Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill

This briefing provides information on a Private Bill to incorporate and reconstitute the Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission. The Pow of Inchaffray is a drainage channel, located near Crieff.

Executive Summary

The Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill1 is a private bill to incorporate and reconstitute the Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission.

Private Bills are different to other Bills in that they involve measures sought in the private interests of the promoter, and to which others may object.

In summary, the Bill:

establishes a Commission and sets out the Commission's powers and functions (sections 1 and 2; schedule 1);

provides procedures for the appointment of the Commissioners and their terms of office (sections 4 and 5; schedule 2);

identifies the land that is deemed to benefit from the drainage channel (‘the benefited land’) (section 3);

makes provision for meetings, including provision for decisions by a majority of Commissioners attending (sections 6, 7 and 9; schedule 3);

sets out how revenue will be collected, how much and from whom (sections 10-14 and schedule 4);

gives extensive powers to the Commission to access the benefited land (section 17)

provides an effective mechanism for the Commission to recover debts through the courts (section 21)

repeals the Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Act (1846) (section 26)

The owners of land or property within the benefited land are referred to as heritors in the Bill (section 27). This is how they are referred to in the remainder of this briefing.

Why is a Private Bill needed?

Private Bills are different to other Bills in that they involve measures sought in the private interests of the promoter, and to which others may object. The Scottish Parliament website explains the purpose of Private Bills in more detail:1

A Private Bill is introduced by a promoter, who may be a person, a company or a group of people, for the purpose of obtaining particular powers or benefits that are in addition to, or in conflict with, the general law. Private Bills generally relate to the property or status of the promoter. For example, the National Galleries of Scotland Bill granted powers to the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland to complete the Playfair Project which was a series of improvements undertaken by the National Gallery and the Royal Scottish Academy.

The Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill2 (referred to as the 'the Bill') and accompanying documents and maps are available on the Scottish Parliament website. The Bill was introduced by the Pow of Inchaffray Commissioners on 17 March 2017.

The land in question is currently covered by the Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Act 1846 ('the 1846 Act').3 It was previously covered by a 1696 Act of the Parliament of Scotland.

The 1846 Act gives the existing Commissioners the power to carry out works and improvements, and provides for costs of improvements and maintenance to be shared amongst owners of land said to be benefited by the Pow. The Promoters of the Bill give three main reasons why a private bill is now needed:

the construction of houses on the benefited land in recent years means there should be a new mechanism for sharing the costs (and for the home owners to be represented on the Commission)

the legislation should be modernised and simplified. (For example, much of the 1846 Act concerned the construction of the original improvement works, which have long since been completed).

no public bodies are prepared to take over the functions of the Commission.

History of the Pow

For a drainage ditch the Pow of Inchaffray has a long and colourful history. As local historian Norman Watson put it:1

The Pow is short in length. But its history stretches back into the Dark ages

The promoters of the bill set out some key milestones (Promoter's Memorandum, paras 9- 13):

"ancient times" – the area is thought to have been marsh land and impassable during winter months. A few patches of land rising above floodwater level formed ‘islands’, including one on which the Abbey of Inchaffray was built;

1200 AD – the drainage channel was originally dug by Augustinian canons;

1314 – further work was ordered by King Robert the Bruce. (Abbot Maurice of Inchaffray is said to be the man who led the celebration of mass for the Scottish troops before the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 and the further works were ordered by way of thanks);

1696 – responsibility for draining the Pow fell to the ‘great houses’ and the old Scottish parliament put responsibility for the channel on a statutory basis;

1846 – a new Act gave greater powers to the Commissioners and ensured costs would be shared amongst owners of land benefited from the works.

Why a drainage channel is needed

The Bill's Promoters state that1

The Commission's role in preventing the floods which had blighted the low lying land in Strathearn for centuries means that the land drained is among the most fertile agricultural acreage in Scotland. In addition, the Commission‘s work has made residential development possible in some areas such as the former Balgowan Sawmill Site. It is therefore vitally important that the Pow is maintained to prevent flooding in this area.

How the 'benefited land' is defined

Following the 1846 Act a survey was commissioned to identify the land which may be affected by (and benefit from) drainage into the Pow. The survey was intended to define the area of land where economic value was increased as a result of the works. The Promoters indicate that, on the basis of their detailed knowledge of the area, and the fact that the topography is largely unchanged, the 1846 survey remains accurate today.

