Development and implementation of Regional Marine Plans in Scotland: interim report (July 2020).

Summary and next steps

In May 2019, the Committee agreed to examine the experience of developing and implementing Regional Marine Plans in Scotland, ten years on from the Marine Planning (Scotland) Act 2010 that provided the framework for Plans.

The Act envisages eleven Regional Marine Plans in total, formulated by Marine Planning Partnerships (MPPs). Currently two MPPs have been established (Shetland and the Clyde), with a third one in development (Orkney). The draft Regional Marine Plans formulated by the two MPPs have not yet been given Ministerial approval.

This report summarises information gathered by the Committee to date. In the next phase of the Committee's inquiry, the Committee intends to commission academic research exploring international comparisons of the implementation and governance of marine planning to-

better understand how the implementation of marine spatial planning can balance competing demands on the marine environment; and

deliver protection and enhancement of the marine environment

using examples from other countries and the rest of the UK.

Key issues and outstanding questions

This section provides a summary of views gathered and sets out some questions and knowledge gaps identified from the evidence the Committee has gathered in its inquiry so far. More detail is provided in the following sections.

The Committee will seek views on these outstanding questions before producing a final report and recommendations.

Theme 1: Membership and governance of Marine Planning Partnerships

Confusion over the specific role and powers of Marine Planning Partnerships and advisory groups.

A lack of flexibility in the legislation to allow for community representation and membership of Marine Planning Partnerships.

Perception of bias and vested interests in the membership of Marine Planning Partnerships.

A lack of transparency in the decision-making processes and selection of members Marine Planning Partnerships.

Overly complex governance structures and ineffective leadership.

A lack of clear guidance and input from central government.

Tensions between stakeholders leading to a lack of trust and collaboration in developing regional marine plans.

Questions

What can be considered best practice for the governance structure and decision-making processes of Marine Planning Partnerships?

How can Marine Planning Partnerships build trust between stakeholders and encourage collaboration on the development of Regional Marine Plans?

What barriers exist to stakeholders taking on a role as a delegate and how can they be resolved?

What lessons have been learned from existing Marine Planning Partnerships and how will this be communicated to other marine regions seeking to progress regional marine planning?

How should conflicts of interest and disagreements in the decision-making process of Marine Planning Partnerships be resolved?

What role should central government play in delivering regional marine planning?

Theme 2: Scope and expectations of Marine Planning Partnerships and Regional Marine Plans

Confusion over the scope and expectations of regional marine planning. For example:

The legal scope of Regional Marine Planning.

The ability of Regional Marine Planning to deviate from, or go above and beyond policies in the National Marine Plan.

Confusion over the role and powers of Marine Planning Partnerships.

The ability to include management policies to deliver protection and enhancement of the marine environment.

The relationship between Marine Planning Partnerships and Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups.

Questions

Are the powers of Marine Planning Partnerships and the legal scope of Regional Marine Plans sufficient to balance policies for sustainable economic development with the mitigation of climate change and protection and enhancement of the marine environment?

How should Marine Planning Partnerships interact with Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups?

Do the policies and objectives of the National Marine Plan provide sufficient scope to respond to the external crises such as climate change, biodiversity loss and a health pandemic (such as COVID-19) at a regional level?

Theme 3: Finance, resources and expertise

The following key issues were identified in written evidence and visits

A lack of human, financial and political support to deliver regional marine planning, particularly in the following areas:

Staff, marine planning expertise and resources for Marine Planning Partnerships.

Funding and expertise for research, data collection and monitoring.

Insufficient funding for the wider roll out of Regional Marine Planning

A lack of resource within Marine Scotland to support Regional Marine Planning.

Questions

How should regional marine planning be financed in the emerging economic context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

How can links between Marine Planning Partnerships and academic expertise in marine science be strengthened to enable targeted research, data collection and monitoring work to support regional marine planning?

What is required to raise the professional status of marine planning to meet the demands of effective marine planning in Scotland?

Theme 4: Community and stakeholder engagement

Mixed perceptions on the quality and effectiveness of community and stakeholder engagement influenced by regional differences in geography and social cohesion.

Legislation too restrictive in providing formal community representation in regional marine planning.

Local knowledge is not being used effectively.

Questions

What can be considered best practice for community engagement in regional marine planning?

What changes in legislation are needed to increase opportunities for community representatives in regional marine planning?

How should wider Scottish Government policy on community empowerment be integrated into regional marine planning (e.g. Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 and the National Islands Plan)?

Introduction

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is defined by UNESCO as:

"a public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that usually have been specified through a political process”.

MSP is driven by international commitments and obligations and EU policy drivers such as the EU Integrated Maritime Policy, Blue Growth, Water Framework Directive, Marine Strategy Framework Directive, Habitats Directive, Common Fisheries Policy, Renewable Energy Directive and Marine Spatial Planning Directive.

