The European Union's response to COVID-19

The EU response to the COVID-19 pandemic has focussed on providing additional support to its Member States. This support has taken on two significant strands - on public health and an economic and financial response. This briefing provides details of the EU's response. Cover photo by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash

Executive Summary

The battle against the Coronavirus COVID-19 has taken up the time and resources of governments across the EU. In addition, the EU institutions have been able to provide a supporting role both in terms of coordination of public health related actions and in terms of economic and financial support. The EU is in effect looking to add value to the efforts of its Member State governments in tackling COVID-19.

Member State governments have agreed the following joint EU priorities for tackling COVID-191:

Limiting the spread of the virus.

Ensuring the provision of medical equipment.

Boosting research for treatments and vaccines.

Supporting jobs, businesses and the economy.

The EU's institutional response has been led predominantly (though not exclusively) by the European Commission, and meetings of members of the European Council. The European Parliament and European Central Bank have also played important roles.

The EU public health response consists of:

Direct financial support for procurement programmes to support healthcare systems.

Support for research into treatments and vaccines.

Medical guidance for Member States.

Coordinating the supply and manufacturing of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

The EU's main economic response has come through proposals for the European Commission to make use of the EU budget to tackle COVID-19. In addition, the European Investment Bank and the European Central Bank have made finance available to member states. The key Commission initiatives are:

Corona Response Investment Initiative.

The SURE instrument to protect jobs and people at work.

The European Commission has also amended its regulatory framework in the form of temporary State Aid rules for Member States and by easing member state budget rules ensuring fiscal flexibility to allow member state government's to spend money supporting healthcare and the economy during the COVID-19 crisis.

In relation to the economic response to COVID-19, some experts have suggested that the EU has not stepped up to the plate due to Member States putting national interests first.

The EU has now unveiled exit and recovery strategies including A European roadmap to lifting coronavirus containment measures and the Joint Roadmap for Recovery, which defines four key areas for action:

Single market,

Massive investment efforts,

EU global action and

Better governance.

Context - shared EU and member state competence

The battle against the Coronavirus COVID-19 has taken up the time and resources of governments across the EU. In addition, the EU institutions have been able to provide a supporting role both in terms of coordination of public health related actions and in terms of economic and financial support.

Whilst healthcare is a competence of Member States, Article 4 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU gives the EU shared competence to act in public health matters where there are common safety concerns1.

As a result, according to the European Commission:

The EU is mobilising all resources available to help Member States coordinate their national responses, and this includes providing objective information about the spread of the virus and effective efforts to contain it.

European Commission. (n.d.) The common EU response to COVID-19. Retrieved from https://europa.eu/european-union/coronavirus-response_en [accessed 20 May 2020]

The EU's role in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is underpinned by Decision No 1082/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on serious cross-border threats to health.3 The aim of this decision, agreed in 2013, was to improve preparedness and strengthen capacity for a coordinated EU response to health emergencies. According to the European Commission, the legislation "was an important step forward in improving health security in the EU and in protecting citizens from a wide range of health threats".

The legislation provides a legal basis for the following EU actions to counter pandemics and serious cross-border threats by:

Strengthening preparedness planning capacity at EU level by reinforcing co-ordination and best practice and information sharing on national preparedness planning.

Improving risk assessment and management of cross-border health threats including for non-communicable diseases for which no EU agency is in charge.

Establishing the necessary arrangements for the development and implementation of joint procurement of medical countermeasures.

Enhancing the coordination of an EU-wide response by providing a solid legal mandate to the Health Security Committee to co-ordinate preparedness.

Strengthening the coordination of risk and crisis communication, and fostering international cooperation.

The EU is in effect looking to add value to the efforts of its Member State governments in tackling COVID-19.

The EU response - a summary

In addition to their own domestic actions, Member State governments have agreed the following joint EU priorities for tackling COVID-191:

Limiting the spread of the virus.

Ensuring the provision of medical equipment.

Boosting research for treatments and vaccines.

Supporting jobs, businesses and the economy.

The EU's response can be loosely categorised as three pronged:

An institutional response.

A public health response.

An economic response.

This short briefing sets out some of the key elements of the EU's response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The EU institutional response

The EU's institutional response has been led predominantly (though not exclusively) by the European Commission, and meetings of members of the European Council. The European Parliament and European Central Bank have also played important roles. The following section provides examples of the EU's institutional response to COVID-19.

The European Council

Members of the European Council met by videoconference on 10 March 2020. At that meeting Member State governments agreed the four priorities for EU action1.

Members of the European Council met with the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, on 17 March. European Council members used the meeting to reaffirm their commitment to the four priorities previously identified2.

European Council members met again on 26 March. At that meeting, Member State governments took stock of the EU's response to tackling COVID-19. The conclusions published after the meeting set out the EU's actions across its identified priorities3.

