The UK's Departure from the European Union - An overview of the Withdrawal Agreement

This briefing provides an overview of the Withdrawal Agreement reached between the EU and the UK Government which was endorsed by the European Council on 25 November 2018. If ratified, the Withdrawal Agreement will facilitate the UK's departure from the EU on 29 March 2019 in an orderly fashion.This briefing examines the Withdrawal Agreement from a Scottish perspective.

Executive Summary

On 29 March 2017, the UK Government notified the European Council of the UK's intention to withdraw from the European Union. The withdrawal process is set out in Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU).

The withdrawal negotiations focussed on four key priorities which were citizen's rights; avoiding a legal vacuum in the trade of goods; a financial settlement and the Ireland and Northern Ireland border.

After around 18 months of negotiations, EU leaders endorsed the Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union at a special meeting of the European Council on 25 November 2018. If ratified, the Withdrawal Agreement will facilitate the UK's departure from the EU on 29 March 2019 in an orderly fashion.

The Agreement includes governance arrangements including the establishment of a Joint Committee, dispute resolution procedures and the role of the European Court of Justice.

Provision is also made in the Agreement for a transition period to the end of 2020 which effectively means the UK will continue to operate as if it were an EU Member State, though without participating in the EU's decision making processes. There is also an option to extend the transition period by a further one or two years.

On citizens' rights the Agreement largely protects the existing rights of EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in the EU. The agreement also sets out procedures for ensuring that processes which are ongoing as the transition period ends will be able to be concluded in areas such as police and judicial cooperation and public procurement.

Given the red lines of the EU and the UK, the hardest negotiating issue to reach agreement on was how ensure that when the UK leaves the EU, trade across the Ireland and Northern Ireland border will continue to operate as freely as it currently does, in line with the principles of the Good Friday Agreement, without any physical infrastructure at the Irish land border. This issue has been addressed in the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland which introduces a "backstop".

The Protocol makes clear that the backstop is "not the preferred or expected outcome" with the UK Government suggesting it still hopes to negotiate a future relationship which means the backstop is never required. Linked to this aspiration is the ability to extend the transition period if necessary and desirable rather than invoke the backstop.

Article 1 of the Protocol also makes clear that the backstop arrangement should not be seen as creating a permanent relationship between the UK and the EU and that it is only intended to apply temporarily (if at all) unless and until it is superseded.

The Ireland and Northern Ireland Protocol proposes an EU-UK wide customs arrangement. The Protocol sets out the arrangements for ensuring the avoidance of a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland as a result of Brexit. These include provision for Northern Ireland to continue to abide by the EU's Customs Code and relevant Single Market in goods legislation to ensure free movement of goods across the Ireland and Northern Ireland border. This approach will however mean that there will need to be checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK.

If the backstop contained in the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland is ever introduced, it will mean Northern Ireland has a different relationship with the EU compared to the rest of the UK. This will be as a result of Northern Ireland's alignment to the Single Market in goods.

The Scottish Government has suggested that Northern Ireland's potential direct access to the Single Market in goods will give it a competitive advantage within the UK.

Context

On 25 November 2018, a meeting of the European Council endorsed the Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community (the Agreement). At the same time, a Political Declaration on the future relationship was also endorsed. The Political Declaration will be the subject of a further SPICe Briefing.

If ratified, the Withdrawal Agreement will facilitate the UK's departure from the EU on 29 March 2019 in an orderly fashion.

Writing on the Centre on Constitutional Change blog, Professor Nicola McEwen summarised the importance of the draft Withdrawal Agreement from the perspective of the devolved nations:

Commitments made in the Withdrawal Agreement will have both direct and indirect effects for the responsibilities of the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales. The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland – the backstop to be introduced in the absence of a negotiated deal on the future relationship – includes a single customs area for the UK and the EU, but effectively embeds Northern Ireland within the EU single market, an outcome the Scottish Government has argued puts it at a competitive disadvantage. The backstop agreement also commits the UK to maintain minimum common standards ‘with the aim of ensuring the proper functioning of the single customs territory’, including in large swathes of environmental policies, employment policies and state aid, with independent oversight and enforcement. Many of the areas noted in the Agreement fall within devolved competence.

McEwen, N. (2018, November 19). The Withdrawal Agreement and Devolution. Retrieved from http://www.centreonconstitutionalchange.ac.uk/blog/withdrawal-agreement-and-devolution?utm_campaign=2234351_Centre%20on%20Constitutional%20Change%20newsletter%20-%20November%202018&utm_medium=email&utm_source=College%20of%20Arts%2C%20Humanities%20%26%20Social%20Sciences%2C%20The%20University%20of%20Edinburgh&dm_i=2MQP,1BW1B,77BCIH,4BTU0,1 [accessed 21 November 2018]

This briefing provides an overview of the content of the Agreement from a Scottish Parliament perspective, including areas which relate to devolved competences such as fisheries, environmental policy, justice and public procurement.

The briefing also focusses on some of the different elements of the agreement including citizens' rights, the role of the European Court of Justice and issues around the Ireland and Northern Ireland Protocol including the agreement of a differentiated relationship for Northern Ireland compared to the rest of the United Kingdom.

Background

On 29 March 2017, the UK Government notified the European Council of the UK's intention to withdraw from the European Union. The withdrawal process is set out in Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). Under the provisions within Article 50, if no agreement is finalised on the terms of the UK's departure from the EU it will leave automatically on 29 March 2019.

The Brexit Negotiations

The Withdrawal Agreement follows 18 months of negotiations after the UK Government notified the European Council of the UK's intention to withdraw from the European Union on 29 March 2017. The negotiations primarily focussed on the three issues of citizens' rights, financial settlement and the Northern Ireland and Ireland border.

The EU27 Negotiating Position

At the outset of the negotiations, the EU27 Member State Governments gave the European Commission's Chief Negotiator, Michel Barnier, a mandate to negotiate a Withdrawal Agreement, and a Political Declaration on the Future Relationship. The EU27's priorities for the negotiations were set out in a set of negotiating guidelines at the end of April 2017 and fell under 6 headings:1

Core principles

A phased approach to negotiations

Agreement on arrangements for an orderly withdrawal

Preliminary and preparatory discussions on a framework for the Union - United Kingdom future relationship

Principle of sincere cooperation

Procedural arrangements for negotiations under Article 50

The EU27 reaffirmed its commitment to keeping the UK as a close partner in the future and also to the principle that participation in the Single Market could not be conducted on a sector by sector basis. In relation to access to the single market the guidelines stated:

A non-member of the Union, that does not live up to the same obligations as a member, cannot have the same rights and enjoy the same benefits as a member. In this context, the European Council welcomes the recognition by the British Government that the four freedoms of the Single Market are indivisible and that there can be no "cherry picking". The Union will preserve its autonomy as regards its decision-making as well as the role of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

The four freedoms of the EU Single Market are the free movement of goods, services, capital and labour.

The guidelines also set out the EU27's commitment to a phased approach to the negotiations, with the priority being to reach agreement on the terms of the UK's withdrawal from the EU before detailed discussions about the future relationship could take place.

In the event, sufficient progress was made on the Withdrawal Agreement, the guidelines presented the opportunity for the start of discussions about the future relationship between the EU and the UK - though the EU was clear that the future relationship could not be finalised, ratified and come into force until the United Kingdom has left the EU.

Finally, the guidelines set out the the arrangements for the UK's orderly withdrawal from the EU and identified the EU27's priorities for the negotiations of the Withdrawal Agreement. The priorities broadly fitted under four headings:

Citizens' Rights

Avoiding a legal vacuum in the trade of goods

A Financial Settlement

The Ireland and Northern Ireland border

On 22 May 2017, the General Affairs Council of the European Union, meeting in its EU27 format (i.e. without the UK), adopted a decision authorising the opening of Brexit negotiations with the UK and formally nominated the European Commission as EU negotiator. The Council also adopted negotiating directives for the talks.2 These Directives recognised the same four priority headings for negotiation of the Withdrawal Agreement.

The Ireland and Northern Ireland border became the most difficult issue to address during the negotiations. At the outset, the negotiating directives given to the European Commission by the EU27 in relation to the Irish border said:

In line with the European Council guidelines, the Union is committed to continuing to support peace, stability and reconciliation on the island of Ireland. Nothing in the Agreement should undermine the objectives and commitments set out in the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts and its related implementing agreements; the unique circumstances and challenges on the island of Ireland will require flexible and imaginative solutions. Negotiations should in particular aim to avoid the creation of a hard border on the island of Ireland, while respecting the integrity of the Union legal order. Full account should be taken of the fact that Irish citizens residing in Northern Ireland will continue to enjoy rights as EU citizens. Existing bilateral agreements and arrangements between Ireland and the United Kingdom, such as the Common Travel Area, which are in conformity with EU law, should be recognised. The Agreement should also address issues arising from Ireland’s unique geographic situation, including transit of goods (to and from Ireland via the United Kingdom). These issues will be addressed in line with the approach established by the European Council guidelines.

