Negotiating the future UK and EU relationship

This briefing sets out the process for negotiating the new economic and security relationship between the UK and the EU after Brexit. It also provides analysis of the key areas of negotiation from a Scottish perspective.

Executive Summary

After the UK leaves the European Union on 31 January 2020 attention will turn to the negotiation of the future relationship between the EU and the UK. The Political Declaration on the Future Relationship (agreed in October 2019) provides an indication of the likely direction for discussions between the UK and the EU. The key aspects of the future relationship are likely to focus on economic and security arrangements.

From the European Union's perspective, its legal infrastructure will guide the process and present challenges in terms of how an agreement is reached and ratified. Article 218 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) sets out the procedure for the EU's negotiation of international agreements with third countries. The process set out in Article 218 is highlighted in the Political Declaration as the process by which the future relationship negotiations should be conducted.

The European Commission has established a new ‘Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom’ (UKTF). Michel Barnier is the Head of the Task Force with responsibility to oversee negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK. He is likely to work closely with the new Head of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen.

There is little detail about the UK Government's intended approach to the negotiations. The provisions of the original Withdrawal Agreement Bill had made reference to a role for the UK Parliament, however, these provisions were removed in the new European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill which was introduced in the House of Commons on 19 December 2019. There is no role in the negotiations on the future UK-EU relationship for the Scottish Parliament or Scottish Government set out in the Withdrawal Agreement Bill.

The European Commission is yet to publish a draft mandate for negotiations. However, recent speeches by Michel Barnier and Ursula von der Leyen have indicated that the Commission believes the depth of the future relationship will be dictated by the UK Government's decision to end free movement and be dependent on the UK Government's approach to level playing field provisions. The European Commission has said it hopes the negotiations can lead to a new partnership with zero tariffs, zero quotas and zero dumping. Alongside this, the EU hopes to secure a partnership that goes beyond trade and also addresses issues such as climate action, data protection, fisheries, energy, transport and financial services along with security.

The UK Government has indicated it will seek a broad free trade agreement covering goods and services, and cooperation in other areas. The Prime Minister has also said that the UK will end freedom of movement and that "any future partnership must not involve any kind of alignment or ECJ jurisdiction". In addition, the UK Government has indicated that it will seek to maintain control of UK fishing waters.

The potential time available for the negotiations is very tight due to the UK Government's pledge that it will not extend the transition period beyond the end of December 2020. Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission President has suggested that the UK Government's insistence on not extending the transition period beyond the end of 2020 would mean that the negotiations would have to focus on a smaller number of priorities and that an all-encompassing future relationship might not be possible in the eleven months available.

In the event the UK Government fails to conclude its desired future relationship with the EU before the end of December 2020, the country will once again face an effective no-deal situation (in relation to trade in goods and services). At this point, however, the UK would not be a member of the EU and there is no clear and obvious way to delay such a no-deal scenario as was possible when seeking three extensions to the Article 50 process in 2019.

Whilst foreign affairs and and international relations are matters reserved to the UK Parliament, observing and implementing international obligations are not reserved. Given the likely breadth of any future relationship negotiated with the EU, it is likely to include obligations in devolved policy areas. The Institute for Government has argued that the UK Government must involve the devolved administrations to properly reflect Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish interests in the talks.

At this stage, no role has been set out for the UK's devolved administrations and legislatures in the UK-EU future relationship negotiations. The Scottish Government has said that it believes that "where there are devolved competences, the decision on those devolved competences must be made by the devolved administrations, not by anybody else". The Scottish Government has also argued that the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament must play a much enhanced role in the development of future trade policy and the preparation, negotiation, agreement, ratification and implementation of future trade deals.

From a Scottish perspective, the key areas of interest during the future relationship negotiations will include:

