fisheries are carried out by the UK Government with the input of the Scottish Government. The revised arrangements for UK intergovernmental relations announced in March 2021 are likely to affect how preparations for participation in international negotiations will be organised. Under this structure, fisheries is considered by the Inter-Ministerial Group for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

The reservation on international relations does not apply to the implementation of international obligations and the Fisheries Act 2020 confirms that Scottish Ministers may adopt regulations for the purposes of implementing an international obligation of the United Kingdom relating to fisheries, fishing or aquaculture, for example to give effect to the recommendations of a Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (Fisheries Act 2020, Schedule 8, para. 1).

A number of other incidental, but important aspects of maritime regulation are also reserved matters (Scotland Act, Schedule 5). For example:

Registration of fishing vessels under the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 (this is different to the license required to catch fish);

Rules relating to the construction, surveying and certification of fishing vessels;

Rules relating to the prevention of collisions at sea;

Qualifications and training of seafarers, as well as safety on board vessels

Navigational rights and freedoms

As such, these issues are dealt with by the UK Department for Transport and the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency.

Finally, trade and many aspects of taxation are reserved matters. Given the increasing importance of market-access rules for seafood exports, this aspect of fisheries governance is likely to play a more prominent role in the future.

c. Common frameworks in the field of fisheries

Although the power to regulate fisheries is devolved, fisheries management is a subject matter which requires close cooperation between the different fisheries administrations across the UK, particularly where fish stocks cross administrative boundaries. At the Joint Ministerial Committee in October 2017, a set of principles for the development of common frameworks were agreed, which emphasised the role for common frameworks in ‘the management of common resources’ such as fish stocks, among other things.1

A common framework is generally understood as ‘a consensus between a Minister of the Crown and one or more devolved administrations as to how devolved or transferred matters previously governed by EU law are to be regulated after IP [implementation period] completion day.’ (UK Internal Market Act 2020, section 10(4)). IP completion day was 11pm on 31 December 2020.

In practice, a common framework may be statutory or non-statutory and ‘may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued.’.1

A number of different common frameworks have been developed in the field of fisheries and maritime affairs, in particular under the Fisheries Act 2020, but also under related instruments discussed in the following section.

d. UK Rules and Arrangements relating to Fisheries Management

i. The Fisheries Act 2020

Background and Overview

The Fisheries Act is a flagship piece of legislation which serves to mark the transition from the UK being an EU Member State bound by the Common Fisheries Policy to an independent coastal state able to determine its own fisheries regulations and policies. A previous version of the Fisheries Bill had been introduced to the House of Commons in October 2018 but it failed to complete its passage before the end of the session.

This first draft of the Bill introduced in 2018 was opposed by the Scottish Government on the grounds that it encroached on devolved competence (see SPICe Briefing on the UK Fisheries Bill). Before a new Bill was introduced into the House of Lords in January 2020, further engagement took place between the UK Government and the devolved administrations. As a result, the Scottish Government was able to support the later version of the Fisheries Bill and a the Scottish Parliament granted legislative consent on 9 September 2020.

The Bill completed its passage through the House of Commons and the House of Lords on 12 November 2020 and it received Royal Assent on 23 November 2020. The Fisheries Act contains a number of provisions which establish a common framework within which the UK Government and the devolved administrations shall develop fisheries law and policy. This framework includes both common principles and shared processes.