The UK Government Position

Ahead of triggering the Article 50 process on 29 March 2017, the UK Government set out its negotiating position on Brexit through a speech by the Prime Minister and then in the form of a White Paper.

On 17 January 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May made a speech at Lancaster House in London in which she set out the UK Government's negotiating objectives for exiting the EU.1 The top line from the speech was that the UK will leave the Single Market.

The speech focussed on 12 objectives which were:

Provide certainty about the process of leaving the EU

Leaving the EU will mean laws will be made in Westminster, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast

Strengthen the Union between the four nations of the United Kingdom

Maintain the Common Travel Area with Ireland

Control of immigration coming from the EU

Rights for EU nationals in Britain and British nationals in the EU

Protect workers’ rights

Free trade with European markets through a free trade agreement

New trade agreements with other countries

The best place for science and innovation

Co-operation in the fight against crime and terrorism

A smooth orderly Brexit

On Single Market membership, the Prime Minister said:

This agreement should allow for the freest possible trade in goods and services between Britain and the EU's member states. It should give British companies the maximum freedom to trade with and operate within European markets - and let European businesses do the same in Britain.

But I want to be clear. What I am proposing cannot mean membership of the Single Market.

European leaders have said many times that membership means accepting the "four freedoms" of goods, capital, services and people. And being out of the EU but a member of the Single Market would mean complying with the EU's rules and regulations that implement those freedoms, without having a vote on what those rules and regulations are. It would mean accepting a role for the European Court of Justice that would see it still having direct legal authority in our country.

The UK Government followed up the Prime Minister's Lancaster House speech with the publication of The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union White Paper. The White Paper largely reiterated the UK Government's plans for Brexit.

In July 2018, the UK Government published its proposals for the future relationship. These have been referred to as the Chequers proposals because they were agreed by the UK Government during a cabinet meeting at the Prime Minister's country home at Chequers.

The Scottish Government's Brexit policy

From December 2016 to date, the Scottish Government has published six papers setting out its position on Brexit:

Scotland's Place in Europe, 20 December 20161

Protecting the rights of EU citizens: position paper, 17 July 20172

Scotland's place in Europe: people, jobs and investment, 15 January 20183

Scotland's Place in Europe: security, judicial co-operation and law enforcement, 14 June 20184

Scotland's place in Europe: our way forward, 15 October 20185

Scotland's place in Europe: science and research, 5 November 20186

Continuing membership of the Single Market and the Customs Union have been the constant theme in all of the Scottish Government's papers looking at Scotland's place in Europe.

The first paper, Scotland's Place in Europe, explained the importance of the European Single Market to Scotland and the possible use of European Economic Area (EEA) membership to remain within the Single Market. The paper examined the options for a differentiated proposal for Scotland retaining EEA membership whilst remaining part of the UK in the event of the UK Government leaving the EU.

The second paper, Protecting the rights of EU citizens, was a response to the UK Government's proposals on citizens' rights7. It reiterated the call for the UK to remain in the Single Market and a commitment to the free movement of persons.

The third paper, Scotland's place in Europe: people, jobs and investment, examined the economic impact of a number of different possible scenarios for the UK’s future relationship with the EU: continued single market membership, a preferential trade agreement and trading under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

The fourth paper set out the Scottish Government's position on the importance of maintaining a close relationship with the EU in relation to security, law enforcement and criminal justice. The aim of the paper was to help people understand how continued participation in the EU Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) criminal cross border justice and security measures benefits Scotland. The paper offered a "sectoral" insight into how a range of JHA measures currently work, why it matters and what is likely to be different after the UK leaves the EU.

In response to the UK Government's Chequers proposals for the future relationship8 which was published in July 2018, the Scottish Government published its fifth position paper, Scotland's place in Europe: our way forward. This paper explained why, in the Scottish Government's opinion, either a no-deal Brexit or a blindfold Brexit (where the UK leaves with no detail or guarantees on the future relationship) will be damaging. The Scottish Government again called for the UK to maintain its membership of the European Single Market and the Customs Union. If the UK Government reject that request then the Scottish Government called for an extension to the Article 50 period to allow for consensus to be agreed across the UK, thereby avoiding a "hurried and damaging exit". The Scottish Government also suggested that an extension would also allow time for another referendum on EU membership.

The latest position paper presents the Scottish Government's analysis of the implications for Scotland's science and research if the UK exits the European Union.

The Scottish Government have fully and unequivocally backed the Good Friday Agreement and supported the invisible border in Ireland, recognising the unique circumstances there. However, since 2016, it has argued that the UK Government should put forward a differential deal that reflects Scotland's remain vote, if the UK is to leave the single market. The Scottish Government sees this as being independent of any Northern Ireland border solution..

In his statement, on the proposed Withdrawal Agreement, on 15 November 20189, the Cabinet Secretary for Constitutional Relations told the Scottish Parliament:

the proposed deal does not meet the frequently stated Scottish Government requirement of single market and customs union membership for the whole of the UK, and so it fails for Scotland; does not make even a gesture towards recognising the vote of Scotland to remain; does not tackle the considerable and grave problems that will be caused by Scotland coming out of the single market and customs union; takes away the four freedoms, in particular the freedom of movement, which is essential for Scotland; and fails to address in any way the additional pressures on Scotland if its neighbour in Northern Ireland retains the advantages of single market and customs union involvement. It cannot therefore be supported by this Government or the Scottish National Party.

The Withdrawal Agreement

The Agreement between the EU and the UK finalised on 25 November 2018 focusses on the following areas:1

Protecting the rights of EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in EU27 Member States

A transition period until the end of December 2020 with the possibility of an extension

Separation issues that wind down certain arrangements (for example cooperation on civil court cases or procurement exercises still ongoing at the end of the implementation period) under the current EU legal order to ensure an orderly withdrawal

An agreed financial settlement ensuring both the UK and the EU honour the financial obligations accumulated whilst the UK was a member of the EU

Governance arrangements that provide legal certainty and clarity to citizens, businesses and organisations and respect the autonomy and integrity of both the UK’s and the EU's legal orders

A Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland (which is not intended to be permanent with the aim being it will be superseded by the future relationship) which includes:

In relation to the Ireland and Northern Ireland border, a legally operational backstop is to be available to ensure that there will be no hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. If the backstop is required, it will establish a Single Customs Territory between the UK and the EU to ensure the free flow of goods between Northern Ireland and Ireland. The Single Customs Territory will not apply to fishery and aquaculture products.

Arrangements to ensure Northern Ireland continues to apply elements of Single Market legislation to ensure goods can move freely between Ireland and Northern Ireland. This will mean businesses in Northern Ireland are able to access the EU Single Market as a whole without restriction.

A review mechanism.

Inclusion of level playing field measures applicable to the UK as a whole including on State Aid, competition, taxation, environmental standards and labour and social protection.

Establishment of a Joint Committee comprising representatives of the EU and of the United Kingdom. The Joint Committee will be responsible for the implementation and application of the Agreement. The EU and the UK may each refer to the Joint Committee any issue relating to the implementation, application and interpretation of the Agreement.

Dispute resolution

A Protocol on Gibraltar

The Common Provisions

The initial section of the Withdrawal Agreement provides for common provisions which will ensure the Agreement is correctly understood, operated and interpreted both in the EU and the UK.

Article 4 provides for the "methods and principles relating to the effect, the implementation and the application" of the Agreement. These effects include the principle of direct effect of EU law which would allow concerned parties (i.e. individuals, businesses, companies etc.) to invoke the Agreement directly before national courts in the UK and in EU Member States. This right is not time-limited and the UK has to ensure that its courts can "disapply" domestic legislation which is incompatible with the Agreement. Simply put, this means that UK courts will have to treat UK law which breaches the Agreement as not being valid or enforceable 1

UK courts will be required to follow case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) as it stands until the end of the transition period and "have due regard"i to case law of the ECJ handed down after the end of the transition period where it is relevant to the Withdrawal Agreement.

The Common Provisions provide that (with a few exceptions) all references to EU law in the Agreement should relate to EU law as it applies on the last day of the transition period. From an EU perspective this is to ensure that the provisions in the Agreement should clearly have the same legal effect in the UK as in the EU and its Member States2.

Governance of the Agreement

A crucial aspect of the Agreement concerns how it will be governed and enforced once it comes into effect.

Joint Committee

Title II of the Agreement establishes a Joint Committee which will be responsible for the implementation and application of the Agreement. The Joint Committee will be composed of representatives of the EU and of the UK.

Title II also sets out how the Joint Committee will operate. It will be co-chaired by both sides.