Level playing field and regulatory alignment

Fisheries

Food and drink and PGIs

Agriculture

Services

Justice and Security

Immigration/Mobility

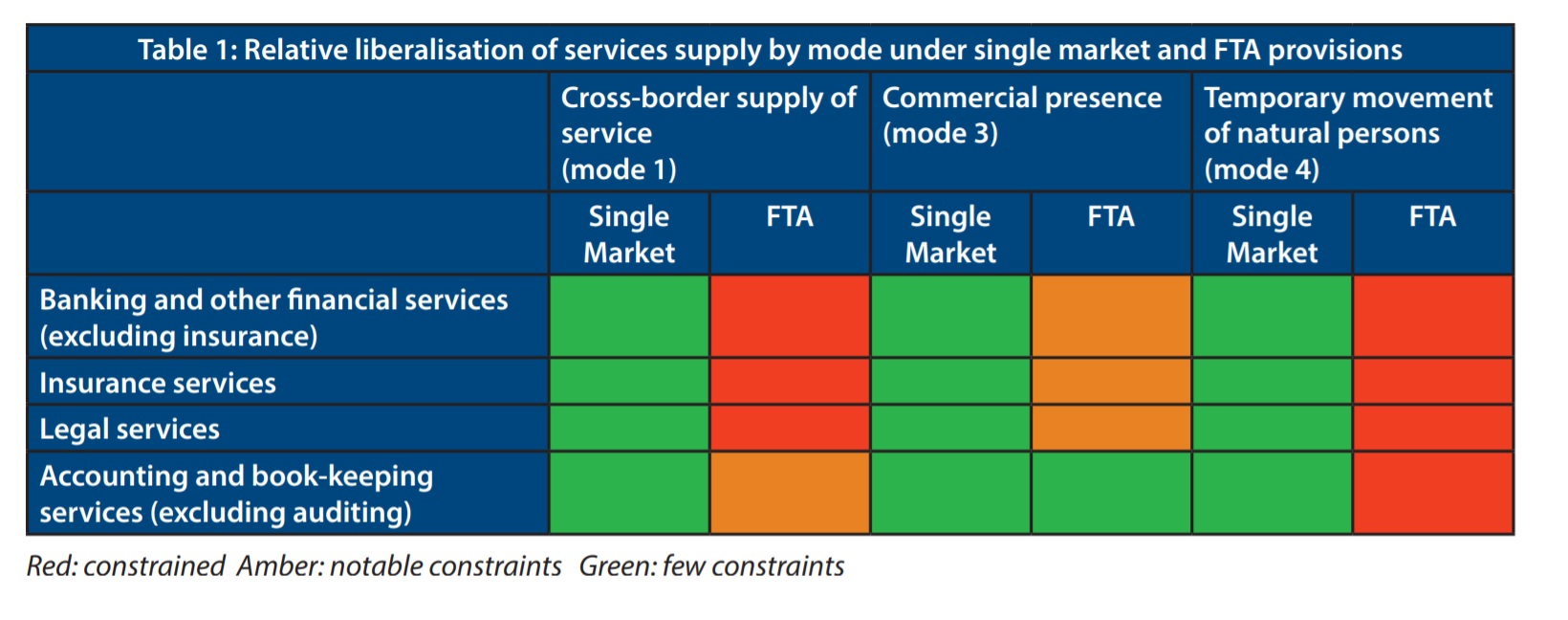

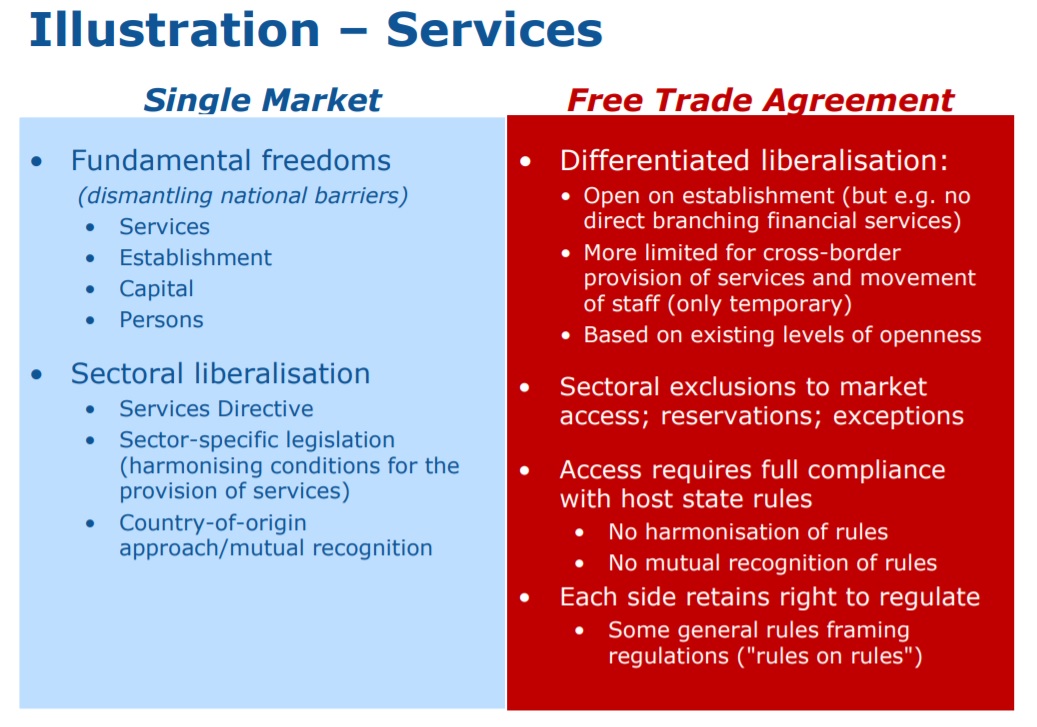

Given both sides' red lines, it is clear that the future relationship cannot provide for the same benefits that the UK enjoys as an EU Member State. This means that in areas such as agriculture and fisheries, ensuring relatively frictionless access to the EU market will be more challenging. For the UK's services industry, Brexit will reduce market access and lead to barriers for UK service providers seeking to provide services in the EU.

Whilst both the UK and the EU have committed to comprehensive, close, balanced and reciprocal law enforcement and judicial co-operation in criminal matters there is little clarity about how that can be achieved given` the UK will no longer be a Member State.

Context

After the UK leaves the European Union on 31 January 2020 attention will turn to the negotiation of the future relationship between the EU and the UK.

The Political Declaration on the future relationship

Whilst the Political Declaration on the future relationship has no legal basis, it provides a useful indicator of the likely direction for discussions between the UK and the EU.

The Political Declaration covers the following areas:

Part I - initial provisions.

Part II - economic partnership.

Part III - security partnership.

Part IV - institutional and other horizontal arrangements.

Part V - forward process.

The economic partnership section covers ambitions for a Free Trade Agreement and provides details on the approach for goods, services, mobility arrangements, transport, energy, fishing opportunities, global co-operation and level playing field provisions.

The security partnership section covers joint ambitions for co-operation in criminal matters, foreign policy, security and defence.

The institutional arrangements section describes a joint desire for an overarching framework for governance, which could take the form of an Association Agreement. This includes mechanisms for dialogue, strategic direction and dispute resolution.

We provide further information on Parts II and III in more detail below.

The economic partnership sets out the following ambitions:

Creation of a Free Trade Agreement with no tariffs and quotas.

Recognition of rules of origin as a result of there no longer being a single UK-EU customs territory.

Provisions to promote regulatory approaches that are "transparent, efficient, promote avoidance of unnecessary barriers to trade in goods and are compatible to the extent possible".

Potential for UK authorities' cooperation with Union agencies such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).

Potential for UK participation in EU funding programmes.

Comprehensive and balanced arrangements on trade in services and investment in services and non-services sectors, respecting each Party's right to regulate.

Attempt to reach agreement that each parties regime for financial services can be recognised as equivalent allowing close cooperation on financial services.

These issues are discussed in more detail in the section on key areas of negotiations from a Scottish perspective.

The security partnership

The Security Partnership section of the Political Declaration indicates that the UK and EU should establish a "broad, comprehensive and balanced security partnership" which:

will take into account geographic proximity and evolving threats, including serious international crime, terrorism, cyber-attacks, disinformation campaigns, hybrid threats, the erosion of the rules-based international order and the resurgence of state-based threats.

The only significant amendment from the 2018 version of the Political Declaration is the removal of the explicit reference in paragraph 81 to the role of the Court of Justice of the European Union (European Court of Justice) in the resolution of disputes on law enforcement and criminal justice cooperation.

Instead, the general rules on dispute resolution in paragraphs 129-132 of the Political Declaration will apply. These provide for resolution through an independent arbitration panel if disputes cannot be resolved informally or through the Joint Committee (a body made up of EU and UK representatives). The arbitration panel's decisions are binding. However, the panel has to refer questions on the interpretation of EU law to the European Court of Justice which can itself make binding rulings on such matters.

The European Court of Justice will therefore continue to have a role when it comes to the application of EU law to the security partnership.

The process for negotiating the future relationship

The EU's approach to negotiating agreements with third parties is guided by the Treaties and as a result the EU is subject to tight legal restraints.

There is little detail about the UK Government's intended approach to the negotiations. The provisions of the original Withdrawal Agreement Bill had made reference to a role for the UK Parliament, however, these provisions were removed in the new European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill which was introduced in the House of Commons on 19 December 2019.

The EU approach

The EU's legal infrastructure will guide the process and present challenges in terms of how an agreement is reached and ratified. Article 218 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) sets out the procedure for the EU's negotiation of international agreements with third countries (the Institute for Government has produced a useful explainer). The process set out in Article 218 is highlighted in the Political Declaration as the process by which the future relationship negotiations should be conducted. In terms of getting agreement on the future relationship two factors are worth considering:

how the final deal is agreed at EU level

whether member state ratification is required.

Article 218(8) states that any agreement will be achieved by a qualified majority vote of the Council. This means that 72% of the 27 EU member states (representing at least 65% of the total population of the 27 EU member states) need to vote in favour of the agreement.

However, Article 218(8) adds that the Council must act unanimously when the “agreement covers a field for which unanimity is required for the adoption of a Union act, as well as for association agreements”. In addition, Article 207(4) provides that negotiations under Article 218 where they include the fields of trade in services, the commercial aspects of intellectual property and foreign direct investment should also require unanimous agreement in the Council.

In most cases any agreement also requires the consent of the European Parliament.

In a briefing for the Scottish Parliament's Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee, Professor Tobias Lock outlined the key constraints on the EU as being competence and procedural constraints.

On competence, Professor Lock wrote that:

The main constraint stems from the fact that the EU is not a sovereign entity, but that it only possesses those competences that the Member States have conferred upon it. This means that its powers to conclude international agreements are limited to certain policy areas.

Lock, T. (2017, December 20). The legal and political process for agreeing the future relationship between the EU and the UK and any transitional arrangement. Retrieved from https://parliament.scot/S5_European/General%20Documents/CTEER_2017.12.20_Research_paper_Tobias_Lock_Published.pdf [accessed 3 December 2019]

On procedural constraints, Professor Lock set out the requirements in relation to finalising any agreement. This requires either unanimity or qualified majority support in the Council, and potentially the consent of the European Parliament:

EU agreements are generally concluded by the Council – i.e. the relevant ministers of the Member States. Depending on the type of agreement concluded, the Council must either agree unanimously or by qualified majority. Furthermore, the EU Treaties sometimes require the European Parliament’s consent, sometimes mere consultation of the European Parliament, and in some cases no involvement of the European Parliament.

