Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill

The purpose of the Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill is to make answering any questions in the 2021 Census on sexual orientation or gender identity voluntary thereby ensuring that no penalties result from non-response to these questions. This briefing provides background on the Bill, including discussion of the perceived need for, and development of, questions on sexual orientation or gender identity, including trans status/history, to be included in the Census.

Executive Summary

The Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Parliament on 2 October 2018 by the Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Tourism and External Affairs, Fiona Hyslop MSP.

The intention is that Census 2021 will take place on Sunday 21 March, and will be predominantly online.

As society changes over time, census questions have to be updated to reflect these changes. To this end, National Records of Scotland (NRS) undertake extensive consultation and research with a wide range of stakeholders on the questions as part of census planning.

The NRS conducted a "Topic Consultation" between 8 October 2015 and 15 January 2016 seeking views on the topics users felt should be included in the next census. New questions were developed based on a set of evaluation criteria, such as strength of user need. Public acceptability and data quality issues were also taken into consideration.

The Topic Consultation did not specifically address the need for a question on gender identity. However, a user need for data on sexual orientation and gender identity, especially trans status/history, was identified in the course of the research.

It is widely accepted that there are currently data gaps on sexual orientation and gender identity. Including questions on these demographics in the Census will provide valuable data for public service planning purposes and will help public bodies meet duties under the Equality Act 2010.

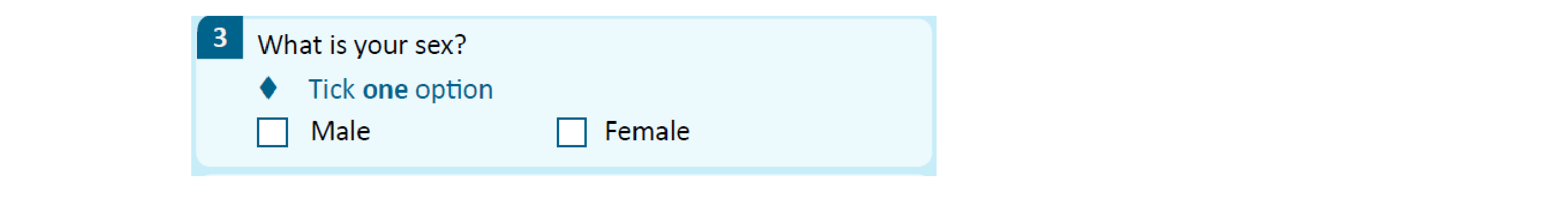

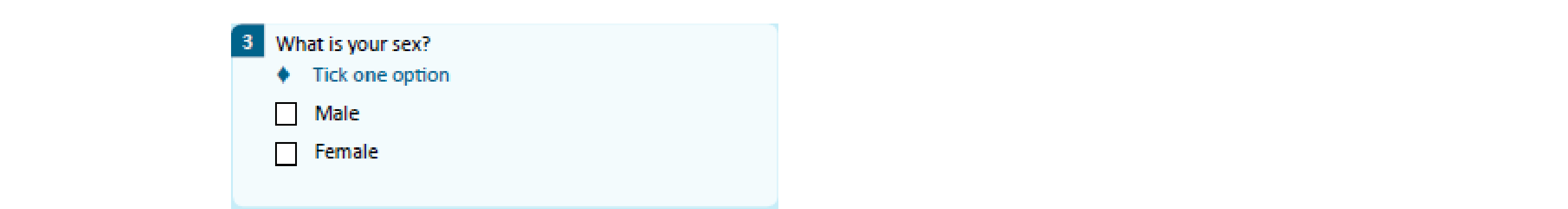

A need for a non-binary sex question was also identified. Previously the sex question has been binary - male/female.

The NRS research found that the sex and gender identity questions, and the sexual orientation questions, were publicly acceptable.

The Bill is short and aims to ensure that if, as the Scottish Government intends, questions are added to the Census on prescribed aspects of gender identity and sexual orientation, answering them will be voluntary.

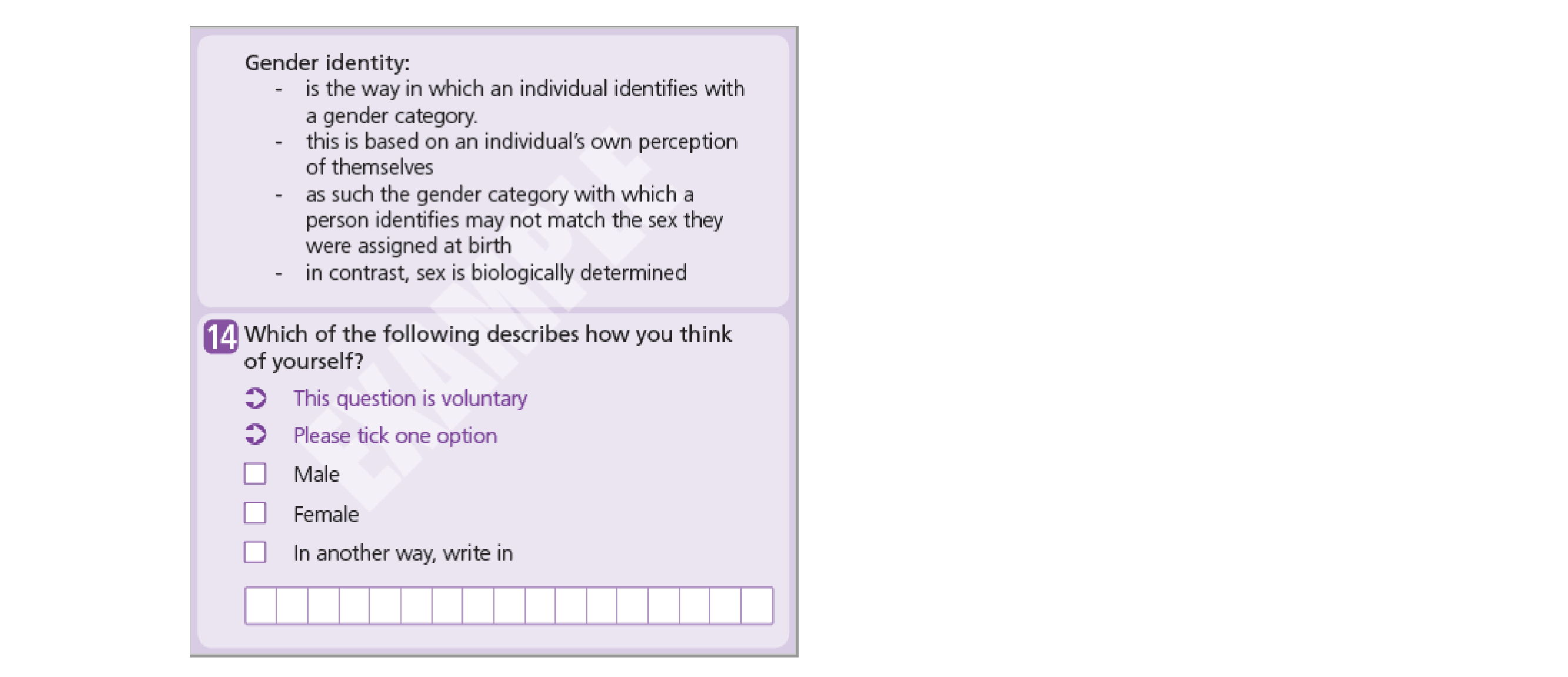

It is proposed that the prescribed aspect for gender identity will be trans status/history, and that this question would follow a non-binary sex question.