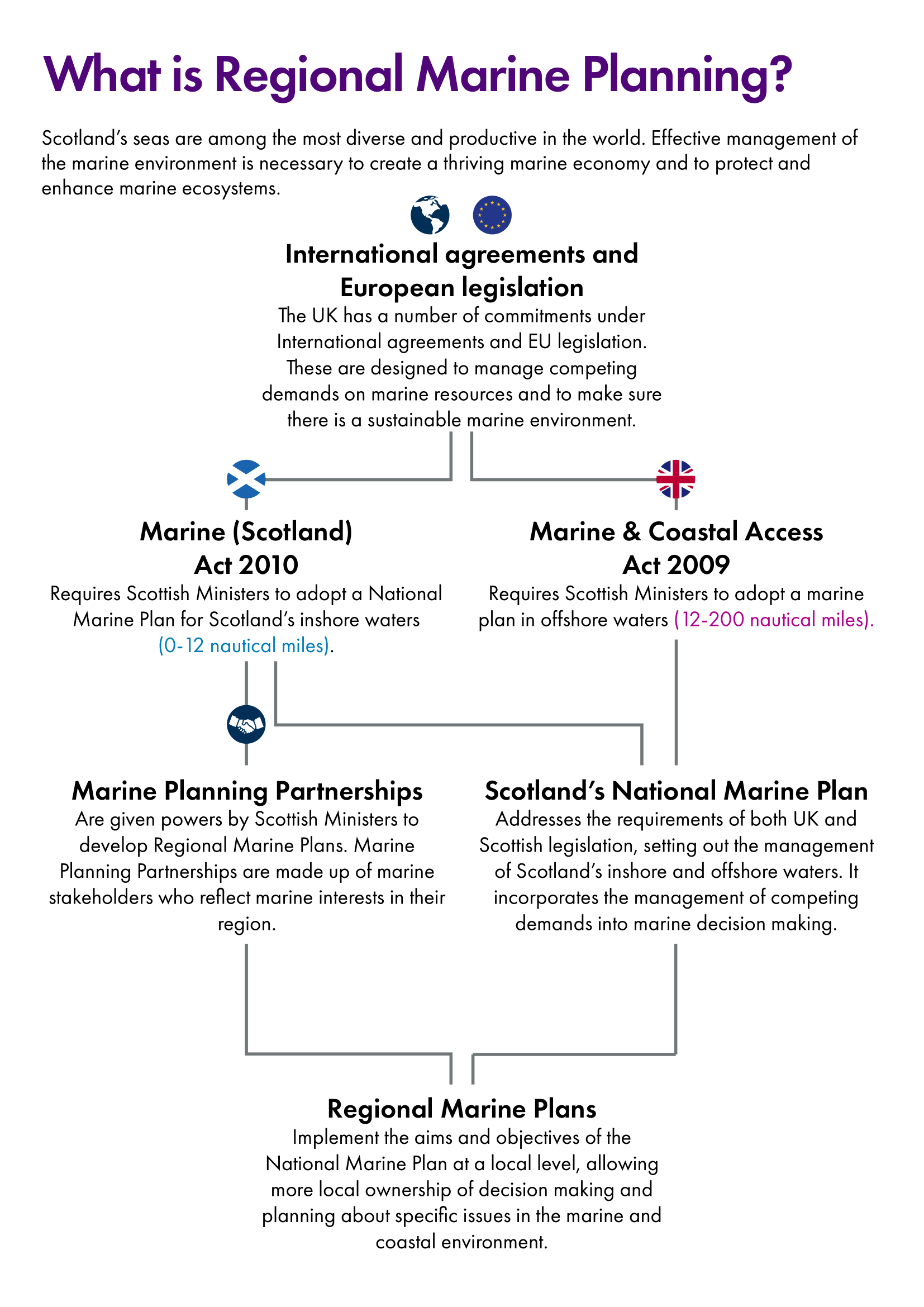

The legal framework for MSP in the UK was initiated by the Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009) and in Scotland by the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. The Marine (Scotland) Act contains provisions for both a national marine plan and regional marine plans (Part 3).

What is regional marine planning?

The Scottish Government, via Marine Scotland, first piloted regional marine planning in 2006 through the Scottish Sustainable Marine Environment Initiative (SSMEI). Four pilot areas were selected:

The Firth of Clyde

Shetland Isles

The Sound of Mull

Berwickshire coast

The overarching aim of the SSMEI was to develop and test the effectiveness of differing management approaches to deliver sustainable development in Scotland’s coastal and marine environment.i

An evaluation of SSMEI was undertaken by Marine Scotland and published in March 2010. The evaluation noted that it can take a long time to establish partnerships and highlighted some key concerns around funding and expertise.

Amongst its conclusions, the evaluation noted:

• many of the pilots had difficulty in translating the high level principles into operation and it would be helpful to develop some practical guidance to assist future marine planners with this.

• a need for appropriate training to create marine planners in the future.

• having different options for the remit, responsibilities and structure of future Scottish Marine Region Marine Planning Partnerships based on the experience of the SSMEI local steering groups.

Provision for the creation of Marine Planning Partnerships (MPPs) and Regional Marine Plans (RMPs) is set out in Part 3 of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 (enacted in February 2010) through Ministerial Direction. Delegates are known as ‘Marine Planning Partnerships.’

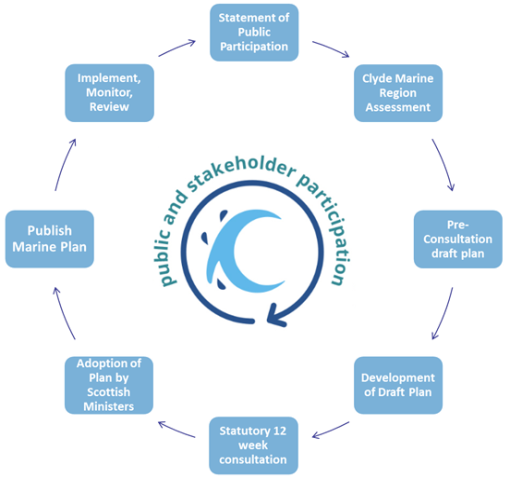

Marine Planning Partnerships are made up of marine stakeholders who reflect marine interests in their region. The partnerships can vary in size and composition depending on the area, issues to be dealt with and the existing groups. Local Authorities, Inshore Fisheries Groups, Local Coastal Partnerships and their umbrella body, the Scottish Coastal Forum, play a role in the development of RMPs. The diagram below provides an example of the process of developing and implementing a regional marine plan.

Figure 2: Clyde Marine Planning Partnership  Source: Clyde Marine Planning Partnership

Source: Clyde Marine Planning Partnership

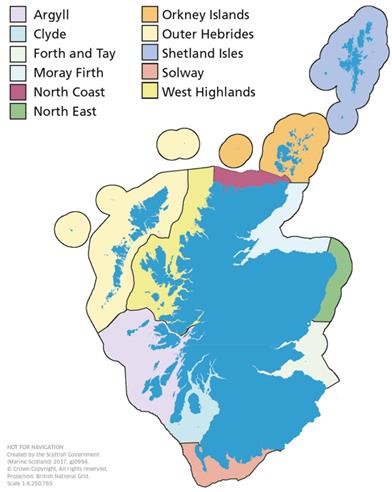

Eleven Scottish Marine Regions have been created which cover sea areas extending out to 12 nautical miles (see map below). RMPs will be developed in turn by MPPs; the intention of the policy is to enable local 'ownership' and decision making about specific issues within an area.

So far, regional marine planning is being progressed in three marine regions-

Shetland: The Shetland Isles Marine Planning Partnership received ministerial direction on 22 March 2016. It comprises the Shetland Islands Council and the NAFC Marine Centre. A draft regional marine plan was published in 2019. A public consultation on the draft plan ran from 9 September 2019 to 30 December 2019.

Clyde: The Clyde Marine Planning Partnership received ministerial direction on 14 March 2017 and comprises 24 members. The Clyde MPP opted for an additional pre-consultation phase and published a pre-consultation draft plan on 18 March 2019. A consultation ran from 18 March to 27 May 2019. The Clyde MPP is now working on a draft regional marine plan which will go out for further consultation before being submitted to Minsters for approval.

Orkney: The Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership is currently awaiting Ministerial Direction. It is expected that the Orkney Islands Council will be the sole delegate of the Marine Planning Partnership.

Background to the Committee's inquiry

In May 2019, the Committee issued a call for evidence on the development and implementation of RMPs.

The Committee received 33 evidence submissions. This report includes a summary of key themes from the evidence which can be found from page xxxx (the submission from the Clyde Marine Planning Partnership includes a ‘lessons learned’ report and can be found here).

Following this, the Committee agreed to investigate the issues raised in more detail with the Marine Planning Partnerships, and undertook visits to Shetland, Clyde and Orkney in November 2019 (the key themes identified from these visits can be found from page xxxx). The Committee also launched an online engagement platform to coincide with the visits.

Key themes emerging from written submissions

A number of themes emerged from the written evidence. These are summarised below:

The objectives of establishing Scottish Marine Regions are still appropriate to deliver the National Marine Plan.

The process for developing MPPs and RMPs is overly complex leading to slow progress.

Increased human, financial and political resources are required to deliver RMPs for remaining Scottish Marine Regions.

Greater transparency and community representation in the formation and activity of MPPs is needed.

There should be a greater emphasis on protection and enhancement of the marine environment and climate change mitigation and adaptation in marine planning.

