Rural Affairs and Islands Committee

Follow-up inquiry into salmon farming in Scotland

Section 1 - introduction

Background to the inquiry

The Session 5 Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) Committee undertook a wide-ranging inquiry into salmon farming between January and May 2018. The Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform (ECCLR) Committee considered the impact of salmon farming on the marine environment in advance of the REC Committee’s wider inquiry and its findings fed into the REC Committee inquiry. To inform both committees’ consideration, a review of research on aquaculture and the environment was commissioned from the Scottish Association for Marine Science Research Services Limited.

The REC Committee's report, 'Salmon farming in Scotland', was published in November 2018. For convenience, the report's 65 conclusions and recommendations are set out in Annexe A of this report.

The Scottish Government responded to the REC Committee report in January 2019, telling the Committee that it agreed with many of its conclusions and “view[ed] the report as a helpful staging point in the development of the sector in Scotland”. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) responded to the REC Committee report in November 2018.

In the REC Committee's legacy report at the end of Session 5, it expressed disappointment by what it saw as a lack of progress in implementing the report's recommendations. It suggested, therefore, that its successor committee "may wish to consider following up on these matters during session 6 and undertaking continued scrutiny of the regulation, performance and sustainability of Scotland’s aquaculture sector".

The Rural Affairs and Islands (RAI) Committee considered the issue of salmon farming on a number of occasions early in Session 6. It took evidence from Professor Russel Griggs on his independent review of regulatory process for aquaculture on 22 June 2022. It also held a preliminary evidence session on the Scottish Government's progress in implementing the REC Committee recommendations with the Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands on 10 May 2023.

In 2023, the RAI Committee agreed to undertake a follow-up inquiry into salmon farming at the earliest opportunity and this inquiry commenced in April 2024. The RAI Committee's inquiry focused on the implementation of the main recommendations made by the REC Committee, spread across four key themes:

fish health and welfare;

environmental impacts;

interactions between wild and farmed salmon; and

salmon farm consents and planning.

The Committee took evidence from a range of regulators, stakeholders, fish farm producers and the Scottish Government between June and October 2024. Further information about the evidence sessions is set out in Annexe B.

In addition, the Committee undertook a fact-finding visit to Oban on Sunday 22 and Monday 23 September. The Committee hosted a community engagement event on salmon farming with local stakeholders; visited the marine research facilities at the Scottish Association for Marine Science and visited the Dunstaffnage fish farm operated by Scottish Sea Farms.

The Committee thanks all those who provided written or oral evidence to inform the Committee's consideration of this issue.

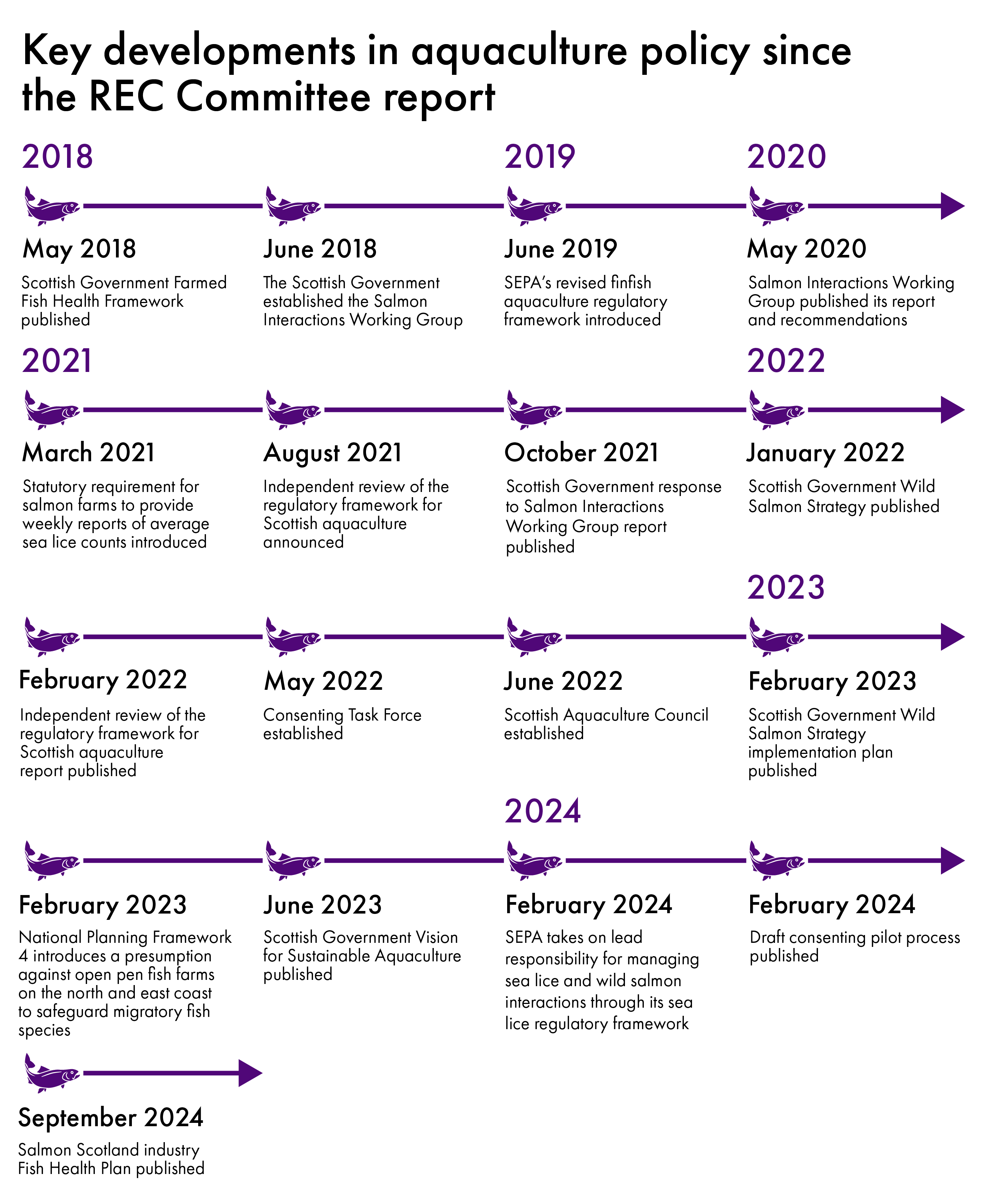

Developments in aquaculture policy since the REC Committee report

In the period since the REC Committee began its inquiry, a number of policy documents have been published and workstreams initiated. These are summarised below and illustrated in the accompanying graphic.

In May 2018, and prior to the conclusion of the REC Committee inquiry, the Scottish Government published its 10-year Farmed Fish Health Framework, a strategic plan developed by industry, academia, Marine Scotland (now known as the Scottish Government Marine Directorate), veterinary professionals, as well as regulatory and advisory bodies. The aim of the Farmed Fish Health Framework is:

To plan and be able to respond to new and developing challenges, the maintenance of high standards of fish health requires further strategic planning and co-ordinated action. This framework aims to provide the focus and mechanism to do this, and ensure the right people, organisations and resources come together to address these challenges efficiently. This framework looks to the long-term and therefore will continue to evolve as our knowledge of the fish health challenges and possible mitigation evolves.

The Farmed Fish Health Framework includes “clear reporting mechanisms with transparency and open communication embedded as key principles” in order to “ensure the momentum and drive exists to achieve real and concrete gains throughout the ten-year lifetime of the framework”.

In June 2018, the Scottish Government established the Salmon Interactions Working Group to evaluate policy, advice and projects relating to wild and farmed salmon sea lice interactions and to make recommendations, including a delivery plan of agreed actions and timescales, for a future interactions approach. The Salmon Interactions Working Group reported in May 2020 and the Scottish Government responded to the Salmon Interactions Working Group report in October 2021.

Since the REC Committee report was published, there has been a number of further developments relating to the salmon farmed fish industry in Scotland.