On 23 April European Council members discussed EU exit strategies from the virus along with the economic response to the crisis4.

The European Commission

The European Commission's role is to coordinate the work of the EU and to carry out the policies agreed by Member State governments. In the case of the EU's response to COVID-19, this is also the case.

The Commission is coordinating the EU response through the coronavirus response team1, comprised of Urusla von der Leyen (the Commission President), along with 5 Commissioners:

Commissioner Janez Lenarčič - crisis management.

Commissioner Stella Kyriakides - health issues.

Commissioner Ylva Johansson - border-related issues.

Commissioner Adina Vălean - mobility.

Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni - macroeconomic aspects.

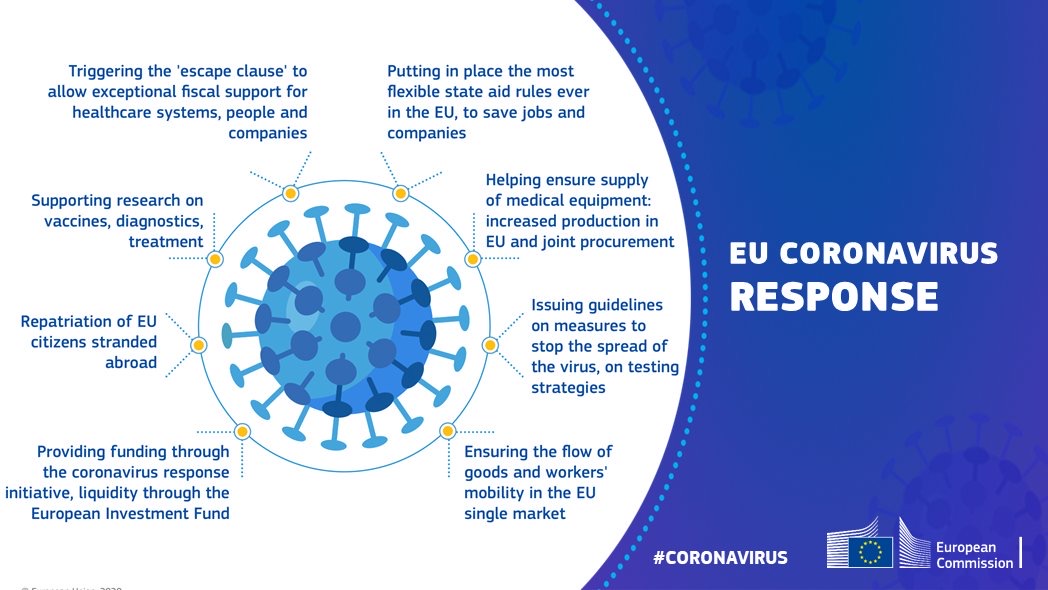

The European Commission has produced an infographic showing what is happening to tackle the pandemic:

The European Commission has proposed a number of legislative and non-legislative initiatives - these are covered later in this briefing, in the sections outlining the public health and economic responses to COVID-19.

The European Parliament

As one of the EU's legislative bodies, the European Parliament has worked with the European Commission to pass a number of legislative initiatives to assist in the fight against COVID-19. For example, during its plenary session on 16-17 April, the European Parliament agreed measures to facilitate1:

Maximum flexibility to channel EU structural funds not yet used, to fight impact of Covid-19 on people.

Enhanced support to EU fishermen, aquaculture farmers and agri-food producers.

Plans to free up more than €3 billion2 to support EU countries’ healthcare systems.

Adopted a resolution calling for a massive recovery package. and;

A Coronavirus Solidarity Fund.

The measures were able to come into force once they received approval from Member State governments in the appropriate EU sectoral council.

Eurogroup response

The Eurogroup, the meeting of Member State finance ministers whose currency is the Euro, held its first discussion about the impact of COVID-19 on the economy at its meeting on 4 March. The conference call also included non-Eurozone EU Member States. In a statement released after the meeting, the Eurogroup made clear its determination to do everything necessary to address the economic impact of COVID-19:

Given the potentially significant impact of COVID-19 on growth, including through the disruption of supply chains, we are committed to coordinate our responses and stand ready to use all appropriate policy tools to achieve strong, sustainable growth and to safeguard against the further materialisation of downside risks. We stand ready to take further coordinated policy action, including fiscal measures, where appropriate, to support growth. The SGP provides for flexibility to cater for unusual events outside the control of governments.

Council of the European Union Eurogroup. (2020, March 4). Statement on the situation with COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/03/04/statement-on-the-situation-with-covid-19/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

At its meeting on 9 April, the Eurogroup agreed a "comprehensive economic response" to COVID-19. This response was endorsed by the European Council on 23 April. Elements of the package endorsed by the Eurogroup are described in the economic response section of the briefing.

Public health response

The EU public health response consists of:

Direct financial support for procurement programmes to support healthcare systems.

Support for research into treatments and vaccines.