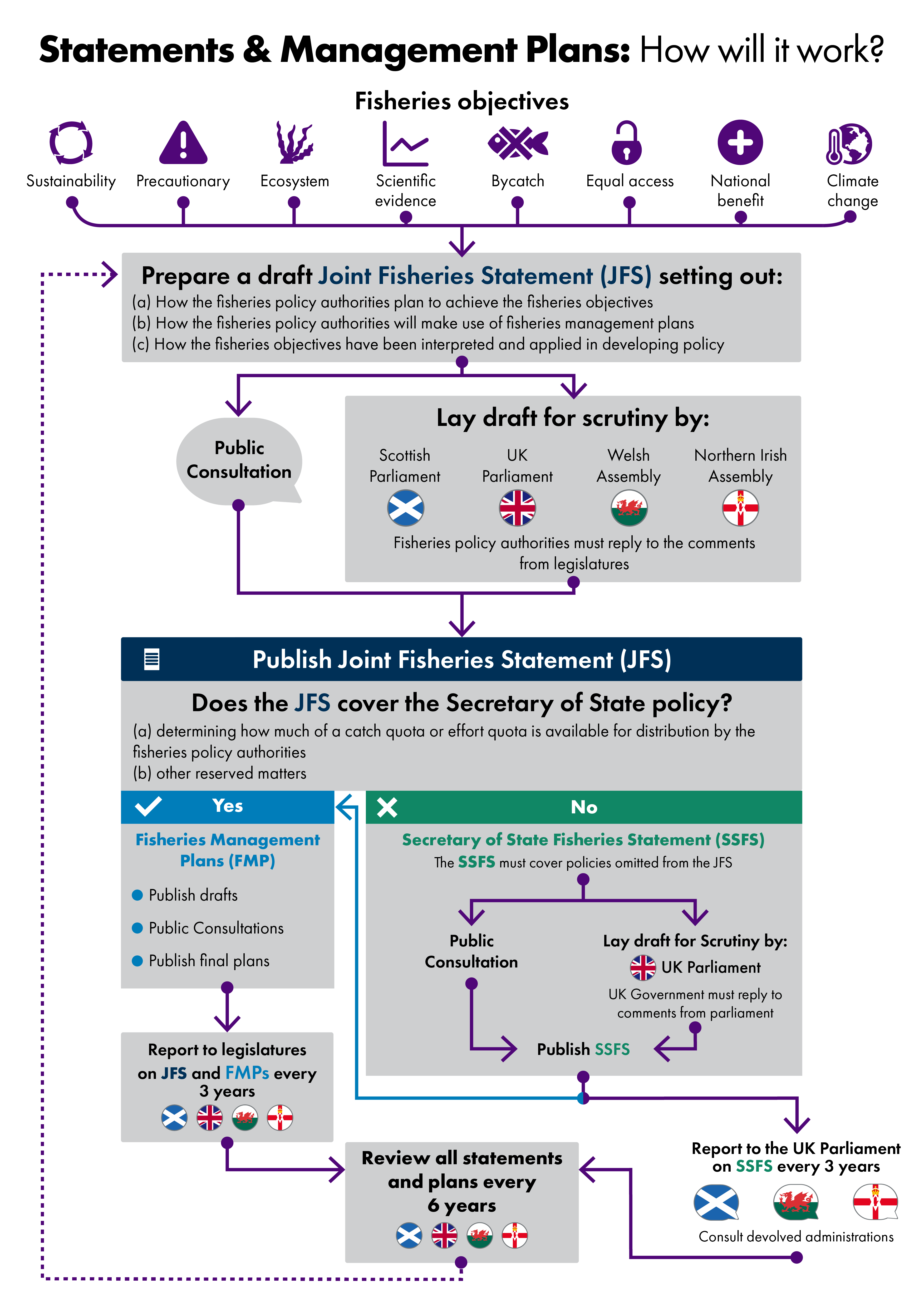

Common Fisheries Objectives

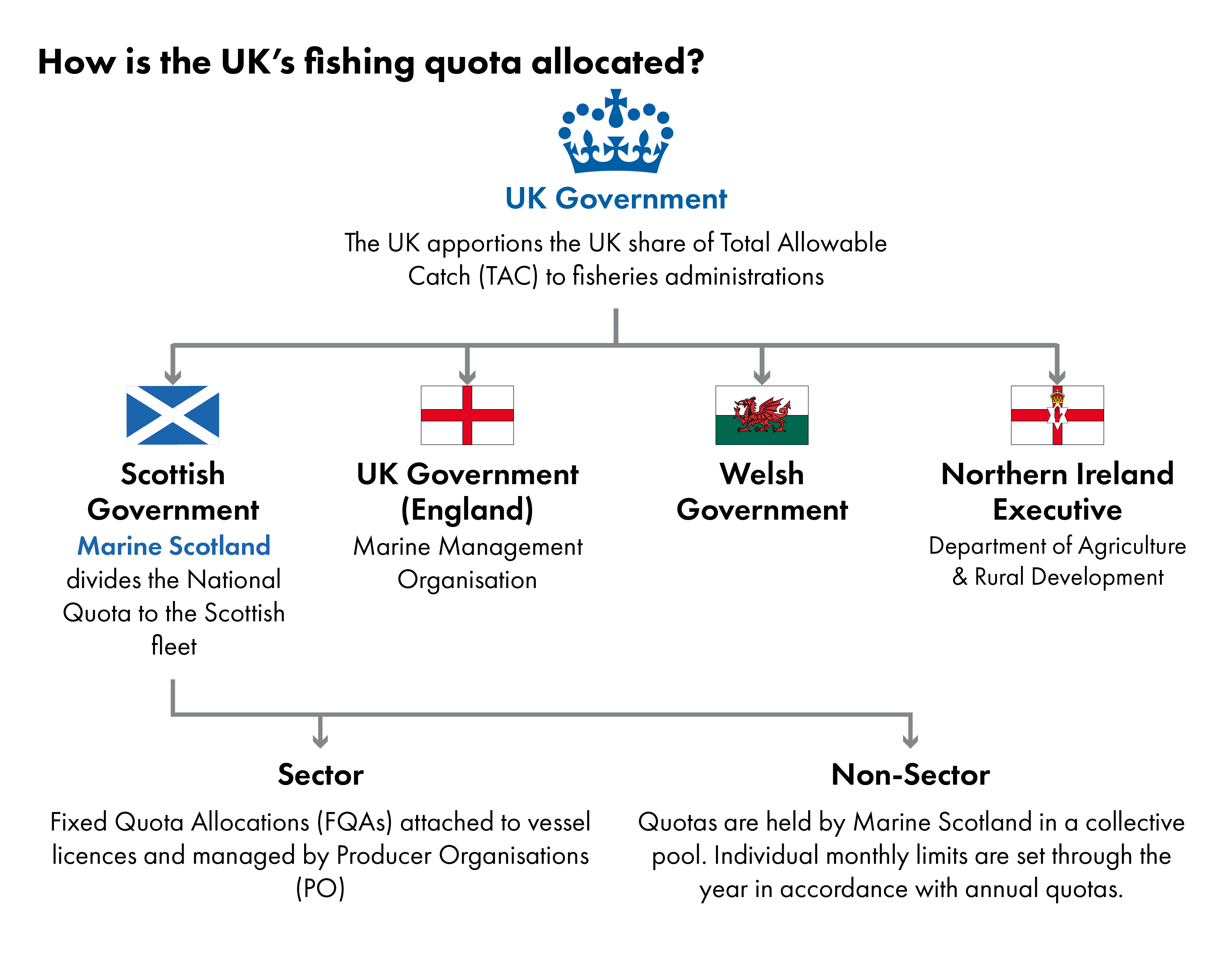

Section 1 of the Fisheries Act 2020 establishes eight high-level fisheries objectives which should guide the regulatory activities of all fisheries policy authorities across the UK. The fisheries policy authorities are the Scottish Ministers in Scotland, the Marine Management Organisation in England, the Welsh Government in Wales, and the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs in Northern Ireland. The objectives are:

the sustainability objective;

the precautionary objective;

the ecosystem objective;

the scientific evidence objective;

the bycatch objective;

the equal access objective;

the national benefit objective; and

the climate change objective.

Most of these objectives apply to both fisheries and aquaculture. The objectives are very general in nature and they leave room for interpretation when being applied in practice. Indeed, different objectives may occasionally be in tension and it will be for fisheries policy authorities to determine how to balance the relevant objectives. Further guidance on how the fisheries objectives should be interpreted by fisheries policy authorities will be set out in a Joint Fisheries Statement to be collectively developed by the fisheries policy authorities (see below).

Many of the objectives in section 1 of the Act are similar to those pursued under the Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union. The national benefit objective and the climate change objective are both additions which have no equivalent under the previous EU rules. The ‘national benefit objective’ provides that fishing activities of UK fishing boats should bring social or economic benefits to the UK or part of the UK. The ‘climate change objective’ provides that the adverse effect of fish and aquaculture activities on climate change should be minimised and these activities should also adapt to climate change.

