Pre-budget scrutiny 2021-22

Introduction

The Committee’s primary focus in its pre-budget scrutiny this year is inevitably the impact of COVID-19 on the public finances and the operation of the fiscal framework. The Committee has carried out work in this area throughout the year and this pre-budget report provides a cumulative summary of our findings and recommendations.

The Committee has also continued to monitor the operation of the fiscal framework more generally and, in particular, the reconciliation of outturn data for the devolved taxes with forecasts and the impact on the Scottish Budget.

A number of non-COVID-19 related issues where raised in evidence and the Committee will seek to cover some of these in our report on Budget 2021-22 including replacement EU funding.

The Committee thanks all those who have provided written and oral evidence throughout the year to support our pre-budget scrutiny. We also thank our Budget adviser.

The Scale of the Economic Impact of COVID-19 and the UK Government’s Fiscal Response

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in its economic and fiscal outlook published alongside the UK Government one year spending review states that the UK economic growth is expected to fall by 11% in 2020 which is the largest fall in over 300 years.i They state that COVID-19 has “exacted a heavy and mounting toll on the public finances” with tax receipts “expected to be £57 billion lower, and spending £281 billion higher, than last year.”1 UK Government borrowing is expected to reach nearly £400 billion this year (19% of GDP) compared to the OBR’s forecast in March of £50 billion. This is the highest deficit since 1944-45 and by far the highest outside of wartime.

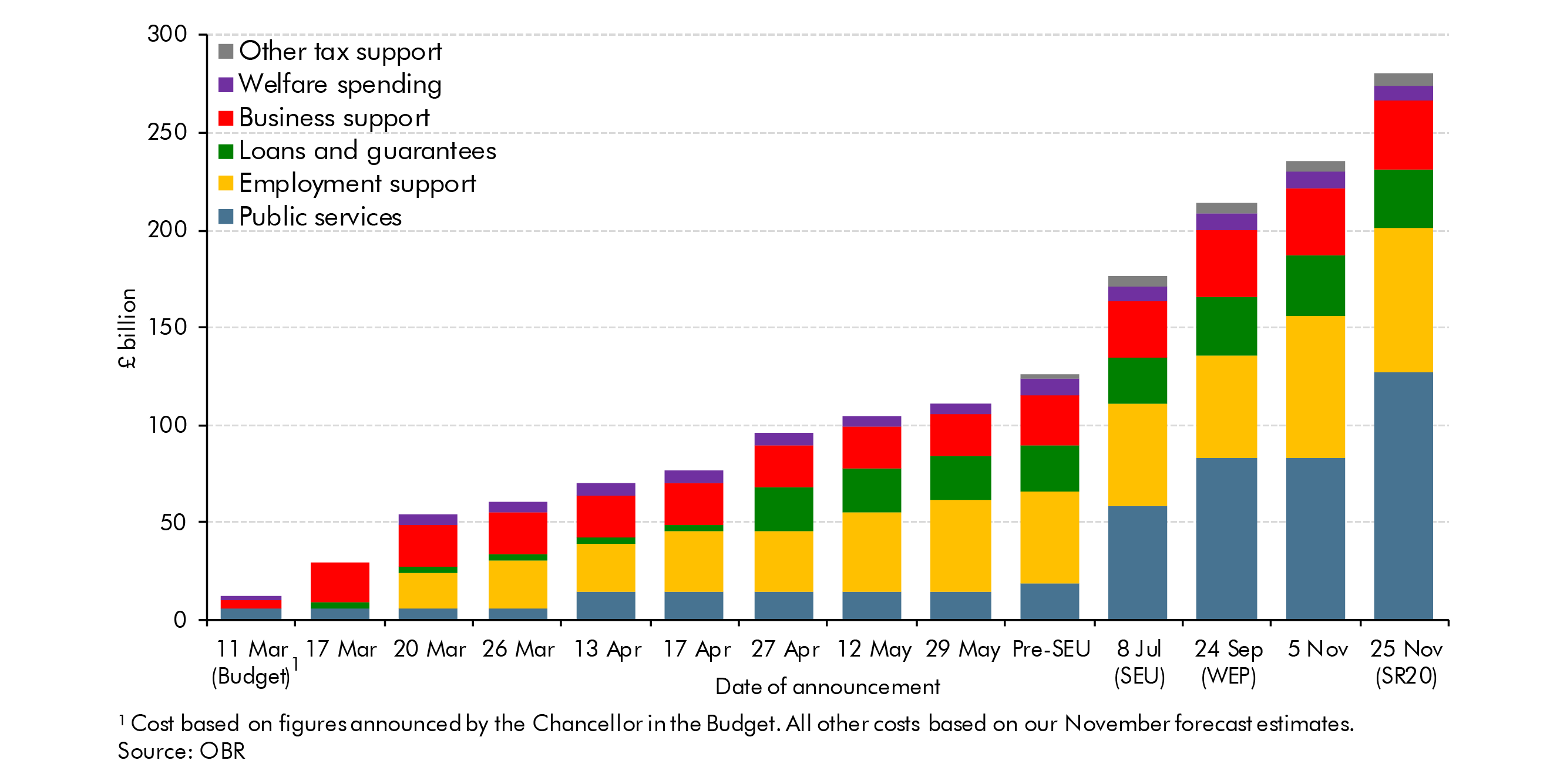

The OBR show that “year-on-year borrowing increases by £337 billion, of which £280 billion is down to virus-related support measures”1 which means that the “pandemic has driven public sector net borrowing to levels not seen since the two world wars.”1 The support measure include an additional £127 billion of funding for public services, £73 billion for employment and income support measures and £66 billion for business support measures. However, our Adviser points out that £25 billion of the £127 billion of funding for public services is actually a contingency reserve. The extent of these measures is show in Chart 1 below.

Chart 1: The evolving cost of the coronavirus policy response in 2020-21  OBR

OBR

Economic Outlook

The OBR points out that the “economic outlook remains highly uncertain and depends upon the future path of the virus, the stringency of public health restrictions, the timing and effectiveness of vaccines, and the reactions of households and businesses to all of these. It also depends on the outcome of the continuing Brexit negotiations.”1 Given this uncertainty the OBR have provided forecasts based on three different scenarios: upside, downside and central.

The central forecast is based on the following:

a higher infection rate at the end of the lockdown and a less effective Test, Trace and Isolate (TTI) system necessitate keeping a more stringent set of public health restrictions in place over the winter;

these may vary regionally and temporally but are broadly the same as remaining at the equivalent of England’s pre-lockdown Tier 3 until the spring;

the arrival of warmer weather then allows an easing of the restrictions;

an effective vaccine becomes widely available in the latter half of the year, permitting a gradual return to more normal life, though at a slower pace than in our upside scenario;

there is also a lasting adverse impact of the pandemic on the economy.

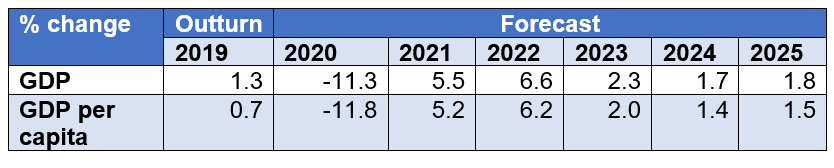

Based on this scenario the OBR’s economic growth forecast is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: UK GDP Growth  OBR

OBR

Fiscal Outlook

The OBR is forecasting that tax receipts “bounce back in 2021-22 as the economy reopens, activity normalises, and earnings and profits recover.” Expenditure levels for 2021-22 fall dramatically “as the temporary increase in departmental spending and support to firms and households wanes” but still amounts to £55 billion of which £21 billion is a contingency reserve. As a consequence of the recovery in tax receipts and lower expenditure, borrowing is expected to fall rapidly in 2021-22.

The fiscal outlook is also contingent on the outcome of negotiations concerning our future trading relationship with the EU and the OBR forecasts that a no deal scenario would “add a further £12 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) to borrowing relative to our central forecast in 2021-22.”

The Committee recognises that these figures demonstrate the sheer magnitude of the crisis which the country is living through and that the economic and fiscal outlook remain highly uncertain. The Committee also recognises and welcomes that the Fiscal Framework has operated as it should in protecting the Scottish Budget from a UK-wide economic shock. But as discussed in this report the trade off is that this also limits the flexibility of the devolved governments to develop a distinctive policy response to COVID-19 especially where the pandemic follows a different path.

This is because the UK Government uses its borrowing powers to fund its own policy response. Scotland benefits from this borrowing both if it is used to fund UK-wide measures such as the furlough scheme, or if it is used to fund England-only measures such as business rates reliefs, in which case the Scottish Government receives Barnett consequentials (and can choose how to spend this, including on its own business rates relief policy).

But if the UK Government chooses not to continue this policy or to reduce the level of relief then the Scottish Government will receive less funding. Given the limited fiscal levers which the Scottish Government has available within the Fiscal Framework the Committee recognises that it would be very challenging for the Cabinet Secretary to continue with policies like business rates relief, in its current form, without Barnett consequentials.

A key question for the Committee in this report is therefore whether the current Fiscal Framework is appropriate, especially in an emergency situation. In particular, whether the balance between protection against UK wide shocks and the Scottish Government’s ability to respond to specific circumstances and policy priorities in Scotland is calibrated correctly.

Within that context the huge challenge for both the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament in agreeing next year’s Budget is to ensure that the right choices are made in supporting economic recovery while continuing to deal with the impact of the health crisis. The Committee’s view is that given we are in a national crisis that the public will expect the Parliament and the Government to work together to meet this challenge.

Impact of Covid-19 on the Scottish Budget

As well as the whole of the UK benefiting from the UK-wide fiscal response to COVID-19 the Scottish Government’s Budget has also substantially increased as a consequence of Barnett consequentials which result from decisions made by the UK Government to spend money in devolved areas, such as health and local government. Where the UK Government spends money in these areas, the Scottish Government receives a population-based share which it can spend as it chooses.

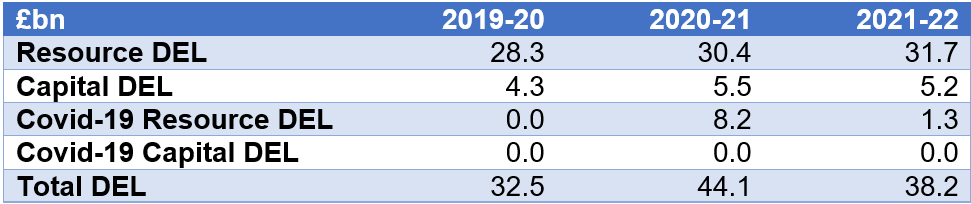

Following the decision of HM Treasury to provide a funding guarantee for Barnett consequentials for 2020-21, and the publication of the UK Spending Review for 2021-22 the impact of COVID-19 on the Scottish Budget is clearer. This is shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2: The Scottish Budget  UK Treasury, Spending Review 2020

UK Treasury, Spending Review 2020

The UK Spending Review sets out the HM Treasury Spending limits for the Scottish budget for 2021-22 as follows:

Resource spending is set to increase by over £1 billion from £30.4 billion to £31.7 billion in 2021-22.