In 2019, SEPA published its finfish aquaculture sector plan with the aim of improving the environmental performance of the sector. SEPA also introduced a revised regulatory framework that provides additional controls around discharges from fish farms into the marine environment and new monitoring requirements of the surrounding seabed.

In 2020, the structure of the delivery mechanisms associated with the Farmed Fish Health Framework was reviewed to “help ensure future effectiveness and efficiency”. The Scottish Government announced that the “new governance structure in place and refreshed approach prioritises those work streams of Scotland’s Farmed Fish Health Framework which stand to make the most direct impact on fish health in Scotland”. The revised priority workstreams for the refreshed steering group for the Farmed Fish Health Framework were to:

develop a consistent reporting methodology for data collection and provide mortality data for farmed fish according to mortality cause;

look at the impact of climate change; and

encourage development of new medicines with the aim of increasing treatment flexibility within environmentally sustainable limits.

In August 2021, the Scottish Government invited Professor Russel Griggs to undertake “a review of the current regulatory framework for Scottish aquaculture, with a view to providing recommendations for future work which will improve its efficiency as well as inform any work on more fundamental reform”.

In January 2022, the Scottish Government published its wild salmon strategy. The strategy “sets out the vision, objectives and priority themes to ensure the protection and recovery of Scottish Atlantic wild salmon populations”. The Scottish Government published its wild salmon strategy: implementation plan 2023 to 2028 in February 2023 which sets out over 60 actions to be undertaken within the five-year period to achieve the vision that “Scotland's wild Atlantic salmon populations are flourishing and an example of nature recovery”.

In February 2022, Professor Griggs published ‘A Review of the Aquaculture Regulatory Process in Scotland’ with recommendations which he felt would “give the aquaculture sector an opportunity to develop in a way that allows commercial certainty within a controlled environment while taking into account the different status of each sector”. The Scottish Government accepted all recommendations in principle.

In May 2022, in response to the findings of Professor Griggs’s review of aquaculture regulation, the Cabinet Secretary announced the creation of a consenting task group “to identify an efficient and effective aquaculture consenting process, which enables appropriately informed regulatory decisions to be made as quickly as possible” with a particular task of piloting “new measures to achieve an improved, multilateral consenting process framework”. These pilots are currently running in the Shetland and Highland council areas.

In June 2022, the Scottish Aquaculture Council was established as a cross-stakeholder group “to respond to the unique benefits, opportunities and challenges of the salmon, trout, shellfish and seaweed farming sectors”.

In July 2023, the Scottish Government's 'Vision for Sustainable Aquaculture' was published which “describes the Scottish Government's long-term aspirations to 2045 for the finfish, shellfish and seaweed farming sectors, and the wider aquaculture supply chain”.

In September 2024, Salmon Scotland published the industry's 'Fish Health Plan', which sets out “what we do to protect the health and welfare of our fish, and how we will go further into the future”.

A glossary of organisations referenced throughout the report can be found in Annexe C of this report. A list of key terms used in the context of salmon farming and the production process can also be found on Scotland's Aquaculture website.

Section 2 - fish health and welfare

The REC Committee identified fish health and welfare as a “significant challenge to the salmon farming industry in Scotland” and, as part of its inquiry, considered issues around mortality, sea lice and the use of cleaner fish. It also examined how data on these matters were collected and reported by industry and regulators.

Farmed fish mortalities (recommendations 9 and 10)

Background

The 2018 Farmed Fish Health Framework stated that mortality "has many causes and is a primary area of focus for fish farming businesses” and recognised the “deterioration (in the years to and including 2017) in farmed fish survival in Scotland”. The Farmed Fish Health Framework set out the Scottish Government's commitment to “ensure that the industry, Government and principal regulators agree ambitious targets to achieve a significant and evidenced reduction in mortality for salmon and trout, which will be world-leading and based on international comparisons of major farmed salmonid producing nations”.

In its letter to the REC Committee, the ECCLR Committee expressed concerns about increased mortalities which it felt “the industry and regulators appear to be incapable of reducing”. It also stated that the same mortality levels “would not be considered acceptable in other livestock sectors”.

The REC Committee report stated that "the Committee considers the current level of mortalities to be too high in general across the sector and it is very concerned to note the extremely high mortality rates at particular sites" (recommendation 9). Recommendation 10 welcomed the Scottish Government's commitment in the Farmed Fish Health Framework to agree “ambitious targets”.

The REC Committee report made a number of recommendations calling for regulators to be given powers and “practical actions” to use in the event of high mortality levels. The REC Committee said it was “strongly of the view” that "no expansion should be permitted at sites which report high or significantly increased levels of mortalities, until these are addressed to the satisfaction of the appropriate regulatory bodies" (recommendation 9). The REC Committee recommended that "there should be a process in place which allows robust intervention by regulators when serious fish mortality events occur". This included appropriate mechanisms "to allow for the limiting or closing down of production until causes are addressed" (recommendation 10).

In its response to the report, the Scottish Government acknowledged "that performance across the sector is variable”. The then Cabinet Secretaries also stated that “one of the key challenges will be to develop a well-resourced research base to investigate causes of emerging disease and make the epidemiological analysis required to identify options for prevention and control as quickly as possible”.

In her 2023 update to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary stated that “good progress has been made through the Farmed Fish Health Framework in identifying and ranking the main causes of mortality into ten overarching categories”.

Committee consideration

Mortality figures and targets

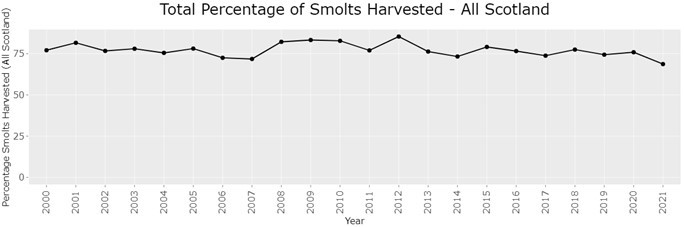

In a letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands to the Convener, 27 November 2024, the Scottish Government provided the latest mortality figures for smolts harvested across fish farms in Scotland. The figures show that, since the REC Committee report was published, the average rate of mortality as a percentage of salmon smolts harvested has remained at around 25%.

Information on Salmon Scotland’s website explains that the survival rate of farmed salmon is much higher than in wild salmon populations. It states that “Scottish Government data from the survey traps on River Dee tributaries (on Scotland's east coast) show that, even of the fish which survive from hatching to going to sea, the number returning to breed is below 2%” whereas “the annual average survival rate achieved for post-smolt farmed Scottish salmon is 85.5%, or 17 out of every 20 farmed salmon (14.5% mortality)".

Evidence from Animal Equality UK, however, argued that making a direct comparison between the survival rates of wild and farmed fish was “misleading” because high mortality rates in wild salmon “are part of an ecological balance, with predators and environmental factors shaping populations”, whereas farmed salmon “exist in controlled environments where high mortality rates often result from preventable causes like disease outbreaks, sea lice infestations, and farming practices”.

The Committee discussed the mortality rates with witnesses. Some witnesses, such as the Fish Health Inspectorate, referred to the aquaculture production survey figures which show that mortality as a percentage of salmon smolts harvested has remained at around 25%. The Fish Health Inspectorate acknowledged that the latest survival figures were less than in previous years but asserted that, “in the long term, there is still a fairly straight line for survival". Salmon Scotland indicated that survival figures from August were the best reported for five years and considered this a sign that "things are actually moving in the right direction".

Other witnesses, however, suggested these figures do not represent the full picture. The Coastal Communities Network referred to information extrapolated from biomass data published by SEPA which estimated 17.5 million fish had died in 2022, a figure significantly higher than numbers reported in 2018.

The Committee also heard about industry-reported mortality statistics which have recorded cumulative mortality rates as high as 80% over a production cycle on individual farms. For example, mortality data published by Salmon Scotland for August 2024 indicated a farm in Culnacnoc recorded an end-of-production-cycle mortality rate of 86.8%. Animal Equality UK suggested that the number of farms reporting death rates of above 50% had increased between 2018 and 2023.