While the development and testing of the Census questions continues, the inclusion and wording of questions will be subject to the Scottish Parliament's approval.

There are no direct costs attributable to the Bill.

Introduction

The Scottish Government intends that questions on prescribed aspects of gender identity and sexual orientation will be included in Census 2021. The detail of these questions will be provided in a Census Order1.

The Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill (‘the Bill’) was introduced by the Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Tourism and External Affairs, Fiona Hyslop MSP, on 2 October 2018.

The main aim of this short Bill is to ensure that, if questions are added to the Census on prescribed aspects of gender identity and sexual orientation, answering them will be voluntary.

It is proposed that the prescribed aspect for gender identity will be trans status/history, and that this question would follow the sex question.

This briefing sets out some context on sexual orientation and gender identity. It considers the aim of the Census, the extensive research and consultation on question development for Census 2021, the need for equality information, and the provisions in the Bill.

Context

The Census is the most comprehensive source of equality data in Scotland1. Sample surveys of the population are not able to adequately capture small population groups. Census data, on the other hand, allows for analysis by equality group and by small geographic areas. The information on equality groups in the Census can be used to monitor discrimination and to plan public services.

While the Census covers most equality groups, it has not in the past included questions about sexual orientation or gender identity. The move to include such questions probably reflects changing social attitudes around sexual orientation and gender identity.

Sexual orientation

Terminology

The Policy Memorandum accompanying the Bill describes sexual orientation as:

...a combination of emotional, romantic, sexual or affectionate attraction or feelings towards another person. How a person determines their sexual orientation can be based on any combination of the above attractions, feelings or behaviours. It can change over time and a person may not know what their sexual orientation is.

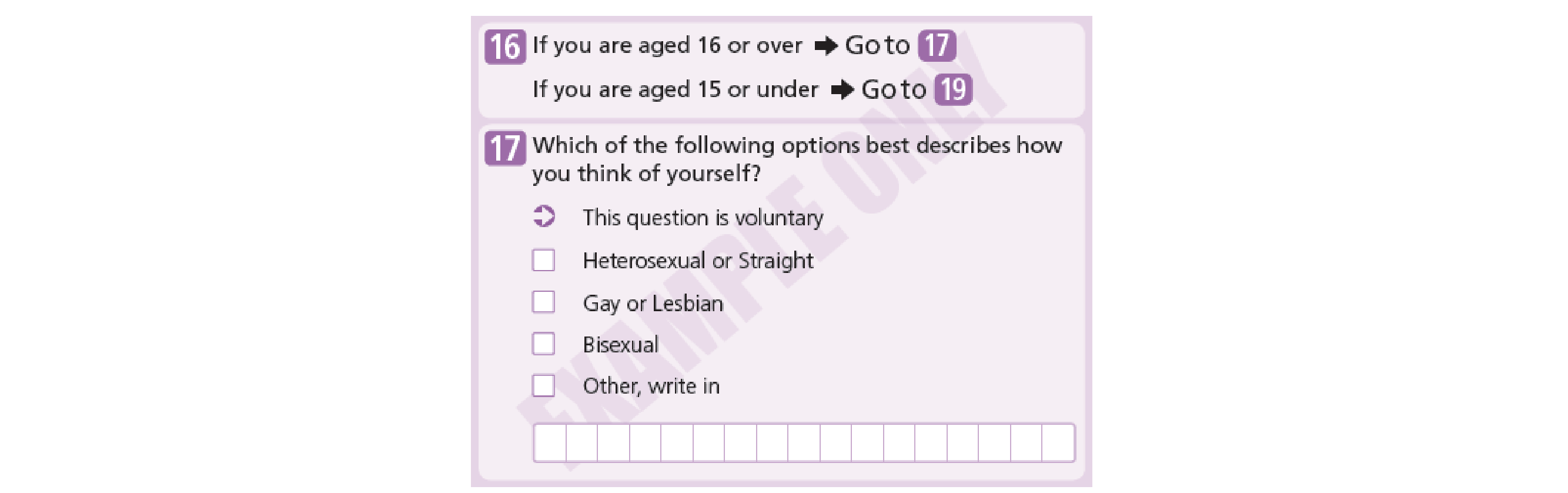

The intention of the Bill is to mirror the existing question commonly used in surveys in Scotland which use the following terms:

Heterosexual / Straight

Gay / Lesbian

Bisexual

Other

Changing attitudes and legislative change

Discriminatory attitudes towards same-sex couples have mitigated over time. While in 2000, 48% of the Scottish population said that sexual relations between two adults of the same sex is ‘always wrong’, only 18% of people in Scotland expressed this view in 20151.

Reflecting changing public attitudes, legislation has been introduced in recent years with the aim of bringing about equality for same-sex couples on the same basis as opposite sex couples. Legislation has also had a positive effect in promoting equality and changing discriminatory attitudes.

Same-sex sexual activity between men was a criminal offence in Scotland until 1980, when it was decriminalised for men over the age of 21i. The age of consent for sex between men was further reduced from 21 to 18 in 1994ii, and then to 16 in 2001iii. This equalised the age of consent with that for opposite sex sexual activity. It is worth noting that consensual same-sex sexual activity between women was never criminalised in Scotland.

The Scottish Parliament recently passed the Historical Sexual Offences (Pardons and Disregards) (Scotland) Act 2018 which:

pardoned those convicted of criminal offences for engaging in same-sex sexual activity which is now legal; and

provides a process for such criminal offences to be disregarded and removed from police records.

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 allowed same-sex couples to register their civil partnership which was similar, but not identical, to marriage. To bring further equality, the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014 made marriage available to same-sex couples.

Gender identity - trans status/history

Terminology

The NRS is currently working with the following definition of trans:

Trans is an umbrella term for anyone whose gender identity or gender expression does not fully correspond with the sex they were assigned with at birth1.

The Policy Memorandum2 uses the definition of trans given below. Note, however, that 'intersex' is no longer included in this definition1:

The term 'trans' in the proposed question refers to a diverse range of people who find their gender identity does not fully correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth. Transgender people may or may not experience the medical condition of gender dysphoria/dissonance. They may or may not have completed a process of gender reassignment. The umbrella term 'trans' can include trans women, trans men, non-binary gender people, people who cross-dress and intersex people. Consultation with stakeholders supported the use of 'trans' in the actual question rather than 'transgender'. This question falls with gender identity, which refers to the internal sense of who we are, and how we see ourselves in gender terms, being male, female, or somewhere in between/beyond these identities.