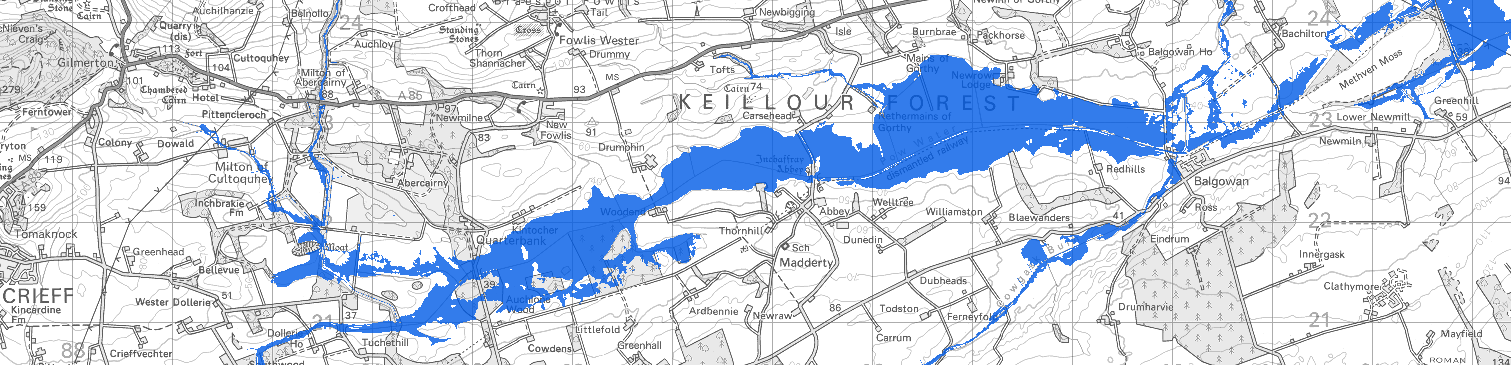

The map below is reproduced from the SEPA interactive flooding map, which indicates areas of Scotland at risk from flooding. It is possible to look at localised areas at risk of flooding in detail [here], and this may provide useful context.

Roles of public bodies

There are a number of public bodies with some responsibility for flooding and related issues, which includes the following1

The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) is Scotland’s national flood forecasting and flood warning authority. SEPA operates Floodline, which provides live flooding information and advice on how to prepare for, or cope with, the impacts of flooding. SEPA is also the strategic flood risk authority and has produced Flood Risk Management Strategies for parts of Scotland, working closely with other organisations responsible for managing flood risk.

local authorities are responsible for producing Scotland’s Local Flood Risk Management Plans and work in partnership with SEPA, Scottish Water and other responsible authorities to develop these. Local authorities are also responsible for implementing and maintaining flood protection measures, clearing and repairing watercourses to reduce flood risk and gully maintenance for local roads.

Scottish Water is responsible for the drainage of surface water from roofs and paved ground surfaces within a property boundary. Scottish Water can help to protect properties from flooding caused by overflowing or blocked sewers.

The Promoter's Memorandum explains that contact had been made with SEPA, with Scottish Water, and with the local authority (Perth and Kinross Council).2 In its response, quoted in the Memorandum, SEPA said:

As you may be aware in England and Wales the equivalent body to SEPA, the Environment Agency carries out certain works on rivers and watercourses. SEPA does not have the same remit as the EA and SEPA does not carry out the kinds of works referred to in your email. As such SEPA could not take over the works carried out by the commission

Scottish Parliament. (2017, March 17). Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill. Promoter's Memorandum (SP Bill 9-PM, Session 5), para 49. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/Pow%20of%20Inchaffray%20Drainage%20Commission%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill09PMS052017.pdf [accessed 18 May 2017]

Perth and Kinross Council said:

In this time of austerity and reducing budget/resources, PKC would not be willing to take on the administration/maintenance of the Inchaffray Pow. I would imagine Scottish Water would give the same response

Scottish Parliament. (2017, March 17). Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill. Promoter's Memorandum (SP Bill 9-PM, Session 5), para 48. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/Pow%20of%20Inchaffray%20Drainage%20Commission%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill09PMS052017.pdf

Scottish Water did not respond and, as the Promoter explained in the Memorandum, it took the view that Scottish Water has no intention or interest in taking on responsibility for the Pow.5

What the Bill will do

The Commission and the Commissioners

The legal status of the Commission

The Bill says the Commission is a body corporate (section 1(1)). This means it is a separate entity in law from the commissioners who are appointed to it.

As a result, the Commission can carry out a wide range of legal acts in its own name, such as enter into a contract or borrow money (schedule 2, para (2)).

