Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee

Embedding Public Participation in the Work of the Parliament

Membership Changes

During the period covered by this report (February 2022 to September 2023), the Committee membership changed as follows:

Fergus Ewing was appointed on 31 March 2022 to replace Ruth Maguire

Carol Mochan was appointed on 19 January 2023 to replace Paul Sweeney

Foysol Choudhury was appointed on 25 April 2023 to replace Carol Mochan

Maurice Golden was appointed on 29 June 2023 to replace Alexander Stewart

Executive Summary

The Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee has spent over a year looking at how the public can engage with the Parliament. It has heard from experts and consulted people inside the Parliament and outside. It has looked at “citizens’ assemblies” run by the Scottish Government and learned about how they work in Ireland, Paris and Brussels.

The Committee set up its own “Citizens’ Panel” – a group of 19 people from across Scotland who were asked: “How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?” The Panel met over two weekends in late 2022, and came up with 17 recommendations.

The Cotmmittee has concluded that the Parliament should use Citizens’ Panels more regularly to help committees with scrutiny work. It accepts these panels are not suitable for every topic and can be expensive, but they give ordinary people a voice and can help achieve consensus on difficult issues.

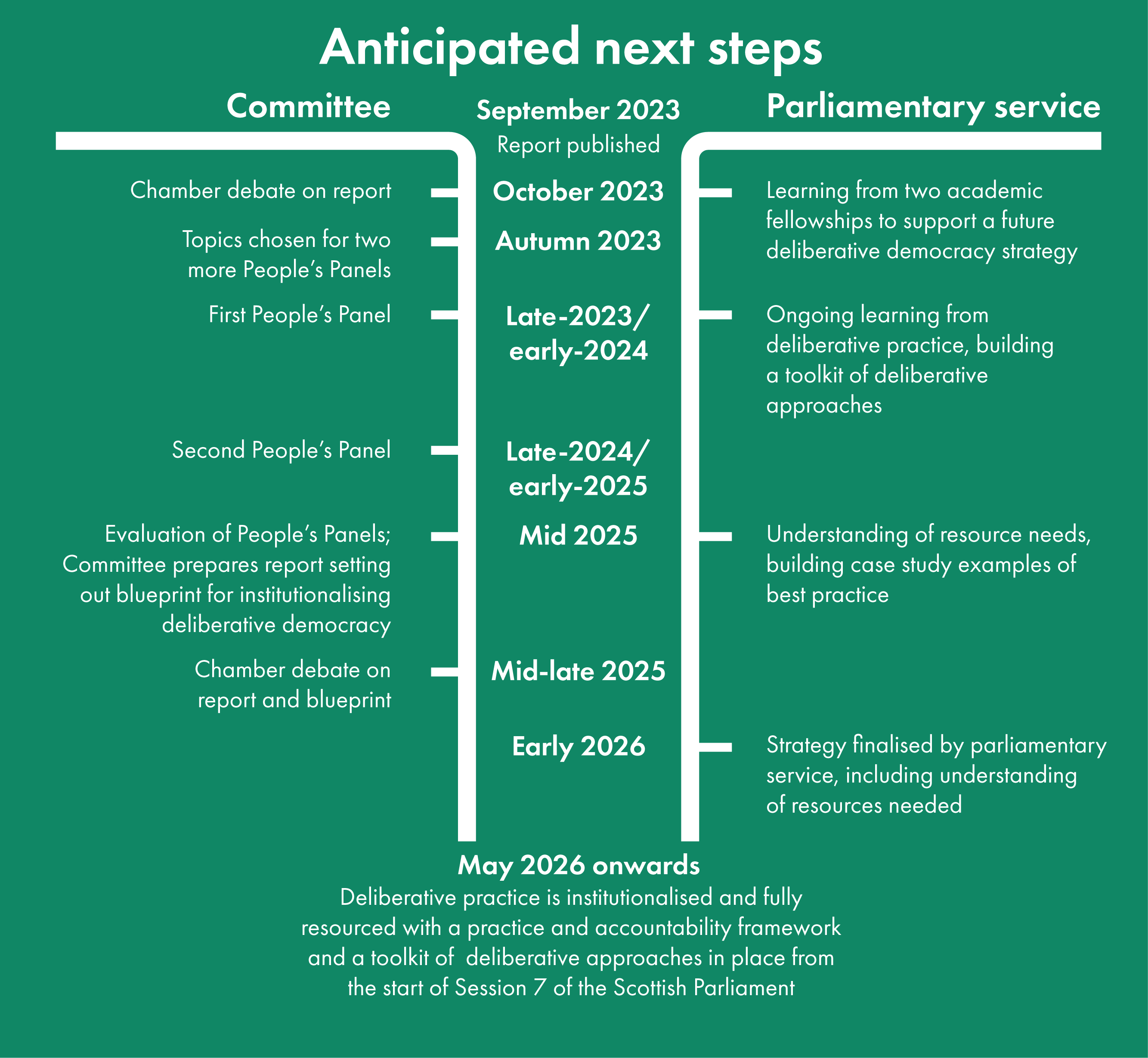

As a first step, the Committee wants the Parliament to run two further panels. One should review a piece of legislation that has been in effect for a few years, to see how well it is working. Another should look at a current topic of interest. The Committee expects to be involved in setting these Panels up, and then in reviewing how well they have worked. At the end of this process, it expects to recommend a model that the Parliament can use after the 2026 election.

The Committee has come up with some principles for the future use of “deliberative democracy” (including Citizens’ Panels). These include making sure the method used each time is in proportion to the topic, and that the Parliament is transparent about how it works. The people who take part should be given support, made to feel in control, and given feedback on how their ideas are taken forwards.

The Committee recommends setting up a separate Citizens’ Panel (or “people’s panel”) for each topic, rather than having the same panel looking at multiple topics. It suggests panels of about 20-30 people. It doesn't think panels should include MSPs – though it thinks that MSPs might be invited to join some of the discussions.

Panel members should be selected at random, with the aim of getting a group of people who reflect Scottish society. That means, for example, having an equal number of men and women, a range of ages and people with different levels of education. They should be given the support and information they need, and should be paid for taking part.