When asked about mortality levels, the Cabinet Secretary stated that mortality rates have stayed relatively consistent “at a level of about 25%”. She went on to say that, “of course, that is not where we or the industry want those figures to be, but dealing with mortality is always difficult, because it is a really complex issue to try to address”.

The Committee considered the issue of targets for farmed fish mortality, as committed to in the Farmed Fish Health Framework and welcomed by the REC Committee. Professor Simon MacKenzie from the Institute of Aquaculture at the University of Stirling said mortalities of 17 million fish was "not a sustainable practice" and that "the targets that need to be set, and even the aspirations of what are acceptable mortalities in that food production system, have to be debated". The Coastal Communities Network pointed out that:

… nobody sets an upper limit for mortality. There is no figure for the maximum acceptable mortality. The Government will say that farms should work towards the lowest possible figure. In Druimyeon Bay, where it was 82%, that was the lowest possible figure, so that is apparently acceptable to the Government and to RSPCA Assured. There is no KPI that gives a maximum mortality rate.

The Cabinet Secretary did not want to be drawn into a discussion with the Committee about the issue of targets for mortality. She told the Committee that “I do not want to get into that— the Committee asked me during my previous appearance about what an optimum target would be, but I do not think that that is a helpful conversation to have”.

Causes of mortality

The Committee heard evidence which emphasised the complex factors causing farmed fish mortality, many of which are outwith the control of industry as a whole and its fish farmers individually. The Farmed Fish Health Framework steering group identified 10 causes of mortality of farmed salmon.i

The impact of climate change was discussed with the Committee. Increased water temperatures resulting from climate change were identified as having a particularly damaging effect on the sector, through placing increased stress on farmed populations and creating enhanced conditions for disease and parasites. Professor Sam Martin from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Aberdeen explained that mortality was cyclical, with higher levels expected in the warmer temperatures of the summer before reducing dramatically in the winter when water temperatures were colder and, therefore, parasites could be “cleared out”. He added, however, that recent warmer winters have not cleared out the parasites and, together with an on-going gill health issue with other compromising factors, this has resulted in high mortalities.

The Coastal Communities Network highlighted the Scottish Government's own findings on the link between water temperature, biomass and mortality, emphasising the predictability of these factors. It told the Committee that “government scientists found that 81% of the variation in mortality can be predicted by the previous minimum winter temperature and the biomass of fish”. It told the Committee that higher temperatures and increased biomass directly correlate with rising mortality rates. Comparing regions, the Coastal Communities Network pointed out that waters in Argyll and the Western Isles are significantly warmer than in Shetland or Orkney, which is reflected in mortality rates: Argyll reported 32%, the Western Isles 38.8%, Shetland 18.1% and lower rates in the north-west. The Coastal Communities Network highlighted these figures were above Norway's mortality rates.

During the Committee's visit to the Scottish Association for Marine Science in Oban, the Committee heard about the application of hydrodynamic and environmental computer models which use real data to predict how parameters in the marine environment will change over time. This included predictions of ocean current and flow, weather, sea lice dispersal, harmful algal blooms and the environmental footprint of fish farm sites. Researchers also explained how they are working on collaborative modelling research of sea lice dispersal aimed at improving sea lice dispersal monitoring and modelling techniques to predict distribution of sea lice in Scottish sea lochs.

Industry representatives agreed that continued fish mortality is a consequence of unique environmental factors arising over recent years. Scottish Sea Farms highlighted the impact of La Niña over recent years, followed by El Niño in 2023, which has created new problems for the industry such as the influx of micro-jellyfish (which can cause mortality through their harmful effects on gill health) in Scotland in 2022.

The Cabinet Secretary also noted the development of new challenges in recent years and mentioned work was being progressed to "get in front of whatever is coming next" through investment in science and technology. To that end, she pointed to £1.5m funding provided by the Scottish Government to the Scottish Aquaculture Innovation Centre to support its work in horizon-scanning around algae blooms in order “to predict where that might happen again”.

Provision for “practical action” in the event of high mortality

The Committee heard some support for no expansion (recommendation 9) or a mechanism to enable “robust intervention by regulators” (recommendation 10) when serious fish mortality events occur at a particular site. Professor MacKenzie argued that the current approach to preventing mortality "needs to have some bite behind it, otherwise change will not happen". The Coastal Communities Network told members that “mortality has to come down—we all agree with that—but there were no sanctions for having [a high] mortality rate”.

Others, however, warned of the dangers and difficulties in putting in place a threshold for intervention which didn’t consider the wider context around a high mortality event or that the causes of mass mortality are often outwith industry’s control. Dr Rachel Shucksmith, a marine spatial planning manager at the University of the Highlands and Islands, advised “a level of caution because some mass mortality events—say, those that are driven by algae or by a jellyfish bloom—might occur at a locality then not occur again for 20 years”. Dr Shucksmith went on to give an example from Shetland where “I observed that a particular species of jellyfish bloomed and caused mass mortality, but that species has never been seen to bloom again, and so it has never impacted on that locality again”. She concluded that “although a one-off mortality rate was very high there, preventing aquaculture at that site in future years would not have been necessary”.

Several stakeholders highlighted concerns that regulatory responsibilities around mortality were opaque and poorly coordinated between bodies. OneKind said there was a lack of clarity in how the Fish Health Inspectorate, the Animal and Plant Health Agency and local authorities undertake their functions and that many mass mortality events were not being referred by them for further investigation.

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary why these mechanisms had not been developed. The Cabinet Secretary said she was satisfied the Fish Health Inspectorate has the appropriate powers to deal with mortality resulting from fish health issues and did not see how an intervention mechanism could effectively work. She told the Committee:

I struggle to see what the purpose of that would be. If, for example, an environmental challenge arises that could not be predicted, how does a farm deal with that? How does a farm deal with a situation that could lead to an increase in mortalities that is outwith its control?

When asked about any confusion about the different regulators’ responsibilities, the Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that “each organisation has a specific role that it has to undertake and specific laws and regulation that it has to enforce and monitor”. She emphasised the importance of “close collaboration between the different organisations in this space” and that the Fish Health Inspectorate and Animal and Plant Health Agency have been in discussions about how to collaborate better on those issues.

The Committee is disappointed by figures showing that mortality has not improved since the 2018 REC Committee inquiry report. The REC Committee considered these mortality figures to be “too high”. The Committee also notes that mass mortality events have occurred at some farms since the REC Committee inquiry. These mass mortality events make it more difficult to interpret whether the trend in overall mortality figures have changed significantly.

The Committee also notes the Scottish Government's Farmed Fish Health Framework commitment to set “world leading” and “ambitious” targets to reduce mortality was not mentioned when the Farmed Fish Health Framework delivery mechanisms and workstreams were revised in 2020.

The Committee recognises the multiple and complex causes of mortality in farmed fish. In particular, the Committee notes the unpredictable, acute environmental events – such as algae blooms and micro-jellyfish in 2022 and 2023 – which have caused mass mortalities at some sites. The Committee recognises these environmental events are not within the control of industry as a whole and its fish farmers individually.

The Committee also notes that the frequency of these unpredictable, acute environmental events which cause mass mortalities may increase due to the impacts of climate change. Consequently, the Committee is concerned that preventing high mortality events is not currently within the operational capability of industry as a whole and its fish farmers individually.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government establish a research project focused on testing and improving the modelling of environmental conditions that are known to cause high mortality events on salmon farms. This research should aim to explore improvements in the capability to predict such events to provide early warning to industry and inform technological solutions and approaches to husbandry to mitigate high mortality events. This research should also consider whether the current collection and monitoring of environmental conditions around salmon farms is sufficient for computer modelling purposes and identify potential for improvements. The Committee asks the Cabinet Secretary to set out a timetable for establishing this research project in her response to this report.

