EU Structural Funds in Scotland

EU structural funds support jobs, competitiveness, economic growth, employability and sustainable development. This briefing describes structural funding in Scotland, outlines the different roles of government and public bodies in making funding decisions, and describes Brexit's impact on the current programmes. The briefing also provides a snapshot of views expressed in recent parliamentary inquiries on post-Brexit funding.

Executive Summary

Structural funds are core to the EU's Cohesion policy, which aims to reduce economic inequalities between regions in the EU.

In Scotland, the structural funds are currently worth up to €872 million across the seven-year EU budget period 2014-2020.

The EU, UK, Scottish Government, local authorities, businesses, the third sector and other local actors all have roles in managing structural funding and and delivering projects.

Despite the uncertainty created by Brexit, the current 2014-2020 programme of structural funding is likely to continue in some form.

If the Withdrawal Agreement is finalised before the UK's exit from the EU, the current funding programme will continue unchanged as a result of the transition period provisions.

If the UK exits the EU with no withdrawal agreement, i.e. a no deal scenario, the UK Treasury has issued a guarantee to underwrite the current funding programme.

After 2020, UK Government policy is to replace structural funds with a domestic fund - the UK Shared Prosperity Fund. The design, detail and value of this fund has not yet been finalised.

What are structural funds?

One of the core policies of the EU is to reduce economic inequalities between its regions. This is known as Cohesion policy or Regional policy. There are currently three main funds to deliver this policy:

The Cohesion Fund which aims to reduce economic and social disparities and to promote sustainable development in the poorer regions of Europe (meaning the UK is not eligible).

The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) which aims to strengthen economic and social cohesion in the EU by correcting imbalances between its regions. All EU regions are eligible.

The European Social Fund (ESF) which invests in people, with a focus on improving employment and education opportunities across the EU and people at risk of poverty. All EU regions are eligible.

Together, the ERDF and ESF are known as the structural funds.

Structural funds in Scotland are currently worth up to €872 million across the seven-year EU budget period 2014-2020. This figure has been lowered due to expenditure targets not being met in 2017 and 2018. To make full use of the current funds, they must be legally committed to projects in Scotland by the end of 2020 to be claimable from the EU (under the Withdrawal Agreement) or UK Government (in a no-deal scenario).

While not formally structural funds, this briefing also covers LEADER funding for rural development and European Territorial Cooperation (ETC) funding for cooperation across borders. These EU funds share come characteristics with the structural funds.

Brexit's impact on structural funding

At the time of writing, how and when the UK will leave the EU remains unknown. Despite this uncertainty, the current 2014-2020 programme of structural funding is likely to continue in some form.

If the Withdrawal Agreement is finalised before the UK's exit from the EU, the current structural funding programme (2014-2020) will continue unchanged. This is as a result of the Withdrawal Agreement's transition period provisions.1

If the UK exits the EU with no withdrawal agreement, i.e. a no deal scenario, the UK Treasury has issued a guarantee to:

underwrite the UK's allocation for structural and investment fund projects under this EU budget period to 2020.

Thom, I., & Kenyon, W. (2018, September 28). SB 18-61: European Union funding in Scotland. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2018/9/28/European-Union-funding-in-Scotland#

The UK Government's no deal notices for the ERDF and ESF say that this guarantee will allow the Scottish Government to continue to sign new projects after Brexit until the end of 2020. The notices also state that existing arrangements for the structural funds will be maintained with some flexibility for simplification. This suggests that, depending on individual grant agreements, that projects will be able to continue to spend and claim money up till programme closure (around 2023 under the so called n+3 rules).

A possible short-term supplementary option in a no deal scenario, is if the UK agrees to participate in the 2019 EU Budget (by virtue of the EU's no deal contingency measures). This would mean the UK continuing to make contributions to the EU budget, and the EU continuing to making payments to projects signed before exit, across 2019.3

UK Shared Prosperity Fund

After 2020, UK Government policy is to replace structural funds with a domestic fund:

The UK Shared Prosperity Fund – which will fill the space left by EU structural funds post-Brexit – should provide an opportunity for both governments to collaborate on transformational projects across Scotland, from the Borders to the Highlands and Islands.

David Mundell MP, UK Government. (2019, February 21). Speech by Secretary of State for Scotland, David Mundell MP: Devolution after Brexit. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/speech-devolution-after-brexit

The UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) first appeared in the Conservative Party manifesto for the 2017 General Election and in the UK Industrial Strategy.2 The UK Government issued an "update" with some details in July 2018:

"The objective of the UKSPF. The UKSPF will tackle inequalities between communities by raising productivity, especially in those parts of our country whose economies are furthest behind. The UKSPF will achieve this objective by strengthening the foundations of productivity as set out in our modern industrial strategy to support people to benefit from economic prosperity.

A simplified, integrated fund . EU structural funds have been difficult to access, and EU regulations have stopped places co-ordinating investments across the foundations of productivity. Simplified administration for the fund will ensure that investments are targeted effectively to align with the challenges faced by places across the country and supported by strong evidence about what works at the local level.

UKSPF in the devolved nations. The UKSPF will operate across the UK. The Government will of course respect the devolution settlements in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and will engage the devolved administrations to ensure the fund works for places across the UK."3

A public consultation was expected to take place before the end of 2018. In advance of this, the Scottish Parliament's Economy, Energy and Fair Work (EEFW) Committee took evidence from stakeholders and wrote to the UK Government in October 2018 with recommendations on the design of any replacement funding in Scotland.4

The UK Government held seminars with practitioners in Scotland in November 2018. However, at the time of writing, no public consultation has yet been published.

In January 2019, the UK Government said that "final decisions on UK Shared Prosperity Fund will be made during Spending Review".5 This implies that details may not be available until the Spending Review report, which would normally be published alongside the UK budget in the autumn.6

Why do we have EU structural funding?

Structural funding exists because of EU-wide efforts to reduce economic inequalities between regions - known as the EU's Cohesion policy.

Cohesion policy

The 1957 Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community (EEC) which brought together 6 countries (Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) in efforts to create a common market. The treaty stated that the signatories were:

Anxious to strengthen the unity of their economies and to ensure their harmonious development by reducing the differences existing between the various regions and the backwardness of the less favoured regions.

European Economic Community. (1957, March 25). Treaty of Rome. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Axy0023

To address these regional imbalances, various policies and funds were created. During the period from 1957 to 1988, the European Social Fund (ESF, since 1958), the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF, since 1962), and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF, since 1975) co-financed projects which had been selected beforehand by Member States, normally with little European or subnational influence.i2

In a process described as "projects to programmes", the importance of addressing regional imbalances grew; as did the funds' budgets and the role of the European Commission in directing funds. Writing for the European Commission, Vladimír Špidla states that:

In 1986 key events brought with them the impetus for a more genuine ‘European’ Cohesion Policy, most notably the Single European Act, the accession of Greece, Spain and Portugal and the adoption of the single market programme.

European Commission, Regional Policy DG. (2008, June). EU Cohesion Policy 1988-2008: Investing in Europe’s future. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/panorama/pdf/mag26/mag26_en.pdf

By 1988, reforms had made regional policy a Community competence and social and economic cohesion a Community goal. Funding was increased and the first regulations integrating the Structural Funds was adopted. These regulations introduced key principles including:

focussing on the poorest and least-developed regions

multi-annual programming

strategic orientation of investments

additionality

partnership, including at a sub-Member State level

Marco Brunazzo in Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU writes that 1988 was the "birth of Cohesion policy" and it included "a greater involvement of sub-national institutions in Community policy making".4

By 1993, the Maastricht Treaty was signed creating the European Union and laying the foundations for the single currency.5 Economic and social cohesion policy evolved with the creation of the Cohesion Fund and increased financing - now equal to a third of the EU budget across the 1993-1999 period. The treaty also created a new institution, the Committee of the Regions, and introduced the subsidiarity principle - whereby the EU will only act if this is more effective at the EU rather than national level.

Ten new Member States joined the EU in 2004 in its biggest ever enlargement. This enlargement created larger differences in income and employment across the EU. Cohesion policy reform during this time was focused on simplification and preparation for enlargement - the number of fund objectives was reduced and rules on the timely use of funds introduced.