The key point made by Professor Lock is that if an agreement that covers both EU and member state competences is concluded (a so-called mixed agreement) then ratification will be required not just at EU level but also by all 27 EU member states in line with their own constitutional requirements. This means it might require not just national parliamentary approvals but in some cases the approval of some regional parliaments - the example of the Walloon Parliament and the EU-Canada deal is often cited. Logically, Professor Lock concludes that:

Mixed agreements are therefore more time-consuming to conclude and encounter more potential hurdles. The EU cannot choose to ignore these constraints. Not only would this run counter to its self-understanding as being founded on the basis of the rule of law, but it would also make any agreement concluded in violation of these limits liable to being declared incompatible with the Treaties – and thus invalid – by the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

Key players

On 22 October 2019, the European Commission announced that a new ‘Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom’ (UKTF) was to be established. Michel Barnier was appointed as Head of the Task Force with responsibility to oversee negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK1. Barnier led the Commission's Article 50 Task Force negotiating the terms of the UK's departure from the EU. The role of the UKTF will be to continue the European Commission's Brexit related work:

The UKTF will include the current TF50 ('Task Force for the Preparation and the Conduct of the Negotiations with the United Kingdom under Article 50 TEU') and the Secretariat-General's ‘Brexit Preparedness' unit. The Task Force, just like TF50, will coordinate all the Commission's work on all strategic, operational, legal and financial issues related to Brexit. It will be in charge of the finalisation of the Article 50 negotiations, as well as the Commission's ‘no-deal' preparedness work and the future relationship negotiations with the UK. It will operate under the direct authority of the President and in close cooperation with the Secretariat-General and all Commission services concerned.

European Commission. (n.d.) Daily News. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEX_19_6146 [accessed 5 December 2019]

Michel Barnier will be expected to work closely with the new Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, new Council President, Charles Michel, and the 27 Heads of State and Government represented in the European Council.

Adding further continuity, Sabine Weyand - Michel Barnier’s deputy during the Article 50 negotiations - is now the head of the European Commission’s directorate general for trade, meaning she will also play a role in the future relationship discussions with the UK.

EU priorities for the negotiations

The European Commission is yet to publish a draft mandate for negotiations to the European Council, to the Council of Ministers and to the European Parliament. Michel Barnier, has indicated that the European Commission hopes to propose the negotiating mandate by 1 February with the negotiations being launched towards the end of February or early March with the aim of "making as much progress as possible by June"1 when EU27 and UK leaders will meet to take stock of the negotiations.

In a speech at the London School of Economics on 8 January 2020, the Commission President Ursula von der Leyen was clear that the depth of the future relationship will be dictated by the UK Government's decision to end free movement and dependent on the UK Government's approach to level playing field provisions:

But the truth is that our partnership cannot and will not be the same as before. And it cannot and will not be as close as before – because with every choice comes a consequence. With every decision comes a trade-off. Without the free movement of people, you cannot have the free movement of capital, goods and services. Without a level playing field on environment, labour, taxation and state aid, you cannot have the highest quality access to the world's largest single market.

The more divergence there is, the more distant the partnership has to be.

European Commission. (2020, January 8). Speech by President von der Leyen at the London School of Economics on 'Old friends, new beginnings: building another future for the EU-UK partnership'. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_20_3 [accessed 13 January 2020]

The Commission President also suggested that the UK Government's insistence on not extending the transition period beyond the end of 2020 would mean that the negotiations would have to focus on a number of priorities and that an all-encompassing future relationship might not be possible in the eleven months available. Given these limitations and the EU's determination to protect the integrity of the Single Market and the Customs Union, Ursula von der Leyen set out the EU's priorities for the negotiations:

But we are ready to design a new partnership with zero tariffs, zero quotas, zero dumping. A partnership that goes well beyond trade and is unprecedented in scope. Everything from climate action to data protection, fisheries to energy, transport to space, financial services to security. And we are ready to work day and night to get as much of this done within the timeframe we have.

European Commission. (2020, January 8). Speech by President von der Leyen at the London School of Economics on 'Old friends, new beginnings: building another future for the EU-UK partnership'. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_20_3 [accessed 13 January 2020]

The European Commission also highlighted the importance of a continued security partnership after the UK has left the EU. Highlighting terror attacks in the UK and across the EU, she said:

And we must ensure that we continue to work together on upholding peace and security in Europe and around the world. We must build a new, comprehensive security partnership to fight cross-border threats, ranging from terrorism to cyber-security to counter-intelligence. Events in recent years in Salisbury, Manchester, London and right across Europe have underlined the need for us to work together on our mutual security.

The threat of terrorism is real and we have to share the necessary information and intelligence between Europe and the UK to stop terrorists from crossing borders and attacking our way of life.

European Commission. (2020, January 8). Speech by President von der Leyen at the London School of Economics on 'Old friends, new beginnings: building another future for the EU-UK partnership'. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_20_3 [accessed 13 January 2020]

Following Ursula von der Leyen's visit to London, Michel Barnier, spoke at the European Commission representation in Stockholm. He highlighted that the time to negotiate the future relationship (eleven months) would be "hugely challenging" if the UK Government chose not to request an extension to the transition period. On the kind of future relationship the EU will seek.Barnier said:

We will strive for a partnership that goes well beyond trade and is unprecedented in scope: covering everything from services and fisheries, to climate action, energy, transport, space, security and defence.

But that is a huge agenda. And we simply cannot expect to agree on every single aspect of this new partnership in under a year.

European Commission. (2020, January 9). Remarks by Michel Barnier at the European Commission Representation in Sweden. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_13 [accessed 13 January 2020]

Reflecting on the potential time available for the negotiations and the ambitions set out in the Political Declaration, Barnier continued:

The Political Declaration is much easier to read: 36 pages, very concise, covering all aspects of the future relationship – the ones we agreed together.

If we want to agree on each and every point of this Political Declaration – which would lead to an unprecedented relationship – it will take more than 11 months.

European Commission. (2020, January 9). Remarks by Michel Barnier at the European Commission Representation in Sweden. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_13 [accessed 13 January 2020]

Barnier reiterated the EU's priorities as set out in the Political Declaration - security and an economic partnership making clear that the economic partnership will be "subject to a level playing field on environmental and social standards, state aid and tax matters"1.

Finally, he said that he believed that the cost of an economic no-deal at the end of 2020 would be more damaging to the UK than to the EU:

Yes, the UK represents 9% of all EU27 trade.

But more significantly, the EU27 accounts for 43% of all UK exports and 50% of its imports.

So, it is clear that if we fail to reach a deal, it will be more harmful for the UK than for the EU27.

All the more so because EU Member States can rely on each other or on the many other partners that the EU has free trade agreements with.

So we will insist on a trade partnership with zero tariffs, zero quotas, but also zero dumping.

European Commission. (2020, January 9). Remarks by Michel Barnier at the European Commission Representation in Sweden. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_13 [accessed 13 January 2020]

The UK approach

The previous version of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill included clauses proposing powers for the UK Parliament in terms of approving any extension of the implementation period and in approving the UK Government's negotiating mandate for the future relationship. Both of these provisions have been removed from the new Bill. This may result in the UK Parliament facing a challenge in being able to both scrutinise and influence the nature of the future relationship negotiations. This is in stark contrast to the role that the European Parliament has in overseeing the EU's approach to third country negotiations. On a parliamentary role in the negotiations, the Institute for Government has argued that:

It is far from clear what role, if any, the government now envisages for Parliament. By sidelining Parliament, the government has greater flexibility in terms of when to start the negotiations – but ministers still need to think about how to update MPs during the talks.

Institute for Government. (2020, January 10). Getting Brexit done What happens now?. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/getting-brexit-done_0.pdf [accessed 13 January 2020]

There is no role in the negotiations on the future UK-EU relationship for the Scottish Parliament or Scottish Government set out in the Withdrawal Agreement Bill.

Key players

The Prime Minister will have to decide which UK Government Department is to lead the negotiations – options include the Department for Exiting the EU (which may be wound up after 31 January 2020); the Department for International Trade or the Cabinet Office. It is likely that the Prime Minister’s Chief Adviser on Brexit, David Frost will play a key role.

The UK Government has yet to set out a process for conducting the negotiations or said whether it anticipates a role for devolved bodies.