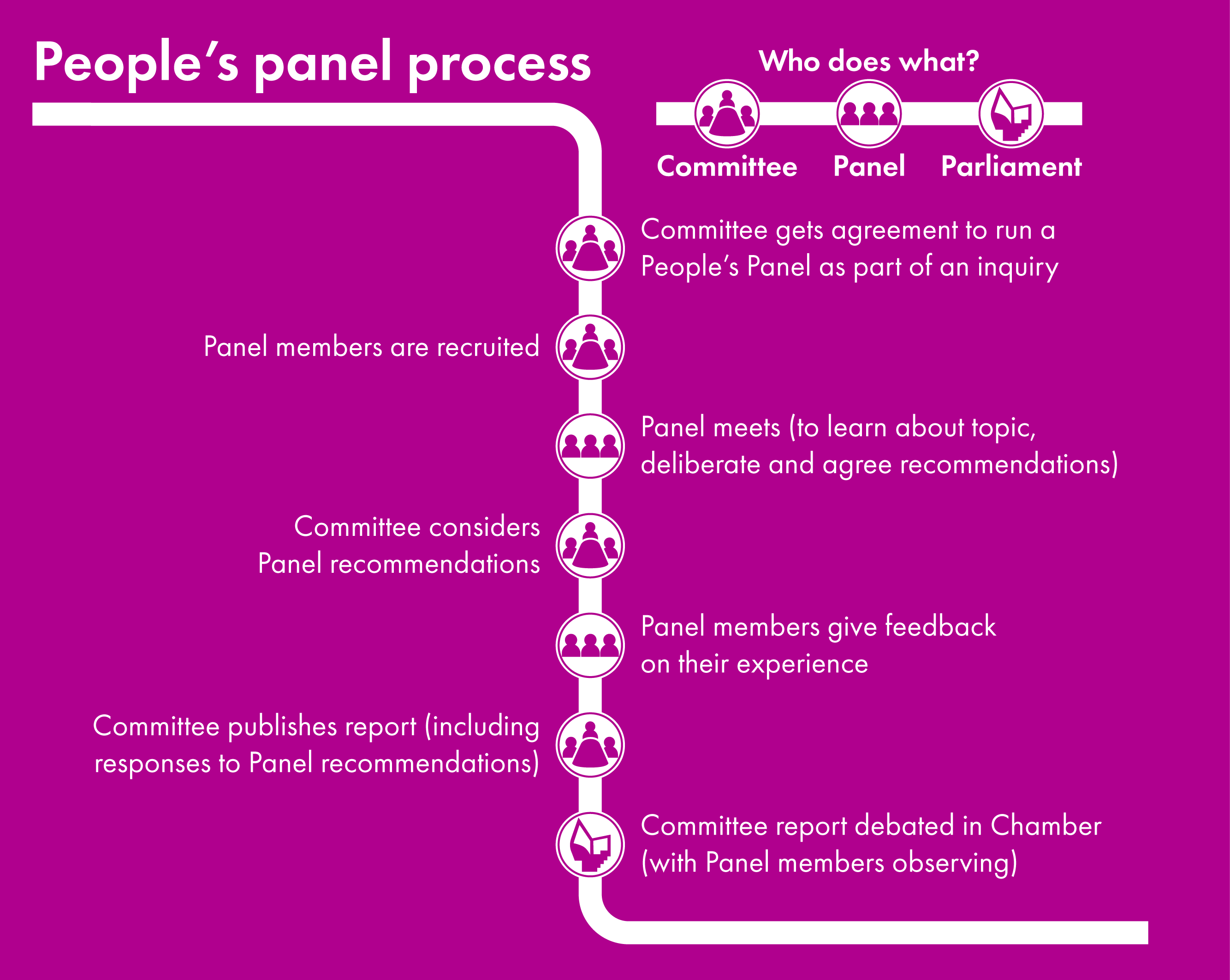

Each time a Panel is set up to help a committee with an inquiry, the committee’s report should be debated in the Parliament Chamber, with Panel members invited to watch from the public gallery.

As well as considering how future Citizens’ Panels might work, the Committee has considered other ways that people can find out what the Parliament is doing, and how to get involved. Some of the ideas it looked at came from the recommendations made by its own Citizens’ Panel.

The Committee agrees with the Panel about the need to reduce the barriers to participation. The Committee points to the work that Parliament staff are already doing, and recommends further things they should look at. These include:

paying people back if they have to take time off work or pay for childcare in order to engage

translating information into other languages, or making it easier to read

making it easier for people to engage in the evenings or at weekends, or by using online tools

considering a review of citizenship education in schools.

The Committee has also considered three recommendations (made by the Panel) for changes to how the Parliament works.

The first was to review the rules on MSPs’ behaviour. The Committee doesn’t recommend setting up a Citizens’ Panel to do this, but thinks it could be looked at by the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee, which already has a role in considering the conduct of MSPs.

The second suggestion was to give the Parliament’s Presiding Officer more power to make sure that Scottish Government Ministers give adequate answers to questions. The Committee recognises that this could make the Presiding Officer’s job more difficult and more political. But it also thinks that not answering questions properly is discourteous, shows a lack of respect and undermines public trust. So it suggests that this issue, too, is considered by the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee.

The third idea was to schedule time in the Chamber each week when members of the public would be able to ask Ministers questions. The Committee does not support this idea, but is willing for it to be looked at if there is support for it across the political parties.

Part 1: Introduction and background

At the start of Session 6, the name of the Public Petitions Committee was expanded to include Citizen Participation, and the following additional element was added to its remit: “to consider and report on public policy or undertake post-legislative scrutiny through the use of deliberative democracy, Citizens’ Assemblies or other forms of participative engagement”.

This reflected an increased focus on the use of deliberative engagement approaches in Session 5, following on from recommendations from the Commission on Parliamentary Reform in 2017, which included, among other things, the establishment of a Committee Engagement Unit (now the Participation and Communities Team, or PACT) with a particular remit to test mini-public and digital approaches to engagement.

The Committee agreed, in February 2022, to reflect its new remit by undertaking an inquiry which would consider how the Scottish Parliament should embed citizen participation (including deliberative engagement) as part of its work.

In March 2022, Committee members held an informal evidence session with experts in deliberative democracy and Parliamentary engagement to provide background information on issues surrounding deliberative democracy and public participation in the work of Parliaments.

Key Terms

| Key Terms |

|---|

| Citizens’ Assemblies or Citizens’ Panels – larger or smaller groups of people, selected to be broadly representative of the wider population, who are invited to consider a topic together and come up with recommendations |

| Deliberative democracy – methods (including Citizens’ Assemblies and Panels) that allow participants to contribute to policy-making by discussing a topic in a structured, open and informed way that encourages consensus |

| Public (or citizen) participation – any way in which members of the public can play an active part in the Parliament’s work |

| Participative democracy – the idea that participation by the public should be a routine part of how a Parliament considers issues and reaches decisions (as an alternative to a purely representative democracy) |

| Post-legislative scrutiny – scrutiny of a piece of legislation (e.g. an Act of the Scottish Parliament) after it has been in effect for a time, to consider how well it is working |

| Representative democracy – the traditional model in which elected members (such as MSPs) deliberate and make decisions as representatives of the public, with little or no direct involvement by the public themselves (other than at elections) |

Scottish Government

In summer 2021, the Scottish Government established a Working Group to make recommendations to Ministers on “institutionalising participatory and deliberative democracy” (IPDD). The Working Group reported in March 2022, and its recommendations included the following:

Consider the proposals of the Citizens’ Assembly on the Future of Scotland for new infrastructure associated with the Scottish Parliament, including a Citizens’ Chamber or Citizens’ Committee.

Collaborate with local government, public services and the Parliament to establish and agree clear agenda setting guidelines for all Citizens’ Assemblies.

Connect to the Scottish Parliament Committee system for scrutiny of Citizens’ Assembly processes and recommendations.

Parliamentary Service and Public Engagement Strategy

The SPCB’s Strategic Plan for session 6 includes strategic change objectives for developing a “dynamic, modern parliamentary democracy” and “new ways of working.” The Plan includes a commitment to “embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Parliament.”

The Public Engagement Strategy agreed by the SPCB in 2021 has as its primary aims to:

increase the reach of the Parliament’s engagement and the diversity of those engaging with us;

improve the knowledge and confidence of people to engage with us and with the democratic process; and

improve the Parliament’s reputation as a relevant and trusted institution.

This is a long-term strategy, building on the existing engagement work undertaken by teams across the Parliament. To ensure sustained and meaningful change, a programme of focussed activities is being delivered incrementally through annually updated delivery plans.

The Citizens' Panel on participation

The Committee agreed at its meeting on 1 December 2021 that a Citizens’ Panel – a diverse group of members of the public – should be established to support the Committee's inquiry into public participation.

Preparatory work

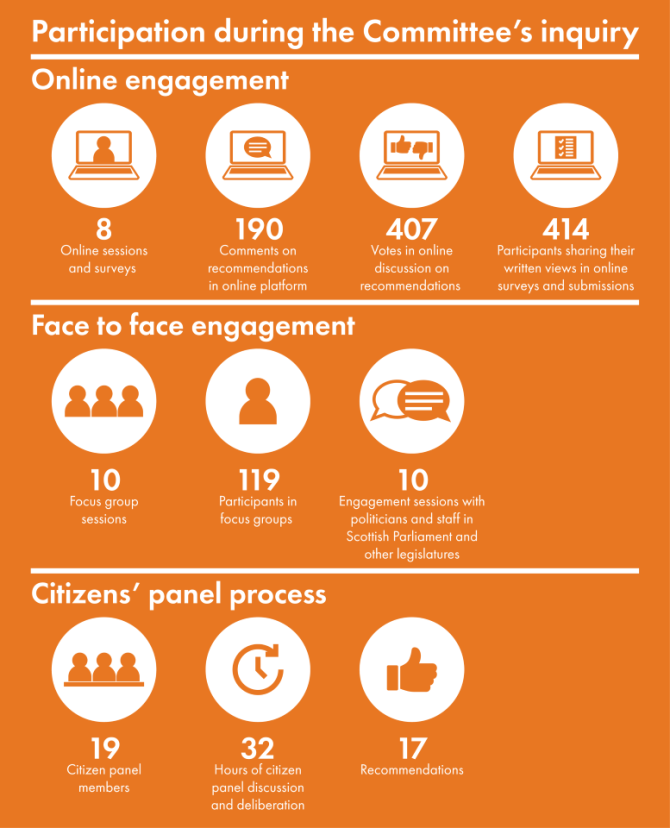

Engagement activity and evidence gathering was carried out from March to July 2022 and helped to inform the issues and topics considered as part of the Citizens’ Panel. This included a short public survey that received 305 responses from members of the public across Scotland, and a longer survey seeking more detail on increasing engagement, which had responses from 35 organisations and individuals, including academics. We followed this up with 10 focus groups with various under-represented groups, including those from minority ethnic backgrounds, those living on a low income, and those with physical and learning disabilities.