By 2007, Cohesion policy and structural funding had changed significantly. Economic and social disparities as a result of the accession of new Member States and the EU's Lisbon Strategy (agreed in 2000) reframed Cohesion policy with a focus on growth, employment and innovation. Cohesion policy was allocated almost 36% of the EU budget and became defined by three objectives:

> Convergence: aims at speeding up the convergence of the least-developed Member States and regions defined by GDP per capital of less than 75% of the EU average

> Regional Competitiveness and Employment: covers all other EU regions with the aim of strengthening regions' competitiveness and attractiveness as well as employment

> European Territorial Cooperation: based on the Interreg initiative, support is available for cross-border, transnational and interregional cooperation as well as for networks2

Three new policy instruments were also created - JASPERS, JEREMIE and JESSICA - aimed at helping Member States access funding from the European Investment Bank and other financial institutions.

By 2014, the financial crisis was on-going and the EU had adopted (in 2010) a revised strategy - Europe 2020 - focussed on smart, inclusive and sustainable growth. Describing this strategy, the European Commission said:

Even more than its predecessor, the Lisbon Strategy, Europe 2020 emphasises the need for innovation, employment and social inclusion and a strong response to environmental challenges and climate change in order to meet this objective.

European Commission. (2010, November 29). Fifth Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion - Investing in Europe’s future. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/reports/2010/fifth-report-on-economic-social-and-territorial-cohesion-investing-in-europe-s-future

Structural funding for the 2014-2020 was tied to this strategy and included 11 thematic objectives. These are discussed further in How the current programme works (2014-2020).

From the perspective of 2018, the European Commission's Panorama Magazine summarised the changes over the last 30 years of Cohesion policy:

Cohesion Policy has evolved from a policy aimed at compensating regions for their handicaps to a policy designed to improve growth, competitiveness and foster job creation.

European Commission. (2018, March 20). Panorama 64: Cohesion Policy: 30 years investing in the future of European Regions. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/panorama/pdf/mag64/mag64_en.pdf

Structural funds in Scotland since 1989

The management and governance of structural funding in Scotland has evolved over time. Professor John Bachtler of the European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde reports that:

The first round of programmes for the 1989-93 period were largely drawn up in [the Scotland Office] with (at least some) participation of regional and local ‘partnerships’... During the 1990s, Scotland used an innovative partnership-based model for delivering Structural Funds... based on programme management executives (PMEs) that were steered by local authorities, colleges and other sectors, although the Scottish Office was responsible for claims and payments.

Bachtler, J. (2018). Brexit and Regional Development in the UK: what future for regional policy after Structural Funds?. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/20180511-John_Bachtler-Brexit_and_regional_development.pdf

There were 5 programme management executives in the 1994-1999 and 2000-2006 programmes. This was reduced to 2 in the 2007-2013 programme. In the current programme, the Scottish Government plays a central role alongside around 40 lead partners - such as local authorities and government agencies.

| Structural fund programme | Management and governance structure |

|---|---|

| 1989-93 | Scottish Office |

| 1994-99 | 5 programme management executives; Scottish Office |

| 2000-06 | 5 programme management executives; Scottish Government |

| 2007-13 | 2 programme management executives; Scottish Government |

| 2014-20 | Scottish Government |

How the current programme works (2014-2020)

This section describes how the current programme operates and how decisions on structural funding are made. Figure 1 provides an overview.

1. Role of the EU

The EU sets the structural funds' high-level objectives, the framework of rules and the formula allocating funding to regions.

Setting a framework and strategy

The European Union sets an EU-wide strategy and framework for "harmonious development" which includes the structural funds. There are numerous elements:

Europe 2020 - a ten-year strategy for "smart, sustainable and inclusive growth" including EU-wide targets for 2020.

Cohesion policy - aims to strengthen economic and social cohesion by reducing disparities in the level of development between regions. Cohesion policy is now explicitly linked to the Europe 2020 strategy.

Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2014-2020 - is a budgetary framework spanning seven years. It defines maximum annual amounts (ceilings) which the EU may spend across different categories of expenditure (headings). One of these headings is Economic, social and territorial cohesion which funds Cohesion policy.1

European Structural and Investment (ESI) Funds - this is a family of five funds pre-allocated to Member States and governed by an overarching set of rules. The scope of the ESI funds is broader than just Cohesion policy - it includes rural development and fisheries funds. The Structural Funds which contribute to EU Cohesion policy in Scotland are a sub-set of these ESI funds - see Figure 2.

Regulations - the EU sets the rules that govern the ESI funds. The overarching set of rules is called the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR). There are also more detailed fund-specific regulations and acts.

Common Strategic Framework - this is a set of principles defined by the CPR on coordinating funds and creating synergies with other EU policies and instruments.

Setting high-level objectives

The EU agreed 11 thematic objectives in 2013 to which the family of ESI funds must contribute. These thematic objectives are defined in the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR). The structural funds concentrate on a sub-set:

the ERDF supports all 11 objectives, but 1-4 are the main priorities

the main priorities for the ESF are 8-11, though 1-4 are also supported1

| Europe 2020 strategy2 | The ESI fund's Thematic Objectives3 |

|---|---|

Smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, including a set of targets for 2020.

| 1.Strengthening research, technological development and innovation |

| 2. Enhancing access to, and use and quality of, information and communication technologies | |

| 3. Enhancing the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises | |

| 4. Supporting the shift towards a low carbon economy in all sectors | |

| 5. Promoting climate change adaptation, risk prevention and management | |

| 6. Preserving and protecting the environment and promoting resource efficiency | |

| 7. Promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks in key network infrastructures | |

| 8. Promoting sustainable and quality employment and supporting labour mobility | |

| 9. Promoting social inclusion and, combating poverty and any discrimination | |

| 10. Investing in education, training and vocational training for skills and lifelong learning | |

| 11. Enhancing institutional capacity of public authorities and stakeholders and an efficient public administration | |

| Technical assistance |

Below the level of Thematic Objectives, the fund-specific regulations set more detailed investment priorities. There are:

19 investment priorities available for the European Social Fund (ESF) under four of the Thematic Objectives4

38 investment priorities available for the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) under nine of the Thematic Objectives5

The investment priorities selected by the Scottish Government are set out Table 3.

Funding distribution (to regions via Member States)