Changing attitudes and legislation

Research on Attitudes to Discrimination and Positive Action4 suggests that discrimination towards people who cross-dress or have undergone gender reassignment is reducing over time.

People were asked in 2015, if they would be happy or unhappy if a close relative married or formed a long-term relationship with:

someone who cross-dresses - 39% said they would be unhappy (down from 55% in 2010).

someone who has undergone gender reassignment - 32% said they would be unhappy (down from 49% in 2010).

It has been suggested that the decline in discriminatory attitudes towards trans people is related to a longer-term decline in discriminatory attitudes towards lesbian and gay people4:

This appears to be, in part, related to a longer-term decline in the prevalence of discriminatory attitudes towards lesbian and gay people. Those who said that same sex relationships were ‘rarely’ or ‘not at all wrong’ were not only much less likely to say that they would be unhappy about a close relative marrying someone of the same sex, but were also much less likely to say they would be unhappy about a relative marrying someone who cross-dresses or who has undergone gender reassignment.

Gender Recognition Act 2004

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) is UK wide legislation which provides a mechanism for trans people to apply for legal recognition in their acquired gender. The GRA established the Gender Recognition Panel, made up of legal and medical members. The Panel makes decisions on the issuing of gender recognition certifications. Before issuing a certificate, the Panel must be satisfied that the person applying:

Has, or has had, gender dysphoria; and

Has lived in the acquired gender for two years before the date of the application

Gender dysphoria is described in the General Guide for all Users: Gender Recognition Act 2004 (HM Courts and Tribunals Service) as:

…a recognised medical condition variously also described as gender identity disorder and transsexualism. It is an overwhelming desire to live in the opposite gender to that which a person has been registered at birth.

There is no requirement under the GRA for an applicant to undergo surgery, sterilisation or hormone therapy .

Once someone has been successful in changing their gender they will be issued with a new birth certificate.

The Scottish and UK Governments have each undertaken a consultation as part of a review of the GRA:

The Scottish Government consulted on a review of the Gender Recognition Act 2004, between 9 November 2017 to 1 March 2018. It has received 15,967 responses, 15,532 from individuals and 165 from organisations.

The UK Government consulted on the Gender Recognition Act 2004 between 3 July until 22 October 2018. It has received over 53,000 responses.

Many trans people are put off the current process because it is "intrusive, costly, humiliating and administratively burdensome"6. Both governments have sought views on simplifying the process by creating a statutory self-declaration process.

Between April 2005/06, when the Gender Recognition Act 2004 came into effect, and June 2018,5,000 gender recognition certificates have been granted7. However, this does not necessarily reflect the number of trans people in the UK. The UK Government tentatively estimates that there are between 200,000 and 500,000 trans people in the UK8. This is based on applying estimates of population prevalence from studies in other countries which suggests that between 0.35% and 1% of the UK population might be trans, although this does not include people who identify as non-binary9.

There has been much debate regarding the ability of trans people to self-identify. One aspect of this debate focuses on men who might self-identify as women for nefarious purposes and would pose a threat to women, particularly in single-sex spaces, such as women's refuges and women's prisons. There are existing safeguards in the Equality Act 2010 for single-sex services which allow service providers to exempt a trans person from a service, but there must be a legitimate reason for doing so (schedule 3, part 7). However, some dispute the utility of this exemption.

The Equality Act 2010 (s.7) provides protection from discrimination for people with the protected characteristic of 'gender reassignment'. This definition is broad enough to include trans people with and without a gender recognition certificate:

7. (1) A person has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment if the person is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person's sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex.

(2) A reference to a transsexual person is a reference to a person who has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment.

(3) In relation to the protected characteristic of gender reassignment—

(a) a reference to a person who has a particular protected characteristic is a reference to a transsexual person;

(b) a reference to persons who share a protected characteristic is a reference to transsexual persons.

The Equality Act 2010 refers to ‘sex’ in binary terms – 'man' or 'woman' (s.11). It defines ‘woman’ as ‘female of any age’, and ‘man’ as ‘male of any age’ (s. 212(1)). The use of 'sex' in these definitions is generally understood in the biological sense.

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 allows people to legally change their gender. This means that a person who was born biologically male can legally become a woman while a person who was born biologically female can legally become a man.

Therefore, in law, a woman is either biologically female, or is someone who has legally changed their gender to be a woman, and vice versa for men.

The Scottish Government has now published the analysis of its consultation on the Gender Recognition Act 200410. The majority of respondents, 60% of those answering the question, agreed with the proposal to introduce a self-declaratory system for legal gender recognition. A majority of respondents, 62% of those answering the question, thought that Scotland should take action to recognise non-binary people.

Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018

The Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018 aims to improve the representation of women in non-executive positions on public boards. It introduced the 'gender representation objective' - a target that women should make up 50% of non-executive board membership. During its passage through the Scottish Parliament, the Bill was amended to include trans women in the definition of women, whether or not they have a gender recognition certificate. The definition in the 2018 Act reads:

'woman' includes a person who has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment (within the meaning of section 7 of the Equality Act 2010) if, and only if, the person is living as a woman and is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of becoming female.

What is the census?

The census is the official count of every person and household in Scotland. It is held every ten years and provides the most complete statistical picture of the Nation available. It also provides information that central and local government need to develop policies and to plan and run public services.

Scotland's census is taken by the National Records of Scotland (NRS) on behalf of the Registrar General for Scotland. The NRS is a non-ministerial department of the Scottish Government, established on 1 April 2011, following the merger of the General Register Office for Scotland (GROS) and the National Archives of Scotland (NAS).

The NRS's main purpose is to collect, preserve and produce information about Scotland's people and history and make it available to inform current and future generations. It holds records of the census of the population of Scotland from 1841and every 10 years after that. The one exception was the wartime year of 1941 when no census was taken. Census records are closed for 100 years under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002.

The plan for Census 2021 is that it will take place on Sunday 21 March, subject to Scottish Parliament approval, and will be conducted predominantly online1. The last census was conducted mainly on paper (80%), and 20% online.

The Census Act 1920

The Census Act 1920 ("1920 Act") provides for a census to be taken not less than five years after the previous census. The 1920 Act applies to Great Britain. In Scotland it is the duty of the Registrar General for Scotland to undertake the census, in accordance with the 1920 Act and any further Orders or regulations, under the direction of Scottish Ministers. In England and Wales, the responsibility rests with the UK Statistics Authority and is conducted by the Office for National Statistics.

The Schedule to the 1920 Act sets out the 'matters' that may be required by the census. The matters refer to the topic areas that people must provide answers to.

If a person refuses to answer a census question, or gives a false answer, they are liable to a fine not exceeding £1,000 (s.8). Currently, the only exception to this is the voluntary question on religion which was added by the Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2000. The 2000 Act specifically excludes penalising non-response to this question:

"But no person shall be liable to a penalty under subsection (1) for refusing or neglecting to state any particulars in respect of religion".