Capital spending is set to fall from £5.5 billion in 2020-21 to £5.2 billion in 2021-22.

COVID-19 related funding is set at £1.3 billion in 2021-22, compared with the guaranteed minimum amount of £8.2 billion in 2020-21.

The Covid-19 related Barnett resource consequentials are non-recurring funding for 2021-22 only. On a departmental basis the largest element £719m relates to Health and social care. Within this £204m relates to testing, £208m relates to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and £291m relates to NHS recovery. Other significant areas of additional funding are related to:

Local Government - £289m

Transport (entirely rail related) - £200m

Education - £38m

HM Treasury have indicated that this is the initial estimate of Covid-19 consequentials for Scotland based on a Barnett share of £31 billion of the Chancellor’s total £55 billion Covid-19 funding announcement for 2021-22. The balance of £21 billion is being held in reserve against possible future costs including additional UK wide vaccination and testing costs.

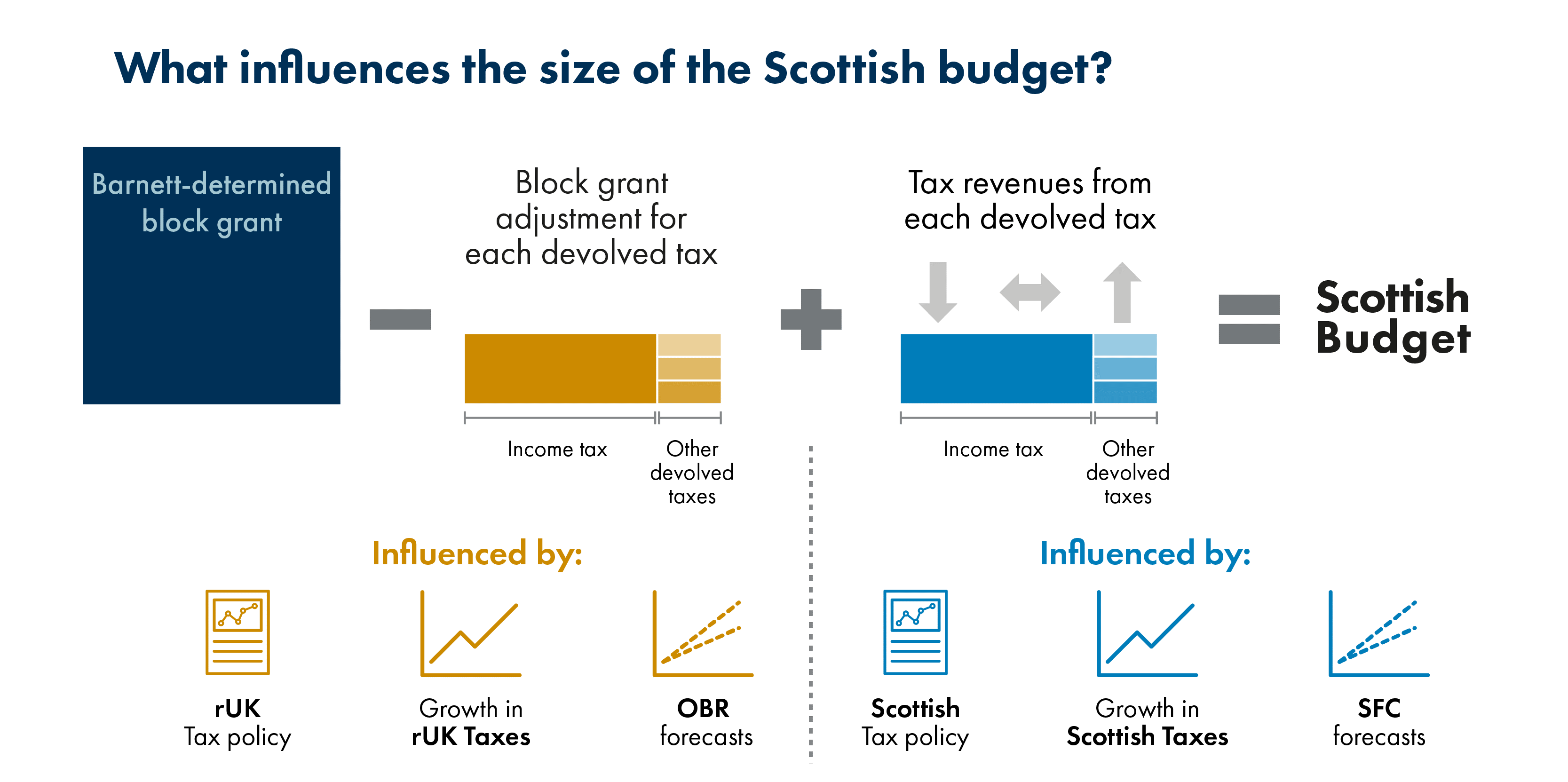

The Committee also notes, however, that the HM Treasury spending limit is not the final Scottish spending envelope for next year. The size of the Scottish Budget is also dependent on the tax policies of both the UK and Scottish Government where these are devolved and the impact of the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) and OBR tax revenue forecasts. This is shown in Figure 1.

Our Adviser points out that while the UK Spending Review has provided a guide to initial plans these may be revised between now and the start of the next financial year, depending on the path of the pandemic. Given the continuing uncertainty it is also likely that the UK Budget will require to be developed/ updated throughout 2021-22 in a similar way to this year. As noted above the UK Government has included a reserve of £21 billion in its Spending Review for pandemic related expenditure in 2021-22. This means that additional Barnett consequentials could flow to the Scottish Government if this reserve is used. It could also be topped up meaning even further consequentials.

On the other hand HM Treasury have not provided a funding guarantee for the COVID-19 related consequentials in 2021-22. This could mean that if the allocated funding is not spent in full then the Scottish Government would not receive all the consequentials which they have planned for.

A further challenge is that UK tax policy will also not be known when the Parliament is asked to agree the Scottish Budget 2021-22. While it is unlikely that there will be significant changes to income tax policy in the UK Budget in March there is the possibility of changes to property tax. On 8 July 2020, the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced a temporary stamp duty holiday that cut the rate of stamp duty to zero per cent for all properties £500,000 or under until 31 March 2021.

Following the Chancellor’s announcement, the Scottish Government introduced an increase in the nil Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) threshold from £145,000 to £250,000 on 15 July 2020. This temporary change will also be in place until 31st March 2021. A risk for the Scottish Government is that it will need to set its Budget including the rates and bands for LBTT without knowing the rates and bands for stamp duty in 2021-22. For example, if the Scottish Government wanted to continue with the nil rate threshold of £250,000 but the UK ended the temporary stamp duty holiday as planned then this would result in a reduction to the Scottish Budget.

Responding to the UK Spending Review the Cabinet Secretary stated that although it “provides some important information that will help us in setting our own budget, it raises almost as many questions as it answers.” She added that it is “not a budget, and without clarity on income tax and non-domestic rates we will be taking a step in the dark, with huge financial implications for Scotland.”

The Committee welcomes the funding guarantee provided by HM Treasury for Barnett consequentials in 2020-21 and recognises that this has provided much more certainty for the Scottish Government in managing its response to COVID-19.

However, the on-going uncertainty and volatility arising from COVID-19 and the on-going Brexit negotiations remains a highly challenging environment for the Cabinet Secretary to formulate her budget proposals for next year. This is evident from the level of contingency funding which the UK Chancellor has allocated to deal with the pandemic.

The Committee therefore recommends that HM Treasury gives a commitment that if the fiscal position continues to rapidly evolve in 2021-22 that a similar funding guarantee is provided to the devolved governments for COVID-19 related Barnett consequentials.

The Committee notes that the Scottish Budget will benefit from Barnett consequentials if this contingency funding is used. However, the Committee recognises that the Cabinet Secretary is likely to have much less room for contingency funding within the Scottish Budget to pursue a different policy response to the UK Government depending on how the crisis evolves in Scotland. But she does have the option to increase the Scotland Reserve which she could then draw down in-year if needed for COVID-19 related expenditure.

The Committee noted in its report on Budget 2020-21 that there will always be political pressure to allocate all available resources. But both the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament need to consider that, given the current crisis, it may be prudent to allocate some funding to the Scotland Reserve while recognising the annual drawdown limit of £250 million for resource spending. This could provide the Scottish Government with some flexibility to prioritise funding in certain areas later in the year when the path of the pandemic may be clearer.

Budget 2020-21 In-Year Revisions

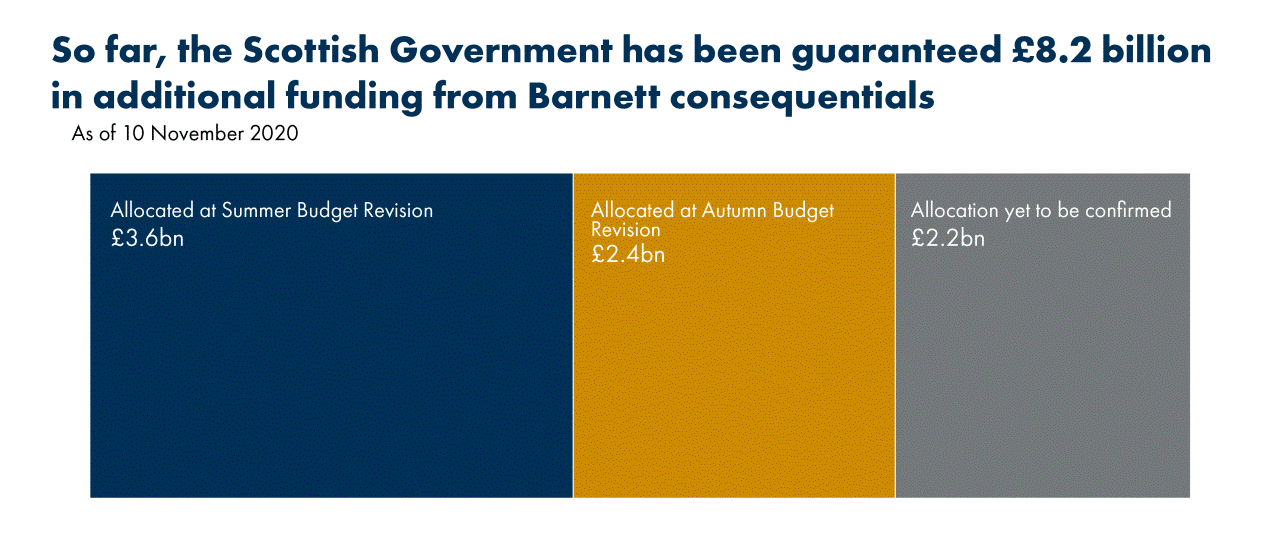

A total of £8.2 billion from Barnett consequentials has been guaranteed by HM Treasury for 2020-21 as shown in Figure 2.