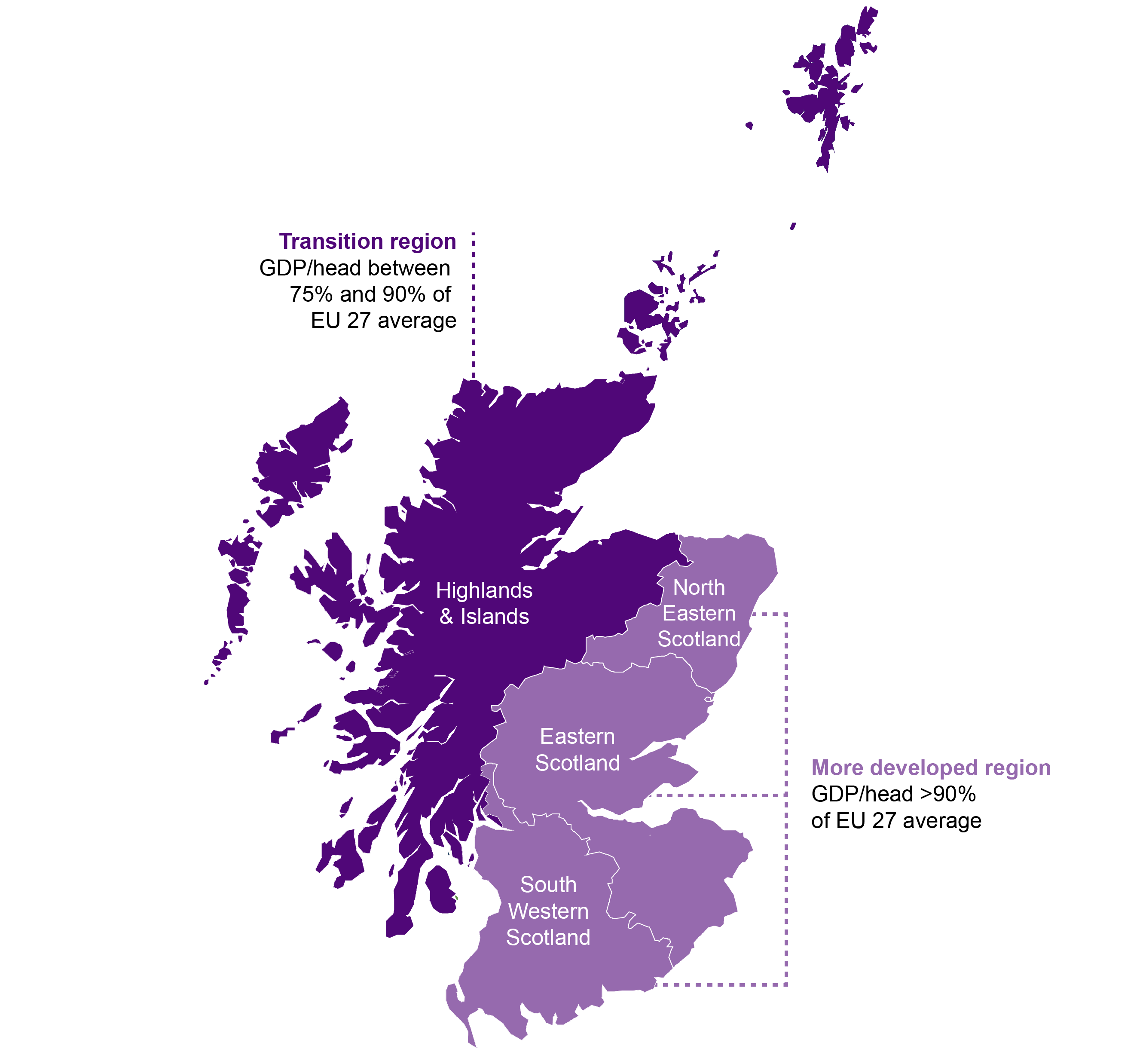

Structural funds are distributed to Member States according to a EU-wide formula linked to the economic performance of regions within Member States. The EU defines its regions according to a system knows as NUTS.i At the start of the 2014-2020 programme, there were four NUTS 2 regions in Scotland (see Map 1).ii

The distribution formula defines three types of regions:

Less-developed regions, with GDP per capita of less than 75% of the EU27 average

Transition regions, with GDP per capita of between 75 and 90% of the EU27 average

More developed regions, with GDP per capita of more than 90% of the EU27 average

The more developed region in Scotland is commonly known since 2007 as Lowlands and Uplands of Scotland (LUPS) or since 2014 as Rest of Scotland (RoS). The Highlands & Islands (H&I) is a transition region in the current programme.

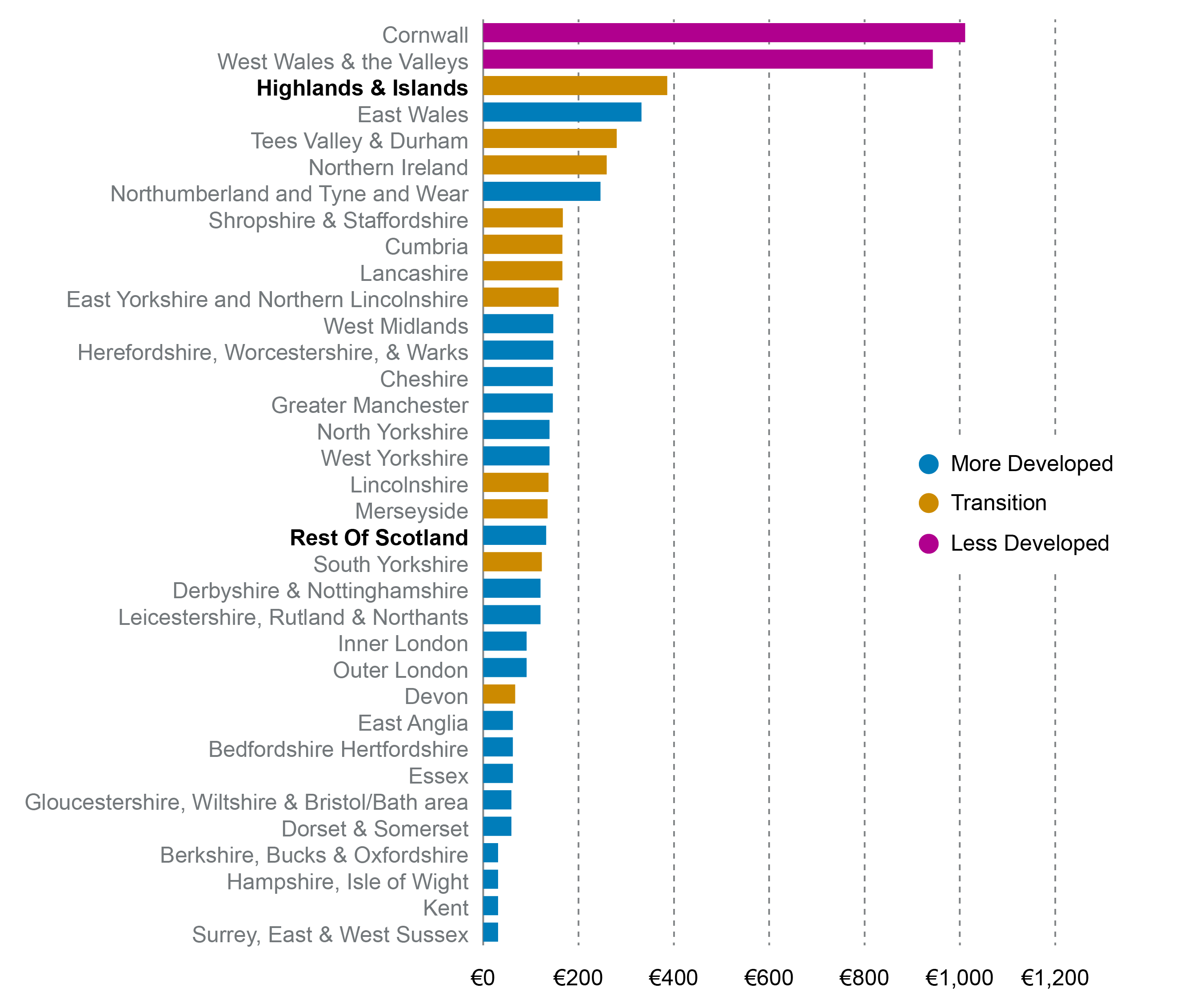

Each type of region is allocated funding using a formula set out in the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) Annex VII.1 How this formula works is relatively complicated (see Box 1). In general, the formula favours NUTS 2 regions with less GDP per person. As a result, funding is not evenly distributed across the UK, but Member States are allowed to shift funds between regions under certain circumstances (see Role of the UK - Funding distribution).

Box 1: The rules for allocating structural funds to regions

The text below is an extract from The budget of the European Union: a guide by the Institute for Fiscal Studies:

For less developed regions, the amount received is the difference between their GDP and the EU average multiplied by a percentage which depends on the per-capita GNI of the member state it is in. Regions with an unemployment rate that is higher than the EU average receive an additional payment on top of this. For example, West Wales and the Valleys has been allocated €2,005 million over the current MFF period, and Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly have been allocated €590 million. In both cases, this amounts to around €150 per person per year over the period in question. These are far higher amounts than neighbouring regions that are not poor enough to qualify for this funding: East Wales has only been allocated around €50 per person per year and Devon, Somerset and Dorset have been allocated less than €10 per person per year over the same period.

Funds for more developed regions are allocated on the basis of the characteristics of NUTS2 regions, but member states are allowed to shift funds between regions. Each region is allocated funds based on a combination of their share of:

population,

number of unemployed people in regions with an unemployment rate above the EU average,

the shortfall to the EU’s target employment rate of 75% of people aged 20 to 64,

the shortfall to the EU’s target of 40% for the number of people aged 30 to 34 who have completed tertiary education,

the overshoot of the EU’s target of less than 10% of those aged 18 to 24 who left education early,

the gap between their GDP and that of the most prosperous region in the EU, and

population living in NUTS3 regions with low population density.

Overall, funding for more developed regions is set at €19.80 per person per year (though the actual allocation between regions will depend on the characteristics listed above).

Transition regions receive a level of funding in between the two: the minimum they can receive is the same as the average of more developed regions in that member state, and the maximum is 40% of what a region would receive if its GDP per capita were exactly 75% of the EU average. There is therefore a big discontinuity in funding for regions whose GDP per capita increases over the 75% threshold, although there are transitional arrangements that ensure that regions receive at least 60% of the amount they received during the previous MFF period, and member states at least 55% of the amount they previously received.2

The initial sums allocated to each Member State were set out in a Commission Implementing Decision of 3 April 20143 but these amounts have changed over time. It is also important to remember that Structural Funds must be match funded (co-financed), normally by the public sector, so the total figure spent on structural fund priorities is greater than the amount of money coming from the EU.

Up to date information on both EU and national funding plans can be found on the European Commission's cohesion policy data portal.

2. Role of the UK Government

At the beginning of the programme period (2014-2020) the UK Government and European Commission were required to agree a Partnership Agreement setting out how the suite of European Structural & Investment (ESI) funds will be spent and the types of activity that can be funded.