The Committee notes the REC Committee recommendations for no expansion at sites with high mortality and for “robust intervention” when serious mortality events occur have not been implemented. The Committee also notes the Cabinet Secretary's view that a threshold for intervention precipitated by a high mortality event would fail to recognise the wider context or that some are caused by factors outwith the fish farm's control. At the same time, however, the Committee believes further action is needed to improve the governance of fish health and welfare on farms to address gaps in accountability and enforcement around mortality. The Committee recommends, therefore, the Scottish Government provide powers to the Fish Health Inspectorate (or another appropriate body) to limit or halt production at sites which record persistent high mortality rates. The Scottish Government should work with industry and regulators to agree appropriate criteria and mortality thresholds for the use of these powers.

The Committee also notes that, for some fish farms, the flexibility to relocate to more suitable sites would mitigate fish mortality. The Committee makes recommendations relating to this in section 5.

Mortality data (recommendations 11 and 12)

Background

At the time of the REC Committee inquiry, the Scotland's Aquaculture website published monthly biomass and treatment reports for all fish farms, including a figure in kilograms for biomass lost per month. There was, however, no mandatory requirement for industry to publish mortality data, although some producers published this on a voluntary basis. The Farmed Fish Health Framework set out a number of actions relating to data collection including to develop a consistent reporting methodology for collection of information on the causes of farmed fish mortality and to “develop a national approach to data-sharing and evidence-gathering that can enable evidence-based decision making, best practice and promote openness and transparency within the Scottish industry”.

Recommendation 11 of the REC Committee report stated it was essential that a consistent reporting methodology for farmed fish mortality should be developed to “provide an accurate, detailed and timely reflection of mortality levels including their underlying causes across the whole sector". Recommendation 12 called for “sufficiently robust” methodology for mortality reporting and stated the REC Committee was “strongly of the view” that reporting mortality data should be mandatory.

In their response to the Committee, the then Cabinet Secretaries said the Scottish Government would take into account the Committee's views as part of the Farmed Fish Health Framework workstream.

In her 2023 update to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary referred to the standardisation of mortality reporting across the sector and data publication as “a significant step forward both in terms of transparency and facilitating better understanding of the reasons for mortality”. She also ruled out mandatory reporting of additional mortality information, stating that “mortality reporting is not mandatory, mortality reporting thresholds exist and the fish farming sector publishes its own site-level information”.

The mortality data made available is summarised in the table below.

| Source | Information published |

|---|---|

| SEPA | Monthly (weight in kilograms) |

| Fish Health Inspectorate | Weekly (number of fish where reporting thresholds have been reached) |

| Salmon Scotland | Monthly mortality rate (percentage of the total number of fish on the farm each month), Cumulative mortality over full production cycle (percentage of fish that have died on a farm during the entire production cycle, given as a percentage of the total number of fish that were initially stocked on the farm), includes notes on cause identified. |

| Scottish Government Marine Directorate (fish farm production survey) | Survival rate (percentage) from smolt input to harvest by year class. |

Source: Salmon Scotland written submission

Industry currently provides voluntary reporting of mortality data to the Fish Health Inspectorate for mortality above the thresholds set out in the Code of Good Practice for Scottish Finfish Aquaculture (1.5% for farms with a site average weight of less than 750g; 1.0% for farms with a site average weight of more than 750g).

Committee consideration

Some stakeholders acknowledged that industry has made significant improvements to the mortality data it makes available. Professor Martin told the Committee that "the industry has made big efforts, through Salmon Scotland, to publish all the mortality data monthly for every site in Scotland". Scottish Sea Farms stressed the accuracy of the mortality data:

All the paperwork that is associated with it [farmed fish mortality], from the recovery to the quantities, is fully recorded, fully audited and inspected by the Fish Health Inspectorate and by other organisations, including the Animal and Plant Health Agency. That should be borne in mind.

The Committee was also told, however, that improvements could be made to the way that information is presented. For example, RSPCA Scotland noted that there was a difficulty understanding mortality data “because the reporting is still messy”. Salmon Scotland also acknowledged the challenges with interpreting the data, agreeing that “while all data is accurate, it can be confusing to understand what is published, by who, and why”.

In particular, a number of stakeholders queried why SEPA published mortality data based on biomass tonnage rather than individual fish as this makes it difficult to compare with other data sets. Environmental groups argued that mortality data should be reported as individual fish because using weight-based mortality was an unfitting method of measuring fish health and welfare. The Coastal Communities Network said SEPA used to collect mortality data on the basis of individual fish but that “it stopped doing so in 2020, without explanation, and now only publishes mortalities by weight".

When asked about this, SEPA stated that it collects weight-based data because biomass is the metric used for discharging its specific regulatory responsibilities around aquaculture.

Other witnesses felt that more detail should be provided relating to the causes of mortality. For example, RSPCA Scotland noted that some reasons given, such as 'gill disease', were "super vague".

The Coastal Communities Network raised specific concerns that the data to be reported to the Fish Health Inspectorate was limited. The Coastal Communities Network noted its concern that the Fish Health Inspectorate's mortality data excludes all deaths below weekly thresholds of 1.5% or 1% of salmon in each farm (depending on their weight); any smolts that die in their first six weeks at sea (as so many die when they are first put in salt water). It also said “these figures exclude mortality in the earlier freshwater stage, during which more than 30% of fish often die, before the survivors are put to sea”.

RSPCA Scotland also acknowledged in its evidence that the mortality information it received from industry as part of similar reporting arrangements was not a “full data set”.

In relation to the detail provided about the causes of mortality, the Cabinet Secretary highlighted the work done through the Farmed Fish Health Framework to standardise reporting across farms based on 10 defined causes of mortality. She also acknowledged that “further improvements could still be made in how the overall data is presented” and added the issue “is something that we have discussed, and I think it would be helpful for us to provide an explainer of how all the different categories of information are used”.

In relation to the criticisms levelled at its data, the Fish Health Inspectorate accepted that it was not a comprehensive data set but argued "it is all mortality that is considered to be significant". It claimed the industry provides "a spread of data throughout the year and throughout the country, which gives us the opportunity to look at trends".

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed she was satisfied with current reporting requirements and considered it to be proportionate to the purpose the information was used for by regulators.

The Committee notes the actions taken by industry since 2018 to improve the quality of mortality data published. The Committee is concerned by the lack of consistency in how mortality data is collected and published, however, and welcomes the Cabinet Secretary's commitment to make further improvements. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government must publish comprehensive, consistent and transparent mortality figures that include the number of fish at a farm, the freshwater mortality and seawater mortality, per facility, with accurate numbers of dead salmon, wrasse and lumpsuckers per week and with cumulative mortality totals at the end of each cycle.

The scope for improvement in the information provided relating to the causes of mortality was also raised with the Committee. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government publish an annual fish health report detailing the health and welfare status of all farmed aquatic finfish, including wild caught wrasse, in Scotland. These reports should include both annual statistics on, and the causes of, finfish mortalities.

The Committee also heard concerns regarding the information collected by the Fish Health Inspectorate and notes that reporting of mortalities under the Code of Good Practice for Scottish Finfish Aquaculture is currently voluntary. The REC Committee recommended that reporting should be mandatory but the Cabinet Secretary has confirmed the Scottish Government's view that the current reporting requirements are sufficient and proportionate. Given the concerns raised in evidence relating to the Fish Health Inspectorate information, however, the Committee supports the REC Committee recommendation for mandatory reporting of mortalities to the Fish Health Inspectorate. The Committee suggests a reporting mechanism would not be overly onerous given industry already collects this data for the purpose of on-site audits. The Committee believes that a more robust reporting regime would bring greater transparency to the industry, support the Fish Health Inspectorate's oversight of farm activities, and align with new reporting criteria around sea lice.

Farmed fish welfare

Background

Whilst the REC Committee did not specifically consider, and make recommendations about, farmed fish general welfare, the issue was discussed during this Committee's inquiry.