In terms of the operation of the Joint Committee, the Agreement states that either the UK or the EU may refer to the Joint Committee any issue relating to the functioning of the Withdrawal Agreement. The Joint Committee will then be empowered to make decisions and recommendations by mutual consent. The Agreement does not address what mutual consent within the Joint Committee means in practice.

The Joint Committee will meet at least once a year or by request of either the EU or the UK.

Beneath the Joint Committee, the Agreement includes provision for 6 sub-committees:

the Committee on citizens' rights

the Committee on the other separation provisions

the Committee on issues related to the implementation of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

the Committee on issues related to the implementation of the Protocol relating to the Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus

the Committee on issues related to the implementation of the Protocol on Gibraltar; and

the Committee on the financial provisions

The sub-committees are required to report to the Joint Committee both ahead of and following meetings. Further sub-committees can be established if deemed necessary.

Under the Agreement, the Joint Committee will have the power to adopt decisions in respect of all matters for which the Agreement provides and to make appropriate recommendations to the EU and the UK. Any decision adopted by the Joint Committee will be binding on the EU and the UK and so must be implemented. Decisions will have the same legal effect as the Withdrawal Agreement.

Annex VIII of the Agreement provides the rules of procedure for the Joint Committee and sub-committees.

Dispute Settlement

Title III of the Agreement sets out provisions for dispute settlement regarding the interpretation and application of the Withdrawal Agreement after the end of the transition period.

Initially, any dispute will be referred to the Joint Committee for further discussions. If after three months no agreement is reached, the Agreement includes a mechanism to establish an independent arbitration panel to rule on the dispute.

Exceptions to the Dispute Settlement mechanism: in the event the Ireland and Northern Ireland backstop (on which more later) is required, this will create a set of level playing field provisions applicable across the UK including common standards of environmental protections. Significant aspects of the level playing field provisions cannot be subject to the arbitration mechanism. These aspects are noted in the level playing field section.

The arbitration panel will be composed of five people, with two members proposed by the EU and two members proposed by the UK along with a chairperson who shall be selected by consensus by the four members of the panel.

Ahead of the end of the transition period, the EU and the UK must agree on a 25 person list of potential candidates to serve on an arbitration panel if necessary:

The Joint Committee shall, no later than by the end of the transition period, establish a list of 25 persons who are willing and able to serve as members of an arbitration panel. To that end, the Union and the United Kingdom shall each propose ten persons. The Union and the United Kingdom shall also jointly propose five persons to act as chairperson of the arbitration panel. The Joint Committee shall ensure that the list complies with these requirements at any moment in time.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756374/14_November_Draft_Agreement_on_the_Withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union.pdf [accessed 16 December 2018]

The rules of procedure governing the operation of the dispute settlement process are set out in Part A of Annex IX ("Rules of Procedure"). In addition, the Joint Committee will be responsible for keeping the functioning of those dispute settlement procedures under constant review and may amend the Rules of Procedure.

In the event a dispute concerns the interpretation of EU law, the arbitration panel must request a ruling from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) . The ECJ ruling will be binding on the arbitration panel.

If either the UK or the EU fails to comply with a ruling of the arbitration panel there is provision in the Agreement for a financial penalty to be imposed by the arbitration panel to be paid to the other party in order to incentivise compliance. The UK Government's explainer of the Agreement sets out what would happen in the event the fine is not paid:

If this is not paid, or if the offending party fails within a further six months to comply with the arbitration panel's ruling, then the complainant will be able to suspend in part or full the Withdrawal Agreement, except for the Citizens’ Rights part, or other agreements between the UK and the EU.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

The role of the European Court of Justice

The European Court of Justice (ECJ), based in Luxembourg, is the EU's highest legal authority.

It interprets EU law to ensure that it is applied in the same way in all Member States. National courts can make "preliminary references" to it requesting a ruling clarifying the law. Once the ECJ has ruled, the national court then decides the case.

It also settles legal disputes between national governments and EU institutions and can be used by individuals, companies or organisations to take action against EU institutions.

The role of the ECJ was part of Brexit campaigners aim to "take back control" and has also been part of the debate following the referendum. For example, in October 2016, the Prime Minister, Theresa May, declared at the Conservative Party Conference that, "we are not leaving [the EU] only to return to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice."

Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the ECJ retains its normal role within the transition period and can hear cases linked to the UK in this period.

However, the Withdrawal Agreement also provides a number of distinct roles for the ECJ after the transition period has ended. The main ones are outlined below:

Interpretation of EU law - If a dispute between the EU and UK on the Withdrawal Agreement has been submitted to arbitration and relates to the interpretation of EU law, the arbitration panel must request a ruling from the ECJ (Article 174(1)). Both the UK and EU will be able to make representations about the need for a reference and a hearing will take place if either party disagrees with the panel’s decision (Article 174(2)). The ECJ ruling will be binding on the arbitration panel (Article 174(1)). This role for the ECJ reflects the long-standing position of the ECJ that only it has jurisdiction to interpret EU law in relation to the EU and the Member States - a principle known as the "autonomy of EU law".1 2

Citizens' rights - UK courts will be able to ask for preliminary rulings from the ECJ on the interpretation of the citizens' rights section of the Withdrawal Agreement (Part Two), but only for a period of 8 years following the end of the transition period (Article 158). For questions related to the application for UK settled status, that 8 year period will start running on 30 March 2019.

Pending cases/preliminary rulings in the transition period - The ECJ retains the right after the transition period to:

decide on pending cases brought by or against the United Kingdom before the end of the transition period; and

give preliminary rulings on requests from UK courts made before the end of the transition period (Article 86).

Commission infringement cases after the transition period - The ECJ retains the right to hear cases brought by the Commission against the UK linked to breaches of EU law or part four of the agreement (i.e. the transition) which occurred before the end of the transition period. However, the Commission's right to bring these cases to the ECJ ends 4 years from the end of the transition period (Article 87).3 The four year cut-off reflects the fact that preparing for infringement cases can be time-consuming and may not be complete until after the transition period has ended.

ECJ case law - The Withdrawal Agreement also provides a continuing role for current and future ECJ case law. Provisions in the Withdrawal Agreement relating to EU law have to be interpreted in line with ECJ case law handed down before the end of the transition (Articles 4(3)). When interpreting the Withdrawal Agreement after the transition, UK courts are also required to have "due regard" to ECJ case law handed down after the end of the transition period (Article 4(4)).

Northern Ireland - The ECJ will retain jurisdiction over the areas of EU law which will apply if the Northern Irish "backstop" is activated (Article 14 of the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland). The provisions of the Protocol referring to EU law also have to be interpreted in line with ECJ case law (Article 15(3) of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland).2

The Transition Period

Part 4 of the Agreement provides for a transition or implementation period to begin as soon as the UK leaves the EU on 29 March 2019. The terms of the transition period were agreed in March 2017 and effectively mean the UK will continue to operate as if it were an EU Member State, though without participating in the EU's decision making processes. According to the UK Government's explainer for the Agreement:

The Withdrawal Agreement provides that during this period the UK will no longer be a member of the EU, but will be treated as such under Union law unless otherwise specified. This means that during this time EU law and EU supervision and enforcement arrangements will continue to apply to the UK. At the end of the implementation period, the current application of common rules will come to an end, as will the existing arrangements under which EU law applies in the UK.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