Medical guidance for Member States.

Coordinating the supply and manufacturing of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

Procurement of medicines and medical equipment

The EU has allocated €3 billion from the EU budget, matched with €3 billion from the Member States, to fund its procurement activities. These are:

The Emergency Support Instrument; and

The rescEU stockpile of equipment.

These initiatives are set out in Boxes A and B below. In addition to these measures, the EU has utilised its Joint Procurement Agreement (JPA) to assist Member States in obtaining PPE, ventilators and testing kits. The JPA was set up in 2009 after the H1N1 ('Swine Flu') pandemic highlighted weaknesses in the access and purchasing power of EU countries to obtain pandemic vaccines and medications.

Under the JPA, the EU seeks suppliers for goods, and secures contracts through which Member States can then purchase equipment . In a recent blog for the UK in a Changing Europe, Dr Mark Flear explains that "Joint procurement helps to optimise economies of scale and produce countermeasures as cheaply and quickly as possible."1

So far the EU has launched 4 joint procurements of personal protective equipment with Member States:

28 February: Call for hand and body protection.

17 March: Two calls, the first covering face masks, gloves, goggles, face-shields, surgical masks, overalls and the second for ventilators.

19 March: Joint procurement on testing kits.

Under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU, the UK has continued access to these initiatives until the transition period ends on 31 December 2020. However, the UK decided not to participate in the JPA rounds for ventilators and PPE. Media reporting has highlighted confusion around why this decision was taken.

These schemes are in their early stages, so it remains to be seen how effective the scheme will be in helping Member States tackle the pandemic. So far, the European Commission has reported that the JPA has "proven successful", stating that "Producers made offers covering and in some cases even exceeding the quantities requested by the Member States that take part in the procurement, for every single item requested."

However, at the time of writing, it is not clear whether Member States have received items purchased through the scheme. A recent media article (Guardian, 22 April) reported that the EU has warned Member States that it could take as long as a year for all deliveries of ventilators to arrive.2

Box A: The EU Emergency Support Instrument (ESI)

The ESI has a budget of €2.7 billion from the EU. The European Commission states that the ESI "provides strategic and direct support across Member States, in particular as concerns the healthcare sector, to address the COVID-19 emergency, mitigate the immediate consequences of the pandemic and anticipate the needs related to the exit and recovery."

The ESI serves as a flexible and adaptable top-up to existing national and EU support measures to tackle the ongoing health crisis. There are no specific allocations for Member States - funds will be allocated by a Task Force established by the Commission comprising experts in crisis management, health policy, transport, EU public procurement and financial management to allocate funding where it is most needed.34

Examples of actions include:

purchasing and distributing medical supplies.

help with importing and transporting medical equipment and across EU countries.

assisting with the cross-border transport of patients to hospitals with free capacity.

supporting the construction of mobile field hospitals.

Box B: The EU rescEU initiative

In March 2019, the EU reinforced and strengthened all components of its disaster risk management by upgrading the EU Civil Protection Mechanism. This resulted in the European Commission establishing its 'rescEU' initiative with the objective of improving both the protection of citizens from disasters and the management of emerging risks.5

RescEU has been utilised in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to create a common stockpile of equipment such as ventilators and PPE. The stockpile is hosted by one or several Member States. The hosting State is responsible for procuring the equipment. The Commission finances 90% of the stockpile. The Emergency Response Coordination Centre manages the distribution of the equipment to ensure it goes where it is needed most.6

Romania and Germany were the first host Member States of the initiative which has so far led to the delivery of 330,000 protective masks being delivered to Italy, Spain and Croatia.7

Availability of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

The European Commission lists the following activities in addition to the procurement activities summarised in the previous section:

Ramping up production of personal protective equipment (PPE): helping ensure an adequate supply of PPE across Europe, working closely with Member States to assess the available stock of PPE in the EU, the production capacity and anticipated needs.

Publishing a recommendation on conformity assessment and market surveillance to increase the supply of certain types of PPE, such as disposable facemasks, to civil protection authorities, without compromising health and safety standards.

Discussing with industry how to convert production lines to supply more PPE. The Commission also provided manufacturers with guidance to increase production in three areas:

masks and other PPE.

hand sanitizers and disinfectants; and

3D printing.

Making European standards for medical supplies freely available to allow producers to get high-performing devices on to the market more quickly.

Introducing the requirement for an export authorisation for Member States when exporting PPE outside the EU to ensure supply within the EU. Member States can grant authorisations where no threat is posed to the availability of such equipment in the Union, or on humanitarian grounds.

Support for research on treatment, diagnostics and vaccines

The EU has provided support for research to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic through direct investment and through its Coronavirus Global Response pledging marathon.

Direct investment

The EU Commission's overview of its response to the COVID-19 pandemic lists the following direct investment to support research1:

Over €380 million to develop vaccines, new treatments, diagnostic tests and medical systems.