The Partnership Agreement:

translates the thematic objectives and guidelines set out by the European Commission in the Common Strategic Framework into the national and regional context... The document is meant to be prepared in cooperation with partners in accordance with a multi-level approach to governance, and in dialogue with the Commission.

European Parliamentary Research Service. (2015, August 5). How The EU Budget Is Spent: The European Structural And Investment Funds. Retrieved from https://epthinktank.eu/2015/08/05/how-the-eu-budget-is-spent-the-european-structural-and-investment-funds/

The Partnership Agreement defines the Scottish Government as the Managing Authority for both structural funds in Scotland. As a Managing Authority, the Scottish Government authored its own chapter in the Partnership Agreement.2

Defining high-level outcomes

For each of the EU's thematic objectives, the Partnership Agreement describes: the UK's economic context; challenges and opportunities; and, UK-wide objectives and investment priorities. Cross-cutting issues required by the EU (for example equalities and sustainable development) are also addressed.1

In the Scotland chapter, the Scottish Government describes the "niche" where it sees the European Structural & Investment (ESI) funds fit, and sets out the types of activities it intends to use the funds for.1

Funding distribution within the UK

Regions within the UK are eligible for structural funding based on an EU-wide formula, but Member States are allowed to shift funds between regions under certain circumstances.

In the 2014-2020 programme, the UK has made use of this flexibility. The Partnership Agreement states:

The UK Government believes that the allocations to the categories of regions and the EU formula for the individual regions used to determine the allocations to the categories of regions, does not result in a fair distribution of funding across the UK, with each of the Devolved Administrations (DA) set to lose significant funding vital for economic growth. The UK’s overall allocation is set to fall by 5 per cent; however, if the EU formula were applied across the UK then this would see DA allocations fall by 27 per cent on average while the allocation to England would rise by around 7 per cent.

... In view of this, the UK Government has proposed to re-allocate EU Structural Funds to minimise the impact of sudden and significant cutbacks in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. This means that each Administration is only subject to an equal percentage cut of around 5 per cent in funding compared to 2007-13 levels.

UK Government. (2014, October 30). European Structural and Investment Funds: UK partnership agreement, 2014 to 2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/european-structural-and-investment-funds-uk-partnership-agreement [accessed 7 September 2018]

The relatively large drop in funding for the devolved administrations was due to some regions in England tipping over into the category of regions eligible for greater funding, under the new rules. To re-balance the situation the UK Government sought to deviate from the EU framework and reallocate money that would have gone to England to the devolved administrations. The UK Government announcement in March 2013 describes Scotland receiving:

an uplift of €228 million compared to the amount that Scotland would receive under the EU formula

UK Government. (2013, March 26). Allocation of EU structural funding across the UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/allocation-of-eu-structural-funding-across-the-uk [accessed 7 September 2018]

The UK also sought to compensate for a relatively large drop in funding for the UK's two less developed regions (Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly and West Wales and the Valleys) by applying to the European Commission for permission to transfer 3% of the funding allocated to other regions. 3% is the maximum transfer allowed under the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR). The request was granted.

This increased allocation to Wales and Scotland was contested in the courts by a number of local authorities in England. The court decision upheld the allocation decision but required an equality impact assessment to be carried out.3

This equality impact assessment of the allocations demonstrated significant regional differences in funding per capita across the UK (see Figure 3).

3. Role of the Scottish Government

The Scottish Government holds various roles in relation to the structural funds:

Managing Authority - responsible for the efficient management and implementation of the operational programme

Certifying Authority - responsible for submitting certified statements of expenditure and applications for payment to the European Commission

Audit Authority - responsible for audit of the management and control systems

Lead Partner – responsible for supporting the delivery of programme activities1

In its role as Managing Authority, the Scottish Government agreed operational programmes for both the ERDF and ESF with the European Commission. These operational programmes set out in detail the level of funding available for different types of activity for the whole programme period.

The EU defines what information operational programmes must contain though the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) Title II.

Identifying priorities

For the 2014-2020 programme and as part of the operational programme1 for each structural fund, the Scottish Government has:

identified the EU Cohesion policy's Thematic Objectives of relevance to Scotland

selected a limited set of the EU's available investment priorities to concentrate on

assigned the available budget to these objectives and investment priorities

This process must be done following the rules of each fund as laid down by the EU, for example on co-financing rates or concentration on a limited number of priorities. The rules for transition regions are generally more flexible compared with more developed regions.

The Scottish Government has chosen eight Thematic Objectives (out of 11 identified by the EU). Within these objectives, the Scottish Government has chosen 13 investment priorities (out of 57 identified by the EU). See Table 3 for more details.

For each investment priority "axis" the operational programmes define:

specific objectives and expected results

headline indicators and 2023 targets

actions to be supported by the fund

guiding principles for selection of operations

planned use of financial instruments or major projects (where appropriate)

a performance framework (with 2018 and 2023 targets)

a financing plan

| EU Cohesion Policy - Thematic Objectives | Investment priorities (selected by the Scottish Government from an EU defined list) |

|---|---|

| 1.Strengthening research, technological development and innovation | 1b - promoting business investment in R&I, developing links and synergies between enterprises, research and development centres and the higher education sector... |

| 2. Enhancing access to, and use and quality of, information and communication technologies | 2a - Extending broadband deployment and the roll-out of high-speed networks and supporting the adoption of emerging technologies and networks for the digital economy (Highlands & Islands only) |

| 3. Enhancing the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises, | 3d - Supporting the capacity of SMEs to grow in regional, national and international markets, and to engage in innovation processes |

| 4. Supporting the shift towards a low-carbon economy in all sectors | 4e - Promoting low-carbon strategies for all types of territories, in particular for urban 4f - Promoting research and innovation in, and adoption of, low-carbon technologies areas, including the promotion of sustainable multimodal urban mobility and mitigation-relevant adaptation measures |

| 5. Promoting climate change adaptation, risk prevention and management | None selected |

| 6. Preserving and protecting the environment and promoting resource efficiency | 6c - Conserving, protecting, promoting and developing natural and cultural heritage 6d - Protecting and restoring biodiversity and soil and promoting ecosystem services, including through Natura 2000, and green infrastructure 6g - Supporting industrial transition towards a resource efficient economy, promoting green growth, eco-innovation and environmental performance management in the public and private sectors |

| 7. Promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks in key network infrastructures | None selected |

| 8. Promoting sustainable and quality employment and supporting labour mobility | 8i - Access to employment for job seekers and inactive people, including the long term unemployed and people far from the labour market, also through local employment initiatives and support for labour mobility 8ii - Sustainable integration into the labour market of young people (YEI), in particular those not in employment, education or training, including young people at risk of social exclusion and young people from marginalised communities, including through the implementation of the Youth Guarantee (SW Scotland only) |

| 9. Promoting social inclusion and, combating poverty and any discrimination | 9i - Active inclusion, including with a view to promoting equal opportunities and active participation, and improving employability 9v - Promoting social entrepreneurship and vocational integration in social enterprises and the social and solidarity economy in order to facilitate access to employment |

| 10. Investing in education, training and vocational training for skills and lifelong learning | 10iv - Improving the labour market relevance of education and training systems, facilitating the transition from education to work, and strengthening vocational education and training systems and their quality... |

| 11. Enhancing institutional capacity of public authorities and stakeholders and an efficient public administration | None selected |

Funding distribution (to strategic interventions)

As the Managing Authority, the Scottish Government allocates funds to Lead Partners through Strategic Interventions. This stage in the funding distribution is not required by EU rules, but is how the Scottish Government has chosen to manage the structural funds.

Strategic interventions are described by the Scottish Government's operational plans:

Structural Funds programmes in Scotland for 2014-20 will be structured around Strategic Interventions – groups of projects of scale, longevity and ambition that can achieve long term change, but also ensure long-term stability of funding in support of that identified required change. Selection of operations will therefore operate on two levels, with the strategic intervention selected first, and the individual operations within it able to be added over a longer timeframe to ensure that the whole group of projects performs and delivers the expected results.

Scottish Government. (2016, November 4). European Structural and Investment Funds: operational programmes 2014-2020. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.scot/publications/esif-operational-programmes-2014-2020/ [accessed 7 September 2018]

Originally, the Scottish Government envisaged only a small number of Strategic Interventions. However this number has grown because of compliance requirements.

There are currently 14 strategic interventions, which align with EU and Scottish Government priorities. Figure 4 outlines the strategic interventions, the value of their operations and how they align with the EU's cohesion policy objectives.

More detail on each strategic intervention is available in Current projects and activity.