Fisheries during the transition period

Background

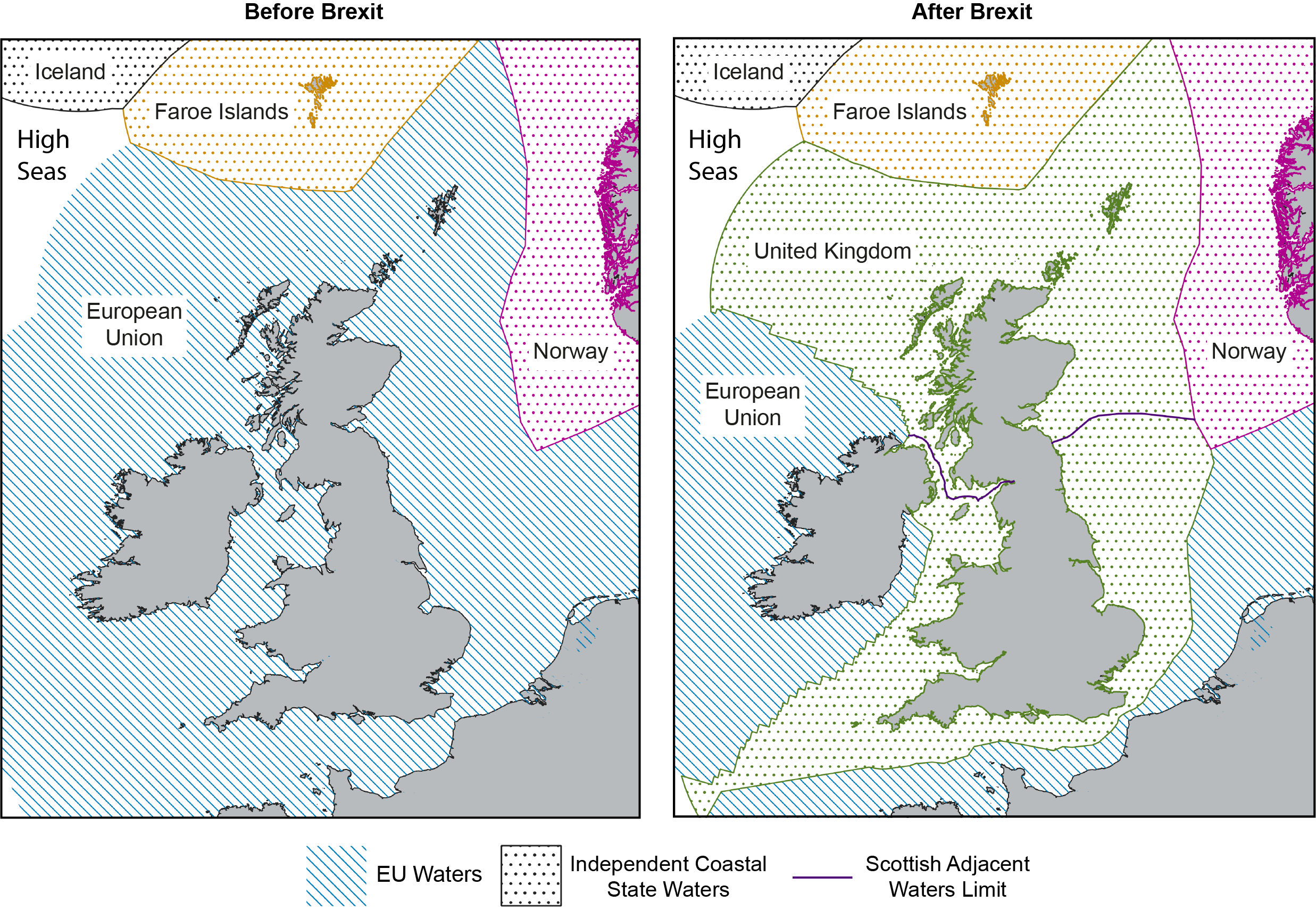

Analysis carried out by Napier (2017) provides background to the debate over the fishing element of the Withdrawal Agreement. Over the five year period from 2011 to 2015:

Less than half of the fish and shellfish landed from the UK Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) by EU fishing boats (43% by weight) was caught by UK boats

If landings by non-EU (Faroese and Norwegian) fishing boats are included, UK boats’ share of the total landings from the UK EEZ falls to less than one-third of the total (32% by weight)

Non-UK European Union fishing boats landed about 700,000 tonnes of fish and shellfish, worth almost £530 million, from the UK EEZ each year on average

UK fishing boats landed 92,000 tonnes of fish and shellfish, worth about £110 million, from other areas of the EU EEZ each year on average

Non-UK EU fishing boats therefore landed almost eight times more fish and shellfish (by weight) from the UK EEZ than UK boats did from other areas of the EU EEZ, or almost five times more by value

Whilst in the EU, UK (and so, Scottish) sea fisheries are governed by the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). Under the CFP, EU vessels have equal access to the EU waters. EU waters comprise Member States’ combined sea out to 200 nautical miles. Therefore, non-UK EU vessels can fish in the UK exclusive economic zone (EEZ) as long as they have quota, and vice versa.

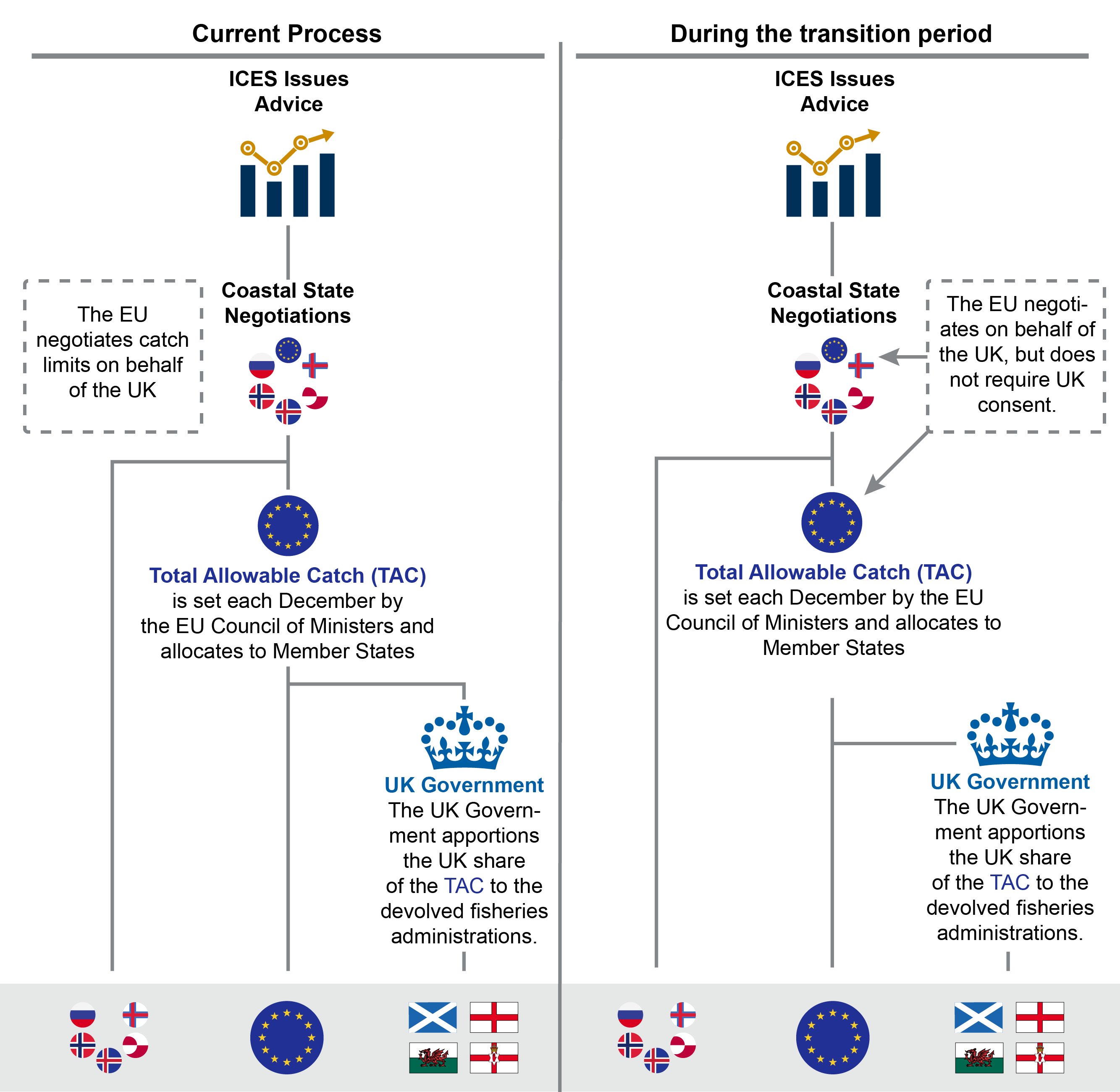

Fisheries during the transition period

During the transition period, the EU will determine, for UK waters (out to 200nm) -

who can fish, and

how much fish can be taken.

The UK will be consulted, but there is no obligation on the EU to obtain the UK's consent.

This is a consequence of Article 130 of the Withdrawal Agreement, which states -

As regards the fixing of fishing opportunities within the meaning of Article 43(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) for any period falling within the transition period, the United Kingdom shall be consulted in respect of the fishing opportunities related to the United Kingdom, including in the context of the preparation of relevant international consultations and negotiations.

So, the UK will be consulted during -

the coastal state negotiations where the EU and independent coastal states, such as Norway and the Faroe Islands, agree quota exchanges, and

the December Council of Ministers negotiations where quota is agreed under the common fisheries policy.

Article 130 also states that:

the relative stability keys for the allocation of fishing opportunities… shall be maintained.

This means that the share of quota allocated to the UK, and the EU member states will remain roughly the same during the transition period.

There is no information in the Withdrawal Agreement on whether this would remain for fisheries should the transition period be extended.