€48.25 million granted to 18 projects and 151 research teams from Horizon 2020 research and innovation funding programme.

An emergency call launched through the Innovative Medicines Initiative funded by up to €45million from Horizon 2020, to be matched by the pharmaceutical industry.

€80 million of support in the form of an EU guarantee of an European Investment Bank loan to CureVac, a European vaccine developer. The company aims to launch clinical testing of a vaccine by June 2020.

A European Innovation Council Accelerator call of €164 million attracting "a significant number" of start-ups and businesses with innovations that could help tackle the pandemic.

During the transition period, UK scientists, researchers and businesses can continue to participate in and lead Horizon 2020 projects and apply for Horizon 2020 grant funding. Participants continue to receive EU grant funding for the lifetime of individual Horizon 2020 projects, including projects finishing after 31 December 2020 when the transition period ends.

It is not clear whether UK researchers will be able to apply for EU research grant funding after 31 December 2020. This will depend on the outcome of the future relationship negotiations. The UK Government has indicated in its approach to negotiations that it will "consider a relationship in line with non-EU Member State participation" in EU research programmes such as Horizon Europe, the EU's €100 billion research and innovation programme that will succeed Horizon 2020. 234

Coronavirus Global Response pledging marathon

On 4 May, The EU initiated its Coronavirus Global Response pledging marathon. Its stated aim is "to gather significant funding to ensure the collaborative development and universal deployment of diagnostics, treatments and vaccines against coronavirus."5

The pledging marathon aims to raise €7.5 billion of funds that the World Health Organization says is needed for developing solutions to test, treat and protect people, and to prevent the disease from spreading. The European Commission says that it registers and keeps track of pledges (from both EU member states and other donors) but will not receive any payments into its accounts. Funds go directly to the recipients. Recipients listed are:

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) for vaccines.

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance for vaccine deployment (related to coronavirus).

Therapeutics Accelerator for therapeutics.

UNITAID for therapeutics deployment (related to coronavirus).

Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) for diagnostics.

The Global Fund for diagnostics deployment (related to coronavirus).

The World Health Organization (WHO) for health systems (related to coronavirus).

At the time of writing, the initiative had received pledges worth €7.4 billion.

Guidance for Member States

In March 2020, the European Commission launched a panel of 7 independent epidemiologists and virologists to provide guidelines on science-based and coordinated risk management measures and advise on:

Response measures for all Member States.

Gaps in clinical management.

Prioritisation of health care, civil protection and other resources. and

Policy measures for long-term consequences of coronavirus.1

The Commission lists the following timeline of key guidance it has issued:

19 March: recommendations on community measures, such as social distancing.

15 April: guidelines on testing methodologies, to support the efficient use of testing kits by Member States.

16 April: guidance on how to develop tracing mobile apps that fully respect EU data protection rules.

Economic response

Much of the EU's response to COVID-19 has focussed on providing economic and financial support both to Member States and also to stakeholders within member states. The EU has also provided funding to neighbouring countries to assist the fight against COVID-19.

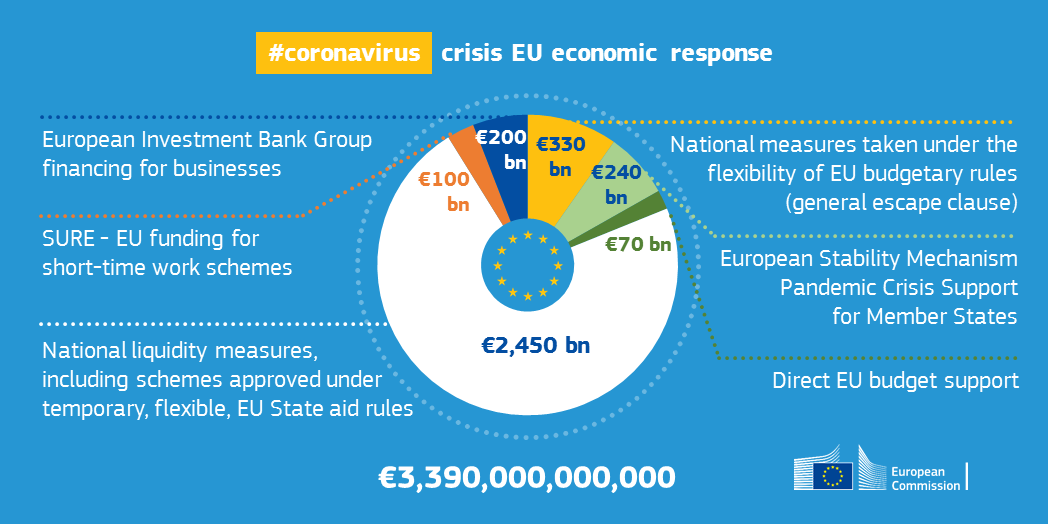

The EU's main response has come through proposals for the European Commission to make use of the EU budget to tackle COVID-19. In addition, the European Investment Bank and the European Central Bank have made finance available to member states.