During the early stages of the pandemic during which the UK Government’s budgetary response to the crisis evolved rapidly, it became apparent that the operation of the Barnett formula was impacting on the ability of the devolved governments to plan their own budgetary response. In response to these concerns, HM Treasury agreed to provide greater certainty over budget planning by providing an “unprecedented guarantee of additional in-year funding.”

The initial funding guarantee at the end of July was £6.5 billion. HM treasury also provided a commitment that the guarantee could only be revised upward. Further support measures announced by the UK Government on 9 October 2020 resulted in the funding guarantee for the Scottish Government being increased to £7.2 billion. The guarantee was then increased by a further £1 billion at the beginning of November to £8.2 billion as a result of an extension of the UK Government’s support measures.

Budget Revisions

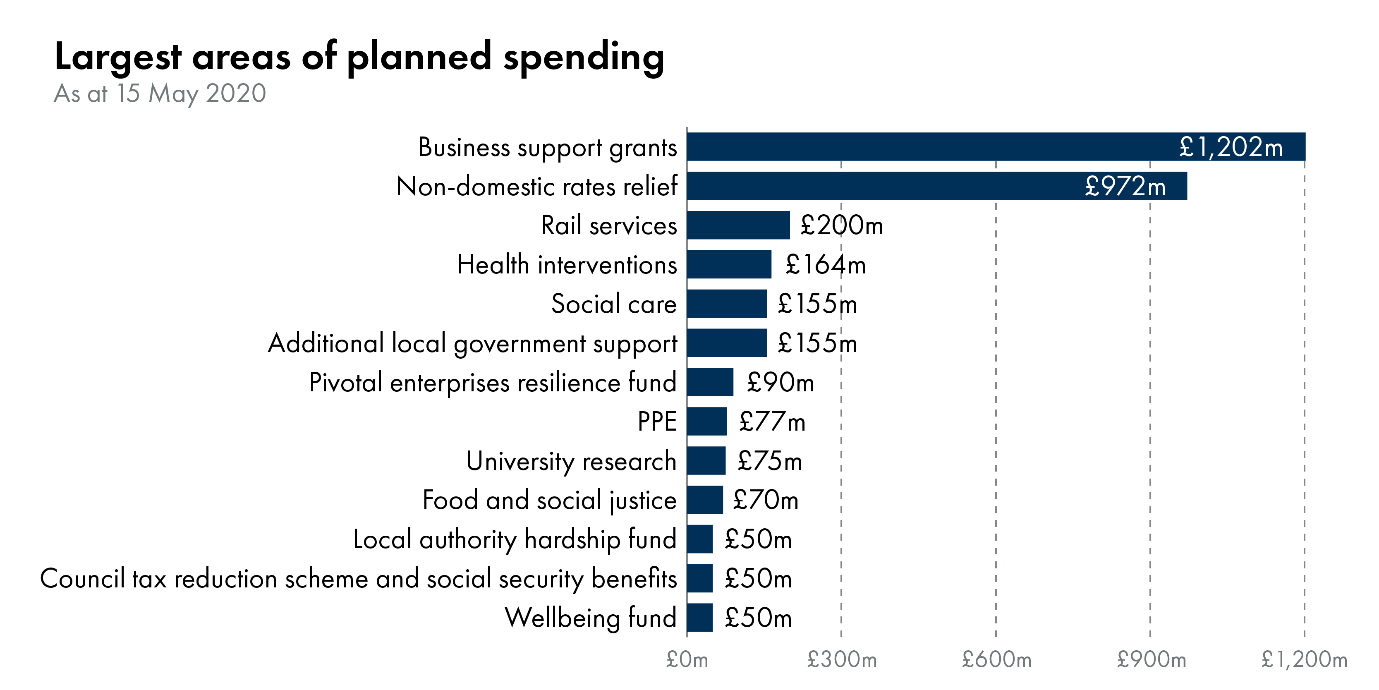

In-year revisions to the Budget including as a consequence of Barnett consequentials are normally agreed by the Parliament in the Spring and the Autumn. Given the unprecedented changes to Budget 2020/21 the Scottish Government published an additional Summer Budget Revision. This was published in May and allocated £3.581 billion of Barnett consequentials as shown in Chart 2 below.

Support to business accounted for £2.3 billion of the planned spending. This included the cost of non-domestic rates relief even though it is essentially income foregone. However, because the Scottish Government guarantees the combined General Resource Grant and Non-Domestic Rates Income figure to local government, there has been a corresponding increase in General Revenue Grant support from the Scottish Government to offset the reduced non-domestic rates income.

The Autumn Budget Revision published in September allocated a further £2.382 billion of Barnett consequentials. £1,839,9 billion was allocated to Health measures but in contrast to the Summer Budget Revision, a detailed breakdown of the planned use of this additional Health funding was not provided.

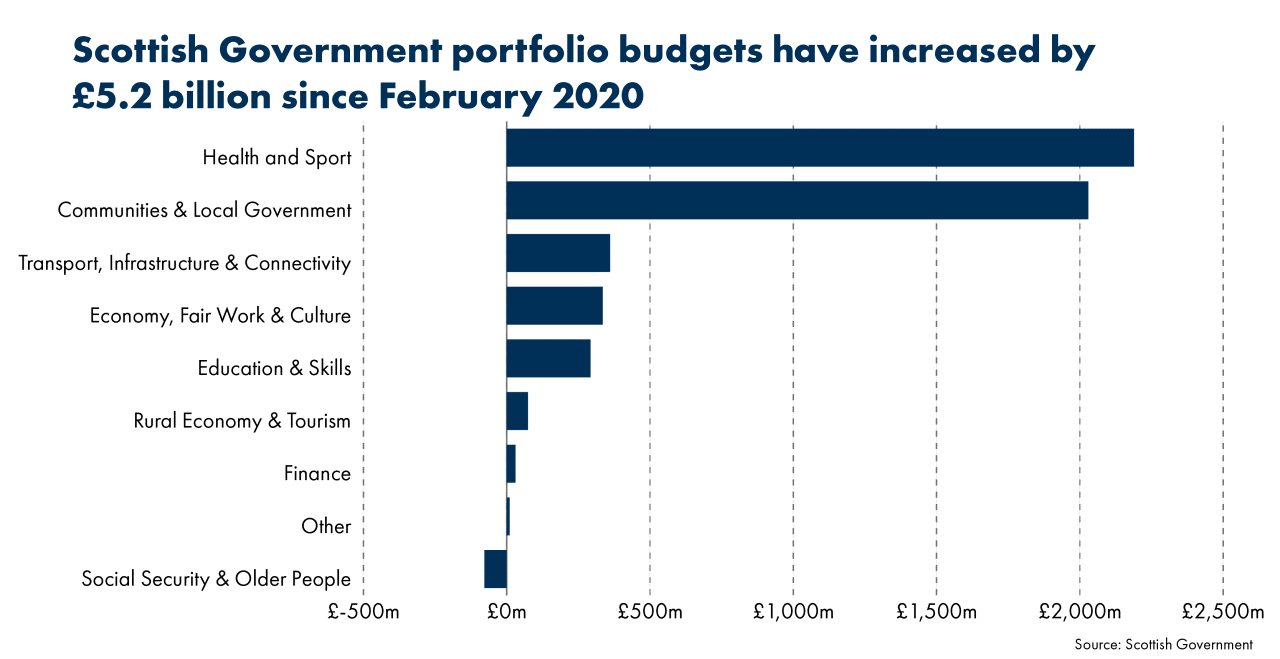

This means that at the time of writing a total of £5.963 billion has been allocated. Chart 3 below sets out how individual portfolio budgets have changed as a result of these two budget revisions.

In addition to the £5.2 billion allocated to individual portfolio budgets, the Scottish Government, as noted above has used nearly £1 billion of Barnett consequentials to compensate local authorities for the loss of non-domestic rates income. The budget revisions also allocate some other sources of funding (for example, non-Covid Barnett consequentials and Reserve drawdown), so the totals are slightly higher than the allocated consequentials. However, the vast majority of the funding allocated (over 95%) is Barnett consequentials resulting from the coronavirus response package.

Unallocated Consequentials

While around £6 billion of the Barnett consequentials have been allocated, a further £2.2 billion plus any further consequentials will not be formally allocated until the Spring Budget Revision, which is published in February. At the time of the Autumn Budget Revision £537m of Barnett consequentials remained unallocated.

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee in relation to the £537m that “the unallocated funding is currently being used to address the substantial current and anticipated Covid-19 funding requirements, which are already embedded in our budget position” and that, “as things stand, there is no headroom.”1 Given that and while welcoming the additional UK Government funding to date, the Cabinet Secretary has “continued to press the UK Government for additional fiscal flexibilities to support the Covid-19 response appropriately.”

The Cabinet Secretary provided the Committee with some details of where the remaining £537m will be allocated:

a minimum of £200 million as a bare minimum for maintaining transport networks, and the core costs are likely to increase over time;

Covid-19-related pressures and loss of income in education;

payments for those who are self-isolating or shielding.

The Committee also asked the Cabinet Secretary in November how much of the total Barnett consequentials which have yet to be allocated she considers would be prudent to hold in reserve. She responded that this “is a very good question, for two reasons.” First, the need to support economic recovery. The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that if the additional Barnett consequentials of £1.7 billion are “required to last from now until March, we need to ensure that we have funding available to invest in and support the recovery.”

Second, the rollout of a vaccine programme that will require funding. The Cabinet Secretary explained that a “huge amount and wide range of planning and guidance work is being conducted to assess the costs of providing the vaccination programme.” She stated that this “work on the cost implications is uncertain.”

The Committee also asked the Cabinet Secretary whether given some of the measures the Scottish Government have introduced to address the impact of the pandemic are demand led how she would be able to fund these if demand outstrips the money she has available. She responded that it is her job “to make sure that money does not run out and that we can continue to honour the commitments that we have made.”1

The Committee also sought clarity from the Cabinet Secretary regarding the process for allocating Barnett consequentials. In particular, at what point the relevant public bodies are notified of the allocation of additional funding and whether the Parliament should also be notified at the same time. She responded that “the spring budget revision is the point at which we can give perfect clarity. In advance of that, I can give reasonable certainty and clarity to various public bodies.”