Agriculture during the transition period

Background

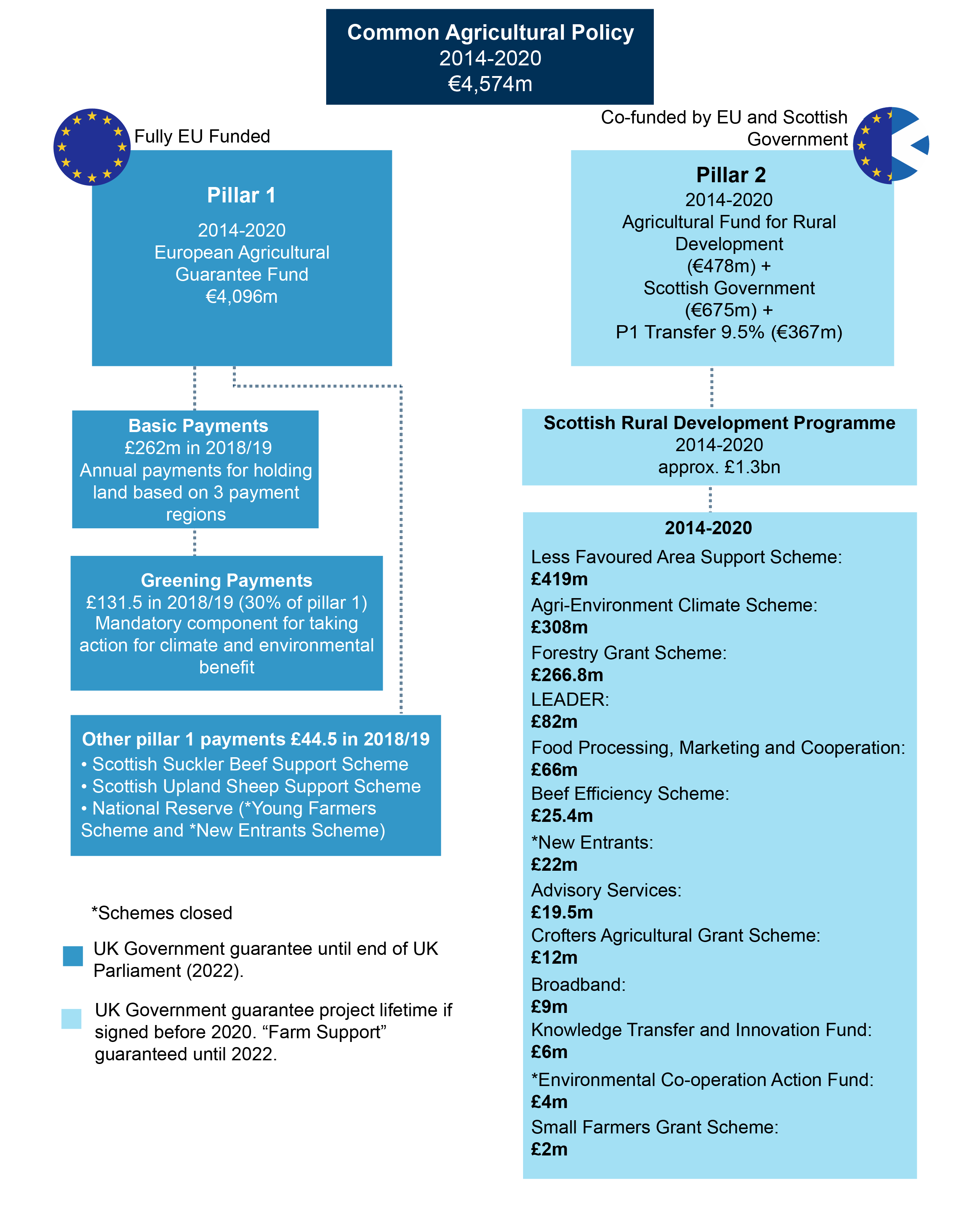

Whilst in the EU, Scotland is part of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The figure below shows how the CAP has been implemented in Scotland in the 2014-2020 period.

Currently, Scottish farmers have to comply with EU legislation and regulations including EU sanitary, phytosanitary (measures to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants) and veterinary standards. Agricultural products have tariff free access to the European Single Market. Compliance with these EU regulations also means that it is simpler to export to non-EU countries.

Once the UK leaves the EU, it will leave the CAP.

Agricultural support during the transition period

In June 2018 the Scottish Government stated:1

Between 29 March 2019 and 31 December 2020 we expect to continue to be bound by CAP rules, with the exception of the Direct Payments regulation which is expected to end in 2019 ... and some rules might continue for a period afterwards in particular those that underpin Pillar 2 payments.

The publication of the Withdrawal Agreement confirms this.

Article 137 states:

the Union programmes and activities committed under the multi-annual financial framework for the years 2014-2020 ... shall be implemented in 2019 and 2020 with regard to the United Kingdom on the basis of the applicable Union law.

But that:

Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 [on direct payments] ... shall not apply in the United Kingdom for claim year 2020.

Agricultural support during any extension to the transition period

According to the UK explainer to the Withdrawal Agreement, if the transition period is extended:

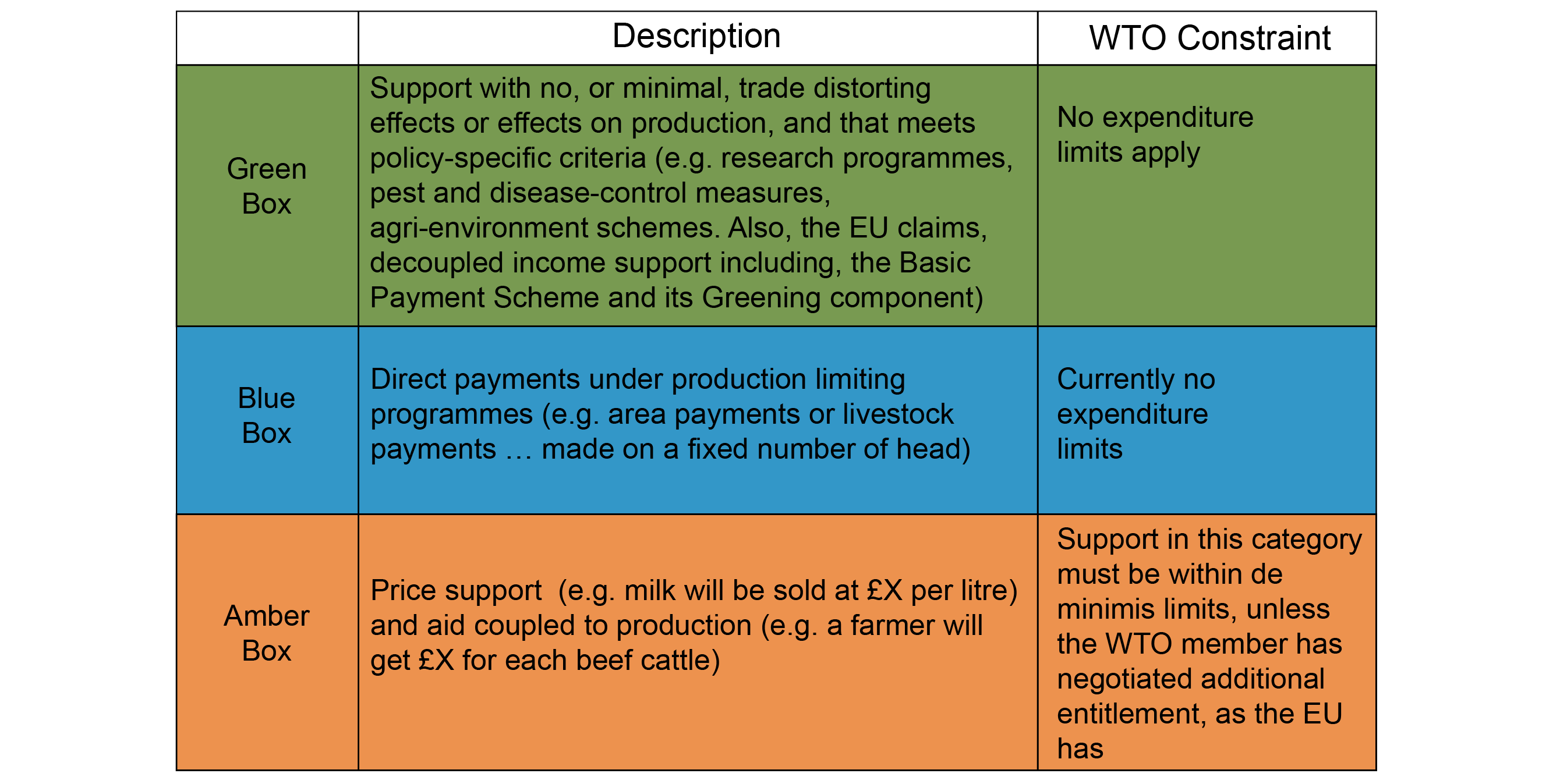

the UK would not be part of the CAP during the extension, and the UK would be free to introduce a new agricultural policy providing the payments remain within certain agreed limits [related to the World Trade Organisation Agreement on Agriculture].