The Animal and Plant Health Agency has statutory responsibility for regulating fish welfare in accordance with the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006 and for investigating welfare issues occurring at salmon farms. In a letter to the Committee, it said "the Scottish Ministers issue guidance documents on welfare which identify good practice and support regulatory action when standards fall short of good practice; there is no such document for farmed fish".

Responsibility for initiating prosecutions for animal welfare offences at fish farms is a matter for local authorities.

Animal welfare standards at farms are also assessed through voluntary accreditation services provided by RSPCA Assured. Wildfish raised a concern with the Committee about a conflict of interest in roles and responsibilities between RSPCA Scotland and RSPCA Assured with respect to their relationship to the salmon industry. In a letter to the Committee, dated 5 June 2024, RSPCA Scotland confirmed to the Committee that it was a separate charity to RSPCA Assured and noted that both had different organisational structures and charity numbers.

Farm management and husbandry practices that promote fish welfare are set out in the industry's Code of Good practice for Scottish Finfish Aquaculture. The Committee understands the Code is expected to be renewed next year.

Committee consideration

The issue of the welfare of farmed salmon was raised during the Committee's evidence gathering. Industry representatives emphasised the importance of promoting good fish welfare in the salmon they produce. Cooke Scotland explained how farms conduct regular welfare assessments to examine the physical condition of fish. Bakkafrost Scotland told the Committee that the sector has made "fundamental changes to our welfare practices over the past five years", including moves away from reactive methods of assessing fish welfare to “more proactive and preventative means of looking after our fish”. Industry representatives gave the example of £1b worth of investments made in new equipment to improve fish health and welfare on their farms through new monitoring and camera technologies, as well as new treatment wellboats.

Other witnesses set out their concerns about the impact of salmon farming on salmon welfare. RSPCA Scotland argued that "fish welfare is improving, but our knowledge is still developing".

Professor Lynne Sneddon from the University of Gothenburg told the Committee there is evidence that salmon are capable of experiencing pain, which significantly affects their welfare. She told the Committee that “if an animal is in pain, it is definitely experiencing poor welfare” and noted that pain has measurable impacts on salmon behaviour, physiology and neurobiology. To assess welfare, she suggested monitoring behavioural indicators such as feeding habits, swimming patterns, use of cage space and signs of aggression. She also highlighted that morphological markers, such as lesions or damage to gills, eyes or fins, are also critical. Additionally, she advocated sub-sampling fish to evaluate physiological traits and detect disease or parasites and emphasised that “a wealth of information” exists to ensure farmed salmon can live good lives with maintained health, adding, “action should be taken if, say, 10% of the fish start exhibiting signs of aggression”. The Committee heard, as part of its visit to Dunstaffnage fish farm, how staff are trained to monitor behavioural indicators when undertaking welfare assessments.

The use of treatments such as Thermolicers (a treatment whereby salmon are bathed in lukewarm water to remove sea lice) were highlighted as detrimental to fish welfare. Wildfish told the Committee that “when you run fish through physical treatments, you have welfare issues and you also weaken the fish and put compromised fish back into the water, which contributes to rising mortality”. Professor Sneddon also expressed concerns about the impact of Thermolicers and said use of the treatment had shown to subject fish to conditions beyond their pain thresholds. She said:

I have spoken to people in the industry who tell me that the animals do not feed for several weeks after thermal treatments, so they are, in effect, weakened or in a poor welfare state. We should not allow such treatment, because it causes pain and it significantly impairs their behaviour and welfare. They also do not feed for quite a long time afterwards.

Industry representatives agreed that treatments for sea lice could damage fish health and welfare.

The Committee is aware that farmed fish are covered by general animal welfare protections established in the 2006 Act, which makes it an offence to cause unnecessary suffering and prohibits mutilation, cruel operations and the administration of poisonous drugs or substances as defined under the 2006 Act. Several stakeholders, however, noted that farmed fish do not have species-specific statutory welfare standards or official guidance issued under the 2006 Act like other terrestrial farmed animals – such as cattle, chickens, gamebirds, pigs and sheep – and that addressing this would deliver improvements in standards and their enforcement. The Animal Law Foundation noted official guidance would “ensure that the laws are being enforced effectively and that the welfare of the fish on fish farms is being treated as a priority”.

RSPCA Scotland said:

Scotland has no species-specific legislation for the welfare of fish. Fish are not even covered by the legislation in the UK or Scotland around welfare at the time of killing. There is almost nothing in that regard, so the fact that our [RSPCA Assured] standards even exist is going above and beyond. We have standards around the maximum time that fish can be out of water, around stun and slaughter and around how to handle fish. None of those issues are covered by legislation.

The Committee questioned the Cabinet Secretary as to why there were no specific welfare standards for farmed fish under the 2006 Act. The Cabinet Secretary said she is comfortable sufficient protections are in place for promoting animal welfare in salmon farming. She also said she is "open to consider where any potential enhancements to animal welfare can be made" and "to consider the role of Animal and Plant Health Agency when it comes to strengthen their role of when it comes to protecting fish welfare". A Marine Directorate official said there is an "ecosystem of understanding" across various documents that set out indicators of good practice around fish welfare that are drawn upon by the Animal and Plant Health Agency when undertaking their regulatory responsibilities.

The Committee understands the importance of fish welfare to industry in marketing Scottish salmon as a premium product and is supportive of the investments made by the sector in promoting good fish welfare. It notes, however, concerns about whether some of industry's practices are proportionate to this aim, including the use of mechanical techniques such as Thermolicer and Hydrolicer, as well as chemical and medicinal treatments that can stress the fish.

The Committee is concerned that farmed fish do not have specific statutory welfare standards or official guidance under the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006. Specific standards and guidance are currently set through voluntary mechanisms, such as accreditation and industry's Code of Good Practice for Scottish Finfish Aquaculture. It is clear to the Committee that the statutory regime must keep pace with knowledge about farmed fish welfare to set a baseline for farm standards.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government bring forward additional regulations and official guidance under the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006 Act in order to set specific baseline standards for the welfare of farmed fish. This should dovetail into the upcoming review of industry's Code of Good Practice to ensure this provides adequate guidance on how statutory requirements should be achieved. The Committee also recommends official guidance must take account of industry's need to balance treating their fish in order to meet regulatory standards for sea lice with the potential unintended consequences this may have for fish health and welfare.

Sea lice (recommendations 15 and 16)

Background

Sea lice occur naturally in the marine environment and live on the skin of fish, causing damage which can lead to infection, stress and immune suppression with greater susceptibility to secondary infection and disease. The REC Committee inquiry considered the treatment of sea lice and the impact of sea lice and treatment measures on the environment. The inquiry also considered the impact of sea lice infecting wild salmon passing fish farms on their migratory routes; this is considered in more detail in section 4.

Salmon producers provide data on the amount of sea lice prevalent at their sites and report their counts to the Fish Health Inspectorate, who collect and monitor this data on behalf of the Scottish Ministers. The Fish Health Inspectorate has statutory powers to inspect sites for sea lice to ensure compliance with required farm management protocols for the treatment of sea lice. The Fish Health Inspectorate can also require farms to take action to reduce their sea lice counts if they exceed certain thresholds.

At the time of the REC Committee inquiry, sea lice numbers only needed to be reported to the Fish Health Inspectorate if they exceeded the threshold of an average of three adult female lice per fish; at this point, the Fish Health Inspectorate would increase monitoring of the farm. Above an average of eight adult female lice per fish, the Fish Health Inspectorate would intervene to take action to reduce sea lice levels.

The REC Committee inquiry identified sea lice infections as a “significant challenge” facing the industry and concluded “it is clear that the industry has not as yet identified a means to fully and effectively deal with this parasite”. The REC Committee referenced the announcement of a dedicated sea lice workstream as part of the Farmed Fish Health Framework and noted a “shift by the industry from medicinal treatment to a more balanced strategy, utilising a range of control methods”.