There is a greater need for integration between Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups and MPPs.

There is a need for improved co-ordination between adjacent marine regions.

These themes are expanded on in the following pages.

Are the objectives for the establishment of the Scottish Marine Regions still appropriate?

There was broad agreement from the evidence that the aims and objectives of establishing Scottish Marine Regions are still appropriate. Most submissions referred to a regional approach as being necessary to provide the regionally specific detail to deliver the aims and objectives of the National Marine Plan.

However, there was also acknowledgement that a lack of progress in establishing RMPs makes it difficult to assess whether specific objectives are still appropriate.

Evidence also called for greater clarity and publicity of objectives as well as clear guidance for stakeholders, Local Authorities and communities on how the delivery of objectives can be measured.

Submissions from environmental NGOs stated that a decentralised approach to marine management was essential to deliver an ecosystem-based approach to Regional Marine Planning.

For example, Scottish Wildlife Trust stated that RMPs provide the required mechanism to deliver an ecosystem-based approach and should consider a natural capital approach to marine planning, considering the state of marine natural capital assets (e.g. fish stocks and habitats).

Progress with developing and implementing Marine Planning Partnerships and Regional Marine Plans

A common theme in the evidence is dissatisfaction over slow progress in establishing MPPs and the development of RMPs. Many submissions cited a lack of human, financial and political support.

The Financial Memorandum to the Marine (Scotland) Bill 2009 based estimates on assumption there would be ten RMPs in total with two plans starting each year between 2012-13 & 2016-17.

Fig. 3: Scottish Marine Regions

Only two MPPs have been established (Clyde and Shetland) and Orkney is currently leading the development of the Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership with the aim of establishing the partnership in 2020.

Evidence indicated a need for clarity from the Scottish Government over the future timetable for roll-out of remaining RMPs and if it is still committed to the policy aims of regional marine planning.

Submission from the Orkney Islands Council (OIC) stated:

“…regional marine planning is losing momentum and lacks leadership and resources from the Scottish Government.”

The submission from Dr Tim Stojanovic (University of St Andrews) identified that national leadership and long-term political commitment were key to successful marine planning in international examples.

OIC stated the following reasons for a lack of progress:

A significant lack of funding and resources from the Scottish Government to enable local stakeholders to set up MPPs and deliver regional marine plans.

The provisions of Marine (Scotland) Act, s12, are too prescriptive and are not adequately flexible to allow locally appropriate governance arrangements to be established to delegate regional marine planning functions to the local level.

Limited staff resource and expertise within local stakeholder organisations is a major barrier to these organisations undertaking a delegate role with responsibility for delivering regional marine planning functions on behalf of Scottish Ministers.

There is no acknowledgement within the Marine (Scotland) Act of the potential advisory role for local stakeholder organisations as a mechanism to provide economic, environmental, community and recreational representation within MPPs. An advisory role is often a more practical and proportionate way for local stakeholders to participate in regional marine planning as opposed to taking a delegate role.

Local stakeholders in Orkney have expressed the view that the marine planning policy is particularly top down, and there is a relatively narrow set of issues that local people can influence through regional marine planning. Many policies and constraints have been defined at the international or national level, particularly for nature conservation, fisheries, shipping and renewable energy development, for example. There needs to be greater scope for local solutions to be found to marine issues to realise the potential of MPPs and regional marine planning. In this regard, OIC welcomes the Islands (Scotland) Act provisions to undertake Islands Community Impact Assessments and the resulting identification of islands appropriate policies and decisions.

Submissions also highlight that slow progress has implications for how RMPs will interact in adjacent marine regions if they are developed on different timescales. This may affect the 5-year statutory review cycle. It may also lead to a patchwork of RMPs with some regions receiving more support than others.

The following key themes were also identified in establishing MPPs and the implementation of RMPs:

Process for establishing MPPs:

The process of Regional Marine Planning is more complex and protracted than originally anticipated and does not provide flexibility for appropriate governance.

The process under s12 of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 should be simplified and the process of forming MPPs clarified.

Reluctance of user groups and interests to adopt a role as a statutory delegate in MPPs.

Lack of community representation in MPPs.

Transparency:

Lack of transparency in the process and selection of MPP member organisations.

Membership of MPPs should be drawn from public consultation.

Meetings of MPPs are not transparent and information on meetings is not available to the public.

Interaction with Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups (RIFGs):

Lack of clear guidance on how RIFGs and MPPs should interact.

RIFGs Management Plans should be developed in tandem with RMPs.

RIFGs should be embedded within the broader framework of the RMP system. However, MPPs should also take into account other stakeholder views on fisheries.

Effective use of existing Local Coastal Partnerships (LCPs):

Better utilisation of existing LCPs can provide a cost-effective way of delivering RMPs.

LCPs can perform the function of MPPs if Local Authorities, SEPA and others engage with them.

‘Sectoral Interaction Matrices’ developed by Local Coastal Partnerships currently able to resolve conflicts. RMPs may not be necessary.

Enhancement of the marine environment and climate change:

RMPs should place more emphasis on enhancement of the marine environment.

RMPs should manage conflicts between the fishing sector and other users of the marine environment to ensure sustainable fisheries and marine conservation.

Lack of clarity around how and by whom work is to be delivered. Clearer guidance required on roles and responsibilities in MPPs.

Funding and resources

Evidence indicated that there is currently limited-to-no funding available for developing RMPs. It also highlighted that any funding available is significantly lower than was set out in the Financial Memorandum to the Marine (Scotland) Bill 2009.

Submissions indicated that adequate funding is needed to deliver the required level of:

Marine planning expertise.

Scientific evidence base and monitoring.

Stakeholder and community engagement.

Evidence suggested that some Local Coastal Partnerships have undertaken preparatory work but with “shoestring resources” in comparison to established MPPs.

Orkney Islands Council identified a lack of certainty in funding available for long-term planning. Regional Marine Planning is a statutory function to be delivered over a long-term planning cycle, but currently no long-term finance is available.

Evidence revealed that some Local Authorities have explored external funding streams to carry out statutory work but that options are limited, and statutory work is normally excluded.

For example, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar submitted a bid for EU INTERREG programme funding of £40K per annum over three years to fund a Marine Region State of Environment Report but was unsuccessful. The Council is seeking powers to develop an RMP but currently has no resource to do so.

North Ayrshire Council, a member of the Clyde Marine Planning Partnership, explained that it has no financial resource for monitoring of the existing Clyde Marine Plan.

Aberdeenshire Council stated that it is not aware of any funding to support Regional Marine Planning.

Marine Planning expertise in Local Authorities

Evidence provided a mixed picture of available expertise in marine planning. Some terrestrial planners have limited experience related to aquaculture. Others, such as Shetland, have access to planning and scientific expertise. However, some local authorities highlighted that they currently have no requirement for marine planning expertise.

Evidence from the Royal Town Planning Institute Scotland (RTPI) explained that local authority planning departments have seen disproportionally large cuts to budgets in last ten years compared to other departments. It stated that there has been a 25% decrease in planning staff and 40% real term cut in budgets since 2009.