Another important aspect of this is that, as long as they act in good faith, the Commissioners are protected from personal liability for anything done in the exercise of their functions as Commissioners (section 20).

The Commissioners - an overview

Under the Bill the Commission is to have seven Commissioners (section 2(1)).

For this purpose, the benefited land is divided into four sections. Two Commissioners are to serve each of the upper, middle and lower sections, and one Commissioner the Balgowan section (sections 2(2) and 3(4)). (The latter section covers the new housing estate adjacent to the Pow.)

Each Commissioner must either own land in the section to which they are appointed or be the representative of someone who does (section 8 and schedule 2, para 1).

On the other hand, schedule 2 (para 13) says a Commissioner may be dismissed when he or she ceases to be a heritor. This seems to give the Commission a discretion to allow a Commissioner to continue in those circumstances.

This difference of approach notwithstanding, the requirements relating to land ownership are intended as major safeguards for heritors. The aim is to ensure that Commissioners effectively represent heritors’ interests (Promoter’s Memorandum at para 23). In practice, from the heritors’ perspective, an important aspect of this is likely to be ensuring that charges on heritors are not unnecessarily increased (see the Promoter’s Memorandum at para 23).

Other potential safeguards are discussed at various points later in this briefing.

The Commissioners - appointment and dismissal

The Bill provides, that, at a meeting, each Commissioner can appointed by a majority of the heritors (owners) attending from the relevant section of the Pow (schedule 2, para 4).

A Commissioner will usually be appointed for ten years, with the possibility of unlimited reappointment. He or she can resign early.

The Commission “may” also terminate a Commissioner’s appointment early on various grounds (section 4 and schedule 2, paras 9, 11 and 13).

Related to the issue of termination, other parts of property law also deal with the situation where groups of owners benefit from a common asset. For example, a piece of amenity ground on a housing estate or the common parts of a block of flats. Furthermore, sometimes these parts are not managed or maintained by the owners directly. Alternatives include a property factor; a residents’ association or a land maintenance company.

If a group of owners do not like how the person or body appointed is performing, experience of these related types of arrangements suggest it is important that the owners can act together (by some means) to end the arrangement and make a new one. In the Bill, the chosen mechanism is the Commissioners acting together. The heritors themselves cannot decide on early termination, in contrast to their role in relation to appointment (section 4 and schedule 2, para 13).

The functions and powers of the Commission - an overview

The Bill defines the Commission’s functions in terms of what is “necessary or desirable” to maintain effective drainage of the benefited land (schedule 1, para 1(1)).

The specific functions of the Commission will include the ability to “repair, maintain and renew” the Pow and to carry out “improvements" and “protective works” to it (schedule 1, para (1)(a) and (c)).

The Commission will have a broad power to do anything which the Commission thinks is "necessary or expedient to carry out its functions" (schedule 1, para 2) as well as a range of specific powers.

The statutory language used in this part of the Bill (with particular reference to the highlighted words above) appears to confer significant statutory powers on the Commission. This is potentially significant because, although the Commissioners will be owners representing different sections of the Pow, in any group of owners there can be a wide range of different financial circumstances and priorities.

The approach in the Bill to improvements differs from at least one other statutory scheme associated with groups of owners. This is the Tenement Management Scheme ('TMS'), found in the Tenement (Scotland) Act 2004 ('the 2004 Act'). It relates to blocks of flats and applies to the extent the title deeds are silent on issues of common management and maintenance. It provides for majority rule.

Whilst the policy considerations associated with the two schemes are clearly not identical, it should be noted that the TMS excludes most “improvements” from its scope (TMS, rule 1.5). The policy aim was to offer owners some protection from more ambitious, potentially expensive projects which they did not vote for.1

Financial powers and obligations

Some of the Commission’s most significant powers will relate to the charging regime discussed in more detail later in this briefing.

Related to its financial powers, the Bill provides that the Commission must keep accounts and have them audited (schedule 1, paras 9-11). The Commission must use its resources economically, efficiently and effectively (schedule 1, para 10).

Right of access

The Commission will have a right of access over the benefited land (and land adjacent to the Pow) “for any purpose connected with its functions, rights or obligations” (section 17). The statutory language used here seems to confer a significant power.

There are some safeguards for heritors: Seven days' notice is required, except in emergencies. Access to buildings (as opposed to land) requires the consent of the owner or occupier. Compensation is payable for any resulting damage to land or buildings (section 17).