Some of the themes that emerged from this evidence were:

that people from disadvantaged backgrounds often don’t feel that engaging with the Scottish Parliament is worthwhile

that education is vital if barriers to participation are to be broken down, so that there can be more diversity in the opinions that shape the work of the Parliament

that cross-party groups play an important role in involving people from minority groups and with protected characteristicsi

that the Parliament needs to do more to tell people about its engagement and participation work

that strengthening trust in politics and politicians is essential if the Parliament is to be successful in involving people in its work.

Numerous barriers to engagement were identified, including:

money – which was linked to level of education, employment status, time and age

time – people who are very busy need to feel that taking part is a worthwhile use of their time

education – people need to understand what the Parliament does, including by learning about it at school, in order to see how they can contribute

trust – people don’t feel heard or represented, so have lost trust in politics and politicians; that trust needs to be regained to give people an incentive to engage

fear – people need to feel safe and not at risk of intimidation before they will take part; many are not comfortable in a formal environment

representation – people are more likely to engage if they see that others from similar backgrounds or in their own age-group are already involved.

People felt that more resource was needed to overcome these barriers and help people engage with the Parliament’s work. This could involve more resource for education providers, support services and voluntary organisations to facilitate public engagement. It could also mean increased funding within the Parliament, for example to allow it to reimburse people for the costs they incur by engaging.

Steering Group and external evaluation

The Parliament’s Citizens’ Panel model involves the appointment of an expert Steering Group to support the process. The role of the Steering Group is to help ensure that the process is conducted fairly, credibly and transparently. The Steering Group’s first task was to agree an overarching question for the Panel to consider, which was: “How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?”. The Steering Group also provided oversight of the work done by PACT on the design of the sessions, the topics being discussed, and the expert witnesses invited to present on each topicii.

Another element of the model is the appointment of an independent external evaluator – in this case Professor Sabina Siebert of Glasgow University. She observed in-person and online sessions of the Panel and interviewed staff and participants to inform an interim report that was provided to the Committee in December 2022. Professor Siebert’s final report, which includes an analysis of how the Panel’s work has contributed to the inquiry outcomes, is published alongside this report.

Selection of participants

PACT worked with the Sortition Foundation (a third sector organisation with expertise in this kind of recruitment) to recruit a randomly selected and stratified sample of people, based on Scottish Census data. The first step was to send invitation letters in August 2022 to 4,800 randomly-selected residential households across Scotland. Respondents were asked to provide information about their gender, age, ethnicity, disability, educational attainment level and postcode, and this was used to select from the 159 responses a sample of 24 people broadly representative of the Scottish population. Unfortunately, after it was necessary to reschedule following the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, changes in people’s circumstances (such as unexpected caring responsibilities and illness) meant that some selected participants had to drop out. This resulted in a final Panel of 19.

Participants had their travel and accommodation costs covered and received a participation fee of £330 in recognition of their time and commitment. Participants were also offered any IT equipment they needed to take part, and were given training and guidance in the use of relevant software.

.png)

Working methods

Panel participants worked together for over 32 hours over two weekends and three remote online sessions in October and November 2022.

As part of the Panel process, participants:

were involved in team building

learned about the Scottish Parliament and about participation and deliberative democracy, and

were coached on questioning witnesses, deliberation and consensus-based decision-making.

Participants heard evidence from:

Scottish Parliament staff

MSPs

members of the public who have experienced barriers to participation

political scientists and academics

deliberative and participative democracy practitioners

people who had taken part in previous citizens’ panels run by the Parliament

journalists, and

a wide range of community organisations.

During the various Panel sessions, participants:

worked in small groups to explore the evidence and express their opinions in a relaxed environment;

had opportunities to reflect on the evidence they had heard before discussing issues and making decisions with the wider group;

contributed to the design of the second weekend, including by suggesting witnesses they wanted to hear from; and

used an online platform to reflect on the information provided, pose questions and identify potential recommendations.

Facilitators helped ensure that participants worked in various groups and were exposed to a range of views, including by ensuring that, as far as possible, each breakout space was balanced in terms of gender and age.

Panel report and recommendations

By the end of the deliberative process, the Panel had agreed on seventeen recommendations to improve how the Parliament engages with the people of Scotland, grouped under four headings:

Community engagement

How the Parliament uses Deliberative Democracy

Public involvement in Parliamentary business

Communication and education

The Citizens’ Panel report was published as an annex to the Committee’s interim report on 16 December 2022. In preparation, the Committee heard evidence from some of the Panel members on 14 December 2022. We were very encouraged to hear their positive responses to being involved. For example, Ronnie Paterson said:

"I absolutely loved the process that we were involved in."

while Gillian Ruane said:

"I loved the whole experience from start to finish."

One of the benefits to being involved was learning more about how the Parliament works. Paul MacDonald said:

"I have always been a follower of politics, but I did not even know the difference between Parliament and Government when I started the process – I did not understand the separation in the structure."

John Sultman commented favourably on the information presented to the panel, saying:

"Some of that information confirmed things that I thought I knew, and other information completely dispelled illusions that I had."

Panellists also enjoyed the ability to collaborate as a group. Maria Schwarz said:

"The panel was a great opportunity to come together. A lot of people had their own ideas to contribute, which we could expand on to come up with even better plans."

Ronnie Paterson told us:

"As an exercise, it has been a great success to bring forward our recommendations as a group. Doing that together as a random group of people has been amazing, and I would love to see that happening again, whether that is on a national level or at the level of a local issue."

In her interim report, Professor Siebert (the external evaluator) said that the selection of witnesses presented to the panel was excellent and that information was presented in a robust and balanced way. She praised the planning, facilitation, materials and running of the events, the delivery team’s inclusive approach and culture of continuous improvement, and the positive impact on participants. She did, however, note minor challenges around recruitment, evidence provision and resourcing.

Further engagement work

Since the publication of the interim report, the Committee has carried out further engagement and consultation on the Panel’s recommendations, by means of:

an 8-week online public consultation to help prioritise the Panel’s recommendations, supported by outreach sessions with young people and people with learning disabilities and autismi.

internal consultation with MSPs and their staff, and with Parliament staff, on how recommendations might be progressed, taking account of current and previous engagement activities

a visit to the Houses of the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament) in Dublin in February 2023 to learn about Citizens’ Assemblies there from politicians, Citizens’ Assembly staff and former participants

a visit to Paris in March 2023 to learn about the Assemblée citoyenne de Paris (a Citizens’ Assembly linked to Paris city council) from participants, staff, advisers and elected council officials, alongside an additional meeting with deliberative democracy practitioners from Paris and Brussels

an online meeting with Magali Plovie, President of the French-speaking Parliament of Brussels, to learn about its “deliberative committee” model.

Acknowledgements

The Committee would like to record its grateful thanks to all those who have contributed to the inquiry so far. This includes the participants in the Citizens’ Panel, those who contributed to or supported our fact-finding visits, focus groups and consultations, those who provided evidence and the Parliamentary staff who have supported our work.

Seven themes for consideration

For the purposes of this report, we have regrouped the Panel’s 17 recommendations into the following seven themes:

Theme 1: Institutionalising deliberative democracy

Theme 2: Growing community engagement

Theme 3: Raising awareness of the Scottish Parliament

Theme 4: Improving the consultation process

Theme 5: Bringing the Parliament to the people

Theme 6: Education

Theme 7: Strengthening trust in the Parliament.