Aberdeenshire Council stated that “marine environmental knowledge and experience is largely outside of the skills and training of existing staff”.

Evidence suggested that increased funding was necessary to provide opportunities for existing terrestrial planners to diversify and specialise. Furthermore, long-term funding is needed to enable recruitment of staff on longer-term contracts with competitive salaries to attract required personnel.

Integration of marine and terrestrial planning

A number of submissions referred to Scottish Government Planning Circular 1/2015 which describes how integration of marine and terrestrial planning should happen. However, evidence suggested that there is little experience of this working in practice.

Evidence also suggested that it is not possible to determine how integrated these planning systems are until more RMPs have been developed.

The Orkney Islands Council submission explained that:

“marine planning and licensing covers marine areas up to mean high water springs and terrestrial planning extends to mean low water springs. There is a resulting jurisdictional overlap of these regimes in the intertidal zone and an essential requirement for joined up working between planning agencies.”

As such, evidence noted that integration was particularly important for regions with a large intertidal range.

Evidence submitted was in broad agreement that terrestrial planning applications need to have regard to marine policy and vice versa. Scottish Environment Link noted how activities on land can impact marine via land surface run-off and rivers, resulting in pollution and eutrophication.

Aberdeen Council stated that a lack of integration results in inconsistent approaches at the coast and are not well catered for Environmental Impact Assessments. For example, the placement of offshore windfarms and associated landfall and substations.

What is required for an effective marine planning system?

Evidence broadly support the aims of the National Marine Plan but that RMPs are required to implement high-level policy aspirations of NMP at regional level. It also suggests that RMPs should reflect NMP policy direction but have flexibility to deviate based on local needs/engagement.

Broadly speaking, evidence prioritises:

increased funding and resources.

improved clarity and guidance on the development of RMPs.

improved co-ordination with adjacent marine regions.

The Law Society of Scotland listed the following requirements for an effective marine planning system:

Clarity as to the role of regional marine planning, what is to be achieved by the plans and how these outcomes are to be achieved;

Clarity as to the roles and responsibilities of all those involved in development and delivery of the Plans;

Assessment of the impact of the plan on businesses and organisations;

Clarity as to how the plan fits with the terrestrial planning system and other legislation, including marine licensing and harbour matters;

Clarity around compensation to businesses and organisations affected by the plan;

Appropriate and suitably qualified resources in place by the Marine Planning Partnerships;

Mechanisms for measuring success and evaluating the plan.

The Orkney Islands Council list the following priorities

Support established and emerging MPPs;

Support wider roll-out of RMPs;

Increase funding and resources;

Clearer policy guidelines for MPPs and RMPs and disseminate best practice;

Review Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 provisions governing the structure of MPPs to enable greater flexibility when establishing locally appropriate governance arrangements;

The Scottish Government and partners should disseminate benefits of RMP to key stakeholders;

Support and fund MPPs to identify and address social, economic and environmental data gaps to underpin future policy and spatial planning for development/activities.

There was acknowledgement that the current model for financing RMPs is not working and that alternatives need to be explored. Scottish Environment Link suggest that discussions are needed on whether marine industries that profit from the marine environment should contribute towards conservation, enhancement and management. This could be explored through a Crown Estate or industry levy.

Some evidence suggested that enhancement of the marine environment and Climate Change adaptation and mitigation should play a more central role in marine planning to tackle challenges such as:

Transition to a low carbon economy.

Deployment of Carbon Capture and Storage technology.

Protection of blue carbon.

Allowing recovery and enhancement.

Some evidence also suggested that there should be stricter duties on Local Authorities to establish RMPs but that this should come with the necessary funding from the Scottish Government.

Royal Town Planning Institute Scotland suggested that new Regional Spatial Strategies (RSSs) in the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019 could be explored as a model to change RMPs to allow a more flexible approach of working. It also stated that objectives over the next 5-10 years should be integration of regional marine planning with:

National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4).

Regional Spatial Strategies.

Local Development Plans.

The Infrastructure Investment Plan.

Fact-finding visits by the Committee: summary of meetings and key themes

Introduction

In November 2019, the Committee conducted visits to Shetland, the Clyde and to Orkney to speak to MPPs, members of the community and other stakeholders to gather views on regional marine planning.

A list of organisations the Committee met for each visit is provided in Annex 1.

Regional Marine Planning visits - key themes

Five key themes emerged from discussions during the visits:

Membership and governance of Marine Planning Partnerships

Scope and expectations of Marine Planning Partnerships and Regional Marine Plans

Relationships and collaboration between stakeholders

Finance, resources and expertise

Community and stakeholder engagement

These themes form the basis for the summary of discussions held during each visit (below).

THEME 1: Membership and governance of Marine Planning Partnerships

The Orkney Islands Council (OIC) is currently leading the development of the Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership with the aim of establishing the partnership early in 2020 as the sole delegate.

Shetland

The delegated Shetland Isles Marine Planning Partnership (SIMPP) is comprised of two members, the NAFC Marine Centre, University of the Highlands and Islands (NAFC UHI) and the Shetland Islands Council (SIC). It is also supported by a stakeholder advisory group.

The Shetland Islands Draft Regional Marine plan is the 5th iteration of a marine spatial plan in the Shetland Islands since the SSMEI pilot marine spatial plan in 2006. The first three editions were voluntary. The fourth edition was incorporated as supplementary guidance in the SIC’s statutory Local Development Plan. The current draft SIRMP will be the first RMP under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010.

The Committee heard from stakeholders that overall there was strong leadership from the SIMPP and trust in its leadership had been built among industry and environmental stakeholders. The importance of the marine economy also meant that the SIMPP had good skills and expertise in marine planning and science.

It was recognised that a history of marine spatial planning in Shetland meant that early problems had been resolved. For example, fisheries stakeholders stated at the outset that there was confusion about what the MPP might do and what role the advisory group would play. Environmental stakeholders stated that it was “woolly” at the outset. Without a long history of marine planning, stakeholders said it would have needed more guidance from central government.

Representatives of the SIC stated that provisions for the membership of MPPs under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 (Section 12) were too restrictive and did not allow for community representation in the SIMPP.

Clyde

The Clyde Marine Planning Partnership (CMPP) is comprised of 24 members with representation from local authorities, industry and environmental stakeholders, public bodies and the Crown Estate. The CMPP also has a board responsible for decision-making when three or more MPP members object to a proposal.

A voluntary Firth of Clyde Marine Spatial Plan (2010) was developed as part of the SSMEI programme between 2006 and 2010. This plan was led by the Firth of Clyde Forum which later formed the basis for core membership of the CMPP.

Compared to Shetland, the Clyde marine region is more complex with a greater number of stakeholders, local authorities and competing demands on the marine environment leading to greater tensions between stakeholders. This was evident in discussions with stakeholders throughout the visit to the Clyde. Key themes regarding the membership and governance included:

Perceived bias in CMPP membership

Transparency in the structure and governance of the CMPP

The role of the Clyde 2020 Research Advisory Group

Perceived bias in CMPP membership

There were conflicting views from different stakeholders on the perceived bias of the CMPP towards either industry or environmental interests. Environmental stakeholders said that representation had improved on previous voluntary partnerships but stated the CMPP was “not fit for purpose”. Some environmental stakeholders also felt that mobile fisheries representatives held the power in the CMPP and pointed to a lack of spatial management measures in the draft Clyde Regional Marine Plan (CRMP) as indicative of this

Contrary to these views, fisheries stakeholders thought that the composition of the CMPP, with only 3-4 representing industry interests demonstrated there was more of a bias towards environmental interests. They were concerned that many are anti-mobile fishing and that the balance of stakeholders would affect CMPP votes on decisions.