The next section provides examples of the EU's economic and financial support available to Member States. It does not cover every example of the support available, for instance in providing specific funding to different sectors of the economy.

European Commission proposals

The European Commission's economic and financial proposals centre on making use of the EU budget to support Member State efforts to tackle COVID-19. The key Commission initiatives are:

Corona Response Investment Initiative.

The SURE instrument to protect jobs and people at work.

The European Commission has also amended its regulatory framework in the form of temporary State Aid rules for Member States and by easing member state budget rules ensuring fiscal flexibility to allow member state government's to spend money supporting healthcare and the economy during the COVID-19 crisis.

The Corona Response Investment Initiative

The European Commission has proposed that around €37 billion of cohesion funds (structural and investment funds) should be redirected towards offsetting the economic impact of COVID-19. This new initiative will use funds from the EU budget and will be raised by using underspent structural and investment funds across Member States along with €29 billion of unallocated funds left during the 2014-2020 programme period.

According to the European Commission:

The Commission is also making all Coronavirus crisis related expenditure eligible under cohesion policy rules. It will also be applying the rules for cohesion spending with maximum flexibility, thus enabling Member States to use the funds to finance crisis-related action. This also means providing greater flexibility for countries to reallocate financial resources, making sure the money is spent in the areas of greatest need: the health sector, support for SMEs, and the labour market.

Finally, the Commission is proposing to enlarge the scope of the EU Solidarity Fund – the EU tool to support countries hit by natural disasters – to support Member States in this extraordinary situation.

European Commission. (2020, March 13). European Coordinated Response on Coronavirus: Questions and Answers. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_458 [accessed 20 May 2020]

The Corona Response Investment Initiative is based upon three key pillars:

It consists of €37 billion of EU funding and will not require any money from Member States national budgets.

The spending rules around the funding will be treated flexibly meaning that according to the Commission, all Coronavirus related expenditure will be eligible under structural funds. As a result, the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund can all be used to provide funding associated with addressing the consequences of COVID-1923.

The European Solidarity Fund will also be made available to member state applications providing access to additional further EU support of up to €800 million.

As the UK continues to participate in EU funding programmes during the transition period, the UK has also been able to use its structural and investment funds allocation to tackle COVID-19. The Commission has suggested that €555 million for the Corona Response Investment Initiative will be available to the UK as part of its structural and investment funds allocation along with a further €2.4 billion on structural and investment funds available to be allocated by the end of the current programme (end of 2020)1.

The SURE instrument to protect jobs and people at work.

The European Commission has allocated €100 billion in the shape of loans from the EU to Member States to provide temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE).

According to the European Commission, the SURE instrument will:

provide financial assistance to Member States to address sudden increases in public expenditure for the preservation of employment. Specifically, the SURE instrument will act as a second line of defence, supporting short-time work schemes and similar measures, to help Member States protect jobs and thus employees and self-employed against the risk of unemployment and loss of income.

European Commission. (n.d.) A European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-financial-assistance/loan-programmes/sure_en [accessed 20 May 2020]

The draft SURE regulation sets out that the instrument will not apply to the UK during the transition period because the financial liabilities potentially incurred by the instrument would not be covered by the Withdrawal Agreement and as such the UK is ineligible to participate2.

Temporary State Aid rules

On 19 March 2020, the European Commission published a Temporary Framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak. The measures proposed by the Commission allow Member State governments (and the UK government during the transition period) to provide public funding to businesses to ensure continued liquidity which has been threatened as a result of COVID-19. The Temporary Framework will be in place until the end of December 2020 but will be reviewed before it is due to expire1.

Whilst the temporary framework provides more scope for Member State governments to provide public funding to businesses, any schemes still require the approval of the European Commission.

On 25 March 2020, the European Commission confirmed it had approved two UK schemes to support SMEs affected by coronavirus outbreak. Both the UK government's schemes fall under its Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme which provides support to SMEs2.

Further UK schemes were approved on 6 April (a €50 billion UK “umbrella” scheme to support the economy)3 and 11 May (worth €10.3 billion to support self-employed individuals and members of partnerships)4.

The European Commission has approved a lengthy list of schemes to tackle COVID-19 under the temporary State Aid rules. These include at least one scheme in every Member State and also the schemes referenced above in the UK5.

Easing budgetary flexibility for Member States

Regulations set out in the EU's Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), say that EU countries should have nominal annual budget deficits below 3 percent of economic output and public debt below 60 percent.

The measures deemed necessary by Member State governments to deal with COVID-19 will push Member States far beyond these figures. As a result, for the first time since the policies were introduced in 1997, the European Commission has chosen to trigger the 'escape clause' to allow exceptional fiscal support. This will in effect allow maximum flexibility to the EU's budgetary rules and help Member State governments financially support healthcare systems and businesses, and to keep people in employment during the COVID-19 crisis.