UK priorities for the negotiations

The Conservative Party manifesto ahead of the December 2019 General Election provided little detail about the future UK-EU relationship, stating that:

Our deal is the only one on the table. It is signed, sealed and ready. It puts the whole country on a path to a new free trade agreement with the EU. This will be a new relationship based on free trade and friendly cooperation, not on the EU’s treaties or EU law. There will be no political alignment with the EU. We will keep the UK out of the single market, out of any form of customs union, and end the role of the European Court of Justice.

This future relationship will be one that allows us to:

Conservative Party. (n.d.) Conservative Manifesto 2019. Retrieved from https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan/get-brexit-done-and-unleash-britains-potential [accessed 16 December 2019]

Take back control of our laws.

Take back control of our money.

Control our own trade policy.

Introduce an Australian-style points-based immigration system.

Raise standards in areas like workers’ rights, animal welfare, agriculture and the environment.

Ensure we are in full control of our fishing waters.

The manifesto essentially reiterated the content of the Political Declaration.

The Prime Minister met European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in London on 8 January 2020. According to the UK Government's readout of the meeting:

On Brexit, the PM stressed that his immediate priority was to implement the Withdrawal Agreement by January 31. They discussed the progress of ratification in the UK and in the European Parliament.

He said the UK wanted a positive new UK and EU partnership, based on friendly cooperation, our shared history, interests and values.

The PM reiterated that we wanted a broad free trade agreement covering goods and services, and cooperation in other areas.

The PM was clear that the UK would not extend the Implementation Period beyond 31 December 2020; and that any future partnership must not involve any kind of alignment or ECJ jurisdiction. He said the UK would also maintain control of UK fishing waters and our immigration system.

The PM made clear that we would continue to ensure high standards in the UK in areas like workers’ rights, animal welfare, agriculture and the environment.

UK Government. (2020, January 8). PM meeting with EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen: 8 January 2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-meeting-with-eu-commission-president-ursula-von-der-leyen-8-january-2020 [accessed 13 January 2020]

Ahead of the the UK Government’s negotiation of a new relationship with the EU , it is not clear whether there will be discussion within the UK about what the country wishes to prioritise and achieve from the future relationship negotiations. On 10 January 2020, the Institute for Government published Getting Brexit done What happens now? In the paper, the IfG suggested that the UK Government needed to agree its priorities in the negotiations adding that:

But it is far from clear how much detailed thought the Johnson administration has given to what it wants from Great Britain’s relationship with the EU...

...An immediate task for the new government will be revisiting that work on the future UK–EU relationship, before reaching collective agreement within the Cabinet on the detailed negotiating objectives.

Institute for Government. (2020, January 10). Getting Brexit done What happens now?. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/getting-brexit-done_0.pdf [accessed 13 January 2020]

When the negotiations begin, the UK will face the challenge of trying to achieve its objectives of securing a free trade agreement in the time available whilst protecting its red lines. However, as the BBC’s Europe Editor Katya Adler has said, the EU is unlikely to agree to a free trade deal without obtaining concessions on level playing field regulations and securing EU fishing rights in UK waters.

Timing for the negotiations

The December 2019 European Council meeting conclusions set out the EU's intention to begin discussions with the UK Government as soon as possible and requested that the European Commission present a draft negotiating mandate for the European Council's consideration.

A key element which may influence the future negotiations is the restriction on the timescale to make a request to extend the transition period beyond the end of 2020. The Withdrawal Agreement provides for the Joint Committee to agree an extension of the transition period for up to one or two years but states that a decision on extending the period must be taken by 1 July 2020. As a result, there is very limited time to agree a new relationship before the implementation period ends or for a decision to be made about extending it.

In its election manifesto, the Conservative Party stated it would not extend the transition period beyond the end of 2020:

We will negotiate a trade agreement next year – one that will strengthen our Union – and we will not extend the implementation period beyond December 2020.

Conservative Party. (n.d.) Conservative Manifesto 2019. Retrieved from https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan/get-brexit-done-and-unleash-britains-potential [accessed 16 December 2019]

Clause 33 of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill provides that a UK Minister "may not agree in the Joint Committee to an extension of the implementation period". As a result, this would set down in UK law that the UK would exit the implementation period at the end of December 2020. In the event the UK Government fails to conclude its desired future relationship with the EU before the end of December 2020, the country will once again face an effective no-deal situation (in relation to trade in goods and services). At this point, however, the UK would not be a member of the EU and there is no clear and obvious way to delay such a no-deal scenario as was possible when seeking three extensions to the Article 50 process in 2019. Speaking in the House of Commons debate on the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, the Steve Barclay, the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU referred to the length of the implementation period:

Both the EU and the UK committed to a deal by the end of 2020 in the political declaration. Now, with absolute clarity on the timetable to which we are working, the UK and the EU will be able to get on with it. In sum, clause 33 will ensure that we meet the timetable set out in the political declaration and deliver on our manifesto promise.

UK Parliament. (2020, January 7). House of Commons Hansard European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill. Retrieved from https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2020-01-07/debates/C5ADC5C3-0008-4CBB-81D6-717666FC7C4B/EuropeanUnion(WithdrawalAgreement)Bill [accessed 16 January 2020]

Professor Anand Menon and Jill Rutter writing for the UK in a Changing Europe blog have suggested that they doubt agreeing a new relationship before the end of 2020 is achievable:

The refusal to countenance an extension beyond December 2020 means they are putting themselves — and the EU — under tremendous pressure to agree and sign-off a trade deal by that date.

We doubt whether this is achievable. The EU is concerned not about where the UK is starting from but where it wants to go: it will insist ambitions for on some level playing field conditions even for a bare-bones deal on goods.

Menon, A., & Rutter, J. (2019, December 5). Neither the Tories nor Labour are offering credible promises on Brexit. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/neither-the-tories-nor-labour-are-offering-credible-promises-on-brexit/ [accessed 5 December 2019]

Sir Ivan Rogers, formerly the Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the European Union has suggested that the limited time to reach an agreement means the UK Government may need to accept a sub-optimal deal to ensure the UK doesn't leave the transition period at the end of 2020 without having the terms of a new trading relationship in place. In a speech at Glasgow University, Sir Ivan Rogers said:

The major threat for the UK as I see it, is therefore not that nothing at all gets done next year.

But that, because we are under immense time pressure, and known to be desperate to “escape vassalage” by the end of 2020 – something to which the Prime Minister daily keeps committing, and the Tory manifesto commits – the EU side just sees a huge open goal opportunity and repeats its playbook from the Article 50 process.

After all, it thinks it worked really rather well. It's rather hard to argue that tactically it didn't…

So it entirely dictates the contents and pace of what does get done, runs the clock down towards the next cliff edge, and confronts a desperate UK Prime Minister with a binary choice between a highly asymmetrical thin deal on its terms, and “no deal” towards the end of next year. If all the time pressure is on him, you can safely assume he will make a lot of concessions in the endgame, and yet still have to emerge blinking into the light claiming victory.

If the EU can then button down in legally binding form what it feels it most needs out of a deal on that timescale, then it may feel “job done”: its members are scarcely going to want to have to negotiate, then ratify a whole series of further deals with the UK thereafter, if they feel their key objectives have already been secured.

Rogers, I. (2019, November 25). The Ghost of Christmas yet to come: Sir Ivan Rogers’ Brexit lecture – video and full text. Retrieved from https://policyscotland.gla.ac.uk/ghost-of-christmas-yet-to-come-brexit-lecture-full-text/ [accessed 5 December 2019]

Role for the devolved administrations and legislatures in the future relationship negotiations

The Scotland Act (as with the Acts in relation to Wales and Northern Ireland) specifically reserves foreign affairs and international relations, including relations with territories outside the United Kingdom, whilst not reserving observing and implementing international obligations. Given the likely breadth of any future relationship negotiated with the EU, it is likely to include obligations in devolved policy areas.