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

Any UK farm support during an extended transition period must -

not be higher than CAP support levels in the UK in 2019, and

a minimum proportion of this support must be within ‘green box’ definitions under WTO Agreement on Agriculture. This minimum proportion will be determined by the Joint Committee.

These World Trade Organisation (WTO) "boxes" are shown below. The flip side of point two above is that the Joint Committee will determine the amount of non "green box" support that the UK may provide. That this is to be negotiated, means that proportions may change from the current position - perhaps to fit in with future agricultural policy in England and the devolved administrations. This is relevant to Scottish farmers, since the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme and the Scottish Upland Sheep Support Scheme are considered blue box support. It seems possible that negotiations on the proportions of support the UK will be allowed to provide in each of the boxes, could constrain the type and quantity of support that Scotland may make to its farmers during this period.

A Joint Statement by the UK farming unions states:

The draft Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, while not perfect, will ensure that there are no hard barriers on the day we leave the European Union, and will allow trade in agricultural goods and UK food & drink to continue throughout the transition period largely as before. This opportunity needs to be taken.

National Farming Union Scotland. (2018, November 20). UK Unions Comment on Draft Brexit Withdrawal Agreement and the Outline Political Declaration. Retrieved from https://www.nfus.org.uk/news/news/uk-unions-comment-on-draft-brexit-withdrawal-agreement-and-the-outline-political-declaration [accessed 23 November 2018]

Bilateral trade negotiations

During the transition period the United Kingdom may negotiate, sign and ratify international agreements entered into in its own capacity. These agreements cannot enter into force or apply during the transition period, unless the EU agrees to this.

Whilst this means the UK can begin to negotiate, agree and sign trade and investment agreements during the transition period, these will not be able to come into force until 1 January 2021 at the earliest.

The EU has committed in the Agreement to write to all those countries it currently holds a trading agreement with, to ask that the UK continues to benefit from that trade agreement during the transition phase. This will still require the relevant third country's agreement.

In the event the transition period is extended it is possible any future trade agreements will not be able to come into effect until even later. In addition, should the backstop contained in the protocol on Northern Ireland come into force at the end of the transition period leading to the UK entering into a customs arrangement with the EU, this may also limit the UK Government's ability to negotiate new trade agreements with other countries as the UK will continue to align the tariffs and rules applicable to its customs territory to the EU's external tariffs and rules of origin.

Extension of the transition period

Article 132(1) of the Agreement provides provision for the Joint Committee to agree an extension of the transition period up to for up to one or two years.

Whilst the transition period can be extended, Article 132(2) states that the UK shall be considered a third country for the purposes of participation in EU funding programmes and activities under the multi annual financial framework which will begin in 2021. A decision on the UK's future participation in EU funding programmes will be taken by the UK Government at a later stage.

During any extension, the UK will not participate in the collection of the EU's own resources (the EU budget) after the end of 2020. Instead, the UK would make contributions to the EU as set out in the UK Government's guidance to the Agreement:

The UK would make an appropriate financial contribution for the duration of the extension, reflecting its status in transition. The UK-EU Joint Committee would agree the amount and a schedule for making payments as part of the decision on extension, and the Government is committed to ensuring that this would represent a fair deal for UK taxpayers.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

Protection of EU Citizens' Rights

The EU treaties and EU legislation give all EU citizens (i.e. those who hold the nationality of an EU Member State) the right to move and reside freely in other Member States.

This right is unconditional in the first three months, other than the need to hold a valid identity card or passport. After three months, the right to remain only applies to workers, the self-employed, job-seekers, self-sufficient persons, student and certain family members. After three months, Member States can apply certain limited conditions to the right of residence, depending on the status of the EU citizen.

EU citizens who reside legally in another Member State for a continuous period of five years automatically acquire the right to permanent residence. This gives them enhanced protection against expulsion from the host Member State.

For further details on how the current system works see the August 2017 SPICe Briefing on Citizens' Rights and the Withdrawal Agreement.

One of the big questions is what impact Brexit will have on this system, given that the EU rules on free movement will no longer apply to the UK. In other words, once Brexit has happened, what rights will EU citizens living in the UK have, and what rights will UK citizens living in EU Member States have?

The provisions on citizens' rights in the Withdrawal Agreement appear to follow those agreed on in draft in March 2018. The main points to note are as follows:

General scope - The rules in the Withdrawal agreement only apply to those EU citizens who are lawfully resident in the UK under current EU rules (i.e. workers, self-employed, students etc.)

Permanent residents - The Withdrawal Agreement grants permanent residents the right to stay where they are living without any limitation in time. As a result, UK permanent residents in EU Member States retain the permanent right to remain in the Member State in question. Similarly, EU citizens who are permanently resident in the UK retain the right to remain permanently in the UK.

Non-permanent residents - The Withdrawal Agreement gives those who do not yet have permanent residence rights the right to stay until they have reached the five year threshold, at which point they will have the right to reside permanently.

Those arriving in the transition period - The protections in the Withdrawal Agreement apply in an equivalent way to EU citizens and UK nationals arriving in the host state during the transition period. The persons concerned will no longer be beneficiaries of the Withdrawal Agreement if they are absent from their host state for more than five years.

Family members - The Withdrawal Agreement also protects family members. Family members that are granted rights under EU law (current spouses and registered partners, parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren and a person in an existing durable relationship), who do not yet live in the same host state as the EU citizen or the UK national, are given the right to join them in the future.

Children - The Withdrawal Agreement also provides equivalent protection for children of EU citizens or UK nationals, whether born before or after the UK's withdrawal, or inside or outside the host state where the EU citizen or the UK national resided. There is, however, an exception for children born after the UK's withdrawal where a parent not covered by the Withdrawal Agreement has sole custody under UK/Member State family law.

Equal treatment - The Withdrawal Agreement lays down that EU citizens and UK nationals, as well as their respective family members, have the right to not be discriminated against due to nationality, and have the right to equal treatment with host state nationals

Loss of right of permanent residence - The right to permanent residence in the host country can be lost:

if the EU or UK citizen is absent from the country for a continuous period of 5 years

under the EU rules in Directive 2004/38/EC (public policy, public security - i.e. criminalityi - or public health) where the right was exercised before the transition period

under national immigration rules (e.g. UK immigration law) where the conduct in question happened after the transition period

where there has been abuse of those rights or fraud, as set out in article 35 of Directive 2004/38/EC

Application procedure - The Withdrawal Agreement allows states to choose whether or not to require parties to apply for the rights in the agreement, but lays down conditions for national procedures (e.g. as regards costs, time-frames, deadlines etc). The broad aim is to reduce unnecessary administrative burdens. The UK intends to set up an application procedure which will allow those with five years’ continuous residence to be granted "settled status". Those with less than five years’ continuous residence will be granted pre-settled status and will be able to apply for settled status once they reach the five-year point.1

Although the Withdrawal Agreement has specific sections on frontier workers and the recognition of professional qualifications, it doesn't grant UK citizens a more general right to move to other Member States similar to existing rights of free movement. In simple terms, the rights of permanent residence granted by the Withdrawal Agreement stop at the Member State borders.

The UK Government has previously argued that the Withdrawal Agreement should grant a more general right to onward freedom of movement for UK citizens in the EU. It seems that the UK Government now wishes to deal with this issue as part of the future relationship with the EU. In its explainer on the Withdrawal Agreement the UK Government states that:

As part of the future relationship with the EU, the UK will also seek to secure onward movement opportunities for UK nationals in the EU who are covered by the citizens’ rights agreement. Some of these UK nationals have chosen to make their lives in the EU, and this should be respected in the opportunities available to them if they decide to change their Member State of residence

The above is only a brief overview and doesn't cover the full scope of the agreement. Further details can be found in the European Commission's factsheet on the Withdrawal Agreement and in the UK Government's explainer on the Withdrawal Agreement.

Separation Provisions

The Withdrawal Agreement also provides procedures for ensuring that processes which are ongoing as the transition period ends will be able to be concluded. This section looks at the separation provisions outlined in relation to ongoing police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, ongoing judicial cooperation in civil and commercial matters and ongoing public procurement exercises.

Ongoing Police and Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters

Part 3 Title V (Ongoing Police and Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters) of the Withdrawal Agreement sets out the processes for dealing with police and judicial cooperation which begins during the transition period but has not concluded when the transition period ends.

The European Commission fact sheet Brexit Negotiations: What is in the Withdrawal Agreement notes that agreement provides for the “winding down of ongoing police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters”. More generally, it states that the agreement:

provides that the UK shall be disconnected at the end of the transition period from all EU databases and networks, unless specifically provided otherwise.