Eurobonds

Perhaps the EU's biggest fissure with regards to its response to COVID-19 revolves around the question of whether to issue Eurobonds (also referred to as Coronabonds) or not. Coronabonds would in effect involve a mutualisation of Member State debt into an EU debt.

Coronabonds were initially rejected by northern European countries such as Germany and the Netherlands who see the potential danger of having to in effect bail out other countries. However, on 19 May, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that, working with French President Emmanuel Macron, they had agreed to a €500 billion recovery fund. According to Politico:

Under the plan, the recovery fund would be fully financed by debt issued by the EU and backed by all 27 members. The money would be distributed by the European Commission in the form of grants as part of the bloc’s normal budget and repaid over the long term by the EU.

Politico. (2020, May 18). Berlin buckles on bonds in €500B Franco-German recovery plan. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/berlin-buckles-on-bonds-in-e500b-franco-german-recovery-plan/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

Despite the apparent u-turn from Germany, the proposal still requires unanimous support and some countries potentially including Austria, the Netherlands and Finland are likely to oppose the plan, or at least try to1. Whether political pressure from other Member States leads to the proposal being accepted remains to be seen.

European Investment Bank

At the start of April, the European Investment Bank (EIB) announced "a €25 billion pan-European guarantee fund to support up to €200 billion for the European economy". The funding will be provided by Member States (in line with their shareholding in the EIB) and will then be loaned by the EIB to to local banks and other financial intermediaries, to provide financial support to businesses and economies in member states. According to the EIB:

By guaranteeing parts of portfolios, our operations under the guarantee fund will free up capital for the financial intermediaries involved to make more financing available for SMEs and mid-caps. Thus, we have calculated that up to €200 billion will become available.

The guarantee fund will provide guarantees to the EIB and EIF to reimburse any possible losses incurred for included operations. By pooling credit risk across all of the European Union, the overall average cost of the fund will be significantly reduced, compared to national schemes.

European Investment Bank. (n.d.) Coronavirus outbreak: EIB Group’s response. Retrieved from https://www.eib.org/en/about/initiatives/covid-19-response/index.htm [accessed 20 May 2020]

European Central Bank

The European Central Bank announced the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) with an available budget of €750 billion until the end of the year. This is in addition to the €120 billion scheme announced on 12 March. Together this amounts to 7.3% of euro area GDP. The programme is temporary and designed to address the unprecedented situation the Eurozone is facing1.

The purpose of the PEPP is to provide temporary finance across the Eurozone by buying private and public sector securities in the shape of private and public sector assets. The scheme is due to run until the end of 2020.

Analysis of the EU's economic response to COVID-19

Whilst a proper assessment of the effectiveness of the EU's collective response to COVID-19 can only really be made after the crisis is over, some experts have begun to provide views on whether the EU as an organisation is stepping up to the plate.

Matt Bevington, writing on the UK in a Changing Europe blog, suggested that whilst the EU has been criticised for its response to COVID-19, in many ways it has done what it could:

The EU has been criticised during the coronavirus outbreak for an apparent lack of solidarity between Member States and poor co-ordination in its response.

However, across a broad range of policies, co-ordination has been about as effective as we could expect given the circumstances.

Bevington, M. (2020, April 23). Criticisms of poor EU co-ordination overblown. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/criticisms-of-poor-eu-co-ordination-overblown/# [accessed 20 May 2020]

Bevington adds that as the crisis has escalated, a more coordinated EU response has developed.

In relation to the economic response to COVID-19, Professsor Iain Begg from the London School of Economics has suggested that the EU has not stepped up to the plate due to Member States putting national interests first. He argues that whilst the EU has agreed a number of measures, largely to be paid for from the current budget, the next EU budget - to run from 2021-2027 has yet to be agreed and it may need a significant increase to support COVID-19 measures. However, the EU budget is financed by Member States, and net contributors may be less keen to provide the necessary funding:

Pinning a response on the EU budget will not be easy. A settlement of the next multi-annual financial framework (MFF), to run from 2021 to 2027, is long overdue. Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, the EU had been gravitating towards a deal around a headline total of about 1.07 percent of EU GDP. Attempts to settle it two months ago were unsuccessful and the expectation had been that it would have to wait until late summer under the German Presidency.

Re-opening the negotiations will take time, and will also re-open the familiar three-way dispute between net contributors, recipients of ‘old’ EU spending and advocates of ‘new’ EU spending...

...The European Council is, manifestly, aware of the need for common action and the dangers of being seen to do too little, too late, and being too caught up in stances rendered obsolete by the severity of the crisis. But EU leaders will need to make some tough choices and some may have to abandon long-held positions.