The Institute for Government has argued that "the UK government must involve the devolved administrations to properly reflect Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish interests in the talks" writing:

Many of the areas included in the future relationship negotiations will have direct implications for devolved competencies. Decisions made in Westminster will constrain devolved activity, in particular in terms of agriculture, fisheries and any level playing field commitments on the environment.

The devolved administrations will also be responsible for implementing parts of the future trade agreement, and any legislation implementing a new UK–EU trade deal will almost certainly require the consent of the devolved legislatures. A failure to actively involve the devolved administrations throughout the next phase of negotiations will increase the risk of practical and political fallout when a deal is brought back from Brussels.

Institute for Government. (2020, January 10). Getting Brexit done What happens now?. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/getting-brexit-done_0.pdf [accessed 13 January 2020]

SPICe has previously published a briefing on the Negotiation of Trade Agreements in Federal Countries. This examined the representation and influence of provinces/regions/states in federal countries in the negotiation and implementation of trade agreements.

At this stage, no role has been set out for the UK's devolved administrations and legislatures in the UK-EU future relationship negotiations. As then Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, David Lidington made a written statement to the House of Commons in July 2018 on "Engaging the Devolved Administrations". In it he set out the then UK Government's approach to ensuring the views of all four nations of the UK are represented in the Brexit negotiations:

It is imperative that, as the United Kingdom prepares to leave the EU, the needs and interests of each nation are considered and that the UK Government and devolved administrations benefit from a unified approach wherever possible. That is only possible through the strength of our relationships and continued constructive engagement through a number of fora at ministerial and official level.

UK Parliament. (2018, July 23). Engaging the devolved administrations:Written statement. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-statement/Commons/2018-07-23/HCWS905/ [accessed 5 December 2019]

The Minister also referred to the establishment of the intergovernmental Ministerial Forum (EU Negotiations) which first met in Edinburgh on 24 May 2018 and whose immediate task was to consider "the White Paper on the Framework for the UK’s Future Relationship with the EU"3. The Ministerial Forum (EU Negotiations) appears to have met eight times, most recently on 25 February 2019 in Cardiff. On the agenda that day was " a discussion on the role of the Ministerial Forum in the next phase of negotiations"4. However, since that meeting there appears to have been no further meetings of the Ministerial Forum. The other Brexit related intergovernmental group, the Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) met for the 21st time on 9 January 2020. Meeting in London, the Committee's discussions included "the UK’s exit from the EU, including preparations for the UK-EU future relationship negotiations and a forward look to post-January engagement structures".5

The intergovernmental discussions which take place under the guise of the Joint Ministerial Committees result in very little detailed information being made public following the meetings making scrutiny of the roles of each of the administrations by their respective legislatures very challenging. If information on the negotiation of the future relationship is shared in the Joint Ministerial Committees, this will present a challenge to the devolved legislatures in particular in scrutinising the negotiations.

Giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament's Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee on 31 October 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations, Michael Russell spoke about the level of devolved administration input into the Brexit negotiations and in particular the consequences for devolved competences of the negotiations for the future relationship:

We have had enormous difficulty getting the UK to the table on this issue. The Johnson Government has added an extra dimension. We had an agreement with the previous Government at the British-Irish Council in Manchester in June. In the margins of that, we had a JMC meeting, where we finally agreed a timetable. We agreed that, by the end of September, we would have the initial outline of what should happen and that the work should be finished by the end of the year. That is not going to happen. We have not had the initial outline—we have still not seen anything, and it is almost November. In my view, there is no point in having that conversation in November, because the election will take precedence, and what will happen on this matter will be guided by what happens in the election.

There is a potential solution, which is to recognise that the detailed negotiations will involve devolved competencies. You could theoretically argue that the withdrawal agreement and the political direction do not involve devolved competencies. I disagree with that, but you could argue that they are covered entirely by the international relations reservation. The fact that the UK Government has had to seek legislative consent for the withdrawal agreement bill rather gives the lie to that, but that is in the past.

Scottish Parliament Official Report. (2019, October 31). Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee 31 October 2019. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12337 [accessed 5 December 2019]

The Cabinet Secretary reiterated the Scottish Government's belief that "where there are devolved competences, the decision on those devolved competences must be made by the devolved administrations, not by anybody else". He cited Philip Rycroft, former Permanent Secretary, Department for Exiting the EU who told the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee on 29 October 2019 that for the future relationship negotiations:

For my part, the learning from the previous phase is to draw the devolved Governments into the process early, and share the thinking on the UK Government position so you develop common negotiating positions that the devolved Administrations can get locked in behind. They can promote the UK’s overall position along with the UK Government, giving us a far greater chance of succeeding in delivering the negotiating aims. Transparency is the key.

UK Parliament. (2019, October 29). House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/foreign-affairs-committee/the-future-of-britains-diplomatic-relationship-with-europe-follow-up/oral/106809.html [accessed 5 December 2019]

UK Government proposed policy approach to international negotiations

Whilst there is no formal process set out for how the devolved administrations and legislatures might be involved in the future relationship negotiations, it is helpful to look at relevant policy documents published by the UK and Scottish Governments.

In the new policy paper on devolution in Northern Ireland, New Decade New Approach published in January 2020, the UK Government has committed to "to consulting a restored [Northern Ireland] Executive along with the other devolved administrations on our wider trade policy"1.

On 28 February 2019, the UK Government published "Processes for making free trade agreements once the UK has left the EU". The paper set out the UK Government's proposals for how the UK will agree future trade deals with third countries after Brexit. However, the UK Government stated that the proposals do not apply to other international negotiations and treaties, including negotiations on the future relationship with the EU. Despite these processes not applying to the negotiation of the future UK-EU relationship, the paper provides an insight into a potential role for the devolved administrations and legislatures in the next stage of the Brexit process.

From a devolved perspective, the UK Government paper states:

Government is committed to working closely with the devolved administrations to deliver a future trade policy that works for the whole of the UK. It is important that we do this within the context of the current constitutional make-up of the UK, recognising that international treaties are a reserved matter but that the devolved governments have a strong and legitimate interest where they intersect with areas of devolved competence.

UK Government Department for International Trade. (2019, February 28). Processes for making free trade agreements after the United Kingdom has left the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/782176/command-paper-scrutiny-transparency-27012019.pdf [accessed 5 December 2019]

On the role of the devolved legislatures, the UK Government wrote:

We recognise that the devolved legislatures also have a strong and legitimate interest in future trade agreements. It will be for each devolved legislature to determine how it will scrutinise their respective Governments as part of the ongoing process. Equally, the means by which our Parliament in Westminster works with its devolved counterparts is a matter for the legislatures themselves, in line with their existing inter-parliamentary ways of working.

UK Government Department for International Trade. (2019, February 28). Processes for making free trade agreements after the United Kingdom has left the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/782176/command-paper-scrutiny-transparency-27012019.pdf [accessed 5 December 2019]

Scottish Government proposed policy approach to international negotiations

Ahead of the UK Government's publication, the Scottish Government published "Scotland's role in the development of future UK trade arrangements" on 30 August 2018. The Scottish Government outlined the key conclusion of the document:

Outside the Customs Union, the UK will become responsible for negotiating its own international trade agreements. The broad and increasing scope of modern trade agreements means that they often deal with, and merge, a range of reserved and devolved policy areas. The conduct and content of future trade policy, negotiations and agreements will therefore have very important implications for Scotland, and it is vital that the Scottish Government is fully involved in the process for determining them.

This paper considers that decision making process and argues that the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament must play a much enhanced role in the development of future trade policy and the preparation, negotiation, agreement, ratification and implementation of future trade deals, to help industries, protect devolved public services and ensure the highest standards of environmental and consumer protection in Scotland and across the UK. Doing so will require a significant change in the current arrangements for scrutiny and democratic engagement, which are already out of date, under strain and in urgent need of reform.