Redeployment

As noted by Audit Scotland, in addition to using Barnett consequentials to fund its spending commitments, the Scottish Government identified in June 2020 a total of £855 million from the 2020/21 Budget that could be redeployed for Covid-19 related spending.1 Of this, £255 million was confirmed in the Summer Budget Revision, including:

Repurposing funding: £124 million of passenger subsidies for bus, rail and ferry operators repurposed to cover operators’ revenue losses due to reduced services and passenger numbers in lockdown.

Transferring funding: Due to anticipated reduced demand for energy efficiency projects, £105 million of Financial Transactions funding for domestic energy efficiency loans was transferred to fund emergency loans for housebuilders (£100 million) and private sector landlords (£5 million).

Delayed spending: Following a re-planning exercise (resulting in a delay to the introduction of planned changes to some disability assistance benefits), £26 million for the Social Security Programme (mainly for staffing costs) was redeployed to provide additional funding for the Unpaid Carers Allowance supplement and the Scottish Welfare Fund.

Audit Scotland also noted that £450m of the remaining £600m available for redeployment related to capital and financial transactions. They reported in August that £230m had been used to fund the “return to work” package to support construction, low carbon projects, digitisation and business support. However, as pointed out by the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) “only £50m of spending in the Autumn Budget Revision is explicitly badged as being part of the Return to Work programme.”2

A further £142m was reprioritised in the Autumn Budget Revision including an emerging underspend in Heat Networks of £50m and an emerging underspend in the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) of £50m. The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that in both cases “the underspend relates to capital that it has not been possible to spend because work was suspended during the lockdown period.”

The Cabinet Secretary also told us of two further examples of measures which the Scottish Government has funded in response to COVID-19. These are “the distinctive package of business support measures—such as the pivotal resilience fund and the hardship scheme—and the £350 million welfare and wellbeing fund.” She explained that “this spending was based on our own budget; it was not funded by additional consequentials—it was distinctive.”

The Committee welcomes the stated willingness of the Cabinet Secretary to provide detailed information within a fast-moving fiscal environment. The Committee would also welcome further information on COVID-related spending without diverting resources unnecessarily from managing the response to the pandemic.

However the Committee notes that significant spending commitments such as the £500 payment to NHS and care staff have been announced since the Cabinet Secretary gave evidence, and that no information has been provided to the Committee about the costing of this policy or the impact on the spending areas highlighted by the Cabinet Secretary in her evidence.

The Committee invites the Cabinet Secretary to provide details of all resource expenditure and capital expenditure which has been redeployed from the Budget agreed by the Parliament in March to deal with COVID-19. The Committee also asks the Cabinet Secretary to provide details of all resource and capital expenditure which has been identified as being available to be redeployed but remains uncommitted.

The Committee also invites the Cabinet Secretary to provide details of any increased COVID-19 related funding which she has committed and which remains uncommitted as a consequence of actual or assumed savings from demand-led programmes and from in-year revisions to the fully devolved taxes.

Transparency and Scrutiny

The Committee recognises that it’s never been more important that the Government is transparent about how the budget is being managed throughout the year, and that Parliament can scrutinise this. The Committee, therefore, welcomes the willingness of the Cabinet Secretary to provide additional information including the Summer Budget Revision and an update in December.

Even so and while recognising the enormity of the task faced by the Scottish Government, in managing the fiscal response to COVID-19, it has been challenging for the Committee to monitor and scrutinise the extent of the in-year revisions to Budget 2020-21. The scale of the challenge is highlighted by Audit Scotland who point out that “between 18 March and 31 July, the Scottish Government has announced over 90 spending and tax measures to help support business, public services and individuals during the pandemic.”1

As noted by SPICe, the “inevitably fast-changing nature of the coronavirus response package means that the normal fiscal scrutiny processes aren’t frequent enough to keep pace with the changes in the budget.”2 The resource budget has now increased by almost a quarter since it was agreed by the Parliament in March. As SPICe point out “this presents a challenge for effective scrutiny”.

While the guaranteed funding allows the Scottish Government to plan its own response package with greater certainty, parliamentary scrutiny of the additional funding is more challenging. This is because it is not possible to be certain about which UK Government announcements are generating consequentials and what sums are being allocated to Scotland as a result. As SPICe point out, “Barnett calculations are going on behind the scenes at HM Treasury and are unlikely to see the light of day until the next UK budget.”

This also makes it difficult to scrutinise whether the Scottish Government is fulfilling commitments it has made. For example, the Scottish Government has committed to passing on all health-related Barnett consequentials to the Scottish Government’s health budget. But as noted by SPICe, “it is not possible to identify how much of the £8.2 billion guarantee relates to UK government health spending.”

The Cabinet Secretary told us that there “has been significant difficulty in tracking the individual consequentials arising, particularly where initiatives are demand led.” She provided the example of demand-led self-isolating payments in England “which means that it is difficult for the UK Government to confirm what consequentials might arise.” This means that it is difficult for the Scottish Government to design “self-isolating payments, because they may or may not be covered by the consequentials that emerge.”3

The Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee in October that there “is on-going discussion between my officials and Treasury officials to get clarity on a reconciliation of all the announcements that have been made to date that generate consequentials and how they track against the funding guarantee.” The Cabinet Secretary subsequently told us on 18 November that by December we might have “a broad, high level reconciliation from the UK Government, but we are being advised that a more detailed reconciliation will probably not be available until January at the earliest.”

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary in October whether she would consider providing more detail to the Committee on how the remaining Barnett consequentials will be allocated prior to the Spring Budget Revision. She responded that she would give careful thought to what additional information could be provided but “with the heavy caveat that it would be a snapshot in time in the middle of a dynamic and fluid situation.” She subsequently told us on 18 November that she is “very keen to provide the committee with advance sight of as much information as possible in December, rather than waiting until the spring budget revision”4 but with the same caveat that it will be a snapshot in time.

The Committee notes, while recognising the highly fluid fiscal situation, that COVID-19 related spending announcements have been regularly made by the Scottish Government in the period between budget revisions. Audit Scotland published in August a snapshot of COVID-19 related spending commitments made by the Scottish Government after the Summer Budget Revision and up to the end of July. They noted that the Scottish Government “expects spending for announcements made since the Summer Budget Revision to be £571 million of day-to-day spending and £230 million of capital spending in 2020/21.”5

The Committee recognises that the budget revision process provides some transparency regarding in-year changes to Scottish Government spending. But as pointed out by the FAI—

“whilst the budget revisions show in broad terms how allocations to different portfolios have changed, they often provide funding information at a more aggregated level than is made in government policy announcements.” ; they also conflate Covid and non-Covid spending changes, and new funding with transfers of existing funding between portfolios. It can therefore be tricky to match up spending changes with specific policies.”6

The Committee asks the Scottish Government, given the challenge of reconciling the funding guarantee with UK Government policy announcements, how it is ensuring that all health related Barnett consequentials are being passed on to the health budget in Scotland.

The Committee recognises that it is not practical to set out how every individual addition to planned spending programmes has been funded in budget revision documents. We note that there may be a number of additional sources of funding which the Cabinet Secretary has collectively at her disposal for increased spending. However, the Committee believes that it is essential, especially in the current fast-moving fiscal environment, that all elements of the total funding available for in-year expenditure revisions are set out in the budget revision document.

This should include all assumptions which the Scottish Government has made in relation to future tax revenues and block grant consequentials which are available to allocate expenditure. For example, where in-year revisions to the devolved taxes or changes to UK tax policy in devolved areas have resulted in changes to the total amount of funding anticipated, this should be clearly set out.

Any assumptions about changes to previously anticipated cost of demand led expenditure (such as social security or business support grants) should also be given. These various elements should be provided in a table which shows the total available additional funding which the Government has at its disposal in the budget revision which can be read alongside the total expenditure figure.

The Committee welcomes the commitment by the Cabinet Secretary to provide information in December on additional budget allocations since the Autumn Budget Revision was published.

The Committee recommends that this position statement should include, without being overly onerous for officials, a snapshot to the end of November of all budget allocations arising from COVID-19 related spending announcements since the Autumn Budget Revision was published, alongside the movement in block grant and other funding.

It should also include the latest position in relation to take up for demand-led COVID-19 related measures including any underspends which have been anticipated to allow spending announcements.

Operation of the Fiscal Framework During a Crisis

As the Committee has highlighted in previous budget and pre-budget reports, the Scottish budget is exposed to broadly two types of budget risk through the Fiscal Framework in relation to the tax devolution:

The first is the risk that the tax base grows relatively more slowly than the equivalent income tax base in rUK. If this happens, then Scottish revenues are likely to be lower than the block grant adjustment. The implication of this is that the Scottish budget is worse off than it would have been had tax devolution not occurred;

The second is the risk of forecast error. This is the risk that a Scottish budget is based on a set of forecasts that turn out to have overestimated the level of funding available to the Scottish Government. If this happens, then a subsequent budget will need to address any shortfall.

A key question for the Committee is the extent to which the current health crisis has exacerbated both of these risks.

Differential Impact

The fiscal framework protects the Scottish Budget from a UK-wide economic shock such as that caused by COVID-19. This is because any fall in revenue from the devolved taxes is offset by the adjustment to the block grant as a consequence of any similar fall in revenue from the equivalent rUK taxes. However, there is a risk for the Scottish Budget if there is a differential impact on the Scottish economy relative to the rUK economy. For example, if the pandemic has a more negative impact on the Scottish economy compared to the rUK economy or if the Scottish economy recovers more slowly than in England. There is a risk that either or both of these scenarios could result in relatively lower tax revenues in Scotland compared to rUK and therefore a reduction in the size of the Budget. But at the same time there is also a possible upside scenario in which the Scottish economy is less badly impacted and/or recovers more quickly.