4. Role of Lead Partners

The role of Lead Partners is to manage and deliver the strategic interventions.

Managing strategic interventions

Lead Partners are often the organisations taking the lead on behalf of a group of partners. They are typically organisations with the capacity and capability to manage the funds and provide match funding of their own.

There are currently 40 Lead Partners. The top ten by value of allocated budget are shown in Figure 5. All other Lead Partners (with the exception of the Big Lottery Fund) are local authorities.

The Lead Partners' main task is to convert the ESF & ERDF budgets allocated to them into appropriate projects - called operations - and then oversee delivery.2

Operations are the point when funding for individual projects becomes legally committed and money can be drawn down from the EU.

Lead Partners will usually spend and claim a significant proportion of the structural funds directly, but may also procure services or distribute funding to others though a challenge fund.3

Box 2: challenge funds

Challenge funding is one of the available delivery methods. This is an open and competitive application process where organisations bid for structural funding to deliver projects. Depending on the type of challenge fund, the bidding organisations may have to provide match-funding. In other cases, the Challenge Fund will have been match-funded by the Lead Partner already, so further match-funding is not necessary.3

How much funding has gone to projects?

To access the full amount available to Scotland, the current round of structural funding needs to be committed to projects by the end of 2020. Funds committed by that time can be spent up to 2023. This is the case under the UK Treasury guarantee or the proposed Withdrawal Agreement.

As of 28 February 2019, 67% of the available funds had been committed to projects. See Table 4 for a breakdown.

Only funds committed by the end of 2020 can be claimed, which leaves a period of 20 months from the time of writing to commit the remaining funds to projects. Projects must meet the programmes' rules and performance requirements. In addition, structural funding needs to be match-funded. This means that uncommitted structural funding still needs to be matched by the Scottish public sector if it is to be drawn down.

The average rate of EU funding for operations in Scotland is 44% (42% for ERDF and 47% for ESF).

| Programme value (€) | Committed (€)1 | % of Programme Committed | Paid Claims (€)2 | % of Programme Claimed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERDF | Highlands & Islands | 104,658,615 | 84,157,813 | 80% | 6,244,504 | 6% |

| ERDF | Rest of Scotland | 347,783,180 | 264,226,397 | 76% | 36,940,606 | 11% |

| Subtotal | 452,441,795 | 348,384,210 | 77% | 43,185,110 | 10% | |

| ESF | Highlands & Islands | 76,598,544 | 32,701,853 | 43% | 5,231,869 | 7% |

| ESF | Rest of Scotland | 343,617,686 | 200,137,526 | 58% | 42,099,947 | 12% |

| Subtotal | 420,216,230 | 232,839,379 | 55% | 47,331,816 | 11% | |

| ERDF+ESF | Total | 872,658,025 | 581,223,589 | 67% | 90,516,926 | 10% |

Structural funds in Scotland are currently worth up to €872 million across the seven-year EU budget period 2014-2020. This figure has been lowered from €941 million at the start of the programme by:

€22 million at the end of 2017, and

around €50 million at the end of 2018

due to expenditure targets not being met. At the end of 2018, the ESF programme value was lowered by €26.6 million (6.0%) largely due to the Youth Employment Initiative, and the ERDF programme value was lowered by €23.1 million (4.9%).1

In the latest update to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee in December 2018, the Scottish Government states:

At the end of 2017, we were notified that the value of the programmes had reduced by €22 million as a result of expenditure targets for 2017 not being met. Officials are working hard to ensure the expenditure paid out [by] lead partners is claimed from and paid by the Scottish Government in order that it can be claimed from the [European Commission]. Expenditure targets for 2018 include those for the Youth Employment Initiative, which will again not be met largely due to the reduced numbers of young people who have been supported though this Initiative. This reflects the drop in the numbers of unemployed people in the South-west of Scotland to closer to the national average.

Scottish Government. (2018, December 14). Letter to CTEEA Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_European/Meeting%20Papers/20190117CTEEAPublicPapers.pdf

5. Role of Delivery agents & organisations

Delivery agents deliver projects and activities and are funded by the structural funds.

Project delivery

Delivery Agents are often the same organisations as Lead Partners, but at this point funding has been legally committed to specific operations.

Delivery Agents must be eligible organisations i.e. public bodies, third sector or not for profit organisations. However the final beneficiaries of operations will be, for example: businesses, third sector groups or individuals seeking to improve their skills.

COSLA states that Scottish local authorities deliver around one third of funding through Business Gateway, Community Planning Partnerships and Business Loans Scotland.1 But the Scottish Government is by far the largest single Delivery Agent.

Current projects and activity

There are over 200 operations funded through the current structural funding programme, organised through 14 strategic interventions. Table 5 describes the aim of each strategic intervention and provides a brief flavour of current activity.

| Strategic Intervention (SI) | What it aims to do | Current operations |

|---|---|---|

| Employability (ESF) | Promote jobs, routes to employment and increased skills for unemployed people. | Local Authority-led employability pipelines to help people into employment, and a national fund for third sector organisations (operated by Skills Development Scotland). |

| SME holding fund (ERDF) | Provide microfinance, debt and equity support to SME for competitiveness, growth and R&D. | Lending and investment to SMEs with growth and/or export potential through five Scottish Growth Scheme funds. |

| Youth Employment Initiative (ESF) | Reduce unemployed and socially excluded young people (South West Scotland only). | The YEI is now closed. |

| Business competitiveness (ERDF) | Assist SMEs to be competitive, innovative and grow. | Support for SME growth, including operations supporting renewables innovation in Orkney and Cromarty Forth port infrastructure. |

| Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction (ESF) | Support equal opportunities, skills, social enterprises and long-term solutions for reducing poverty. | Area-specific money advice, social inclusion and employment support, including a Challenge Fund for community groups. |

| Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme (ERDF) | Support a low-carbon economy though research and investment in technology. | Funding for low carbon energy and electric vehicle projects awarded in 2018. |

| Resource Efficient Circular Economy (ERDF) | Support business and public sectors to increase resource efficiency. | Zero Waste Scotland's Circular Economy Accelerator Programme aimed at SMEs. |

| Developing Scotland's Workforce (ESF) | Improve work skills and expand apprenticeships. | Funding to colleges and universities for progression and upskilling in specific sectors, including food & drink, life sciences and renewable energy. |

| Low Carbon Travel and Transport Programme (ERDF) | Invest in active travel, smart ticketing and electric vehicle charging hubs. | Challenge Funds for smart ticketing on buses or electric car charging and walking and cycling infrastructure. |

| Scotland’s 8th city – the smart city (ERDF) | Use new technologies to improve city services and address urban challenges. | Funding for street lighting, mobile working, hydrogen fuel cell buses and other city-based projects. |

| Digital infrastructure (ERDF) | Improve broadband and mobile connectivity. | Funding for the mobile masts to extend 4G coverage in the Highland & Islands. |

| Green infrastructure (ERDF) | Improve access to urban green spaces. | Challenge Funds for urban greenspace projects now closed. |

| Business innovation (ERDF) | Promote investment in research and innovation. | Business support, for example the Northern Innovation Hub for life sciences, tourism, food and drink and creative industries. |

| Technical Assistance | Strengthen administrative capacity to manage the ERDF and ESF programmes. | Management costs across various public bodies. |

| Natural and Cultural Heritage Fund (ERDF) | Promote and sustainably develop natural and cultural heritage assets. | New fund for projects in the Highaland & Islands. |

ETC funding

In addition to the structural funds, a set of EU funding is available for territorial cooperation across borders. This European Territorial Cooperation (ETC) programme is commonly known as INTERREG.

ETC funding is grouped into various cross-border funding areas. Organsations generally bid for funding in partnership with others from different countries in the programme area.

The most valuable ETC programmes to organisations in Scotland are North West Europe and Interreg VA, and the Highlands & Islands region has benefited from 47% of all ETC funding secured during the current period.

| Funding programme | Total value to Scotland (€) |

|---|---|

| North West Europe | 22,857,948 |

| Interreg VA Cross Border | 22,846,971 |

| North Sea Region | 8,355,988 |

| Northern Periphery & Arctic | 6,811,420 |

| Atlantic Area | 5,243,301 |

| Interreg Europe | 1,618,458 |

| 2SEAS* | 490,554 |

| URBACT III | 38,234 |

| Baltic Sea Region* | 30,000 |

| Total | 68,292,874 |

After 2020, the European Commission proposes a new generation of interregional and cross-border cooperation programmes. The proposed EU regulation states that non-EU Member States are able to participate. This means that regions of the UK could still participate in ETC subject to negotiations on the UK's future relationship with the EU.