Every census requires subordinate legislation which provides detail on how a particular census will be run:

A Census (Scotland) Order will outline the date on which the census is to be taken; the persons by whom, and about whom, census returns are made; and the particulars to be stated in the returns. For Census 2021, the draft Order in Council is likely to be laid in the Scottish Parliament in late 2019.1

Census (Scotland) Regulations will set out detailed arrangements for how Scotland's Census 2021 will be conducted. These are likely to be laid in the Scottish Parliament early 2020.

A similar process will be followed in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, reflecting the importance of harmonisation and of carrying out the Census on the same day across the UK. Questions on sexual orientation are currently proposed for other parts of the UK and other census offices are also considering how best to meet user need in relation to data on gender identity.

Do we need a census?

The NRS1 explain why the census is needed:

For over 200 years, Scotland has relied on the census to underpin local and national decision making.

Around 200 countries worldwide now undertake a regular census under the UN census programme.

The census is the only survey to ask everyone in Scotland the same questions at the same time. It is unique in the provision of comprehensive population statistics.

It is used by central and local government, health boards, the education sector, the private sector, and the voluntary sector to plan and distribute resources that match people's needs.

The information collected must be "authoritative, accurate and comparable" for all parts of Scotland, and down to very small levels of geography. Only the census can consistently provide such information.

Basic information on population size, age, sex and location are crucial to work on pensions, migration, economic growth and labour supply.

Other information gathered helps governments to:

identify local housing demand and create housing supply

identify areas of deprivation, enabling them to target services

gather data on equality groups, enabling them to tackle discrimination Information on housing, household size and family make-up are crucial to policies on local housing demand and planning, and poor housing and overcrowding.

Census information is also used for a range of social and economic indicators:

population estimates

employment and unemployment rates

birth, death, mortality, and fertility rates

equalities data, such as age, sex, ethnicity, religion/belief and disability.

Census data is also used by local public services to meet local needs in health, education, transport, planning, and community care services.

NRS calculated the cost to health board funding allocations if the census was not carried out in 2011. If census figures from 2001 had been used to make population estimates and allocate funding to health boards, in 2014/15 there would have been misallocations of between £30m and £40m. Some health boards would have received more, some less, than their appropriate share.

Alternatives to the Census

In 2010, and before the 2011 Census, the UK Government's then Minister for the Cabinet Office, Francis Maude, said that the Census is an expensive and inaccurate way of measuring the number of people in Great Britain1.

The House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) undertook an inquiry in 2014 to look at the value and benefits of the 2011 Census and to consider the options for collecting population data in the future. The PASC said in their report that the Census needs to change, but that it is too soon to decide whether or not to scrap it2. The PASC heard from the National Statisticiani, who recommended that there should be a census in 2021, conducted online where possible, and that there should be greater use of administrative data and surveys. The PASC supported this view and said it was right to have a census in 2021 on the basis that alternative options had not been adequately tested and plans were not sufficiently advanced to provide a replacement3.

Following the 2011 Census, the NRS, in conjunction with the other UK Census offices, explored alternative ways to produce population statistics:

NRS had an open mind in identifying potential options and examined and compared various approaches to counting the population, both here and overseas, engaged with a diverse group of users, commentators and public bodies, and undertook qualitative and quantitative research into attitudes to the census and population statistics.

Having considered all the evidence, in March 2014, NRS recommended that a modernised 'traditional' census was the best way to meet users' needs. This would mean providing the 2021 census questionnaire online and supplementing the data collected with data held in administrative systems to improve the quality of information.

The need for information on equality groups

The Policy Memorandum refers to the Equality Act 2010, and in particular, the Public Sector Equality Duty, as a key reason for collecting information on sexual orientation and gender identity1. This view was also expressed during the census consultation process23 - public authorities need to collect information across the equality groups to fulfil the public sector equality duty.

Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 brought together over 100 separate pieces of legislation including the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Race Relations Act 1976, and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. The Act provides a range of protection from discrimination for nine "protected characteristics": age, religion and belief, race, disability, sex, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity, marriage and civil partnership, and gender reassignment. The aim of the Act was to simplify, harmonise and strengthen previous protections. The Act provides protection for the protected characteristics across employment, education, and goods, services and public functions.

Public Sector Equality Duty

Before the Equality Act 2010, there were three separate equality duties covering race, gender and disability, under the Race Relations Act 1976 (as amended), the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (as amended), and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

The Equality Act 2010 created the public sector equality duty, a single equality duty that incorporated the nine protected characteristics listed above.

The “general equality duty” came into force on 5 April 2011 and requires public authorities, and any organisation carrying out functions of a public nature, to consider the needs of protected groups, for example, when delivering services and in employment practices (s.149 Equality Act 2010). It incorporates all the protected characteristics, although marriage and civil partnership is only partially covered. The general duty requires public authorities to have due regard to the need to:

Eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimisation

Advance equality of opportunity between different groups

Foster good relations between different groups.

Section 153 of the 2010 Act gives Ministers in England, Wales and Scotland the power to impose “specific duties” through regulations. The specific duties are legal requirements designed to help public authorities meet the general duty. Each administration has developed the duty differently.

The Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties) (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (as amended) came into force on 27 May 2012. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in Scotland published guidance to support Scottish public authorities subject to the specific equality duties. Public authorities subject to the specific equality duties are required to:

report on mainstreaming the equality duty

publish equality outcomes and report progress

assess and review policies and practices

gather and use employee information

publish gender pay gap information

publish statements on equal pay

consider award criteria and conditions in relation to public procurement

publish required information in a manner that is accessible.

A key reason for requiring census data on gender identity and sexual orientation is to be able to fulfil the public sector equality duty. Census data would, for example, assist public authorities in carrying out equality impact assessments when they assess and review policies and practices.

Equality questions

The Census already collects information on a number of the protected characteristics. It includes questions about the protected characteristics of sex, age, disability, marriage and civil partnership, religion, and race. It does not ask questions about sexual orientation or gender reassignment.

There are some parallels with the questions on religion and ethnicity, and the proposed questions on sexual orientation. For example, religion is a voluntary question because it can be a sensitive and personal issue, and ethnicity includes small population groups.

The question on religion was introduced in the 2001 census, and its inclusion was allowed on the basis that answering it was voluntary. Consultation with users has shown that public bodies use the census information on religion to assist with monitoring discrimination, linked to the introduction of the public sector equality duty. The data has also been used to inform service provision for health, social care and education1.

A question on ethnic group has been asked since 1991, and has become one of the most widely used output variables. As well as meeting previous obligations under the Race Relations Act 1976 (as amended), and the Equality Act 2010, the data is used for resource allocation by central and local government. The NRS state that "Collecting this information in the census is particularly important because many ethnic groups in Scotland are too small in number to be captured effectively by sample surveys. The census gives the only robust information on size of groups at small area level"1.

Equality data gaps

The Scottish Government has identified evidence gaps across the protected characteristics. These are set out in Scotland's equality evidence strategy 2017-20211. The strategy does not define projects to fill these gaps. Rather, responsibility for addressing gaps in data and evidence will be shared across a range of organisations.