Part 2 of the Report covers the first of these themes, given that it is probably the most complex, and the one that most closely engages the Committee’s remit. It sets out the Committee’s vision for the future use of deliberative democracy in Scotland – in particular, the use of people’s panels by the Scottish Government and by the Parliament itself.

The other six themes are covered in Part 3. In these two Parts, we give our response to all 17 of the Citizens’ Panel’s recommendations.

Part 2: Institutionalising deliberative democracy

Citizens’ Panel recommendations

We have grouped under this theme (Theme 1) the following three recommendations by the Citizens’ Panel:

7. Legislate for Deliberative Democracy in order to ensure that:

diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence Scottish Parliament’s work, and

the public are consistently informed and consulted on local and national issues.

In drawing up this legislation the Parliament should:

Recognise that there is not one engagement solution that fits all situations and issues.

Design and implement a framework based on this panel’s recommendations for ensuring diverse participation in deliberative democracy.

The framework should include:

An annually recurring citizens’ panel with agenda-setting powers to determine which local and national issues require either national or local people's panels (e.g. ‘deliberative town halls’).

Protection for participants to improve participation. We do not agree that participation in panels should be mandatory, but protective elements such as the right to time off work should be included for people who are selected to take part.

Rules around how MSPs consider and respond to recommendations from people’s panels such as mandatory follow-up to people’s panels’ recommendations no later than 9 months and a response from the Parliament and Government.

Potential for mixed MSP–people panels.

Ability to form local panels with local MSPs with outcomes that are sent up to the national level.

8. Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact.

9. Build cross-party support for deliberative democracy as this is needed for it to work

Context: progress to date

When the Parliament’s Participation and Communities Team (PACT) was set up, one of its purposes was to test the potential of deliberative democracy to enhance scrutiny. Four citizens’ panels have now been run using different locations and formats, three of which were independently evaluated and one internally. These evaluations have shown that, when these panels are integrated effectively with the aims of an inquiry, they can make a meaningful contribution to scrutiny and, at least in the short term, can enhance participants’ view of the Parliament and their confidence to engage in politics in future.

The Scottish National Party committed to running citizens’ assemblies in its 2021 manifesto and the Scottish Government has so far run two – the Citizens Assembly of Scotland and Scotland’s Climate Assembly – and has announced its intention to run further assemblies on local government funding and on drugs policy, as well as a young people’s assembly, although no firm timescales have been announced.

The Scottish Government’s Institutionalising Participatory and Deliberative Democracy (IPDD) working group set out extensive recommendations for ways of using deliberative democracy effectively in central and local government and in the Parliament. The Scottish Government published its response to theIPDD working group report on 27 March 2023.

In June, SPICe launched two academic fellowships on public participation, which should report in late 2023. The aim is to build on existing academic research (and the Committee’s information gathering) in order to generate recommendations on core principles for deliberative processes, and a framework for measuring impact that could work in a Scottish Parliament context. This could include consideration of how to make the most of deliberative approaches in a scrutiny setting, and how this differs from practice in a policy development setting (which would contribute to addressing the Panel’s recommendation 8).

Views gathered

In the recent public consultation, Recommendation 7 on legislating for deliberative democracy was the most prioritised recommendation. There was support for using citizens’ assemblies more to inform the work of the Parliament, and one specific suggestion was that this was a positive way to link to rural communities. A legislative framework was seen as a way of ensuring the recommendations were acted upon. There was an emphasis on understanding how to achieve a high-quality process, and suggestions that building an evidence-base would help gain cross-party support (which is seen as crucial to success). Concerns were also expressed – including that deliberative democracy could be expensive and could be at odds with the representative role of MSPs, and that a legislative framework shouldn’t be necessary.

The Conveners Group agreed that there was value in building the evidence base and highlighted the potentially off-putting language around deliberative democracy. MSPs expressed interest in how deliberative democracy works and supported the recommendation for building cross-party understanding of how it could be used in the Scottish Parliament.

Evidence from Dublin, Paris and Brussels

During its fact-finding visits to Dublin and Paris, and the Zoom meeting with Brussels, members heard views on the key choices that need to be made in designing a model of deliberative democracy.

Composition of panels

Brussels uses mixed panels consisting of both elected members and citizens, whereas Paris and the current Irish model are citizens only (Ireland initially used mixed panels). Each approach has pros and cons, with the balance between them dependent on cultural considerations specific to the country or legislature concerned. Both the Paris and Dublin meetings highlighted the potential for administrations to use citizens’ assemblies to legitimise and progress challenging policy. According to Magali Plovie, part of the reason for using mixed panels in Brussels was MPs’ reluctance to sign up to recommendations they had not had a part in developing.

Flexibility of approach

In Brussels, all the examples of using deliberative committees have tended to follow the same model as the first one, but the approach is continuously monitored and potential disadvantages to using a one-size-fits-all model are openly acknowledged. In Paris the aim is for each assembly to improve on the one before, and participation experts agreed that there are benefits to taking an iterative approach that is not too rigid. Participants in the first Assemblée identified during their final plenary session several improvements that could be made in the next iteration.

Choice of topics

Choosing topics can be challenging, and there are pros and cons when looking at bottom-up and top-down models. A bottom-up approach puts the emphasis on giving citizens autonomy, understanding and education on a topic, while a more top-down approach helps ensure topics are clear, relevant, measurable and within the competence of the executive that is expected to implement them. In Belgium, although some are suggested by the Parliament, topics can also be suggested by citizens using a petitions model. In Paris the experience was that citizens wanted to be given more direction on topics to explore and be supported to understand where the competence of the city council lay.

Legitimacy and participant buy-in

There are mixed views politically on the different ways of giving a citizens’ assembly legitimacy. The Irish model is mostly driven by demand, with topics identified in election manifestos as suitable for citizens’ assemblies. Using topics and mandates where a panel can have tangible influence gives the process legitimacy, and there are examples of sceptical elected members becoming positive about the process. In Brussels, the mixed member/citizen panel approach was seen to soften party divides, and there was a clear emphasis on the fact that while citizens’ votes help shape the outcome, the final decision rests with elected members.

Minimising participant drop-off and getting journalists more engaged to help spread knowledge were both issues raised. Potential solutions included getting to the deliberative stage promptly, increasing resources to engage with and support participants, adjusting the timing of events and providing more education on the panel process. The importance of participants knowing why they were there, and having a clear purpose for deliberative models, was emphasised by both practitioners and participants, and the personal and community benefits were praised by participants in Paris and Ireland. There was also an emphasis, in all the models we observed, on transparency in the deliberative process: that is, enabling non-participants to see how decisions had been reached (as well as how participants had been recruited, selected and educated on the topics at hand).

Parliamentary and executive models

No model the Committee observed originated within a Parliament. The Brussels approach came from public demand initially but has been formally established by the executive. The Paris and Ireland models both originated at an executive level, although in Paris a series of deliberative exercises preceded the Assemblée’s establishment by the Council, and in Ireland there is a clear Parliamentary path for assembly recommendations. Civil society practitioners said that it was important to recognise that the Scottish Parliament is the heart of Scottish democracy, and that deliberative democracy could open up opportunities for different levels of government to work together. They felt there should be a focus on the positive role of the Parliament for improving democracy and building better policy.

Resource implications

Currently, PACT has a budget for deliberative engagement of around £50,000 per year, within which it would be possible to meet the cost of one panel of around 20 people meeting over two weekends at the Scottish Parliament. The main costs of such an exercise would be participant recruitment costs, participant travel, food, hotels, remuneration for taking part, and staff overtime. The cost to the Parliament is likely to be less than the cost of an equivalent panel to the Scottish Government, as the Parliament can use its own staff and building, rather than having to hire a venue or contract with external suppliers. If the Parliament wished to support a more ambitious panel, with more participants and a longer timescale, its costs would scale up proportionately, and there would also be a cost in recruiting additional facilitators.

Larger assemblies of 80-100 (the scale likely to be needed to give credibility on more substantial issues) have generally met over several weekends. The Irish assemblies are estimated to cost €100,000 per weekend, while the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland cost close to £1 million in total1. The Canadian Government has set an intention of allocating 5% of its spending on elections to fund citizens’ assemblies. The costs of the Paris Assemblée largely consist of remuneration for participants and secretariat staff.