LEADER funding

LEADER is an EU funding programme, but is not part of the structural funds. There are however some similarities (and common histories in Cohesion policy).

According to the Scottish Rural Network, which is responsible for promoting the LEADER programme in Scotland:

The aim of LEADER is to increase support to local rural community and business networks to build knowledge and skills, and encourage innovation and cooperation in order to tackle local development objectives.

Scottish Rural Network. (n.d.) LEADER. Retrieved from https://www.ruralnetwork.scot/funding/leader [accessed 8 March 2019]

LEADER is part of the Scottish Government's Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP). LEADER is co-financed by EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funding and the Scottish Government. It is worth around £82 million over the 2014- 2020 funding period.i2 LEADER is a rural fund, with city and large town areas ineligible for grants.

Funding model

The model for funding distribution is distinct to that chosen by the Scottish Government for structural funds.

The Scottish Government allocates funding to 21 Local Action Groups. Grants are awarded by the Local Action Groups to projects that support delivery of a Local Development Strategy.1 Under the EU rules, this approach is known as community-led local development.2

The operational plans for the ERDF and ESF both state that these programmes will not be implemented through community led local development. Instead the structural funds take a national approach though strategic interventions informed by more local actors like Community Planning Partnerships or delivered though regional partners such as Highlands & Islands Enterprise.3

Local Action Group indicative allocations and how much they have awarded in grants is set out in Table 7:

| Local Action Group (LAG) | Indicative budgets (£) | % spent or committed |

|---|---|---|

| Argyll and the Islands | £4,886,126 | 52% |

| Angus | £2,750,186 | 95% |

| Ayrshire | £5,783,731 | 68% |

| The Cairngorms | £2,968,517 | 91% |

| Dumfries and Galloway | £5,595,370 | 97% |

| Fife | £3,397,670 | 92% |

| Forth Valley & Lomond | £2,783,013 | 95% |

| Greater Renfrewshire & Inverclyde | £2,324,196 | 68% |

| Highland | £8,805,388 | 94% |

| Kelvin Valley & Falkirk | £2,824,399 | 94% |

| Lanarkshire | £4,066,953 | 85% |

| Moray | £3,453,040 | 75% |

| North Aberdeenshire | £3,290,237 | 85% |

| Outer Hebrides | £3,177,666 | 100% |

| Orkney Islands | £2,512,250 | 85% |

| Rural Perth & Kinross | £3,800,124 | 84% |

| South Aberdeenshire | £2,831,742 | 92% |

| Scottish Borders | £4,018,427 | 100% |

| Shetland | £2,467,085 | 87% |

| Tyne Esk | £3,490,769 | 94% |

| West Lothian | £2,173,112 | 65% |

| Totals | £77,400,001 | 86% |

As with structural funds, only funds committed by 2020 can be claimed back. The Scottish Government LEADER team monitor commitment and spend progress through the LEADER IT system. Examples of projects funded under the 2014-2020 LEADER fund are provided on the Local Action Group websites.

Is current structural funding effective?

After 30 years of cohesion policy, there are still significant disparities in economic performance between regions within the UK (as well as between regions within Scotland).12 That said, structural funding levels have been small relative to the UK's GDP, even at a regional level.34

In 2013, the Scottish Government wrote:

European Funds have played a pivotal role in supporting the Scottish economy... However, when considering the impact the [2007-2013] programmes have had it is important to remember that they were developed before the economic downturn... Not all projects have found it easy to deliver the outcomes they initially projected, and taken together, the projects have perhaps not achieved as big an impact on the economic situation in Scotland as we might have hoped.

Scottish Government. (2013, May 14). European Structural Funds 2014-2020 programmes consultation. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/european-structural-funds-2014-2020-programmes-consultation/pages/2/

Professor Steve Fothergill at Sheffield Hallam University states:

Unfortunately, it is hard to pin down the precise impact of all this EU funding... It is reasonable to assume that in the absence of EU funding hardly any of the [funded] projects would have proceeded on the same scale if at all.

In the current programme, performance against the funds' targets and milestones is tracked though six-monthly reporting to the Joint Programme Monitoring Committee (JPMC) and Annual Implementation Reports to the European Commission. The JPMC also maintain a risk register.

Following the EU referendum in 2016 and the uncertainty this created for the structural fund programme, the Scottish Government initiated an early review. This reported in 2017 - it found that the logic behind both programmes "remains sound" but recommended five operational changes. These changes included relaxing staff cost rules and reallocating some budgets.6

The latest performance update to the JPMC in November 2018 suggests there is a significant risk that targets will not be met and access to a €50 million Performance Fund will not be opened:

At the end of this year, the programmes will be judged against both the N+3 expenditure target as at the end of 2017 and the Performance Framework. Performance Framework is a series of physical and financial targets to be delivered by 2018 and 2023, and the Performance Reserve is over €50 million of the ESF and ERDF grant allocation which is held back and can only be accessed if sufficient progress has been made towards the 2018 Performance Framework targets.

If there is not sufficient progress, each priority, at programme area level (i.e. H&I or Rest of Scotland), could lose the Performance Reserve outlined in the Operational Programmes, with this money potentially being lost to that priority and reallocated to more successful areas if the targets are not met. Progress is continuing to be monitored and the MA is working closely with Lead Partners to maximise the expenditure and activity reported but there is a significant risk in a number of areas that these targets may not be met.

Scottish Government. (2018, November). JPMC 12-03a - ESF and ERDF programme performance against the operational programmes. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/joint-programme-monitoring-committee-minutes-november-2018/

This quote refers to a mid-point review required by the European Commission and based on the Scottish Government's annual implementation report for 2018, which will be submitted around June 2019.

What role has the Scottish Parliament played?

Scottish parliamentary committees have scrutinised structural funding in Scotland.

Ahead of the current 2014-2020 structural funding programme, in 2011-2012 the Europe and External Relations (EER) Committee held an inquiry considering "lessons learned" from the 2007-13 programmes with a view to improving Scotland's performance. This inquiry explored:

the obstacles to securing funds, and how good practice can be shared

the nature of the "red tape" that surrounds the programme

the role of the Scottish Government in guiding/supporting would-be applicants1

Following the 2012 inquiry report, the Committee started to receive six monthly updates from the Scottish Government. Late in 2013, the EER Committee took further evidence from European Commission officials and Scottish stakeholders and published a letter after the (late) conclusion of negotiations on the EU budget and regulatory package for the ESI Funds.2

The referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union was held on 23 June 2016 - two and a half years into the current seven-year programme. Brexit's impact on the structural fund programme has broadened interest in the funds:

Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs (CTEEA) Committee - has continued to receive six monthly updates from the Scottish Government throughout Session 5 and received its latest update in December 2018.3. The Committee took evidence from the Cabinet Secretary for the Economy, Jobs and Fair Work in September 2017 on both the previous and current programmes,4 and wrote a letter to the UK Government jointly with representatives from the London Assembly and National Assembly for Wales in December 2017 calling for funding levels to be maintained and decision-making devolved in any future programme.5

Economy, Energy and Fair Work (EEFW) Committee - held an inquiry into structural funding for economic development in 2018. This inquiry was timed to influence the design of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund and letters with recommendations were sent to the UK and Scottish Governments in October 2018.6

Finance and Constitution (FC) Committee - issued a call for evidence followed by a roundtable on the funding of EU competences (including structural funding) in June 2018.7 In March 2019, the FC Committee launched a specific inquiry into the funding of structural fund priorities after Brexit.

Post-Brexit questions

This section provides a snapshot of views expressed by people and organisations who have responded to recent Scottish Parliament committee inquiries or European Commission surveys.

How should funding be distributed?

Evidence submitted to the Finance and Constitution Committee's Funding EU Competences inquiry discussed how any replacement structural funding could be distributed.1

Professor Michael Keating set out options for allocating structural funds after Brexit:

the present system could be rolled over

the moneys could be included in the block grant and subject to the Barnett Formula

the moneys could be used for UK programmes or tied to UK policy frameworks

do away with structural funding altogether2

Under the draft Withdrawal Agreement / UK Treasury guarantee, the present system will largely "roll over" after Brexit until the end of the current 2014-2020 programme. The UK Government have indicated that a new UK Shared Prosperity Fund will replace structural funding after 2020, but there are few details available about how this scheme will work.

On using the Barnett Formula for allocating funding to Scotland, Nicolo Bird and David Phillips of the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) state:

The Barnett Formula is simple and well understood. The Scottish Government also has significant flexibility over how it spends annual increments to its funding as a result of the application of the Barnett formula. But the formula has design flaws which mean its use the allocation of funding to replace current EU schemes should be avoided.