The REC Committee noted the evidence relating to the different thresholds for reporting and intervention purposes and agreed that the Farmed Fish Health Framework workstream provided an opportunity to remove confusion around this issue and develop proposals that are appropriate to both industry and regulators. The REC Committee report recommended these threshold levels for reporting sea lice counts "should be challenging and set a threshold that is comparable with the highest international industry standards" (recommendation 15). Recommendation 16 called for any proposals from the Farmed Fish Health Framework workstream to “make compliance and reporting a mandatory requirement”.

In the Scottish Government’s response to the REC Committee report, the then Cabinet Secretaries referred to the on-going work of the Farmed Fish Health Framework workstream and the Salmon Interactions Working Group.

In 2021, the threshold levels for increased monitoring or intervention by the Fish Health Inspectorate for sea lice were lowered following the outcome of Marine Scotland's review of its compliance policy for sea lice. They were reduced to two adult female lice per fish leading to increased monitoring by the Fish Health Inspectorate, and six adult female lice per fish (or above) leading to intervention by the Fish Health Inspectorate.

The Fish Farming Businesses (Reporting) (Scotland) Order 2020 introduced mandatory weekly reporting of sea lice counts in 2021; where no count is conducted, the reason must be given and the data is published. In evidence, the Fish Health Inspectorate told this Committee this gives the Fish Health Inspectorate “a far greater oversight of what is occurring on farms".

In 2019, a commitment was made to further reduce the monitoring and intervention levels for Fish Health Inspectorate engagement to an average of two and four sea lice per fish respectively.

In her 2023 update to this Committee, the Cabinet Secretary referred to the 2019 commitment to further reduce the monitoring and intervention levels for Fish Health Inspectorate engagement. She stated that, as the “policy context within which the fish sector is operating has changed significantly”, the Scottish Government would not pursue the commitment at this time.

Committee consideration

Some stakeholders felt the reduced thresholds for reporting and intervention purposes were neither sufficiently challenging nor comparable with the highest international industry standards. The Coastal Communities Network argued that Norway is an example of international best practice in protecting wild fish stocks from the effects of sea lice from farmed salmon. Norway has lower sea lice limits than Scotland, with mandatory culling at farms reporting an average of above 0.2 adult female sea lice per salmon throughout the spring and 0.5 adult female sea lice per salmon for the rest of the year.

Industry representatives highlighted the “higher risk of harm and the potential for mortality” associated with lower threshold levels. Scottish Sea Farms told the Committee that, “if the sea lice threshold burden for intervention was lower, we would have to intervene and do a treatment on a population of fish when that would not be for their welfare—it would not be in their interest”.

The methodology used by farms when carrying out sea lice counts was raised with the Committee. The methodology used is to sample a minimum of five fish each from five marine pens, if the number of marine pens at a site is above five, or a minimum of five fish each from all marine pens, if the number of pens is below five. Some environmental stakeholders argued this methodology does not provide an accurate reflection of the sea lice apparent in cages. The Coastal Communities Network argued that “you need thousands of fish counted each week to give a meaningful, relatively statistically accurate figure for lice in a farm”. Both industry representatives and the Fish Health Inspectorate explained the methodology for counting was well-established and based on "the minimum requirement to achieve a meaningful count". Automated counting through developments in artificial intelligence was identified as offering a potential solution to allowing a more sizeable and rapid counting of sea lice counts in the future.

Some stakeholders highlighted concerns over the number of 'no count' weekly returns whereby data were not provided by farms. Wildfish said that its analysis of published figures indicated that nearly 20% of submitted data since 2021 had been no counts. The Atlantic Salmon Trust suggested that “the Fish Health Inspectorate investigate robustly when repeated no counts occur from a particular business, and that this information is made public”.

Industry representatives explained that they were sometimes unable to collect data due to bad weather or because fish were being treated. The Fish Health Inspectorate agreed that some ‘no counts’ were due to legitimate reasons but that it is "attempting to minimise” the number of no counts due to fish being subject to treatments or when stocks are being held for harvest.

The Committee notes that changes have been made to strengthen the regime for sea lice reporting and intervention and considers the reduced reporting thresholds a step towards delivering the REC Committee recommendation for levels to be “challenging and of the highest international standards”.

The Committee welcomes the introduction of mandatory weekly reporting of sea lice counts under the Fish Farming Businesses (Reporting) (Scotland) Order 2020 which seeks to implement the REC Committee's recommendation 16. The Committee also notes, however, evidence relating to the number of ‘no counts’. Whilst members recognise there will be weeks when it is not possible for fish farms to undertake a sea lice count, the reporting mechanism needs to be robust enough to be comprehensive and accurate in order to inform the Fish Health Inspectorate's oversight. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government introduce stricter conditions on the accepted reasons for no counts with regards to stock that is subject to treatments and being held for harvest and that it updates relevant guidance and enforcement approach accordingly.

Publication of information on salmon farming (recommendations 22, 23 and 24)

Background

The REC Committee inquiry considered how a range of data relating to fish farming was collected, recorded, published and monitored.

The REC Committee was “strongly of the view” that "there needs to be significant enhancement of the way sea lice data and other key information […] is presented". The Committee called for "a comprehensive, accessible reporting system of a similar standard to that which is already in operation in Norway should be introduced in Scotland" (recommendation 22). Recommendation 23 called for this reporting system to hold "a suite of data available covering mortality, sea lice infestation, medicine application and treatment information". The REC Committee recognised there would be a cost involved and recommended “the associated costs should be borne by the industry” (recommendation 24).

The Scottish Government said, in response to the REC Committee report, that these recommendations would be considered as the Farmed Fish Health Framework was progressed and that this workstream would provide an "opportunity to declutter the landscape".

In her progress update to the Committee in 2023, the Cabinet Secretary said the Scotland's Aquaculture website had been created to collate and publish key data.

Committee consideration

Industry representatives said that progress has been made by investing in enhanced data collection tools and improving transparency. Salmon Scotland said that "significant amounts of data and information are available for our sector, all in the public domain – more so than other salmon farming sector around the globe and also compared with other domestic farming sectors".

Wildfish questioned the quality of the information published, it told the Committee:

[…] it is also worth reiterating that the counts are self-reported and unverified, which is significant because SEPA bases its sea lice framework on that data. We struggle to see how it can do that with such a big data gap and without verifying the counts that come in from the farms.

Both SEPA and Fish Health Inspectorate said they were transparent in publishing information about their regulatory activities. SEPA noted that data made available on the Scotland's Aquaculture website has "grown in volume and subject matter over the period since 2019", including the publication of all its data relating to medicine use and biomass compliance as well as the results of its seabed surveys. The Fish Health Inspectorate similarly noted that "for every case that we carry out, a complete case record—all the information that we have collected on site, the observations of the inspector and the report that has gone to the farmer—is placed in the public domain".

Academics agreed that noticeable progress had been made to increase the volume of data around salmon farming in the public domain. Professor MacKenzie told the Committee that the amount of available data now, compared with 10 years ago, “is massive—it is orders of magnitude higher than it was".

Nevertheless, some stakeholders considered that, whilst more information is available in the public domain, this information is poorly coordinated and not presented in an accessible way. RSPCA Scotland characterised the website as "messy and clunky" but added that "at least the data is coming in, which is an improvement on what was happening six years ago". Dr Helena Reinardy from the Scottish Association for Marine Science said that, whilst there had been efforts to integrate and present data sets on the Scottish Aquaculture website, "we are not yet at a place where we can easily access the data".

The Fish Health Inspectorate agreed that data " does not necessarily all sit in one place". It suggested that "if more resource to produce a different information technology system were available, we—by which I mean the regulators of aquaculture—could make that data more accessible".

A number of witnesses highlighted how aquaculture data in Norway is published on a system called BarentsWatch, an information hub which collates and develops data on a number of fish health indicators from fish farms across Norway. The BarentsWatch system was referred to as more user friendly and more frequently updated than its Scottish equivalent.

The Cabinet Secretary recognised that “more work could be done overall on the ease of accessibility of that information, but that comes back to a prioritisation discussion”. She committed to the Scottish Government providing an explanatory document to navigate the available information, but that “a website or information technology overhaul could be a very expensive process”.