The external evaluation of the Citizen’s Panel on Participation showed that the in-house delivery was highly effective but impacted on staff in terms of workload in the run-up to and during delivery of events. If the Scottish Parliament were to scale up its activity in this area, it would need to consider how this would be resourced and supported alongside other participation work.

Committee conclusions

We have learned enough from this inquiry to be confident in recommending that the Parliament commit itself to further embedding deliberative democracy within its scrutiny function.

We also recognise the significant work and commitment shown by the Scottish Government in exploring the potential of deliberative democracy, in particular through the citizens’ panels it has already constituted and through the work done by its Institutionalising Participatory and Deliberative Democracy (IPDD) working group. We support the Government in this work, believing it can use deliberative democracy to address some of the big issues facing the whole country, including at a scale that is beyond the means available to the Parliament. It is clear from what we have learned that executive-led initiatives are well-established in other countries, and have often delivered worthwhile results, and we would not wish to see Scotland falling behind.

Each of the models we studied in Ireland, Paris and Brussels impressed us in particular ways, but each also had its drawbacks and limitations. We were also struck by the extent to which each was shaped by local politics and priorities. Perhaps the single most important lesson from our visits was that there is no ideal model to copy, and that both the Scottish Government and the Parliament should take time to develop their own models that are adapted to Scotland’s needs and circumstances.

Whatever model is adopted needs to be flexible. Different approaches will be needed according to how complex and controversial the topic is, the timescales and the political context. Cost is also a key factor: large-scale exercises in participative democracy could be extremely valuable for building consensus on the most difficult issues, but the substantial costs involved mean they could be justified only occasionally, for the right topics and where the Panel recommendations can have impact; for other, more routine issues, a simpler and quicker approach would secure far better value.

At this stage, it is not our aim to recommend a final model for the Parliament to adopt, but rather to encourage the Parliament to take the next few steps on what is likely to be a longer journey. We don’t yet know what the destination will look like, but we sketch out in the remainder of this section (paragraphs 55 to 93) a general direction of travel.

One starting point is that, in a Parliamentary context, participative and deliberative democracy are tools for enhancing scrutiny, rather than – as in an executive-led context – for developing policy. As a result, many of the obvious topics will already have been determined by the Scottish Government’s policy choices, and timescales may be tighter, particularly if the option is to use participative democracy as part of a legislative scrutiny process.

Principles

Our view is that scrutiny and representative democracy can be supported and enhanced through the innovative and flexible use of deliberative models. We recommend that this is guided by overarching principles in a way that is inclusive, appropriate, proportionate and effective, rather than built on fixed structures at this stage. By focusing on this approach, the Committee believes that MSPs from all parties, as well as the Scottish public, will be able to understand and trust in the use of deliberative democracy and support its role in the Scottish Parliament, at the heart of Scottish democracy.

Although the future shape of the Parliament’s deliberative democracy model will continue to evolve, we think it is possible at this stage to commit to certain core principles that should guide the process of developing that model. These are:

That deliberative democracy should complementthe existing model of representative democracy and be used to support the scrutiny process.

That the way in which deliberative methods are used, from recruitment through to reporting and feedback, should be transparent and subject to a governance and accountability framework.

That the deliberative methods used should be proportionate and relevant to the topic, and the scrutiny context.

That participants in deliberative democracy should be supported, empowered and given feedback on how their recommendations are used.

Process and timescale

Our aim for this report is to encourage the Parliament to embark on a journey, over the remainder of the current session, towards embedding deliberative democracy in its scrutiny work.

To achieve this, we recommend adopting a framework approach, in which a system of governance and accountability is used to support the delivery of different models of deliberative activity. The main advantage of such a framework approach is that it avoids the need to be prescriptive at an early stage about any particular model of deliberative democracy, while providing space and a structure within which various models can be tried and then evaluated, thus allowing for continuous improvement and innovation.

The main elements of this framework are already in place. The Parliament has a Public Engagement Strategy, supported by a Public Engagement Group and an agreed budget for the remainder of the session. Equally importantly, it has the benefit of an established in-house resource, the Participation and Communities Team (PACT), with over five years’ experience and strong relationships with external experts to draw on.

We also see an ongoing oversight role for this Committee, at least for the remainder of this session, reflecting the additional element that has been added to our remit. We believe we are well-equipped for this task, both because of what we have learned from this inquiry, and from our experience of considering the wide range of issues raised by public petitions, which span the remits of the Parliament’s subject committees. We anticipate working jointly with those committees, and with the Conveners Group, in identifying topics that would lend themselves to the experimental use of deliberative democracy, and then in evaluating the results of those experiments.

Specifically, we recommend running two further citizens’ panels – or, to use the terminology recommended by our own Panel, “people’s panels” – during the period up to early/mid-2025. That should leave time for the lessons learned to be fed into a further report that we expect to publish and have debated by mid/late 2025 – a report that, if it is endorsed by MSPs generally, can provide the blueprint for the Parliament’s use of deliberative democracy from the beginning of Session 7 onwards.

We recommend that one of those panels should contribute to a piece of post-legislative scrutiny – that is, a review of how well an Act of the Scottish Parliament (or specific parts of it), together with associated subordinate legislation and guidance, has worked in practice, whether it has achieved what it set out to achieve, and whether it has proved to be good value for money. One reason for suggesting this is that, while the Parliament has often expressed a commitment to the principle of post-legislative scrutiny, it has been less effective at actually carrying it out. Promoting post-legislative scrutiny is also one of the Conveners Group’s Session 6 priorities.

In making this recommendation, we recognise the importance of choosing the right Act of the Parliament to review. Some Acts lend themselves more than others to post-legislative scrutiny, and of those only some are likely to be on topics that would be suitable for consideration by a people’s panel. For example, it would have to be legislation with wide application and a direct impact on the lives of ordinary people, and where success could be evaluated without too much specialised knowledge.

To make this work, it would be important to secure the cooperation of the Scottish Government from the outset, including a willingness on the part of Ministers to give evidence to the panel if invited to do so.

For the second panel, we recommend a topic of general interest – that is to say, any substantial topic that a subject committee is already interested in inquiring into and that is not too partisan in nature. We would envisage consulting among the subject committees, perhaps through the Conveners Group, to identify something suitable.

We recognise that people’s panels are relatively expensive tools of scrutiny that take time to set up and to generate outcomes, so are only suitable for occasional rather than routine use and in situations where scrutiny is not subject to tight timescales. They are also unlikely to be appropriate for scrutiny of specialised topics, where it would be necessary to give panel members extensive training or induction in the subject-matter before they were equipped to grapple directly with the policy choices.

With both the panels we recommend, we would hope to secure agreement on the topics fairly promptly after publication of this report, to ensure there is adequate lead-in time.

Types of panel

Perhaps the most ambitious approach to participative democracy involves the establishment of a standing citizens’ panel – that is, a large panel that persists over time, though with each participant serving only for a year or two, so it is constantly available for consideration of a range of topics, likely supported by its own permanent secretariat. Given its scale and cost, this is not a model we currently recommend.

It is not difficult to see how a standing panel could be given a power of initiative – in other words, the ability to choose its own topics. But our preference is to do things the other way around, namely to identify topics of inquiry that could benefit from the input of a citizens’ panel, and then to constitute ad hoc panels tailored to each topic (in terms of size, composition and timescale). We consider this the better approach both for the Scottish Government, and for the Parliament, as it avoids blurring important lines of accountability and preserves democratic accountability (and so protects the interests of unelected panel members and elected politicians alike).

With Government-initiated panels, we recommend that aspiring parties of government identify suitable topics in advance and include them in election manifestos. That gives any panel that is established a clear democratic mandate for its role, and helps avoid any perception that politicians are passing responsibility for difficult political decisions on to the public – in other words, setting up a panel in order to push through changes that they would be reluctant to promote directly.