Another objective that assumes a particular significance in the system of devolved fisheries management in the UK is the ‘equal access objective’, according to which ‘the access of UK fishing boats to any area within British fishery limits is not affected by the location of the fishing boat's home port or any other connection of the fishing boat, or any of its owners, to any place in the United Kingdom.’ (Fisheries Act 2020, s. 1(7)).

In other words, English, Welsh, and Northern Irish fishing vessels should in principle be permitted to fish in the Scottish Zone and Scottish fishing vessels should in principle be permitted to fish in other parts of the UK. Such vessels will nevertheless be subject to the legal requirements imposed by the fisheries administration responsible for the area in which they are fishing.

Joint Fisheries Statement

The fisheries policy authorities in the UK are required to prepare and publish a document known as a Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS). The JFS should both set out the policies adopted by the fisheries policy authorities - individually or jointly – to achieve the fisheries objectives, as well as how the fisheries objectives have been interpreted and applied in formulating those policies.

The legislation is clear that fisheries policy authorities are not required to adopt the same policy in all cases and the JFS may indicate divergences in policy between the four UK nations where they exist. One exception is where the fisheries policies authorities cannot agree on policies relating to the determination of UK catch quotas and effort quotas or policies relating to reserved matters. In that case, these issues must be addressed through a separate Secretary of State Fisheries Statement (SSFS). The SSFS is to be prepared by the UK Secretary of State and a draft must be laid before the UK Parliament before adoption.

In addition to fisheries policies, the JFS must explain how the fisheries policy authorities propose to use fisheries management plans (FMPs) to contribute to the achievement of the fisheries objectives (see below).