Begg, I. (2020, April 24). Covid-19: the struggle to agree an EU response. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/covid-19-the-struggle-to-agree-an-eu-response/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

Professor Begg cites further evidence that the EU is still crippled by Member States putting the national interest first is the disagreement between governments about Coronabonds which would in effect involve a mutualisation of Member State debt into an EU debt.2 Coronabonds have thus far been rejected by northern European countries such as Finland and the Netherlands (Germany has now indicated a u-turn on this issue) who see the potential danger of having to in effect bail out other countries. It has even been argued that the row over Coronabonds could threaten the future of the EU4.

The needs of particular Member States will once again come to the fore when the EU decides how big the future EU budget should be and whether it will provide Member States with COVID-19 related grants or loans5. For countries already saddled with large debts, such as Italy and Greece, clearly grants will be more welcome than further loans but once again net contributors to the EU budget may wish to see loans and the possibility of the EU getting its money back at some point. In addition, net contributors are likely to be alarmed at the possibility of a significant increase in their payments into the EU budget.

Professor Anand Menon, Director of the UK in a Changing Europe programme has written a blog examining the EU's divisions over Coronabonds and its overall response to the COVID-19 crisis. He argues that the EU's actions have largely been limited by the actions of its Member State governments:

But there is only so much that the EU can do when it comes to coordinating Member States which, when forced to choose between protecting their citizens and European solidarity, have plumped repeatedly (and understandably) for the former...

...And Member States are also the obstacle when it comes to economic responses. EU actions so far have been far from sufficient to deal with the fallout of the crisis.

Nine eurozone Member States (Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain) have publicly backed the issuance of joint European debt in the form of coronabonds.

Yet mutualised debt issuance is something the so-called ‘frugal states’ vociferously oppose. The Dutch, Austrians and Finns are most strident in their opposition, fearing the weakening of fiscal discipline. The virtual European Council merely kicked the can of the recovery fund down the road.

Menon, A. (2020, April 27). Covid-19’s threat to the EU. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/covid-19s-threat-to-the-eu/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

The EU's economic response to COVID-19 has been to pour money into the problem using the current EU budget. However, longer term structural solutions such as sharing of debt through Eurobonds, or an increased future EU budget have, for now, yet to be agreed. As is often the case with the EU, it does what it can, but significant action is often blocked by the self-interest of its Member States. The economic response to COVID-19 will be a test of the EU's ability to put the collective ahead of national interest.

External financial support

On 5 May, Member State governments agreed a €3 billion package of support for European enlargement and neighbourhood countries to assist them in tackling COVID-19. The support, in the form of loans at favourable rates have been allocated to the following countries1:

Albania: €180 million

Bosnia and Herzegovina: €250 million

Georgia: €150 million

Jordan: €200 million

Kosovo*: €100 million

Moldova: €100 million

Montenegro: €60 million

Republic of North Macedonia: €160 million

Tunisia: €600 million

Ukraine: €1.2 billion

According to the Council of the European Union, these loans will:

Help these jurisdictions cover their immediate financing needs which have increased as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. Together with the support from the International Monetary Fund, the funds will help enhance macroeconomic stability and create space to allow resources to be allocated towards protecting citizens and to mitigating the negative socio-economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic.

Council of the European Union. (2020, May 5). COVID-19: Council greenlights €3 billion assistance package to support neighbouring partners. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/05/05/covid-19-council-greenlights-3-billion-assistance-package-to-support-neighbouring-countries/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

On 6 May, the European Union announced a further package of €3.3 billion for its Western Balkans partners (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia and Kosovo) to support the health sector, social and economic recovery, and provide assistance through the European Investment Bank, as well as micro-financial assistance3.

Borders and mobility

The EU's immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic was to repatriate EU citizens affected by travel restrictions abroad. The EU Civil Protection Mechanism was used to facilitate repatriation flights for 45,122 EU citizens and 1,837 UK citizens to Europe from various countries. Under the EU Civil Protection Mechanism, the Commission contributes to the costs of repatriation flights that carry nationals of more than one Member State.1

A significant effect of COVID-19 was that free movement within the EU has ground to a halt for the first time ever, due to border checks and restrictions. These restrictions are likely to be applied on and off for the foreseeable future. Without a unified approach across Member States, it has been suggested that different measures on free movement could result in long-lasting damage to free movement and EU solidarity.

Further measures are summarised in the timeline below:

16 March: European guidelines for border management measures to protect health and ensure availability of goods and essential services; Temporary restriction on non-essential travel to the EU.

23 March: EU guidelines on 'green lanes' to Member States to ensure speedy and continuous flow of goods across the EU and to avoid bottlenecks at key internal border crossing points.

26 March: Guidance inviting EU Member States to support air cargo operations during the coronavirus crisis in order to keep essential transport flows moving, including medical supplies and personnel.