The Committee notes the development of the Scotland's Aquaculture website and the consensus that the suite of data called for by the REC Committee is now publicly available. The Committee also, however, agrees with the frustration expressed by stakeholders that the website is difficult to navigate and information is not presented in an easily understandable format. The Committee is not satisfied that an explanatory document will wholly address these concerns and recommends the Scottish Government prioritises upgrading and improving the Scotland's Aquaculture website to make data more accessible and user friendly.

The Committee notes the REC Committee's view that the costs associated with developing the suite of data should be borne by the industry and that it called on the Scottish Government to discuss with industry representatives how this might be achieved. This Committee recommends that the Scottish Government takes forward recommendation 24 as soon as practicable.

Use of cleaner fish (recommendations 26 and 28)

So called ‘cleaner fish’, such as lumpfish and wrasse, are natural sea lice predators and have been increasingly used in salmon farming as an alternative method of controlling sea lice to chemicals. Lumpfish are farmed in hatcheries; wrasse are either farmed or wild caught.

Background

The ECCLR Committee stated in its report that the potential implications of increased use of cleaner fish in salmon farming are unclear. This was supported by recommendation 26 of the REC Committee report, which found an "urgent need for an assessment of future demand as well as all associated environmental implications of the farming, fishing and use of cleaner fish". Recommendation 28 also called on the Scottish Government to "consider the need for regulation of cleaner fish fishing to preserve wild stocks and avoid negative knock-on impact in local ecosystems".

Responding to the REC Committee report, the then Cabinet Secretaries pointed to a number of voluntary control measures in place for wild caught wrasse which "include minimum and maximum landing sizes, limits on the number of traps that can be used, and the recording of catches". They noted that work was underway to gather data amongst the commercial wrasse fisheries and salmon farming sectors "to further understand the wild fishery for wrasse in Scotland and ensure its sustainability". Finally, they noted that the working group for cleaner fish as part of the Farmed Fish Health Framework "will also continue work to map out future wild caught cleaner fish demands, as the industry moves to significantly increase production of hatchery reared cleaner fish for use in salmonid farming".

In 2023, the Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that new mandatory measures for wild wrasse harvesting had been introduced in 2021 which "included additional data collection requirements upon each vessel". She also noted that "additional control measures may be implemented as further evidence becomes available".

Committee consideration

The Committee heard concerns about the welfare of cleaner fish. Professor Sneddon told members that almost a third of cleaner fish die within a few weeks of being deployed in marine pens. The Fish Health Inspectorate agreed with this concern, commenting that "the mortality that occurs in cleaner fish deployed in aquaculture cages is higher than we would like". Wildfish told the Committee that all cleaner fish were culled at the end of production cycles and the Coastal Communities Network made the same point, telling the Committee that one farm “put in 182,000 lumpsuckers and 31,000 wrasse and they all died” and that “that happened in just one production cycle—a year and a half, basically”.

Professor Sneddon told the Committee about other welfare impacts for cleaner fish:

Overall, very few studies are looking at what happens to individual lumpfish or wrasse when they go into sea cages, and there seems to be quite high mortality. Once they reach a certain size, they stop feeding on sea lice. They sit in the cage, and it is likely that they will be exposed to treatments—whether that is chemical or physical treatments—for salmon lice.

Salmon producers highlighted the improvements they have made to equipment and practices to improve the welfare of cleaner fish. Wester Ross Fisheries spoke about the ability to separate out the cleaner fish before treatments were carried out using upgraded wellboats. It also highlighted the use of kelp and other measures in marine pens to simulate the natural ecological conditions and diet of the species.

In terms of the sustainability of the practice, Mowi Scotland thought this was uncertain and indicated the sector is taking steps to increase its capacity for farmed wrasse.

When the Committee considered the amendments to the Joint Fisheries Statement on 6 November 2024, the Cabinet Secretary stated the Scottish Government had recently received new information regarding the implications of wrasse fishing on marine sites and features based on a University of Glasgow report commissioned by NatureScot. The Cabinet Secretary indicated she is expecting further advice from NatureScot on this matter. In correspondence to the Citizens Participation and Public Petitions Committee, in relation to petition PE2110 calling for a fisheries management plan for wild wrasse, she said that "in light of this evidence, we now intend to undertake an appropriate assessment, under the Habitats Regulations, for the wrasse fishery ahead of the next season opening in May 2025".

The Committee is aware that Environmental Standards Scotland received a representation raising a concern that the Scottish Government Marine Directorate was not complying with its legal duties under the Habitats Regulations. The concerns raised related to the lack of controls regarding fishing activities within protected areas and the likely wider ecological impacts on other protected features and/or species. Following enquiries by Environmental Standards Scotland, the Marine Directorate accepted that, in light of new scientific evidence, the potential for wider adverse impacts from this type of fishing should be assessed and it has committed to undertaking an appropriate assessment prior to the start of the next fishing season on 1 May 2025. Environmental Standards Scotland determined that this commitment satisfies the outcome sought in the representation; it undertook to monitor progress and, should an appropriate assessment fail to be completed within the agreed timescale, to review what further action is required.

The Cabinet Secretary also told this Committee about a package of evidence-gathering activities looking at the deployment of cleaner fish to enhance existing protections. She added that the Scottish Animal Welfare Commission is currently considering the welfare of cleaner fish.

In correspondence sent to the Committee on 9 December 2024, the Sustainable Inshore Fisheries Trust suggested that, although the report on wild wrasse fishing had been commissioned by NatureScot and despite the agency receiving the report in 2020, that it did not appear the Scottish Government was made aware of its contents until 2024. It said:

The importance of the report can be seen by the fact that upon its eventual receipt in 2024 – and because of its findings – the Scottish Government committed to conducting Habitats Regulations Assessments for the wrasse fishery within Special Areas of Conservation . This raises serious questions about why NatureScot, as the Scottish Government's statutory adviser, did not inform Marine Directorate in 2020 that such Habitats Regulations Assessments were required. That represents four years where the Scottish Government as a whole was in breach of the statutory requirement to conduct these assessments and to conduct them properly.

Although it is clear some welfare measures have been introduced relating to the use of cleaner fish since the REC Committee report, it is not clear whether the "urgent need for an assessment of future demand as well as all associated environmental implications of the farming, fishing and use of cleaner fish" has been met. Whilst the Committee welcomes efforts made by industry to meet the welfare needs of cleaner fish, members share the concerns raised by stakeholders about the ethics and welfare implications of the use of cleaner fish as a tool for sea lice management and, especially, around the high mortality rate. The Committee notes the Fish Health Inspectorate shares this concern.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government publish the University of Glasgow report commissioned by NatureScot as a matter of urgency. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government provide the further advice it is expecting from NatureScot and to publish the results of the Scottish Animal Welfare Commission review at the earliest opportunity and notify the Committee when that takes place.

The Committee is deeply troubled by evidence that suggests NatureScot waited four years before alerting the Scottish Ministers about the report's findings. Given the potential impacts from this delay, the Committee requests NatureScot and the Scottish Government provide urgent clarification to the Committee on this matter.

In addition, the Committee was assured by the Cabinet Secretary during its recent consideration of the amendments to the Joint Fisheries Statement that the Scottish Government could develop a fisheries management plan or take other action to protect a fish stock. The Committee notes the current petition PE2110 calling for a fisheries management plan for wild wrasse. Depending on the further advice it is expecting from NatureScot and the results of the Scottish Animal Welfare Commission review, the Committee recommends a fisheries management plan or other protective action should be developed as soon as practicable to ensure any wild wrasse are harvested sustainably.

Section 3 - environmental impacts of salmon farming

The REC Committee report identified environmental impacts as a significant challenge for the salmon farming industry. Its views were informed by the work of the ECCLR Committee, who reported that it was “deeply concerned that the development and growth of the sector is taking place without a full understanding of the environmental impacts”.