European Commission. (2018, November 14). Brexit Negotiations: What is in the Withdrawal Agreement. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-6422_en.htm [accessed 18 November 2018]

In relation to the UK's participation in justice and home affairs matters during the transition period, the fact sheet notes that:

All elements of the Justice and Home Affairs policy will continue to apply to the United Kingdom during the transition period, and the UK will remain bound by EU acts applicable to it upon its withdrawal. It may choose to exercise its right to opt-in/opt-out with regard to measures amending, replacing or building upon those acts.

However, during the transition period the UK will not have the right to opt-in to completely new measures. The EU may nevertheless invite the UK to cooperate in relation to such new measures, under the conditions set out for cooperation with third countries.

European Commission. (2018, November 14). Brexit Negotiations: What is in the Withdrawal Agreement. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-6422_en.htm [accessed 18 November 2018]

The fact sheet also outlines what might be described as transitional arrangements for police and judicial proceedings spanning the end of the transition period (i.e. those which have been started but not completed during the transition period). It states that any such proceedings should still be completed according to the same EU rules.

As a result of the Agreement, a criminal arrested by the UK on the basis of the European Arrest Warrant issued before the end of the transition period should be surrendered to the Member State that was searching for this person.

Similarly in the case of an authority from an EU Member State receiving a UK request to confiscate proceeds of crime before the end of the transition period, this should be executed according to the applicable EU rules.

Ongoing Judicial Cooperation in Civil and Commercial Matters

Part 3 Title VI of the Agreement provides rules for the continuation of cooperation on cross-border civil and commercial proceedings underway at the end of the transition period. In particular it lays down that the EU law on the recognition and enforcement of judgments will continue to apply to judgments handed down before the end of the transition period. The aim here is to ensure that there is certainty within the transition period as to which Member State court has the right to hear a dispute (thus reducing the risk of a case being dealt with by multiple courts). Similar rules exist for other areas of cross border civil law cooperation (for example in relation to rules on applicable law in contractual obligations and family law).

Public Procurement

Part 3 Title VIII of the Agreement addresses Ongoing Public Procurement and Similar Procedures. It addresses how ongoing public procurement processes at the end of the transition period will be finalised.

Public procurement – the current rules

Public procurement policy across the UK is currently governed by EU rules. The EU rules govern how works, goods and services are procured. The EU’s Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union sets out four key fundamental principles that underpin the public procurement regime across the EU—

Equal treatment: everyone must be treated equally and given an equal chance of winning a contract, and the procurement processes must be fair.

Non-discrimination: public bodies must not discriminate between individuals or businesses on the basis of the EU Member State in which they are located.

Transparency: public bodies must ensure that their procurement and contracting processes are clear and transparent, and contract opportunities should generally be advertised.

Proportionality: public bodies have a duty not to include contract requirements and terms that are disproportionate to the size or value of the contract.

As long as there is a certain EU cross-border interest in the subject of the procurement, public sector bodies are obliged to consider these principles throughout their procurements, at whatever value, regardless of whether the full EU procurement rules apply.

The procurement policy landscape in Scotland is based on the “Scottish Model of Procurement”, which is focussed `on “the best balance of cost, quality and sustainability”. A range of legislation and guidance underpins the approach to public procurement in Scotland:

The Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 and associated regulations and guidance sets out a range of principles and duties on contracting authorities, as well as governing the regime for certain contracts above below EU Thresholds.

The Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2015 transpose the EU Public Contracts Directive into Scots Law, and govern the regime for all public contracts above the EU thresholds.

According to the UK Government's explainer for the Agreement:

EU procurement rules, which are currently implemented in UK regulations, will continue to apply to public procurement and similar procedures which are ongoing at the end of the implementation period. These rules cover the procedures for the award of public contracts for works, services and supplies, utilities contracts, concessions contracts and non-exempted defence and security contracts above the relevant EU financial threshold values.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

The Agreement also contains a commitment by the UK and the EU to continue applying the non-discrimination principle, which prohibits discrimination against suppliers on the grounds of nationality when awarding public contracts which are subject to the ongoing procedures as described in the Withdrawal Agreement.

The UK Government has also committed to ensuring that procuring authorities will continue to use the EU’s online certification database (e-Certis) for up to nine months after the end of the transition period for ongoing procurement procedures.

Geographical Indications

Article 54(2), of Part 3 Title IV of the Agreement, covers geographical indications (GIs).

GIs are a distinctive sign used to identify a product as originating in the territory of a particular country, region or locality where its quality, reputation or other characteristic is linked to its geographical origin.

The EU has perhaps the most developed approach to GIs in the world in contrast to countries such as the United States which operates a system based on trademarks rather than GIs.

As an EU member state, the UK participates in the EU's approach to GIs and operates the EU Protected Food Names Scheme in the UK which has 86 protected food names including 14 Scottish products. Scotch Whisky also has an EU registered GI.

The Withdrawal Agreement sets out arrangements which mean existing UK GIs will continue to be protected by the current EU system until the future economic relationship is negotiated and comes into effect, meaning the current arrangements would then be superseded.

In the same way, EU GIs will remain protected in the UK until the future economic relationship is negotiated.

For more information on GIs see the SPICe Briefing, Geographical Indications and Brexit.1

The Ireland and Northern Ireland border

As referenced earlier in the briefing, the Irish border question occupied most of the attention during the negotiations with both the EU and the UK Government determined to avoid the imposition of a "hard border" on the island of Ireland after the transition period ends.

The current situation on the Irish border

Whilst both the United Kingdom and Ireland are Member States of the European Union there is no trading border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. This is because EU membership includes membership of the Single Market for goods, services, people and capital and also of the Customs Union.

Single Market membership means that in addition to providing tariff free access to EU markets, a common framework of regulations means companies in countries such as the UK, France, Italy or Poland have to abide by common standards - whether they trade across the EU or not. Compliance with common rules obviates the need for conformity checks at the border.

In addition, as a result of Customs Union membership, both the UK and Ireland operate the common customs tariff which applies to the import of goods into the European Union.

The development of the Irish backstop

The Prime Minister indicated in her 2017 Lancaster House speech that the UK intended to leave the Single Market and the Customs Union when it leaves the EU.1 This was reiterated in the subsequent White Paper: The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union.

This approach would mean the UK would no longer be bound to abide by the EU's common standards or apply the Common Customs Tariff to foreign goods. In this event, both customs and regulatory checks would be required on goods entering the European Union from the UK (including from Northern Ireland to Ireland).

Throughout the negotiations both the EU and the UK sought to ensure that when the UK leaves the EU, trade across the Ireland and Northern Ireland border will continue to operate as freely as it currently does, in line with the principles of the Good Friday Agreement, without any physical infrastructure at the Irish land border.

The UK Government initially suggested this should be addressed as part of the future trading relationship, whilst the EU insisted on the inclusion of a backstop in the Withdrawal Agreement which would keep Northern Ireland in the Customs Union and require it to observe appropriate EU standards to ensure frictionless north-south integration on the island of Ireland. The backstop would come into operation in the event the future relationship or other measures are not sufficient to ensure the continuation of frictionless trade.

Keeping Northern Ireland in the Customs Union and observing Single Market standards would have created a border in the Irish sea between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This approach was unacceptable to elements of the Conservative Party and the Democratic Unionist Party which provides a confidence and supply agreement for the UK Government. As a result, the UK Government opposed the EU's approach the backstop.

Another element of the backstop which caused disagreement between the EU and the UK related to whether the backstop would be a temporary or permanent arrangement. The EU insisted the backstop had to be permanently available in case the future EU-UK relationship did not solve the border question, whilst members of the UK Government often suggested any backstop should only be temporary.

A detailed background on the development of the backstop was published by RTE's Europe Editor, Tony Connelly on 20 October 2018.

The Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland

As the negotiations continued throughout 2018 and no obvious solution to meet the red lines of both the EU and the UK emerged, the option of a temporary customs relationship for the whole of the UK (rather than just Northern Ireland) was proposed by the UK Government. Whilst the EU had initially suggested that the customs relationship on offer was for Northern Ireland only, the idea of a customs relationship with the whole of the UK would help solve the customs element of the Irish border question.

As a result, the backstop proposal was amended to include the UK as a whole in a customs relationship with the EU. In the Withdrawal Agreement, the Northern Ireland and Ireland Protocol addresses the proposal for an EU-UK wide customs arrangement. The Protocol sets out the arrangements for ensuring the avoidance of a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland as a result of Brexit. These include provision for N0rthern Ireland to continue to abide by the EU's Customs Code and relevant Single Market in goods legislation to ensure free movement of goods across the Ireland and Northern Ireland border.

According to the European Commission's Fact Sheet on the Protocol:

The Protocol includes all the provisions on how the so-called "backstop" solution for avoiding a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland would work. This forms part of the overall Withdrawal Agreement and will apply unless and until it is superseded, in whole or in part, by any subsequent agreement. Both the EU and the UK will use their best endeavours to conclude and ratify a subsequent agreement by 1 July 2020.