Scottish Government. (2018, August 30). Scotland's role in the development of future UK trade arrangements. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-role-development-future-uk-trade-arrangments/ [accessed 5 December 2019]

In terms of parliamentary scrutiny of future trade negotiations and agreements, the Scottish Government's paper suggests that the current arrangements for scrutiny of trade agreements at Westminster (based on the provisions of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010) are limited. This is because the UK Parliament does not have to debate or vote on ratification and has no power to amend a treaty or be involved in treaty negotiation.

In terms of the role of devolved legislatures in the negotiation and ratification of trade agreements, the Scottish Government wrote:

There is not currently, and nor is there proposed to be, any legal requirement to consult the devolved administrations and legislatures, stakeholders or the public. The MoU and Concordats provide the only articulation at present of Scotland's rights and responsibilities in protecting and promoting its interests in the field of international relations and international trade.

Scottish Government. (2018, August 30). Scotland's role in the development of future UK trade arrangements. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-role-development-future-uk-trade-arrangments/ [accessed 5 December 2019]

The Scottish Government concluded that both it and the Scottish Parliament must have a role in "all stages of the formulation, negotiation, agreement and implementation of future trade deals and future trade policy".

In July 2019, the Scottish and Welsh First Ministers wrote to the Prime Minister to demand a commitment to full involvement of the devolved administrations in international negotiations which impact on devolved competence. The letter stated:

We need a commitment to full involvement of the devolved administrations in international negotiations which impact on devolved competence. If we leave the European Union, we will need to renegotiate the United Kingdom’s relationship with the European Union institutions and the rest of the world. The interests and responsibilities of the devolved institutions and governments will be affected, directly and indirectly. The devolved institutions and governments also have knowledge and expertise to contribute to the UK’s negotiating efforts. The former Chancellor for the Duchy of Lancaster recognised the need for the UK Government to agree an enhanced role for the devolved institutions and governments in any such discussions and decisions. We seek an early commitment from you to do just that, without prejudice to the full completion of the IGR Review. The Scottish and Welsh Governments and our Parliaments cannot be expected to co-operate on implementing obligations in devolved areas where we have not been fully involved in the determination of those obligations.

Scottish Government. (2019, July 25). First Ministers of Scotland and Wales call on new Prime Minister to rule out ‘no deal’ Brexit. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/news/first-ministers-of-scotland-and-wales-call-on-new-prime-minister-to-rule-out-no-deal-brexit/ [accessed 9 December 2019]

What's happened so far?

Up to now, in preparation for Brexit, the UK Department for International Trade (DIT) has been mostly engaged in the so-called Trade Agreement Continuity Programme.1 That is, the focus has been on "rolling-over" existing agreements with third countries to which the UK is a party through the EU, to ensure continuity of trade with these countries. Formal negotiation with other countries that have no deal with the EU (Australia, US, India, China) is not at an advanced stage and will probably begin in earnest after Brexit.

Therefore, while not directly relevant to the UK-EU future trade relationship, the negotiating practice with respect to "roll-over" agreements can be assessed, to gauge the level of involvement of the devolved administrations. The Department for International Trade, in the Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the agreement between the UK and Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, has described in general terms a practice of informing the devolved administrations of any progress made. There is no suggestion that this interaction entailed any active role of the devolved administrations in the negotiation of the treaty.

International relations including the making of treaties is not devolved. However, as there is likely to be significant impact on Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the Government has regularly updated the Devolved Administrations and has shared the texts of parliamentary reports and explanatory memorandums with them.

Throughout the Trade Agreement Continuity Programme, DIT has engaged with the Devolved Administrations (DAs). Both Ministers and officials speak to counterparts in the DAs on a regular basis, sharing progress and inviting them to highlight agreements of importance or concern.

DIT can confirm that the text of agreements, once stable, are shared with DAs; DIT has also offered briefings on the agreements, where appropriate, on request to DAs, Crown Dependencies and Gibraltar. DIT shares draft Parliamentary Reports and Explanatory Memoranda on individual agreements, and DIT welcomes DAs’ views as progress is made.

UK Government, Department for International Trade. (2019, June 14). Explanatory Memorandum on the Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, of the one part, and the Republic of Colombia, the Republic of Ecuador, and the Republic of Peru, of the other part. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/808915/EM_MS_22.2019_Andean_Trade.odt [accessed 4 January 2020]

It appears that the content of the agreements is shared not during the negotiations, but only when the text is “stable,” i.e. finalised. It also seems that the burden is on devolved administration to "request" information. Other explanatory memos use marginally different language, but convey the same impression. In relation to the Association deal with Lebanon, for instance, the DIT stated:

HMG shares stable agreement texts, draft Parliamentary Reports and Explanatory Memoranda on individual agreements, and HMG welcomes the views of the DAs, the Crown Dependencies and Gibraltar as progress is made.

UK Government, Department for International Trade. (2019, October 22). Explanatory Memorandum on the Agreement establishing an Association between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Republic of Lebanon. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/840964/EM_CS_Lebanon_1.2019_Agreement_establishing_an_Association_between_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_and_the_Republic_of_Lebanon.odt [accessed 4 January 2020]

It must be noted, however, that the negotiation of "roll-over" treaties is a poor comparator for the negotiation of future trade treaties (both with the EU and third countries that have no deal with the EU). Because "roll-over" treaties only aim to secure trade continuity with the partner countries, their content is almost exclusively a replica of the EU agreements with them. Instead, the content of a future UK-EU agreement must be defined through negotiation between the parties.

The limited involvement of devolved administrations in the Trade Continuity Programme could be premised on, or justified by, the assumption that the content of the "roll-over" treaties is pre-established. Instead, the range of policy choices and trade-offs that the DIT will have to make to reach a deal with the EU is such that devolved administrations will demand to play an active role in shaping its content.

Key areas of negotiation from a Scottish perspective

Level playing field and regulatory alignment

Fisheries

Food and drink and PGIs

Agriculture

Services

Justice and Security

Immigration/Mobility

EU funding programmes

Level playing field and regulatory alignment

Under the first Withdrawal Agreement the Northern Ireland backstop would have created a single customs territory between the EU and the UK. To facilitate this the Ireland and Northern Ireland Protocol created a set of arrangements designed to ensure that the regulatory environments in the UK and EU custom territories were similar in some respects - this is referred to as the "level playing field". These arrangements set out to prevent companies benefiting from an unfair competitive advantage by virtue of being in a single customs territory but under different tax and regulatory regimes. This "advantage" would typically be gained due to the lowering or non-enforcement of regulatory standards or as a result of different taxation or state aid practices.

Level playing field areas covered in the Protocol included environmental protections, labour standards and State Aid. As a result of the removal of the Northern Ireland backstop - to be replaced by a permanent arrangement involving Northern Ireland only - the level playing field measures which were included in the first Withdrawal Agreement have been removed.

Section XIV of the Political Declaration now references the level-playing field provisions in a less specific way. Section XIV states:

Given the Union and the United Kingdom's geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the future relationship must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field. The precise nature of commitments should be commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship and the economic connectedness of the Parties. These commitments should prevent distortions of trade and unfair competitive advantages. To that end, the Parties should uphold the common high standards applicable in the Union and the United Kingdom at the end of the transition period in the areas of state aid, competition, social and employment standards, environment, climate change, and relevant tax matters. The Parties should in particular maintain a robust and comprehensive framework for competition and state aid control that prevents undue distortion of trade and competition; commit to the principles of good governance in the area of taxation and to the curbing of harmful tax practices; and maintain environmental, social and employment standards at the current high levels provided by the existing common standards. In so doing, they should rely on appropriate and relevant Union and international standards, and include appropriate mechanisms to ensure effective implementation domestically, enforcement and dispute settlement. The future relationship should also promote adherence to and effective implementation of relevant internationally agreed principles and rules in these domains, including the Paris Agreement.