Debts

The Bill provides for the Commission to be able to recover debts due to it via civil proceedings in the local sheriff court (section 21). This includes sums due by heritors to the Commission.

Section 21 was necessary because the debt recovery mechanism utilised by the 1846 Act was abolished by an Act of the Scottish Parliament in 2002.2i

Meetings

The Bill provides that the Commission must hold two general business meetings per calendar year (schedule 3, para 1). A quorum is three Commissioners and decisions are taken by a majority of commissioners attending the meeting, with the chair having the casting vote (schedule 3, paras 1–5).

Whilst the 1846 Act makes no specific provision for meetings of heritors, the Bill provides that the Commission must call a heritors’ meeting in a range of circumstances (over and above the appointment of a Commissioner). For example, heritors’ meetings must be convened before each general business meeting of the Commission (section 7(1)(b)).

Three or more heritors can also ask for a heritors' meeting to alter the number of Commissioners; to alter the ditches included in the Pow or to change where the boundaries to the Pow's sections lie (sections 2(3); 3(2) & (3); 7(1) and 9). The Commission may also call a meeting for any other purpose at any other time (section 7(2)).

Resolutions

A resolution must be passed by the heritors to alter the ditches or change the boundaries to the sections. The heritors representing 75% of the sum of chargeable values of all the heritors' land can pass such a resolution (section 9).

The proposed charging regime

The principles said to underpin the scheme

The Commissioners considered a number of options to calculate the charges each of the heritors would be due (see the annex to Promoter's Memorandum). They suggested that any charging scheme should include the following principles:1

it should be fair to all heritors;

it should be transparent;

it should avoid unnecessary valuation costs;

the amount charged should relate to the value of the Pow works to each heritor; •

there should be flexibility to meet changing circumstances (e.g. construction of additional houses);

the scheme should be future proofed as much as possible (to maximise time before further legislation is required);

the risk of disputes should be minimised.

The basics of the charging scheme

The Bill proposes a charging scheme which relates the costs to the level of benefit each heritor is thought to gain. However, rather than calculate this for each individual heritor, the proposed approach is to make a calculation for specified categories of land use (residential, commercial, agricultural etc.).

The first stage in the process is for the Commission to estimate the total budget needed for the forthcoming financial year. The contribution each heritor is required to make to the budget is then based on the chargeable value of the land in question.

The chargeable value of a heritor’s land is an estimate of the difference between the current market value of that land use type (the assumed value) and the value of that land type had no drainage works been carried out (known as the base value and fixed at £500 an acre).

The assumed value

The assumed values for different types of land are initially fixed in schedule 4 of the Bill, based on a fixed rate per acre of each land use type.

Accordingly, for a residential property it is the size of the plot which is significant, not the size of the house. Indeed, the assumed value excludes works carried out by the heritor or predecessors, for example, building a house. The assumed value for land with planning consent for residential use, for example, is £300,000 per acre (compared to £50,000 for commercial use and a range of £2,500 - £6,000 for agricultural use).

Reviews

The base value and assumed values are to be reviewed by an independent assessor every ten years (section 11).

In addition, the Commission may appoint a surveyor “at any time” to amend the land categories in schedule 4, and with it make “consequential amendments” to the assumed value per acre for that category (section 12).

What the annual budget can include – overview

The annual Commission budget must allow for any anticipated surplus or shortfall from the previous assessment year. It may include provision for a reserve fund to cover extraordinary expenditure (section 10(2)).

‘Missing shares’

On any shortfall from previous years, one issue is what happens if one heritor cannot or will not pay his or her share in any given assessment year.

As discussed earlier in this briefing, court action by the Commission to recover the debt would be possible (section 21). Another approach would be to spread the costs from the ‘missing share(s)’ between the other heritors in the following assessment year (possible by virtue of section 10(2)(a)).

There are pros and cons to each approach. For example, a court action incurs legal costs (which presumably would be passed on to the heritors in the next assessment year). On the other hand, a failure to ever pursue court action against individuals for missing shares could lead to a situation where the compliant majority was regularly subsidising a reluctant minority (and that minority had no incentive to change its behaviour).

The promotion costs of the Bill

If the promotion costs associated with the Bill cannot be recovered from the heritors under assessments related to the 1846 Act, then the Bill says these costs can also be recovered from heritors under the Bill for the first three assessment years (section 10(10) and (11)).

The Parliament’s fee for this type of private bill is £2,000 and there are other potential parliamentary costs (e.g. relating to any visits; any witness expenses etc.). The promoter will also incur legal costs associated with the Bill.