Bird, N., & Phillips, D. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/Written_Evidence_on_Funding_of_EU_Competences.pdf

Professor Michael Keating states that, using Barnett Formula would mean:

the devolved nations would keep their historic relativities but any changes would be applied on a pound for pound basis per capita and each pound would represent a smaller proportion of their existing budgets. As the overwhelming probability is that these funds will be cut rather than increased, the devolved nations would face less severe reductions than under the present system. Contrary to some recent comment, Barnett does not mean that the nations would get only a population-based share of expenditure. Indeed, Barnett would be rather favourable to them.

Keating, M. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/Written_Evidence_on_Funding_of_EU_Competences.pdf

The IFS refer to the Indexed Per Capita (IPC) formula, as utilized in the Fiscal Framework, as an alternative to the Barnett Formula to deliver the same percentage change in funding per person in Scotland as in England. But IFS also point out that:

the UK and Scottish governments may want to allocate funding in ways that account for more than just relative population growth and initial levels of funding. This could include using local, regional or national level characteristics, and competitive bidding processes. There are also decisions to be taken as to whether funding schemes will be designed and operated at the UK level, devolved government level, or some other level (e.g. city-region).

Bird, N., & Phillips, D. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/Written_Evidence_on_Funding_of_EU_Competences.pdf

Professor David Bell modelled a "needs-based" allocation of funds to NUTS 3 regions in the UK, based on the current EU method of categorising regions by GDP per head. Professor Bell states:

Some [of the results] are quite surprising. For example, Dundee is the only major city [in Scotland] that would qualify in either category [of higher funding], while more areas in the south of the country would qualify compared to those in the north.

Bell, D. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/Written_Evidence_on_Funding_of_EU_Competences.pdf

Professor Bell also discusses a "competitive" allocation of funds. He cites the City Deals and Growth Deals as an example of current competitive practice.

The IFS sets out and discusses a list of helpful questions:

Should structural funding be replaced? If so, what are the objectives?

How will funding sits alongside other economic and regional policy?

What characteristics should be used for assessing ‘need’ for regional funding, and at what geographical level should such assessments take place?

How redistributive/'targeted' should the funding be?

At what level of government should decisions on allocations of funding to broad thematic areas and particular projects be taken?

Should the funding be ring-fenced for developmental purposes or should the organisations (such as Scottish Government or local authorities) to whom funding is allocated have much more discretion over its uses?

How frequently and to what extent should allocations be updated to account for changing socio-economic conditions of different areas?

Is there a role for ‘outcomes’ as well as ‘characteristics’ in determining funding allocations?

Is there a role for competitive bidding between areas for funding allocations, as well as between projects within those areas?3

What barriers do projects face?

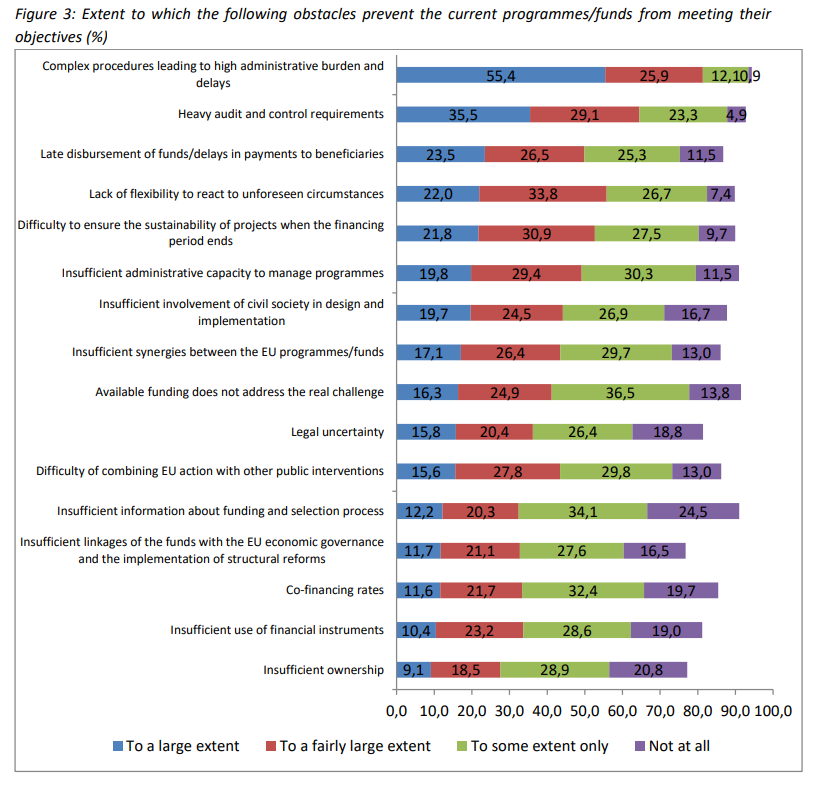

At a European Union-wide level, a consultation in 2018 identified:

complex procedures leading to high administrative burden and delays, and

heavy audit and control requirements

as the most important obstacles preventing current programmes/funds from successfully achieving their objectives.1

In Scotland, some of the barriers facing projects were highlighted in evidence to the EEFW Committee's 2018 structural funds inquiry.3

SLAED - the network of Scottish local authority economic development officers - described significant delays to the start of the current structural fund programmes:

...the structural fund regulations were only adopted on 17th December 2013 and the Scottish programmes one year later in December 2014; ... the first Grant Offer letters [were not] issued until December 2015 – most were not issued until well into 2016.

Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-009-SLAED.pdf

Dumfries and Galloway Council said:

Delivery of ERDF commenced in April 2016, some 12-18 months later than originally anticipated. This was due to late changes in expenditure methodology (scrapping of unit costs) and the associated delay caused by rewriting the funding applications. The delay has resulted in lower than anticipated expenditure and this is something that we will not be able to fully compensate for in the time remaining.

Dumfries and Galloway Council. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-005_-_Dumfries_and_Galloway_Council.pdf

COSLA said:

The start of the current programmes suffered delays, including IT issues - EUMIS for ERDF/ESF is not considered to be working well and creates a hindrance (although the system used for the EMFF funding by Marine Scotland is a good example of how an IT system can benefit the managing authority, applicant and staff team). This means that, three years into the programming period, few funds have been claimed from the EU.

COSLA. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-017-COSLA.pdf

Highlands and Islands European Partnership (HIEP) confirmed that making claims has challenges:

Claims from HIEP partners have been submitted and gone through the verification scale and, in some cases the detail of the verification has increased. There are concerns that the way the rules were applied may not be consistent across Strategic Interventions and operations. The evidence requirements were not unified and this led to more requests and high volumes of data moving back and forth between the Managing Authority and the Lead Partners – this inevitably lead to forced errors and higher risk. It seems for each layer of evidence mastered, there is a further layer hiding beneath. The partners have also expressed their concern at the sudden introduction and retrospective application of new rules, conditions and interpretations.

Highlands and Islands of Scotland European Partnership. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-004__-_Highlands_and_Islands_European_Partnership.pdf

Aberdeenshire Council said:

There is therefore a significant delay between funding being allocated, spent and finally claimed back from the European Union.

Aberdeenshire Council. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-001_-_Aberdeenshire_Council.pdf

Universities Scotland said:

A real barrier with ESIF relates to the management of projects. Institutions have not received sufficient information on future funding which prevents them from committing to longer term undertakings (e.g. recruiting new staff, providing places on courses, particularly undergraduate degrees which are a 3-4 year commitment) because there has not been confidence in receiving funding over a >2 year term.

Universities Scotland. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-015-Universities_Scotland.pdf

University of the Highlands and Islands said:

To date, our major hurdles have been in commitment and process, but accountability and reporting have also caused concern, being extremely complex, bureaucratic and inflexible. It has proved difficult to ascertain clear guidance on eligibility and engage in constructive discussions about improvements - for example, on how evidencing student participation could be simplified and aligned more closely with existing systems, rather than adding an extra layer of bureaucracy.

University of the Highlands and Islands. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-032-University_Highlands_Islands.pdf

Is the structure right?

The strategic intervention step in the process of structural funding was designed into the current Scottish programmes. According to the Scottish Government, the rationale for this model is:

Managing strategic interventions through lead partners has some very specific advantages for Scotland:

Scottish Government. (2013, December 9). European Structural Funds 2014-2020 consultation document. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/european-structural-funds-2014-2020-consultation-document/pages/3/

It gives us the tighter focus required by the [European] Commission

It gives us up-front agreement on what outcomes and impacts the programmes should achieve

It ensures funding stability (Funds and match) in the long term for important areas of work; and

It manages the audit burden at a higher level, allowing smaller organisations to focus on what they do best - delivering quality outcomes.