In the Parliamentary context, we are confident that the use of ad hoc panels can retain the benefits of continuity, since PACT will always be there to provide support to individual panels, learning from each one, in much the same way as a permanent secretariat supporting a standing panel. Shorter-duration ad hoc panels are also likely to minimise the problems of participant drop-off that we heard about in Ireland and Paris, and would help to give participants a clear understanding of their role and the time commitment needed.

Panel size and composition

Another important consideration is the appropriate size for a panel. In principle, a wide range of sizes would be possible, from mini-publics of around 10-20 people up to panels of 100 or more. For the Scottish Government, we can see real advantages in using a larger panel of up to 100, particularly if it is to tackle a more complex or high-profile topic. For the Parliament, however, we recommend smaller panels of perhaps 20-30, not least on grounds of cost.

A related question is whether to use citizen-only panels or mixed panels that include a proportion of elected members – such as the deliberative committees in Brussels that we learned about, which are made up of 45 citizens and 15 politicians.

Our clear preference is for the Parliament to use panels that are citizen-only in composition. The main reason for this is, again, to avoid a blurring of accountability and to ensure that deliberative democracy complements, rather than compromises, the established representative democracy model on which the Parliament is founded. We also see a risk that citizen members would feel intimidated by the presence of politicians around the table, or that the politicians would dominate discussions. A mixed panel might also compromise the perception that the panel is there as the voice of ordinary people.

Although we don’t think MSPs should themselves be members of panels, we do recognise that giving them some means of being directly involved in the workings of a panel could have some advantages. In particular, it could help to ensure that any recommendations are informed by political realities, making it more likely that they can be endorsed by the Parliament as a whole. It could also give MSPs more of an insight into how ordinary people view the issues that they must then decide on.

We therefore recommend routinely involving MSPs in some limited way, perhaps by inviting them to sit in on a plenary discussion at a suitable mid-way point – that is, after the initial phase of team building and information gathering, but before any recommendations have been finalised. This would allow panel members to share their emerging views with MSPs and get some initial feedback, while giving MSPs an early insight into the panel’s direction of travel – without diluting the sense that it is the citizens alone who generate the panel’s final recommendations.

Participant selection

A key aim of participative democracy is to bring decision-making closer to the people. This is based partly on a recognition that, despite the wide range of political views across the Chamber, MSPs as a group are not always representative of wider society – for example, they are more likely to be male, older and more educated. In addition, there can be a tendency for attitudes within the “Holyrood bubble” to become out of step with the views of ordinary people across the country. This disconnect is rarely challenged by traditional methods of scrutiny, which rely heavily on formalised evidence-sessions with invited experts, whose own demographic mix may be little different from that of MSPs. One of the potential benefits of deliberative democracy, therefore, is that it brings into the heart of the process those who live outside the bubble and who can examine the options more directly from the perspective of those who will be directly affected. This can be a form of “reality check” that helps avoid some of the problems that arise when policies shaped within political institutions prove unpopular or difficult to implement in practice.

Accordingly, any credible model for deliberative democracy has to start with a robust process for selecting participants who will operate as a microcosm of wider Scottish society.

This is not a straightforward thing to achieve. Each person is an individual and no-one can be reduced simply to a list of categories. In any case, there are too many different demographic factors to allow any panel, particularly at the smaller end of the scale, to be fully representative in every respect. Choices must always be made, with different demographic factors being given more weight according to their relevance to the topic.

We recommend that the main priorities for constituting a representative panel of any size should be:

a near-equal mixture of men and women

a range of ages (with 16 as the minimum age for participation)

a mixture according to income, employment status (including non-working and retired people) and/or level of education

a reasonable geographical spread, covering not just the main regions of Scotland in rough proportion to population distribution, but also a mixture of those living in cities or towns and those in smaller communities or rural areas.

Other variables that might be added in according to the nature of the topic, particularly with larger panels, include:

race/ethnicity and/or religion or faith affiliation (including people of no religion or faith)

health and disability

marital status and/or caring responsibilities.

In this context, we acknowledge the case for sometimes deliberately over-representing smaller minority groups, particularly where exact proportionality on a smaller panel might mean having only one panel member from that minority.

Process is also important, not just as a means of generating a representative panel reasonably efficiently, but also to do so in a way that secures the confidence both of those selected and the public more generally.

Established best practice is to do this broadly as follows:

Once the topic has been decided, the key demographic variables are identified. The target size of the panel is also specified.

A third-party organisation uses a random process to select, from the electoral register or a database of postal addresses, an initial number of households to be sent invitation letters. The letters explain the purpose of the panel and invite over-16s living at that address to apply, including by filling out a questionnaire that includes the chosen demographic variables.

The organisation then uses the demographic information provided by those who respond (the volunteers) to select non-randomly the target number of panellists. At this stage, the aim is to correct for any distortions that have crept in as a result of self-selection from the original cohort of invitees (such as that retired people may be more likely to volunteer than people of working age), and to anticipate where drop-out rates are likely to be higher (for example, by over-sampling younger participants or those with caring responsibilities).

The use of a third-party organisation and the random nature of the initial selection provides objectivity and limits the scope for any interest group to seek to influence the process. The outcome should be a panel that is as close to representative of wider society as is reasonably possible.

In this connection, we support the principle (applied to our own Citizens’ Panel) that the Parliament should, in addition to paying participants’ travel and accommodation costs, offer them a reasonable payment for their participation, in recognition of the time and commitment involved.

Working methods

Once a panel is constituted, its members need to be brought together and encouraged to get to grips with the chosen topic. This has to involve a lot more than just putting them in a room and expecting them to reach considered conclusions by themselves. They will need assistance, both with learning about the topic and with finding ways to work through the issues. PACT already has considerable experience of how to do this well, giving participants impartial support where needed, while ensuring they remain in control of their own conclusions. Or, as John Sultman put it when thanking the staff who supported our Panel,

“they let us wander our own path but somehow kept us from falling off the cliff.”1

Working methods will vary according to the topic and the preferences of each panel, but are likely to involve:

initial induction and scene-setting sessions

a mixture of in-person and online sessions

a mixture of whole-panel (plenary) and smaller break-out groups to encourage all panel members to contribute in ways they find most comfortable

presentations by subject-matter experts

facilitated discussions on possible conclusions

support staff on-hand throughout to take notes and to assist with drafting.

Accountability and follow-up

People’s panels can have an important role in generating recommendations, but the final decision must always rest with elected members. Making decisions, and being accountable for them to the Scottish people, is what MSPs are elected and paid to do, and it would put unreasonable and inappropriate pressure on volunteer panel members if the perception were created that whatever they recommended would automatically be implemented.

Nevertheless, by agreeing to set up a panel in the first place, MSPs are implicitly committing to giving serious consideration to the panel’s conclusions. We recommend providing a considered response, within a reasonable timescale (we suggest normally within 9 months), to all of the panel’s recommendations. It is particularly important that, if any recommendation is rejected, panel members get a proper explanation of why. This is more than just a courtesy to the individuals who contributed to that particular panel exercise; it's also a way to build confidence in the use of panels more generally. We can hardly expect people to respond positively to an invitation letter if the perception has been created from previous such exercises that panel recommendations can be casually disregarded or ignored. John Sultman (a member of the Citizens’ Panel that reported to this Committee) expressed it well when he said: “Not everything that is suggested will go forward – we are all adults and we accept that – but if we never hear feedback, it reinforces the mentality of people asking, “Why should I bother?”1

It should also be seen as good practice to invite panel members to give feedback on their experience of taking part, so that lessons can be learned for future panels.

Finally, we recommend establishing an expectation that any piece of scrutiny work considered important enough to merit input by a people’s panel should be debated in the Chamber. Since we don’t expect panels to be used frequently, we think this is a reasonable expectation, even though there are only a limited number of opportunities for committee-led debates each year. As a courtesy, and in recognition of their contribution, we recommend that panel members should routinely be invited to attend any such debate (and offered reimbursement of any travel and accommodation costs they might incur in doing so).

Response to Citizens’ Panel recommendations

In line with our view that the Parliament should provide a response to panel recommendations, we recognise the same need in this instance – to respond directly to the panel recommendations that we have grouped under this theme.

Recommendation 7

We are supportive of much of this recommendation but not, at this stage at least, every element.

We agree that the Parliament should develop a framework for deliberative democracy that recognises that different solutions are needed for different situations and issues, and ensures diverse participation.