Members of the public and representatives of Community Councils at the Committee’s evening stakeholder event held in Troon thought that the CMPP was mainly represented by industry and business interests. There was also a misunderstanding of the role of the CMPP and its powers to enforce or regulate marine activities in the Clyde.

A marine recreation stakeholder said that meetings of the CMPP were attended by around 20-25 people but that only around 7-8 voices were making themselves heard. Its described one environmental stakeholder as being particularly vocal in pushing back against development.

Transparency in the structure and governance of the CMPP

One environmental stakeholder felt that the CMPP had suffered from the complexity of the region and inherited structures from the previous voluntary partnership under the Clyde Forum. Its view was that the size of the CMPP membership and its relationship with the CMPP Board was not effective.

Fisheries stakeholders also said that the CMPP suffered from “baggage” and that if it was starting from scratch it would be designed differently. They also said there is a lack of transparency over the work of the CMPP and over how members are selected. In particular, they raised concerns over one environmental stakeholder's membership as a recreational angling group.

One marine stakeholder explained that it was given a place on the CMPP because of previous membership of the Clyde Forum. It's view was that it wasn’t clear from the start what the CMPP was meant to do.

Stakeholders identified a lack of leadership in decision-making and clarity over roles as being a problem in the CMPP. A lack of trust was also identified which prevented good collaboration between stakeholders

The role of the Clyde 2020 Research Advisory Group.

Fisheries stakeholders and environmental stakeholders sought clarity over the role of the Clyde 2020 Research Advisory Group (RAG). One environmental stakeholder’s view was that the Clyde RAG had been under-utilised and wanted to ensure the CMPP is science-based.

Fisheries stakeholders explained that the Clyde 2020 group was now a subcommittee of the CMPP but that its relationship with the CMPP is unclear.

Orkney

There was no feedback on the Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership (OIMPP) because it is not yet operational. However, concerns were raised over the OIC becoming the sole delegate.

The fisheries and environmental stakeholders and members of the public who attended the evening stakeholder event in Kirkwall all raised concerns over potential conflict of interest with the OIC as the delegate and a corporate body (as the statutory harbour authority). A fisheries stakeholder suggested that Marine Scotland should have some oversight to deal with potential conflict of interest. It also suggested having the power of veto or a ranking system for members of the advisory group to ensure decisions are not made to the detriment of individual stakeholders.

Elected members of the OIC also suggested the need for Marine Scotland to play a role in providing expertise and by having more of a role in the region as opposed to having it's homework marked”. In discussion in the the Committee’s online engagement platform, OIC also stated:

“The ‘Lessons Learned’ report from the pilot Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters Marine Spatial Plan (PFOW MSP) provides a useful starting point for the subsequent statutory RMPs. The work published to date from the PFOW MSP, Shetland and Clyde also provide guidance on the topics to cover and issues to address. There appears however to be very limited national guidance or input available to support the marine regions.” (emphasis added).

The OIC said that it was difficult to bring forward a governance structure under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 because of a lack of flexibility under section 12 (Delegation of functions relating to regional marine plans). The OIC recommended that the role of the advisory group should be formalised in the Act. The International Centre for Island Technology (ICIT), Heriot-Watt was approached to be a delegate in the OIMPP. However, the university had concerns about being a statutory delegate and over what funding it would receive for the role. These negotiations ended when the OIC applied as the sole delegate after the amendment of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 under the Islands (Scotland) Act 2018.

THEME 2: Scope and expectations of Marine Planning Partnerships and Regional Marine Plans

Understanding of the scope of Regional Marine Plans and expectations of what they could deliver was a recurring theme during the visits. Key issues included:

The legal boundaries of Regional Marine Planning

The ability of Regional Marine Planning to deviate from the National Marine Plan

Confusion over the role and powers of Marine Planning Partnerships

Ambition to deliver protection and enhancement of the marine environment

Shetland

Stakeholders were supportive of the current draft SIRMP. The Committee heard that the importance of the marine economy to Shetland meant that industries were aware that they cannot exist unless the marine environment is protected. Stakeholders also acknowledged that the current version was mainly “tweaking” previous iterations of non-statutory Shetland Islands Marine Spatial Plans.

Marine planning has been implemented in Shetland since the devolution of marine licensing powers to Shetland local authorities through the Zetland County Council Act 1974. This is likely to contribute to a greater understanding of the scope and limitations of marine planning among stakeholders

Stakeholders spoke to the Committee about what its priorities for future plans are. These included:

Improving fish farm placement to achieve maximum capacity with minimum environmental impact

Developing marine tourism

Balancing the needs of oil & gas and renewables

Greater emphasis on climate change and blue carbon storage

Clyde

In the Clyde, the Committee heard conflicting views from stakeholders on their expectations of the content of CRMP and what it should deliver. Some stakeholders wanted the plan to be ambitious in protecting and enhancing the marine environment. This included the expectation from some environmental stakeholders that the CRMP would include zoning of marine activities and spatial management of fishing activities.

Other stakeholders saw the CRMP as being limited to a regional version of the National Marine Plan. Fisheries stakeholders were concerned that the plan would take on fisheries management measures which were outside the legal scope of the CMPP. Their view was that the plan should be limited to providing statutory guidance for marine development.

Environmental stakeholders

Environmental stakeholders were frustrated over a lack of ambition in the CRMP for providing enhancement and protection of the marine environment and tackling climate change. These concerns were also raised by community council representatives and members of the community at the Committee’s evening stakeholder event in Troon.

Environmental concerns raised by stakeholders included the following:

Bycatch, discards and seabed damage by mobile fisheries (prawn trawling)

Dumping of hot waste from distilleries into sea lochs

Expansion of finfish aquaculture

Wrasse fisheries

Electrofishing trials for razor clams

Failed biodiversity targets and climate change

Illegal fishing in Marine Protected Areas

Unregulated creel fishing

Environmental stakeholders were critical of what they perceived as a lack of ambition in the draft CRMP. For example, one stakeholder referred to the draft CRMP as “mediocre and diluted” and that it was a “rigged plan”. Another said the plan was the “status quo”. One stakeholder also questioned the purpose of the CMPP, asking if it was “just a talking shop”. There was also criticism of a lack of measurable objectives for future monitoring of the plan.

A community council representative said the draft CRMP was the National Marine Plan “rewritten”. Another environmental stakeholder said that if the plan was just reiterating the National Marine Plan then it was a “waste of time”. Stakeholders highlighted the amount of voluntary work that had gone into plan and concern that this effort would be wasted if the plan was diluted.