UK Government. (2019, October 19). New Political Declaration. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/840656/Political_Declaration_setting_out_the_framework_for_the_future_relationship_between_the_European_Union_and_the_United_Kingdom.pdf [accessed 5 December 2019]

On 14 January 2020, the European Commission published slides on the level playing field issues likely to be at play during the future relationship negotiations. The slides set out the Commission's approach to the negotiations on level playing fields would be based on the overarching principle that:

Given the Union and the United Kingdom’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the future relationship must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field.

European Commission. (2020, January 14). Internal EU27 preparatory discussions on the future relationship: "Level playing field". Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/seminar-20200114-lpf_en.pdf [accessed 15 January 2020]

Leading from this, the Commission set out the objective of achieving common approaches in the fields of State Aid to prevent undue distortion of trade and competition along with measures on good governance in the area of taxation. In the areas of environmental policy and workers rights the Commission stated that the UK and EU should seek to:

maintain environmental, social and employment standards at the current high levels provided by the existing common standards

European Commission, Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom. (2020, January 13). Internal EU27 preparatory discussions on the future relationship: "Free trade agreement". Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/seminar-20200113-fta_en_0.pdf [accessed 14 January 2020]

If the UK Government agrees to the level playing field commitments likely to be requested by the EU, it should mean a closer trading relationship is possible between the two parties. Whilst the Devolved Administrations are likely to welcome this closer trading relationship, it is likely to also means the UK Government would be making regulatory commitments in devolved areas such as environmental or animal welfare standards. As such, the Scottish Government will have an interest in how the UK Government approaches the level playing field question in the negotiations.

On the other hand, if the UK Government wishes to conclude ambitious trade agreements with other partners (for example the United States) it may feel less able to commit to the level playing field requirements being proposed by the European Commission. As with any proposal for close regulatory alignment with the EU (for the purpose of allowing the UK better access to the EU market), provisions in this area may limit the scope of the UK's ability to conclude trade deals with other partners. In addition, whatever relationship is agreed, UK goods being sold into the EU will need to continue to comply with EU standards.

Agriculture

The Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) provides a policy framework for EU member states and has therefore set the direction for the UK nations' agriculture policies since the UK joined the EU in 1973. Within the UK context, agriculture policy is devolved, and the Scottish Government is therefore free to design and implement a Scottish agriculture policy under the shared EU framework. As a result of the CAP, UK nations have in common with each other, and share with the EU, the following:

A common subsidy regime. EU regulations determine the amounts that can be paid by member states, the basis for calculating payments, the schemes that must be offered to farmers and the schemes that can be offered on a voluntary basis, and so on.

A common arrangement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Domestic support for agriculture (e.g. subsidies) is subject to WTO agreements which aim to ensure balanced trading arrangements between states. Domestic support is divided into three categories: Amber Box (trade distorting payments, e.g. coupled support for certain sectors), Blue Box (trade distorting payments that also require farmers to limit production) and Green Box (non-trade-distorting payments, e.g. agri-environment payments).1 The EU has agreed maximum levels of support that can be paid out to farmers by EU member states in the Amber Box. However, it is not clear how the UK's share of this allocation will be determined on leaving the EU. Professor Alan Matthews has provided detailed thoughts on future WTO considerations in this blog.

A common regulatory framework. Much of the regulation governing Scottish agriculture originates from the EU. This includes environmental, animal welfare and food safety standards governed by e.g the Nitrates Directive, Birds and Habitats Directives, General Food Law, Hormones Ban Directive, directives on the protection of farmed animals, regulation on plant protection products (pesticides, herbicides and insecticides), and other regulations on public, animal and plant health.2

A common sanction mechanism in cross-compliance. In order to receive EU payments, farmers and crofters must abide by cross-compliance rules. The rules are a combination of statutory management requirements (e.g. the regulations outlined above) and standards for good agricultural and environmental conditions (e.g. good soil management). Cross-compliance adds an additional mechanism to ensure compliance with common standards; failure to meet these can result in not only legal liability, but loss of support payments.2

In addition to, and partly as a result of, the shared policy framework for agriculture, agricultural producers enjoy frictionless and tariff-free trade with the EU. Food and Drink is Scotland's largest export sector4; nearly 40% of Scottish food and drink exports are traded with the EU.4 This is particularly important in certain sectors: 87.7% of UK beef exports went to EU countries in 2018; likewise 95.1% of UK sheep meat exports went to EU countries in 2018, with France being the largest importer.6

Outside the EU, the UK nations will not be subject to the framework of the CAP, and there will be no guaranteed EU funding or common rules for spending it. The UK will need to reach an arrangement with the WTO (and likely with the EU regarding the UK's share of the EU's maximum support allocation). UK nations will no longer automatically be required to ensure regulatory alignment with the EU and nor will they automatically enjoy frictionless and tariff-free trade; this will be subject to any future trading agreements with the EU.

The impact of decisions on the future relationship between the EU and the UK can be split into two categories: regulatory standards; and tariffs and access to markets.

Regulatory standards

Because agriculture is a devolved policy area, when the UK leaves the EU, Scotland may choose, independently of the UK, to set new standards or align with the standards of the EU or a third country; however, this may mean divergence within a UK internal market. As it stands, the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Bill, which is currently being scrutinised by the Scottish Parliament, will give Scotland the flexibility to align itself with either the UK or the EU (or indeed a non-EU country). In giving evidence on the Bill to the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee, Dr George Burgess, Head of Food and Drink at the Scottish Government stated with regards to marketing standards for agricultural products:

If standards diverge because of decisions taken either at European level or by Defra and we have to decide which way to go, the bill will give us the flexibility to do it.

Scottish Parliament. (2019, November 20). Official Report: Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12386

However, while the UK government will be free to set regulatory standards, in reality, future regulatory standards may depend on the trading relationship between the UK and the EU and the influence of agreements with non-EU countries. In particular, new trade agreements with countries with lower standards on animal welfare, the environment or food safety may put Governments under pressure to reduce domestic standards so as not to give imported goods a competitive advantage, while discussions with the EU are likely to emphasise the need for regulatory alignment (see below). There may therefore be a tension between EU and non-EU interests, as well as between the protection and interests of consumers and citizens (including the interest of citizens - from consumers and producers alike - in the protection of animals and the environment) and the economic interests of producers.

Given that 70% of Scotland's land is used for agriculture8, regulatory standards for agriculture are an important part of the body of legislation which protects the environment. As mentioned above, Scottish agriculture is governed by the EU's regulatory rulebook on e.g. the protection of birds and habitats, on protecting watercourses from nitrogen and other pollutants, and on the use of permitted agri-chemicals.2 Likewise, standards for animal welfare, and comprehensive food safety laws govern European agriculture. In particular, European Food Law takes a precautionary approach to protect consumers where the available evidence does not allow for a risk assessment to be made.10 In the establishment of these rules, moreover, institutional capacity exists at EU-level. As Lydgate et al note regarding food safety legislation,

Detaching UK food safety regulation from EU bodies, while maintaining agricultural and food systems that are no less harmful to the environment and public health, is a challenging task. This is because the UK must develop capacities, competencies and procedures that have not been required or available domestically for many years.

Therefore, while leaving the EU may present an opportunity to design bespoke, high Scottish standards that offer protection to people, animals and the environment, there may also be risks to Scotland's environment, and to animal welfare and food safety standards from the ability to unpick regulation, or from a lack of institutional capacity, for which Scotland's devolved institutions have relied on the EU for many years11.

Even from a production point of view, lowering standards may come with risks. It is widely acknowledged that Scottish agriculture is underpinned by quality, and cannot compete on volume and price with other global players.12 James Withers, Chief Executive of Scotland Food and Drink told the Scottish Parliament's Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee on 18 September 2019:

It is important that we do not take an opportunity to unpick the regulatory framework. To some extent, the industry is never a fan of regulation: people round this table will frequently complain about levels of regulation, but the reality is that regulation underpins our brand.