With regard to sex, gender identity and sexual orientation, the strategy states that:

Data on sexual orientation had improved in recent years. However, gaps persist, and official sources are likely to undercount the proportion of the population who are lesbian, gay or bisexual.

There is less evidence currently available on those who identify as transgender, including those who identify as non-binary.

There are also evidence gaps on intersex people.

Consultation for Census 2021

All societies change over time, so census questions have to be updated to reflect these changes. For Census 2011, five new questions were added, five were removed, and revisions were made to the existing questions.

Scottish Government bills usually follow an open consultation period with the public and interested parties before their introduction. However, the Census undergoes extensive consultation with the public and organisations to test public attitudes, gather information on user needs and to develop new questions. This process includes a consultation document, a range of stakeholder events, surveys and question testing.

The NRS held a Topic Consultation1 between 8 October 2015 and 15 January 2016. The consultation was published on the Scotland's Census website and the Scottish Government website, and was promoted through:

eight Scotland's Census newsletters to a distribution list of around 2000

via Scotstat, which is a network of users and providers of Scottish Official Statistics, with a distribution list of over 2,000 and

through tweets and updates to the Using Scotland's Census' Knowledge Hub.

A letter from the Registrar General was also sent to:

local authorities

health boards

Members of the Scottish Parliament

Scottish Parliamentary Committees

Scotland's Members of the UK Parliament

Scotland's Members of the European Parliament

In total, 113 responses were received, 91 from organisations and 22 from individuals2. The organisational responses by sector are shown below:

| Respondent type | Total respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % total respondents | |

| Individual | 22 | 19 |

| Organisation (all sectors) | 91 | 81 |

| Sector: | ||

| Academic or Research Institute | 5 | 5 |

| Local government | 16 | 18 |

| Private sector organisation | 4 | 4 |

| Representative body for professionals | 3 | 3 |

| Scottish Government and other public bodies (including executive agencies, NDPBs, NHS, etc) | 27 | 30 |

| Third sector/equality organisation | 27 | 30 |

| Other | 9 | 10 |

| Total responses | 113 | 100 |

Source: Table 1 Scotland's Census 2021 - Topic Consultation Report

The NRS use a set of evaluation criteria when assessing the need for a question on the Census. The key criteria are based on user requirements, such as strength of user need, suitability of alternative sources and the need for UK comparability. There are also considerations such as public acceptability, respondent burden, and data quality, as well as various operational requirements.

The NRS say that "Topics must carry a strong and clearly defined user need. A robust case must be made, or exist, for topics to be included in the 2021 Census"1. User need can be justified by, for example, improved service provision, or requirements from national or international legislation.

As in previous years, there will be three separate censuses in 2021. In addition to the Scottish Census, conducted by the NRS, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) will conduct the census for England and Wales, and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) will carry out the census in Northern Ireland. The three census offices work closely together to develop a set of questions that, wherever possible and necessary, will deliver harmonised outputs across the UK. The ONS has conducted its own work on gender identity, and sexual identity (it uses this term rather than sexual orientation) questions. The NISRA received responses on sexual identity in its topic consultation, but there is no reference to any comments on gender identity. The ONS and NISRA have not published recommendations to date.

To ensure data quality, information should not be collected if it is not reliable, or causes difficulty for people to answer accurately. Consideration must be given to whether sensitive or potentially intrusive questions should be asked that may have a negative impact on the response rate. Questions should not impose an excessive burden on respondents, for example, through lengthy instructions, or large numbers of questions on a single topic.

The focus of the Topic Consultation was on the information required at topic-level, rather than the detail of the questions that should be in the census. The Topic Consultation did not specifically ask about the need for a question on gender identity. However, the research and consultation undertaken by NRS, "clearly identified a user need for data on sexual orientation and gender identity, especially transgender status/history"4.

The next two sections cover the development of questions for sexual orientation and gender identity in more detail.

Sexual orientation

A question on sexual orientation was considered for the 2011 Census, but was not included. This was due to concerns around individual privacy and the public acceptability of including such a sensitive question in a compulsory household survey, and also concerns over the quality of the resulting data.

However, there is a well established user need for information on sexual orientation, which has led the Scottish Government to include a question on this in three major Scottish surveys:

The Scottish Household Survey

The Scottish Health Survey

The Scottish Crime and Justice Survey

The Topic Consultation sought views on whether to add a question on sexual orientation to the Census. There were 31 responses on this ; 11 from local authorities, 6 from the Scottish Government and other public bodies, and 7 from Third Sector/equality organisations1.

Support for the inclusion of a question on sexual orientation was given mainly for the following reasons: because sexual orientation is a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010and this data would help public authorities meet their monitoring and reporting duties; the information would also assist with Equality Impact Assessments, which inform policies and practices; the Equality and Human Rights Commission also need to use the information in a statutory review every 5 years.

Other requirements noted included a need to undertake analysis of sexual orientation in relation to other characteristics, as well as the need for data below local authority level. The Scottish surveys listed above do not allow for information below local authority level, or for disaggregation by other characteristics.

A number of respondents recognised the sensitive nature of the question, but also that public attitudes had changed considerably since the planning for the 2011 Census.

Based on the strength of user need, the NRS concluded that further work was required on this question, including public acceptability testing. This would help inform the decision on whether a question on sexual orientation should be recommended for inclusion in the 2021 Census.

Ipsos MORI was commissioned to undertake public acceptability testing for the sexual orientation topic for all three UK census offices.

The testing found that 63% of people in Scotland considered the question acceptable, with 15% saying that it was not acceptable. Views varied with age as indicated below.

| Age | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: All participants | 86 | 117 | 192 | 256 | 273 | 210 |

| Very acceptable | 34% | 26% | 27% | 24% | 17% | 12% |

| Acceptable | 47% | 44% | 35% | 34% | 36% | 32% |

| I am undecided | 15% | 20% | 21% | 18% | 17% | 20% |

| Not acceptable | 2% | 4% | 9% | 13% | 11% | 16% |

| Not at all acceptable | 2% | 7% | 7% | 8% | 16% | 14% |

| Not stated | - | - | 1% | 2% | 3% | 6% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Table A2: Scotland's Census 2021 - Sexual Orientation Topic Report

However, 78% of respondents said they would answer the question accurately if it was included in the 2021 Census. Of those who would not answer the question, the majority would skip it and continue completing the rest of the form.

ScotCen Social Research was commissioned in 2017 to conduct cognitive and quantitative testing of selected questions for Scotland's Census 2021. Cognitive testing is a form of in-depth interviewing with a small number of respondents. Quantitative testing is undertaken to identify data concerns.

This cognitive testing found that all participants were able to answer the question, and almost all found it acceptable and clear. A small number described the question as unclear, and therefore difficult to answer. While all participants were able to give an answer, some wanted the ability to tick more than one response. For other members of the trans community, "not having a fixed, binary understanding of gender made labelling their sexual orientation difficult."