Environmental stakeholders attributed the perceived lack of ambition to mobile fisheries wanting to maintain the status quo and the reluctance of Marine Scotland to include any policies on natural heritage and fisheries that could be open to legal challenge. Marine Scotland was also criticised for taking a “hands-off” approach with the CMPP.

Industry stakeholders

The Committee heard concern from industry stakeholders that the draft CRMP was going beyond its statutory scope. Fisheries representatives said that management measures had been introduced into the plan that were the responsibility of Marine Scotland and not the CMPP.

One stakeholder said that it hoped that the CMPP would be able to act as the “referee in the room” to balance the need of different stakeholders. It was concerned that some environmental organisations wanted to use the CMPP as a tool to reduce mobile fishing activity in the Clyde which is important for employment in the Clyde region.

A marine recreation stakeholder said that sustainability was often discussed in the draft CRMP in an environmental context but not in a business/economy context. It criticised the draft CMPP for having only three pages dedicated to industry and commerce.

With regards to legal scope, its view was that Marine Scotland was setting the legal boundaries of the CRMP rather than diluting it and that didn’t want to go to Ministers to seek an extension of powers for the CMPP. This stakeholder also said that there should have been clear guidance from the start of the process from Marine Scotland. Uncertainties also remain over the ability of the plan to include zoning of activities and legal liability for licensing certain activities.

Marine Planning Partnership staff

The MPP Staff explained that it was a challenge for the MPP in understanding the scope for the partnership and expectations that might be raised. During public consultations the MPP heard key issues from the public such as:

Climate Change

Aquaculture and fisheries

Natural heritage

MPAs

The MPP said that Marine Scotland and the Scottish Government wanted the MPP to be at “arms-length” and couldn’t provide legal advice. There was some confusion over why this was the case but it was suggested that it may be because Ministers are responsible for approving RMPs and wanted to avoid a conflict of interest. The MPP was due to discuss these issues with Marine Scotland during a meeting of the CMPP on 3 December 2019.

Community stakeholders

Concerns raised at the Committee’s stakeholder event included:

A lack of coordination between local authorities on siting of new fish farms

Illegal fishing in Marine Protected Areas

Confusion over who is responsible for marine activities (CMPP, Marine Scotland, Local Authority, Port Authority etc).

The impact of jet skis on cetaceans

Some attendees were under the impression that the CMPP had enforcement and compliance powers to deal with these issues.

Orkney

Conversations in Orkney were more focussed around aspirations rather than issues because the MPP is not operational yet. As is the case in Shetland, the Orkney Islands Council (OIC) also has statutory licensing powers of its harbour areas under the Orkney County Council Act 1974.

Marine Planners in the Orkney Islands Council (OIC) said that they wanted to deviate from the National Marine Plan for a more localised approach, otherwise there was no point in developing an RMP. This included the tackling wider issues such as marine plastic pollution.

The OIC also said it was looking towards its climate change responsibilities, particularly with regards to developing renewable energy technologies. The OIC recognised that the non-statutory pilot Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters Marine Spatial Plan had been important for managing expectations.

A fisheries stakeholder raised some concern over what it referred to as a “land mindset” and that a one-dimensional approach might be taken that is unsuitable for a dynamic marine environment. They said that marine planning needed to take into account the “hunter gatherer” method of fishing that varied depending on changing conditions at sea.

Heriot-Watt University and renewable energy stakeholders saw the MPP as an opportunity for collaboration with other stakeholders and for innovation in planning required for renewable energy.

Evening stakeholder event

Members of the community attending the Committee’s stakeholder event spoke of concerns about the pressure of cruise ship tourism on the island’s public services. They were also concerned about the changing demographic of the islands and the sustainability of its population.

Some wanted marine planning to enable better development of port infrastructure in the smaller islands to promote long-stay tourism. Others questioned how Crown Estate revenues were being spent and whether that money could be used for marine planning and development.

There was also concern over action and resources available to tackle environmental issues such as climate change, seabird decline and invasive species.

THEME 3: Relationships between stakeholders

Relationships between stakeholders varied between each location visited. Tensions and distrust between stakeholders were more evident in the Clyde compared to Shetland and Orkney. Stakeholders spoke of a lack of collaboration in the Clyde, with stakeholders more focussed on representing their respective interests.

Shetland

The Committee heard that in Shetland there was a good spirit of collaboration and understanding between stakeholders. Central to this was the cohesive nature of Shetland’s community and the importance of the marine economy. Relationships between stakeholders went beyond vested interests because they knew each other as members of the community. Other factors noted by stakeholders included:

Good working relationships between Scottish Natural Heritage and the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency

A long-history of marine spatial planning

Having only one local authority

Good leadership from the SIMPP as a “neutral broker”

Fisheries and aquaculture stakeholders explained how there is good relationships between different sectors. The following factors were attributed to this:

A strict licensing regime for fisheries based on scientific understanding of sustainable fishing capacity.

Regulation of shellfish fisheries (creel limits)

Access for creel fishermen to cod quota enabling diversification (and port infrastructure to support this).

Organisations representing different fisheries sectors working in the same building alongside SNH.

Understanding of the need for sustainability.

Fisheries stakeholders spoke highly of the work of the NAFC (formerly the North Atlantic Fisheries College) Marine Centre in capturing the views of stakeholders.

Environmental stakeholders said that sensitive handling of fisheries data ensuring the ownership of fishermen has led to good collaboration on data projects.

Aquaculture stakeholders were concerned about a lack of action by SEPA on the impact of septic tanks on water quality of shellfish water protected areas (SWPAs). The Committee were told that 47 of 85 designated SWPAs in Shetland had been downgraded.

Marine Planners in the SIC said that SEPA was still “finding its feet” in its role in Regional Marine Planning. The Committee were also told that SEPA had a high caseload and limited resources. SEPA said that they needed more of a steer on its role and how it should be resourced.

Clyde

The main tensions in the Clyde were between mobile fisheries and environmental stakeholders. Many of these tensions relate to opposing views on what Regional Marine Planning should deliver which are discussed in Theme 2 above.

One environmental stakeholder said that Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups were not collegiate in involving other stakeholders in fisheries management. They also raised concerns over the impact of certain fisheries activities on the marine environment (listed in Theme 2 above).

Fisheries stakeholders said that some environmental organisations were more “extreme” than others and were difficult to work with. It also raised concern about some groups that appear to represent fisheries being funded by environmental charities. One stakeholder also questioned the sustainability of creel fishing because there is no limit on creel numbers in the Clyde.

Trust in scientific data

There were also tensions about the reliability and use of scientific data and the role of the Clyde 2020 Research Advisory Group (RAG).

One environmental stakeholder raised concern about the lack of peer-reviewed science and reliance on anecdotal evidence in the draft Clyde Marine Region Assessment. Its view was that mobile fisheries stakeholders dismiss scientific evidence that does not agree with the status quo and sought to attribute the decline of fish stock in the Clyde on climate change or a lack of fish feed

Fisheries stakeholders were concerned about bias in science conducted in collaboration with environmental organisations. It also explained that its request to have a fisherman with good working relationships with scientists to be included in the Clyde 2020 RAG had been rejected.

They also said they had trust in science conducted by Marine Scotland Science and indicated it would prefer that all science used in Regional Marine Planning would have the involvement of Marine Scotland.