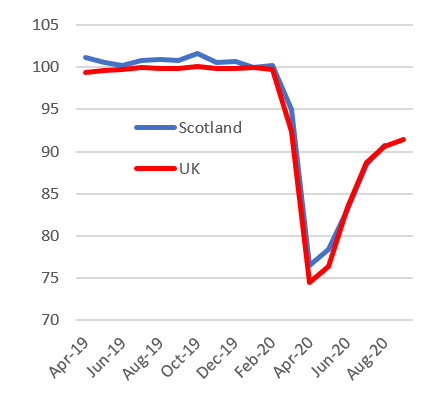

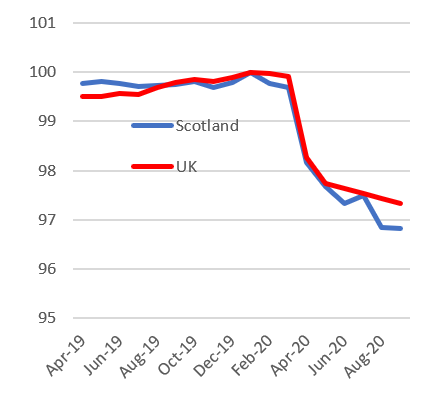

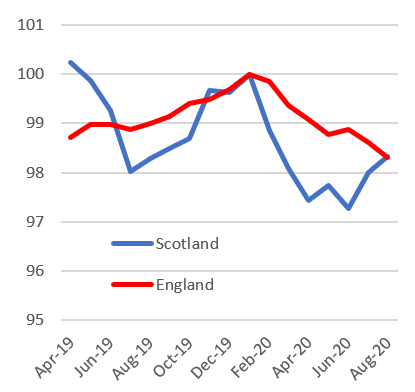

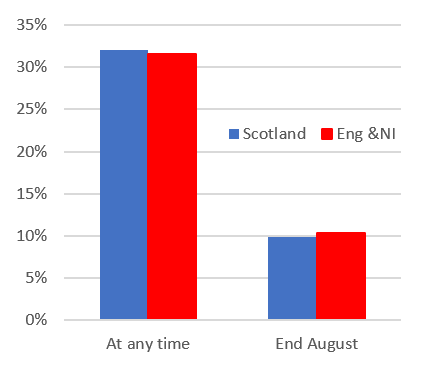

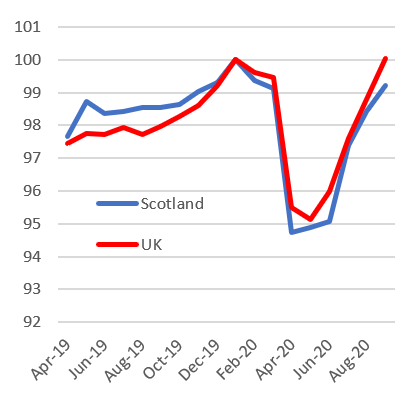

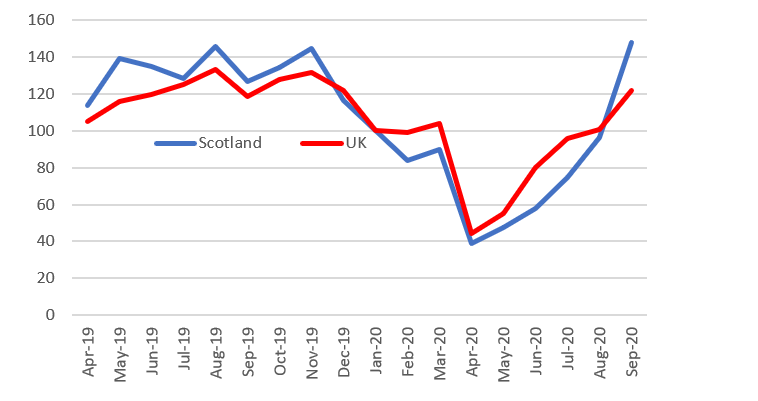

Our Adviser points out that this makes it worthwhile considering how the Scottish economy and revenues have evolved relative to the situation in England and Northern Ireland. Figures 3 to 9 illustrate relative performance for a number of economic indicators for Scotland and either England and Northern Ireland or the UK as a whole (which is a close proxy for England and Northern Ireland). (In all Figures except 4 and 7, Jan 2020 = 100).

Figure 3: Gross Domestic Product (GDP)  Scottish Government and ONS National Accounts

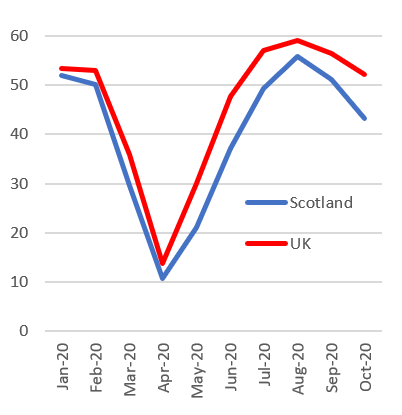

Scottish Government and ONS National AccountsFigure 4: Purchasing Managers Index  Markit Economics, Composite PMIs

Markit Economics, Composite PMIsFigure 5: Employees on Payroll  ONS, RTI payroll and earnings

ONS, RTI payroll and earningsFigure 6: Employment rate  ONS Labour Force Survey

ONS Labour Force SurveyFigure 7: Employees on furlough  HMRC, Job Retention Scheme Statistics

HMRC, Job Retention Scheme StatisticsFigure 8: Aggregate pay bill  ONS, RTI payroll and earnings

ONS, RTI payroll and earningsFigure 9: Residential property transactions  HMRC, Properties transacted for over £40k

HMRC, Properties transacted for over £40k

These figures present a mixed picture according to our Adviser, meaning it is difficult to provide an overall assessment of the extent to which Scottish revenues may change differentially this year:

GDP is estimated to have initially fallen by less than in the UK as a whole, and to have recovered by broadly the same extent by the end of August. On the other hand, the Scottish Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) – based on a survey of private sector businesses – has been consistently below the UK PMI this year, especially since May, suggesting a slower and weaker economic recovery;

Real time information (RTI) from HMRC collated by the ONS suggests that payrolls in Scotland fell by 3.2% between January and September, compared to 2.7% across the UK as a whole. Aggregate earnings (including furlough payments) subject to PAYE are estimated to have fallen by 1.8% in Scotland between April and September 2020, compared to the prior year, compared to 0.6% for the UK as a whole;

The Labour Force Survey also suggests a larger decline in Scotland relative to England – although this is within the margins of statistical uncertainty. The Furlough scheme data suggests a very slightly higher proportion of Scots workers have been furloughed at some point (32.0%) compared to England and Northern Ireland (31.5%) but that a slightly lower proportion were furloughed by the end of August (9.8% versus 10.3%);

Residential property transactions initially recovered more slowly but by September 2020 exceeded levels across the UK as a whole.

Our Adviser also points out that Scotland’s underlying economic and demographic structures mean that there are factors that may be expected to lead to both larger and smaller impacts on the Scottish economy and Scottish income tax revenues:

A slightly larger share of Scottish workers are in the accommodation and food services sector (7.5%) than in England (6.9%), which may be expected to lead to a larger negative impact on Scottish income tax revenues given the particular effects of the COVID-19 crisis on this sector;1

A larger share of Scottish workers are in the oil and gas sector and the associated supply chain than is the case in England, which may be expected to lead to a larger negative impact on Scottish income tax revenues given the effects of falls in oil and gas price on employment in the sector;

Conversely, a larger share of Scottish workers are in the public sector (21.2%) than is the case in England (15.8%).2 This would be expected to lead to a smaller negative impact on Scottish income tax revenues given public spending has been maintained (and indeed increased) during the crisis – supporting employment and earnings;

In addition, a slightly higher fraction of the taxpayer population of Scotland is over the state pension age (19.5%) than in England (19.2%) and the incomes of retirees is likely to be less affected by the COVID-19 crisis than those who were employees or self-employed (at least prior to the crisis). This may be expected to lead to a smaller negative impact, but the effect is likely to be only marginal.

Differences in economic and public health policies will also play a roll. Measures in the initial lockdown were more stringent in Scotland (for example in relation to construction) – and were relaxed more slowly. More recently, however, while the whole of England has been under a second lockdown since 6 November 2020, Scotland’s 5 tier system has meant all or parts of Scotland have been subject to less stringent rules.

Our Adviser’s view is that overall the larger public sector in Scotland suggests that all else equal we would have expected a smaller impact on tax revenues in Scotland. However, the larger falls in employment and aggregate earnings captured by RTI suggest income tax at least may fall by more – with the role of the oil and gas sectors and differences in policies being possible explanations.

While not having a direct impact on the size of the Scottish Budget the OBR’s devolved taxes forecasts provide some insight into the risk of a differential impact to the Scottish economy and income tax revenues relative to rUK. Our Adviser points out that the OBR forecasts don't build in any differential economic impact of COVID-19. In other words they assume that the fiscal and economic impact will be similar across the UK.

The SFC’s view of any possible divergence is that “the economic impact has been relatively similar” and “we do not see any significant difference at the aggregate level so far.” But they also recognise “it is still early” and they “have significantly increased our use of real-time data to spot differential impacts.”3

Forecast Error

The Committee has consistently highlighted the budgetary risks arising from the operation of the fiscal framework. In particular, the risks attached to setting a budget based on two sets of forecasts with one made by the SFC and the other made by the OBR and subsequently reconciling these forecasts with outturn figures. A key question for the Committee is the extent to which the current health crisis has exacerbated this risk.

One of the risks which the Committee has previously considered is the impact of SFC and OBR forecasts going in the opposite direction rather than cancelling each other out. For example, if the SFC was too optimistic and the OBR too pessimistic then this would result in a much higher reconciliation figure than if they were respectively too optimistic or too pessimistic.

The SFC told us that their forecasts for 2020-21 “will be very wrong, because we did not factor in the pandemic” but they “are pretty sure that they will be in the same direction”1 as the OBR forecast error for the BGA. This essentially means that Budget 2020-21 is protected from the impact of COVID-19 as both the BGA and Scottish income tax receipts will be much lower than forecast. As noted above this is because the Fiscal Framework is designed to protect the Scottish Budget from a UK wide economic shock such as that caused by the pandemic.

A further potentially complicating factor is the timing of the respective forecasts during a period of considerable uncertainty. The SFC forecasts will benefit from being finalised after the end of the Brexit transition period when the future relationship with the EU should be clearer. They may also benefit from being after the Christmas period when the path of the health crisis and the vaccine programme may be clearer.

The question for the Committee is how this will impact on the Scottish Budget and subsequent reconciliation process. For example, the OBR’s central scenario assumes that an effective vaccine becomes widely available in the latter half of the year. But by the time the SFC publishes its forecasts at the end of January it may be apparent that an effective vaccine will be available much sooner. This could result in the SFC forecasts being much more optimistic than the OBR forecasts. This would be good news for the Cabinet Secretary in managing her Budget 2021/22 but potentially bad news for whoever is the Cabinet Secretary in 2024/25. This is because the more optimistic SFC forecasts would mean a larger Scottish Budget in 2021/22 but the more pessimistic OBR forecasts would mean a negative reconciliation payment is needed in 2024/25 when outturn figures for the BGA turn out to be higher.

The Committee notes that there a number of factors which could result in the pandemic having a differential impact on the Scottish economy relative to rUK:

impact on different sectors of the economy;

the strength and period of economic recovery;

the length and level of lockdown.

While the Committee notes that it is much too early to have any clarity on the extent of the risk of these potential differential impacts it would be helpful if the SFC can address the level of risk in its economic and fiscal forecasts.