The qualitative testing found that almost all participants provided a valid response to the question on sexual orientation. The question was voluntary, and 9% of participants chose not to answer.

Overall, the consultation and research evidence indicate that the question on sexual orientation is acceptable to the public and that the majority of people would provide a valid response.

Gender identity

A user need for a question on gender identity was identified in the course of the Topic Consultation.

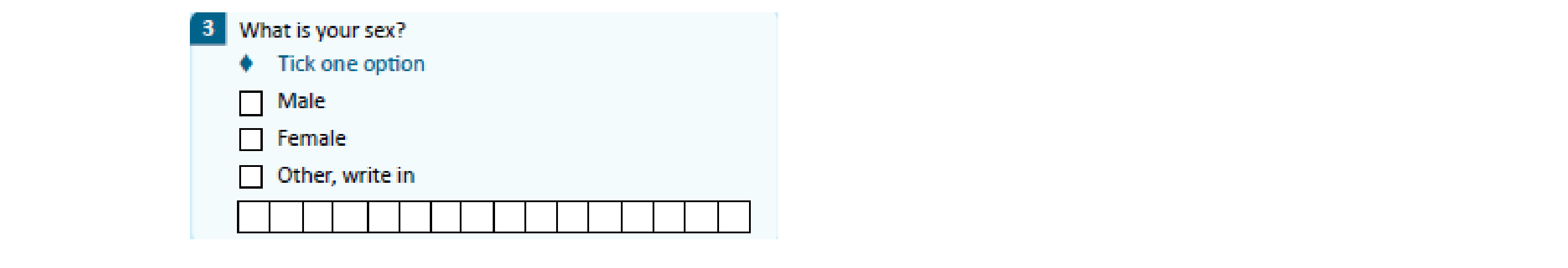

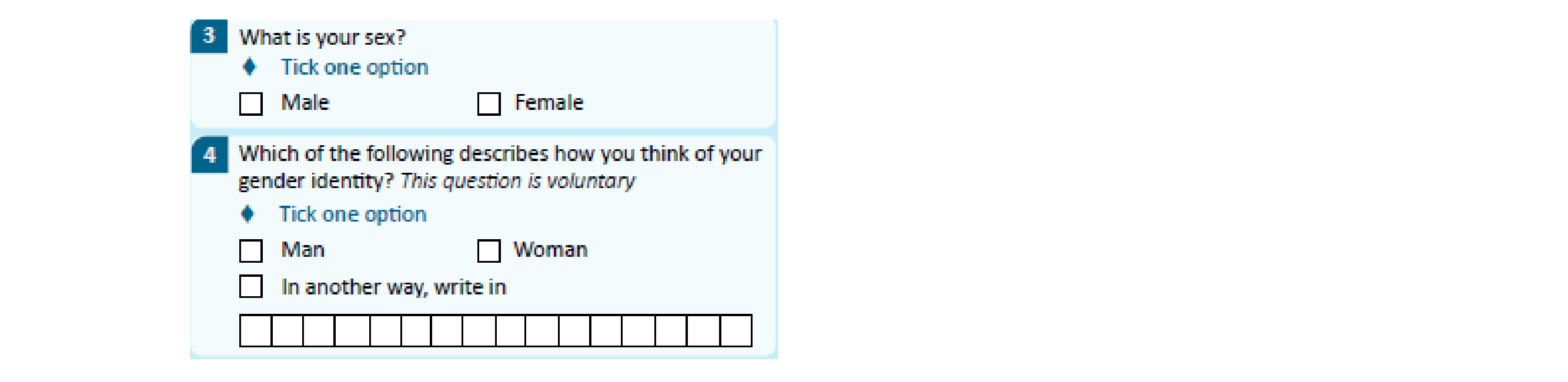

It is proposed, therefore, that a gender identity question will follow the sex question on the Census. It is also proposed that the sex question for Census 2021 be non-binary.

Sex question

As NRS point out, sex is a key demographic variable and, since 1801, the Census has collected data on the number of males and females resident in Scotland. There is a strong user need for this variable; it is a vital input to population, household and other demographic statistics which are used by central and local government to inform resource allocation, target investment, and to carry out service planning1. Sex is also a protected characteristic in the Equality Act 2010.

The sex question in the 2011 Census was a binary self-identified sex question.

Online guidance for the 2011 Census said that trans people could select the option for how they identify, irrespective of the details on their birth certificate. The guidance stated:

I am transgender or transsexual. Which option should I select? If you are transgender or transsexual, please select the option for the sex that you identify yourself as. You can select either ‘male’ or ‘female’, whichever you believe is correct, irrespective of the details recorded on your birth certificate. You do not need to have a Gender Recognition Certificate.

If you are answering for someone who is transgender or transsexual then where possible you should ask them how they want to be identified. If they are away, you should select the sex you think they would wish to be identified as. You can select either ‘male’ or ‘female’, irrespective of the details recorded on their birth certificate. You do not need to know if they have a Gender Recognition Certificate.

A respondent need for changing the sex question was identified at a stakeholder event on sexual orientation and gender identity in January 2017. The binary nature of the 2011 question does not allow non-binary people to answer the question truthfully.

A non-binary self-identified sex question allows those who do not identify as either male or female to tick a third response option and write in how they identify. People who are trans are also able to tick the response option for how they identify rather than their having to disclose their sex assigned at birth e.g. a trans man may self-identify as male.1

Gender identity and Trans status/history

The Explanatory Notes accompanying the Bill describe gender identity as:

...our internal sense of who we are, and how we see ourselves in regards to being a man, a woman, or somewhere in between/beyond these identities.

There has never been a question on gender identity in the Census. However, the recent Topic Consultation highlighted a strong user need for including such a question in the 2021 Census. This is because gender reassignment is a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010 and public authorities require information on this demographic variable to fulfil their duties under the Act. A reliable data source on the size and locality of the trans population will also help develop policy to meet the specific needs of this group. Because the trans population is small and distributed widely across Scotland, it is likely that the Census is the only source that would be comprehensive enough to provide accurate information1.

Public acceptability

Ipsos MORI carried out public acceptability testing of a gender identity question for the three census UK offices between January and March 2017.