Scottish Parliament. (2019, September 18). Official Report: Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12265

In the UK Parliament, the Scottish Affairs Committee conducted an inquiry into Scotland's priorities for future trade policies post-Brexit. With regards to quality and standards, the Committee's Report emphasised concerns from stakeholders regarding the maintenance of standards:

Tim Allan, President, Scottish Chamber of Commerce, told us this reputation for quality was built on the foundation of EU regulatory standards, which were trusted around the world. He warned that divergence from these could impact on the saleability of products in non-EU markets.

This was echoed by Cat Hay, FDF Scotland, who said international markets such as China were looking for authentic safe products, and by maintaining high standards, there was an opportunity to “capture” the market.

However during this inquiry, we heard concerns that UK standards could be lowered in order to negotiate new free trade agreements with other countries such as the US. This concern has been highlighted in a recent consultation from the US Department of Trade, asking American industry what its objectives would be for a future US-UK Free Trade Agreement. Proposals included:

- The mutual and comprehensive recognition of US food safety and dairy standards, potentially allowing chlorinated chicken and hormone treated beef and milk into the UK;

- The removal of mandatory labelling and traceability requirements for products containing biotech ingredients, allowing genetically-modified food to be sold unlabelled, and

- The removal of the EU’s “precautionary principle” for food and chemical safety, which allows the UK to take a “safety first” approach to regulation and refuse access to the UK market for certain exports which could be dangerous when scientific evidence is uncertain.

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee. (2019, March 7). Scotland, Trade and Brexit. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmscotaf/903/903.pdf [accessed 17 December 2019]

Responding to these concerns during the Committee's inquiry, Dr Michael Gasiorek from theUK Trade Policy Observatory:

argued that protecting consumers and regulating markets should be the primary focus of regulatory policy and that 'changing regulations simply to try become more competitive is probably a really bad principle.'

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee. (2019, March 7). Scotland, Trade and Brexit. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmscotaf/903/903.pdf [accessed 17 December 2019]

Market access and tariffs

The other element of the future relationship with the EU is market access and tariffs on agricultural products. As outlined above, a significant proportion of Scotland's exports go to the EU. Some sectors such as livestock production, which make up 42% of Scotland's agricultural output, are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of losing free trade with the EU.16

The EU have indicated that they are open to free trade on all goods, but only if common standards continue to apply. In an interview with The Guardian and seven other European newspapers, chief Brexit negotiator for the EU, Michel Barnier, clarified the EU's position on market access conditions:

Access to our markets will be proportional to the commitments taken to the common rules...The agreement we are ready to discuss is zero tariffs, zero quotas, zero dumping.

Rankin, J. (29, October 2019). This article is more than 1 month old Michel Barnier tells UK: ignore EU regulatory standards at your peril. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/oct/29/michel-barnier-tells-uk-ignore-eu-regulatory-standards-at-your-peril

From the EU's point of view, therefore, compliance with common regulatory standards as discussed above is inextricably linked to EU market access and the setting of tariffs. Using the example of EU food safety regulation, Lydgate et al. from the UK Trade Policy Observatory summarise the issues that may arise as a result, and state that as a result of the ability of UK Ministers to make future changes using Statutory Instruments under the EU Withdrawal Act 2018:

Within the UK, there is tension between the regulatory divergence that these Statutory Instruments (SIs) permit and the imperative to maintain open borders within the UK. Prime Minister Johnson indicated that he is keen for the UK standards to diverge from those of the EU,[1] but Scotland wishes to maintain alignment with EU regulation.[2] Under the new Withdrawal Agreement, if passed, Northern Ireland would continue to be bound by EU law in the areas we review and the SIs would have to be amended.[3] But divergence could undermine both the UK’s ability to undertake a unified approach to external trade agreements and also the maintenance of the UK’s internal free movement of goods. With respect to external trade agreements, such as with the United States, extensive scope for ministers to change food safety legislation would provide a relatively clear path for a UK Prime Minister to overcome parliamentary opposition to any new trade agreements that cover agricultural and food products.

Lydgate, E., Anthony, C., & Millstone, E. (2019, November). Brexit food safety legislation and potential implications for UK trade: The devil in the details. Retrieved from https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/publications/brexit-food-safety-legislation-and-potential-implications-for-uk-trade-the-devil-in-the-details/ [accessed 19 December 2019]

In the absence of a Free Trade Agreement with the EU, there will be varying impacts on different agricultural sectors. An analysis commissioned by the Scottish Government into sheep and lamb processing applied the EU tariff on sheep meat products for WTO Most Favoured Nation states to 2018 sheep meat export figures and found that under a no-deal scenario:

"Overall the effective tariffs on sheep meat would have been 48% of export value, ranging from 0% on offal to 68% for boneless cuts of mutton (note that tariffs are generally higher on more processed products)

"On £356m of exports the tariff bill would have amounted to £171m.

"Overall if UK exports were to face tariffs and product was to be landed in the EU at the "same delivered price as 2018 there would have needed to be a 51% price reduction in the UK for these export products (ranging from -67% for boneless mutton, -52% for fresh lamb carcases / half carcases, to -28% for frozen mutton carcases/half carcases)."19

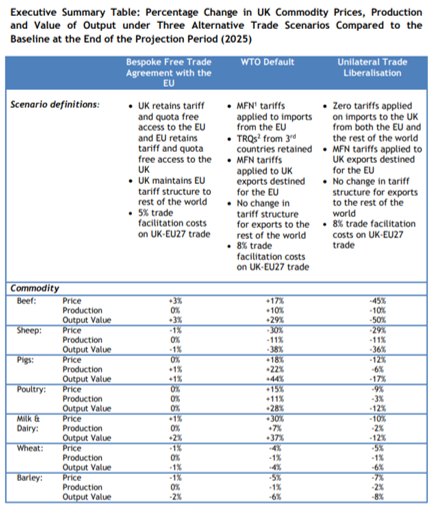

Similarly, under the Food and Agriculture Policy Research Institute UK (FAPRI) Project, funded by the four UK agriculture departments, an analysis was commissioned in August 2017 on the "Impacts of Alternative Post-Brexit Trade Agreements on UK Agriculture". Using three different trade scenarios, the researchers modelled the impact on commodity prices, production and value of output for different agricultural sectors. As a modelling exercise, the researchers necessarily made a variety of assumptions, including that exchange rates, regulatory frameworks and labour supply would remain the same. Given these and other assumptions (a full description can be found in the full report), the analysis showed significant changes in commodity prices, production and value of output for agriculture depending on the trade scenario. The figure below sets out the scenario definitions and conclusions of the sector-based modelling exercise.

The scenario with the least impact on any sector in this analysis is a bespoke free trade agreement with the EU, under which the UK retains tariff and quota free access to the EU and vice versa, and the UK maintains EU tariff structure to the rest of the world, with a 5% trade facilitation cost with EU-27 countries. The other two scenarios have large variability in the impact on each sector. Generally speaking, while an increase in price benefits producers and may cause a knock-on increase in production and output, it has the simultaneous effect of increasing food prices for consumers.20 Likewise, a decrease in price may benefit consumers but have a "depressing impact"20 on production. Both of the latter scenarios forecast large impacts in the beef and sheep sectors, which as mentioned make up a large share of Scottish agriculture.

As such, in the agricultural sector, there may be significant trade-offs associated with any approach to the future relationship with the EU. There may be significant tensions between the desired outcomes from Brexit, such as regulatory freedom, tariff-free access to markets, free movement of goods within the UK, and maintenance of environmental protection and animal welfare and food safety standards.

Fisheries

Fisheries has been a political hot potato during the Brexit process. This is unlikely to change in 2020 when the UK and the EU will wrangle over negotiating its future relationship.

The UK will become an independent coastal state on exit day, but the status-quo will be maintained during the transition period under the EU Common Fisheries Policy. After the transition period, the UK will have control over access to its waters and will set the conditions granting access to foreign vessels.