30 March: Guidance to ensure the free movement of workers, especially in the health care and food sectors.

29 April: The European Commission adopted a package of measures to provide relief to the transport sector by solving practical problems, removing administrative burdens, and increasing flexibility.

7 May: Guidance to Member States address the shortages of health workers.

Tackling disinformation

On 30 March, the Commission launched a webpage on fighting coronavirus-related disinformation, providing materials for myth busting and fact checking.

The Commission states that it is in "close contact" with social media platforms. Commission Vice-President Věra Jourová has also met Google, Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft and others to discuss measures and further action.

Recovery and exit strategies

On 15 April, the European Commission published A European roadmap to lifting coronavirus containment measures. The communication, which was jointly prepared by the Presidents of the European Commission and the European Council sets out a common EU-wide approach to lifting the measures in place as a result of COVID-191.

The Communications key conclusions are:

The correct timing is essential when deciding when to lift containment measures with decisions based on the following criteria:

Epidemiological criteria, indicating a sustained reduction and stabilisation in the number of hospitalisations and/or new cases for a sustained period of time.

Sufficient health system capacity, for example in terms of an adequate number of hospital beds, pharmaceutical products and stocks of equipment.

Appropriate monitoring capacity, including large-scale testing capacity to quickly detect and isolate infected individuals, as well as tracking and tracing capacity.

Decisions should be made based on three common EU principles:

Action should be based on science and have public health at its centre.

Action should be coordinated between the Member States to avoid negative effects.

Respect and solidarity between Member States remain essential to better coordinate, communicate and to mitigate the health and socio-economic impacts.

There should be accompanying measures to phase out confinement including:

Gather data and develop a robust system or reporting on COVID-19 cases.

Create a framework for contact tracing and warning.

Testing capacities must be expanded and harmonised.

The capacity and resilience of health care systems should be increased.

The availability of medical and personal protective equipment should be increased.

Develop and fast-track the introduction of vaccines, treatments and medicines.

In terms of next steps, the communication suggests that action should be gradual and that the general applicable measures currently in place should become targeted, for example at particularly vulnerable groups. Around this time the economy should gradually be reopened and gatherings of groups of people should begin to be permitted. Schools and universities along with retail should reopen.

As measures begin to be lifted, the communication suggests those with a local effect should be lifted first to be followed by measures which have a wider geographic focus. It is also suggested that a phased approach should be adopted to opening the EU's internal, and then external, borders.

Finally, the Communication suggests that efforts to prevent the spread of the virus should be sustained and measures should constantly be reviewed.

Despite this Communication, it has been suggested that the EU is being left behind as Member State governments take unilateral action towards lifting the COVID-19 restrictions. According to a Politico article published in mid-April:

At least half a dozen EU countries have started easing lockdowns, jumping ahead of the European Commission, which on Wednesday will formally unveil its "roadmap" toward lifting containment measures — a document intended to prevent the confusion and lack of coordination that marred the bloc's initial responses to the pandemic.

The un-choreographed announcements in capitals from Copenhagen to Warsaw authorized a haphazard array of steps to begin ending the constraints on businesses and citizens, which have helped reduce the death toll and limit the pressure on health systems, but at a staggering economic cost that has unnerved political leaders.

Polticio. (2020, April 14). EU left behind as capitals plan coronavirus exit strategies. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-left-behind-as-capitals-plan-coronavirus-exit-strategies/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

Politico suggested that whilst the European Commission accepted that the lifting of containment measures was a matter for Member State governments, it demonstrated the "continuing struggle of officials in Brussels to assert themselves in the crisis and better orchestrate decisions across the Continent".

Economic recovery

At their meeting on 23 April, members of the European Council asked the European Commission to urgently come up with a proposal for a recovery fund. Announcing the plan, European Council President Charles Michel said

This fund shall be of a sufficient magnitude, targeted towards the sectors and geographical parts of Europe most affected.

European Council. (2020, April 23). Conclusions of the President of the European Council following the video conference of the members of the European Council, 23 April 2020. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/04/23/conclusions-by-president-charles-michel-following-the-video-conference-with-members-of-the-european-council-on-23-april-2020/ [accessed 20 May 2020]

Significantly, the European Council also agreed to integrate the economic recovery response into the upcoming Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF) covering 2021-2027. Given this new MFF still needs to be agreed, Member State governments agreement that it should include provisions associated with dealing with the COVID-19 fallout will be seen as helpful by the European Commission.

European Council members also welcomed the Joint Roadmap for Recovery, which defines four key areas for action:

Single market,

Massive investment efforts,

EU global action and

Better governance.

It also sets out important principles, such as solidarity, cohesion and convergence.

However, crucially, the EU's economic response will to a serious extent be determined by the decision of Member State governments on whether to agree to Eurobonds or not. In many ways, a unified response to COVID-19 would demonstrate an example of the purpose of the EU in working collectively for the common good. Failure to agree a common properly funded approach could be damaging for the EU as an organisation.