We agree that there should be an expectation of follow-up and a response from the Parliament and (where relevant) the Scottish Government. We agree with the Panel’s suggestion of a 9-month timescale for responding. That would be in line with established practice elsewhere, and seems a reasonable compromise between the need to maintain momentum and a recognition that political decision-making can’t always be done quickly.

We are not currently convinced about allowing for the creation of mixed panels that include MSPs as well as members of the public, but (as noted above) would consider options for panellists to engage with MSPs during their deliberations.

We don’t, at this stage, support the Panel’s call to enshrine a framework for deliberative democracy in legislation. This is partly for practical reasons. Legislating is a complex and resource-intensive exercise. If we were to propose legislation, we would wish to do so on a cross-party basis, through a Committee Bill, and we would be reliant on the support of the Parliament’s Non-Government Bills Unit, which is already under heavy demand. We are doubtful it would be possible to get a Bill developed, introduced and through the 3-stage scrutiny process in what remains of the current session, starting from here.

More fundamentally, however, we are not convinced that legislation is necessary in order to make deliberative democracy a regular part of Parliamentary scrutiny. The Parliament has already demonstrated its ability to organise citizens’ panels without a legislative framework. We can see the argument that a legislative framework provides structure and demonstrates commitment, and putting such a framework in place might be an appropriate long-term goal. But at this early stage, we think it’s more important to retain flexibility and the ability to learn through trial and error; legislation would risk boxing us into a rigid model that we couldn’t adapt as we go along.

The only element of the panel’s preferred model that might require legislation would be a right to time off work for people selected to take part. However, it is doubtful that the Parliament has the power to legislate for such a right, given that the subject-matter of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (which includes protection for workers taking time off work for jury duty) is a “reserved matter” under the Scotland Act 1998.

We recognise that deliberative democracy has an important role to play as part of a wider participation and communication framework to “ensure that the public are consistently informed and consulted on local and national issues”. But we don’t see this as just the Parliament’s role. It is for the Scottish Government to inform people and, where appropriate, consult them on its policy programme; the media also has an important role to play in raising awareness of current issues. For its part, the Parliament already provides information on its website and via social media on ongoing scrutiny work, including consultations run by committees.

As outlined above, our recommendation is for the Parliament and its committees to retain the initiative in identifying topics suitable for consideration by people’s panels, at least during what is meant to be a phase of testing and development. As a result, we are not convinced the case has been made for the Panel’s suggestion of “an annually recurring citizens’ panel with agenda-setting powers”.

Finally, we are not convinced by the idea of forming “local panels with local MSPs with outcomes that are sent up to the national level”. The difficulty here is that the Parliament itself does not operate at local level, but on a Scotland-wide basis. The drivers of scrutiny are the committees, whose members are drawn from all parts of the country and whose remits cover national themes. So even if there was a specific, local issue, within the remit of a committee, that was suitable for consideration by a citizens’ panel, it would not just be local MSPs who would be involved in scrutiny of that issue. Creating an alternative Parliamentary mechanism (that is, sitting outside the existing committee structure) for local consideration of local issues would be a major departure from established ways of working and could be hard to justify. We think that, where there is an appetite to use citizens’ panels to address local issues, this should be taken forward by local authorities (which already have statutory responsibility for community empowerment) – and this is something that the Committee would encourage.

Recommendations 8 and 9

We agree with these two recommendations. We are committed to an iterative approach that is based on evidence of what works best, and that measures the impact of each panel. The Parliament is already doing this, through PACT’s internal and external evaluation process, enhanced by the fellowships being established through SPICe. We also recognise the importance of building cross-party support for deliberative democracy. The consensus that has been achieved within this committee is a good start, and the Committee’s work over the rest of this Parliamentary session will be aimed at extending this to the Parliament as a whole.

Part 3: Committee responses to Citizens' Panel recommendations

The Committee’s inquiry into public participation went beyond the use of deliberative methods and explored various barriers to participation and potential solutions to ensuring that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence and are involved in the work of the Parliament.

The Citizens’ Panel was tasked with providing recommendations on the question:

“How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?”

This part of the report focuses on and responds to Panel recommendations that go beyond deliberative democracy and make suggestions for other ways the Parliament can improve public participation in its work.

Theme 2: Growing community engagement

Under this theme, we have grouped the following three Panel recommendations:

1. Remove barriers to participation so that everyone has an equal opportunity to be involved in the work of the Parliament.

Follow up on previous research by researching different methods of engagement, who they work for, and the resource that is needed to use these methods.

Apply research to use different engagement methods to reach the whole of society, including non-digital and digital approaches.

Be mindful of solutions to reach all parts of society – work together with people to identify and create appropriate engagement methods for start-to-finish inclusion. Innovations like citizens’ panels are good but be careful for how costly they are and how they may not engage people with other responsibilities or concerns such as child caring responsibilities, those on low incomes, those who don’t have flexibility around work.

Have an active approach to seeking out alternative voices and ensuring opportunities to engage are as flexible and as varied as possible: when, how and where people feel comfortable.

Raise awareness that the Scottish Parliament will provide payment which addresses the cost barriers that people face when coming to the Parliament and taking part in engagement activities, such as travel expenses, lost income from time off work, childcare and additional costs related to accessibility requirements.

This could also be expanded so that experts or individuals representing already identified protected groups or minority communities could be paid for a couple of days a month to work with different teams. Paying for engagement isn’t enough to make it effective though – training and education are crucial to make community engage effectively.

Ensure access for people with English as a second language including promoting and improving use of Happy to Translate. Support participation from those with learning disabilities by promoting and increasing the use of Easy Read.

2. Create opportunities for people to use and share their lived experience to engage on issues that they care about.

We heard that people are effective at being experts on things and can upskill and educate themselves very quickly if they need to – COVID-19 proved that. We don't have the bandwidth to feel passionate about everything all the time – but when we do we need to have the channels there to engage.

When identifying witnesses, ensure an even balance between academic and professional experts, and people with lived experience.

Experts by experience panels can be empowered by the process because they are treated as equal and the group can bond and build empathy. Committees could also build communities of practice embedded in communities across Scotland (e.g. farmers group, disability awareness and support groups) to work with members and Parliamentary staff.

5. Ensure that community engagement by MSPs doesn't exclude people that are outwith community groups, including by using evenings, weekends and online services.

Theme 2: progress to date

The Parliament’s Public Engagement Strategy (PES) has a strong emphasis on removing barriers to engagement across a range of areas – participation in the work of committees, communications, events and exhibitions and the visitor experience at Holyrood.

Substantial progress was made in Session 5 and is continuing in Session 6 in expanding the range of engagement methods available to the Parliament – for example, the use of digital tools to allow people to share their views easily with committees; the establishment of experts-by-experience panels to support inquiries; improved processes around child protection and trauma-informed working; and the establishment and expansion of the PACT team so that each committee has a participation specialist working alongside clerks, communications specialists and SPICe researchers.

This aligns with more sophisticated targeting of people via the Parliament’s online and social channels, and the production of “digital explainer” content (podcasts, video, animations etc) and promotional activities. All major events and exhibitions are now aligned with and support the aims of the Public Engagement Strategy.

The pandemic also accelerated the development of the Parliament’s digital capability, with the result that people are now routinely given a choice between engaging in person or remotely. A review of the Parliament’s use of digital engagement tools is currently under way to inform future development and procurement.

Theme 2: Views gathered

The Conveners Group, MSPs and the wider consultation all saw community engagement as a priority area. There was support for flexible approaches to the times and locations of meetings, and the importance of face-to-face options to tackle digital exclusion, but with acknowledgement of the need for a balanced workload (for both members and staff).

Conveners emphasised the need to hear the voices of those who know what’s really happening on the ground. In the open consultation there was support for finding balance between lived experience and expert views, and recognition that existing community structures could be a route to improved and sustained engagement.

In Paris, Citizens’ Assembly members spoke about how being a part of the assembly helped them feel active within city life, helped them to better understand the challenges of public administration, but also helped them to problem-solve issues in their own lives and districts (because they became more aware of schemes and support available to them).