With regards to forecast risk the Committee’s view is that the current levels of uncertainty and volatility could exacerbate the risks from forecast error. In particular, the rapidly evolving situation is likely to have an impact on the OBR and SFC forecasts given they are 2 months apart. This raises the question which the Committee has previously asked of whether the existing borrowing powers for forecast error are sufficient.

Additional Fiscal Flexibilities

The Committee has previously considered what additional fiscal flexibilities may be required to address the risks to the Scottish Budget arising from the operation of the Fiscal Framework. The further volatility and uncertainty arising from the impact of COVID-19 also raises the question of whether the Fiscal Framework provides sufficient fiscal levers for the Scottish Government to respond to the crisis.

The Cabinet Secretary told us in June that the financial impact of COVID-19 “exposes us to additional financial risks that the current fiscal framework arrangements do not allow us to manage effectively.” She added that it “is clear that the fiscal framework was not designed for a pandemic or an economic crisis on such a scale.”1

The Cabinet Secretary has written to both the Chief Secretary to the Treasury (CST) and the Chancellor requesting the following fiscal flexibilities:

The ability to offset capital underspend against resource expenditure;

Flexibility over resource borrowing;

Greater flexibility in relation to the Scotland Reserve for capital.

She explained in a letter to the Committee in July that “these represented minimum short-term flexibilities that are needed to address the exceptional economic and fiscal challenges brought about by COVID-19.”2 Since then HM Treasury have provided an upfront guarantee of Barnett consequentials to support the Coronavirus recovery but it has not, so far, agreed the other fiscal flexibilities requested by the Scottish Government.

The CST wrote to the Committee in September explaining that the unprecedented guarantee of additional in-year funding alongside existing financial flexibilities “provides the Scottish Government with the necessary funding certainty to deliver its response to COVID-19 this year” but that he would “keep discussing the Scottish Government’s financial position with the Cabinet Secretary for Finance throughout the year.”3

In response to the other fiscal flexibilities requested by the Scottish Government the CST explained that he is “reluctant to move away from the agreed arrangements” in advance of the review of the Fiscal Framework. He added, however, that as demonstrated by the funding guarantee, he is “willing to consider the evidence” and is “keen to have an ongoing dialogue” with the Cabinet Secretary. To support that on-going dialogue the Committee has continued as part of its pre-budget scrutiny to examine the options for further fiscal flexibilities and these are discussed below.

Capital to Resource Switches

Under HM Treasury’s fiscal rules the Scottish Government is able to switch funding from its resource budget to its capital budget but it is unable to switch funding from capital to resource. The Committee recognises that given the impact of COVID-19 on construction work a lot of the capital budget this year will not be spent.

The Cabinet Secretary told us in June that it is probable that in the current financial year “a whole quarter of construction work will have been suspended” while on the other hand, “we are facing the most challenging pressures on our revenue budget.”1In a letter to the Committee in July she explained that she “would welcome flexibility to utilise any further emerging underspend” on capital budgets to fund resource pressures and had pressed that point at the Finance Ministers Quadrilateral meeting on 26 June.2 She pointed out that the “flexibility to utilise up to 10% on these budgets - £500 million - to offset resource pressures would help the Scottish Government to manage the COVID-19 response.”

Resource Borrowing and Reserve Powers

The issue of whether the resource borrowing powers within the Fiscal Framework are sufficient predates COVID-19. Resource borrowing can only be undertaken for the following reasons:

For in-year cash management, with an annual limit of £500m;

For forecast errors in relation to devolved and assigned taxes and social security expenditure, with an annual limit of £300m (increasing to £600m in the event of Scotland-specific economic shock).

The Scottish Government also has the ability to smooth expenditure, manage tax volatility and determine the timing of expenditure through building up funds in, and drawing down funds from, the Scotland Reserve. The Reserve is capped in aggregate at £700m and is split between resource and capital. Annual drawdowns are limited to £250m for resource, and £100m for capital. There are no annual limits for payments into the Scotland Reserve.

The Committee has previously examined whether the level of volatility and uncertainty in the operation of the Fiscal Framework is greater than anticipated and therefore whether the borrowing and reserve powers are sufficient to manage that volatility. In a joint letter to the CST, the Committee, the Social Security Committee and the Cabinet Secretary recommended that the review of the Fiscal Framework should—

“consider the limits and caps on the resource borrowing powers and reserve to ensure they are sufficient to manage the volatility created by the Fiscal Framework.”1

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy and the public finances inevitably raises further questions about whether the Fiscal Framework is flexible enough to address the unprecedented levels of uncertainty and volatility. The joint letter to the CST therefore recommends that “the review includes an analysis of the lessons learned and considers what if any changes need to be made to deal with both the ongoing crisis and any future crises.”

In particular, whether changes to the Scottish Government’s borrowing powers may be appropriate given the following reasons:

The Fiscal Framework is behaving as it was intended to do, though there are some respects in which the Scottish government might seek to negotiate temporary alleviations from HM Treasury;

The rules on borrowing were not designed for the current crisis including the need to develop, cost and announce new measures very rapidly and the potential for each of the four nations of the UK to be affected by coronavirus in very different ways;

To address an immediate shortfall in receipts from Land and Buildings Transaction Tax which is collected by Revenue Scotland and which will be much lower than the SFC forecasts due to the crisis;

To address a differential public finance impact in Scotland compared to rest of the UK arising a different policy response in Scotland or a differential impact of the pandemic on the Scottish economy or a combination of both;

The existing provisions within the Fiscal Framework to address a Scotland specific economic shock were not designed to deal with a crisis such as COVID19.

The joint letter to the CST states that there “continues to be a pressing need to reach agreement regarding the debate over additional flexibilities and powers in the short term so that each of the devolved governments can more effectively manage their respective budgetary response to COVID-19.”2

At the same time the Committee recognises that both the Scottish economy and the Scottish Budget have significantly benefited from the unprecedented levels of government borrowing by the UK Government. This led one of our witnesses to conclude that leaping to the idea of additional borrowing powers for the Scottish Government as the answer is premature.

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary in October whether there had been any progress in discussions with HM Treasury in relation to increasing the Scottish Government’s fiscal powers. She responded that there “has been no progress on the fiscal flexibilities, of which two are the repurposing of capital and dealing with the borrowing limits.” She pointed out that this would “not cost the UK Government a penny and it would enable us to be more flexible with the funding and budget that we have.” She told us that most governments “would not reduce their spending power to deal with forecasting errors; they would ensure that there is borrowing cover to smooth the curve of that error.”3

The Cabinet Secretary also told us in November she remains very disappointed “that there was no agreement provisionally and temporarily to give us additional powers during the pandemic.” Looking ahead to the fiscal framework review, in her view “it is essential that we build on what we have learned from the operation of the framework to date and take account of what the pandemic has revealed about its inadequacies.”4

Audit Scotland told us that “the levels of volatility and uncertainty that we are experiencing as we look towards 2021-22 and, importantly, in-year, as things have adjusted throughout the year, are far ahead of what anybody envisaged when the framework was established.” In their view it “is important that all those things play in to the review.”4

The Cabinet Secretary told us that the requirement to balance the Budget annually means that the Cabinet Secretary has “to take a very prudent approach to setting our budget and that is very difficult when we are wanting to make every penny go as far as possible to fund local government and the health service.” This is much more challenging than normal due to the lack of certainty regarding the UK Budget. The Cabinet Secretary points out that while she “will have provisional block grant adjustments in the spending review” it is unlikely that she “will have much, if any, UK Government commitment” and “will certainly have very little clarity on consequentials.”

The Committee notes that the borrowing powers in the Fiscal Framework were not designed to deal with situations like the COVID-19 crisis when there can be a need to develop, cost and announce new measures very rapidly and there is the potential for the nations of the UK to be affected by the COVID-19 crisis in significantly different ways.

The Committee recognises that this means that the devolved governments are very reliant on funding from the UK government in order to be able to fund additional policy measures. It also means that it is difficult for the devolved governments to pursue distinctive additional policy choices from the UK Government given the reliance on Barnett consequentials to fund these.

The COVID-19 crisis has therefore exposed one form of asymmetry in the UK’s fiscal architecture: that the UK government, which is the government of both the UK and England, controls the overall fiscal stance – including the level of borrowing. There have been concerns that this has led to borrowing to support COVID-19 policies in England (such as the extension of the furlough scheme to coincide with the second national lockdown) but being unavailable to support COVID-19 policies in the rest of the UK (such as Wales’ “firebreak” lockdown).6 The Committee notes that reforming the devolved government’s fiscal framework to give them more scope to borrow would lessen this asymmetry.

Fiscal Flexibilities and Powers for Local Authorities

A key theme to emerge from our pre-budget scrutiny is the extent to which additional fiscal flexibilities and powers are needed for local authorities to respond to COVID-19 and whether existing flexibilities will be extended in 2021-22. The existing flexibilities have been funded almost wholly by Barnett consequentials arising from UK Government measures in England including:

Funding for business rates reliefs for the retail, hospitality and leisure (RHL) sectors and nurseries totals £11.2 billion – an increase from initial estimates of £10.2 billion in April.

Funding for business grants delivered by local government totals £15.1 billion, with £12.9 billion of this as a result of schemes announced at the start of the first lockdown (although only £11.7 billion had been allocated by the end of September) and £2.2 billion as a result of schemes announced alongside the second lockdown.

Funding for local government services (delivered from a range of departments, including MHCLG, DHSC, Transport, Education) totals £6.4 billion, with an estimated £1 billion of additional support via a compensation scheme for losses in sales, fees and changes income on top.

Business Rates Relief

On 18 March, the Scottish Government announced a significant package of support to business in response to COVID-19, including two new reliefs in 2020-21 for NDR:

1.6% rates relief for all properties across Scotland, effectively reversing the increase in the poundage from 1 April 2020 for one year;

100% rates relief for retail, hospitality and leisure sectors along with all airports from 1 April 2020 for one year.

The SFC published a policy costing for both of these reliefs in March. The 1.6% relief was costed at £51m while the 100% relief was costed at £824m resulting in a total costing of £875m.1 The SFC point out in their fiscal update in September that revenue “will be reduced further if businesses become bankrupt or go into liquidation and claim empty property relief, or if businesses that are struggling financially do not make payments.” The latest estimate to fund the estimated shortfall in income from NDR is £972m as set out in the Autumn Budget Revision.