The Ipsos-MORI survey found that 77% of the general public in Scotland considered it acceptable to ask a question on gender identity, with only 8% saying it was unacceptable. The majority, 84%, said they would answer the question accurately if it was included in the 2021 Census. In the context of providing an answer on behalf of another household member aged 15 or under, the proportion of those who thought it unacceptable rose to 16%. The age of respondents also affect views on acceptability; older people were less likely than younger people to find the question acceptable.

| Age | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: All participants | 59 | 116 | 186 | 240 | 274 | 215 |

| Very acceptable | 52% | 43% | 48% | 38% | 31% | 22% |

| Acceptable | 31% | 36% | 37% | 44% | 38% | 48% |

| I am undecided | 12% | 17% | 9% | 10% | 15% | 10% |

| Not acceptable | 4% | 1% | 3% | 4% | 6% | 6% |

| Not at all acceptable | 1% | 1% | 3% | 2% | 6% | 6% |

| Not stated | - | 1% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 8% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Table A3: Scotland's Census 2021 - Sex and Gender Identity Topic Report

Quantitative testing

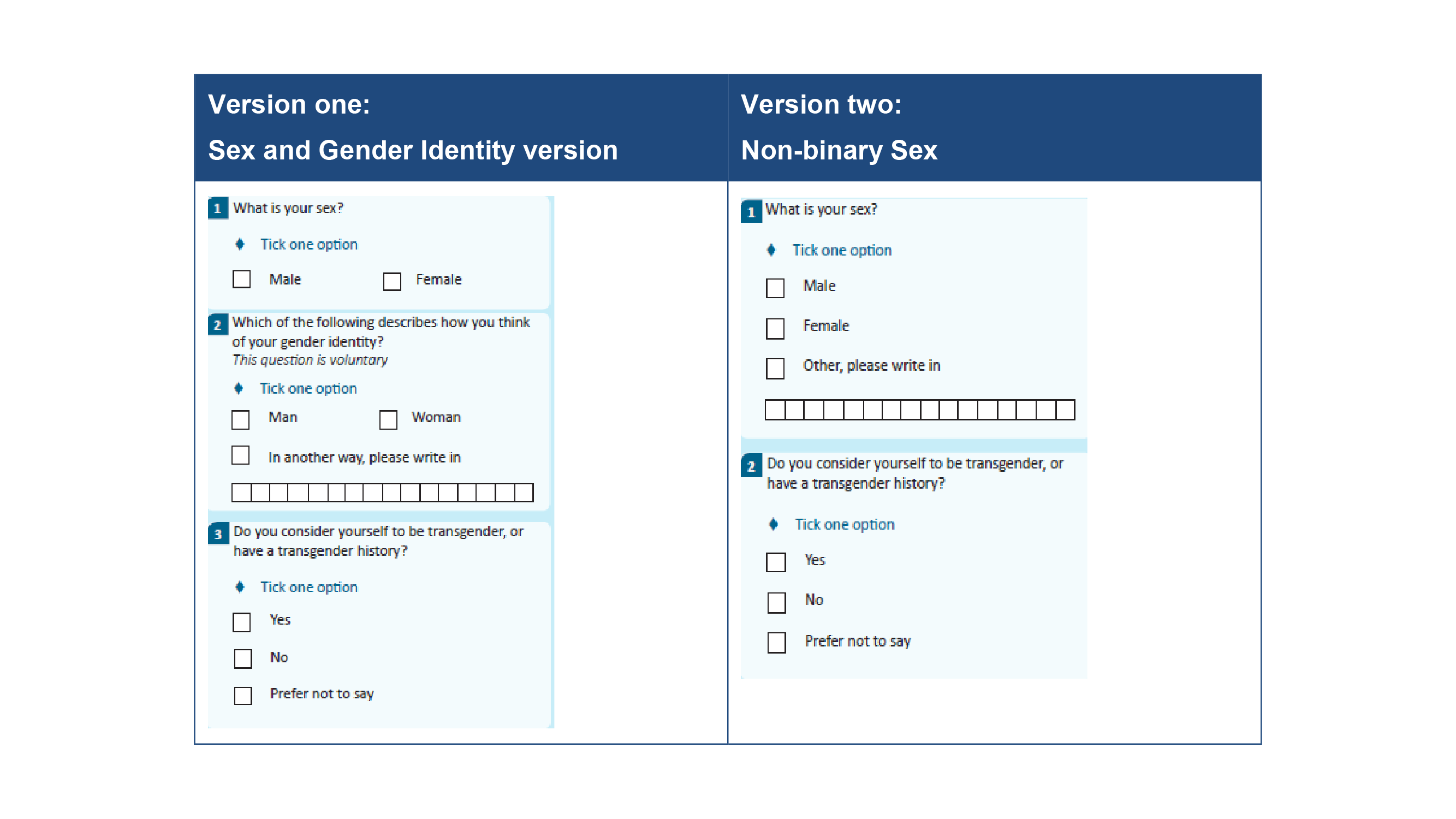

Between June and August 2017, Ipsos MORI carried out quantitative testing for the gender identity question for the three UK census offices. It tested three questions sets. The first asked a binary sex question, the second asked a non-binary sex question, and the third asked a binary sex question followed by a question about gender identity.

The testing found that there was a higher non-response rate when gender identity followed the sex question. The reasons for this were explored further in the cognitive testing, metioned earlier in this briefing and carried out by ScotCen in 2017 on behalf of the NRS.

Cognitive testing

The questions were tested with members of the trans community and members of the general population. Findings included that:1

Respondents had different understandings of the term sex. Some assumed sex referred to 'biological sex' or 'assigned sex at birth', whereas others saw the term as having the same meaning as gender, and could refer to the sex they 'self-identified' with.

Respondents' understanding of the term ‘sex’ appeared affected by both their prior conceptions of the term, and the other questions asked. Having a separate question on gender identity may have reinforced the notion that ‘sex’ refers to biology, whereas ‘gender’ refers to identity.

Respondents’ interpretation of the term sex directly impacted on perceived acceptability of the questions in trans respondents. Interpretation of the term sex also impacted on these respondents’ ability to provide an answer. Some trans respondents objected to providing their biological sex or assigned sex at birth (although this was not the intended meaning of the question).

Issues were raised with the binary sex question by some respondents. Some respondents felt that a ‘Male/Female’ response was not sufficient.

There were no objections to the inclusion of a question on gender identity in the Census; there were, however, concerns about using a question on gender identity in combination with a binary question on sex.