When we took evidence from Panel members, Paul MacDonald explained the thinking behind recommendation 5:

“We found that the systems of engagement had become quite rigid, and we identified multiple groups that are outwith those systems. There are people who are not getting involved. They have an opinion but they are not involved in community groups.”

Maria Schwarz gave a powerful example from her own experience:

“I work full time – I spend a lot of my time at work and I work a lot of overtime. At the weekend, I am tired. I pay the bills and I clean, so I do not have a lot of time left. My biggest barrier is time, so I need things to happen in the evenings or at the weekends, or I need something that I can quickly look up on my phone.”

Theme 2: Committee conclusions

The traditional model of Parliamentary scrutiny involves committees issuing a general call for written submissions, and then inviting a number of expert witnesses to attend their meetings for relatively formal question-and-answer sessions. This model has its strengths, but it prioritises the views of those who already have an understanding of what the Parliament is doing and who have the skills and the resources to engage effectively. Many ordinary people are, in practice, sidelined or ignored, either because they are unaware of the opportunity to engage or because their circumstances make engaging too difficult. As a result, valuable experience and perspectives are missed.

The Parliament has recognised this problem for a long time, and considerable efforts have been made over the years to break down barriers to engagement.

We endorse the work that has already been done and that is currently under way. We acknowledge, in particular, the significance of the Parliament’s Public Engagement Strategy, and the way in which pro-active engagement work has become a routine element in committee inquiries through joint working between clerking teams and PACT.

But it is also clear from what Panel members told us that there are still significant barriers to engagement, and that the Parliament needs to do more, not just to facilitate engagement by those already motivated to share their views or experience, but to reach out to the many others who don’t currently see any reason to engage or who assume they wouldn’t be listened to.

There is a range of further measures that we think could help the Parliament make further progress during the remainder of this session. The Committee would like to see progress in the following areas:

The Conveners Group’s participation, diversity and inclusion strategy (which will be developed taking account of the Panel’s recommendations) could include commitments on how committees could design, plan and deliver public engagement that is relevant to the communities concerned, and commission regular reports on the methods used and an evaluation of their impact.

We welcome the working group that is being established to develop systematic and cost-effective approaches to the use of different languages and formats to increase accessibility in our consultation and participation work, including exploration of accessible digital approaches.

The SPCB should develop a clearer policy on payment for participation, and we recommend that this is supported by a review of how committees communicate with witnesses to ensure that our commitment to meet expenses that might otherwise be a barrier comes across clearly.

The Committee Office already monitors witness diversity and we recommend that this should include tracking the balance between lived experience and expert witnesses, and gathering consistent feedback from witnesses about their experience. This could also form part of the reporting to Conveners Group.

Committees should develop report-writing approaches that make better and more consistent use of evidence gathered outwith formal committee meetings (this will be supported by the planned SPICe academic fellowships reporting by late 2023).

The Public Engagement Group should review the current picture on digital exclusion and how it can be taken into account in the design of Parliamentary services.

Committees should make greater use of “lived experience panels”, building on the examples of the Social Justice and Social Security Committee’s poverty and debt inquiry and the panel planned for the Local Government Committee’s scrutiny of the Housing Bill – together with this Committee’s own experience in the consideration of petitions. This should include consideration of safeguarding and using trauma-informed approaches.

We recognise that cross-party groups already contribute to public participation, by allowing people from diverse backgrounds to engage directly with MSPs in what is expected to be a non-partisan forum. We recommend that the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee considers further whether CPGs have appropriate access to Parliamentary resources, and how their work might be better linked to the scrutiny work of committees. This was a theme that emerged from consultation early in our inquiry, though not one emphasised in Panel recommendations.

Theme 2: Response to Panel recommendations

The Committee is generally supportive of all the recommendations grouped under this theme.

On recommendation 1, we acknowledge the need for the Parliament to do more to reduce barriers to engagement, with the aim of increasing opportunities for people to become involved. We agree that more research is required, and that a range of approaches will be needed (something the Conveners Group might encourage). We also acknowledge the point that high-profile initiatives such as citizens’ panels are costly and can still exclude those with caring responsibilities, low incomes or inflexible work commitments, for whom other approaches will be needed.

We also accept the need for the Parliament to give further consideration to how it can offset the cost barriers that people face when engaging with the Parliament. There is already a witness expenses scheme, and a creche (recently re-opened) that prioritises witnesses with young children, but there may be more that can be done to encourage people to claim expenses where they need to.

We also accept the Panel’s point that paying for engagement is not enough, and that training and education are also needed. We recognise that this is work that is built into the Public Engagement Strategy.

We agree that special provision is needed for those whose first language is not English and those with learning disabilities, including through the Happy to Translate initiative and the publication of information in Easy Read formats. This will be taken forward through the proposed working group.

On recommendation 2, we accept that people need opportunities to share their lived experience, and that ordinary members of the public can educate themselves quickly on issues when given appropriate opportunities. We also recognise the need to strike a balance in committee evidence-taking between academics and other experts and those with relevant lived experience, with the latter given a more prominent role than has often been the case in the past. We recognise that it is for each committee, informed and advised by PACT and other Parliament staff, to decide what balance of evidence is appropriate on a case-by-case basis, with some specialised issues requiring more expert evidence and others where the views of those directly affected are more relevant. We recommend that the balance of witnesses should be tracked over time.

On recommendation 5, we accept the point that the Parliament’s engagement activity can’t just be channelled through established community groups, as not everyone with a valid viewpoint is involved in those. We also acknowledge that for many people with busy working lives, evenings and weekends may be the only times they can find time to engage, and that online tools may be essential to make this practicable. We recommend that this should be considered as part of the Conveners Group’s diversity and inclusion strategy.

Theme 3: Raising awareness of the Scottish Parliament

Under this theme, we have grouped three Panel recommendations:

3. Raise awareness of Parliamentary business in plain and transparent language including visual media

Core principle: Use clear and direct language and visuals to communicate information about Parliament, including legislation.

Undertake research into the general public's level of trust and knowledge about the everyday work of the Scottish Parliament.

How many people are actually satisfied with their dealings with their representatives compared to those who are dissatisfied? What level of understanding do the public have around the difference between Parliament and Government? If people knew that the Parliament was an independent institution here to represent the people of Scotland, pass laws and hold the Government and public bodies to account, they would be more likely to engage.

15. Use media outlets, documentaries and short films to highlight Parliament successes and real-life stories of engagement to improve public perception and trust.

We heard that the Scottish Parliament needs to do more to tell people about its engagement and participation work, as those it reaches are positive about the experience. Then it is a matter of finding the best marketing practices to reach as many people as possible.

Use people who have had positive interaction and experience with Parliament to tell their story through national and local media (TV/radio/newspaper etc.) and community groups. The public sometimes find it easier to digest information by way of another person telling them. Make sure people know about the teams of staff working on engagement as well as MSPs.

16. The Parliament should run a general information campaign explaining the role of the Scottish Parliament – a single brochure or leaflet explaining who your local MSPs are, what a call for views is and the role of the Parliamentary service and its impartiality and separateness from Government.

All age ranges may need more information on what the Parliament does and what it can do for them. We think this is something that could be done quickly.

Theme 3: progress to date

The Parliament’s Public Engagement Group is in the process of commissioning external providers to:

develop a survey toolkit to enable the SP to undertake the collection of evaluation information in a consistent way

undertake in-person surveys of visitors to Holyrood, and

undertake an annual omnibus survey to benchmark and understand attitudes to the Scottish Parliament.

All of these should help to ensure that the Parliament’s activities are evaluated more effectively for their impact.

The Parliament’s website content strategy aims to ensure that content is driven by the needs of the people that use the website. This includes using clearer language and making the work of the Parliament more transparent and understandable to everyone.

Where possible, the Parliament’s communications work highlights the impact the Parliament has on people across Scotland. This involves working with a wide range of national, local and specialist media to encourage coverage of the Parliament’s work and the issues that it is looking at. It also involves using a range of formats and channels, including videos, leaflets, podcasts, case studies, social media stories and animations.

The Main Hall exhibition about the work of the Parliament features video interviews with six people relating their personal experience of campaigning for legislative or policy change, or being positively affected by the work of the Scottish Parliament.