Paying the bill by instalments

There is no option in the Bill for heritors to pay their annual charge in instalments, in contrast, to, for example, council tax charges.

Resolving disputes

In practice, a heritor may be unhappy about the proposed level of the Commission budget (reflected in his or her annual bill) in any given year. However, as noted by the Scottish Government in its written submission (at para 8), the Bill does not provide a mechanism for a dispute to be resolved by a third party (e.g. by way of an appeal mechanism set out in statute).

For disagreements about a proposed amendment to the land categories (and associated land values), heritors can make “representations” to the surveyor on this topic. The surveyor “must have regard to” these (section 12(3) and (4)). However, as noted by the Scottish Government in its written submission (at para 14), there is no further opportunity for challenge. This can be compared to the 1846 Act, where the local sheriff court appears in several places as the dispute resolution mechanism of last resort.

Aside from the sheriff court, there are a number of out of court dispute resolution mechanisms which could have explicitly featured in the Bill. For example, resolution by an adjudicator appears in the legislation associated with disputes between private landlords and tenants about tenancy deposits. Adjudicators are also regularly used in the construction industry as a quick (and relatively cheap) dispute resolution mechanism.

Judicial review is the court procedure which can be used in circumstances including where a statutory body does something which it is not authorised to do under statute. To be available, the procedure does not need to be explicitly referred to in the statute associated with the body in question, hence it could apply to the Commission. However, judicial review is an expensive procedure, only being available at the Court of Session in Edinburgh (as opposed to in the local sheriff court.)

Issues for prospective purchasers

The ideal situation is that prospective purchasers of land or property forming part of the benefited land would have advance notice of the potential charges as a result of the Bill before committing to a purchase. Indeed, obtaining advance notice of any financial obligations associated with land or property prior to purchase is an important aim of any conveyancing transaction.

In this regard, note that a local solicitor might not be used by a prospective purchaser in relation to land or property within the benefited land of the Pow, therefore no local knowledge can be assumed by the solicitor carrying out this role.

Methods used by solicitors

Solicitors acting for prospective purchasers try to obtain advance notice of financial obligations by a variety of methods. No method is without its drawbacks or limitations, which is why solicitors typically use a range of methods to strengthen the rigour of the overall investigation.

In the first place, there is the Home Report which accompanies the marketing of homes for sale in Scotland.1 In its Property Questionnaire, sellers provide responses to a series of questions about their property, which might highlight the Pow charges. However, a written submission on the Bill from the Scottish Government2 (at para 19) and a further submission from Professor Rennie (a property law academic)3 (at para 2) suggest possible limitations to this method of discovery for the Pow.

Another mechanism is the Property Enquiry Certificate, normally requested by solicitors in the course of a conveyancing transaction. This provides information on a variety of topics, including whether the drainage is public or private. Details of private arrangements could then (in theory) be probed further by the solicitor acting for the prospective purchaser. However, Professor Rennie (written submission, para 3) suggests that, at present, the Certificate itself would not highlight a specific statutory scheme of limited geographical scope.

A key feature of our conveyancing system is that land or property is registered or recorded in one of the two publicly searchable property registers in Scotland - the Land Register or the Registers of Sasines (both maintained by the Registers of Scotland). These registers are routinely searched by solicitors as part of a conveyancing transaction. However, unless the charges associated with drainage are contained in title conditions affecting the land or property in question, they probably would not be highlighted by this method. (The Scottish Government also offers this view at paras 16-18 of its written submission).

The approach in the Bill

The Bill provides that the Commission must maintain a Register of Heritors with the names and addresses of heritors, which, with some qualifications, it is intended is kept up to date (section 16). However, as Professor Gretton (a property law academic) notes in his written submission,4 it is searchable by heritors (section 16(4)) but not by members of the public. Professor Gretton suggests that this is "a departure from usual legislative practice".

In a similar vein, as Professor Gretton notes in his written submission, the land plans associated with the Pow, revealing the benefited land, can be inspected by heritors (section 15(1)). However, there is no provision in the Bill for them to be searchable by the public.

The land plans are currently available on the Parliament's website on the webpage associated with the Bill and the Promoter's Statement5 (para 15) says they can also be publicly inspected at a solicitor's office. However, knowledge of the new legislative scheme (of limited geographical scope) would be required to benefit from these sources. In addition, note that, under the Bill, the land plans can be subsequently amended to alter the boundaries of the benefited land and the ditches (section 3).