COSLA also point out that “the financial risks to both the Scottish Government and Local Government will go beyond 2020/21.” In particular, the risk to the Scottish Government of significantly reduced NDR revenue “will present risks to the Local Government Settlement as well, given it forms a key part of the overall funding to Local Government.”2

The Cabinet Secretary told us that perhaps “the area of greatest debate right now is non-domestic rates and whether we might see an extension of the 100 per cent relief.” She pointed out that given “it will cost just short of £1 billion this year, an extension is prohibitively expensive for us if there is not an equivalent UK Government scheme that generates consequentials.” While she is keen to provide additional reliefs “that is dependent on what the UK Government might do, purely in terms of our ability to fund it.”3

The Chancellor announced in the UK Spending Review that he is considering business rates relief but will do so in light of the evolving situation, so reliefs for 2021-22 will be decided and set out in the New Year. This raises the significant risk for the Cabinet Secretary that this information may not be available to inform the Scottish Budget. Therefore, she explained that, “rather than assessing the Scottish economy, understanding businesses and then coming to a conclusion on that policy, as any normal Government would do when setting its budget, we are looking to the UK Government and trying to guess what it might do and what consequentials might flow.”

Loss of Income

A key issue raised by local government in written and oral evidence to the Committee is loss of income due to the pandemic. This includes income from car parking charges, leisure services and council tax. CIPFA told us that Local Authorities “have been hit dramatically by a loss of income and we know that we will not recover next year; it might take a couple of years for us to get back to where we were before.”1

The one-off income loss scheme is a UK Government measure designed to compensate Local Government in England “for irrecoverable and unavoidable losses from sales, fees and charges income generated in the delivery of services” in 2020/21 as a consequence of COVID-19.2

The Scottish Government has worked closely with COSLA in designing a Scottish local authorities lost income scheme and principles for the scheme have been agreed. In a letter to COSLA the Cabinet Secretary suggested that Barnett consequentials for the income loss scheme “estimated at £90 million will ensure that councils can manage the immediate loss of income they are facing and also includes support for ALEOs.”3 She also highlighted the “recently announced extra £49 million, which can be used to top up support for ALEOs.” However, COSLA told us that through their initial cost collection work they “foresee that the estimated £90m made available by Scottish Government will be insufficient to compensate councils fully for the impact of COVID on income sources.”

Additional Fiscal Flexibilities

The Cabinet Secretary and COSLA asked HM Treasury to consider a number of temporary fiscal flexibilities to support the response of Local Government to COVID-19 in the following areas:

to utilise £156 million of local authority capital budget directly for Covid resource costs;

Capital Receipts Received - Dispensation for both 2020-21 and 2021-22 through Statutory Guidance to allow Councils to place capital receipts in the Capital Grants and Receipts Unapplied Account and then used to finance Covid expenditure (revenue);

Credit arrangements - At present Councils are required by statutory guidance to charge the debt element of service concession arrangements to their accounts over the contract period. A change to the accounting treatment will allow the debt to be repaid over the life of the asset rather than the contract period, applying proper accounting practices:

Loans Fund Principal Repayment Holiday - The flexibility being offered is a loans fund repayment holiday which will permit a council to defer loans fund repayments due to repaid in either 2020-21 or 2021-22 (but not both).

Three of the four temporary fiscal flexibilities have been agreed with HM Treasury but the proposal to utilise £156 million of local authority capital budget directly for Covid resource costs has not been agreed. COSLA advised the Committee that HM Treasury’s view “remains that financial support for Local Authorities should come from consequentials and not to allow for “additionality” nor borrowing.”

The Cabinet Secretary told us that the three remaining measures taken together “will still confer a substantial additional package of spending power which could be worth up to £600 million” and this “will help address unmet funding pressures for Scottish councils both in the short term for the immediate mobilisation effort and as we move into the recovery phase.” Her expectation is that “local authorities will first consider the additional resources available from capital receipts and the change in accounting arrangements for service concession arrangements before taking advantage of a loans fund repayment holiday.”1

COSLA told us that the “fiscal flexibilities have been a positive piece of work with the Scottish Government, but they are by no means the solution” and that “none of the options is a replacement for cash.”2 They also explained that the £600m “was intended as an initial working assumption” and now that “that the technical work is being done, the financial benefit at an individual Council varies significantly and will almost certainly mean that the total benefit to Local Government will fall short” of this.

CIPFA pointed out that the agreed flexibilities are one-off measures which do not provide recurring funding and that a “number of directors of finance are considering how they can use those flexibilities to meet Covid pressures.”2

CIPFA also pointed out that “the flexibility that is available to councils varies” and “depends on councils’ loan structures and when they took out public-private partnership and private finance initiative contracts, for example.” In their view the “flexibilities will provide solutions, but they will not be a panacea. A great deal of funding has been provided, but we are still wrestling with a significant funding gap.” Audit Scotland told us that the fiscal flexibilities which have been provided “are not about additional spending power in aggregate; they move spending power across years and between years.”2

Local Government Reserves

The Cabinet Secretary has told Local Government that the additional fiscal flexibilities “should not be seen as an opportunity to maintain or grow reserves” and that they are “expected to take into consideration the contribution their reserves can make to meet their funding pressures.”

COSLA told us that there is an “acknowledgment from councils that reserves must be used.” CIPFA explained that Local Authorities “will be looking at their reserves as a way of dealing with the pandemic” but some “do not have the scope in their reserves to provide the cushion that reserves are intended to give.” They also pointed out that reserves “are similar to fiscal flexibilities: they are a one-off. They are there for councils to use in dealing with short-term shocks.”1

The Committee recognises that while it is challenging for the Cabinet Secretary to set her Budget it is equally challenging for local authorities and other public bodies to do likewise given the current crisis. The Committee welcomes the extent of the Barnett consequentials and fiscal flexibilities in supporting local government in managing their response to the pandemic.

But the Committee also notes that the uncertainty around Barnett consequentials especially in relation to business rates relief and the loss of income scheme makes it extremely difficult for both the Cabinet Secretary and local authorities to plan next year’s budget response to COVID-19. The Committee’s view is that this is a very good illustration of the asymmetry in the UK’s fiscal architecture as discussed above. Without its own borrowing powers the Scottish Government is essentially depending on policy decisions at a UK level to inform their own policy decisions in areas such as business rates relief. At the same time the Committee notes that local government is similarly depending both on UK and Scottish policy decisions to inform local decisions.

The Committee notes that reforming the devolved government’s fiscal framework to give them more scope to borrow would lessen this asymmetry. In the short-term, and without any presumption in relation to the outcome of the review of the Fiscal Framework, the Committee believes that HM Treasury should give further consideration to providing the devolved governments with greater access to borrowing via the National Loans Fund in emergency situations such as the current crisis. This could allow the devolved governments to tailor their own policy response to the pandemic if necessary in areas such a business rates relief. The Committee will write to the CST asking for a response before Christmas recess. Similarly, the Committee notes the delayed development of a fiscal framework between Scottish and local government must also address these issues.

A Human Rights Approach to Taxation

The Scottish Human Rights Commission highlighted the fact that the COVID-19 had not impacted everyone to the same extents and said that Scottish Government analysis anticipates that the following groups will be hardest hit financially: low earners; younger people; women; minority ethnic people; disabled people; those living in more deprived areas; and lone parents. It argued that the Scottish Government should adopt a human rights-based approach to taxation in Scotland. They suggest that the Scottish Government has taken limited steps towards a more progressive system of taxation but “Scotland can choose to approach COVID-19 economic recovery by creating a more progressive system that maximises available resources in line with its human rights obligations.”1

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary whether she intends to consider which individuals and businesses have done well during the pandemic and who has been hit hardest economically and to use tax policy to try to redistribute wealth to reduce inequalities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic? The Cabinet Secretary responded that the “short answer is yes.” However, she pointed out that she has narrow tax powers and it is hard “to see a fundamental shake-up of tax systems between now and the beginning of the next financial year at a time of great turmoil.”2

The Committee recognises that during the current crisis the focus of the Cabinet Secretary in setting Budget 2021-22 is on providing stability. However, the Committee believes that the desire for stability should not prevent the Scottish Government from attempting to address economic inequalities which have been exacerbated by the pandemic. The Committee will recommend in our legacy paper that our successor revisits our previous inquiry on a Scottish approach to taxation with a view to exploring how COVID-19 has impacted on the taxation system and considering options for a restructuring of the taxes which are devolved including a human-rights based approach.

Scottish Income Tax 2018/19 – Reconciliation Process

As the Committee has highlighted in previous budget and pre-budget reports, the Scottish budget is exposed to broadly two types of budget risk through the Fiscal Framework in relation to the devolution of income tax:

The first is the risk that the Scottish income tax base grows relatively more slowly than the equivalent income tax base in rUK. If this happens, then Scottish revenues are likely to be lower than the block grant adjustment. The implication of this is that the Scottish budget is worse off than it would have been had tax devolution not occurred;

The second is the risk of forecast error. This is the risk that a Scottish budget is based on a set of forecasts that turn out to have overestimated the level of funding available to the Scottish Government. If this happens, then a subsequent budget will need to address any shortfall.

It is important to note how these two risks interact. The first risk relates to the actual annual per capita growth in the level of Scottish income tax receipts relative to the level of per capita growth in the rest of the UK. The extent of this risk, therefore, does not become fully apparent until the outturn figures for income tax are published by HMRC.

The level of the second risk depends on the extent to which both the OBR and the SFC are able to accurately anticipate the extent of the first risk. This is explained by the SFC as follows—

“If, for structural reasons, Scottish income tax revenue is going to grow more slowly than UK income tax revenue, that is a problem for the Scottish budget. At the moment, it is showing up as reconciliations because the forecasters did not anticipate it. Once we start anticipating it, it will be built into the budget and the forecasts. That does not mean that it will go away; it will just pop up in the budget instead of in reconciliations.”

This means that, even though the forecasts may become more accurate over time and the size of the reconciliations become therefore smaller, the risk for the public finances does not necessarily reduce. Rather, any continuing risk arising from slower Scottish income tax growth relative to the rest of the UK would need to addressed by the Scottish Government when setting its budget rather than through the reconciliation process.

The size of the reconciliations is a consequence of forecast error in not foreseeing the differential performance of the growth in UK and Scottish income tax receipts. As the Committee noted in our pre-budget 2020-21 report the key point is that the actual higher per capita growth in income tax receipts in the UK compared to Scotland for 2017/18 has a negative impact on the size of the Scottish Budget. This negative impact would occur even if the forecasts were correct; if the forecasts at the time when the Scottish Budget was introduced for 2017/18 were more accurate then the Scottish Government would have had less funding to allocate.