Some evidence to the EEFW Committee's 2018 structural fund inquiry addressed the success of this model.2

The University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) said:

The principles and aspirations behind the planning for current allocations were well intentioned. The previous 2007-13 programmes at times lacked strategic focus; error rates in eligible and compliant spend were too high, leading to funding being lost. The new approach, whereby funds would be allocated to a small, targeted number of Strategic Interventions (SIs), governed by relevant national/regional Lead Bodies, aimed to reduce such problems in 2014-20 ESIF. The SI concept had greater potential for longer-term, strategic planning and prioritisation. New delivery options, such as simplified cost models, were to be introduced, aiming to make the process more efficient and less bureaucratic.

University of the Highlands and Islands. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-032-University_Highlands_Islands.pdf

However, UHI go on to say that:

Unfortunately, in practice, many of the original aspirations have not been realised. The small number of SIs gradually expanded into a much larger number, which put a strain on the delivery mechanisms. Intended simplifications did not filter through and proved difficult to introduce with a larger number of SIs – for example, simplified cost models became difficult to develop, with uncertainty around eligibility criteria and long delays in approval.

University of the Highlands and Islands. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-032-University_Highlands_Islands.pdf

COSLA said:

Our expanded role by way of the Strategic Intervention has resulted in local authorities having taken on additional responsibilities. But, often this has lessened our ability to influence. Among those councils that are acting as Lead Partners this means that they are effectively a mini-Managing Authority – but unlike the “sub-delegation” of functions allowed for in the EU Regulations, this alternative homegrown scheme offers less scope for local discretion and more focus in delivering national as opposed to local objectives. This time round Scottish Government agencies had unprecedented access to the EU Structural Funds programmes, and worked as envisaged in the sub-delegation arrangements. However, local authorities, as a separate sphere of government, has found this to be an excessively constraining framework – given the significant amount of time, compliance and administrative functions that Lead Partners have had to comply with.

COSLA. (2018). Evidence to Scottish Parliament Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_EconomyJobsFairWork/Inquiries/ESIF-017-COSLA.pdf

A 2017 review of the programmes by the Scottish Government, triggered by the result of the EU referendum, concluded that:

despite changes since the programmes were developed, the original intervention logic for both Programmes remains sound. However... some adjustments to both the scope and allocations are required... these measures seek to reduce the risk of the Programmes not meeting expenditure targets but maintain absolute faith with the original strategies.

Scottish Government. (2017, December). Paper 06 - Review Recommendations - 14 June 2017. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/jpmc-minutes-june-2017/

How to "simplify" the programmes?

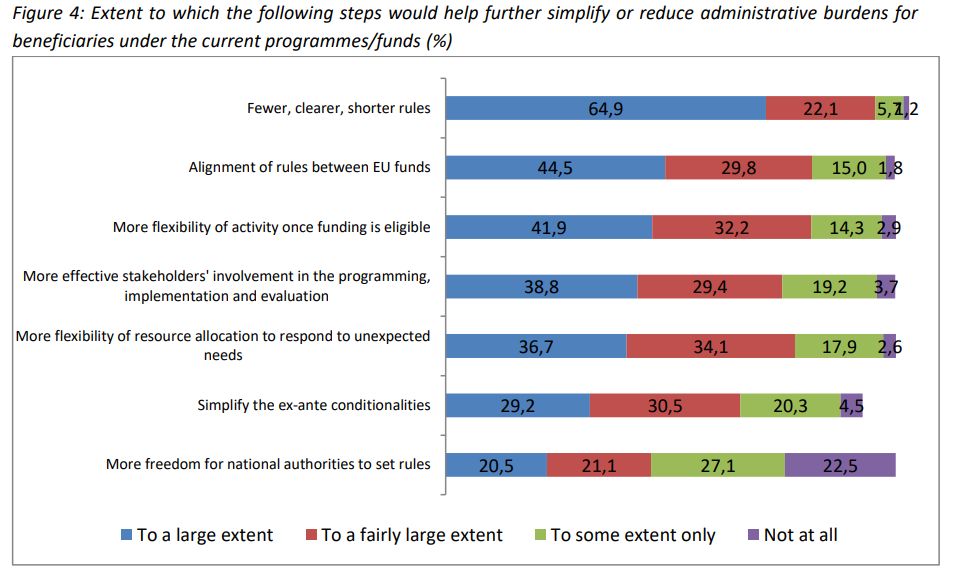

At a European Union-wide level, a consultation in 2018 identified:

fewer, clearer, shorter rules

alignment of rules between EU funds, and

more flexibility of activity once funding is eligible

as the steps most likely to help further simplify and reduce administrative burdens under current programmes/funds.1

In Scotland, some priorities areas for simplification were highlighted in evidence to the Economy, Energy and Fair Work (EEFW) Committee's 2018 structural fund inquiry.3

A large number of organisations responding to the inquiry saw opportunities to increase flexibility in project types/scope, reduce restrictions, simplify rules and cut bureaucracy.

Some of the common ideas raised were:

The need for agreed guidance from the start

More local control or regional flexibility

Alignment with existing (or emerging) structures - e.g. regional partnerships

Flexibility when targeting beneficiaries

Remove the defined thematic objectives and distinction between ERDF/ESF

Harmonise reporting across programmes or with existing systems

Relax match funding rates

Scale the audit and reporting requirements with project size or risk

Faster processing of claims

Relax rules on chargable staff costs

Sustained, long-term funding

Timely evaluations that can be used to improve delivery

Organisations also report successes with the current arrangements. For example, Zero Waste Scotland said they have had the flexibility to take different approaches to project delivery4 and the Scottish Funding Council said they had been able to successfully comply with the expenditure rules.5

It is important to note, that any changes would need to comply with EU programme rules while the UK is a member of the EU or in a transition period.

Future funding: recommendations, risks & opportunities

The key recommendations for post-Brexit structure funding from the Economy, Energy and Fair Work (EEFW) Committee's 2018 structural fund inquiry were:

to maintain the core structural approach, driven by needs and directed at people and places

to keep the best characteristics of ESIFs, including timeframes beyond electoral cycles, the focus on regional development and an ethos of partnership working

for the current allocation to Scotland under ESIFs to be the baseline for future monies and there to be no regression in funding

to ensure as seamless as possible a transition to the successor fund, and

for Scotland to decide its own internal allocation formula.1

Organisations responding to the inquiry were asked to identify opportunities and risks for any future funding.

| Opportunities | Mentioned by: |

| Continued partnership working | Local authorities, Universities Scotland, SFC |

| Medium to long term investment | Local authorities, Prof Fothergill, Colleges Scotland |

| Improving structural difficulties | Local authorities |

| Reduced administration and auditing burden | Local authorities, Industrial Communities Alliance, Colleges Scotland |

| Improved monitoring and evaluation | Local authorities, Morag Keith |

| Future evaluations more useful | Local authorities, Scottish Enterprise |

| Rethink regional economic policy | Local authorities |

| More geographically sensitive | Local authorities, Industrial Communities Alliance |

| More flexible in ability to support businesses and react to shocks | Local authorities |

| Funding based on need | Cities Alliance, Industrial Communities Alliance |

| Ability to reduce thematic restraints of current funds | Cities Alliance |

| Ability to change priorities, focus and allocations depending on environmental and societal challenges | SCVO |

| Future programmes fully aligned to Scotland’s Economic Strategy | Scottish Enterprise |

| Consider more sophisticated selection criteria beyond GDP | Highlands and Islands Enterprise |

| Future programmes should be more risk-based and innovative | Universities Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, Colleges Scotland |

| Risks | Mentioned by: |

| Funding not ring-fenced | Local authorities |

| Reduced funding | Local authorities, Industrial Communities Alliance, Morag Keith |

| Lack of consultation with stakeholders | Local authorities |

| Potential hiatus between structural funds stopping and replacement fund starting | Local authorities, Prof Fothergill |

| Short-termism | Local authorities |

| Top down management and direction of the fund | Local authorities, Industrial Communities Alliance |

| Using Barnett Formula to allocate funds | Cities Alliance, Industrial Communities Alliance, |

| New approach is too rigid | Cities Alliance |

| Ensure ongoing interventions continue (for example Graduate Apprenticeships) | Universities Scotland |

| Duplication of other schemes | Universities Scotland |