This report considers the REC Committee's recommendations regarding the environmental impacts of waste and discharges from salmon farms, and from the use of medicines.

Discharges from marine pen fish farms (recommendations 29 and 30)

Background

Research commissioned by the ECCLR Committee in 2018 found that waste products – such as faeces and uneaten feed – can reduce oxygen levels and create a smothering effect on the seabed whereby "the diversity of the community of seabed (benthic) animals is much reduced".

Accordingly, the REC Committee's recommendation 29 called for waste collection and removal to be given “high priority” by both industry and regulators as it "is clearly one of the main impacts on the environment and needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency". Recommendation 30 noted SEPA's proposals to develop a new regulatory framework for managing the waste input into the marine environment from fish farm cages and called on SEPA to keep it updated on progress.

In their response to the REC Committee report, the then Cabinet Secretaries referred to SEPA’s consultation on a strengthened regulatory framework for marine pen fish farming. In its response to the REC Committee report, SEPA provided further information about the proposals for its new regulatory framework, including "tighter environmental standards for organic wastes; greatly enhanced modelling requirements; much more environmental monitoring by farm operators and by us; and independent accreditation of the monitoring undertaken by operators". In addition, SEPA said the framework would allow "a more comprehensive approach to ensuring fish farm operators comply with the requirements of the new framework, including by using our wide range of enforcement powers and our new national enforcement team".

SEPA's revised regulatory framework for discharges from marine pen fish farms was published in 2019. The framework document states that:

to protect the marine environment, waste releases, and hence farm sizes and medicine usages, have to be appropriately matched to the sea’s capacity to disperse and assimilate wastes. As environmental regulator, it is our role to make sure this is the case.

The revised framework also committed SEPA to increasing its surveying of the seabed around marine pens to audit "for potential cumulative effects on the wider marine environment".

In her 2023 update, the Cabinet Secretary referred to SEPA's revised regulatory framework for discharges as setting a tighter standard for organic waste deposits and more accurate modelling. She also referred to SEPA's plans to develop the regulatory framework to include nutrient discharges in its screening modelling and a review of its regulatory approach to bath medicines.

Committee consideration

The Committee discussed issues around discharges from marine pen fish farms with witnesses. Specifically, the Committee considered whether there is now a better understanding of the environmental impacts of these discharges, and whether recommendations 29 and 30 have been implemented.

SEPA told the Committee the revised framework “provides significantly greater information, which enables us to speak with confidence about the impacts of the industry on the environment”. SEPA went on to explain that "the sampling exercises that are required now are significantly more comprehensive than what was in place for the industry at the point that the REC Committee's inquiry was undertaken”. SEPA said currently 65% of farms were subject to the licensing requirements in the revised framework and the rest would be transferred over by the end of the year.

Salmon Scotland told the Committee the discharge framework has provided "a much-improved understanding of our actual impacts on the environment" and that knowledge of the seabed has "changed dramatically since 2018 and the earlier report". Salmon Scotland also highlighted a number of projects it is partnering with SEPA and academic researchers to assess benthic biodiversity around fish farms.

Dr Reinardy agreed that the understanding of the benthic effects of discharges from farms "has been a major area of development and research" and that there have been "real developments" in the monitoring of sediments and waste deposits so that "we do have some good processes in place". She added, however, that “huge areas need further investment to understand them better and develop them more”.

Academics highlighted the impact on research from the lack of dedicated research pens in Scotland. Professor MacKenzie described this as a “huge gap” in Scotland's aquaculture infrastructure which has placed a number of restrictions on how research could be conducted. He noted that scientists are limited in the variety of sites and environmental conditions in which they can carry out research work, which can “make it very difficult to come to a scientific consensus”.

Concerns were raised by some environmental stakeholders that SEPA does not have sufficient resources to process and analyse data from its seabed surveys and that this compromises SEPA's monitoring and enforcement capabilities. The Coastal Communities Network told the Committee that:

At present, out of 210 farms, SEPA has 72 submitted seabed survey results, mostly from 2023, that have not been assessed, and some of those farms have been restocked. SEPA does not even have the capacity to assess those results, so providing it with more information is not really helping. It is not able to do its job properly.

The Committee heard concerns during its visit to the Scottish Association for Marine Science about gaps in SEPA's skills and resources when it came to analysing seabed samples.

In response to questions about the timeframe for analysing seabed survey samples, SEPA accepted it "would always like to be faster in turning data around and providing it to the public in a transparent manner" but explained that surveys take this long to analyse "because it is a very manual process". A Marine Directorate official told the Committee about a project to examine the deployment of 'environmental DNA' monitoring which would "not only speed up the process [of analysing seabed information] but also significantly reduce the costs".

During her evidence to Committee, the Cabinet Secretary referred to the significantly strengthened predictive modelling capabilities which are part of the new discharge framework. In addition, she highlighted that SEPA is working with operators to trial new innovative waste collection and removal systems, underpinned by a new charging regime to incentivise movement towards new technologies.

The Committee welcomes the introduction of the new discharge regulatory framework which sets a tighter standard for organic waste deposits and more accurate modelling. In addition, the Committee notes the view of industry and academics that there is now an improved monitoring and understanding of discharges from fish farms on the seabed. The Committee is concerned, however, that there remain uncertainties and knowledge gaps in understanding the environmental impact of waste discharges from salmon farms. The Committee is also concerned that current timescales for analysing seabed samples to assess regulatory compliance are too slow.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government and SEPA have made some progress in implementing actions in response to the REC Committee recommendations. The Committee agrees, however, that momentum should not be lost and that more could be done to understand and to minimise the impact of discharges. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government continue to support monitoring, data collection and research to improve the understanding and assessment of the impact of discharges on the marine environment. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government prioritise supporting SEPA in the development of techniques to accelerate the analysis of seabed survey samples as a matter of urgency and ensures SEPA has sufficient expertise and capacity to analyse seabed samples.

The Committee notes the REC Committee recommendation 57 which strongly endorsed the ECCLR Committee’s view on the need for more research to address significant gaps in knowledge, data, analysis and monitoring around the adverse risk the sector poses to the environment. The Committee notes evidence from researchers regarding the absence of dedicated research pens in Scotland which limits researchers’ ability to develop scientific consensus. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government work with industry and academia to establish dedicated research pens. The Committee also recommends that industry should contribute to the cost of financing this infrastructure.

Medicine use (recommendations 31 and 32)

Background

Salmon producers use medicines as part of their husbandry practices to treat fish health and welfare problems such as sea lice and disease. Medicines are licensed by SEPA and administered using a range of methods, such as additives to feed, injection or as bath treatments.

The ECCLR Committee reported that “there appear to be very significant data and analysis gaps relating to the discharge of medicines and chemicals into the environment, including analysis of cumulative or additive effects”. The ECCLR Committee went on to report that, as a result of these data and analysis gaps, it was "extremely concerned that SEPA may, in the past, or may currently, be permitting the discharge of priority substances and potentially damaging substances". This view was endorsed by the REC Committee report which recommended that any data and analysis gaps “should be addressed by both the industry and regulators" (recommendation 31).

The REC Committee report noted “with concern” the conclusion of SEPA research in 2018, which concluded that medicine from Scottish salmon farms “is significantly impacting local marine environments”. Recommendation 32 went on to welcome SEPA's application to the UK Technical Advisory Group (UK TAG) to consider whether a new environmental quality standard for the maximum concentration of emamectin benzoate – a medicated feed widely used by fish farms to control sea lice – in water was necessary. The REC Committee also recommended SEPA and the Scottish Government "consider the environmental impact of other medicines by the industry".

The Scottish Government committed, in response to the REC Committee report, to bringing forward changes to legislation in order to provide SEPA with responsibility for discharges of medicines from wellboats, which it said would create a more simplified and integrated regulatory framework for controlling waste and medicine discharges. This was actioned by the guidance, Wellboat treatment chemical residues – discharge to the water environment: transfer of responsibility, issued in October 2020.