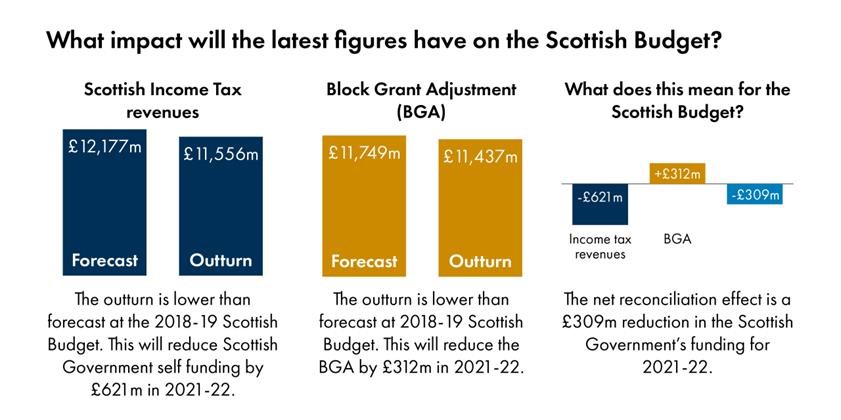

Following HMRC’s publication of the outturn figures for 2018-19 in September 2020, the reconciliation figure for Scottish income tax is -£309m as shown in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10 shows that when the 2018-19 budget was agreed by the Scottish Parliament in February 2018, the level of Scottish income tax receipts was forecast to be £428m higher than the forecast BGA. However, the outturn figures published by HMRC in September 2020 show that in fact Scottish income tax receipts were £119m higher than the BGA. This means that, based on the outturn figures, the 2018/19 budget should have been increased by £119m rather than increased by £428m. The reconciliation figure is, therefore, £309m. This will be deducted from the 2021-22 budget.

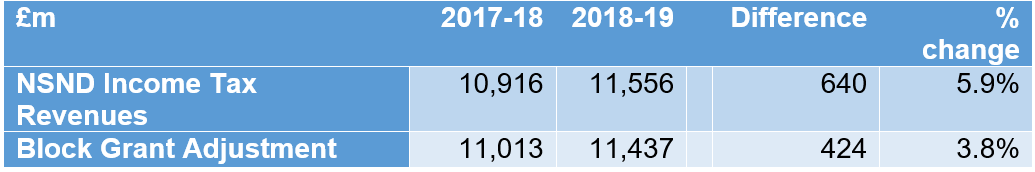

The outturn figures for 2018/19 show that the Budget would is now £119m higher than if income tax had not been partly devolved. This shown in Table 3 below where income tax revenues in 2018/19 were £11,556 million compared with the BGA of £11,437 million, a difference of £119 m.

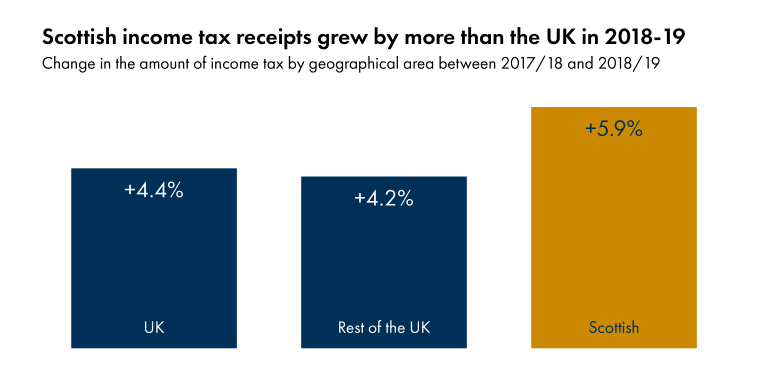

The SFC told us that the outturn for Scottish income tax in 2017-18 “was very weak” and they forecast that “that weakness would continue.” However, they explained that “in fact, the 2018-19 data show that there has been a significant bounce back in tax receipts.” 1The Cabinet Secretary explained that that between 2017-18 and 2018-19 “Scottish receipts grew more quickly than in the rest of the UK—by 5.9 per cent versus 4.2 per cent—which was driven by strong growth in receipts among high-income earners, in particular among higher-rate taxpayers.”1 This is shown in Chart 4 below.

A key question for the Committee is the extent to which the growth in income tax receipts is a consequence of changes in income tax policy and to what extent it is a consequence of relative economic growth in Scotland compared to rUK. This is discussed below.

Income Tax Policy

The Committee notes that when considering the outturn figures for income tax and the reconciliation figure it is important to be mindful of the impact of different income tax policy in the UK and in Scotland. In 2018-19 the UK Government increased the threshold for the 40p rate from £45,000 to £46,350. This would have resulted in a reduction in rUK income tax revenues and therefore a lower BGA.

2018-19 was also the first year of the Scottish Government’s new five band system for income tax and tax rates were increased for the higher and additional rates of taxation by 1p to 41% and 46% respectively. This means, as noted by the SFC, that “faster growth in Scottish income tax revenues compared to the BGA is explained in part by income tax policy changes in Scotland to raise additional revenue.”1 The 5-band system introduced in 2018-19 is now estimated by the SFC to have raised £197 million in that year, compared to the £219 million it initially estimated.

Our Adviser points out that while the outturn for Scottish income tax receipts is £119m higher than the BGA “this follows increases in taxes in 2017-18 and 2018-19 that would have been expected to raise over £250m.” This means the underlying tax base in Scotland has grown by less per person than in rUK since 2016-17 but as our Adviser notes “the difference is only modest.”2 The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) agrees that the difference is “fairly marginal” but points out that while the tax increases for 2018/19 did boost the budget by £119m “this is a disappointment given the original forecasts implied a budget boost of £428m.”3

Earnings Growth

The Committee has previously considered the extent to which differences in the relative growth in income tax revenues in Scotland compared to rUK are a consequence of differences in average earnings growth. In our pre-budget 2020-21 report the Committee noted that average Scottish earnings have “been slightly slower than average UK earnings growth for several years now and that the magnitude of this differential varies depending on the data source considered.”1

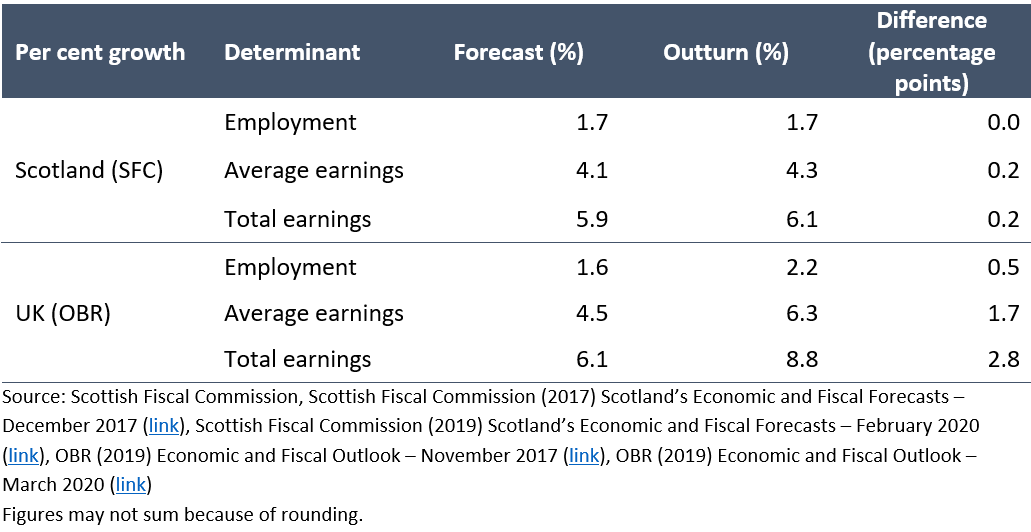

Table 4 below shows the forecast and outturn growth rates of employment and earnings growth between 2016-17 and 2018-19 in Scotland compared to the UK.

This shows that total earnings grew by 2.7% more in the UK compared to Scotland and average earnings grew by 2.0% more. It also shows that employment grew 0.5 percentage points faster in the UK compared to Scotland. Our Adviser suggests that these differences are significant in explaining the relative performance of the underlying tax base in Scotland relative to the UK.

The SFC have published additional analysis of the impact of growth in average incomes on income tax revenues in Scotland and the UK in 2017-18. They found that “all else equal, slower growth in average incomes in Scotland relative to the UK meant income tax revenues in Scotland grew by 1.8 percentage points less than in the UK, equivalent to around £156 million.”2 The SFC have committed to providing a similar analysis of the 2018-19 income tax revenue outturn figures once the relevant data is available.

The Committee notes that the outturn figures for income tax in 2018-19 provide mixed results for the Cabinet Secretary. On the one hand it is welcome that Scottish income tax receipts have bounced back from weak growth in 2017-18. However, to some extent this should have been expected given the introduction of higher income tax rates in Scotland and slightly lower rates in rUK.

More worrying is the slower earnings growth in Scotland. As noted above, total earnings grew by 2.7% more in the UK compared to Scotland and average earnings grew by 2.0% more between 2016-17 and 2018-19. In our pre-budget 2020-21 report we noted the view of our previous Adviser that “understanding the causes of the relative Scottish earnings slowdown is an ongoing priority – as is determining what the Scottish Government’s policy response should be.”1

The Committee therefore welcomes the SFC’s additional analysis of the outturn figures for income tax in 2017-18 and recommends that our successor committee examines the SFC’s future analysis of the 2018-19 figures. In the meantime the Committee invites the SFC to comment specifically on the extent of the risk of this relative Scottish earnings slowdown to the Scottish Budget in the medium-term. In particular, whether the most recent data indicates the extent to which it may be forecast to continue over the five year horizon of its next set of fiscal forecasts when these are published in January 2020-21.

The Committee also invites the Cabinet Secretary to comment on the slower earnings growth in Scotland and whether she is concerned about any medium to longer term impact on the Scottish Government’s budget and if so how this has influenced policy direction and spending allocations.

Conclusion

The Committee recognises the enormity of the economic and fiscal challenge facing the Scottish Government in preparing next year’s Budget. At the same time the Committee welcomes the extent to which the Fiscal Framework has protected the Scottish Budget, as it should, from the impact of the economic shock caused by COVID-19.

But the Committee also notes that the extent of the economic shock has highlighted an asymmetry in how the Fiscal Framework operates in an emergency situation. On the one hand, Scotland has benefitted significantly from the unprecedented peacetime levels of UK Government borrowing both in terms of UK-wide economic measures and from Barnett consequentials in devolved areas. But without its own borrowing powers to fund day to day spending, the Scottish Government is largely constrained by UK spend and policy decisions when determining its own COVID-19 related spending and policies. For example, it would be very challenging for the Cabinet Secretary to continue with policies like business rates relief, in its current form, without Barnett consequentials.

It is on this basis that the Committee recommends that in the short-term, and without any presumption in relation to the outcome of the review of the Fiscal Framework, HM Treasury should give further consideration to providing the devolved governments with greater access to borrowing via the National Loans Fund in emergency situations such as the current crisis. This could allow the devolved governments to tailor their own spend and policy response to the pandemic and economic recovery In Scotland depending on how this evolves differently from the situation in England.