Evening stakeholder event

Issues of transparency in the CMPP and community involvement in decision-making were raised at the stakeholder event. One attendee was concerned about the ability to feed into licensing decisions of Peel Ports saying that it felt like the Clyde “belongs to Peel Ports”. Its view was that members of the CMPP were only representing their own interests.

Orkney

In Orkney, some tensions between inshore fisheries and renewable energy industry stakeholders were discussed. The Committee heard from fisheries stakeholders and the OIC that early leasing decisions for renewable energy by the Crown Estate were approved without consultation with fisheries stakeholders.

One fisheries stakeholder said this led to a big effort for them to prove the industry’s worth. It also explained that the community value of fishing was more important than its monetary value.

It also said that the renewable energy industry demonstrated naivety and arrogance initially in not seeking local knowledge from fisheries and oil and gas experts on the siting of developments. This stakeholder's experience had coloured its perception of the forthcoming Marine Planning Partnership.

Renewable energy stakeholders acknowledged previous consenting and said they were now collaborating with fishers. They viewed the MPP as a vehicle for further collaboration. The industry was using local boats to access installation to improve social acceptance of the industry. Its view was that fishermen were not necessarily against developments in principle but are frustrated if they are not consulted and local knowledge is not sought.

The OIC said that there is pressure to grow the aquaculture industry in Orkney and referred to a “resistance to rock the boat” in objecting to expansion. It revealed that the Scottish Government had overturned a decision by the OIC to refuse consent for a fish farm development. However, OIC Councillors said that the initial refusal was due to public concern rather than compliance with statutory requirements.

THEME 4: Finance, resources and expertise

A lack of finance, resource and expertise was a recurring theme in all three visits. Stakeholders from all regions asked for clarity from the Scottish Government over funding for the following:

Staff and resources for Marine Planning Partnerships

Data collection and monitoring

Wider roll out of Regional Marine Planning

The availability of marine planning expertise varied. Shetland and Orkney had dedicated marine spatial planning teams embedded within Councils. There is a lack of marine spatial planning expertise in the Clyde.

Shetland

The SIC is well resourced for marine planning. It has a Coastal Zone Manager’s post and a dedicated marine planning team. The Council said that this expertise reflects its priorities based on the value of the marine economy to Shetland. Furthermore, the SIC has access to reserve funds through the Zetland County Council Act 1974. The SIC recognised that it would be difficult to replicate this investment in other regions without government funding.

The SIC were concerned over a lack of resource within Marine Scotland to support Regional Marine Planning. The SIC is active in accessing European funding to support its work and wanted clarity on replacement funding through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund.

Environmental stakeholders were concerned about the lack of available funds to deal with invasive and non-native species. One stakeholder highlighted the need for wider rollout of RMPs to protect migratory species such as seabirds.

Clyde

Environmental stakeholders expressed concerned over a lack of funding for science, data collection and monitoring and relied on using its own resources and volunteers and citizen science to monitor the South Arran MPA. They also said there was no government funding available for research and highlighted big data gaps for monitoring.

One stakeholder said it was aware that Councils in the Clyde region were short of finance and expertise in marine planning and expressed particular concern over expertise in relation to aquaculture.

At the Committee’s stakeholder event, it was suggested that there should be resources for dedicated marine planning staff to work between Local Authorities in the region.

A marine recreation stakeholder and staff of the CMPP highlighted the importance of monitoring. MPP staff wanted clarity over what long-term funding would be available to the CMPP after its Regional Marine Plan had been approved. This included funding for:

Staffing and running of the CMPP

Data collection and monitoring

Responding to licensing issues

Projects for monitoring of fisheries activities

Fisheries stakeholders were also concerned about potential gaps in marine planning regimes, such as the Solway Firth if RMPs were not rolled out in other Scottish marine regions. They were also concerned about transparency over how funds for outreach work were being spent by the CMPP.

Stakeholders were in general agreement that CMPP staff had worked well with the limited resources that were available to them.

Orkney

The OIC explained that delivering regional marine plans required a lot of skills and expertise. It informed the Committee that to deliver its regional marine plan it needed two full-time marine planners with environmental expertise to deliver the State of the Environment Assessment (SEA) report. The OIC said it has been given a £68K grant from the Scottish Government and is also using EMFF (European Maritime and Fisheries Fund) funding to support its SEA report.

The OIC indicated that the Western Isles Council are interested in forming an MPP but had no funding to bring it forward. It also questioned the feasibility of Regional Marine Planning for the Highlands Council which covers three marine regions but has no marine planning expertise available.

Following the Committee’s visit the OIC submitted the following comment in the online engagement platform:

“It is a large responsibility to take on a Delegate role as there needs to be an appropriate mechanism not only to prepare the Plan and its many supporting documents, but also the requirement to act as a statutory consultee of marine licences and capacity to respond to other consultation such as Crown Estate leases, MPA [Marine Protected Area]/SPA [Special Protection Areas]/SAC [Special Areas of Conservation] proposals etc".

Renewable energy industry stakeholders highlighted the importance of the industry for training a skilled workforce in Orkney and bringing international expertise to the Islands. This was important for keeping and attracting young people to Orkney.

Heriot-Watt provides a Masters in Renewable Energy and said that last year 9 of its 30 students stayed in Orkney after completing the course.

THEME 5: Community and stakeholder engagement

There were mixed views on how well communities and stakeholders had been engaged in the process of regional marine planning. In general, engagement appeared to have been better in Shetland and Orkney than in the Clyde. However, the geography and size of communities in Shetland and Orkney is likely to have an important influence on the effectiveness of engagement.

Shetland

The SIC has involved the community in Shetland through Community Councils. Consultations were also sent to organisations at a national level (NGOs). The SIC also spoke of the importance of expertise and local knowledge within the Shetland College

The college carried out pre-consultation work within communities. The SIC also said that academics involved in marine planning are also embedded within the community and have a local knowledge and understanding of how communities work.

The SICs Community Planning Partnership has also been developing the Shetland Partnership Delivery Plan which has helped to identify community needs to feed into regional marine planning

Clyde

The Committee heard from the CMPP staff that it has carried out a range of engagement activities. This included:

Public dialogue work and work with schools carried out (28 events held around the region)

Topic sheets on the environmental assessment report aimed at the public

A layman’s guide animation about the environmental assessment report

A non-statutory pre-consultation on the draft CRMP communicated through community councils

A public engagement project financed by £200k EMFF funding

Information published in local newspapers and on social media

CMPP staff said that communities that were most engaged had live issues in their areas (e.g. planning applications for fish farms). In its most recent consultation, the CMPP received 49 responses, around half of which were from members of the CMPP.

One stakeholder said that it was difficult to expect members of the public to provide views on around 500 pages of legal documentation that comprises a regional marine plan.

The amount of engagement conducted by the CMPP did not appear to translate to the level of awareness of some attendees at the Committee’s evening stakeholder event. Some attendees were disappointed by a lack of participation and representation and felt there was no voice for community councils in the process.