Further quantitative testing

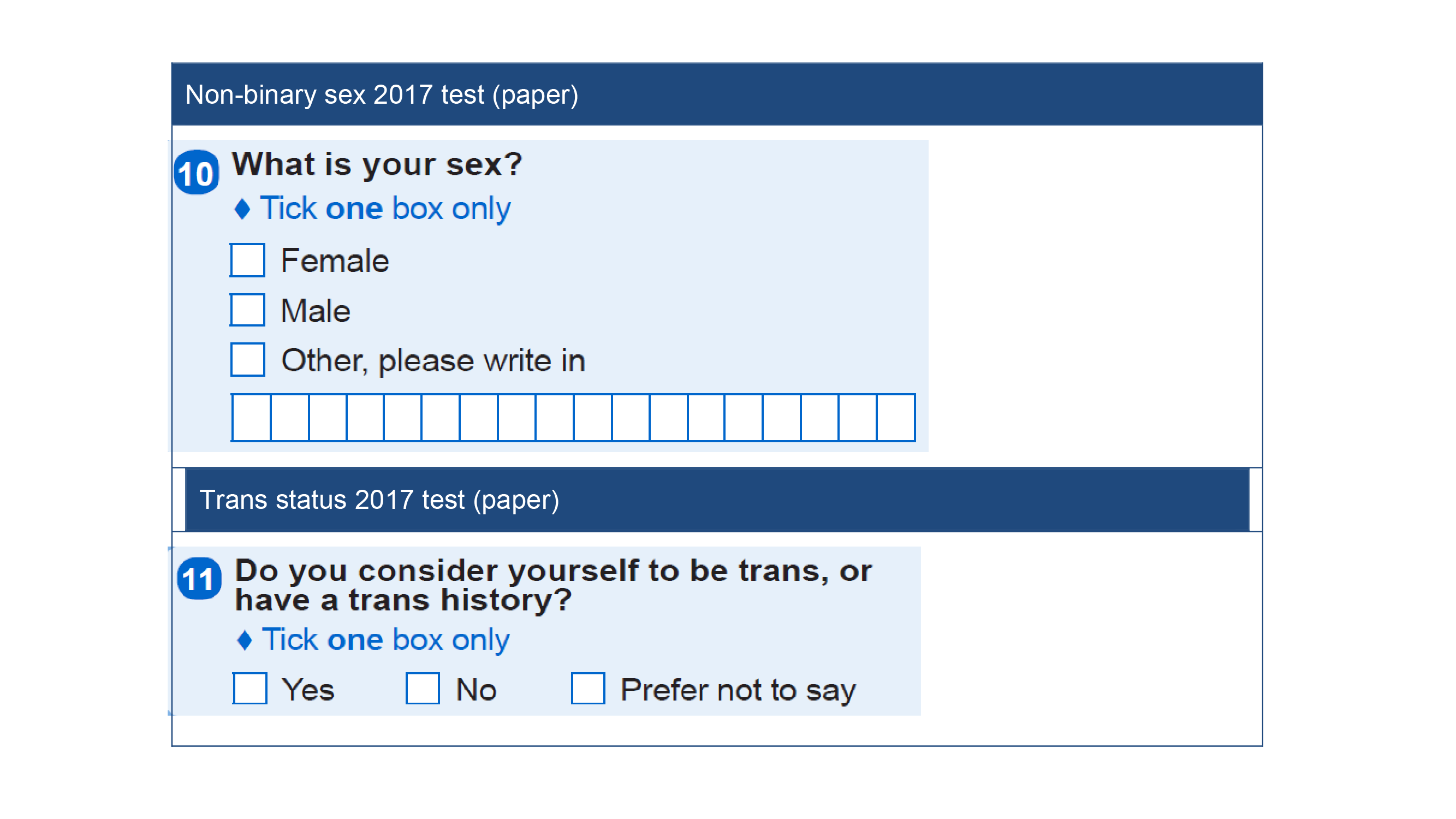

Following this, further quantitative testing was carried out on a non-binary sex question followed by a trans status question.

Testing found that a question on sex, followed by a question on trans status, can produce good quality data and meet user needs.

Next steps

Further testing is being undertaken on the inclusion of the write-in boxes in sex and trans status questions, along with further development of alternatives to 'Other' terminology.

What does the Bill do?

The aim of the Bill is to amend the Census Act 1920, to make answering questions on prescribed aspects of gender identity - trans status/history, and on sexual orientation, voluntary.

The schedule of the 1920 Act lists the topics that people may be required to give answers on. These are referred to as 'matters' in the 1920 Act - 'Matters in respect of which particulars may be required':

1. Names, sex, age.

2. Occupation, profession, trade or employment.

3. Nationality, birthplace, race, language.

4. Place of abode and character of dwelling.

5. Condition as to marriage or civil partnership, relation to head of family, issue born in marriage.

5A. Religion.

6. Any other matters with respect to which it is desirable to obtain statistical information with a view to ascertaining the social or civil condition of the population.

The Bill:

adds references to gender identity and sexual orientation in the schedule

in paragraph 1, after 'sex' it will add '(including gender identity)'

'sexual orientation' will be added after paragraph 5A, as 5B

amends section 8 (1A) of the 1920 Act to put particulars about sexual orientation, and enable prescribed particulars about gender identity to be put in the same category as religion, so that no-one will be fined for not answering questions on these matters. This makes the questions on gender identity and sexual orientation voluntary

The Policy Memorandum1 states that the Scottish Government regards 'gender identity' as already being covered by the reference to 'sex' as one of the 'matters' in paragraph 1 of the schedule in the 1920 Act. It states that a question about gender identity could be asked without the need for an amendment to the 1920 Act. It also considers that paragraph 6 of the schedule is broad enough to facilitate inclusion in the Census of a question on sexual orientation.

The main policy aim of the Bill is not, therefore, to facilitate the asking of questions about gender identity and sexual orientation but to make answering those questions voluntary. The policy recognises both the importance and sensitivity of the new questions and seeks to mitigate concerns about intrusion into private life by placing the questions on a voluntary basis.

Section 1(3) of the Bill ensures that a question on sexual orientation, as with religion, would be voluntary. In terms of gender identity, a power is provided to prescribe aspects of gender identity, such as trans/trans history, for the purposes of making those questions voluntary. The reason for this approach on gender identity is to ensure that the Bill "does not hard-wire provision that would make answering questions about gender identity voluntary (that might catch the sex question).1"

Alternative approach

An alternative approach to achieve the same objective would have been to use a 'prefer not to say' option for the sexual orientation and gender identity questions. This approach would not require an amendment to the 1920 Act. Failing to provide a response would still be an offence, but this approach would allow a person to avoid disclosing their sexual orientation or trans status. However, it was not considered acceptable to compel people to specifically answer these questions. "The 'prefer not to say' option was not considered to provide enough clarity on the voluntary nature of the questions that the policy intends. Compelling individuals to respond in some way would not achieve the policy aim."1

Costs

There are no direct costs attributable to the Bill. This is because the Bill enables questions on sexual orientation and trans status/history to be voluntary, but does not require the questions to be asked.

The Financial Memorandum1 does set out the costs of the Census, which is briefly set out here.

The overall cost of the 2021 Census over the 10 years of development and operation, between 2015/16 and 2024/25 is estimated to be around £100m. The cost for question development, capturing and coding responses, and the processing of data, is estimated to be £10m. On the basis that there are 59 questions currently proposed for the 2021 Census, this amounts to £170,000 per question. This would equate to around £340,000 for inclusion of the two questions on sexual orientation and trans status.

The figure of £340,000 is considered a maximum value, given that the questions are to be voluntary. However, there is the possibility that asking such sensitive questions leads to an increase in requests for individual internet access codes or questionnaires, rather than household ones. The NRS has no estimate of the likely scale of such requests or any additional costs that might be incurred.

Additional costs were incurred for question testing. There was a full set of cognitive and quantitative testing on all of the questions, which cost a total of £127,000. This covered 22 question topics - gender identity and sexual orientation were covered as one topic which means the cost for testing this topic was around £6,000. There was also public acceptability testing on the two questions. This work was shared with the other UK Census offices, and the Scottish share of costs was £40,000.

Therefore, the total spend so far on developing the sexual orientation and gender identity questions is around £386,000.