As part of the Protocol, a single EU-UK customs territory is established from the end of the transition period until the future relationship becomes applicable. Northern Ireland will therefore remain part of the same customs territory as the rest of the UK with no tariffs, quotas, or checks on rules of origin between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

European Commission. (2018, November 14). Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-6423_en.htm [accessed 14 November 2018]

The Protocol makes clear that the backstop is "not the preferred or expected outcome" with the UK Government suggesting it still hopes to negotiate a future relationship which means the backstop is never required. Linked to this aspiration is the ability to extend the transition period if necessary and desirable rather than invoke the backstop.2

Article 1 of the Protocol also makes clear that the backstop arrangement should not be seen as creating a permanent relationship between the UK and the EU and that it is only intended to apply temporarily (if at all) unless and until it is superseded.

Given a permanent solution to preventing a hard border on the island of Ireland has not yet been found, this temporary solution may however become permanent by default in the sense it can never be superseded unless new technology addresses the issue or the UK or the EU's red lines change.

The permanence of such a solution to the Irish border question was also addressed in the Protocol with Article 20 containing a review clause for the Protocol:

Article 20 of the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland

If at any time after the end of the transition period the Union or the United Kingdom considers that this Protocol is, in whole or in part, no longer necessary to achieve the objectives set out in Article 1(3) and should cease to apply, in whole or in part, it may notify the other party, setting out its reasons. Within 6 months of such a notification, the Joint Committee shall meet at ministerial level to consider the notification, having regard to all of the objectives specified in Article 1. The Joint Committee may seek an opinion from institutions created by the 1998 Agreement.

If, following the consideration referred to above, and acting in full respect of Article 5 of the Withdrawal Agreement, the Union and the United Kingdom decide jointly within the Joint Committee that the Protocol, in whole or in part, is no longer necessary to achieve its objectives, the Protocol shall cease to apply, in whole or in part. In such a case the Joint Committee shall address recommendations to the Union and to the United Kingdom on the necessary measures, taking into account the obligations of the parties to the 1998 Agreement.

Protecting the Good Friday Agreement and the Common Travel Area

Articles 4 and 5 of the Protocol address matters in relation to the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and the Common Travel Area.

Article 4 commits the UK Government to ensuring there is "no diminution of rights, safeguards and equality of opportunity" as set out in the Rights, Safeguards and Equality of Opportunity chapter of the GFA. According to the UK Government:

This means that the UK will take steps to ensure that the rights and equalities protections in that chapter, and currently available to individuals in Northern Ireland, are not diminished as a result of UK Exit.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

The six EU laws which will be covered by this commitment are:

Council Directive 2004/113/EC of 13 December 2004 implementing the principle of equal treatment between men and women in the access to and supply of goods and services

Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation

Council Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June 2000 implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin

Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000 establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation

Directive 2010/41/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 July 2010 on the application of the principle of equal treatment between men and women engaged in an activity in a self-employed capacity and repealing Council Directive 86/613/EEC

Council Directive 79/7/EEC of 19 December 1978 on the progressive implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women in matters of social security

Article 5 ensures the UK and Irish Governments can continue to ensure the smooth operation of the Common Travel Area which pre-dates both countries membership of the European Union. This means that British and Irish citizens should be able to continue to live, work and study in the other state after Brexit.

Article 13 of the Protocol guarantees the UK Government's commitment to ensuring the continuation of North-South cooperation as set out in the GFA.

The EU-UK Customs Territory

As discussed earlier in the briefing, the Protocol includes provision for an EU-UK customs territory to form an element of the Northern Ireland backstop.

In the event the backstop is required, the establishment of a single customs territory would mean there would be no need for tariffs, quotas or checks on rules of origin in trade between the EU and the UK.

Articles 6 to 8 and Annexes 2 to 10 of the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland set out the arrangements for the customs territory. The rules as they relate to fisheries, agriculture and level playing field issues are discussed later in this section of the briefing.

Annex 2 of the Protocol sets out the rules underpinning the customs territory. These include in Article 3 a requirement on the UK to apply:

the Union's Common Customs Tariff

the Union's rules on the origin of goods

the Union's rules on the value of goods for customs purposes

Annex 2 Article 4 sets out that the UK is also committed to working with the EU to ensure continued alignment of its commitments on tariff-rate quotas and to the EU's trade defence regime.

Annex 2 Article 6 also prohibits the UK from applying "to its customs territory a customs tariff which is lower than the Common Customs Tariff for any good or import from any third country". The provisions set out in Article 6 of Annex 2 of the Protocol would, in effect prevent the UK conducting its own independent trade policy if or when the backstop is in force.

Whilst the Protocol and its annexes set out the broad terms of an EU-UK customs territory, more detail on its actual operation will be required. Article 6 of the Protocol states that:

The Joint Committee shall adopt before 1 July 2020 the detailed rules relating to trade in goods between the two parts of the single customs territory for the implementation of this paragraph. In the absence of such a decision adopted before 1 July 2020, Annex 3 shall apply.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756374/14_November_Draft_Agreement_on_the_Withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union.pdf [accessed 16 December 2018]

Annex 3 also sets out some further details outlining how a single EU-UK customs territory would work.

Whilst the EU-UK customs territory is established by Article 6 of the Protocol, Article 7 provides that nothing in the Protocol "shall prevent the United Kingdom from ensuring unfettered market access for goods moving from Northern Ireland to the rest of the United Kingdom's internal market". This commitment is required as a result of Northern Ireland's different relationship with the EU's Single Market compared to the rest of the UK.

Northern Ireland's access to the Single Market

Article 6 of the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland also makes arrangements for the free movement of goods between Ireland and Northern Ireland with regards to common standards. These provisions seek to ensure regulatory alignment to ensure that Northern Ireland businesses can place products on the EU Single Market without restriction, and vice-versa.

To ensure this approach, the Union's Customs Code and some EU law related to the free movement of goods will continue to apply to Northern Ireland.

The Union Customs Code

The Union Customs Code (UCC) defines the legal framework for customs rules and procedures in the EU customs territory. Within the EU Customs Union it is necessary to ensure all rules under the UCC are met before a good can be placed for free circulation on the EU's Single Market.

The EU legislation on goods standards applicable to Northern Ireland under the backstop is set out in Annexe 5, 6 and 8 to the Protocol. Running to around 80 pages of Directives and Regulations, these relate to:

legislation on VAT and excise in respect of goods

legislation on goods standards

sanitary rules for veterinary controls (phytosanitary rules)

rules on agricultural production and marketing

state aid rules

The EU rules applicable to Northern Ireland will form only a small part of the EU's overall rule book. According to the UK Government's explainer:

Only rules that are strictly necessary to avoid a hard border and protect North-South cooperation have been included in Annex 5. They constitute a small fraction of the single market rules that currently apply to the UK, representing a significant increase in the areas over which the UK Parliament or devolved institutions in Northern Ireland will be free to legislate.

UK Government. (2018, November 14). Explainer for the agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756376/14_November_Explainer_for_the_agreement_on_the_withdrawal_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Northern_Ireland_from_the_European_Union___1_.pdf [accessed 16 November 2018]

Northern Ireland's alignment to EU law in relation to the Single Market in goods along with the EU-UK customs territory ensures that there will be no need for checks and controls on goods crossing between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

This approach will however mean that there will need to be checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK. According to the European Commission:

In order to ensure that Northern Irish businesses can place products on the EU's Single Market without restriction – and given the island of Ireland's status as a single epidemiological area – there would be a need for checks on goods travelling from the rest of the UK to Northern Ireland. There would be a need for some compliance checks with EU standards, consistent with risk, to protect consumers, economic traders and businesses in the Single Market.

The EU and the UK have agreed to carry out these checks in the least intrusive way possible. The scale and frequency of the checks could be further reduced through future agreements between the EU and the UK.

European Commission. (2018, November 14). Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-6423_en.htm [accessed 14 November 2018]

For industrial goods, checks are based on risk assessment, and can mostly take place in the market or at traders' premises by the relevant authorities. Such checks will always be carried out by UK authorities.

As for agricultural products, already existing checks at ports and airports will need to continue, but will be increased in scale in order to protect the EU's Single Market, its consumers and animal health.

Article 15(5) of the Protocol also addresses an issue where the EU adopts a new act that falls within the scope of the Protocol, but doesn't amend or replace a piece of EU legislation listed in the Annexes to the Protocol. In the event this happens:

The Union shall inform the United Kingdom of this adoption in the Joint Committee. Upon request of the Union or the United Kingdom, the Joint Committee shall hold an exchange of views on the implications of the newly adopted act for the proper functioning of this Protocol within 6 weeks after the request.