Others thought that Community Council Liaison Officers could be better utilised to involve communities in feeding into the CMPP for more of a bottom-up approach. There was distrust in councillors’ ability to represent the community and suggestion that there should be someone on the CMPP who represents the voice of community councils without having other vested interests.

Environmental stakeholders highlighted the importance of having communities in the Clyde engaged in the marine environment to take ownership of issues.

This view was exemplified in a comment posted in the Committee’s online engagement platform:

“A main challenge is how to get out to people in general that there is such a thing as regional marine plans. And even harder is for people to understand exactly what the purpose of the regional marine plan is. At the meeting in Troon on 24 November many attending were asking that very question - What is the purpose of the CMPP?"

Orkney

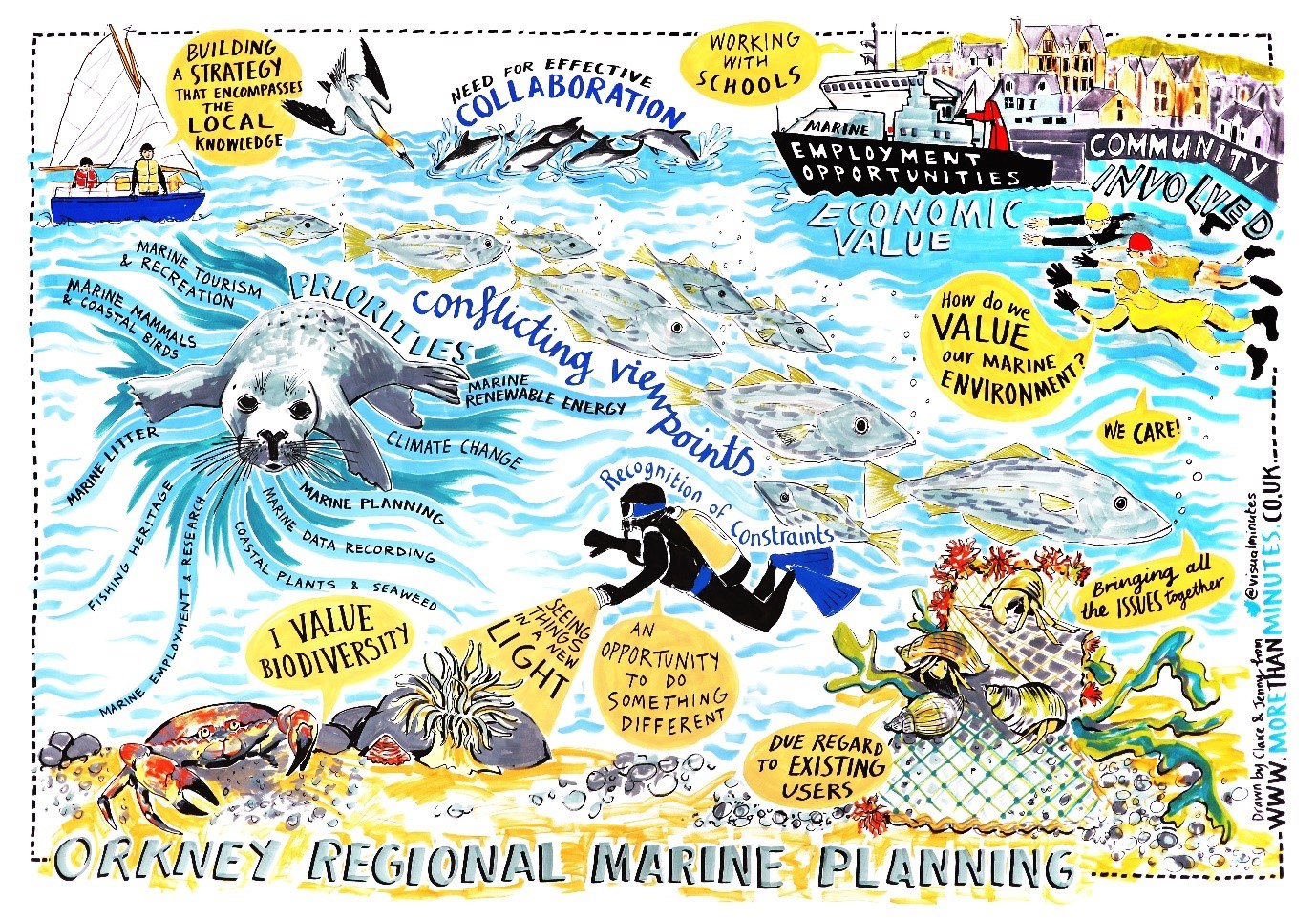

The OIC is in the early stages of developing its Regional Marine Plan. The OIC shared examples of visual minutes it had developed from community engagement activity on regional marine planning (see image below).

Visual minutes of community consultations conducted by the OIC Source: Orkney Islands Council

Source: Orkney Islands Council

The OIC submitted the following contribution to the Committee’s online engagement platform:

“[Engagement] needs to be adapted to the different types of audience you want to engage. Whilst open, public meetings can get good attendance if publicised well, there is a limit what one marine planning officer can do, so expectations need to be managed and limitations of capacity recognized […] Sufficient staff to undertake engagement effectively is therefore essential."

Heriot-Watt University told the Committee that consultations were carried out on the previous non-statutory Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters Marine Spatial Plan. It said that consultations were much better in Orkney compared to Thurso but that Councillors were much closer to their communities in Orkney compared to on the mainland.

Attendees at the Committee’s stakeholder event felt that there could be better communication of activities from the Council. There was a lack of awareness of the process of regional marine planning and how they could feed into the process.

Attendees also said that there was a wealth of local knowledge in the community that could be communicated but would not necessarily be aware of events held in Kirkwall. Therefore, there was a need for the Council to visit smaller islands to engage

Annex 1: List of organisations the Committee met

Shetland

Shetland Island Council (Marine Planners, Community Planning and development and Councillors)

NAFC Marine Centre (attended evening stakeholder event)

SNH

SEPA

Shetland Fishermen’s Association

Seafood Shetland

Shetland Mussels Ltd

Shetland Amenity Trust

RSPB

Visit Scotland

Clyde

Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST)

Clyde 2020 Research and Advisory Group

British Marine Scotland

Royal Yachting Association Scotland

Clyde Marine Planning Partnership staff

Clyde Fishermen’s Association

West Coast Regional Inshore Fisheries Group

Sustainable Inshore Fisheries Trust (SIFT)

RSPB

Orkney

Orkney Islands Council (Marine Planners and Councillors)

Orkney Harbour Authority

Orkney Fisheries Association

European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC)

The International Centre for Island Technology (ICIT), Heriot-Watt University

Aquatera Ltd.

Xodus

RSPB (attended evening stakeholder event)

Annex 2: Glossary or acronyms

CMPP – Clyde Marine Planning Partnership

CRMP - Clyde Regional Marine Plan

MSP – Marine Spatial Planning

MPP – Marine Planning Partnership

OIC – Orkney Islands Council

OIMPP – Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership

RMP – Regional Marine Plan

SIC – Shetland Islands Council

SIMPP – Shetland Islands Marine Planning Partnership

SIRMP – Shetland Islands Regional Marine Plan

SSMEI – Scottish Sustainable Marine Environment Initiative